Abstract

Since Zilversmit first proposed postprandial lipemia as the most common risk of cardiovascular disease, chylomicrons (CM) and CM remnants have been thought to be the major lipoproteins which are increased in the postprandial hyperlipidemia. However, it has been shown over the last two decades that the major increase in the postprandial lipoproteins after food intake occurs in the very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) remnants (apoB100 particles), not CM or CM remnants (apoB48 particles). This finding was obtained using the following three analytical methods; isolation of remnant-like lipoprotein particles (RLP) with specific antibodies, separation and detection of lipoprotein subclasses by gel permeation HPLC and determination of apoB48 in fractionated lipoproteins by a specific ELISA. The amount of the apoB48 particles in the postprandial RLP is significantly less than the apoB100 particles, and the particle sizes of apoB48 and apoB100 in RLP are very similar when analyzed by HPLC. Moreover, CM or CM remnants having a large amount of TG were not found in the postprandial RLP. Therefore, the major portion of the TG which is increased in the postprandial state is composed of VLDL remnants, which have been recognized as a significant risk for cardiovascular disease.

Keywords: Postprandial remnant lipoproteins, Chylomicron remnants, Very low density lipoprotein (VLDL) remnants, apoB-48, apoB-100, Remnant-like lipoprotein particles (RLP), RLP-triglyceride (RLP-TG), RLP-cholesterol (RLP-C)

1. Introduction

Plasma triglycerides (TG) are known to be a surrogate for TG-rich lipoproteins (TRL) and are present in chylomicrons (CM), very low density lipoproteins (VLDL) and their remnants. TRL and their remnants are significantly increased in the postprandial plasma and are known to predict the risk of coronary heart disease (CHD) (1, 2), independent of the total cholesterol, LDL or HDL cholesterol level. Recently, non-fasting TG levels have come to be known as a significant risk indicator for CHD events (3–5). Zilversmit (6) first proposed that the postprandial CM is the most common risk factor for atherogenesis in persons who do not have familial hyperlipoproteinemia. The hypothesis of postprandial CM and CM remnants came to be widely accepted as a major cause of common atherogenesis, because it was well established that CM are significantly increased in the intestine after food intake and a large amount of CM flow into the blood stream through the thoracic duct. Therefore, CM and CM remnants have been thought to be the major lipoproteins in the postprandial hyperlipidemia until recently.

Furthermore, Type I and V chylomicronemia, which are associated with severe lipemia, are often confused with common alimentary lipemia. However, severe lipemia is is most commonly associated with a deficiency of lipoprotein lipase (LPL) or apoC II, and significantly elevated CM and CM remnants are detected in the fasting plasma of these cases (7). Type III hyperlipidemia is a kind of postprandial genetic defect which results in significantly elevated apoB48 in beta-VLDL and is associated with the low affinity of apoE2/2 for the receptors which clear remnant lipoproteins (8–11). Alimentary lipemia is often reflected by the increased turbidity of fat emulsions, not CM, in plasma in terms of lipid concentrations. Therefore, the severity of lipemia in the postprandial plasma often weakly correlates with the plasma triglyceride concentration.

Nevertheless, many of the current textbooks on alimentary lipemia or postprandial hyperlipidemia still indicate CM and/or CM remnants as the major lipoproteins which are increased in plasma after food intake. In addition, approximately 80% of the postprandial increase of triglycerides has been considered to be accounted for by the apo B-48 containing lipoproteins until recently (12). This is based on the fact that the CM and/or CM remnants are the major triglyceride-carrier in the postprandial state, with each particle carrying a very large number of triglyceride molecules. Therefore, large quantities of triglycerides are thought to be transported by a very small number of CM or CM remnant particles. As the CM particle size has not been determined, it has remained unclear whether the major TRL in the postprandial plasma was CM-derived or not.

To investigate the characteristics of postprandial lipoproteins, we developed a new immunoseparation method which enables the direct isolation of remnant lipoproteins as remnant-like lipoprotein particles (RLP) from the postprandial plasma and examination of the concentration and particle size of CM and VLDL remnants (13, 14). This method has the capacity to isolate both CM and VLDL remnants from the plasma simultaneously as RLP, which fulfill most of the biochemical characteristics of CM and VLDL remnant lipoproteins.

In this manuscript, we have demonstrated that the major remnant lipoproteins associated with postprandial hyperlipidemia are in fact not CM remnants, but VLDL. To confirm this finding, three new analytical methods developed in Japan during the last two decades were employed; the isolation of remnant-like lipoprotein particles (RLP) using specific antibodies (13, 14), separation and detection of lipoprotein subclasses by a gel permeation high-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) system (15) and determination of apoB48 in fractionated lipoproteins by a highly specific ELISA (16 ).

2. Metabolism of CM, VLDL and their remnants in plasma

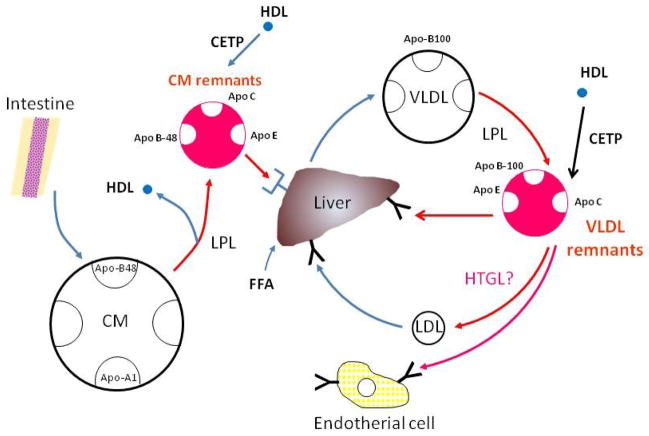

Figure 1 shows the metabolic pathway of CM and VLDL. CM is secreted by the intestine after fat consumption. CM particles contain apo B-48 as a structural protein, which in humans is formed exclusively in the intestine after tissue-specific editing of the apo B-100 mRNA (17, 18). It appears that apo B-48 containing particles are continuously secreted from the enterocyte, and at times of excessive triglyceride availability, lipid droplets fuse with nascent lipoprotein particles, resulting in the secretion of enormous chylomicrons [19, 20]. Once the CM particle reaches the plasma compartment, apoA-I dissociates very rapidly (21) and acquires apo Cs, in particular apo C-II, to enable efficient unloading of its massive triglyceride content after binding to the lipoprotein lipase (LPL) which is bound to the endothelium [22]. High density lipoproteins (HDL) are a major reservoir for the apo Cs and apo E, but in conditions with low HDL concentrations (found most often in hypertriglyceridemic subjects). CM may receive apo Cs and apo E from resident VLDL particles. The half-life of CM triglycerides in healthy subjects is very short, approximately 5 min [23]. The half-life of CM particles has been very difficult to estimate due to the difficulty of obtaining adequate labeling of CM. The CM particle half-life is certainly longer than for CM triglycerides and seems to be quite heterogenous. Certain pools of CM remnants have a very long residence time, at least as long as similar-sized VLDL particles [24, 25].

Figure 1.

After fat intake, the intestine secretes chylomicrons (CM), the triglycerides of which are lipolyzed by lipoprotein lipase (LPL). The LPL reaction constitutes the initial process in theformation of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein (TRL) remnants. The VLDL secretion process is partly regulated by the rate of FFA influx to the liver. VLDL triglycerides are lipolyzed by endothelial-bound lipoprotein lipase and VLDL remnant particles are formed. The final TRL remnant composition is modulated by the cholesterol ester transfer protein (CETP) reaction with HDL, hepatic lipase (HL), and the exchange of soluble apolipoproteins such as C-I, C-II, C-III and E. (A) The great majority of the remnants are removed from plasma by receptor-mediated processes and the principal receptors are the LDL receptor and the LDL-receptor-related protein (LRP). It is probable that the CM remnants use both of these routes, whereas the VLDL remnants are more likely to use only the LDL receptor.

Furthermore, a major proportion of the CM remnants leave the plasma compartment quite rapidly while still quite large, i.e., 75 nm in diameter [24]. There is competition for lipolysis: CM and VLDL mix in the blood and the two TRL species compete for the same lipolytic pathway [25, 26]. It has been shown that endogenous TRL accumulate in human plasma after fat intake and the mechanism behind this phenomenon is explained by the delayed lipolysis of the apo B-100 TRL particles due to competition with CM for the sites of LPL action [26]. Similarly, endogenous TRL accumulate in rat plasma due to competition with a CM-like triglyceride emulsion for the common lipolytic pathway [27]. The increase in the number of TRL apo B-100 particles is actually far greater than that of the apo B-48 containing lipoproteins in the postprandial state [28]. Of note, the accumulation of large TRL apo B-100 particles seems to be a particular sign in hypertriglyceridaemic patients with CAD compared with healthy hypertriglyceridaemic subjects, suggesting a link between the accumulation of large VLDL and the development of atherosclerosis [29].

VLDL particles are secreted continuously from the liver (Figure 1). In contrast to CM and their remnants, they are characterized by their apo B-100 content. The secretion of VLDL is under complex regulation, as the larger and more triglyceride-rich VLDL species are under strict insulin control in a dual sense. First, a number of more or less insulin-sensitive mechanisms regulate the availability of triglycerides for VLDL production. The free fatty acids (FFA) which are generated by lipolysis in adipose tissue through the action of hormone-sensitive lipase provide a major source for hepatic VLDL secretion. Insulin stimulates the endothelial expression of lipoprotein lipase (LPL), the key enzyme in TRL metabolism, in a post-transcriptional manner [30, 31]. Hepatic uptake of poorly lipolyzed VLDL or CM remnant particles may also contribute to the hepatocellular triglyceride availability. Similarly, reduced uptake of FFA in adipose and muscle tissues after LPL-mediated lipolysis of CM and VLDL shunts FFA to the liver [32]. Finally, the liver has the capacity of de novo synthesis of triglycerides and VLDL.

In contrast, the metabolic pathway of VLDL by hepatic triglyceride lipase (HTGL) seems to be still controversial because of the difficulties of measurements. HTGL has been reported to metabolize comparatively small remnant lipoproteins, although to a lesser extent than LPL. However, our recent studies have shown no correlation between HTGL activity and plasma TG, RLP-C, RLP-TG or the small dense LDL-C concentration in humans (33), although we did find a strong inverse correlation between LPL activity and these parameters in both the fasting and postprandial state (Table 1). Previous studies proposed the concept of HTGL role to the remnant metabolism seemed to be mainly based on the animal studies using anti-HTGL antibodies in monkeys and rats and found the accumulation of remnant lipoproteins in plasma after the HTGL specific antibody treatment (34, 35). As it is well known that small dense LDL (sd LDL) is positively correlated with TG and remnant lipoproteins in plasma, these data support the concept that remnant lipoproteins are the precursor of sd LDL and are metabolized in the same pathway by LPL (33). From these data, HTGL does not seem to play a significant role in the metabolic pathway of remnant lipoproteins, in contrast to previous reports (34–38), but instead, plays a definitive role in HDL metabolism in humans.

Table 1.

Single linear regression analysis of plasma lipids, lipoproteins, lipases and ANGPTL3 in 20 volunteers

| TG | RLP-C | RLP-TG | sdLDL-C | HDL-C | LPL | HTGL | ANGPTL3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fasting | ||||||||

| TG | - | |||||||

| RLP-C | 0.72*** | - | ||||||

| RLP-TG | 0.88*** | 0.91*** | - | |||||

| sdLDL-C | 0.56*** | 0.28 | 0.43** | - | ||||

| HDL-C | −0.37** | −0.19 | −0.23 | −0.36** | - | |||

| LPL | −0.43** | −0.27* | −0.25 | −0.22 | 0.33* | - | ||

| HTGL | −0.06 | −0.01 | 0.02 | −0.10 | −0.49*** | 0.08 | - | |

| ANGPTL3 | 0.15 | 0.20 | 0.16 | −0.12 | 0.36** | −0.13 | −0.50*** | - |

| Postprandial | ||||||||

| TG | - | |||||||

| RLP-C | 0.86*** | - | ||||||

| RLP-TG | 0.95*** | 0.86*** | - | |||||

| sdLDL-C | 0.44** | 0.36** | 0.33* | - | ||||

| HDL-C | −0.42** | −0.32** | −0.42** | −0.30* | - | |||

| LPL | −0.38** | −0.40** | −0.42** | −0.21 | 0.35* | - | ||

| HTGL | 0.09 | −0.05 | 0.24 | −0.20 | −0.47*** | −0.19 | - | |

| ANGPTL3 | 0.00 | −0.22 | −0.04 | −0.12 | 0.24 | −0.27* | −0.25 | - |

p<0.05,

p<0.01,

P<0.001

3. Biochemical characteristics of CM and VLDL remnants

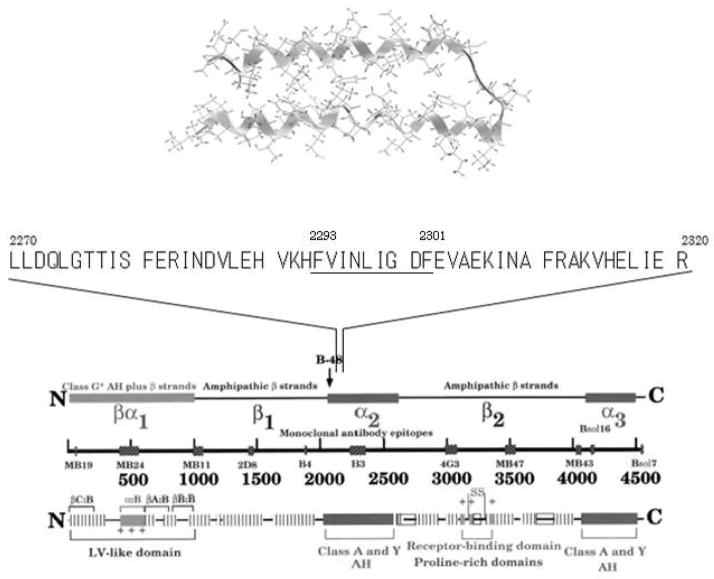

TRL remnants are formed in the circulation when apoB-48 containing CM of intestinal origin or apoB-100 containing VLDL of hepatic origin are converted by lipoprotein lipase (and to a lesser extent by hepatic lipase according to the description commonly given in the literature) into smaller and denser particles (36–38). Compared with their nascent precursors, TRL remnants are depleted of triglyceride, phospholipid, apoCs (and apoA-I and apoA-IV in the case of CM) and are enriched in cholesteryl esters and apoE (40, 41). They can thus be identified, separated, or quantified in plasma on the basis of their density, charge, size, specific lipid components, apolipoprotein composition and apolipoprotein immunospecificity (42). Each of these approaches has provided useful information about the structure and function of remnant lipoproteins, and has helped to establish the role of TRL remnants in the pathogenesis of atherosclerosis. Accurate measurement and characterization of plasma remnant lipoproteins, however, has proven to be difficult for the following reasons: (1) despite their reduced size and triglyceride content, they are difficult to differentiate from their triglyceride-rich precursors; (2) due to their rapid plasma catabolism, they exist in plasma at relatively low concentrations; and (3) since remnants are at different stages of catabolism, they are markedly heterogeneous in size and composition. TRL is known to become progressively smaller, denser and less negatively charged as they are converted into TRL remnants. They gradually lose triglycerides and, in relative terms, become enriched with cholesteryl esters. They also reduce their complement of C apolipoproteins (apoC-I, apoC-II, and apoC-III), which are replaced by apoE. At any given time, there is a continuous spectrum of different-sized remnants in the blood. Some of these particles are of intestinal origin. They contain apoB-48 and are present in greater concentrations after a fat-rich meal. The majority, however in both the fed and fasted state, contain apoB-100 and are derived from the liver. Depending on the extent to which they have been lipolyzed, the different species of TRL contain different proportions of triglyceride and cholesterol and may or may not contain apoCs or apoE. Remnant lipoproteins are thus structurally and compositionally diverse, which has made it necessary to develop a variety of specific biochemical techniques for the detection, quantification and characterization of these lipoproteins. In the light of such difficulties, we endeavored to find a new approach to isolate remnant lipoproteins. An approach which could separate variety of remnant lipoproteins from the normal apoB100 (nascent VLDL and LDL) carrying lipoproteins. A specific anti-apoB-100 antibody which does not recognize α-helix structure of apoB-51 region was developed and used for the isolation of the apoE-rich VLDL remnants (Figure 2) (14).

Figure 2.

The amino acid sequence of the epitope region of the anti-apoB-100 antibody (JI-H) is homologous to an amphipathic helical region of apoE, which suggests that apoE can compete for binding of the antibody with the B-51 amphipathic helical epitope (2270–2321) ( Ref 14). (Nakajima et al. J Clin Ligand Assay 1996;19:177–83.)

4. Daily rhythm of plasma cholesterol, TG and remnant lipoproteins and the changes in the lipoprotein levels after a fat load

The plasma triglyceride concentration fluctuates throughout the day in response to the ingestion of meals. Even if measured after a 10- to 12-hour overnight fast (as is normal clinical practice), triglyceride levels vary considerably more than LDL and HDL cholesterol levels.

As non-fasting TG levels are now known to be a significant risk for CHD events (3–5), the analysis of postprandial lipoproteins, rather than the fasting state, has come to be recognized as more important. We reported that non-fasting TG correlated more strongly with remnant lipoproteins than fasting TG [43]. The correlations between postprandial TG and remnant lipoprotein concentrations were significantly more robust when compared with fasting TG vs remnant lipoprotein concentrations. In particular, the increase of postprandial RLP-TG from fasting RLP-TG contributed to approximately 80% of the increase of postprandial total TG from total fasting TG (Table 2). The greater predictive value of non-fasting TG levels associated with cardiovascular events is directly correlated with the increased levels of remnant lipoproteins in the postprandial state.

Table 2.

Lipids, lipoproteins, RLP-TG/RLP-C ratio and RLP-TG/total TG ratio after oral fat load in 18 male volunteers

| 0 hr

|

2 hr

|

4 hr

|

6 hr

|

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median | 75%tile | Median | 75%tile | Median | 75%tile | Median | 75%tile | |

| TC (mg/dl) | 200 | 217 | 196 | 219 | 193 | 210 | 200 | 212 |

| TG (mg/dl) | 85 | 104 | 140** | 169 | 162** | 206 | 125* | 139 |

| HDL-C(mg/dl) | 62 | 74 | 62 | 73 | 60 | 71 | 61 | 75 |

| RLP-C(mg/dl) | 4.8 | 6.1 | 6.6** | 7.7 | 7.1** | 9.4 | 6.1* | 8 |

| RLP-TG(mg/dl) | 12 | 16 | 63** | 77 | 64** | 101 | 39** | 58 |

| RLP-TG/RLP-C | 2.5 | 2.7 | 8.7** | 10.1 | 9.3** | 13 | 5.8** | 8.7 |

| RLP-TG/TG | 0.13 | 0.15 | 0.45** | 0.47 | 0.42** | 0.56 | 0.34** | 0.41 |

|

| ||||||||

| ◿ TG (mg/dl) | - | - | 56 | 75 | 74 | 102 | 35 | 63 |

| ◿ RLP-TG (mg/dl) | - | - | 51 | 68 | 51 | 85 | 29 | 41 |

| ◿ RLP-TG/◿ TG (ratio) | - | - | 0.82 | 0.94 | 0.8 | 0.91 | 0.82 | 0.94 |

0 hr vs 2 hr, 4 hr, and 6 hr by U-test.

; p<0.05,

; p<0.01

◿ TG; postprandial minus fasting (0 hi) TG, ◿ RLP-TG: postprandial minus fasting (0 hr) RLP-TG

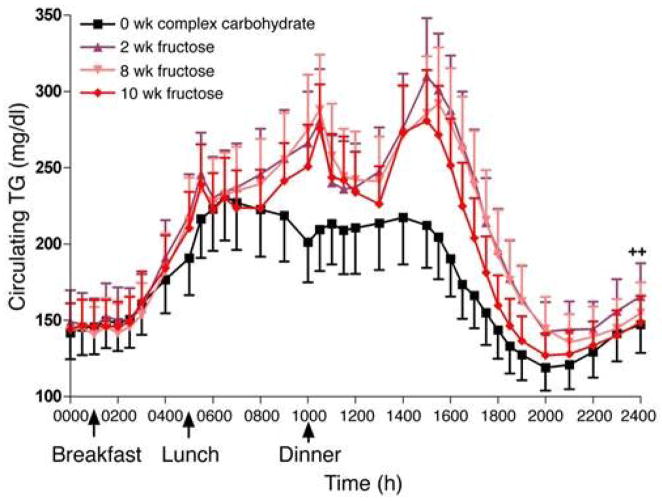

As shown by Stanhope et al. (44) in Figure 3 in their fructose treatment study, plasma TG levels are significantly increased during the day associated with food intake. It was only in the early morning that TG levels in all cases returned to the basal levels. When fructose was administered, a significant increase of TG after food intake compared with the regular meal was observed. Plasma cholesterol levels did not significantly change during the day. Figure 3 shows that blood samples were collected every hour during the 24h day. Between blood samplings, each subject consumed a standardized meal (9 am, 1pm and 6 pm) containing 55% of the energy as carbohydrate, 30% as fat and 15% as protein. The energy content of the meals was based on each subject’s energy requirement as determined by the Mifflin equation (45). Figure 3 shows that the TG levels in generally healthy volunteer plasma were the highest at 2 AM in the very early morning, indicating that postprandial conditions continue even past midnight during in the course of a day, except in the early morning. Remnant lipoprotein levels increased significantly for most of the day except the early morning, a similar profile TG. These increases may depend on the kind of foods. The typical carbohydrate rich Japanese meal did not increase the levels of TG and remnants during a given day compared with a fat-rich meal such as in the typical Western diet (44, 46), as shown by Ai et al. (47) and Sekihara et al. (48).

Figure 3.

Twenty four-hour circulating plasma TG concentrations in subjects before and after 2, 8 and 10 weeks of consuming fructose-sweetened beverages (n = 17). The plasma TG levels were found to be significantly increased during the day associated with food intake in a fructose treatment study. Only in the early morning did the TG levels in all cases returned to the basal levels, and were highest in the middle of the night. Blood samples were collected every hour for 24hs. Between blood samplings, each subject consumed a standardized breakfast (9:00 h), lunch (13:00 h) and dinner (18:00 h) containing 55% of the meal energy as carbohydrate, 30% fat and 15% protein. (Ref. 43) (Stanhope et al. J Clin Invest. 2009; 119:1322–34)

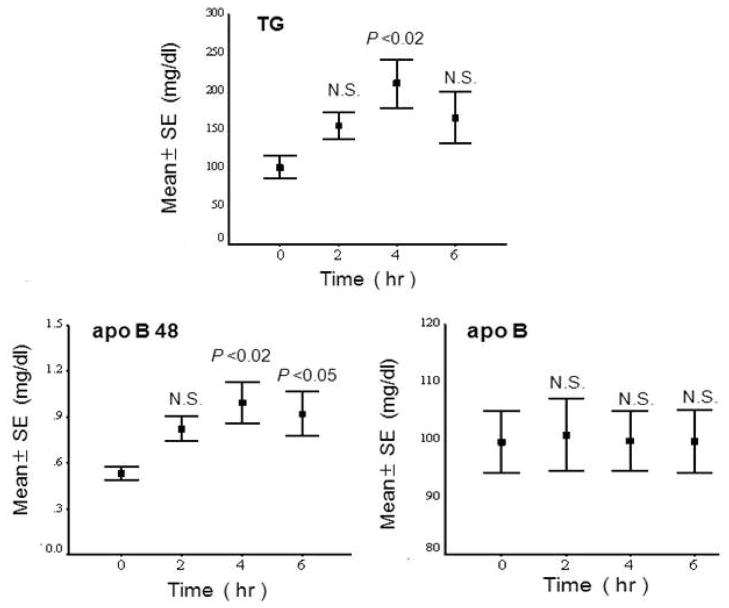

Other postprandial studies have been conducted by oral fat load test. One typical study performed in our laboratory was carried out in 6 male and 6 female (postmenopausal) Japanese volunteers aged 39–60 (mean 52 years) who were generally healthy with no apparent disease (49). Among these 12 volunteers, there were three cases of mild hyperlipidemia (Type IIb). All participants performed an oral fat tolerance test (OFTT) as previously reported (50). Briefly, after a 12 h fast, the subjects ingested 17g fat /m2 body surface area (OFTT cream, Jomo foods, Takasaki. Gunma). The test meal (OFTT cream) had a water content of 56.9%, while lipids accounted for 32.9%, protein for 2.5%, carbohydrates for 7.4% and minerals for 0.3%. The fat was 64.3% saturated, 29.3% monounsaturated and 3.5% polyunsaturated. Blood samples were drawn before and 2, 4 and 6 h after an oral fat load. Plasma apo B-48 significantly increased and correlated with the TG levels in postprandial plasma, however, apoB (more than 98% apoB-100) did not (Figure 4). These results suggest that CM or CM remnants carrying a large amount of TG are the major component of the increase in the postprandial remnant lipoproteins. However, the apoB concentration was far greater than apoB-48 in the plasma, as shown in Figure 4. The ApoB-100 in LDL decreased during a fat load, which resulted in there being no change in apoB despite the increase of apoB100 in the postprandial RLP.

Figure 4.

Postprandial changes in the plasma TG, apoB-48 and apoB concentrations before and after an oral fat load. TG displayed a close correlation with apoB-48, but not with apoB (Ref.48) (Nakano et al., Ann Clin Biochem. 2011; 48: 57–64)

The origin of the cholesterol increase in the postprandial TRL remnants has been investigated by several researchers. Both a single fatty meal and long-term diet have been reported to exhibit a cholesterol accumulation in the TRL fraction less than expected, arguing for a rather limited role of dietary cholesterol in determining the TRL remnant cholesterol level [51, 52]. In fact, the calculated proportion of dietary cholesterol present in the CM fraction was very low, i.e. only one out of 99 cholesterol molecules originated directly from the meal [53]. Obviously, the dietary cholesterol is diluted by the cholesterol undergoing enterohepatic recirculation, but the delayed and incomplete absorption of cholesterol (compared to triglycerides) also argues that cholesterol and triglycerides are not incorporated at similar rates into CM particles. It is likely that the majority of the cholesterol is absorbed at a later stage, further down in the gastrointestinal tract, where the abundance of triglycerides is reduced. Therefore, in the postprandial state the accumulation of cholesterol in CM remnant particles is limited in comparison with the cholesterol-enrichment of VLDL remnants. The major source of the cholesterol in the TRL remnants comes from HDL as a result of CETP activity, which will be described later in this manuscript.

5. Isolation of remnant-like lipoprotein particles (RLP) using specific antibodies and the diagnostic characteristics of the RLP-cholesterol (RLP-C) assay

An assay system based on the recognition of TRL remnants according to their apolipoprotein content and immune-specificity has been developed that provides a quantitative and clinically applicable approach to the measurement of plasma remnant lipoproteins (13, 14). This is the first method to separate remnant lipoproteins from TRL using specific antibodies so as to isolate the remnant fraction under moderate conditions. In this assay, RLP is separated from plasma in unbound fraction by immunoaffinity chromatography with a gel containing an anti–apoA-I antibody and a specific anti-apoB-100 monoclonal antibody (JI-H) (JIMRO II, Otsuka, Tokyo). The former antibody recognizes all HDL and any newly synthesized CM containing apoA-I, whereas the latter antibody recognizes all apoB-100 containing lipoproteins, except for certain particles enriched in apoE. Anti-apoB-100 antibody JI-H recognizes the B51 region of apoB100 and CM has no epitope in this region. Therefore, CM lacking apoA-I, which is defined as the CM remnant (21), is not recognized by the gel and all of the apoB-48 particles in the plasma are isolated in the unbound RLP fraction. The reason the anti–apoB-100 antibody does not recognize the apoE-enriched RLP is not entirely clear, although the amino acid sequence of the epitope region of the apoB-100 antibody is homologous to an amphipathic helical region of apoE, which suggests that apoE should be able to compete for binding of the antibody to its epitope, located between 2270–2320 amino acid from N-terminal on apoB-100 (14) (Figure 2). The amphipathic helical peptide (2293–2301) of the chemically synthesized antibody epitope reacted with the anti apoB-100 antibody (JI-H) and exhibited potent reverse cholesterol transport activity as apoA-I, apo E or HDL. Of further note, this peptide showed an inhibitory effect on CETP activity as well (unpublished data).

HDL, LDL, large CM and the majority of VLDL are thus retained by the gel. The unbound RLP are made up of remnant VLDL containing apoB-100 and CM containing apoB-48, which are routinely measured in terms of cholesterol, although they can also be quantified in terms of triglycerides or specific apolipoproteins (ie, apoB, apoC-III, or apoE) (54, 55). The plasma concentration of RLP-C has been shown to be significantly correlated with the plasma concentration of total TG, VLDL-TG and VLDL-C. It has not been significantly correlated with LDL cholesterol or LDL apoB (56, 57). The physical and chemical properties of lipoproteins which are not recognized by the apoB-100 monoclonal antibody JI-H, subsequently isolated by ultracentrifugation at a density 1.006 g/mL, have been described (58). These lipoproteins contained more molecules of apoE and cholesteryl esters than those that were bound, consistent with them being remnant-like lipoproteins. They had slow pre-b electrophoretic mobility compared with the bound VLDL fraction and ranged in size from 25 to 80 nm. Other lipoproteins, however, may be present when the JI-H monoclonal antibody (together with an anti–apoA-I antibody) is used to isolate RLP by immunoaffinity chromatography from total plasma in the absence of ultracentrifugation (13, 14). HPLC analysis of RLP fractions isolated in this way from normolipidemic and diabetic subjects (14), and fast protein liquid chromatographic analysis of RLP from type III and type IV patients (55), have revealed considerable size heterogeneity in RLP, with particles ranging in size from VLDL to LDL. The relative amount of lipid and apolipoprotein in RLP can also vary considerably from one individual to another. Hypertriglyceridemic patients have more triglyceride and apoC-III, and less apoE, relative to the apoB in RLP, than do normolipidemic subjects (54, 55). Hypertriglyceridemic patients invariably have elevated levels of RLP-C, and the clinical usefulness of this assay depends on the studies which show that RLP-C concentration predicts the presence of coronary or carotid atherosclerosis independently of the plasma triglyceride level (59, 60).

The median concentration of RLP-C is 5.9 mg/dL in 35- to 54-year-old American men and 4.6 mg/dL in similarly-aged women (57). RLP-C is higher in older versus younger subjects,(13, 56), men versus women (56,57), postmenopausal versus premenopausal women(56), the fed versus the fasted state (50, 61), individuals with diabetes (62), patients with familial dysbetalipoproteinemia, (13, 55, 63, 64), hemodialysis patients (48,65) and patients with coronary artery restenosis after angioplasty (66). It has been demonstrated that the RLP-C concentration is significantly higher in patients with CAD than in control subjects (13, 56, 57, 67–69). The potential atherogenicity of RLP-C is supported by the observation that RLP can promote lipid accumulation in mouse peritoneal macrophages (70), stimulate whole-blood platelet aggregation (71, 72) and impair endothelium-dependent vasorelaxation (73). The physiological and pathophysiological aspects of RLP have been investigated extensively by many researchers using isolated RLP fraction in various diseases (74), but relatively little is known about the biochemical composition of RLP or the extent to which this composition varies from one individual to another.

6. Fractionation and analysis of RLP with a gel permeation HPLC system

Gel permeation HPLC is a method for quantifying lipoproteins by particle size (15, 75). Online post column detection of lipid components in lipoproteins particles after separation by size provides quantitative lipoprotein size distribution from whole serum or the RLP fraction. The following combined techniques were used: 1) TSKgel LipopropakXL columns which can separate a wide range of lipoprotein particle sizes from CM to HDL (76), 2) an on-line enzymatic reaction for TC and TG in the separated effluents from the column (77) and 3) 20 component peak analysis using a Gaussian curve fitting technique(78). These techniques can provide CM-cholesterol (CM-C), VLDL-cholesterol (VLDL-C), LDL-C, HDL-C, and total cholesterol (TC) and their triglycerides (CM-TG, VLDL-TG, LDL-TG, HDL-TG and total TG) together with their VLDL, LDL and HDL subclasses. This HPLC method has satisfactory performance on sensitivity, reproducibility and accuracy compared to the reference methods (76). The LipoSearch HPLC analytical service for the TC and TG concentration in the major subclasses of lipoproteins was conducted at Skylight Biotech, Inc (Akita, Japan.: http://www.skylight-biotech.com/eng/service.html)

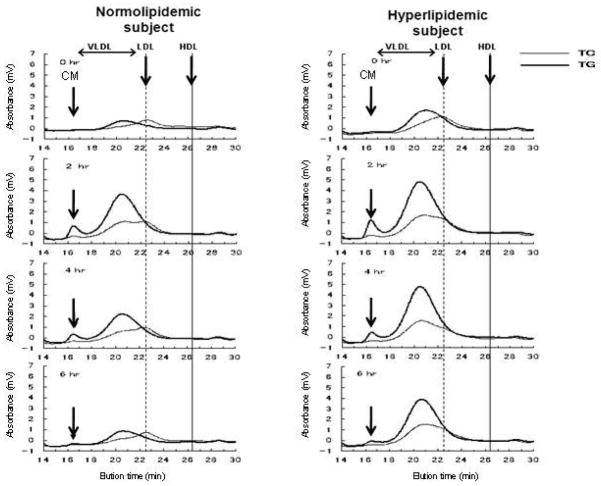

This HPLC system is appropriate for the profiling of TG rich lipoproteins and postprandial samples because of its capacity to separate CM and VLDL. The high sensitivity of this method enables an examination of the particle size distribution in the RLP fractions separated by immunoseparation gels, which are very low in concentration compared with LDL and HDL in plasma. Moreover, the dual detection system of TG and TC provides useful information for determining the heterogeneity of the RLP particles separated by immunoaffinity gels. Using 100μL of supernatant in immnoaffinity gel suspension solution after 2 h incubation (5μL serum or plasma with 300μL immunioaffinity gel solution), the RLP-C and RLP-TG profiles can be directly observed with an on-line dual detection method using gel permeation HPLC (77). Figure 5 shows a typical profile of the postprandial RLP monitored by TC and TG reagents in normolipidemic and hyperlipidemic cases after a fat load (49). The particle sizes are shown in a range of VLDL to LDL before (0 h) and after (2, 4, 6h) an oral fat load. A small peak at the void retention time was detected at 2h and 4h, in each case as large TG-rich lipoproteins. The clearance of the VLDL fraction was significantly delayed in a hyperlipidemic subject compared to a normolipidemic subject.

Figure 5.

Typical profiles of RLP-TG and RLP-C in the postprandial plasma of a normolipidemic (TG<150 mg/dL) and a hyperlipidemic (TG>150 mg) subject after oral fat load. The RLP fraction was monitored by TC and TG with an HPLC system. After 5μL serum was incubated with 50μL of immnoaffinity gel (300 μL of gel suspension solution) for 2h as the RLP-C assay, 100μL of the supernatant of the unbound fraction were applied to the HPLC system. RLP was always detected with a large VLDL particle size (thin line; RLP-C, thick line; RLP-TG) and a small peak in the void fraction comprised of the CM size. The clearance of RLP-C and RLP-TG was delayed in the hyperlipidemic case, while clearance in the normolipidemic case returned to the basal level in 6h ( Ref. 97) (Nakano et al., Clin Chim Acta 2011; 412: 71–78)

Another approach is to isolate a large amount of RLP from the plasma for further HPLC fractionation. For example, 0.2ml aliquots of plasma were applied to columns containing 2ml of immunoaffinity mixed gel. The plasma samples were incubated with the immunoaffinity mixed gel at room temperature for 30min. Lipoproteins unbound from the gel (containing primarily CM and VLDL remnants) were eluted with 3.5 ml of 10mM phosphate buffered saline (pH 7.2). The unbound fraction was concentrated with an Amicon Ultra filter (Millipore, USA) for HPLC fractionation and analysis. The concentrated RLP fraction was fractionated by HPLC and 0.35 ml of aliquot in each tube was collected for the determination of TC, TG, apoB-48 and apoB-100 (49).

7. Determination of serum apoB-48 with ELISA

The characteristics and development of the apo B-48 ELISA assay using monoclonal antibodies have been reported by the two groups in Japan[16, 79, 80]. The ELISA for apo B-48 for this study was obtained from Shibayagi (Shibukawa, Gunma) (16). The assay uses a monoclonal antibody raised against a C terminal decapeptide of the apo B-48 protein and was calibrated using recombinant apo B-48 antigen (81). The monoclonal antibody has no cross-reactivity with apo B-100, as verified by ELISA and Western blotting, with more than 90% recovery of apo B-48, and the assay has within- and between run coefficients of variation of 4.8% and 5.4%, respectively. The assay was tested in healthy fasting Japanese volunteers with mean reported values of 0.460 ± 0.15 mg/dL (range 0.27–0.81 mg/dL). In healthy volunteers tested at 0, 2, 4 and 6 h after a 40g fat load, serum apo B-48 and TG increased approximately 2-fold, with a similar peak time of 3 to 4 h [16, 80]. The apoB48 ELISA determined the apoB48 protein in the large TG-rich lipoprotein particles in severe lipemic plasma by pre-treatment with detergent (0.1% Triton X-100). The assay had a sensitivity of 0.25 ng/mL; and a linear dynamic range at 2.5 to 40 ng/mL. Interference with the assay values was noted in the hemoglobin values of at least 106 mg/dL and bilirubin values of at least 10 mg/dL. To further validate this assay, whole plasma and the TRL fraction (after subjecting plasma to ultracentrifugation at its own density of 1.006 g/mL for 18 hours) was studied (82). TRL samples were subjected to gel electrophoresis for the separation of apo B-100 and apo B-48, followed by gel scanning, showed that the mean TRL apo B-48 value was 1.01 mg/dL (SD, 0.43 mg/dL) using ELISA and 0.50 mg/dL (SD, 0.20 mg/dL) using gel scanning. The correlation coefficient or r value between the 2 methods was 0.82 (P <001) (82), highly correlated. Therefore, although the 2 methods correlate well, and the gel method yielded TRL apo B-48 concentrations that were approximately 50% lower than the ELISA values, indicating that a correction factor of 2.02 would need to be applied to prior kinetic studies (12) in which the TRL apo B-48 levels had been assessed by gel scanning. Furthermore, Nakano et al. (83) determined the concentration of apoB-48 and apoB-100 carrying lipoprotein particles extracted from human aortic atherosclerotic plaques in sudden death cases. The plasma apo-B48 level was shown to be significantly elevated in type III cases, as previously reported (55, 80). Therefore, this method was applicable to the determination of the apoB48 concentration in the fractionated RLP using an HPLC system.

8. Postprandial remnant metabolism in CETP deficiency

Plasma cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) mediates the CE/TG exchange from HDL to TG-rich lipoproteins which forms remnant lipoproteins (Figure 1). Fielding et al. (84) reported that CETP activity was significantly increased in the postprandial state almost in parallel with the increase of plasma TG. The RLP-C and RLP-TG levels were increased along with elevated CETP activity in patients with nephrotic range proteinuria (85). Therefore, CETP activity and remnant formation are evidently closely associated.

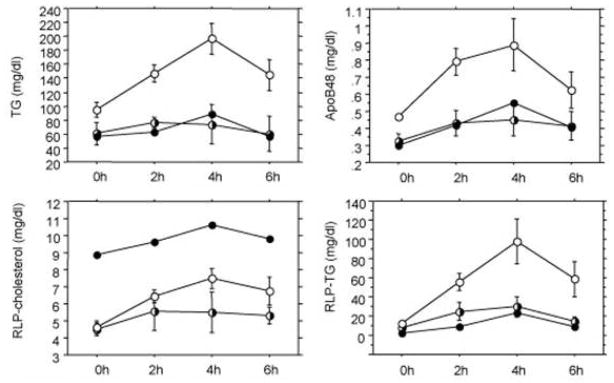

CETP deficiency results in a low LDL/high HDL phenotype including apoE-rich large HDL. Large HDL may provide cholesteryl ester and apoE to CM/VLDL during lipolysis in the postprandial state, accelerating remnant lipoprotein formation and uptake in the liver. To investigate the role of CETP in postprandial lipoprotein metabolism, the lipid levels of plasma RLP were determined in one homozygous and three heterozygous CETP deficiency cases and controls with an apoE3/3 phenotype by Inazu et al. (86). After oral fat-load, the area under the curve (AUC) of the TG, RLP-TG and apoB48 levels was remarkably decreased in heterozygous CETP deficiency as compared to the controls (Figure 6). Similarly, the homozygote had a significantly low AUC for the TG, RLP-TG and apoB-48 levels.

Figure 6.

The plasma TG, RLP-C, RLP-TG and ApoB-48 concentrations after a fat-load. The bars indicate the S.E.M and each time point is shown for the homo-, heterozygotes and controls. The open circles indicate controls; half-shaded circles indicate heterozygotes; closed circles indicate data from a CETP-deficient homozygote as a reference. CETP deficiency results in a significantly reduced TRL remnant formation in the postprandial state. (Ref. 85)(Inazu et al. Atherosclersois 2008; 196: 953-57).

HPLC analysis in the homozygote showed that the increased RLP-C was not due to the conventional VLDL size RLP, but to those of large HDL size. In heterozygotes, a bimodal distribution of the RLP-C level was found for the conventional VLDL and large HDL sizes. Subjects with CETP deficiency appeared to have low levels of TG response and diminished remnant lipoprotein formation after a fat-load.

Ai et al. (87) also found a unique profile of serum postprandial RLP-C and RLP-TG during a fat load in a male CETP deficiency patient, aged 40, whose serum HDL-C, apo-AI and TG levels were abnormally elevated. From the genetic analysis, this case was a compound heterozygote with s known mutation of Intron 14 G(+1) > A and R268X. The former mutation is common, but the latter had not been reported previously in the Japanese population. This is the reason the CETP level was less than the detectable limit. Because of this CETP deficiency, HDL is unable to exchange its cholesteryl ester with the TG of other lipoprotein particles, including RLP (86–88). In this case, it is not clear whether the CETP deficiency was the cause of the profile of the postprandial RLP-C and RLP-TG. A similar CETP deficient case with abnormally elevated TG was previously reported by Ritsch et al. (89) and precise genetic analysis of CETP was performed to find the cause of the dissociation between the cholesteryl ester and TG transportation in plasma. However, they could not find any specific cause in that case, and she was completely CETP deficient as well as being an apo-E2 carrier. The serum levels of RLP-C and RLP-TG as well as total TG usually increase and decrease in parallel after an oral fat load in normal individuals. Also, both RLP-C and RLP-TG in CETP deficient cases are usually reduced, as reported by Inazu et al. (86). However, in this case subject, the serum RLP-C level was highly elevated in the fasting state and did not increase after a fat load, but rather decreased, while the RLP-TG and total TG levels significantly increased after a fat load, with a delayed peak time compared with normal control subjects. This phenomenon indicated that CETP and HDL played an important role in the formation of RLP-C ( but not RLP-TG), as has been reported for postprandial lipid metabolism in homo- and heterozygous CETP deficiency cases (86) and the in vitro formation of RLP with CETP deficiency by Okamoto et al. (88). However, interestingly, the RLP-TG and total TG levels in this case subject increased significantly at 240 mins after a fat load, like those in common hyperlipidemic cases. The trend of the case subject was similar to that of individuals treated with estrogen, whose serum RLP-C level is reduced, but RLP-TG level increases, after the treatment (90, 91). This means that the major metabolic pathways of RLP-C and RLP-TG in the postprandial state are controlled independently, although the RLP particle itself is of the same structure as other lipoproteins i.e. comprised of TC, TG, phospholipids and apolipoproteins, and of isolated by the same immunoseparation method. In the case subject, found an extremely elevated plasma ANGPTL3 level, which was discovered as an inhibitory modulator of LPL and HTGL in mice (92). However, it was recently reported that ANGPTL3 associates more strongly with EL or HTGL, which controls HDL-C metabolism, but not with TG or remnants in humans (33, 93). As the case subject Ai et al. reported (87) showed nearly normal LPL and HTGL activity in post-heparin plasma, ANGPTL3 was shown not to affect RLP-TG levels associated with LPL and HTGL activities (33). However, the lack of CETP together with enhanced EL or HTGL inhibition by elevated ANGPTL3 may have affected a significantly increase of the HDL-C level, especially apo-E-rich HDL in this case.

Another interesting dissociation between RLP-C and RLP-TG in the postprandial plasma was observed in one of the heterozygous CETP-deficient subjects (CC-2) after a fat load (87). The serum RLP-C and RLP-TG levels reportedly increase and decrease in parallel after an oral fat load in most of the study cases (46, 95, 96). However, one heterozygous CETP-deficient subject with increased RLP-C and RLP-TG (VLDL size remnants) after a fat load exhibited RLP-TG which started to separately decrease at 240 mins and RLP-C in 360 mins. This dissociation may be associated with the magnitude of CETP deficiency, in which case CC-2 still enhances the formation of VLDL size RLP-C and RLP-TG, but is apparently insufficient to complete the normal pathway between CETP and LPL (97). These cases may be associated with some genetic disorder of either CETP or its activity, resulting in the dissociated clearance of RLP-C and RLP-TG.

As LPL metabolizes TRL and CETP enhances the formation of both CM and VLDL remnants, the balance of LPL and CETP activity may determine the major components of the postprandial remnant lipoproteins. Further, CETP deficiency itself may not be atherogenic, whereas together with elevated RLP may it be atherogenic and pose a risk for CHD. These cases may help to clarify the controversy whether CETP deficiency is atherogenic or not.

9. RLP-TG as a marker for the analysis of postprandial remnant lipoproteins

RLP-C has been considered as a risk factor for cardiovascular disease for the last two decades. Most of the studies in the literature have reported the RLP-C concentration in the fasting state (74). The lack of sensitivity of the TG measurement in the RLP fraction made us delay an intended investigation of RLP-TG. Recently, we have established a satisfactory assay of RLP-TG which enabled us to determine the concentration of RLP-TG reference range in the Japanese population (98).

The simultaneous measurement of TG and cholesterol in RLP resulted in a RLP-TG/RLP-C ratio which reflects the RLP particle size, as shown by the HPLC profile reported by Okazaki et al. (99). The RLP-TG/RLP-C ratios showed the the variety of the RLP particle sizes in various lipid disorders and under different physiological conditions; For example, Type III cases exhibited a significantly lower RLP-TG/RLP-C ratio which indicated the presence of a higher cholesterol content in RLP (mainly IDL), while the RLP-TG/RLP-C ratio was increased significantly in the postprandial state, indicating a significantly increased TG content in RLP (mainly large VLDL), as shown in Figure 5. Therefore, the RLP-TG/RLP-C ratio predicted the particle size of RLP in a manner comparable with the HPLC profile.

Although RLP-C also increased after an oral fat load, the changes in the RLP-C/total TG ratio in the postprandial state were not significantly different from the ratio in the fasting state. This is because the percentage of RLP-C in the total TG (RLP-C/total TG ratio) was approximately only 5% in the fasting and 4% in the postprandial state. However, a RLP-C/total TG ratio above 10% in the fasting state is now commonly used for the detection of Type III hyperlipidemia (63, 64, 100). In contrast, the RLP-TG/total TG ratio was approximately 10–15 % in the fasting state, and the ratio increased significantly to more than 40% in the postprandial state. Therefore, we investigated the postprandial changes in the RLP-TG/total TG ratio after an oral fat load (49, 98). The postprandial RLP-TG/total TG ratio increased more than 3 fold in 2 h and RLP-TG made up almost half of the total TG (Table 2). In terms of total TG, we have also studied the TRL-TG ratio with RLP-TG, which is the major fraction of the total TG as VLDL (d<1.006). The RLP-TG/TRL-TG ratio changed significantly more than the RLP-TG/total TG ratio.

The particle size predicted by the RLP-TG/RLP-C ratio reflects a significant time-dependent increase of TG in RLP particles in the postprandial state. RLP-TG increased 5.3 fold in 4h, while RLP-C increased 1.5 fold, as shown in Table 2. Therefore, we have found that RLP-TG is a better maker than RLP-C for a direct comparison with total TG in the postprandial state. The RLP-TG/total TG ratio may reflect LPL activity, because LPL activity was shown to be inversely correlated with the concentration of RLP and TG (33). If a subject has a fasting RLP-TG/total TG ratio above 0.13 (95% percentile in TG less than 150 mg/dL ) (98) or an RLP-TG above 20 mg/dL in the fasting state, it may be a subject who is still in the postprandial state and this reflects the delayed remnant lipoprotein metabolism because of disturbed LPL activities. A higher RLP-TG/total TG ratio may be associated with an increased risk for CHD (29, 59, 60, 101).

10. Characteristics of the RLP isolated from postprandial plasma

As reported by Karpe et al. (29), CM is more susceptible to lipoprotein lipase (LPL) than is VLDL. Therefore, the greater susceptibility to LPL of CM rather than VLDL may more readily result in the formation and accumulation of VLDL remnants than CM remnants in the postprandial state. Therefore, the accumulation of large RLP particles in 4h after an oral fat load may be due to the delayed metabolism of VLDL by LPL. Schneeman et al. (102) also reported the postprandial responses (after fat load) of apoB-48 and apoB-100 were highly correlated with those of TRL triglycerides. Although the increase in apoB-48 represented a 3.5-fold difference in concentration as compared with a 1.6-fold increase in apoB-100, apoB-100 accounted for approximately 80% of the increase in lipoprotein particles in TRL. The increase in the number of apoB-100 particles in RLP (VLDL remnants) is actually far greater than that of the apoB-48 particles (CM remnants) in the postprandial state (102,103).

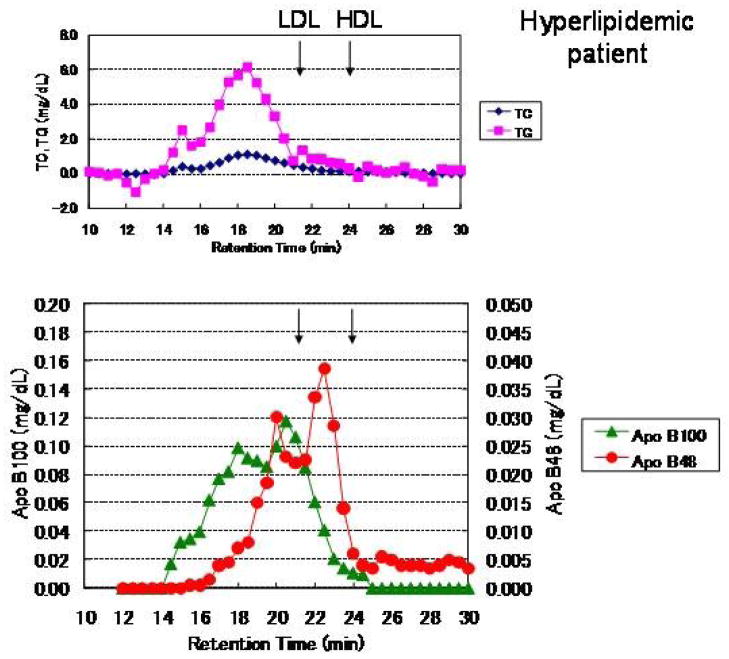

The RLP isolated from plasma in healthy subjects after an oral fat load using an immunoaffinity mixed gel was significantly increased (49). Figure 5 shows the typical profile of RLP particle size in the range of VLDL to LDL at 0, 2, 4 and 6h after an oral fat load, when monitored by TC and TG with HPLC in a normolipidemic and hyperlipidemic subject, respectively. CM or CM remnants (apoB48) could be detected at void volume (a retention time of 15 min). Figure 7 shows a typical RLP profile isolated from the plasma of a Type IIb hyperlipidemic subject 4 h after an oral fat load. RLP was fractionated by HPLC equipped with gel permeation columns (TSK Lipopropak XL, Toso, Tokyo) (77) and 0.35 ml of aliquot each was collected for the determination of TC, TG, apoB-48 and apoB-100 (Figure 7). The peak of the TC and TG retention time in RLP fractionated by HPLC was observed almost at the same particle size as the apoB-100 peak, but was not the same as the apoB48 peak, as shown in Figure 7. Furthermore, the apoB-48 particle size was similar or smaller than that of apoB-100. These results clearly demonstrate that postprandial RLP do not have any apoB-48 particles carrying a large amount of TG in the void fraction, which may thus be categorized as nascent CM (76, 77). The scale (perpendicular axis) of the apoB-100 (left) and apoB-48 (right) concentration in Figure 7 is 4 fold different, but there are similar areas under the curve. Therefore, the significantly higher concentrations of apoB-100 than apoB-48 in postprandial RLP of similar particle size were found in both normolipidemic and hyperlipidemic cases (49). These results show that approximately 80% of the RLP in the postprandial state is composed of large VLDL with apoB100. The increase of small VLDL such as intermediate density lipoproteins (IDL, Sf 12–20) in the postprandial state has been reported to not be increased in the postprandial state (12, 104), even though IDL has often been defined as a typical remnant lipoprotein.

Figure 7.

A typical profile of postprandial RLP in a hyperlipidemic subject. RLP was isolated and fractionated by HPLC from the postprandial plasma of a hyperlipidemic subject (fasting level: TC; 238, TG; 196, HDL-C; 53, LDL-C; 111, RLP-C; 7.0, RLP-TG; 69, apoB; 92, apoB48; 0.86 mg/dL) (in) 4 h after an oral fat load. The RLP fractionated by HPLC was monitored for total cholesterol (TC) and triglycerides (TG) (top) as well as for apoB-48 and apoB-100 (bottom). The scale (perpendicular axis) of the apoB-100 (left) concentration is 4 fold higher than that of apoB-48 (right), but displays a similar area under the curve. The major particles in RLP were of VLDL size as monitored by apoB-100, and the comparatively smaller size of CM as monitored by apoB-48 ( Ref. 48) (Nakano et al., Ann Clin Biochem. 2011; 48: 57–64.)

11. Postprandial remnant hyperlipoproteinemia in sudden cardiac death (SCD)

Clinical studies have shown that elevated plasma TG levels greatly increase the risk of sudden cardiac death. Results from the Paris Prospective Study (105) and The Apolipoprotein Related Mortality Risk Study (AMORIS) in Sweden (106) as well as the coronary heart disease mortality in a 24-year follow-up study in China (107) demonstrated that increased TG was a strong risk factor for fatal myocardial infarction. However, plasma TG levels vary often over even a short period of time. Therefore, it has been difficult to identify the relationship between clinical events and elevated TG in the long term prospective studies until recently (3–5).

If the lipid and lipoprotein levels in postmortem plasma correctly reflect the antemortem levels, these data would provide the same values with the results obtained from the prospective studies, which are difficult to obtain in that they require long-term observation to evaluate. The plasma levels of lipids and lipoproteins in sudden death cases may reflect the condition of the subject at the moment of fatal clinical events followed by certain inevitable postmortem alterations, but nevertheless still usefully reflect the physiological conditions when the fatal events had occurred. Therefore, we analyzed postmortem plasma under well-controlled conditions to clarify the cause or risk of sudden cardiac death. Plasma RLP-C and RLP-TG levels vary greatly within a short time do the TG levels, unlike other stable lipoprotein markers such as HDL-C and LDL-C. Hence, the cross-sectional study of RLPs at the moment of sudden death may be superior to a prospective study of RLP in determining the potential risk for CHD (108). During the investigations of sudden death cases, we found that the postmortem alterations of lipoproteins in plasma were unexpectedly slight (109) compared with the proteins or other bio-markers. Moreover, these plasma lipoprotein levels were very similar to those determined in living patients, based on the clinical studies in our laboratory.

More than two thirds of the SCD cases observed in our studies, including Pokkuri death syndrome (PDS; sudden cardiac death cases without coronary atherosclerosis), showed stomach full, indicating a strong association with postprandial remnant hyperlipoproteinemia. Significant remnant hyperlipoproteinemia was observed in the plasma of SCD cases compared with the control death cases (69, 103, 110–114). These data suggest that the increased RLP in SCD cases may be mainly composed of CM remnants. However, unexpectedly, we found no significant differences in the apoB-48 levels in plasma or in terms of RLP apoB48, but found a significant increase of RLP aoB100 levels in SCD compared to the control cases (103). The RLP apoB100 levels were significantly increased in the SCD cases in the postprandial state (when RLP-C and RLP-TG were significantly increased), however, neither the plasma apoB48 nor RLP apoB48 level was significantly increased. These results strongly suggested that the major subset of RLP associated with fatal clinical events with the stomach full was the apoB-100 carrying particles, not the apoB-48 particles.

The absolute amount of apoB-100 in RLP is much greater (approximately 7 fold) than that of apoB-48 in RLP. Also the particle size of apoB-48 and apoB-100 was very similar, as shown in Figure 7 (114). Furthermore, we often found SCD cases who had consumed alcohol on a full stomach. It is known that alcohol increases fatty acids in the liver and enhances VLDL production while inhibiting LPL activity (115). Alcohol intake with a fatty meal is well known to greatly increase TG in the postprandial state. The intake of alcohol together with a fatty meal may thus enhance the production of apoB100 carrying VLDL in the liver and increase VLDL remnants by inhibiting LPL activity, resulting in an increase in the potential risk of coronary artery in SCD cases (116).

12. Conclusion

Three new analytical methods were used to investigate the characteristics of postprandial lipoprotein metabolism. These were a method of isolating the remnant lipoproteins as RLP using specific antibodies, gel permeation HPLC and apoB48 ELISA. The major portion of the TG which increased in the postprandial state was shown to be TRL remnant lipoproteins. Although Zilversmit proposed CM or CM remnants as the major lipoproteins which increased in the postprandial lipemia, we have shown that the major portion of the postprandial lipoproteins which increased after food intake was comprised of VLDL remnants. The amount of apoB48 particles was shown to be much lower than apoB100 particles in the postprandial RLP, and the particle sizes of apoB48 in RLP were similar with those of apoB100 or smaller when analyzed by gel permeation HPLC system. We did not find CM or CM remnants having a large amount of TG in postprandial RLP. Therefore, the major part of postprandial TRL remnants is composed of VLDL remnants (approximately 80% or more), not CM remnants. It was also found that TG versus RLP-TG concentrations in the postprandial state correlated significantly higher than in the fasting state. Furthermore, it was demonstrated that approximately 80 % of the increased TG in the postprandial state consisted of the TG in remnant lipoproteins. Taken together, we propose the following equation for the estimated concentration of the increased remnant lipoproteins in the postprandial plasma; (Postprandial TG - Fasting TG) x 0.8 = RLP-TG, to reflect the increase in the postprandial plasma as being mainly composed of VLDL remnants.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Dr. Richard Havel, University of California San Francisco, and Dr. Ernst Schaefer, Tufts University Boston for their long term collaboration on remnant lipoprotein research. Also we greatly thank Drs. Sanae Takeichi, Takeichi Medical Research Laboratory, and Masaki Q Fujita, Keio University, for their research collaboration on sudden cardiac death and remnant lipoproteins.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Havel RJ. Postprandial hyperlipidemia and remnant lipoproteins. Curr Opin Lipidol. 1994;5:102–9. doi: 10.1097/00041433-199404000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Havel RJ. Remnant lipoproteins as therapeutic targets. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2000;11:615–20. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200012000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Iso H, Naito Y, Sato S, et al. Serum triglycerides and risk of coronary heart disease among Japanese men and women. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;153:490–9. doi: 10.1093/aje/153.5.490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nordestgaard BG, Benn M, Schnohr P, Tybjaerg-Hansen A. Nonfasting triglycerides and risk of myocardial infarction, ischemic heart disease, and death in men and women. JAMA. 2007;298:299–308. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bansal S, Buring J, Rifai N, Mora S, Sacks FM, Rider PM. Fasting compared with nonfasting triglycerides and risk of cardiovascular events in women. JAMA. 2007;298:309–16. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.3.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Zilversmit DB. Atherogenesis: a postprandial phenomenon. Circulation. 1979;60:473–85. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.60.3.473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fojo SS, Brewer HB. Hypertriglyceridaemia due to genetic defects in lipoprotein lipase and apolipoprotein C-II. J Intern Med. 1992;23:669–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1992.tb01256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Demacker PN, Bredie SJ, Vogelaar JM, et al. Beta-VLDL accumulation in familial dysbetalipoproteinemia is associated with increased exchange or diffusion of chylomicron lipids to apo B-100 containing triglyceride-rich lipoproteins. Atherosclerosis. 1998;138:301–12. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00035-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meng MS, Gregg RE, Schaefer EJ, Hoeg JM, Brewer HB., Jr Presence of two forms of apolipoprotein B in patients with dyslipoproteinemia. J Lipid Res. 1983;24:803–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kane JP, Chen GC, Hamilton RL, Hardman DA, Malloy MJ, Havel RJ. Remnants of lipoproteins of intestinal and hepatic origin in familial dysbetalipoproteinemia. Arteriosclerosis. 1983;3:47–56. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.3.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haffner SM, Kushwaha RS, Hazzard WR. Metabolism of chylomicrons in subjects with dysbetalipoproteinaemia (type III hyperlipoproteinaemia) Eur J Clin Invest. 1989;19:486–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1989.tb00264.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cohn JS, Johnson EJ, Millar JS, et al. Contribution of apoB-48 and apoB-100 triglyceride-rich lipoproteins (TRL) to postprandial increases in the plasma concentration of TRL triglycerides and retinyl esters. J Lipid Res. 1993;34:2033–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nakajima K, Saito T, Tamura A, et al. Cholesterol in remnant-like lipoproteins in human serum using monoclonal anti apo B-100 and anti apo A-I immunoaffinity mixed gel. Clin Chim Acta. 1993;223:53–71. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(93)90062-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakajima K, Okazaki M, Tanaka A, et al. Separation and determination of remnant-like particles in serum from diabetes patients using monoclonal antibodies to apo B-100 and apo A-I. J Clin Ligand Assay. 1996;19:177–83. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Okazaki M, Usui S, Hosaki S. Analysis of plasma lipoproteins by gel permeation chromatography. In: Rifai N, Warnick GR, Dominiczak MH, editors. Handbook of Lipoprotein Testing. Washington DC: AACC Press; 2000. pp. 647–69. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kinoshita M, Kojima M, Matsushima T, Teramoto T. Determination of apolipoprotein B-48 in serum by a sandwich ELISA. Clin Chim Acta. 2005;351:115–20. doi: 10.1016/j.cccn.2004.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Powell LM, Wallis SC, Pease RJ, Edwards YH, Knott TJ, Scott J. A novel form of specific RNA processing produces apolipoprotein B-48 in intestine. Cell. 1987;50:831–40. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(87)90510-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen S-H, Habib G, Yang C-H, et al. Apolipoprotein B-48 is the product of messenger RNA with an organ-specific inframe stop codon. Science. 1987;238:363–6. doi: 10.1126/science.3659919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hayashi H, Fujimoto K, Cardelli JA, Nutting DF, Bergstedt S, Tso P. Fat feeding increases size, but not number of, chylomicrons produced by small intestine. Am J Physiol. 1990;259:709–19. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.1990.259.5.G709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Martins IJ, Sainsbury AJ, Mamo JCL, Redgrave TG. Lipid and apolipoprotein B48 transport in mesenteric lymph and the effect of hyperphagia on the clearance of chylomicron-like emulsions in insulin-deficient rats. Diabetologia. 1994;37:238–46. doi: 10.1007/BF00398049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vinge JL, Havel RJ. Metabolism of apolipoprotein A-I of chylomicrons in rats and humans. Can J Biochem. 1981;59:613–9. doi: 10.1139/o81-085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Patsch J. Postprandial lipaemia. BaillieÁre’s Clin Endocrinol Metabolism. 1987;1:551–80. doi: 10.1016/s0950-351x(87)80023-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grundy SM, Mok MYI. Chylomicron clearance in normal and hyperlipoproteinemic subjects. Metabolism. 1976;25:1225–39. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(76)80006-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Karpe F, Olivecrona T, Hamsten A, Hultin M. Chylomicron/chylomicron remnant turnover in humans: evidence for margination of chylomicrons and poor conversion of larger to smaller chylomicron remnants. J Lipid Res. 1997;38:949–61. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Brunzell JD, Hazzard WR, Porte D, Bierman EL. Evidence for a common, saturable, triglyceride removal mechanism for chylomicrons and very low density lipoproteins in man. J Clin Invest. 1973;52:1578–85. doi: 10.1172/JCI107334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.BjoÈrkegren J, Packard CJ, Hamsten A, et al. Accumulation of large very low density lipoprotein in plasma during intravenous infusion of a chylomicron-like triglyceride emulsion reflects competition for a common lipolytic pathway. J Lipid Res. 1996;37:76–86. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karpe F, Hultin M. Endogenous triglyceride-rich lipoproteins accumulate in rat plasma when competing with a chylomicron-like triglyceride emulsion for a common lipolytic pathway. J Lipid Res. 1995;36:1557–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Karpe F, HelleÂnius M-L, Hamsten A. Differences in postprandial concentrations of very low density lipoprotein and chylomicron remnants between normotriglyceridemic and hypertriglyceridemic men with and without coronary artery disease. Metabolism. 1999;48:301–7. doi: 10.1016/s0026-0495(99)90076-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karpe F. Postprandial lipoportein metabolism and atherosclerosis. J Internal Med. 1999;246:341–55. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1999.00548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Semb H, Olivecrona T. Nutritional regulation of lipoprotein lipase in guinea pig tissue. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1986;876:249–55. doi: 10.1016/0005-2760(86)90281-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ong JM, Kern PA. Effect of feeding and obesity on lipoprotein lipase activity, immunoreactive protein, and messenger RNA levels in human adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:305–11. doi: 10.1172/JCI114155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Frayn KN, Shadid S, Hamlani R, et al. Regulation of fatty acid movement in human adipose tissue in the postabsorbtive-topostprandial transition. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:E308–17. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1994.266.3.E308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakajima K, Kobayashi J, Mabuchi H, et al. Association of angiopoietin-like protein 3 with hepatic triglyceride lipase and lipoprotein lipase activities in human plasma. Ann Clin Biochem. 2010;47:423–31. doi: 10.1258/acb.2010.009307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Murase T, Itakura H. Accumulation of intermediate density lipoprotein in plasma after intravenous administration of hepatic triglyceride lipase antibody in rats. Atherosclerosis. 1981;39:293–300. doi: 10.1016/0021-9150(81)90015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goldberg IJ, Le NA, Paterniti JR, Ginsberg HN, Lindgren FT, Brown WV. Lipoprotein metabolism during acute inhibition of hepatic triglyceride lipase in the cynomolgus monkey. J Clin Invest. 1982;70:1184–92. doi: 10.1172/JCI110717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Oi K, Hirano T, Sakai S, Kawaguchi Y, Hosoya T. Role of hepatic lipase in intermediate-density lipoprotein and small, dense low-density lipoprotein formation in hemodialysis patients. Kidney Int Suppl. 1999;71:S227–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.1999.07159.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zambon A, Deeb SS, Pauletto P, Crepaldi G, Brunzell JD. Hepatic lipase: a marker for cardiovascular disease risk and response to therapy. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2003;14:179–89. doi: 10.1097/00041433-200304000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Deeb SS, Zambon A, Carr MC, Ayyobi AF, Brunzell JD. Hepatic lipase and dyslipidemia: interactions among genetic variants, obesity, gender, and diet. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1279–86. doi: 10.1194/jlr.R200017-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Eisenberg S. Remnant lipoprotein metabolism. In: Crepaldi G, Tiengo A, Manzato E, editors. Diabetes, Obesity and Hyperlipidemia: V. The Plurimetabolic Syndrome. New York, NY: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1993. pp. 7–14. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mjøs OD, Faergeman O, Hamilton RL, Havel RJ. Characterization of remnants produced during the metabolism of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins of blood plasma and intestinal lymph in the rat. J Clin Invest. 1975;56:603– 615. doi: 10.1172/JCI108130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pagnan A, Havel RJ, Kane JP, Kotite L. Characterization of human very low density lipoproteins containing two electrophoretic populations: double pre-beta lipoproteinemia and primary dysbetalipoproteinemia. J Lipid Res. 1977;18:613– 622. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cohn JS, Davignon J. Different approaches to the detection and quantification of triglyceride-rich lipoprotein remnants. In: Jacotot B, Mathé D, Fruchart JC, editors. Atherosclerosis XI. Singapore: Elsevier Science; 1998. pp. 771–776. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nakajima K, Nakano T, Moon HD, et al. The correlation between TG vs remnant lipoproteins in the fasting and postprandial plasma of 23 volunteers. Clin Chim Acta. 2009;404:124–7. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2009.03.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Stanhope KL, Schwarz JM, Keim NL, et al. Consuming fructose-sweetened, not glucose-sweetened, beverages increases visceral adiposity and lipids and decreases insulin sensitivity in overweight/obese humans. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:1322–34. doi: 10.1172/JCI37385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mifflin MD, St Jeor ST, Hill LA, Scott BJ, Daugherty SA, Koh YO. A new predictive equation for resting energy expenditure in healthy individuals. Am J Clin Nutr. 1990;51:241–7. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/51.2.241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ooi TC, Cousins M, Ooi DS, et al. Postprandial remnant-like lipoproteins in hypertriglyceridemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2001;86:3134–42. doi: 10.1210/jcem.86.7.7627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ai M, Tanaka A, Ogita K, et al. Relationship between plasma insulin concentration and plasma remnant lipoprotein response to an oral fat load in patients with type 2 diabetes. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;38:1628–32. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(01)01611-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sekihara T, Nakano T, Nakajima K. High postprandial plasma remnant-like particles-cholesterol in patients with coronary artery diseases on chronic maintenance hemodialysis. Jpn J Nephrol. 1996;38:220–228. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nakano T, Tanaka A, Okazaki M, Tokita Y, Nagamine T, Nakajima K. Particle size of apoB-48 carrying lipoproteins in remnant lipoproteins isolated from postprandial plasma. Ann Clin Biochem. 2011;48:57–64. doi: 10.1258/acb.2010.010193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanaka A, Tomie N, Nakano T, et al. Measurement of postprandial remnant-like particles (RLP) following a fat-loading test. Clin Chim Acta. 1998;275:43–52. doi: 10.1016/s0009-8981(98)00073-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ginsberg HN, Karmally W, Siddiqui M, et al. A dose-response study of the effects of dietary cholesterol on fasting and postprandial lipid and lipoprotein metabolism in healthy young men. Arterioscler Thromb. 1994;14:576–86. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.14.4.576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dubois C, Armand M, Mekki N, et al. Effects of increasing amounts of dietary cholesterol on postprandial lipemia and lipoproteins in human subjects. Am J Clin Nutrition. 1994;60:374–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dubois C, Armand M, Ferezou J, et al. Postprandial appearance of dietary deuterated cholesterol in the chylomicron fraction and whole plasma in healthy subjects. Am J Clin Nutrition. 1996;64:47–52. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/64.1.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Marcoux C, Tremblay M, Fredenrich A, et al. Plasma remnant-like particle lipid and lipoprotein levels in normolipidemic and hyperlipidemic subjects. Atherosclerosis. 1998;139:161–71. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(98)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marcoux C, Tremblay M, Nakajima K, Davignon J, Cohn JS. Characterization of remnant-like particles isolated by immunoaffinity gel from the plasma of type III and type IV hyperlipidemic patients. J Lipid Res. 1999;40:636–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.McNamara JR, Shah PK, Nakajima K, et al. Remnant lipoprotein cholesterol and triglyceride reference ranges from the Framingham Heart Study. Cin Chem. 1998;44:1224–1232. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Leary ET, Wang T, Baker DJ, et al. Evaluation of an immunoseparation method for quantitative measurement of remnant-like particle-cholesterol in serum and plasma. Clin Chem. 1998;44:2490–2498. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Campos E, Nakajima K, Tanaka A, Havel RJ. Properties of an apolipoprotein E-enriched fraction of triglyceride-rich lipoproteins isolated from human blood plasma with a monoclonal antibody to apolipoprotein B-100. J Lipid Res. 1992;33:369–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.McNamara JR, Shah PK, Nakajima K, et al. Remnant-like particle (RLP) cholesterol is an independent cardiovascular disease risk factor in women: results from the Framingham Heart Study. Atherosclerosis. 2001;154:229–37. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00484-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Karpe F, Boquist S, Tang R, Bond GM, de Faire U, Hamsten A. Remnant lipoproteins are related to intima-media thickness of the carotid artery independently of LDL cholesterol and plasma triglycerides. J Lipid Res. 2001;42:17–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ikewaki K, Shige H, Nakajima K, Nakamura H. Postprandial remnant-like particles and coronary artery disease. In: Woodford FP, Davignon J, Sniderman A, editors. Atherosclerosis X. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier; 1995. pp. 200–202. [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shimizu H, Mori M, Sato T, et al. An increase of serum remnant-like particles in noninsulin-dependent diabetic patients with microalbuminuria. Clin Chim Acta. 1993;221:191–196. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(93)90033-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nakajima K, Saito T, Tamura A, et al. A new approach for the detection of type III hyperlipoproteinemia by RLP-cholesterol assay. J Atheroscler Thromb. 1994;1:30–36. doi: 10.5551/jat1994.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wang T, Nakajima K, Leary ET, et al. Ratio of remnant-like particle-cholesterol to serum total triglycerides is an effective alternative to ultracentrifugal and electrophoretic methods in the diagnosis of familial type III hyperlipoproteinemia. Clin Chem. 1999;45:1981–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Oda H, Yorioka N, Okushin S, Nishida Y, Kushihata S, Ito T, Yamakido M. Remnant-like particles cholesterol may indicate atherogenic risk in patients on chronic hemodialysis. Nephron. 1997;76:7–14. doi: 10.1159/000190133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Tanaka A, Ejiri N, Fujinuma Y, et al. Remnant-like particles and restenosis of coronary arteries after PTCA. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;748:595–598. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb17369.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Nakamura H, Ikewaki K, Nishiwaki M, Shige H. Postprandial hyperlipidemia and coronary artery disease. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1995;748:441– 446. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb17340.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Devaraj S, Vega G, Lange R, Grundy SM, Jialal I. Remnant-like particle cholesterol levels in patients with dysbetalipoproteinemia or coronary artery disease. Am J Med. 1998;104:445– 450. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00089-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Takeichi S, Nakajima Y, Osawa M, et al. The possible role of remnant-like particles as a risk factor for sudden cardiac death. Int J Legal Med. 1997;110:213–219. doi: 10.1007/s004140050070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Tomono S, Kawazu S, Kato N, et al. Uptake of remnant like particles (RLP) in diabetic patients from mouse peritoneal macrophages. J Atheroscler Thromb. 1994;1:98–102. doi: 10.5551/jat1994.1.98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Knöfler R, Nakano T, Nakajima K, Takada Y, Takada A. Remnant-like lipoproteins stimulate whole blood platelet aggregation in vitro. Thromb Res. 1995;78:161–171. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(95)00044-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Mochizuki M, Takada TY, Urano T, et al. The in vivo effects of chylomicron remnant and very low density lipoprotein remnant on platelet aggregation in blood obtained from healthy persons. Thromb Res. 1996;5:583–593. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(96)00033-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Kugiyama K, Doi H, Motoyama T, et al. Association of remnant lipoprotein levels with impairment of endotheliumdependent vasomotor function in human coronary arteries. Circulation. 1998;97:2519–2526. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.97.25.2519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Nakajima K, Nakano T, Tanaka A. The oxidative modification hypothesis of atherosclerosis: the comparison of atherogenic effects on oxidized LDL and remnant lipoproteins in plasma. Clin Chim Acta. 2006;367:36–47. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2005.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Hara I, Okazaki M. High-performance liquid chromatography of serumlipoproteins. Methods Enzymol. 1986;129:57–78. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(86)29062-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Usui S, Nakamura M, Jitsukata K, Nara M, Hosaki S, Okazaki M. Assessment of between-instrument variations in a HPLC method for serum lipoproteins and its traceability to reference methods for total cholesterol and HDL-cholesterol. Clin Chem. 2000;46:63–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Usui S, Hara Y, Hosaki S, Okazaki M. A new on-line dual enzymatic method for simultaneous quantification of cholesterol and triglycerides in lipoproteins by HPLC. J Lipid Res. 2002;43:805–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Okazaki M, Usui S, Ishigami M, et al. Identification of unique lipoprotein subclasses for visceral obesity by component analysis of cholesterol profile in high-performance liquid chromatography. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2005;25:578–584. doi: 10.1161/01.ATV.0000155017.60171.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Uchida Y, Kurano Y, Ito S. Establishment of monoclonal antibody against human apo B-48 and measurement of apo B-48 in serum by ELISA method. Clin Lab Anal. 1998;12:89–292. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1998)12:5<289::AID-JCLA7>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sakai N, Uchida Y, Ohashi K, et al. Measurement of fasting serum apoB-48 levels in normolipidemic and hyperlipidemic subjects by ELISA. J Lipid Res. 2003;44:1256–62. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M300090-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Yao Z, Blackhart BD, Linton MF, Taylor SM, Young SG, McCarty BJ. Expression of carboxyl-terminally truncated forms of human apolipoprotein B in rat hepatoma cells. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:3300–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Otokozawa S, Ai M, Diffenderfer MR, et al. Fasting and postprandial apolipoprotein B-48 levels in healthy, obese, and hyperlipidemic subjects. Metabolism. 2009;58:1536–42. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2009.04.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Nakano T, Nakajima K, Niimi M, et al. Determination of apolipoproteins B-48 and B-100 carrying particles in lipoprotein fractions extracted from human aortic atherosclerotic plaques in sudden cardiac death cases. Clin Chim Acta. 2008;390:38–43. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2007.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Fielding CJ, Havel RJ, Todd KM, et al. Effects of dietary cholesterol and fat saturation on plasma lipoproteins in an ethnically diverse population of healthy young men. J Clin Invest. 1995;95:611–618. doi: 10.1172/JCI117705. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Deighan CJ, Caslake MJ, McConnell M, Boulton-Jones JM, Packard CJ. The atherogenic lipoprotein phenotype: small dense LDL and lipoprotein remnants in nephrotic range proteinuria. Atherosclerosis. 2001;157:211–20. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9150(00)00710-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Inazu A, Nakajima K, Nakano T, et al. Decreased post-prandial triglyceride response and diminished remnant lipoprotein formation in cholesteryl ester transfer protein (CETP) deficiency. Atherosclersois. 2008;196:953–57. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2007.02.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ai M, Tanaka A, Shimokado K, et al. A deficiency of cholesteryl ester transfer protein whose serum remnant-like particle-triglyceride significantly increased, but serum remnant-like particle-cholesterol did not after an oral fat load. Ann Clin Biochem. 2009;46:457–63. doi: 10.1258/acb.2009.008249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]