Abstract

Objective

We assessed individual- and community-level disparities and trends in birth outcomes and infant mortality among First Nations (North American Indians) and Inuit versus other populations in Quebec, Canada.

Methods

A retrospective birth cohort study of all births to Quebec residents, 1991–2000. At the individual level, we examined outcomes comparing births to First Nations and Inuit versus other mother tongue women. At the community level, we compared outcomes among First Nations and Inuit communities versus other communities.

Results

First Nations and Inuit births were much less likely to be small-for-gestational-age but much more likely to be large-for-gestational-age compared to other births at the individual or community level, especially for First Nations. At both levels, Inuit births were 1.5 times as likely to be preterm. At the individual level, total fetal and infant mortality rates were 2 times as high for First Nations, and 3 times as high for Inuit. Infant mortality rates were 2 times as high for First Nations, and 4 times as high for Inuit. There were no reductions in these disparities between 1991–1995 and 1996–2000. Modestly smaller disparities in total fetal and infant mortality were observed for First Nations at the community level (risk ratio=1.6), but for Inuit there were similar disparities at both levels. These disparities remained substantial after adjusting for maternal characteristics.

Conclusion

There were large and persistent disparities in fetal and infant mortality among First Nations and Inuit versus other populations in Quebec based on individual- or community-level assessments, indicating a need to improve socioeconomic conditions as well as perinatal and infant care for Aboriginal peoples.

Keywords: Health disparities, aboriginal people, preterm birth, fetal growth, fetal and infant mortality

INTRODUCTION

Indigenous people worldwide experience disparities in maternal and infant health determinants and outcomes compared to non-Indigenous populations [1,2]. Substantially higher infant mortality rates have been reported among Indigenous compared to non-Indigenous populations even in developed countries including Australia, Canada, New Zealand and the United States [3–17].

Although significant improvements have been made over the past decades in maternal and infant health in Canada, mainly due to improved living conditions and better health care, the relative disparities largely persist and present a major challenge. In Canada, the Constitution Act (1982) recognizes and re-affirms the Aboriginal rights of three groups of Aboriginal peoples: Indians (alternative terms: “North American Indians”, “First Nations”), Inuit and Métis. The federal Indians Act defines the term “Status Indians” in reference to registered Indians. For this article, the term First Nations includes “Status Indians” living on- or off-reserve as well as “non-Status” Indians.

Population-based data on Aboriginal birth outcomes suffer from a lack of individual-level Aboriginal birth identifiers in most provinces in Canada [10,18]. Of the few provinces with an Aboriginal birth identifier, the identifier may provide only incomplete coverage of Aboriginal births, or may have missed a significant proportion of total Aboriginal births. For example, Métis and non-Status Indian groups are almost always excluded. In Quebec, where First Nations and Inuit births can only be identified by maternal mother tongue recorded on birth registrations [10]. However, about 40% of self-identified First Nations and 14% of self-identified Inuit in Quebec no longer spoke a native mother tongue, according to the 2001 census, indicating that significant numbers of Inuit and especially First Nations births would have been missed using the mother tongue identifier.

In Canada, the overwhelming majority of residents of First Nation reserves and northern Inuit communities are First Nations and Inuit, respectively. This creates a unique opportunity to assess Aboriginal birth outcomes at the community level which may provide useful information for developing targeted community-level perinatal and infant health promotion programs. Such information may be particularly relevant for First Nations and Inuit in Quebec, since about 63% of First Nations live on Indian reserves and 94% of Inuit live in Inuit communities in the Nunavik region, respectively, according to the 2001 census. The total Aboriginal population (by self identification) in Quebec numbered approximately 79,000, accounting for about 1.1% of the total population, including approximately 52,000 First Nations, 17,000 Métis, and 10,000 Inuit. We sought to determine the disparities and trends in birth outcomes and infant mortality comparing First Nations, Inuit and other populations at the individual and community levels in Quebec. We could not address Métis birth outcomes since Métis births could not be identified at the individual or community level.

STUDY DESIGN

Subjects

This was a retrospective birth cohort study of all births (n=840,683) in Quebec 1991–2000, using the linked stillbirth, live birth and infant death databases at Statistics Canada. The linkage of the birth and infant death records was sponsored by the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System (CPSS). We used data for the period 1991–2000 because those were the most recent data available when the study was approved by the research ethics board. Available maternal and pregnancy characteristics for births in Quebec in the databases include infant sex (boy versus girl), parity (primiparous versus multiparous), plurality (singleton versus multiple), gestational age (in completed weeks), birth weight (g), maternal age (<10, 20–34, ≥35 years), education (<completed high school, completed high school, and ≥some college), marital status (single, common-law union, married), mother tongue and place of residence.

The validity of the Canadian linked vital data has been well documented [19]. The study was approved by the research ethics board of Sainte-Justine Hospital, University of Montreal, the First Nations of Quebec and Labrador Health and Social Service Commission, and the Nunavik Nutrition and Health Committee. Informed consent was not sought from individual participants because the study was based on anonymized linked birth data.

Individual-Level Aboriginal Birth Identifier

We identified First Nations, Inuit and other births by the maternal mother tongue as recorded on birth registrations [10]. If the maternal mother tongue was missing and paternal mother tongue was not missing, then the maternal mother tongue was taken to be the same as the paternal mother tongue. Mother tongue was missing for 16,496 births (2%), leaving 824,187 births available for the individual-level analyses. Births were grouped into three mutually exclusive maternal mother tongue groups: First Nations (5,184), Inuit (2,527), and others (816,476). The other mother tongue group served as the reference group, and consisted of French, English and other mother tongues because their differences in birth outcomes and infant mortality were small, and they all had much lower rates of adverse birth outcomes compared to First Nations and Inuit births [10].

Aboriginal Community Identifier

We used geocoding to determine whether each birth was to a mother residing in a First Nations, Inuit, or other community (mutually exclusive areas) in Quebec. We restricted the Aboriginal community-level analyses to First Nations communities on reserve and Inuit communities in Nunavik only, because births to residents in off-reserve Aboriginal communities and among Inuit and First Nations living in southern communities could not be identified. Community type was determined by the maternal residential postal code as recorded on birth registrations, using geocoding software and files developed by Statistics Canada [20]. If postal codes were unavailable (5%), municipality codes were used instead. There were a total of 14 Inuit communities in the Nunavik region, all served by postal codes unique to Aboriginal communities. There were a total of 40 First Nations communities (reserves) in Quebec, 21 served by postal codes unique to First Nations communities, and 19 served by postal codes shared with non-Aboriginal communities; all were considered First Nations communities. When postal codes were unavailable, we used census sub-division codes derived from municipality name to identify births to residents of Inuit and First Nations communities, if the census subdivision code was unique to a First Nations or Inuit community. A birth was considered to belong to a First Nations or Inuit community if the maternal place of residence was identified as a First Nations or Inuit community by either postal code or census sub-division code. The rest were considered births to mothers of other communities (residual areas, “non-Aboriginal” communities). There were 255 births (0.03%) without sufficient information on the place of residence for determining community type, leaving 840,428 births available for the community-level analyses.

Birth Outcomes

Birth outcomes under study included preterm (<37 completed weeks gestational age), small-for-gestational-age (<10th percentile in birth weight for gestational age using the Canadian standards [21]), low birth weight (<2500 g) and large-for-gestational-age (>90th percentile) births, stillbirth (fetal deaths ≥20 weeks and ≥500 g), neonatal death (died at 0–27 days of life), postneonatal death (at 28–364 days of life), infant death (at 0–364 days of life), and total fetal and infant death (stillbirths + infant deaths). For stillbirth and total fetal and infant mortality, rates were calculated per 1000 total births (live births + stillbirths). Infant mortality rates were calculated per 1000 live births.

Statistical Analyses

Crude rates and relative risks (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were calculated for birth and infant outcomes comparing First Nations and Inuit versus other births at the individual and community levels. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (OR) with 95% CIs were calculated to assess whether the differences could be explained by the observed maternal characteristics (maternal age, parity, marital status, education). All data analyses were carried out using SAS, Version 9.1.

RESULTS

Individual-Level Disparities in Birth Outcomes

Compared to births to the majority “other mother tongue” group, both First Nations and Inuit births were much less likely to be small-for-gestational-age (RR=0.3 for First Nations, RR=0.5 for Inuit), and much more likely to be large-for-gestational-age (RR=3.2 for First Nations, RR=1.8 for Inuit), especially for First Nations (Table 1). Rates of pre-term birth were 1.5 times as high for Inuit, but slightly lower for First Nations. Total fetal and infant mortality rates were 2.0 times as high for First Nations, and 3.1 times as high for Inuit. Stillbirth rates were 2.0 times as high for First Nations, and 1.8 times as high for Inuit births. Infant mortality rates were 2 times as high for First Nations and 4 times as high for Inuit infants compared to infants of other mother tongue women. The elevated risk of infant death among First Nations births was almost exclusively due to the much higher postneonatal mortality (3.8 times as high). In contrast, substantially elevated risks of both neonatal (2.5 times as high) and postneonatal (7.8 times as high) death were observed for Inuit infants.

Table 1.

Birth Outcomes and Infant Mortality among First Nations, Inuit and Other Populations at the Individual and Community Levels in Quebec, 1991–2000

| Outcome | Others | First Nations | Inuit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Rate | Rate | RR (95% CI) | Rate | RR (95% CI) | |

|

| |||||

| Individual-level (n, births by maternal mother tongue) | (816,476) | (5,184) | (2,527) | ||

| Births, % | |||||

| Preterm | 7.2 | 6.7 | 0.92 (0.83, 1.02) | 10.8 | *1.49 (1.33, 1.67) |

| Small-for-gestational-age | 10.7 | 3.6 | *0.34 (0.29, 0.39) | 5.8 | *0.54 (0.46, 0.64) |

| Low birth weight | 6.0 | 3.1 | *0.53 (0.45, 0.61) | 6.1 | 1.02 (0.87, 1.19) |

| Large-for-gestational-age | 8.5 | 27.6 | *3.23 (3.09, 3.38) | 15.1 | *1.77 (1.61, 1.94) |

| Deaths, per 1000 | |||||

| Stillbirth | 3.6 | 7.1 | *1.98 (1.43, 2.74) | 6.3 | *1.76 (1.08, 2.87) |

| Infant death | 4.4 | 8.7 | *1.96 (1.46, 2.63) | 18.7 | *4.27 (3.21, 5.68) |

| Neonatal death | 2.9 | 3.1 | 1.07 (0.66, 1.75) | 7.2 | *2.47 (1.56, 3.92) |

| Postneonatal death | 1.5 | 5.7 | *3.81 (2.64, 5.50) | 11.6 | *7.84 (5.43, 11.3) |

| Fetal and infant death | 8.0 | 15.8 | *1.99 (1.60, 2.46) | 24.9 | *3.13 (2.45, 4.00) |

| Community-level (n, births by community) | (825,940) | (11,845) | (2,898) | ||

| Births, % | |||||

| Preterm | 7.3 | 7.3 | 1.00 (0.94, 1.07) | 10.8 | *1.48 (1.33, 1.64) |

| small-for-gestational-age | 10.7 | 5.6 | *0.52 (0.48, 0.54) | 5.5 | *0.51 (0.44, 0.59) |

| Low birth weight | 6.0 | 4.6 | *0.76 (0.70, 0.82) | 6.1 | 1.01 (0.87, 1.16) |

| Large-for-gestational-age | 8.5 | 21.9 | *2.54 (2.45, 2.63) | 16.2 | *1.90 (1.85, 2.07) |

| Deaths, per 1000 | |||||

| Stillbirth | 3.8 | 5.6 | *1.47 (1.15, 1.88) | 7.6 | *2.01 (1.32, 3.04) |

| Infant death | 4.4 | 7.8 | *1.88 (1.45, 2.19) | 18.4 | *4.21 (3.22, 5.51) |

| Neonatal death | 2.9 | 3.7 | 1.23 (0.93, 1.70) | 7.3 | *2.52 (1.64, 3.86) |

| Postneonatal death | 1.5 | 4.2 | *2.83 (2.13, 3.76) | 11.2 | *7.59 (5.35, 10.8) |

| Fetal and infant death | 8.1 | 13.3 | *1.64 (1.40, 1.92) | 25.9 | *3.18 (2.54, 3.98) |

RR=risk ratio; CI= 95% confidence intervals.

P<0.05

Community-Level Disparities in Birth Outcomes

Very similar disparities in birth outcomes and infant mortality were observed comparing Inuit versus other births at the community level (Table 1, lower panel) as those observed at the individual level. In contrast, the relative risks (RRs) comparing First Nations versus other births were “blunted” for most outcomes at the community level: the RRs decreased from 3.3 to 2.5 for large-for-gestational-age birth, from 2.0 to 1.5 for stillbirth, and from 2.0 to 1.6 for total fetal and infant death. However, the RRs for infant mortality changed very little comparing First Nations versus other infants: the RR was close to 2.0 in both the individual- and community-level comparisons.

Trends in Disparities

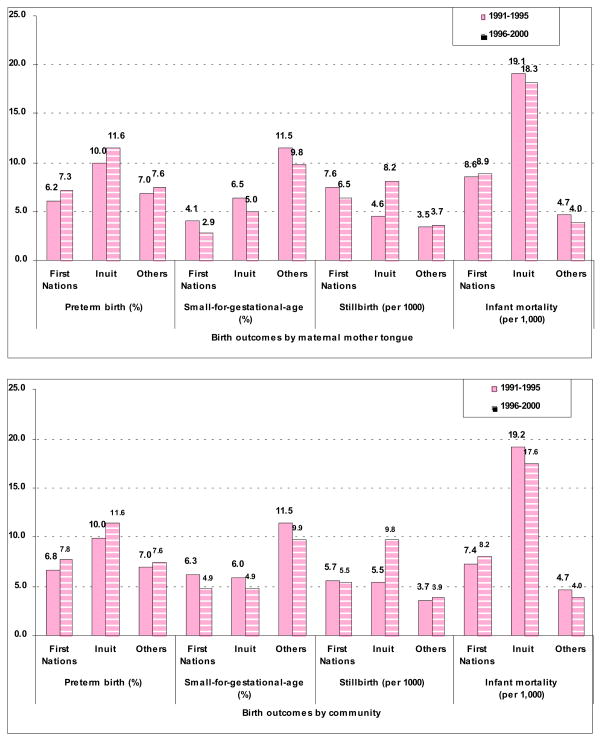

At both the individual and community levels, there were no improvements in disparities in fetal and infant mortality comparing First Nations or Inuit versus other populations from 1991–1995 to 1996–2000, and for some outcomes the disparities may have even been worse in the more recent period (Tables 2 and 3, Fig. 1). The RRs for total fetal and infant mortality comparing First Nations versus other births remained at 2.0 in both periods at the individual level, and increased slightly from 1.6 to 1.7 at the community level, while the RRs comparing Inuit versus other births increased from 2.9 in 1991–1995 to 3.4 in 1996–2000 at both levels. The disparities in infant mortality comparing First Nations versus other infants increased over time from 1991–1995 to 1996–2000 at both levels: the RRs increased from 1.8 to 2.2 at the individual level, and from 1.5 to 2.1 at the community level. The disparities (RRs) in infant mortality comparing Inuit versus other infants changed little in the two periods at either level. The disparities in stillbirth rates comparing Inuit versus other births increased over time from 1991–1995 to 1996–2000 at both levels: the RRs increased from 1.3 (not statistically significant) to 2.2 (statistically significant) at the individual level, and from 1.5 (not statistically significant) to 2.5 (statistically significant) at the community level.

Table 2.

Birth Outcomes and Infant Mortality among First Nations, Inuit and Other Mother Tongue Populations in Quebec, 1991–1995 and 1996–2000

| Outcome | Mother tongue – Others, | Mother tongue - First Nations | Mother tongue – Inuit | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Rate | Rate | RR (95% CI) | Rate | RR (95% CI) | |

|

| |||||

| 1991–1995 (n, births) | (442,180) | (3,044) | (1,314) | ||

| Births, % | |||||

| Preterm | 7.0 | 6.2 | 0.89 (0.77, 1.02) | 10.0 | *1.44 (1.23, 1.70) |

| Small-for-gestational-age | 11.5 | 4.1 | *0.36 (0.30, 0.42) | 6.5 | *0.57 (0.47, 0.70) |

| Low birth weight | 6.0 | 3.1 | *0.53 (0.43, 0.64) | 5.2 | 0.86 (0.68, 1.09) |

| Large-for-gestational-age | 8.1 | 26.7 | *3.30 (3.11, 3.51) | 15.3 | *1.89 (1.67, 2.15) |

| Deaths, per 1000 | |||||

| Stillbirth | 3.5 | 7.6 | *2.15 (1.43, 3.24) | 4.6 | 1.30 (0.58, 2.89) |

| Infant death | 4.7 | 8.6 | *1.83 (1.24, 2.68) | 19.1 | *4.05 (2.74, 5.99) |

| Neonatal death | 3.1 | 2.3 | 0.74 (0.36, 1.55) | 7.6 | *2.44 (1.31, 4.54) |

| Postneonatal death | 1.6 | 6.3 | *3.97 (2.52, 6.26) | 11.6 | *7.28 (4.38, 12.1) |

| Fetal and infant death | 8.2 | 16.1 | *1.96 (1.48, 2.59) | 23.6 | *2.87 (2.03, 4.07) |

| 1996–2000 (n, births) | (374,296) | (2,140) | (1,213) | ||

| Births, % | |||||

| Preterm | 7.6 | 7.3 | 1.04 (0.88, 1.22) | 11.6 | *1.53 (1.31, 1.79) |

| Small-for-gestational-age | 9.8 | 2.9 | *0.30 (0.24, 0.38) | 5.0 | *0.51 (0.40, 0.65) |

| Low birth weight | 6.0 | 4.6 | *0.52 (0.41, 0.66) | 7.1 | 1.19 (0.97, 1.46) |

| Large-for-gestational-age | 9.1 | 28.8 | *3.18 (2.98, 3.40) | 14.9 | *1.64 (1.44, 1.88) |

| Deaths, per 1000 | |||||

| Stillbirth | 3.7 | 6.5 | *1.77 (1.05, 2.98) | 8.2 | *2.22 (1.20, 4.13) |

| Infant death | 4.0 | 8.9 | *2.24 (1.43, 3.52) | 18.3 | *4.59 (3.02, 6.96) |

| Neonatal death | 2.6 | 4.2 | 1.61 (0.84, 3.10) | 6.7 | *2.53 (1.27, 5.07) |

| Postneonatal death | 1.4 | 4.7 | *3.47 (1.86, 6.47) | 11.7 | *8.59 (5.07, 14.6) |

| Fetal and infant death | 7.7 | 15.4 | *2.01 (1.43, 2.82) | 26.4 | *3.44 (2.44, 4.85) |

RR=risk ratio; CI= 95% confidence intervals.

P<0.05

Table 3.

Birth Outcomes and Infant Mortality in First Nations, Inuit and Other Communities in Quebec, 1991–1995 and 1996–2000

| Outcome | Other Communities | First Nations Communities | Inuit Communities | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Rate | Rate | RR (95% CI) | Rate | RR (95% CI) | |

|

| |||||

| 1991–1995 (n, births) | (448,617) | (6,109) | (1,465) | ||

| Births, % | |||||

| Preterm | 7.0 | 6.8 | 0.97 (0.89, 1.07) | 10.0 | *1.42 (1.22, 1.66) |

| Small-for-gestational-age | 11.5 | 6.3 | *0.55 (0.50, 0.60) | 6.0 | *0.52 (0.43, 0.64) |

| Low birth weight | 6.0 | 4.6 | *0.77 (0.69, 0.86) | 4.8 | 0.80 (0.64, 1.01) |

| Large-for-gestational-age | 8.1 | 20.4 | *2.52 (2.40, 2.65) | 16.0 | *1.97 (1.75, 2.22) |

| Deaths, per 1000 | |||||

| Stillbirth | 3.7 | 5.7 | *1.54 (1.11, 2.16) | 5.5 | 1.47 (0.64, 4.94) |

| Infant death | 4.7 | 7.4 | *1.57 (1.17, 2.11) | 19.2 | *4.08 (2.82, 5.90) |

| Neonatal death | 3.1 | 3.3 | 1.06 (0.68, 1.64) | 7.6 | *2.42 (1.31, 4.37) |

| Postneonatal death | 1.6 | 4.1 | *2.58 (1.74, 3.85) | 11.8 | *7.36 (4.56, 11.9) |

| Fetal and infant death | 8.4 | 13.1 | *1.56 (1.25, 1.94) | 24.6 | *2.92 (2.11, 4.04) |

| 1996–2000 (n, births) | (377,323) | (5,736) | (1,433) | ||

| Births, % | |||||

| Preterm | 7.6 | 7.8 | 1.02 (0.94, 1.12) | 11.6 | *1.52 (1.31, 1.75) |

| Small-for-gestational-age | 9.9 | 4.9 | *0.50 (0.44, 0.56) | 4.9 | *0.50 (0.39, 0.62) |

| Low birth weight | 6.0 | 4.5 | *0.75 (0.66, 0.84) | 7.3 | 1.21 (1.01, 1.46) |

| Large-for-gestational-age | 9.0 | 22.9 | *2.54 (2.41, 2.66) | 16.4 | *1.64 (1.44, 1.88) |

| Deaths, per 1000 | |||||

| Stillbirth | 3.9 | 5.4 | 1.39 (0.98, 1.99) | 9.8 | *2.52 (1.49, 4.25) |

| Infant death | 4.0 | 8.2 | *2.07 (1.55, 2.77) | 17.6 | *4.44 (3.00, 6.56) |

| Neonatal death | 2.6 | 4.0 | *1.53 (1.01, 2.31) | 7.0 | *2.67 (1.43, 4.96) |

| Postneonatal death | 1.3 | 4.2 | *3.17 (2.10, 4.77) | 10.6 | *7.98 (4.79, 13.3) |

| Fetal and infant death | 7.8 | 13.6 | *1.74 (1.39, 2.17) | 27.4 | *3.47 (2.54, 4.74) |

RR=risk ratio; CI= 95% confidence intervals.

P<0.05.

Fig. 1.

Birth Outcomes and Infant Mortality by Individual- and Community-level Aboriginal Birth Identifiers in Quebec, 1991–1995 and 1996–2000.

Adjusted Odds Ratios

As compared to the crude ORs, the adjusted ORs showed similar risk patterns, but smaller disparities in fetal and infant mortality comparing First Nations or Inuit versus other births at both the individual and community levels (Table 4). After the adjustments, the ORs comparing First Nations versus other births decreased from 2.0 to 1.5 for infant death, from 3.8 to 2.0 for postneonatal death, and from 2.0 to 1.6 for total fetal and infant death at the individual level, while the ORs decreased from 1.8 to 1.5 for infant death, from 2.8 to 2.0 for postneonatal death, and from 1.7 to 1.4 for total fetal and infant death at the community level. The decreases from crude to adjusted ORs for adverse birth and infant outcomes comparing Inuit versus other births were similar at the individual and community levels. For example, after the adjustments, the ORs for preterm birth comparing Inuit versus other births decreased from 1.6 to 1.2 at the individual level, and from 1.5 to 1.2 at the community level. The lower risks of small-for-gestational-age and low birth weight births but higher risk of large-for-gestational-age birth among First Nations were even more striking after the adjustments.

Table 4.

Crude and Adjusted Odds Ratios (OR) of Birth Outcomes and Infant Mortality Comparing First Nations and Inuit versus Others at the Individual and Community Levels in Quebec, 1991–2000

| First Nations | Inuit | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| cOR (95% CI) | § aOR (95% CI) | cOR (95% CI) | § aOR (95% CI) | |

|

| ||||

| Individual-level | ||||

| Preterm birth | 0.91 (0.82, 1.02) | *0.78 (0.70, 0.87) | *1.55 (1.37, 1.76) | *1.22 (1.05, 1.42) |

| Small-for-gestational-age | *0.31 (0.27, 0.36) | *0.26 (0.22, 0.30) | *0.51 (0.44, 0.61) | *0.42 (0.35, 0.51) |

| Low birth weight | *0.51 (0.44, 0.60) | *0.41 (0.35, 0.48) | 1.02 (0.87, 1.20) | *0.77 (0.64, 0.93) |

| Large-for-gestational-age | *4.08 (3.84, 4.34) | *4.53 (4.24, 4.83) | *1.91 (1.71, 2.13) | *2.13 (1.87, 2.42) |

| Stillbirth | *1.99 (1.44, 2.75) | *1.70 (1.16, 2.48) | *1.76 (1.08, 2.89) | 0.87 (0.39, 1.94) |

| Infant death | *2.01 (1.49, 2.69) | *1.45 (1.06, 1.98) | *4.34 (3.24, 5.80) | *2.79 (1.94, 4.00) |

| Neonatal death | 1.07 (0.66, 1.75) | 1.00 (0.61, 1.65) | *2.48 (1.56, 3.95) | 1.75 (0.96, 3.17) |

| Postneonatal death | *3.82 (2.64, 5.53) | *2.00 (1.33, 3.00) | *7.92 (5.47, 11.5) | *4.11 (2.11, 6.45) |

| Fetal and infant death | *2.00 (1.61, 2.49) | *1.55 (1.21, 1.97) | *3.18 (2.48, 4.09) | *2.06 (1.48, 2.86) |

| Community-level | ||||

| Preterm birth | 1.00 (0.93, 1.07) | *0.92 (0.85, 0.99) | *1.53 (1.36, 1.73) | *1.19 (1.04, 1.38) |

| Small-for-gestational-age | *0.49 (0.46, 0.53) | *0.42 (0.38, 0.45) | *0.48 (0.41, 0.56) | *0.40 (0.33, 0.48) |

| Low birth weight | *0.75 (0.68, 0.81) | *0.63 (0.58, 0.70) | 1.01 (0.86, 1.17) | *0.74 (0.61, 0.89) |

| Large-for-gestational-age | *2.96 (2.83, 3.09) | *3.29 (3.13, 3.45) | *2.07 (1.88, 2.29) | *2.36 (2.11, 2.65) |

| Stillbirth | *1.47 (1.15, 1.88) | 1.32 (0.97, 1.79) | *2.01 (1.32, 3.07) | 1.42 (0.78, 2.59) |

| Infant death | *1.79 (1.46, 2.21) | *1.51 (1.20, 1.89) | *4.27 (3.25, 5.62) | *2.85 (2.03, 4.00) |

| Neonatal death | 1.26 (0.93, 1.70) | 1.19 (0.86, 1.66) | *2.53 (1.64, 3.89) | 1.85 (1.07, 3.20) |

| Postneonatal death | *2.83 (2.13, 3.77) | *1.95 (1.43, 2.67) | *7.66 (5.38, 10.9) | *4.18 (2.72, 6.43) |

| Fetal and infant death | *1.65 (1.40, 1.93) | *1.44 (1.20, 1.83) | *3.24 (2.57, 4.07) | *2.31 (1.72, 3.10) |

cOR=crude odds ratio; aOR=adjusted odds ratio; CI= 95% confidence intervals.

The ORs were adjusted for maternal age (<20, 20–34, 35+), education (<completed high school, completed high school, and ≥some college), marital status (single, common-law union, married), parity (primiparous, multiparous), infant sex and multiple pregnancy (singleton, multiple), using other births as the reference group.

P<0.05.

DISCUSSION

Major Findings

We observed substantial and persistent disparities in birth outcomes and infant mortality among First Nations and Inuit versus other populations in both individual- and community-level comparisons in Quebec. The findings strongly imply a need for improved socioeconomic and living conditions, and more effective and culturally accessible perinatal and infant health promotion programs for Aboriginal peoples to reduce adverse birth and infant outcomes.

Comparisons with Findings from Previous Studies

Our study confirmed the persistent and substantial disparities in birth outcomes and infant mortality among Canadian First Nations and Inuit versus other populations in Canada [10,11]. In addition, we observed even wider disparities in infant mortality comparing First Nations or Inuit versus other infants in the more recent period. This trend is strikingly similar to that observed in a recent study comparing infant mortality rates among Aboriginal versus non-Aboriginal populations in Western Australia [6]. These findings underscore the need for efforts to improve the health and living standards of Indigenous populations worldwide.

To our knowledge, our study is the first to examine disparities in birth outcomes and infant mortality among Indigenous and non-Indigenous populations at both the individual and community levels. While limited in scope, the community-level approach may provide a useful perspective in public health surveillance - in the absence of individual-level Aboriginal identifiers in population-based health data for most Canadian provinces and other countries or regions. Community-level information provides important data that are relevant to community-oriented public health intervention programs. However, community-level differences may be regional-specific, and our results may not be applicable to other regions. In our study, the accuracy of our geocoding-based determination of community type was very precise for all Inuit communities but not so precise for some First Nations communities. However, even such less precise estimates for First Nations on reserve communities may provide important information for perinatal health surveillance, and would provide conservative estimates of adverse birth outcomes among First Nations communities (since non-First Nations within the “First Nations communities” were expected to have better birth outcomes). Community-level data on Aboriginal birth outcomes can provide important information complementary to individual-level data based on the maternal mother tongue identifier in Quebec, since 40% First Nations no longer speak a First Nations mother tongue.

Limitations

We could not identify any Métis births at the individual or community level in Quebec, resulting in their being mis-classified into the much larger non-Aboriginal group. At the individual level, we estimated that some Inuit (about 14%) and many First Nations (about 40%) women likely did not report an Inuit or a First Nations mother tongue, resulting in their being classified into the other “non-Aboriginal” mother tongue group. However, because of the much larger size of the latter reference group, such “misclassification” with respect to Aboriginal self-identification is unlikely to have significantly impacted the observed disparities. At the community level, some First Nations communities shared postal codes with adjacent non-Aboriginal communities. In these cases both First Nations and non-Aboriginal community areas within the postal code were considered as First Nations communities although there were substantial numbers of non-Aboriginal persons in some of those communities. Additionally and we could not identify off reserve Aboriginal communities (as their postal codes were not specific to the Aboriginal communities). The community-level analyses excluded a substantive portion of the Aboriginal population in Quebec including all off reserve First Nations (accounting for 37% all self-identified First Nations), all Métis, and Inuit living outside of Inuit communities (accounted for 6% all self-identified Inuit in Quebec). These limitations would have blunted the disparities in outcomes comparing Aboriginal to non-Aboriginal communities. Our results are specifically relevant to on reserve Aboriginal communities only. Moreover, as community-level information is regional specific, we could not assume that our findings are applicable to other regions and countries. There is a clear need for reliable and valid Aboriginal birth identifiers for more accurate ascertainment of perinatal and infant health inequalities between Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal populations.

SYNOPSIS

There were large and persistent disparities in fetal and infant mortality among Inuit and First Nations versus other populations in Quebec based on individual- or community-level assessments, strongly indicating a need to improve socioeconomic conditions and perinatal and infant care for Aboriginal peoples.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research – Institute of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health (CIHR-IAPH, grant # 73551 – ZC Luo). We are grateful to Statistics Canada and to the Institut de la Statistique du Québec for providing access to the data for the research project. F Simonet was supported by a scholarship from the CIHR Strategic Training Initiative in Research in Reproductive Health Science, and S Wassimi by a studentship from the research grant. Dr. Luo was supported by a Clinical Epidemiology Junior Scholar Award from the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec (FRSQ), and a CIHR New Investigator award in Gender and Health, Dr Heaman by a CIHR Mid-Career Research Chair Award in Gender and Health, Dr. Smylie by a CIHR New Investigator award, Dr. Martens by a CIHR/Public Health Agency of Canada Applied Public Health Chair award, and Dr. Fraser by a CIHR Canada Research Chair award in perinatal epidemiology. Other collaborators and Aboriginal Advisory Board Members include Katherine Minch, University of Toronto, Donna Lyon, Tracey O’Hearn and Catherine Carry, National Aboriginal Health Organization.

References

- 1.Gracey M, King M. Indigenous health part 1: determinants and disease patterns. Lancet. 2009;374(9683):65–75. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60914-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Smylie J, Adomako P. Indigenous Children’s Health Report: Health Assessment in Action. Toronto: St. Michael’s Hospital; 2009. Accessed at http://www.stmichaelshospital.com/crich/in-digenous_childrens_health_report.php. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alessandri LM, Chambers HM, Blair EM, Read AW. Perinatal and postneonatal mortality among Indigenous and non-Indigenous infants born in Western Australia, 1980–1998. Med J Aust. 2001;175(4):185–9. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2001.tb143092.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anonymous, editor. Decrease in infant mortality and sudden infant death syndrome among Northwest American Indians and Alaskan Natives--Pacific Northwest, 1985–1996. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:181–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baldwin LM, Grossman DC, Casey S, Hollow W, Sugarman JR, Freeman WL, Hart LG. Perinatal and infant health among rural and urban American Indians/Alaska Natives. Am J Public Health. 2002;92(9):1491–7. doi: 10.2105/ajph.92.9.1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Freemantle CJ, Read AW, de Klerk NH, McAullay D, Anderson IP, Stanley FJ. Patterns, trends, and increasing disparities in mortality for Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal infants born in Western Australia, 1980–2001: population database study. Lancet. 2006;367(9254):1758–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68771-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Freemantle CJ, Read AW, de Klerk NH, McAullay D, Anderson IP, Stanley FJ. Sudden infant death syndrome and unascertainable deaths: trends and disparities among Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal infants born in Western Australia from 1980 to 2001 inclusive. J Paediatr Child Health. 2006;42(7–8):445–51. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2006.00895.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grossman DC, Krieger JW, Sugarman JR, Forquera RA. Health status of urban American Indians and Alaska Natives. A population-based study. JAMA. 1994;271(11):845–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grossman DC, Baldwin LM, Casey S, Nixon B, Hollow W, Hart LG. Disparities in infant health among American Indians and Alaska natives in US metropolitan areas. Pediatrics. 2002;109(4):627–33. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Luo ZC, Wilkins R, Platt RW, Kramer MS. Risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes among Inuit and North American Indian women in Quebec, 1985–97. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18(1):40–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2003.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo ZC, Kierans WJ, Wilkins R, Liston RM, Uh SH, Kramer MS. Infant mortality among First Nations versus non-First Nations in British Columbia: temporal trends in rural versus urban areas, 1981–2000. Int J Epidemiol. 2004;33(6):1252–9. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Macaulay A, Orr P, Macdonald S, et al. Mortality in the Kivalliq Region of Nunavut, 1987–1996. Int J Circumpolar Health. 2004;63 (Suppl 2):80–5. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v63i0.17819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacMillan HL, MacMillan AB, Offord DR, Dingle JL. Aboriginal health. CMAJ. 1996;155(11):1569–78. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nakamura RM, King R, Kimball EH, Oye RK, Helgerson SD. Excess infant mortality in an American Indian population, 1940 to 1990. JAMA. 1991;266(16):2244–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roder D, Chan A, Priest K. Perinatal mortality trends among South Australian aboriginal births 1981–92. J Paediatr Child Health. 1995;31(5):446–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1995.tb00855.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tomashek KM, Qin C, Hsia J, Iyasu S, Barfield WD, Flowers LM. Infant mortality trends and differences between American Indian/Alaska Native infants and white infants in the United States, 1989–1991 and 1998–2000. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(12):2222–7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.053744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smylie J, Anderson M. Understanding the health of Indigenous peoples in Canada: key methodological and conceptual challenges. CMAJ. 2006;175(6):602. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Smylie J, Pennock J, Fell D, Ohlsson A and the Joint Working Group on First Nations, Indian, Inuit, and Métis Infant Mortality of the Canadian Perinatal Surveillance System. A review of Aboriginal infant mortality rates in Canada – striking and persistent Aboriginal/non-Aboriginal Inequities. Canad J Public Health. doi: 10.1007/BF03404361. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fair M, Cyr M, Allen AC, Wen SW, Guyon G, MacDonald RC. An assessment of the validity of a computer system for probabilistic record linkage of birth and infant death records in Canada. The Fetal and Infant Health Study Group. Chronic Dis Can. 2000;21(1):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wilkins R. Automated geographic coding based on the Statistics Canada Postal Code Conversion files, including postal codes to Septeber 2006. Ottawa: Health Analysis and Measurement Group, Statistics Canada; 2007. Jan, PCCF+ Version 4J User’s Guide. Catalogue no. 82F0086-XDB. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):E35. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]