Abstract

Purpose

Type IIB odontoid fractures (OF) in elderly patients are life-threatening conditions. Optimal treatment of these fractures is still controversial. The aim of this study was to assess the clinical and radiological outcome of surgically treated type IIB OF by anterior screw fixation in octogenarians.

Methods

Eleven octogenarians with type IIB OF were operated using anterior screw fixation. Follow-up assessment included operative mortality and morbidity rates, long-term functional outcome and fracture union and stability.

Results

There was neither operative mortality nor morbidity. Five patients had excellent clinical outcome, two good outcome, one fair and three poor. Two patients died of unrelated causes 2 months after surgery. Radiographs showed stable bone union in four patients and stable fibrous union in five patients.

Conclusions

Given the results in this short series, we suggest that anterior screw fixation of Type IIB OF may be offered as primary treatment in octogenarians.

Keywords: Cervical spine, Odontoid, Fracture, Surgery, Octogenarians

Introduction

Upper cervical spine injuries are common in the elderly, accounting for more than 50% of all cervical spine fractures in this population [17, 19]. In patients over 80 years of age, odontoid fractures (OF) form the majority of spinal fractures at the cervical level [23]. OF are most often caused by ground-level falls because of the fragility of cortical and cancellous portions of the dens with age. The specifics of type IIB OF anatomy (oblique downward and backward fracture line) make these fractures unstable and life threatening [6, 19, 23].

In spite of the relative frequency of OF in the elderly, there is a lack of agreement regarding the optimal management of these fractures with no published standards or guidelines to date [19]. In most studies, no distinction of age is made among elderly patients and definition of “elderly” is variable. To the best of our knowledge, only one study [22] takes an interest in treatment of type II OF in the specific population of octogenarians but none examines only IIB OF. Several management options are described in the literature: rigid and non-rigid immobilisations, anterior screw fixation of the odontoid and posterior fusion of the C1/C2 complex [19]. Authors advocating surgical treatment criticize the morbidity associated with prolonged cervical immobilisation [15] whereas authors advocating orthopaedic treatment invoke the risks of surgical intervention [2, 11]. The initial surgical treatment by posterior fusion of the C1/C2 complex provides the highest fusion rates [2, 8]. However, this procedure requires bone grafting, eliminates C1/C2 rotary motion, deteriorates the posterior soft tissue of the neck and includes the risk of vertebral artery injury. Anterior screw fixation of OF also ensures high fusion rates and preserves the C1/C2 rotary motion with a shorter operative time and a shorter hospital stay [3, 5, 16].

The aim of this study was to assess the clinical and radiological outcome of surgically treated Type IIB OF by anterior screw fixation in octogenarians.

Materials and methods

Thirty-nine elderly patients (65 years or older) were admitted to our institution for OF between 1999 and 2010. Among them, 18 patients were octogenarians. Twelve octogenarian patients had a type IIB OF. Other six patients had a type III OF (3 cases), a type IIA OF (2) and a type IIC OF (1). Among the 12 patients with type IIB OF, general health conditions were graded according to the scheme devised by the American Society of Anesthesiology (ASA): 5 patients were defined as class II (having mild systemic disease but no functional limitation), 6 as class III (having severe systemic disease and definite functional limitations) and 1 patient had contra-indications to general anaesthesia (ASA IV). These 11 patients with type II OF were treated by anterior screw fixation and their medical records analysed. The mean age of the patients (7 women and 4 men) was 85.4 years at the time of operation. The majority of the injuries were caused by minor falls, and the main symptom was cervical pain. The preoperative status of the patients was graded using the American Spinal Injury Association (ASIA) impairment scale: all the patients rated E (Normal: motor and sensory functions). The diagnosis was established radiographically, including standard antero-posterior, lateral and open-mouth radiographs and cervical computed tomography (CT) scans. OFs were classified according to the method of Anderson and D’Alonzo [1] and Grauer [9]. A combination of C1/C2 fractures was noted in three patients. These associated fractures were stable and did not call for external immobilisation. Posterior displacement greater than 2 mm on initial radiographs was noted in five patients. The mean duration of interval between time of traumatism and time of surgery was 11.5 days (range 2–30 days).

Follow-up assessment included operative mortality and morbidity rates, long-term functional outcome and fracture union and stability. Long-term functional outcome was assessed using a modification of the Smiley–Webster Scale [21] (Table 1). Fracture union and stability were determined by cervical CT scan, or by standard cervical radiographs when a CT scan was not available. Bone union was defined by evidence of bone trabeculae crossing the fracture site, and absence of sclerotic borders adjacent to the fracture site (Fig. 1). Fracture stability was indicated by the absence of secondary displacement. Fibrous union was defined if there was an absence of bone union but absence of secondary displacement (Fig. 2).

Table 1.

Functional outcome scale (modification of the Smiley–Webster Scale) [21]

| Score | Functional level | Functional ability |

|---|---|---|

| I | Excellent | No pain, no noticeable change in range of movement, return to full premorbid activities, neurologically intact |

| II | Good | Occasional pain, noticeably decreased range of movement, any change from premorbid activity, neurologically intact |

| III | Fair | Moderate pain, changes in range of movement, which adversely affect daily activities or any isolated neurological event |

| IV | Poor | Significant pain, incapacity, catastrophic neurological event or death |

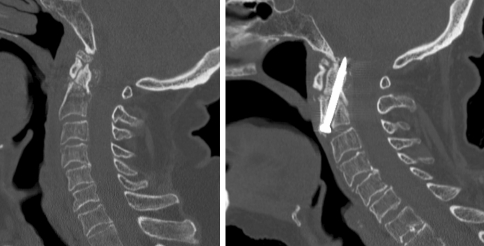

Fig. 1.

Preoperative (left) and 3 months postoperatively (right) sagittal CT scan reconstruction of type II B odontoid fracture surgically treated with anterior screw fixation: bone union stable

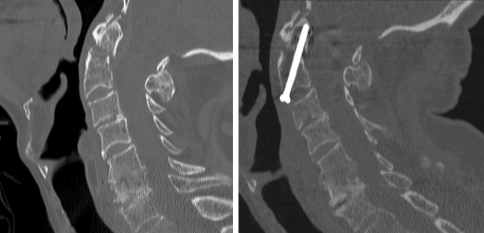

Fig. 2.

Preoperative (left) and 3 months postoperatively (right) sagittal CT scan reconstruction of type II B odontoid fracture surgically treated with anterior screw fixation: fibrous union stable

Results

All the operations were performed using lateral and antero-posterior fluoroscopic guidance. Cervical traction was used and a right unilateral horizontal incision was made along a natural skin crease, crossing the anterior border of the sternomastoid at the C5–C6 level. Fixation with one screw was carried out. Average duration of surgery was 68 min (range 30–155 min). We recorded no technical complications during surgery. No anaesthesiological or perioperative complications occurred. None of the patients had external immobilisation after surgery, even those with C1-associated fractures. Clinical results are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Eleven patients who underwent anterior screw fixation in their ninth or tenth decade of life for Type II odontoid fracture

| Case No. | Age (yr) | Sex (M/F) | Associated injuries | ASA | Time trauma/surgery (d) | Operative time (min) | Operative morbidity–mortality | Follow-up period in 2010 (mo) | Smiley-Webster Scale Postop | Union and stability | Time of union and stability (mo) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 85 | M | – | III | 13 | 66 | – | 4 | I | Bone union stable | 3 |

| 2 | 82 | F | – | III | 12 | 55 | – | 9 | I | Bone union stable | 3 |

| 3 | 86 | F | – | II | 2 | 41 | – | 14 | I | Fibrous union stable | 6 |

| 4 | 86 | F | – | II | 6 | 30 | – | 50 | II | Fibrous union stable | 8 |

| 5 | 88 | M | – | II | 14 | 55 | – | 116 | I | Bone union stable | 3 |

| 6 | 85 | F | – | II | 10 | 155 | – | 36 | III | Bone union stable | 3 |

| 7 | 85 | F | Lateral mass of C1 | II | 12 | 45 | – | 23 | II | Fibrous union stable | 9 |

| 8 | 93 | F | Posterior arch of C1 | III | 15 | 80 | – | 2 | IV | NA | NA |

| 9 | 82 | M | Anterior and posterior arch of C1 | III | 30 | 77 | – | 35 | I | Fibrous union stable | 6 |

| 10 | 83 | M | – | III | 10 | 30 | – | 2 | IV | NA | NA |

| 11 | 85 | F | – | III | 3 | 110 | – | 17 | IV | Fibrous union stable | 6 |

No. numero, yr year, M male, F female, d day, min minute, mo month, NA not available (patients died at 2 months after surgery)

There was no operative mortality and morbidity.

Nine patients attended postoperative review 2 months after operation and follow-up lasted between 4 and 116 months, with a mean of 34 months. In December 2010, all these nine patients were still alive.

After the entire follow-up period, the modified Smiley–Webster functional scale revealed that five patients had excellent outcome, two patients had good outcome, one patient had fair outcome and three patients had poor outcome at their final follow-up visit. Among the three patients with poor outcome, two patients died of unrelated causes 2 months after surgery. A total of nine patients had radiographs available at 3 months from which fusion status could be assessed. These revealed stable bone union in four patients and stable bone non-union (fibrous union) in five patients. In the case of stable bone non-union, we did not perform posterior fixation.

Discussion

Through study of a short series of 11 patients, we showed that an anterior screw fixation of Type IIB OF in octogenarians can be offered as primary treatment for this specific population. The good clinical outcome and stability on radiographs for most of the population demonstrated the effectiveness of this surgery.

With the increase in lifespan in industrial nations, the number of octogenarians with upper cervical injury is rising. Type IIB OF is the most frequent upper cervical injury in this population [19]. There is no simple answer to the question “Should OF surgery be performed on octogenarians?” This work is a contribution towards an answer to this question, and to the best of our knowledge, our study is the first concerning only an octogenarian population with type IIB OF. Optimal treatment for type II OF remains controversial in the literature [17, 19, 23] although primary surgical treatment is an increasing tendency, especially for elderly patients [13, 17].

This study focused on this specific population for three main reasons. First of all, until the 2000s, it was uncommon to perform OF surgical procedures on octogenarians, because of the theoretical fear that an elderly person would be unable to withstand general anaesthesia, the fear of multi-systemic disease and an incomplete appreciation of the life expectancy of people after the age of 80. During the last decade, the number of octogenarians having surgery has rapidly increased, with acceptable mortality and morbidity rates [23]. Thus, surgery in the octogenarian must take into account a number of factors, such as lack of synchronism between physiological age and chronological age, quality of life, risk/benefit ratio and increase in health care costs, an element that is gaining more and more importance [7, 19, 23, 25]. The issue has been settled for other surgical pathologies such as hip fractures [10] or cardiac valve replacement [12]. Secondly, more and more people aged over 80, at greater risk of ground-level falls, have upper cervical spine injuries [19]. These conditions associated with better access to CT scans have increased the incidence of OF in this age range. Only one study [22] has examined treatment of type II OF in the specific population of octogenarians using a larger population than the one we are reporting on. However, this study included conservative and surgical treatment and focused only on presentation and complications of type II OF. Among the different surgical treatments, only ten patients were treated by anterior screw fixation. In this study, the morbidity rate was 62% without distinction between surgical procedures. The other studies did not distinguish octogenarians from other elderly patients [3, 5, 7, 8, 11, 13, 15, 18, 24, 25].

We specifically studied type IIB OF because among all types of OF they are considered as the most unstable. OF displacement follows the direction of the fracture. Furthermore, displacement depends on the associated ligamentum injuries. Posterior displacements of type IIB OF threaten the spinal cord with severe neurological deterioration or even death. We chose anterior screw fixation as surgical treatment for type IIB OF in elderly patients for the following reasons. Rigid and non-rigid external immobilisations have a high mortality and morbidity rates [15, 24]. Moreover, conservative treatment could lead to the development of delayed myelopathy in patients with non-union of the OF [4]. Posterior fusion of the C1/C2 complex is superior to external immobilisation in terms of radiological outcome and morbidity and mortality [2, 8] and produces the highest fusion rates among the different types of surgical fixation [19]. Nonetheless, this surgical approach deteriorates posterior soft tissue, blocks C1/C2 axial rotation, carries the risk of vertebral artery injury of the neck and requires bone grafting. In our opinion, anterior screw fixation is the surgical procedure of choice for treatment of Type IIB OF in elderly populations. Indeed this procedure preserves normal C1/C2 rotary motion and offers immediate spinal stability and rapid patient mobilisation with a high fusion rate [3, 5, 16]. Octogenarians with type III or IIC OF were not considered for surgery because these fractures are relatively stable and not life threatening. We evaluated the policy of our team concerning management of type IIB OF in octogenarians. The assessment was carried out without a control group.

Mortality and morbidity rates reported in our series were nil while mortality and morbidity rates reported in the literature after odontoid fracture surgery in the elderly population reached 10% [25]. In particular, Smith et al. [22] reported a mortality rate of 12.5% in a specific population of octogenarians undergoing surgical treatment. No significant difference exists between anterior and posterior surgery concerning morbidity and mortality [25]. General health seems to affect clinical follow up. Indeed, two of our patients died at 2-month follow-up. Although the causes of death were independent of the surgical procedure, these two patients were graded as ASA III. On the other hand, three patients graded as ASA III showed favourable evolution during the entire follow-up period.

Although some authors advocate external immobilisation as the treatment of choice for type II OF in an elderly population [7, 11, 20], high fusion rate and best clinical outcome are obtained by surgical treatment [5, 8, 13, 14, 17–19]. Bone fusion rate in our series (44%) was lower than bone fusion rate described in the literature [17, 19] which ranged from 80 to 100%. However, stability rate was consistent with rates described in the literature [17, 19]. Moreover, a stable fibrous non-union in octogenarians seems acceptable in terms of functional outcome.

Conclusions

Until the 2000s, it was uncommon to perform OF surgical procedures on octogenarians. Although the number of patients in our study is too low to lead to any firm conclusion, we suggest that anterior screw fixation should be offered as primary treatment in octogenarians with type IIB OF. Providing recommendations for anaesthesia in elderly patients are followed, this surgical treatment can improve their quality and duration of life. Further multicenter studies with larger numbers of patients are needed to establish a complete definition of the most effective management strategy for type IIB OF in octogenarians.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Anderson LD, D’Alonzo RT. Fractures of the odontoid process of the axis. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 1974;56:1663–1674. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Andersson S, Rodrigues M, Olerud C. Odontoid fractures: high complication rate associated with anterior screw fixation in the elderly. Eur Spine J. 2000;9:56–59. doi: 10.1007/s005860050009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Börm W, Kast E, Richter HP, et al. Anterior screw fixation in type II odontoid fractures: is there a difference in outcome between age groups? Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1089–1092. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000057697.62046.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crockard HA, Heilman AE, Stevens JM. Progressive myelopathy secondary to odontoid fractures: clinical, radiological, and surgical features. J Neurosurg. 1993;78:579–586. doi: 10.3171/jns.1993.78.4.0579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dailey AT, Hart D, Finn MA, et al. Anterior fixation of odontoid fractures in an elderly population. J Neurosurg Spine. 2010;12:1–8. doi: 10.3171/2009.7.SPINE08589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dunn ME, Seljeskog EL. Experience in the management of odontoid process injuries: an analysis of 128 cases. Neurosurgery. 1986;18:306–310. doi: 10.1227/00006123-198603000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fagin AM, Cipolle MD, Barraco RD, et al. Odontoid fractures in the elderly: should we operate? J Trauma. 2010;68:583–586. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3181b23608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frangen TM, Zilkens C, Muhr G, et al. Odontoid fractures in the elderly: dorsal C1/C2 fusion is superior to halo-vest immobilization. J Trauma. 2007;63:83–89. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318060d2b9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grauer JN, Shafi B, Hilibrand AS, et al. Proposal of a modified, treatment-oriented classification of odontoid fractures. Spine J. 2005;5:123–129. doi: 10.1016/j.spinee.2004.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hopley C, Stengel D, Ekkernkamp A, et al. Primary total hip arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty for displaced intracapsular hip fractures in older patients: systematic review. BMJ. 2010;340:c2332. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c2332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Koech F, Ackland HM, Varma DK, et al. Nonoperative management of type II odontoid fractures in the elderly. Spine. 2008;33:2881–2886. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e31818d5407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kolh P, Kerzmann A, Lahaye L, et al. Cardiac surgery in octogenarians. Peri-operative outcome and long-term results. Eur Heart J. 2001;22:1235–1243. doi: 10.1053/euhj.2000.2443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kuntz C, IV, Mirza SK, Jarell AD, et al. Type II odontoid fractures in the elderly: early failure of nonsurgical treatment. Neurosurg Focus. 2000;8:e7. doi: 10.3171/foc.2000.8.6.8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lennarson PJ, Mostafavi H, Traynelis VC, et al. Management of type II dens fractures: a case-control study. Spine. 2000;25:1234–1237. doi: 10.1097/00007632-200005150-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Majercik S, Tashjian RZ, Biffl WL, et al. Halo vest immobilization in the elderly: a death sentence? J Trauma. 2005;59:350–357. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000174671.07664.7c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Morandi X, Hanna A, Hamlat A, et al. Anterior screw fixation of odontoid fractures. Surg Neurol. 1999;51:236–240. doi: 10.1016/S0090-3019(98)00113-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nourbakhsh A, Shi R, Vannemreddy P, et al. Operative versus nonoperative management of acute odontoid type II fractures: a meta-analysis. J Neurosurg Spine. 2009;11:651–658. doi: 10.3171/2009.7.SPINE0991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Omeis I, Duggal N, Rubano J, et al. Surgical treatment of C2 fractures in the elderly: a multicenter retrospective analysis. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2009;22:91–95. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e3181723d1b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pal D, Sell P, Grevitt M. Type II odontoid fractures in the elderly: an evidence-based narrative review of management. Eur Spine J. 2011;20:195–204. doi: 10.1007/s00586-010-1507-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Platzer P, Thalhammer G, Sarahrudi K, et al. Nonoperative management of odontoid fractures using a halothoracic vest. Neurosurgery. 2007;61:522–530. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000290898.15567.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seybold EA, Bayley JC. Functional outcome of surgically and conservatively managed dens fractures. Spine. 1998;23:1837–1846. doi: 10.1097/00007632-199809010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith HE, Kerr SM, Maltenfort M, et al. Early complications of surgical versus conservative treatment of isolated type II odontoid fractures in octogenarians: a retrospective cohort study. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2008;21:535–539. doi: 10.1097/BSD.0b013e318163570b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Smith HE, Vaccaro AR, Maltenfort M, et al. Trends in surgical management for type II odontoid fracture: 20 years of experience at a regional spinal cord injury center. Orthopedics. 2008;31:650. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tashjian RZ, Majercik S, Biffl WL, et al. Halo-vest immobilization increases early morbidity and mortality in elderly odontoid fractures. J Trauma. 2006;60:199–203. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000197426.72261.17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.White AP, Hashimoto R, Norvell DC, et al. Morbidity and mortality related to odontoid fracture surgery in the elderly population. Spine. 2010;35:S146–S157. doi: 10.1097/BRS.0b013e3181d830a4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]