Abstract

Mutation of the tumor suppressor adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) is considered an initiating step in the genesis of the vast majority of colorectal cancers. APC inhibits the Wnt signaling pathway by targeting proto-oncogene β-catenin for destruction by cytoplasmic proteasomes. In the presence of a Wnt signal, or in the absence of functional APC, β-catenin can serve as a transcription co-factor for genes required for cell proliferation such as cyclin D1 and c-Myc. In cultured cells, APC shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm, with nuclear APC implicated in inhibition of Wnt target gene expression. Taking a genetic approach to evaluate the functions of nuclear APC in the context of a whole organism, we generated a mouse model with mutations that inactivate the nuclear localization signals of Apc (ApcmNLS). ApcmNLS/mNLS mice are viable and fractionation of embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) isolated from these mice revealed a significant reduction in nuclear Apc compared to Apc+/+ MEFs. The levels of Apc and β-catenin protein were not significantly altered in small intestinal epithelia from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice. Compared to Apc+/+ mice, ApcmNLS/mNLS mice displayed increased proliferation in epithelial cells from the jejunum, ileum, and colon. These same tissues from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice displayed more mRNA from three genes up-regulated in response to canonical Wnt signal, c-Myc, Axin2, and Cyclin D1, and less mRNA from Hath 1 which is down-regulated in response to Wnt. These observations suggest a role for nuclear Apc in inhibition of canonical Wnt signaling and control of epithelial proliferation in intestinal tissue. Furthermore, we found ApcMin/+ mice, which harbor a mutation that truncates Apc, have increased polyp size and multiplicity if they also carry the ApcmNLS allele. Taken together, this analysis of the novel ApcmNLS mouse model supports a role for nuclear Apc in control of Wnt target genes, intestinal epithelial cell proliferation and polyp formation.

Introduction

The tumor suppressor protein adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) is large, with multiple subcellular localizations and functions. Mutation of the APC gene is considered the initiating event in the formation of most intestinal polyps, the precursors to colorectal cancer (21, 22, 44). As such, an intense investigation of potential APC functions involved in tumor suppression has led to identification of APC as a Wnt signaling pathway antagonist (10). In this capacity, APC is part of a cytoplasmic protein complex that targets the proto-oncoprotein β-catenin for proteasome-mediated destruction (25). APC has also been observed in nuclei of cultured colon cells and colonic epithelia from human tissue using conventional and confocal immunofluorescent microscopy and immunoelectron microscopy (1, 31, 42). Nuclear APC has three proposed roles in regulating Wnt signaling. First, nuclear APC binds to nuclear β-catenin and likely competes with transcription factor TCF/LEF for β-catenin binding (32). Second, nuclear APC has been implicated in the nuclear export of β-catenin (13, 33, 39). Finally, the interaction of nuclear APC with transcriptional corepressor CtBP further contributes to the modulation of Wnt signaling (43). In addition to its role as a repressor of β-catenin, nuclear APC has been implicated in DNA synthesis and repair (15, 37).

Because APC is a large protein (~310 kDa), it is unable to simply diffuse into the nucleus but must instead be actively transported through nuclear pores (20, 35). Several domains of APC have been proposed to mediate this nuclear entry, including two monopartite nuclear localization signals (NLS) in the central part of the protein (51), as well as an armadillo repeat region closer to the N-terminus (9). In addition, phosphorylation of APC regulates its localization (51) and relative levels of nuclear and cytoplasmic APC appear to correlate with the proliferative status of a cell (52).

Although many mouse models have been generated with alterations in Apc, they either produce no Apc protein (3), full-length Apc at a reduced level (14), or a truncated Apc (4, 7, 16, 24, 34, 41, 45). Elimination of the C-terminal portion of Apc leads to at least partial loss of function and mice homozygous for mutations that truncate Apc typically do not develop beyond embryonic day 8 (46). To date, no mouse model with targeted disruption of the two Apc NLSs has been generated.

To assess the functions of nuclear Apc in the context of a whole organism, we introduced germline mutations into the mouse Apc gene that result in inactivation of the two characterized Apc NLSs (ApcmNLS). Inactivation of the two APC NLSs was previously shown to attenuate the ability of full-length exogenous human APC to enter the nucleus (51). In the present study, mice heterozygous (ApcmNLS/+)or homozygous (ApcmNLS/mNLS) for mutant Apc NLS were viable. Intestinal epithelial cells in ApcmNLS/mNLS mice showed increased levels of Wnt target gene expression and more proliferation compared to their wild-type littermates. For the past two decades, the ApcMin/+ mouse has been a popular model organism to study Apc mutation-driven tumorigenesis (23). ApcMin/+ mice have a missense mutation in Apc that results in truncation of the C-terminal 2/3 of the protein. ApcMin/+ mice develop 20–60 intestinal polyps at the time of their natural death, ~120 days of age. We found that ApcMin/mNLS mice displayed significantly more intestinal polyps than ApcMin/+ mice and these polyps were larger. Together, these results suggest that nuclear Apc participates in regulation of Wnt signaling, proliferation and tumor suppression.

Results

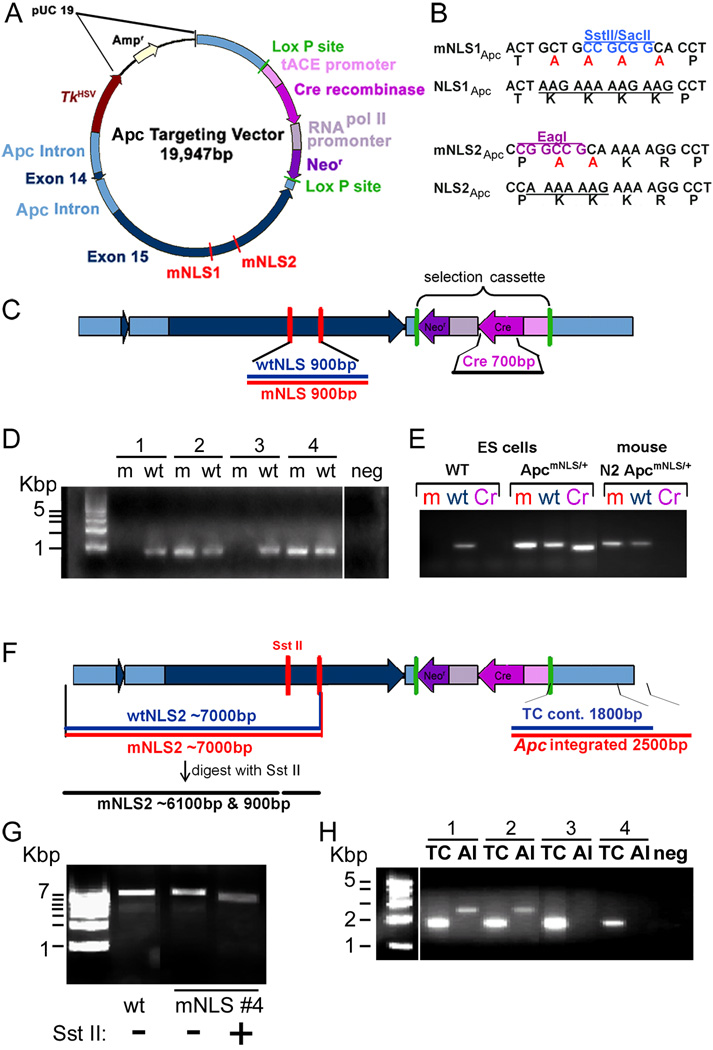

Mutation of two Apc NLSs in ES cells and generation of mutant mice

To introduce specific mutations that inactivate both Apc NLSs in mouse embryonic stem (ES) cells and ultimately generate ApcmNLS/mNLS mice, we constructed a gene-targeting vector (Figure 1A). The targeted mutations alter a total of six amino acids in Apc, four in NLS1 and two in NLS2 (Figure 1B). These mutations substitute a neutral alanine for the basic lysine residues in the mono-partite NLSs and have been shown to inhibit nuclear import of exogenously expressed APC (51). Each NLS is adjacent to a SAMP repeat region (so named because they each contain a central Ser-Ala-Met-Pro) which is involved in APC binding to axin. However, mutation of both NLSs does not appear to interfere with axin binding as full-length APC with mutations in both NLSs still interacts with axin (Supplemental Fig. 1). These mutations also establish two novel restriction sites, Sst II in NLS1 and Eag I in NLS2 which were utilized for screening purposes (Figure 1B). The targeting vector contains an 11.5 kb genomic Nhe I/ Not I fragment encompassing exons 14 and 15 of Apc as well as the surrounding introns. The entire Apc region of the vector was validated by sequencing. The positive selection marker contained in a germline-induced self-excision cassette was placed in the intron following Apc exon 15 (2). In mice, the tACE promoter initiates transcription of Cre-recombinase during spermatogenesis, inducing Cre-mediated self-excision of the selectable Neor marker in the germline of the transgenic animals. Following self-excision, only one 34 bp minimal LoxP element remains in the last Apc intron. The targeting construct also contains a copy of the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene (TkHSV) to allow negative selection of homologous recombinant ES clones.

Figure 1. Generation of ApcmNLS/+ mouse ES cell lines.

(A) Schematic representation of Apc NLS targeting vector. Drawn roughly to scale, the vector includes Apc exons 14 and 15 (dark blue), with surrounding introns (light blue). A Neomycin resistance gene (Neor, purple) inserted in the final Apc intron is flanked by Lox P sites (green) that will facilitate its excision when expressed in the testes where the tACE promoter (murine angiotensin-converting enzyme) drives expression of Cre recombinase. The herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase gene (TkHSV) allows negative selection of homologous recombinant ES cell clones. (B) Mutations in Apc NLS1 and NLS2 result in amino acid substitutions inactivating the nuclear localization signals and also introduce unique restriction enzyme sites for screening purposes. (C) Analysis of ES cell lines with PCR using primers specific for the wildtype (wt) or mutant (m) Apc NLS allowed identification of 107 lines with both Apc NLS1 and NLS2 mutated. (D) Samples 2 and 4 in the gel image shown each have both Apc NLSs mutated. PCR reaction without template DNA (neg). (E) Excision of the Ace-Cre-Neor selection cassette was verified in N2 ApcmNLS/+ mice using PCR with primers specific for Cre. Genomic DNA isolated from wild type (WT) and ApcmNLS/+ ES cell lines was used as a negative and positive control, respectively, for the Cre primer PCR (Cr). PCR using primers specific for wild type sequence (wt) and mutant sequence (m) confirmed that the mouse analyzed was ApcmNLS/+ and demonstrated genomic DNA quality sufficient for PCR analysis. (F) Scheme to determine correct integration of the 5’ and 3’ ends of the targeting vector. (G) Correct integration of the 5’ end of the targeting vector was established by PCR analysis using a primer specific for mutant Apc NLS2 with a second primer that recognizes genomic sequence outside the targeting construct and upstream of a correctly integrated vector. Products of this PCR reaction were digested with Sst II to confirm integration of mutant Apc NLS1. (H) PCR analysis using a primer unique to the targeting construct with a second primer that recognizes genomic sequence outside the targeting construct and downstream of a properly integrated vector allowed identification of 8 recombinant ES cell lines that had correctly integrated the 3’ end of the targeting vector (samples 1 and 2). TC, targeting vector control product is ~ 1800 bp if targeting vector is integrated into genomic DNA. AI, Apc integrated product is ~ 2500 bp if targeting vector is properly inserted into the Apc gene.

Identification of homologous recombinant ES clones was accomplished using PCR with different primer pairs inside and outside the targeting construct. Of the 161 ES cell clones that survived positive and negative selection, 107 contained Apc with both mutant NLSs (Fig. 1C, 1D). Eight of these ES cell clones were identified as homologous recombinants by PCR to verify correct insertion of the 3’ region of the vector (Fig. 1F, 1H). Two were further analyzed by PCR and then subjected to restriction digestion in order to verify correct insertion of the 5’ region of the vector and to confirm that both mutant NLSs were integrated (Fig. 1F, 1G). One ES line with normal karyotype in 75% of the 50 cells analyzed was used for the initial blastocyst injections. From these injections, 11 chimeric mice, 4 females and 7 males, were obtained; 3 males showed evidence of germline transmission when bred with wild-type C57BL/6J mice.

Elimination of the Neor/Cre selection cassette in ApcmNLS/+ mice

In the Apc1638N mouse model, a Neor selection gene inserted in exon 15 of Apc resulted in a dramatic decrease in the expression of the mutant Apc (7, 18). Thus it was critical to ensure that the Neor gene was excised from the ApcmNLS/+ mice. Excision of the Neor cassette in animals was verified by PCR analysis using oligos within the Neor/Cre selection cassette to prime DNA amplification of genomic DNA isolated from ApcmNLS/+ mice in the N1 and N2 generations (Figure 1E).

ApcmNLS/mNLS mice are viable

Many of the previously generated Apc mouse models display early embryonic lethality as homozygous mutants. When ApcmNLS/+ mice were interbred, both ApcmNLS/+ and ApcmNLS/mNLS mice were obtained. Thus, the two characterized monopartite nuclear localization signals of Apc are not essential for viability. ApcmNLS/mNLS mice showed no obvious growth defects compared to their wild-type littermates in generations N1-N13. ApcmNLS/mNLS mice are fertile, giving birth to litters of typical size. A long term survival analysis of 55 progeny from first generation ApcmNLS/+ females bred to first generation ApcmNLS/+ males revealed no significant difference in mouse survival between ApcmNLS/mNLS and Apc+/+ mice (data not shown). Thus, it appears that mutation of Apc NLS sequence has limited impact on the lifespan of the mice.

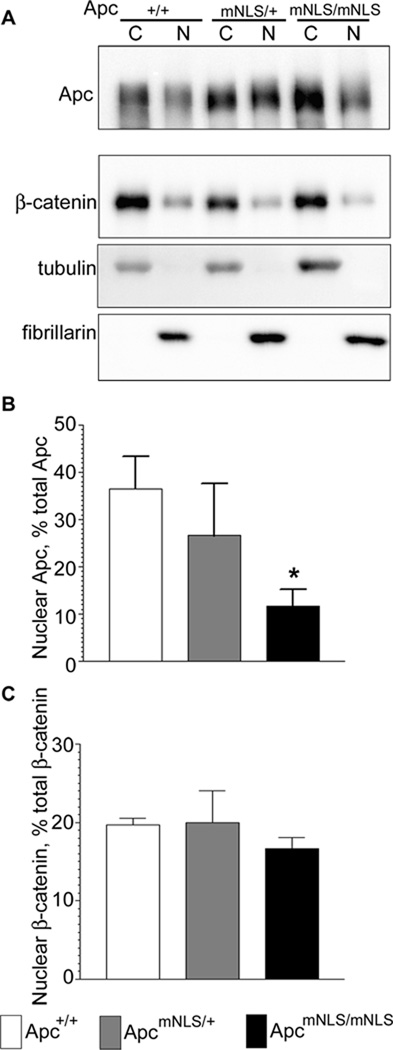

Reduced nuclear Apc in embryonic fibroblasts isolated from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice

Because of complications associated with fractionation of cells obtained from intestinal tissue, we used mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) isolated from congenic (generation N11) mice to determine effects of ApcmNLS on subcellular Apc localization (Fig. 2A). In Apc+/+ MEFs, more than one-third of the total Apc was associated with the nuclear fraction (Fig. 2B). ApcmNLS/mNLS MEFs were significantly compromised for nuclear Apc distribution, with eleven percent of the total Apc associated with the nuclear fraction. ApcmNLS/+ MEFs showed an intermediate phenotype, but nuclear Apc was not significantly different from that in Apc+/+ MEFs. β-catenin distribution was similar in all MEF lines (Fig. 2C). Moreover, β-catenin appeared predominantly at cell-cell junctions in intestinal tissue from Apc+/+, ApcmNLS/+ and ApcmNLS/mNLS mice as assessed by immunohistochemistry (Supplemental Fig. 2A). A few crypts showed limited nuclear β-catenin staining in cells near their base, but this was consistent for all mouse genotypes (Supplemental Fig. 2B).

Figure 2. Reduced nuclear Apc levels in MEFs from ApcmNLS/+ and ApcmNLS/mNLS mice.

(A) Mouse Embryonic Fibroblasts (MEFs) isolated from congenic Apc+/+, ApcmNLS/+ and ApcmNLS/mNLS mice were subjected to fractionation followed by immunoblot. A single blot, probed for Apc, β-catenin, tubulin (cytoplasmic marker) and fibrillarin (nuclear marker) is shown. (B) Apc band intensities were determined and results from five independent fractionation experiments performed on three different isolations of MEF cells are presented as the fraction of the total Apc protein in the nucleus ± SEM. ApcmNLS/mNLS MEFs displayed significantly less nuclear Apc than Apc+/+ MEFs (p = 0.012). (C) β-catenin distribution, determined as in (B), was similar in all MEF lines.

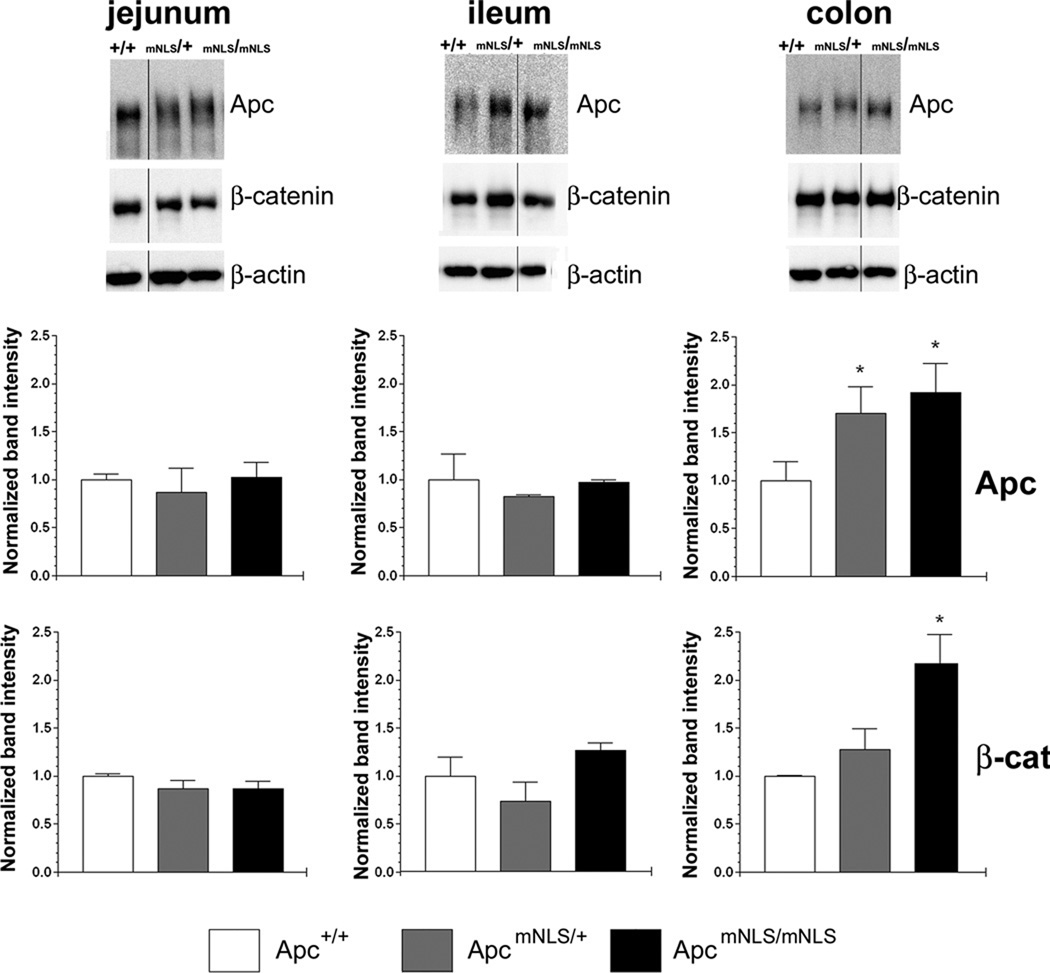

Apc and β-catenin levels in intestinal tissue

To determine if the single Lox P site remaining in the last Apc intron impacts Apc level in ApcmNLS mice, we measured the relative amount of Apc in whole cell protein lysates prepared from epithelial cells isolated from mouse jejunum, ileum and colon (Fig. 3). The Apc level did not vary significantly in epithelia from jejunum or ileum tissue isolated from ApcmNLS/mNLS, ApcmNLS/+ and Apc+/+ mice. Unexpectedly, colon epithelia from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice had higher levels of Apc than colon epithelia from Apc+/+ mice. Because Apc targets proto-oncoprotein β-catenin for destruction, higher Apc levels would be expected to result in reduced β-catenin levels. Unexpectedly, colon tissue from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice showed higher levels of β-catenin than colon tissue from Apc+/+ mice. In the small intestine, β-catenin levels were not altered in ApcmNLS/mNLS mice compared to Apc+/+ mice.

Figure 3. Apc and β-catenin levels in intestinal epithelia from ApcmNLS/+ and ApcmNLS/mNLS mice.

Epithelial cells were isolated from three intestinal segments (jejunum, ileum and colon) of congenic Apc+/+, ApcmNLS/+ and ApcmNLS/mNLS mice. Proteins from whole cell lysates were resolved using SDS-PAGE. Immunoblots were probed for Apc, β-catenin and β-actin which served as a loading control (top panels). Band intensities were determined for four samples from each genotype and are presented as average band intensity ± SEM relative to β-actin and normalized to the Apc+/+ sample which was set to 1 (middle and bottom panels). Apc and β-catenin levels appeared comparable in epithelial cells isolated from jejunum and ileum of mice of each genotype. Using the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test, colon tissue from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice showed significantly higher levels of both Apc (p = 0.017) and β-catenin (p = 0.01) than colon tissue from Apc+/+ mice.

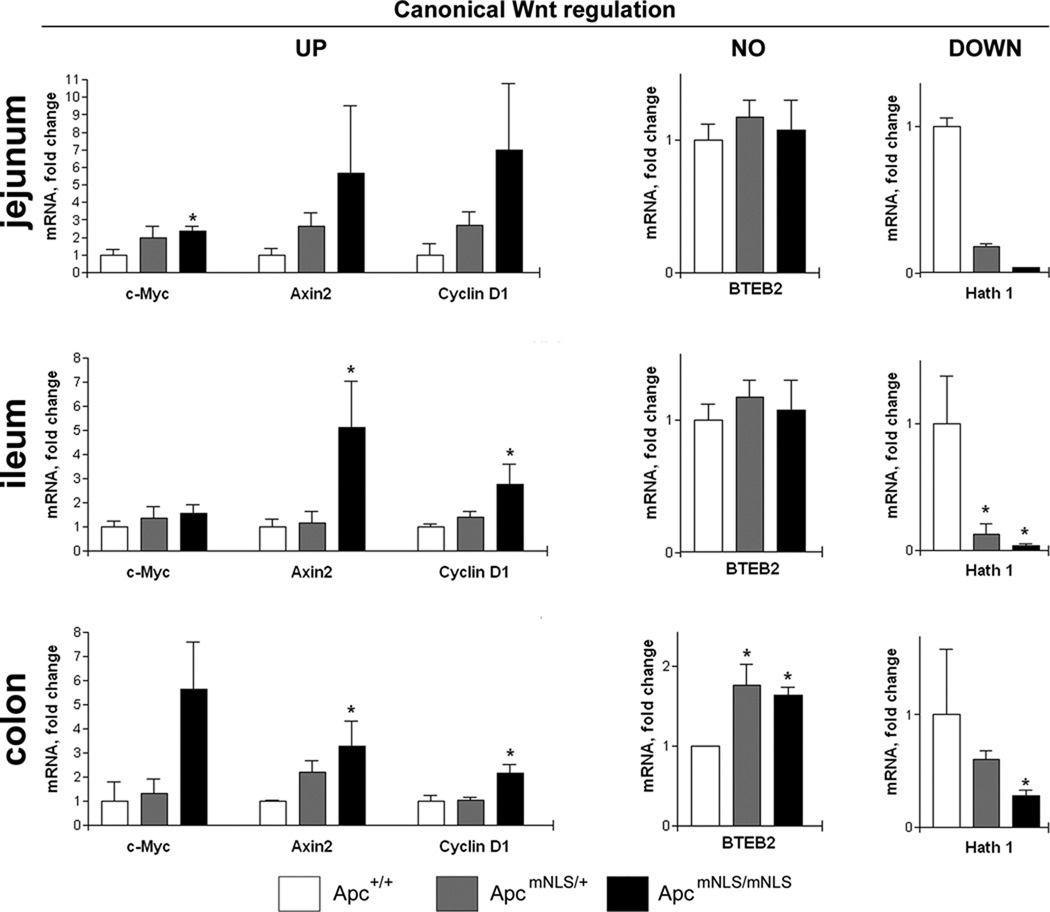

Increased expression of Wnt targets in intestinal epithelia of ApcmNLS/mNLS mice

Based on previous studies performed in cultured cells, we proposed that nuclear APC binds nuclear β-catenin and sequesters it from transcription factor TCF/LEF. Consequently, Wnt target genes activated by the β-catenin/TCF/LEF complex are down-regulated by nuclear APC (33). Thus we predicted that cells defective in nuclear Apc would be less able to dampen Wnt target gene expression. To test this prediction, mRNA isolated from intestinal epithelial cells was evaluated for relative expression of various Wnt-regulated genes (Figure 4). Three genes typically up-regulated in response to a canonical Wnt signal, c-Myc, Axin2, and Cyclin D1 showed higher expression throughout the intestinal epithelia of ApcmNLS/mNLS mice compared to Apc+/+ mice. In these same tissues, Hath 1, a gene down-regulated in response to a canonical Wnt signal showed lower expression throughout the intestinal epithelia of ApcmNLS/mNLS mice compared to Apc+/+ mice. BTEB2, a gene reportedly up-regulated in response to non-canonical Wnt signal, showed no expression alterations in jejunum or ileum from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice compared to Apc+/+ mice. Unexpectedly, in colon tissue, BTEB2 expression was higher in both ApcmNLS/mNLS and ApcmNLS/+ mice compared to Apc+/+ mice.

Figure 4. Elevation of Wnt target gene expression in ApcmNLS/mNLS mice.

Epithelial cells were isolated from three intestinal segments (jejunum, ileum and colon) of congenic Apc+/+, ApcmNLS/+ and ApcmNLS/mNLS mice. For each sample, mRNA levels of three genes up-regulated by canonical Wnt signaling (cMyc, Axin2, and Cyclin D1), one gene which is down-regulated by canonical Wnt signaling (Hath1), and one gene which is not regulated by canonical Wnt signaling (BTEB2), each normalized to HGPRT (housekeeping gene, control) were determined using real time quantitative RT-PCR. Results from 4–6 mice are presented as average mRNA level relative to that found in the Apc+/+ sample ± SEM. p values < 0.05 as calculated using the Mann-Whitney nonparametric test, are indicated with *. Levels of Hath 1 mRNA in jejunum samples from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice were around the lower limit of detection, precluding calculation of a ΔΔC(T) for some samples.

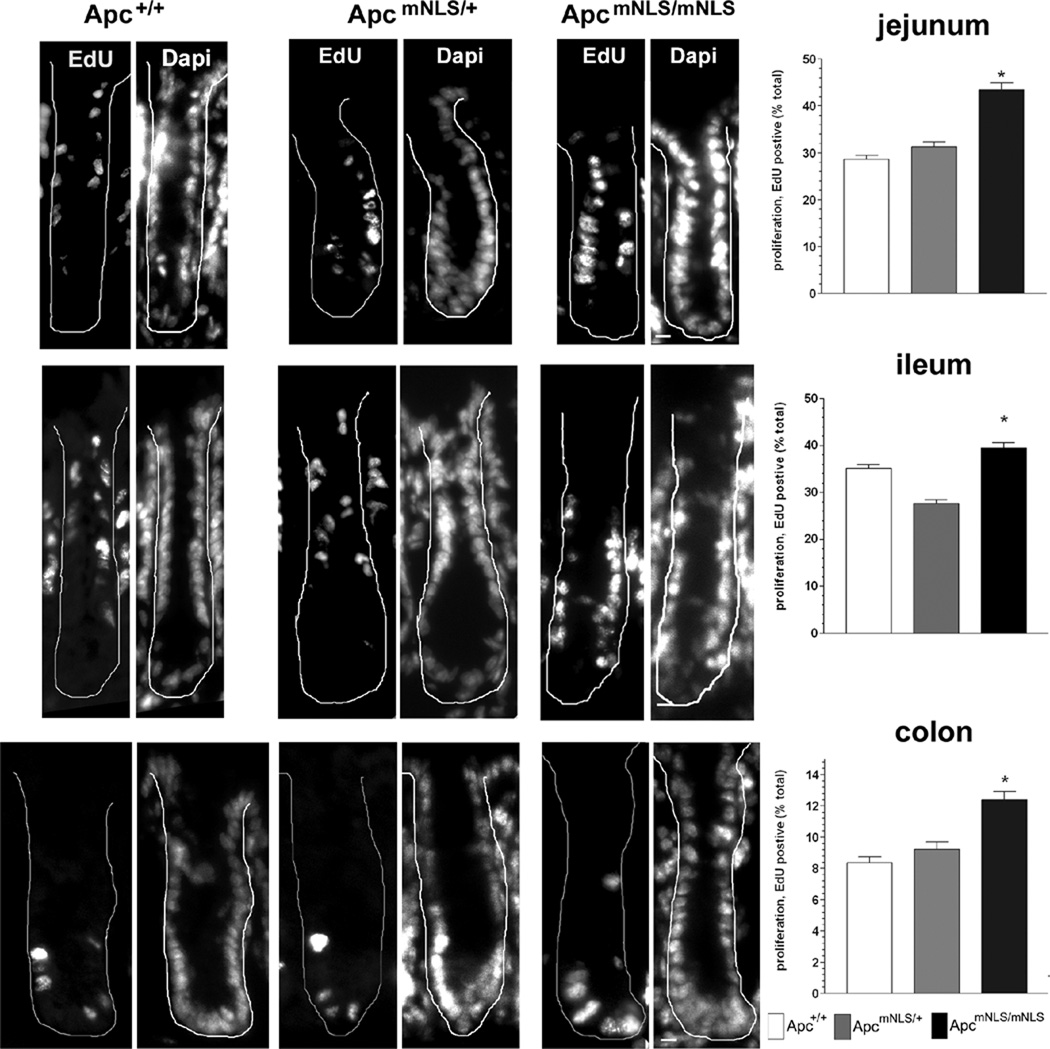

Increased proliferation in intestinal epithelia of ApcmNLS/mNLS mice

Given the increased expression of c-Myc and Cyclin D1 in intestines of ApcmNLS/mNLS mice, we expected to find an accompanying increase in proliferation. To evaluate epithelial cell proliferation in intestinal tissue, mice were analyzed 4 hours after injection with the thymidine analogue EdU. Crypts from jejunum, ileum and colon each displayed significantly more proliferating cells in ApcmNLS/mNLS mice than in ApcmNLS/+ and Apc+/+ mice (Fig. 5).

Figure 5. Increased epithelial cell proliferation in intestines of ApcmNLS/mNLS mice.

Representative images of crypts from EdU-labeled intestinal tissue isolated from Apc+/+, ApcmNLS/+ and ApcmNLS/mNLS mice with white line denoting crypt border (left panels). Dapi staining allowed identification of cell nuclei. Scale bar, 10 µm. Right panels, the average number of EdU-positive cells per crypt cross section normalized to the total crypt cell number is presented with error bars indicating SEM. Samples were collected from 3 mice of each genotype. Top, jejunum tissues showed a significant increase in proliferation in ApcmNLS/mNLS mice compared to Apc+/+ mice (p < 0.0001). Middle, ileum tissues showed a significant increase in proliferation in ApcmNLS/mNLS mice compared to Apc+/+ mice (p < 0.05). Bottom, colon tissues showed a significant increase in proliferation in ApcmNLS/mNLS mice compared to Apc+/+ mice (p < 0.0001).

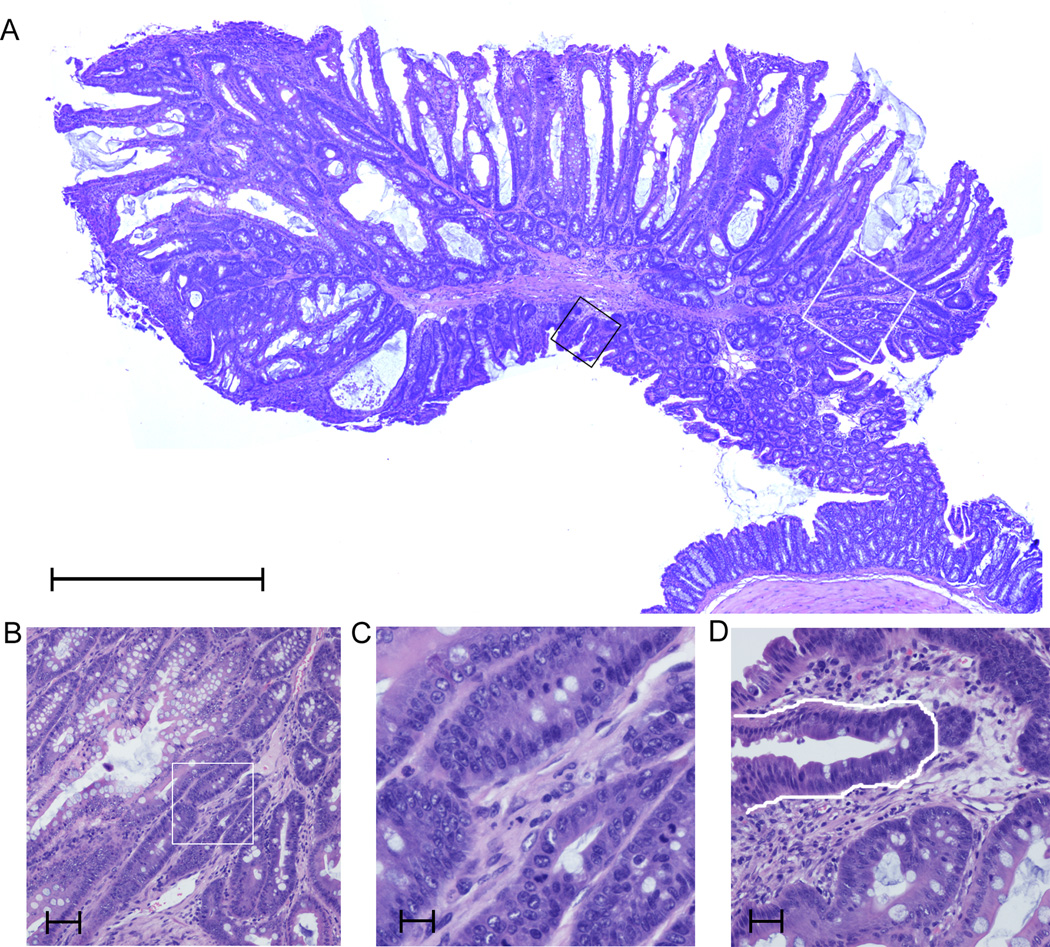

Enhanced polyp formation in intestines of ApcMin/mNLS mice

Mice with germline truncating mutations in Apc occasionally display a few adenomatous polyps in the colon, with the great majority of polyps found in the small intestine (46). Therefore, we targeted both colon and small intestine for our initial phenotypic analysis. No adenomatous polyps of the small intestine were identified in any of the ApcmNLS/+ mice from generations N1-N4 analyzed for intestinal lesions (n=33). One dysplastic colon polyp was found in an ApcmNLS/mNLS mouse (Fig. 6A–D). A polyp was also found in the stomach of another ApcmNLS/mNLS mouse (generation N11).

Figure 6. Polyps in ApcmNLS/mNLS mice.

(A) Low power magnification of lesion in colon of ApcmNLS/mNLS mouse. scale bar, 1 mm. (B) Same lesion with higher magnification of region outlined by white box in (A) showing epithelial atypia. Nuclei are enlarged with loss of polarization. scale bar, 100 µm. (C) Higher power magnification of region with cell atypia from (B) showing enlarged nuclei. scale bar, 25 µm. (D) A progression of atypia is shown in the same tissue (approximate area shown in black box in (A)) from lower right with more polarized nuclei to upper left with enlarged non-polarized nuclei. A representative dysplastic crypt is outlined in white. scale bar, 50 µm.

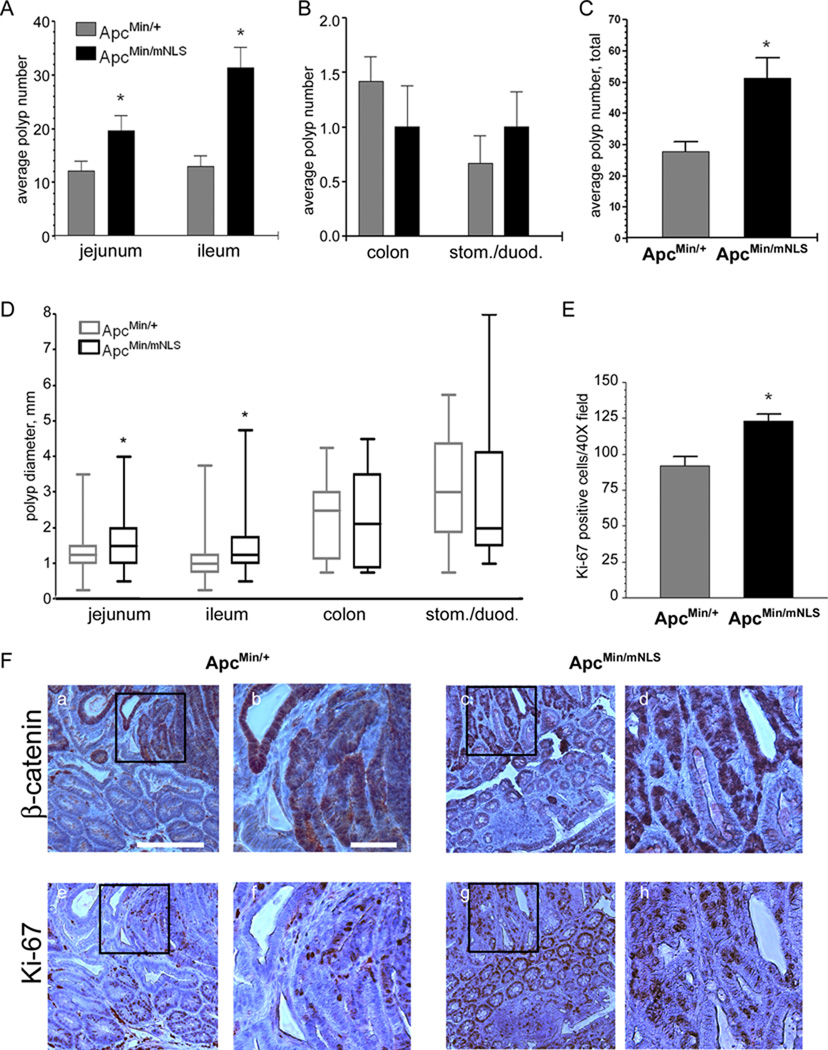

The few intestinal lesions observed in the ApcmNLS/mNLS mice left open the possibility that nuclear Apc participates in polyp suppression. To examine this more efficiently, congenic ApcmNLS/+ mice were bred with ApcMin/+ mice. Polyp number, size and distribution were compared in 14-week old progeny ApcMin/+ and ApcMin/mNLS mice. Significantly more polyps were found in the jejunum and the ileum of ApcMin/mNLS mice than in ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 7A and supplementary Fig 3). There were only a few polyps observed in any colon tissue with no significant variation between ApcMin/+ and ApcMin/mNLS mice (Fig. 7B and supplementary Fig 3). Even fewer polyps were observed in the stomach and duodenum tissues, but the average polyp number was slightly larger in ApcMin/mNLS mice than in ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 7B and supplementary Fig 3). Combining results from the entire G.I. tissue, we observed nearly twice as many polyps in ApcMin/mNLS mice than in ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 7C). These results suggest that the ApcmNLS enhances polyp initiation or development in the ApcMin mouse model. Furthermore, the average polyp size was significantly larger in jejunum and ileum tissue of ApcMin/mNLS mice compared to ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 7D). Collectively, the results from this study suggest that nuclear Apc contributes to a tumor suppressor phenotype.

Figure 7. ApcMin/mNLS mice have more and larger polyps than ApcMin/+ mice.

Polyps were identified and measured in fourteen-week old ApcMin/+ (n=12) and ApcMin/mNLS (n=8) mice. (A) Results presented as average polyp number per mouse ± SEM indicate significantly more polyps in the jejunum (p = 0.035) and the ileum (p = 0.0002) of ApcMin/mNLS mice compared to ApcMin/+ mice. (B) Polyps were also identified in the colon, stomach, and duodenum but showed no statistically significant differences in ApcMin/mNLS and ApcMin/+ mice. (C) Results from all G.I. tissues combined (jejunum, ileum, colon, stomach, duodenum) indicate significantly more polyps in ApcMin/mNLS compared to ApcMin/+ mice (p = 0.0021). (D) Diameters of all polyps are shown as a box and whisker plot. Polyps in both jejunum and ileum were significantly larger in ApcMin/mNLS mice than in ApcMin/+ mice (p < 0.0001). (E) Significantly more proliferation, as determined by Ki-67 expression, was observed in polyps isolated from the ileums of ApcMin/mNLS mice than ApcMin/+ mice (p = 0.0003). (F) A tissue section of polyp from ApcMin/+ or ApcMin/mNLS mice stained for β-catenin (a–d) with subsequent section stained for Ki-67 (e–h). Scale bar in (a) is 200 µm and also corresponds to (c), (e), and (g). Panels (b) (d) (f) and (h) show higher power magnifications of regions indicated with black boxes in the previous panels, with 50 µm scale bar shown in (b).

Increased proliferation in intestinal polyps from ApcMin/mNLS mice

To begin to explore the mechanism of enhanced polyp formation in ApcMin/mNLS mice, we examined cellular proliferation and β-catenin distribution in polyps from ApcMin/mNLS and ApcMin/+ mice. Strong nuclear β-catenin staining was observed in polyps from both ApcMin/mNLS and ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 7F, a–d). In contrast, β-catenin appeared predominantly at the cell-cell junctions of normal intestinal cells from both ApcMin/mNLS and ApcMin/+ mice. Although nuclear β-catenin was prevalent in both ApcMin/mNLS and ApcMin/+ polyps, not every cell with nuclear β-catenin was positive for proliferation marker Ki-67 (Fig. 7F, e–h). Closer examination of Ki-67-positive cells revealed that polyps from ApcMin/mNLS mice had significantly more proliferating cells than polyps from ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 7E). Combined with the observation that there were more polyps and these polyps were larger in intestines of the ApcMin/mNLS mice than in the ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 7 A–D), it is likely that contributions of nuclear Apc to regulation of cellular proliferation impacts tumor suppression in this newly developed model.

Discussion

Nuclear APC has been observed in cultured cells, in cells of various model organisms and in human tissues (29). Roles for nuclear APC in DNA repair and replication as well as Wnt signal regulation have been proposed (13, 15, 32, 37, 38, 43). However, to date, experimental manipulation of nuclear APC has been confined to cultured cells. In this report, we describe a new mouse model with mutations "knocked-in" the Apc gene which inactivate the two canonical Apc NLSs (51). To our knowledge, the ApcmNLS/mNLS model is the first mouse generated to specifically inhibit nuclear import of any protein by knock-in mutations that target and inactivate an NLS. ApcmNLS/mNLS mice were viable and displayed increased proliferation of epithelia throughout the small intestine and colon. Epithelia from jejunum, ileum, and colon also exhibited increased canonical Wnt signaling as evidenced by increased expression of genes up-regulated by canonical Wnt signal (cyclin D1, c-myc and Axin 2) and decreased expression of genes down-regulated by canonical Wnt signal (Hath 1). This increased Wnt signaling could explain the enhanced proliferation observed in these same tissues. Although only occasionally observed in ApcmNLS/mNLS mice, polyps in jejunum and ileum were significantly more abundant and larger, with increased proliferative index in ApcMin/mNLS mice compared to ApcMin/+ mice, implicating nuclear Apc in suppression of polyp formation.

The best characterized role for nuclear APC involves negative regulation of Wnt signaling (32, 43). Based on studies performed in cultured cells, it was proposed that nuclear APC binds to nuclear β-catenin, sequestering it from a complex with activated TCF/LEF (32) and mediating β-catenin export to the cytoplasm (13, 33, 39). There is also evidence that APC can interact with transcriptional corepressor CtBP (43), resulting in inhibition of TCF/LEF-mediated transcription and dampening of a Wnt signal (30). Our data indicate that Wnt signaling is up-regulated in ApcmNLS/mNLS mice, supporting a role for nuclear Apc as a negative regulator of Wnt signaling. Of note, in this study, the alterations in Wnt gene expression occurred without increased β-catenin levels. This finding supports an alternate mechanism that does not require destruction of β-catenin for Apc to elicit dampening of a Wnt signal. We also found that cells from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice had no increase in nuclear β-catenin, consistent with a role for nuclear Apc in transport of transcription repressors to the β-catenin/TCF/LEF complex and/or sequestration of nuclear β-catenin. However, as cells from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice displayed some nuclear Apc, we can not fully exclude the possibility that Apc also plays a role in nuclear export of β-catenin.

Some Wnt target genes such as c-Myc and cyclin D1 are associated with cell cycle progression (12, 47). If nuclear Apc down-regulates Wnt signaling, then reduced nuclear Apc should lead to enhanced TCF/LEF-mediated transcription, increased expression of c-Myc and cyclin D1, and consequently, more proliferation. Our finding that intestinal epithelia of ApcmNLS/mNLS mice display increased Wnt signaling, including up-regulation of c-Myc and cyclin D1, and increased proliferation further supports a role for nuclear Apc in control of cell cycle progression.

The mutations introduced into Apc were minimal, and we expected the phenotype of ApcmNLS/mNLS mice would be more subtle than that of previous Apc mouse models which express truncated Apc proteins. The combined six amino acid substitutions in Apc NLS1 and NLS2 do not appear to impact Apc binding to β-catenin or axin (supplemental Fig. 1). Apc and β-catenin levels in epithelia isolated from either jejunum or ileum were similar in ApcmNLS/mNLS and Apc+/+ mice (Fig. 3). Therefore, the alteration in expression of canonical Wnt targets seen in these tissues did not likely result from compromised β-catenin degradation and it is likely that the observed phenotypes of ApcmNLS/mNLS mice result from compromised nuclear import of Apc.

Nuclear Apc entry was severely compromised, but not entirely eliminated in MEFs from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice (Fig. 2). The two Apc NLSs that were inactivated in our mouse model are each classic monopartite NLSs, which bind to importin-α in the cytoplasm to target protein transport through the nuclear pore (5, 11). The continued presence of some Apc in the nuclei of MEFs isolated from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice supports the existence of alternative processes by which Apc may gain nuclear access. In the mouse model described here, the two canonical NLSs are eliminated, but the Armadillo repeat domain which has been previously implicated in nuclear import of APC remains intact (9). In human polyp tissue and colon cancer cell lines, the Armadillo repeat domain has been proposed to mediate nuclear entry of truncated forms of APC that lack the canonical NLSs (1, 6). Moreover, the 15-amino acid repeat region of APC (aa. 959–1338) can facilitate nuclear import of a fused green fluorescent protein (49). It is possible that one or both of these auxiliary Apc domains binds to nuclear import machinery directly, or may allow Apc binding to other proteins that are able to facilitate nuclear import or retention of Apc.

The most surprising result from this study was that ApcMin/mNLS mice had nearly twice as many polyps as ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 7C). Furthermore, polyps from ApcMin/mNLS mice were larger on average than those from ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 7D). Together, these observations are consistent with a role for nuclear Apc in suppression of polyp initiation or progression. ApcmNLS/mNLS mice showed increased proliferation and Wnt signaling, either of which would be expected to enhance polyp formation. A recent report showed an association of Wnt target gene up-regulation with increased intestinal adenomas in Apc1322T/+ mice (36). It is also possible that the observed increase in polyp number and size might result from a role for nuclear Apc in suppressing polyp progression, once the polyp is initiated. In this scenario, polyps would initiate at the same rate in ApcMin/mNLS and ApcMin/+ mice, but would more rapidly grow large enough for detection in the ApcMin/mNLS mice. Our finding of increased proliferation in polyps from ApcMin/mNLS mice compared to ApcMin/+ mice does not distinguish between these two scenarios, but does implicate nuclear Apc regulation of cell proliferation as a contributing factor to tumor suppression.

In the current study, three separate parameters each showed a response in the colon distinct from that seen in the jejunum or ileum. Epithelia from jejunum or ileum did not display elevated levels of either Apc or β-catenin (Fig. 3). In contrast, colon epithelia displayed Apc and β-catenin protein levels that were significantly higher in ApcmNLS/mNLS mice compared to Apc+/+ mice. This finding confirms that high levels of Apc do not always result in constitutive β-catenin degradation. Changes in expression of Wnt target genes were consistent with elevated canonical Wnt signaling in jejunum, ileum and colon tissues from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice compared to Apc+/+ mice (Fig. 4). However, BTEB2, a gene not regulated by canonical Wnt signaling, was unchanged in jejunum and ileum, but was elevated in colonic epithelial cells from ApcmNLS/mNLS mice compared to Apc+/+ mice. Finally, unlike small intestinal tissue, colon tissue from ApcMin/mNLS mice did not show elevated polyp size or multiplicity compared to ApcMin/+ mice (Fig. 7B, 7D). Why do the colon and small intestine tissues show distinct responses to manipulation of Apc NLSs? We speculate that this variability might result from potential alternate feedback responses (chromosomal instability, apoptosis, survival) dependent on tissue type. Moreover, colon tissue lacks villi, performs a distinct function and maintains a different flora than the small intestine. Although not completely understood, humans and rats with germline APC mutations are prone to colon polyps, whereas mice with similar Apc mutations have polyps predominantly in the small intestine. Any of these factors might contribute to the differences seen in colon and small intestinal tissue from ApcmNLS mice. Future studies utilizing the novel ApcmNLS/mNLS model might offer clues to some of these longstanding puzzles in Apc biology.

In summary, the novel ApcmNLS/mNLS mouse model contains a subtle alteration that inactivates both Apc NLSs. Increased expression of Wnt targets and increased proliferation in intestines of adult ApcmNLS/mNLS mice implicate nuclear Apc in control of cellular proliferation and Wnt signaling. The finding of increased numbers and size of small intestinal polyps in ApcMin/mNLS mice compared with ApcMin/+ mice implicates nuclear Apc in tumor suppression. Future studies of this novel mouse model will elucidate nuclear Apc contributions to other cellular events critical for tissue homeostasis, such as DNA repair, transcription regulation and cell cycle progression.

Materials and methods

Creating the Gene Replacement Vector

The homologous sequences of DNA used for the targeting construct were obtained from a lambda phage library of genomic DNA isolated from 129 mouse ES cells (generously provided by Kirk Thomas and Mario Capecchi, University of Utah). This library was screened for fragments of Apc containing the two primary Apc nuclear localization signals (NLSs). Following identification of an Apc NLS-containing plaque by hybridization to a radioactive probe, a 14 kb stretch of mouse genomic DNA (Apc exons 14, 15 and surrounding introns) was isolated from the phage and inserted into the pBluescript KSII+ vector (Stratagene). An EcoRI fragment containing both Apc NLSs was subcloned into the pUC19 vector. Mutations that inactivated each NLS and introduced novel restriction sites were inserted by PCR mutagenesis (Figure 1B). A second pUC19 vector was modified to destroy its EcoRI restriction site and introduce Nhe I and Not I sites. An 11,537 bp region of Apc (NheI/NotI) was subcloned into this modified vector. The EcoRI fragment of Apc containing wildtype NLSs was replaced by the same fragment with mutant NLSs. Using restriction sites for KpnI and AflII in the noncoding region 3’ to Apc exon 15, a tACE-Cre-Neor cassette, flanked by two LoxP sites was introduced into the pUC19 vector containing the Apc gene fragment with mutant Apc NLSs. This tACE-Cre-Neor cassette included a neomycin resistance gene (Neor) driven by the promoter for RNA polymerase II and was linked to a gene encoding Cre recombinase under control of the testes-specific murine angiotensin-converting enzyme (tACE) promoter (2). The HSV thymidine kinase gene controlled by the phosphoglycerate kinase (PGK) promoter was inserted upstream of the Apc homology sequences in the pUC19 vector to create the 19,947 bp targeting vector (Figure 1A).

Electroporation into Embryonic Stem Cells

The targeting construct DNA was cleaved with Not I restriction endonuclease to linearize at a unique site 3’ of the region homologous to Apc. Digestion with Not I was followed by two phenol/chloroform extractions before the linearized gene replacement vector was electroporated into R1 mouse embryonic stem cells (27) at the Transgenic and Gene-Targeting Institutional Facility at The University of Kansas Medical Center. Cells were selected for growth in 300µg/mL G418 (Cellgro) and 2µM ganciclovir (Roche). Following 8–10 days of culture in selective media, each surviving colony was picked and expanded into two separate wells. DNA was isolated from one well for genotype analysis and the cells in the remaining well were frozen in 96-well plates for injections.

Screening and Verifying Targeted ES cell lines

Identification of ES cell lines containing mutations in both Apc NLSs was accomplished using a two-step PCR screen and the following primer sets: wildtype Apc NLS1 forward and NLS2 reverse, wNLS1fw (5’-CTA AGA AAA AGA AGC CTA CTT CAC) and wNLS2rv (5’-GGC CTT TTC TTT TTT GGC ATG GC); mutant Apc NLS1 forward and NLS2 reverse, mNLS1fw (5’-GCA GCC GCG GCA CCT ACT) and mNLS2rv (5’-TTG AAG GCC TTT TTG CGG CC) (Figure 1C). To identify homologous cassette insertion at the 3’ end, a primer annealing to DNA in the LoxP/tACE promoter region of the tACE-Cre-Neor cassette (5’-CCT GGC CCA TGG AGA TCC AT) was used with a primer annealing to genomic Apc 3’ of the targeting construct (5’-CAT ACC ACC CAC CAT CCC TA) or with a primer annealing to the 3’ end of the targeting construct (TCT CCC ATT GCT TAT GGC AAC) as a positive control (Figure 1H). Cell lines were also screened for correct incorporation of the 5’ end of the targeting construct using PCR. The reverse primers wNLS2rv and mNLS2rv were used in conjunction with the following primer that anneals to a region of genomic DNA upstream of the 5’ end of the targeting construct: (5’-AAA TTG AAC TCA GGA CCT TCT C) (Figure 1F). PCR products digested with SstII produced a 6100bp DNA product if mutant Apc NLS1 was present (Figure 1G). Each cell line with correct homologous recombination was further evaluated by determining the karyotype of 40–50 cells.

Generation of Chimeric Mice

For the generation of chimeric mice, ApcmNLS/+ ES cells were injected into C57BL/6J blastocysts at the Gene Targeting and Transgenic Facility at the University of Virginia. Male chimeric mice that carried the mutant copy of Apc were bred to C57BL/6J females originally obtained from The Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, Maine). Black progeny were culled and agouti colored progeny were genotyped using tail DNA isolated following a protocol from The Jackson Laboratory (http://www.jax.org/imr/tail_nonorg.html) and PCR to screen for the presence of the mutant nuclear localization sites. Verification of selection cassette loss in the ApcmNLS/+ progeny was conducted using PCR with the following primers: forward primer, 5’-TCG GCC ATT GAA CAA GAT GGA-3’ and reverse primer, 5’-ATT CGC CGC CAA GCT CTT CA-3’ (Figure 1E).

Mouse Husbandry

Mice were maintained in the Animal Care Unit at the University of Kansas according to animal use statement number 137-01. The research complied with all relevant federal guidelines and institutional policies. The chimeric mice were bred with C57BL/6J mice from The Jackson Labs (Bar Harbor, Maine). ApcmNLS/+ progeny from the original mating of male chimeric mice with female C57BL/6J mice were repeatedly backcrossed to the inbred C57BL/6J mice 10–18 times to generate a line that was considered to be congenic (N10-N18). Detailed records including the date of birth, lineage, coat color, sex, genotype and date of sacrifice were maintained for each individual mouse. For the survival curve, N1 male and female ApcmNLS/+ mice were bred and F1 progeny were housed with same sex siblings for the duration of the study (n=18 for Apc+/+; 19 for ApcmNLS/+; and 18 for ApcmNLS/mNLS mice). Cause of death for mice in the survival study was not determined because mice were allowed to die naturally and thus most were not collected for many hours after their death. Mice were fed ad libitum with Purina Lab Diet 5001 and were housed in cages in adjoining animal rooms. Congenic mice weighed at different times between ages 6 and 14-weeks showed no significant differences comparing Apc+/+ and ApcmNLS/mNLS mice. ApcMin/+ mice were purchased from The Jackson Labs and were maintained by breeding males with C57BL/6J females. ApcMin/mNLS mice were generated by breeding male ApcMin/+ mice (from Jackson Labs) with congenic (N10-N15) female ApcmNLS/+ mice.

Mouse genotyping

After weaning, mouse pups were tagged with a metal ear tag or by injection of an implantable electronic transponder (Bio Medic Data Systems Inc.) into the subcutaneous space above the shoulders. The Apc genotype of each mouse pup was determined using isolated tail DNA and PCR to screen for the presence of the wild-type and mutant NLS coding sequences using the following primers: forward, 5’-TAGTGATGCGGTGAGTCCAA-3’ and reverse, 5’-ACCAAGTCCAACAAGCATCC-3’. Reaction conditions were: 94°C for 5 min., 35 cycles of 94°C for 1 min., 54°C for 1 min., 68°C for 1 min., final 3 min. at 68°C. PCR products (295 bps) were cut with SacII restriction enzyme. The restriction enzyme does not cut the wildtype allele but cuts the mutant allele into 2 fragments of 235 and 60-bp (Supplemental Fig. 4). The ApcMin allele was detected using the standard PCR protocol published by the Jackson Laboratories (http://jaxmice.jax.org).

Analysis of gross and microscopic pathology, polyp measurement

The gross and cellular histology of intestinal tissues were examined in the N1-N13 generations of ApcmNLS mice and in fourteen-week old ApcMin/+ mice and ApcMin/mNLS mice. For each mouse, GI tract from the stomach to the anal canal was dissected, opened longitudinally and fixed in 10% buffered formalin. Using a dissecting microscope, an investigator blind to the animal’s genotype examined the intestinal luminal surface for any irregularities and polyps. Regions of tissue with abnormalities were recorded, removed from the surrounding tissue and stored in 10% buffered formalin. Tissue that appeared grossly abnormal was sent for pathologic evaluation. Intestinal polyps were located and diameter measured with the aid of a dissection microscope (Leica, MZ8) equipped with an eyepiece graticule and calibrated to a 50-mm scale stage micrometer with 0.1 and 0.01-mm graduation. Fourteen-week old ApcMin/mNLS and ApcMin/+ mice were analyzed for this study.

Evaluation of proliferation in intestinal epithelia

For proliferation analysis, congenic mice were injected with EdU, and intestinal tissue prepared and stained as described (28). Briefly, at the time of sacrifice, mouse small and large intestines were removed and opened lengthwise. The colon, and proximal, middle and distal regions of the small intestine were individually rolled as described (19) to form multiple “Swiss Rolls”. The sections of rolled colon and small intestine were incubated in fixative [4% paraformaldehyde, 0.1% triton X-100, in PBS] on ice for 1 hour, rinsed in PBS and incubated in 2.5 M sucrose at 4°C overnight. After PBS rinse, rolled tissue sections were frozen in OCT tissue freezing media (VWR) at −20°C. Sections were sliced immediately or stored at −80°C. Tissue cryosections (7µm) were made using a Leica CM1900 cryotome and adhered to glass slides coated with histomount (Invitrogen) for immunohistochemistry. Slides were air dried for approximately 1 min. then tissue slices were permeabilized in 70% methanol before staining for EdU as described (40). For each tissue in each genotype, 50–100 crypts were analyzed for proliferation by scoring the number of EdU-positive cells and the total cell number by DAPI stain in a crypt cross section. Samples were coded so that analysis could be performed by a trained observer blind to the study parameters. Data from 3 mice of each genotype were collected to determine proliferation in the various intestinal tissues. Only crypts with 40 or more cells in cross section were scored.

Immunohistochemistry of intestinal epithelia and polyps

Tissues were fixed in 10% saline-buffered formalin 16–20 hr then stored in 70% ethanol. Tissues were embedded in paraffin and sectioned at 6-µm. Immunohistochemistry for β-catenin and Ki-67 was performed using the Histomouse kit® (Invitrogen, Cat# 95–9541) according to the manufacturer’s protocol and with mouse monoclonal anti-β-catenin antibodies (1:100, BD Biosciences, Cat# 610153) and rat anti mouse Ki-67 antibodies (1:20, Dako, Cat# M7249). Tissues were coded allowing the analysis to be performed by an observer blind to the tissue genotype. Normal appearing Jejunum, Ileum and colon tissues from at least 3 mice of each genotype (Apc+/+, ApcmNLS/+, and ApcmNLS/mNLS) were examined for β-catenin localization. In addition, 6 polyps from 4 ApcMin/+ mice and 7 polyps from 3 ApcMin/mNLS mice were examined for β-catenin localization. After surveying the entire length of tissue for β-catenin localization, the average distribution was recorded and representative images captured using 20X and 40X objectives. The polyps were also scored for Ki-67 by counting Ki-67 positive cells per field at 40X magnification. Three fields were photographed and scored for each polyp. The p-values for all proliferation studies were calculated using unpaired, two-tailed t-tests and GraphPad Prism software.

Isolation of mouse intestinal epithelial cells

Isolation of intestinal epithelial cells was performed with modifications to a previous protocol (50). Immediately after sacrifice, small and large intestines were removed from congenic mice, opened lengthwise and rinsed with cold PBS. Tissue was incubated in 0.04% sodium hypochlorite for 15 min. on ice and then rinsed in cold PBS. The colon and small intestine were then incubated on ice for 15 min in individual 15mL conical tubes containing EDTA/DTT solution (1.5–3mM EDTA and 0.5mM DTT in PBS). EDTA/DTT solution was poured off and replaced with cold PBS. Tubes were shaken forcefully for 10 sec. to release the epithelial cells from the underlying tissue. The intestinal tissue was removed and placed in a fresh 15mL conical tube of EDTA/DTT solution, and the process was repeated two additional times. The released epithelial cells were collected by centrifugation at 700xg for 5 min. at room temperature. Pellets of the colon epithelia from all three rounds of extraction were resuspended in PBS with protease inhibitors and combined into one sample. Because the surface area of the small intestine is significantly greater than that of the colon, there was no need to combine the epithelial tissue from the replicate extractions. The small intestinal epithelial cells from the second round of extraction were used in the experiments described here. Cell pellets were lysed in Reporter Lysis Buffer (Promega) with protease inhibitors [aprotinin, leupeptin and pepstatin each at 10 µg/ml and 1 mM PMSF] and briefly sonicated. Samples were boiled after addition of Sample Buffer [3X Sample Buffer: 6% w/v Sodium Dodecyl Sulfate, 30% Glycerol, 150mM Tris pH 6.8, ~0.2mg/mL Bromophenol Blue] and resolved by SDS-PAGE before transfer to nitrocellulose membranes.

Immunoblot analysis of Apc and β-catenin in intestinal tissue and MEF fractionation

Immunoblots were processed as described (49). Membranes were probed with the following primary antibodies diluted as indicated in 5% nonfat dry milk/TBST: rabbit anti-APC M2 (1:3000,(48)), mouse anti-β-catenin (1:2000, BD Biosciences, Cat# 610153), mouse anti-α-tubulin (1:50, Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank), rabbit anti-fibrillarin (1:1000, ab5821 AbCam), β-actin (1:2000,Sigma). The following secondary antibodies were diluted as indicated: HRP goat anti-mouse (1:10–25,000, Zymed) and HRP goat anti-rabbit (1:10–25,000, Bio-Rad). Blots were developed using Western Lightning Chemiluminescence Reagent Plus (PerkinElmer) or SuperSignal West Femto Maximum Sensitivity Substrate (Pierce) and a Kodak Image Station 4000R. Band analysis was conducted using Kodak ID Image Analysis Software with protein levels first normalized to β-actin and then values for the Apc+/+ samples set to 1. The p-values were calculated using Mann-Whitney nonparametric test. MEFs of each genotype were isolated from congenic (N10-N18) mice on three independent occasions following the protocol as described (26). Independently isolated early passage MEFs were subjected to fractionation in five independent experiments as described (31). Nuclear Apc and β-catenin were calculated based on the band intensity in the nuclear fraction divided by the intensity of the nuclear plus the cytoplasmic bands. The p-values were calculated using unpaired, two-tailed t-tests and GraphPad Prism software.

Analysis of mRNA using real time RT-PCR

For preparation of RNA, 200-µl of suspended epithelial cells were added to 1-ml Trizol® (invitrogen) and tubes were stored at −80°C until used. RNA extraction was performed using Trizol® according to the manufacturer’s protocol. For making cDNA, 1µg total RNA was incubated for 1 hour at 42°C with the cDNA reaction mix containing 1 mM dNTPs, 1µg random hexamer primers (NEB), 1X M-MLuV enzyme buffer (NEB) and 200 units M-MLuV RT enzyme (NEB). The reverse transcriptase enzyme was then inactivated by heating at 95°C for 5 minutes. Quantitative PCR was carried out for c-Myc, Axin2, Cyclin D1, BTEB2, and Hath1 cDNA from the mouse intestinal epithelial cells. The cDNA of the house keeping gene HGPRT was used as an internal control. Table I shows the primers used.

Table I.

primers used for quantifying canonical and non-canonical Wnt targets in mouse intestinal epithelial cells

| Gene | Forward primer | Reverse primer |

|---|---|---|

| c-Myc | 5’- TCCTGTACCTCGTCCGATTC-3’ | 5’- GGTTTGCCTCTTCTCCACAG-3’ |

| Axin2 | 5’- TGTGAGATCCACGGAAACAG-3’ | 5’- CTGCGATGCATCTCTCTCTG-3’ |

| Cyclin D1 | 5’- TTGACTGCCGAGAAGTTGTG-3’ | 5’- AGGGTGGGTTGGAAATGAAC-3’ |

| Hath1 | 5’-ACATCTCCCAGATCCCACAG-3’ | 5’-ACAACGATCACCACAGACCA-3’ |

| BTEB2 | 5’-CTCCGGAGACGATCTGAAAC-3’ | 5’-GAACTGGAGGGAGCTGAGG-3’ |

| HGPRT | 5’- TGCTCGAGATGTCATGAAGG-3’ | 5’- TATGTCCCCCGTTGACTGAT-3’ |

PCR reactions were performed using a DNA engine Opticon 2 system (MJ research) with SYBR green detection system. The total reaction volume was 25µl containing 1X DyNAmo™ HS SYBR® Green qPCR Kit (Finnzymes), 15 picomoles of each primer and 3 µl of 1:2.5 diluted cDNA. Each reaction was done in triplicate and repeated three times. The reaction condition was initial denaturation at 95°C for 15 minutes followed by 40 cycles of denaturation at 94°C for 20 seconds, annealing at 54°C for 30 seconds and extension at 72°C for 30 seconds. The fluorescence was measured at the end of every cycle and a melting curve was analyzed between 40°C and 95°C with 0.2°C increment. Samples were only included in the analysis if the melting curve was a single peak at the expected temperature. Average ΔC(T) was calculated for different genotypes relative to the house keeping gene transcript while ΔΔC(T) of Wnt target cDNA for ApcmNLS/+ and ApcmNLS/mNLS was calculated relative to the Apc+/+ mice. The p-values were calculated using Mann-Whitney nonparametric test and GraphPad Prism software.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Figure 1. Mutations in APC NLS1 and NLS2 do not interfere with axin or β-catenin binding. 293T cells were transfected with expression constructs for flag-tagged full-length APC or APC with mutations in both NLS1 and NLS2 (APCmNLS1,2). Anti-flag antibody was used to precipitate protein from transfected cells (Tfxn) or control untransfected cells. Precipitated proteins were analyzed for the presence of axin and β-catenin by immunoblot.

Supplemental Figure 2. β-catenin distribution similar in intestinal epithelia from Apc+/+, ApcmNLS/+, and ApcmNLS/mNLS mice. (A) At least three mice from each genotype were analyzed for β-catenin localization. In all normal intestinal tissues, β-catenin appeared predominantly at the cell-cell junctions, with occasional nuclear distribution in cells near the crypt base (red arrows). (B) Determination of crypts that contained any cells with nuclear β-catenin revealed a similar number in mice from each genotype (p=0.826).

Supplemental Figure 3. ApcMin/mNLS mice have more polyps than ApcMin/+ mice. Polyps identified in 14-week old mice (see Fig. 7) are presented as scatter plots. Lines indicate the sample median.

Supplemental Figure 4. Genotyping ApcmNLS/mNLS mice. Genomic DNA from congenic mice was amplified by PCR using the primers described in Materials and Methods. Product DNA was cut with SacII restriction enzyme to distinguish ApcmNLS from Apc+.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by RO1 CA10922 from the National Cancer Institute and 5P20 RR15563.

The authors extend their gratitude to Alan Godwin, Kirk Thomas, and Mario Capecchi for their advice in generation of the knock-in mouse and for the λ phage library, and tACE-Cre-Neor and TkHSV-containing constructs. The authors thank Marc Roth, Areli Monarrez, Ashrita Abraham, and Travis Friesen for technical assistance, staff at the University of Kansas Animal Care Unit for excellent mouse husbandry, and David Davido for critical reading of the manuscript. The authors also thank Reka Nagy and Drs Andras Nagy, Janet Rossant, and Wanda Abramow-Newerly (Mount Sinai Hospital) for the mouse R1 ES cells.

References

- 1.Anderson CB, Neufeld KL, White RL. Subcellular distribution of Wnt pathway proteins in normal and neoplastic colon. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:8683–8688. doi: 10.1073/pnas.122235399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bunting M, Bernstein KE, Greer JM, Capecchi MR, Thomas KR. Targeting genes for self-excision in the germ line. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1524–1528. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.12.1524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheung AF, Carter AM, Kostova KK, Woodruff JF, Crowley D, Bronson RT, Haigis KM, Jacks T. Complete deletion of Apc results in severe polyposis in mice. Oncogene. 2009;29:1857–1864. doi: 10.1038/onc.2009.457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Colnot S, Niwa-Kawakita M, Hamard G, Godard C, Le Plenier S, Houbron C, Romagnolo B, Berrebi D, Giovannini M, Perret C. Colorectal cancers in a new mouse model of familial adenomatous polyposis: influence of genetic and environmental modifiers. Lab Invest. 2004;84:1619–1630. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dingwall C, Sharnick SV, Laskey RA. A Polypeptide Domain That Specifies Migration of Nucleoplasmin into the Nucleus. Cell. 1982;30:449–458. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(82)90242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fagman H, Larsson F, Arvidsson Y, Meuller J, Nordling M, Martinsson T, Helmbrecht K, Brabant G, Nilsson M. Nuclear accumulation of full-length and truncated adenomatous polyposis coli protein in tumor cells depends on proliferation. Oncogene. 2003;22:6013–6022. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fodde R, Edelmann W, Yang K, van Leeuwen C, Carlson C, Renault B, Breukel C, Alt E, Lipkin M, Khan PM. A targeted chain-termination mutation in the mouse Apc gene results in multiple intestinal tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 1994;91:8969–8973. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.8969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fodde R, Kuipers J, Rosenberg C, Smits R, Kielman M, Gaspar C, van Es JH, Breukel C, Wiegant J, Giles RH, Clevers H. Mutations in the APC tumour suppressor gene cause chromosomal instability. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:433–438. doi: 10.1038/35070129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Galea MA, Eleftheriou A, Henderson BR. ARM domain-dependent nuclear import of adenomatous polyposis coli protein is stimulated by the B56 alpha subunit of protein phosphatase 2A. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:45833–45839. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M107149200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Giles RH, van Es JH, Clevers H. Caught up in a Wnt storm: Wnt signaling in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2003;1653:1–24. doi: 10.1016/s0304-419x(03)00005-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gorlich D, Prehn S, Laskey RA, Hartmann E. Isolation of a protein that is essential for the first step of nuclear protein import. Cell. 1994;79:767–778. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(94)90067-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.He TC, Sparks AB, Rago C, Hermeking H, Zawel L, da Costa LT, Morin PJ, Vogelstein B, Kinzler KW. Identification of c-MYC as a target of the APC pathway. Science. 1998;281:1509–1512. doi: 10.1126/science.281.5382.1509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Henderson B. Nuclear-cytoplasmic shuttling of APC regulates β-catenin subcellular localization and turnover. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2:653–660. doi: 10.1038/35023605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ishikawa T-o, Tamai Y, Li Q, Oshima M, Taketo MM. Requirement for tumor suppressor Apc in the morphogenesis of anterior and ventral mouse embryo. Developmental Biology. 2003;253:230–246. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(02)00020-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jaiswal AS, Narayan S. A novel function of adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) in regulating DNA repair. Cancer Letters. 2008;271:272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.06.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kan Y, Winfried E, Kunhua F, Kirkland L, Venkateswara RK, Riccardo F, Khan PM, Raju K, Martin L. A mouse model of human familial adenomatous polyposis. The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 1997;277:245–254. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kaplan KB, Burds AA, Swedlow JR, Bekir SS, Sorger PK, Nathke IS. A role for the Adenomatous Polyposis Coli protein in chromosome segregation. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:429–432. doi: 10.1038/35070123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kielman MF, Rindapaa M, Gaspar C, van Poppel N, Breukel C, van Leeuwen S, Taketo MM, Roberts S, Smits R, Fodde R. Apc modulates embryonic stem-cell differentiation by controlling the dosage of beta-catenin signaling. Nat Genet. 2002;32:594–605. doi: 10.1038/ng1045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Magnus HA. Observations on the presence of intestinal epithelium in the gastric mucosa. The Journal of Pathology and Baceriology. 1937;44:389–398. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mattaj IW, Englmeier L. Nucleocytoplasmic transport: the soluble phase. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:265–306. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyoshi Y, Ando H, Nagase H, Nishisho I, Horii A, Miki Y, Mori T, Utsunomiya J, Baba S, Petersen G, Hamilton S, Kinzler K, Vogelstein B, Nakamura Y. Germ-line mutations of the APC gene in 53 familial adenomatous polyposis patients. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1992;89:4452–4456. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.10.4452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miyoshi Y, Nagase H, Ando H, Horii A, Ichii S, Nakatsuru S, Aoki T, Miki Y, Mori T, Nakamura Y. Somatic mutations of the APC gene in colorectal tumors: mutation cluster region in the APC gene. Human Molecular Genetics. 1992;1:229–233. doi: 10.1093/hmg/1.4.229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Moser A, Pitot H, Dove W. A dominant mutation that predisposes to multiple intestinal neoplasia in the mouse. Science. 1990;247:322–324. doi: 10.1126/science.2296722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moser AR, Mattes EM, Dove WF, Lindstrom MJ, Haag JD, Gould MN. ApcMin, a mutation in the murine Apc gene, predisposes to mammary carcinomas and focal alveolar hyperplasias. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1993;90:8977–8981. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.19.8977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Munemitsu S, Albert I, Souza B, Rubinfeld B, Polakis P. Regulation of intracellular beta-catenin levels by the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) tumor-suppressor protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:3046–3050. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.7.3046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nagy A, Gertsenstein M, Vintersten K, Behringer R. Maipulating the Mouse Embryo A Laboratory Manual. third ed. New York: Cold Spring Harbor Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nagy A, Rossant J, Nagy R, Abramow-Newerly W, Roder JC. Derivation of completely cell culture-derived mice from early-passage embryonic stem cells. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. 1993;90:8424–8428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.18.8424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nathke IS, Adams CL, Polakis P, Sellin JH, Nelson J. The adenomatous polyposis coli tumor suppressor protein localizes to plasma membrane sites involved in active cell migration. J Cell Biol. 1996;134:165–179. doi: 10.1083/jcb.134.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neufeld KL. Nuclear Functions of APC. In: Nathke IS, McCartney B, editors. Adenomatous Polyposis Coli Protein. Landes Bioscience; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Neufeld KL. Nuclear Functions of APC. Adv. Exp. Med Biol. 2009;656:13–29. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-1145-2_2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Neufeld KL, White RL. Nuclear and cytoplasmic localizations of the adenomatous polyposis coli protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3034–3039. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neufeld KL, Zhang F, Cullen BR, White RL. APC-mediated down-regulation of β-Catenin activity involves nuclear sequestration and nuclear export. EMBO Reports. 2000;1:519–523. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Neufeld KL, Zhang F, Cullen BR, White RL. APC-mediated downregulation of beta-catenin activity involves nuclear sequestration and nuclear export. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:519–523. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvd117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Oshima M, Oshima H, Kitagawa K, Kobayashi M, Itakura C, Taketo M. Loss of Apc heterozygosity and abnormal tissue building in nascent intestinal polyps in mice carrying a truncated Apc gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92:4482–4486. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.10.4482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters R. Fluorescence microphotolysis to measure nucleocytoplasmic transport and intracellular mobility. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Reviews on Biomembranes. 1986;864:305–359. doi: 10.1016/0304-4157(86)90003-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pollard P, Deheragoda M, Segditsas S, Lewis A, Rowan A, Howarth K, Willis L, Nye E, McCart A, Mandir N, Silver A, Goodlad R, Stamp G, Cockman M, East P, Spencer–Dene B, Poulsom R, Wright N, Tomlinson I. The Apc1322T Mouse Develops Severe Polyposis Associated With Submaximal Nuclear β-Catenin Expression. Gastroenterology. 2009;136:2204–2213. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.02.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Qian J, Sarnaik AA, Bonney TM, Keirsey J, Combs KA, Steigerwald K, Acharya S, Behbehani GK, Barton MC, Lowy AM, Groden J. The APC Tumor Suppressor Inhibits DNA Replication by Directly Binding to DNA via Its Carboxyl Terminus. Gastroenterology. 2008;135:152–162. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.03.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rosin-Arbesfeld R, Cliffe A, Brabletz T, Bienz M. Nuclear export of the APC tumour suppressor controls beta-catenin function in transcription. Embo J. 2003;22:1101–1113. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rosin-Arbfeld R, Townsley F, Bienz M. The APC tumour suppressor has a nuclear export function. Nature. 2000;406:1009–1012. doi: 10.1038/35023016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Salic A, Mitchison TJ. A chemical method for fast and sensitive detection of DNA synthesis in vivo. Proc. Natl. Acad Sci. 2008;105:2415–2420. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712168105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sasai H, Masaki M, Wakitani K. Suppression of polypogenesis in a new mouse strain with a truncated Apc(Delta474) by a novel COX-2 inhibitor, JTE-522. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:953–958. doi: 10.1093/carcin/21.5.953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Sena P, Saviano M, Monni S, Losi L, Roncucci L, Marzona L, Pol AD. Subcellular localization of beta-catenin and APC proteins in colorectal preneoplastic and neoplastic lesions. Cancer Lett. 2006;241:203–212. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2005.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sierra J, Yoshida T, Joazeiro CA, Jones KA. The APC tumor suppressor counteracts beta-catenin activation and H3K4 methylation at Wnt target genes. Genes Dev. 2006;20:586–600. doi: 10.1101/gad.1385806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Smith KJ, Johnson KA, Bryan TM, Hill DE, Markowitz S, Willson JK, Paraskeva C, Petersen GM, Hamilton SR, Vogelstein B, Kinzler K. The APC gene product in normal and tumor cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 1993;90:2846–2850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.7.2846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Smits R, Kielman MF, Breukel C, Zurcher C, Neufeld K, Jagmohan-Changur S, Hofland N, van Dijk J, White R, Edelmann W, Kucherlapati R, Khan PM, Fodde R. Apc1638T: a mouse model delineating critical domains of the adenomatous polyposis coli protein involved in tumorigenesis and development. Genes Dev. 1999;13:1309–1321. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.10.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taketo MM. Mouse models of gastrointestinal tumors. Cancer Science. 2006;97:355–361. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00190.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tetsu O, McCormick F. Beta-catenin regulates expression of cyclin D1 in colon carcinoma cells. Nature. 1999;398:422–426. doi: 10.1038/18884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wang Y, Azuma Y, Friedman DB, Coffey R, Neufeld KL. Novel Association of APC with Intermediate Filaments Identified using a New Versatile APC Antibody. BMC Cell Biology. 2009;10:75–88. doi: 10.1186/1471-2121-10-75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wang Y, Azuma Y, Moore D, Osheroff N, Neufeld KL. Interaction between Tumor Suppressor APC and Topoisomerase IIα: Implication for the G2/M Transition. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:4076–4085. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whitehead RH, Demmler K, Rockman SP, Watson NK. Clonogenic growth of epithelial cells from normal colonic mucosa from both mice and humans. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:858–865. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70344-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang F, White R, Neufeld K. Phosphorylation near nuclear localization signal regulates nuclear import of APC protein. Proc. Natl. Acad USA. 2000;97:12577–12582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.230435597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang F, White RL, Neufeld KL. Cell density and phosphorylation control the subcellular localization of adenomatous polyposis coli protein. Mol Cell Biol. 2001;21:8143–8156. doi: 10.1128/MCB.21.23.8143-8156.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Figure 1. Mutations in APC NLS1 and NLS2 do not interfere with axin or β-catenin binding. 293T cells were transfected with expression constructs for flag-tagged full-length APC or APC with mutations in both NLS1 and NLS2 (APCmNLS1,2). Anti-flag antibody was used to precipitate protein from transfected cells (Tfxn) or control untransfected cells. Precipitated proteins were analyzed for the presence of axin and β-catenin by immunoblot.

Supplemental Figure 2. β-catenin distribution similar in intestinal epithelia from Apc+/+, ApcmNLS/+, and ApcmNLS/mNLS mice. (A) At least three mice from each genotype were analyzed for β-catenin localization. In all normal intestinal tissues, β-catenin appeared predominantly at the cell-cell junctions, with occasional nuclear distribution in cells near the crypt base (red arrows). (B) Determination of crypts that contained any cells with nuclear β-catenin revealed a similar number in mice from each genotype (p=0.826).

Supplemental Figure 3. ApcMin/mNLS mice have more polyps than ApcMin/+ mice. Polyps identified in 14-week old mice (see Fig. 7) are presented as scatter plots. Lines indicate the sample median.

Supplemental Figure 4. Genotyping ApcmNLS/mNLS mice. Genomic DNA from congenic mice was amplified by PCR using the primers described in Materials and Methods. Product DNA was cut with SacII restriction enzyme to distinguish ApcmNLS from Apc+.