Abstract

Staphylococcus aureus is responsible for the vast majority of bacterial skin infections in humans. The propensity for S. aureus to infect skin involves a balance between cutaneous immune defense mechanisms and virulence factors of the pathogen. The tissue architecture of the skin is different than other epithelia especially since it possesses a corneal layer, which is an important barrier that protects against the pathogenic microorganisms in the environment. The skin surface, epidermis and dermis each contribute to host defense against S. aureus. Conversely, S. aureus utilizes various mechanisms to evade these host defenses to promote colonization and infection of the skin. This review will focus on host-pathogen interactions at the skin interface during the pathogenesis of S. aureus colonization and infection.

Introduction

Staphylococcus aureus skin infections

S. aureus is a gram positive extracellular bacterium that is responsible for the vast majority of skin infections, including superficial infections such as impetigo and infected abrasions as well as more invasive infections such as cellulitis, folliculitis, subcutaneous abscesses and infected ulcers and wounds [1;2]. A large epidemiological study conducted in the United States found that S. aureus skin infections result in 11.6 million outpatient and emergency room visits and nearly 500,000 hospital admissions per year [1]. These S. aureus skin infections represent a major threat to public health given the massive numbers of infections as well as the widespread emergence of antibiotic resistant strains such as methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA), including hospital- and community-acquired MRSA (CA-MRSA) infections [3-5]. Furthermore, the USA300 isolate, which is the most common community-acquired MRSA strain in the United States, is highly virulent and frequently associated with skin infections [3-5]. In this review, we will describe key interactions between the host and pathogen during S. aureus colonization of the skin (and mucosa), which is a risk factor for subsequent infection, and during different types of S. aureus skin infections that are categorized according to the anatomic site in the skin that is involved. Colonization by S. aureus occurs when S. aureus exists as a commensal organism on the surface of the skin (or mucosa) without any signs or symptoms of an infection (e.g. warmth, erythema, edema, pain/tenderness and drainage of pus) [6;7]. Impetigo is characterized by honey-colored crusted sores and erosions (and sometimes vesicles) on the surface of the skin and is caused by S. aureus infection of the epidermis. Cellulitis appears as a warm and erythematous enlarging plaque that results from a S. aureus infection that involves the dermis and subcutaneous layers of the skin [3-5]. Folliculitis clinically presents as follicularly-based erythematous papules and pustules and occurs when one or more hair follicles are infected with S. aureus [3-5]. Subcutaneous abscesses (which are also called boils) present as erythematous and edematous nodules that result from a deep S. aureus infection of a hair follicle and surrounding skin tissue [3-5]. Ulcers and wounds appear as open sores or craters in the skin. If they become infected, they are often drain purulent material and are surrounded by warmth and erythema as a result of a S. aureus infection that involves the deep dermis and subcutaneous tissues in an around the ulcer or wound [3-5].

Architecture of the skin

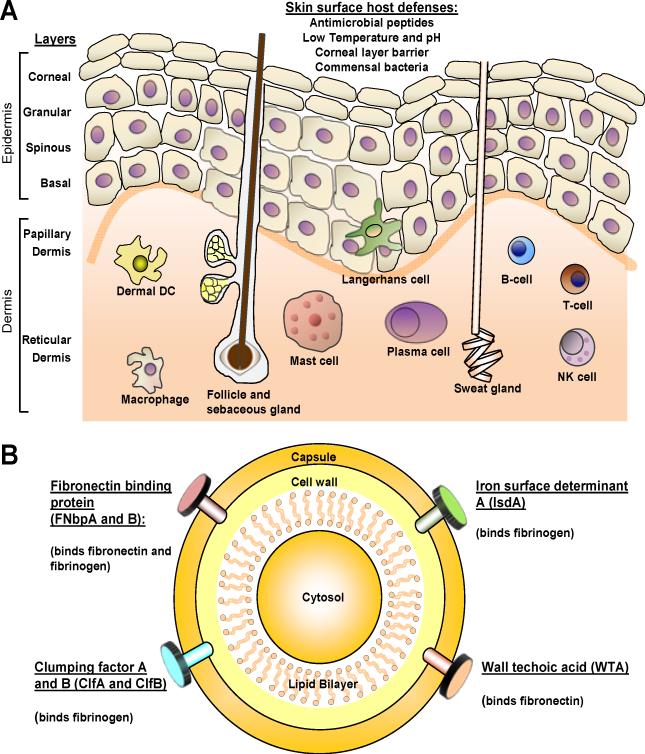

The skin is an important barrier that protects the body from pathogenic microorganisms encountered in the environment (Fig. 1A). The outermost layer of the skin, the corneal layer, is a unique layer that is not present in other epithelia that are also exposed to the environment such as the gut and lung [8;9]. The corneal layer is comprised of terminally differentiated keratinocytes that are devoid of organelles and contain highly crosslinked keratin fibrils [8;9]. The corneal layer functions as the major physical barrier of the skin. Beneath the corneal layer are the granular, spinous and basal layers of the epidermis. The epidermis is continuously being reformed as keratinocytes migrate from the basal layer to the corneal layer, where they are eventually shed [8;9]. Below the epidermis is the dermis, which is essentially a fibrous stroma consisting of collagen and elastin fibers [8;9]. The dermis can be subdivided into the papillary dermis, which is the uppermost layer between the rete ridges of the epidermis, and the deeper reticular dermis. There are also skin appendages such as sweat glands (eccrine and apocrine), sebaceous glands and hair follicles that span these layers and open onto the skin surface. Finally, the vasculature of the skin includes a superficial and deep plexus, with additional networks around skin appendages. The superficial plexus is comprised of arterioles and venules that are interconnected by capillary loops within the papillary dermis.

Figure 1. Host and pathogen interactions during S. aureus colonization.

A. The surface of the skin has constitutive properties such as a low temperature and pH, skin commensals and antimicrobial peptides that resist S. aureus colonization. The epidermis is composed of layers of keratinocytes, including the corneal, granular, spinous, and basal layers. There are sweat glands, sebaceous glands, and hair follicles that span these layers. In addition, there are many resident immune cells in skin that participate in immune responses, including Langerhans cells in the epidermis and dermal dendritic cells, macrophages, mast cells, T and B cells, plasma cells and NK cells in the dermis. B. S. aureus colonization requires adherence to the surface of the skin (and nasal mucosa), which is mediated by S. aureus surface components such as fibronectin-binding protein A (Fnbp A) and Fnbp B, fibrinogen-binding proteins (ClfA and ClfB), iron regulated surface determinant A (IsdA) and wall teichoic acid (WTA). Immune evasion is also mediated by IsdA, which evades host antimicrobial responses.

In addition to a physical barrier, the skin is also an immunologic barrier. The keratinocytes in the epidermis express pattern recognition receptors (PRRs), such as Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain (NOD)-like receptors that recognize pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) of microorganisms [8;9]. After recognition of PAMPs, PRRs trigger production of proinflammatory mediators such as cytokines, chemokines and antimicrobial peptides to initiate early innate cutaneous immune responses [8;9]. These early cutaneous immune responses include activation of the endothelial cells that line the skin vasculature to promote recruitment of immune cells from the circulation to the skin [8;9]. In addition, there are numerous resident immune cells in the skin. In the epidermis there are dendritic cells called Langerhans cells [8;9]. In the dermis, there are dermal dendritic cells, macrophages, mast cells, T and B cells, plasma cells and NK cells [8;9]. Each of these cell types can participate in cutaneous immune responses, including host defense against pathogens and in various immune-based skin diseases such as allergic contact dermatitis, atopic dermatitis and psoriasis [8;9]. In this review, we will focus on the interaction between S. aureus and the skin in the pathogenesis of colonization and skin infections.

Host-pathogen interactions during skin colonization

S. aureus frequently colonizes the skin and mucosa of humans. In the United States, it is estimated that approximately 30% of healthy individuals are colonized in the skin or mucosa with S. aureus [6]. Colonization by S. aureus is determined by host factors and commensal organisms that resist colonization versus S. aureus virulence factors that facilitate colonization. It is critical to understand these mechanisms as colonization is an important risk factor for subsequent S. aureus infection [7].

Host factors that inhibit colonization

The surface of the skin has constitutive properties that prevent colonization and infection by S. aureus (Fig. 1A). First, the surface of the skin has a low temperature and pH that resist microbial growth [10;11]. With particular relevance to S. aureus, the epidermal structural component filaggrin has been shown to be broken down during epidermal differentiation into urocanic acid and pyrrolidone carboxylic acid [12]. These breakdown products not only contribute to the low pH of the skin surface but also have been shown to reduce the growth of S. aureus and decrease expression of bacterial factors involved in colonization such as clumping factor B (ClfB) and fibronectin binding protein A (FnbpA) (see below) [12]. Second, normal commensal organisms on the skin surface such as S. epidermidis, P. acnes and Malassezia spp. occupy microbial niches, which prevent colonization and invasion by S. aureus and other pathogens [10;11]. Skin commensals have also been shown to directly inhibit S. aureus colonization of skin and nasal mucosa. For example, S. epidermidis secretes a serine protease called Esp, which inhibits colonization by S. aureus by destroying S. aureus biofilms [13]. S. epidermidis also produces phenol-soluble modulins (PSMγ and PSMδ) that have direct antimicrobial activity against S. aureus [14]. Finally, S. epidermidis activates TLR2 on keratinocytes, leading to production of antimicrobial peptides (e.g. human β-defensin 2 [hBD2], hBD3 and RNase 7), which amplify the immune response and promote killing of S. aureus [15;16]. Finally, there are antimicrobial peptides produced by keratinocytes that are present in the corneal layer and on the skin surface that have bacteriostatic or bactericidal activity against S. aureus, including hBD2, hBD3, LL-37 (cathelicidin) and RNase 7 [17-20]. The importance of antimicrobial peptides in host defense against S. aureus colonization is demonstrated by the increased S. aureus colonization of skin lesions of atopic dermatitis, which have been shown to have decreased levels of β-defensins and cathelicidin [21].

S. aureus virulence factors that promote colonization

One important mechanism to promote colonization is S. aureus adherence to surface components such as fibrinogen, fibronectin and cytokeratins of nasal epithelium or epidermal keratinocytes. S. aureus utilizes microbial surface components recognizing adhesive matrix molecules (MSCRAMMs) to bind to these components, including fibronectin-binding protein A (Fnbp A) and Fnbp B, fibrinogen-binding proteins (ClfA and ClfB), iron regulated surface determinant A (IsdA) and wall teichoic acid (WTA) (Fig. 1B) [22-25]. With particular relevance to S. aureus binding to human skin, skin lesions from atopic dermatitis patients, which are highly susceptible to S. aureus colonization, have increased Th2 cytokines (such as IL-4) that enhance S. aureus-mediated fibronectin and fibrinogen binding [25;26]. In addition, S. aureus produces superantigens such as staphylococcal enterotoxins A and B (SEA and SEB) and toxic shock syndrome toxin-1 (TSST-1) that have been shown to skew the cutaneous immune response towards the Th2 cytokine profile, which might contribute to the increased colonization of S. aureus in atopic dermatitis [27]. S. aureus also has mechanisms to evade host antimicrobial peptide responses. For example, IsdA enhances bacterial cellular hydrophobicity, which renders S. aureus resistant to bactericidal human skin fatty acids (which are present in sebum) as well as to β-defensins and cathelicidin [28]. Furthermore, S. aureus secretes a protein called aureolysin, which is an extracellular metalloproteinase that inhibits cathelicidin antimicrobial activity [29]. Taken together, there are a variety of S. aureus-derived factors that facilitate binding and survival of S. aureus to promote colonization of human nasal mucosa and skin.

Host-pathogen interactions during infection

Cutaneous host defense mechanisms against infection

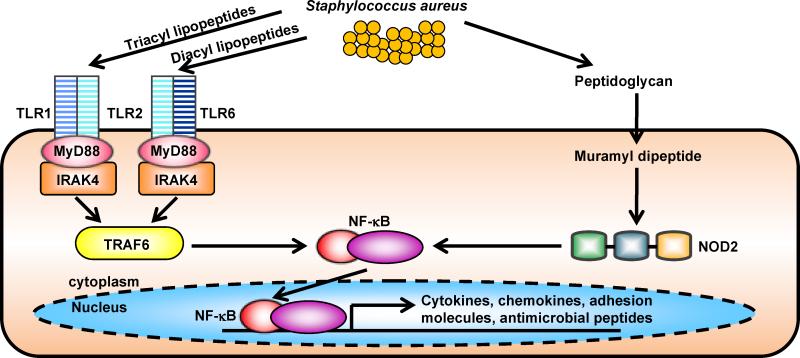

There are several cutaneous immune responses that have been shown to protect against S. aureus skin infections. Keratinocytes and other resident cells in the skin express PRRs that recognize components of S. aureus (Fig. 2) [30]. In particular, keratinocytes express TLR2 on the cell membrane, which can heterodimerize with TLR1 or TLR6 to recognize tri-acyl and diacyl lipopeptides (including S. aureus lipoteichoic acid), respectively [30]. In addition to TLRs, keratinocytes also express a cytoplasmic PRR, NOD2, which recognizes muramyl-dipeptide, a breakdown product of S. aureus peptidoglycan [31]. Triggering of these PRRs results in activation of signaling cascades that leads to production of pro-inflammatory cytokines, chemokines and antimicrobial peptides [32].

Figure 2. Pattern recognition receptors in host defense against S. aureus skin infections.

A. Keratinocytes express pattern recognition receptors such as Toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), which recognizes S. aureus lipopeptides and lipoteichoic acid, and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain containing 2 (NOD2), which recognizes the S. aureus peptidoglycan breakdown product muramyl peptide. Both TLR2 and NOD2 signaling leads to activation of NF-κB and other transcription factors that induce transcription of proinflammatory mediators (cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules and antimicrobial peptides) involved in cutaneous host defense against S. aureus.

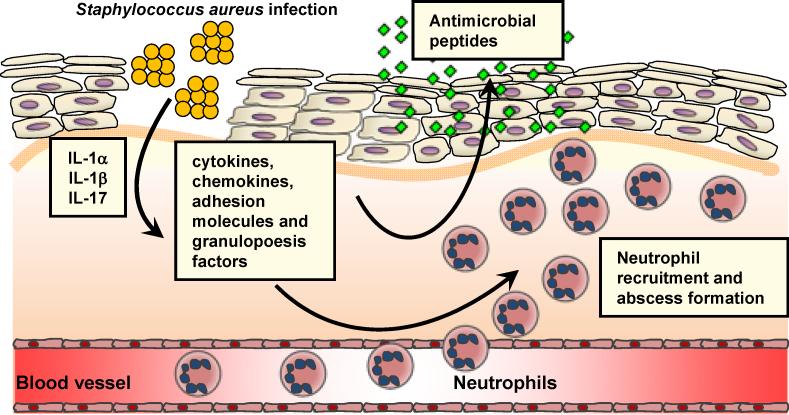

Neutrophil recruitment to the site of S. aureus infection in the skin is a hallmark of S. aureus infections and is required for bacterial clearance (Fig. 3) [33;34]. In a mouse model of S. aureus cutaneous infection, mice deficient in IL-1R had impaired neutrophil recruitment to the site of infection in the skin [35]. IL-1R is activated by its ligands IL-1α and IL-1β [8;9]. By investigating mice deficient in IL-1α or IL-1β, it was found that both IL-1α and IL-1β contributed to host defense against a superficial S. aureus skin infection whereas IL-1β largely mediated host defense during a deeper intradermal S. aureus infection [36]. These data suggest that both IL-1α and IL-1β contribute to host defense against a superficial S. aureus skin infections such as impetigo or an infected abrasions whereas IL-1β plays a predominant host defense role against deeper S. aureus skin infection such as cellulitis, folliculitis, subcutaneous abscesses and infected ulcers/wounds. This compartmentalization of IL-1α and IL-1β in the cutaneous immune response against S. aureus is likely the result of differential expression of these cytokines. Pre-made stores of IL-1α are released from keratinocytes in response to an infection and induces keratinocytes to produce neutrophil chemokines, such as CXCL1, CXCL2 and IL-8 [37]. In contrast, IL-1β is induced by many different cell types during an infection in the skin [8;9]. Furthermore, IL-1β release during a S. aureus skin infection requires activation of the inflammasome, an intracellular complex of proteins that triggers caspase-1-dependent cleavage of pro-IL-1β into its active form [38]. In this context, inflammasome activation has been shown to be mediated by S. aureus toxins such as α, β, and γ hemolysins and lysozyme digestion of S. aureus peptidoglycan [39;40]. Finally, human patients with defects in signaling molecules downstream of IL-1R and TLR family members (MyD88 and IRAK-4) where found to be highly susceptible to S. aureus cutaneous infections [41;42], suggesting an important role for the IL-1R signaling pathway in host defense against S. aureus skin infections in humans.

Figure 3. IL-1-mediated and IL17-mediated cutaneous immune response against S. aureus.

S. aureus infection of skin results in production of IL-1α, IL-1β and IL-17. These proinflammatory cytokines induce keratinocyte production of antimicrobial peptides (e.g. β-defensins 2 and 3, cathelicidin, RNase 7) and cytokines, chemokines, adhesion molecules and granulopoesis factors that promote neutrophil recruitment. Recruited neutrophils from the circulation form an abscess that helps control and limit the spread of infection, which is ultimately required for bacterial clearance.

In addition to IL-1, recent studies have uncovered a critical role for IL-17 in neutrophil recruitment and host defense against cutaneous S. aureus infections (Fig. 3). IL-17, which is predominantly produced by T cell subsets (such as Th17 cells, NKT cells and γδ T cells) and NK cells, has been known to induce neutrophil recruitment via induction of neutrophil chemokines (CXCL1, CXCL2 and IL-8) and granulopoesis factors (G-CSF and GM-CSF) [43;44]. Mice deficient in the two major forms of IL-17, IL-17A and IL-17F, were found to develop spontaneous S. aureus cutaneous abscesses [45]. Furthermore, mice deficient in the IL-17 receptor (IL-17RA) or mice treated with an anti-IL-17 neutralizing antibody had impaired clearance of a S. aureus cutaneous infection [46]. In this mouse model, γδ T cells in mouse skin were responsible for IL-17 production [46]. In humans, patients with hyper-IgE syndrome, who suffer from recurrent and severe S. aureus skin infections, possess STAT3 mutations that render them deficient in Th17 cells [47]. These findings in mice and humans provide evidence of an important role for IL-17 in host defense against cutaneous S. aureus infections.

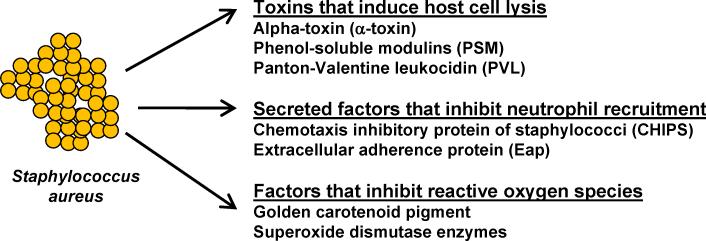

S. aureus virulence factors that promote infection

During an infection, S. aureus has several mechanisms to kill host immune cells and inhibit neutrophil recruitment and antimicrobial function (Fig. 4) [48;49]. There are pore-forming toxins of S. aureus that have the capacity to lyse host cells, including (1) the single-component α-hemolysin (or α-toxin) and (2) biocomponent leukotoxins, including γ-hemolysin, Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL), leukocidin E/D, and leukocidin M/F-PV-like [48]. Although PVL had initially been epidemiologically linked with CA-MRSA cutaneous infections, α-toxin and phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) are key S. aureus factors that contribute to the enhanced virulence of CA-MRSA skin infections [49;50]. In addition to inducing lysis of host cells, S. aureus inhibits neutrophil recruitment by the secretion of chemotaxis inhibitory protein of staphylococci (CHIPS), which interacts with the CD5aR and the formyl peptide receptor (FPR) [48] and extracellular adherence protein (Eap), which reduces endothelial expression of ICAM-1 [51]. S. aureus also produces factors that inhibit reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated killing by neutrophils, such as the golden carotenoid pigment of S. aureus and superoxide dismutase enzymes [52;53]. Taken together, S. aureus is well-equipped with several evasion mechanisms to block essential immune-mediated functions during an infection.

Figure 4. S. aureus virulence factors during cutaneous infection.

S. aureus secretes several virulence factors that evade host immune defenses. α-hemolysin (or α-toxin), phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs) and Panton-Valentine leukocidin (PVL) have the capacity to lyse host cells, which is a mechanism to evade immune responses. In addition, S. aureus secretes factors that inhibit neutrophil function such as chemotaxis inhibitory protein of staphylococci (CHIPS) extracellular adherence protein (Eap). Finally, S. aureus possesses factors that inhibit reactive oxygen species (ROS)-mediated killing by neutrophils such as the golden carotenoid pigment of S. aureus and superoxide dismutase enzymes.

Conclusion

In summary, the architecture of the skin provides unique interactions between the host and S. aureus. The cutaneous host defense mechanisms that protect against colonization include the epidermal barrier, commensal microorganisms and antimicrobial peptides. During an infection, cells in the epidermis and dermis recognize the pathogen and elicit early innate immune responses, including the recruitment of neutrophils from the circulation. On the other hand, S. aureus possesses numerous factors that promote adherence to the skin, evade neutrophil recruitment and function and inhibit immune responses. It is important to understand these host-pathogen interactions for the development of future vaccines and other immune-based therapeutic strategies.

Highlights.

S. aureus is a major cause of skin and soft tissue infections.

Commensal organisms and antimicrobial peptides protect against S. aureus skin colonization.

Neutrophil recruitment to the skin promotes bacterial clearance.

S. aureus possesses virulence factors that contribute to skin colonization and infection.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grant R01 AI 078910 (to L.S.M.) from the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- 1.McCaig LF, McDonald LC, Mandal S, Jernigan DB. Staphylococcus aureus-associated skin and soft tissue infections in ambulatory care. Emerg.Infect.Dis. 2006;12:1715–1723. doi: 10.3201/eid1211.060190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moran GJ, Krishnadasan A, Gorwitz RJ, Fosheim GE, McDougal LK, Carey RB, Talan DA. Methicillin-resistant S. aureus infections among patients in the emergency department. N.Engl.J.Med. 2006;355:666–674. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa055356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daum RS. Clinical practice. Skin and soft-tissue infections caused by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. N.Engl.J.Med. 2007;357:380–390. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp070747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deleo FR, Otto M, Kreiswirth BN, Chambers HF. Community-associated meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Lancet. 2010;375:1557–1568. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)61999-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Elston DM. Community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. J.Am.Acad.Dermatol. 2007;56:1–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorwitz RJ, Kruszon-Moran D, McAllister SK, McQuillan G, McDougal LK, Fosheim GE, Jensen BJ, Killgore G, Tenover FC, Kuehnert MJ. Changes in the prevalence of nasal colonization with Staphylococcus aureus in the United States, 2001-2004. J.Infect.Dis. 2008197:1226–1234. doi: 10.1086/533494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller LG, Diep BA. Clinical practice: colonization, fomites, and virulence: rethinking the pathogenesis of community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus infection. Clin.Infect.Dis. 2008;46:752–760. doi: 10.1086/526773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kupper TS, Fuhlbrigge RC. Immune surveillance in the skin: mechanisms and clinical consequences. Nat.Rev.Immunol. 2004;4:211–222. doi: 10.1038/nri1310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nestle FO, Di MP, Qin JZ, Nickoloff BJ. Skin immune sentinels in health and disease. Nat.Rev.Immunol. 2009;9:679–691. doi: 10.1038/nri2622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **10.Grice EA, Kong HH, Conlan S, Deming CB, Davis J, Young AC, Bouffard GG, Blakesley RW, Murray PR, Green ED, Turner ML, Segre JA. Topographical and temporal diversity of the human skin microbiome. Science. 2009;324:1190–1192. doi: 10.1126/science.1171700. [Using 16S ribosomal RNA bacterial gene sequencing, the authors demonstrate the diversity of bacterial organisms that are found on distinct sites of human skin. This landmark study was the first study to begin to decipher the microbiome of human skin.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grice EA, Segre JA. The skin microbiome. Nat.Rev.Microbiol. 2011;9:244–253. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miajlovic H, Fallon PG, Irvine AD, Foster TJ. Effect of filaggrin breakdown products on growth of and protein expression by Staphylococcus aureus. J.Allergy Clin.Immunol. 2010;126:1184–1190. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **13.Iwase T, Uehara Y, Shinji H, Tajima A, Seo H, Takada K, Agata T, Mizunoe Y. Staphylococcus epidermidis Esp inhibits Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and nasal colonization. Nature. 2010;465:346–349. doi: 10.1038/nature09074. [The authors showed that the serine protease Esp, which is secreted by the commensal skin bacterium S. epidermidis, inhibits colonization of S. aureus by inhibiting S. aureus biofilm formation and destroying pre-existing S. aureus biofilms. They further demonstrated that Esp-secreting S. epidermidis can eliminate S. aureus nasal colonization in humans in vivo. This study provided a novel mechanism and a potential therapeutic target to inhibit S. aureus colonization.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *14.Cogen AL, Yamasaki K, Sanchez KM, Dorschner RA, Lai Y, Macleod DT, Torpey JW, Otto M, Nizet V, Kim JE, Gallo RL. Selective antimicrobial action is provided by phenol-soluble modulins derived from Staphylococcus epidermidis, a normal resident of the skin. J.Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:192–200. doi: 10.1038/jid.2009.243. [This study demonstrated that the commensal skin bacterium S. epidermidis can inhibit colonization by S. aureus by secreting phenol-soluble modulins (PSMs), which directly induced antimicrobial activty against S. aureus. The study uncovered the important role of PSMs produced by commensal bacteria to inhibit S. aureus colonization.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *15.Lai Y, Cogen AL, Radek KA, Park HJ, Macleod DT, Leichtle A, Ryan AF, Di NA, Gallo RL. Activation of TLR2 by a small molecule produced by Staphylococcus epidermidis increases antimicrobial defense against bacterial skin infections. J.Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2211–2221. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.123. [The authors demonstrated that a component produced by the commensal bacterium S. epidermidis activated TLR2 on human keratinocytes, which enhanced production of the antimicrobial peptides hBD2 and hBD3. The study thus indentified a mechanism by which commensal bacterial can engage host immune defenses to prevent colonization or infection of the skin by S. aureus.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wanke I, Steffen H, Christ C, Krismer B, Gotz F, Peschel A, Schaller M, Schittek B. Skin commensals amplify the innate immune response to pathogens by activation of distinct signaling pathways. J.Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:382–390. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braff MH, Zaiou M, Fierer J, Nizet V, Gallo RL. Keratinocyte production of cathelicidin provides direct activity against bacterial skin pathogens. Infect.Immun. 2005;73:6771–6781. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.10.6771-6781.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harder J, Bartels J, Christophers E, Schroder JM. A peptide antibiotic from human skin. Nature. 1997;387:861. doi: 10.1038/43088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kisich KO, Howell MD, Boguniewicz M, Heizer HR, Watson NU, Leung DY. The constitutive capacity of human keratinocytes to kill Staphylococcus aureus is dependent on beta-defensin 3. J.Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:2368–2380. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *20.Simanski M, Dressel S, Glaser R, Harder J. RNase 7 protects healthy skin from Staphylococcus aureus colonization. J.Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:2836–2838. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.217. [This study demonstrated that exposure of human skin to S. aureus resulted in increased release of the antimicrobial peptide RNase 7, which exhibited potent killing of S. aureus. Thus, induction of RNase 7 represents a mechanism by which human skin can resist colonization (and perhaps subsequent infection) by S. aureus.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ong PY, Ohtake T, Brandt C, Strickland I, Boguniewicz M, Ganz T, Gallo RL, Leung DY. Endogenous antimicrobial peptides and skin infections in atopic dermatitis. N Engl J Med. 2002;347:1151–1160. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Clarke SR, Brummell KJ, Horsburgh MJ, McDowell PW, Mohamad SA, Stapleton MR, Acevedo J, Read RC, Day NP, Peacock SJ, Mond JJ, Kokai-Kun JF, Foster SJ. Identification of in vivo-expressed antigens of Staphylococcus aureus and their use in vaccinations for protection against nasal carriage. J.Infect.Dis. 2006;193:1098–1108. doi: 10.1086/501471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Weidenmaier C, Kokai-Kun JF, Kristian SA, Chanturiya T, Kalbacher H, Gross M, Nicholson G, Neumeister B, Mond JJ, Peschel A. Role of teichoic acids in Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization, a major risk factor in nosocomial infections. Nat.Med. 2004;10:243–245. doi: 10.1038/nm991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Burian M, Rautenberg M, Kohler T, Fritz M, Krismer B, Unger C, Hoffmann WH, Peschel A, Wolz C, Goerke C. Temporal expression of adhesion factors and activity of global regulators during establishment of Staphylococcus aureus nasal colonization. J.Infect.Dis. 2010;201:1414–1421. doi: 10.1086/651619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cho SH, Strickland I, Boguniewicz M, Leung DY. Fibronectin and fibrinogen contribute to the enhanced binding of Staphylococcus aureus to atopic skin. J.Allergy Clin.Immunol. 2001;108:269–274. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.117455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cho SH, Strickland I, Tomkinson A, Fehringer AP, Gelfand EW, Leung DY. Preferential binding of Staphylococcus aureus to skin sites of Th2-mediated inflammation in a murine model. J.Invest Dermatol. 2001;116:658–663. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Laouini D, Kawamoto S, Yalcindag A, Bryce P, Mizoguchi E, Oettgen H, Geha RS. Epicutaneous sensitization with superantigen induces allergic skin inflammation. J.Allergy Clin.Immunol. 2003;112:981–987. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Clarke SR, Mohamed R, Bian L, Routh AF, Kokai-Kun JF, Mond JJ, Tarkowski A, Foster SJ. The Staphylococcus aureus surface protein IsdA mediates resistance to innate defenses of human skin. Cell Host.Microbe. 2007;1:199–212. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sieprawska-Lupa M, Mydel P, Krawczyk K, Wojcik K, Puklo M, Lupa B, Suder P, Silberring J, Reed M, Pohl J, Shafer W, McAleese F, Foster T, Travis J, Potempa J. Degradation of human antimicrobial peptide LL-37 by Staphylococcus aureus-derived proteinases. Antimicrob.Agents Chemother. 2004;48:4673–4679. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.12.4673-4679.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller LS. Toll-like receptors in skin. Adv.Dermatol. 2008;24:71–87. doi: 10.1016/j.yadr.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **31.Hruz P, Zinkernagel AS, Jenikova G, Botwin GJ, Hugot JP, Karin M, Nizet V, Eckmann L. NOD2 contributes to cutaneous defense against Staphylococcus aureus through alpha-toxin-dependent innate immune activation. Proc.Natl.Acad.Sci.U.S.A. 2009;106:12873–12878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0904958106. [This study was the first study to demonstrate that NOD2, a cytoplasmic pattern recognition receptor that recognizes muramyl-dipeptide, a breakdown product of S. aureus peptidoglycan, plays an important role against S. aureus skin infections. The authors found that NOD2-deficient mice developed larger lesions with impaired bacterial clearance during a S. aureus skin infection. They further showed that S. aureus alpha-toxin was required for NOD2 activation, which induced IL-1β-mediated production of IL-6 to increase neutrophil killing of S. aureus.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Takeuchi O, Akira S. Pattern recognition receptors and inflammation. Cell. 2010;140:805–820. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **33.Kim MH, Granick JL, Kwok C, Walker NJ, Borjesson DL, Curry FR, Miller LS, Simon SI. Neutrophil survival and c-kit+-progenitor proliferation in Staphylococcus aureus-infected skin wounds promote resolution. Blood. 2011;117:3343–3352. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-07-296970. [Neutrophil recruitment from the circulation to form an abscess at the site of a S. aureus infection in the skin is required for bacterial clearance. This key study found that in addition to neutrophil recruitment, two novel mechanisms also contributed to maintenance of the neutrophil abscess: (1) increased neutrophil survival within the abscess and (2) production of mature neutrophils from c-kit+ progenitors at the site of infection in the skin.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Molne L, Verdrengh M, Tarkowski A. Role of neutrophil leukocytes in cutaneous infection caused by Staphylococcus aureus. Infect.Immun. 2000;68:6162–6167. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.11.6162-6167.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Miller LS, O'Connell RM, Gutierrez MA, Pietras EM, Shahangian A, Gross CE, Thirumala A, Cheung AL, Cheng G, Modlin RL. MyD88 mediates neutrophil recruitment initiated by IL-1R but not TLR2 activation in immunity against Staphylococcus aureus. Immunity. 2006;24:79–91. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *36.Cho JS, Zussman J, Donegan NP, Ramos RI, Garcia NC, Uslan DZ, Iwakura Y, Simon SI, Cheung AL, Modlin RL, Kim J, Miller LS. Noninvasive In Vivo Imaging to Evaluate Immune Responses and Antimicrobial Therapy against Staphylococcus aureus and USA300 MRSA Skin Infections. J.Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:907–915. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.417. [Using mice deficient in IL-1α or IL-1β, our laboratory found that both IL-1α and IL-1β contributed to host defense against a superficial S. aureus skin infection whereas IL-1β largely mediated host defense during a deeper intradermal S. aureus infection. Thus, differential host defense activity of IL-1α and IL-1β is dependent upon the depth of infection in the skin.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Olaru F, Jensen LE. Staphylococcus aureus stimulates neutrophil targeting chemokine expression in keratinocytes through an autocrine IL-1α signaling loop. J.Invest Dermatol. 2010;130:1866–1876. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Miller LS, Pietras EM, Uricchio LH, Hirano K, Rao S, Lin H, O'Connell RM, Iwakura Y, Cheung AL, Cheng G, Modlin RL. Inflammasome-Mediated Production of IL-1β Is Required for Neutrophil Recruitment against Staphylococcus aureus In Vivo. J.Immunol. 2007;179:6933–6942. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.10.6933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Munoz-Planillo R, Franchi L, Miller LS, Nunez G. A critical role for hemolysins and bacterial lipoproteins in Staphylococcus aureus-induced activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome. J.Immunol. 2009;183:3942–3948. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **40.Shimada T, Park BG, Wolf AJ, Brikos C, Goodridge HS, Becker CA, Reyes CN, Miao EA, Aderem A, Gotz F, Liu GY, Underhill DM. Staphylococcus aureus evades lysozyme-based peptidoglycan digestion that links phagocytosis, inflammasome activation, and IL-1beta secretion. Cell Host.Microbe. 2010;7:38–49. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2009.12.008. [The authors found that activation of the inflammasome, which is required to induce capase-1-mediated cleavage of pro-IL-1β into its active IL-1β, involves lysozyme digestion of S. aureus peptidoglycan. However, S. aureus chemically modifies its peptidoglycan to resist lysozyme digestion, thereby providing a novel immune evasion mechanism to prevent IL-1β-mediated host defense.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Picard C, Puel A, Bonnet M, Ku CL, Bustamante J, Yang K, Soudais C, Dupuis S, Feinberg J, Fieschi C, Elbim C, Hitchcock R, Lammas D, Davies G, Al-Ghonaium A, Al-Rayes H, Al-Jumaah S, Al-Hajjar S, Al-Mohsen IZ, Frayha HH, Rucker R, Hawn TR, Aderem A, Tufenkeji H, Haraguchi S, Day NK, Good RA, Gougerot-Pocidalo MA, Ozinsky A, Casanova JL. Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with IRAK-4 deficiency. Science. 2003;299:2076–2079. doi: 10.1126/science.1081902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.von Bernuth H, Picard C, Jin Z, Pankla R, Xiao H, Ku CL, Chrabieh M, Mustapha IB, Ghandil P, Camcioglu Y, Vasconcelos J, Sirvent N, Guedes M, Vitor AB, Herrero-Mata MJ, Arostegui JI, Rodrigo C, Alsina L, Ruiz-Ortiz E, Juan M, Fortuny C, Yague J, Anton J, Pascal M, Chang HH, Janniere L, Rose Y, Garty BZ, Chapel H, Issekutz A, Marodi L, Rodriguez-Gallego C, Banchereau J, Abel L, Li X, Chaussabel D, Puel A, Casanova JL. Pyogenic bacterial infections in humans with MyD88 deficiency. Science. 2008;321:691–696. doi: 10.1126/science.1158298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cua DJ, Tato CM. Innate IL-17-producing cells: the sentinels of the immune system. Nat.Rev.Immunol. 2010;10:479–489. doi: 10.1038/nri2800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Korn T, Bettelli E, Oukka M, Kuchroo VK. IL-17 and Th17 Cells. Annu.Rev.Immunol. 2009;27:485–517. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.021908.132710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **45.Ishigame H, Kakuta S, Nagai T, Kadoki M, Nambu A, Komiyama Y, Fujikado N, Tanahashi Y, Akitsu A, Kotaki H, Sudo K, Nakae S, Sasakawa C, Iwakura Y. Differential roles of interleukin-17A and -17F in host defense against mucoepithelial bacterial infection and allergic responses. Immunity. 2009;30:108–119. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.11.009. [This important study found that mice deficient in both IL-17A and IL-17F developed spontaneous S. aureus skin infections. Thus, this study directly implicated IL-17 responses in host defense against S. aureus skin infections.] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cho JS, Pietras EM, Garcia NC, Ramos RI, Farzam DM, Monroe HR, Magorien JE, Blauvelt A, Kolls JK, Cheung AL, Cheng G, Modlin RL, Miller LS. IL-17 is essential for host defense against cutaneous Staphylococcus aureus infection in mice. J.Clin.Invest. 2010;120:1762–1773. doi: 10.1172/JCI40891. [Our laboratory found that γδ T cells in mouse skin played an important role in host defense against a S. aureus skin infection by producing IL-17, which promoted neutrophil recruitment and bacterial clearance. The mechanism of IL-17 production during a S. aureus skin infection in vivo required IL-1, TLR2 and IL-23. Furthermore, the critical role for IL-17 in host defense against S. aureus skin infections was confirmed since mice deficient in IL-17R and mice treated with an anti-IL-17A blocking antibody had larger skin lesions and impaired bacterial clearance.] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Milner JD, Brenchley JM, Laurence A, Freeman AF, Hill BJ, Elias KM, Kanno Y, Spalding C, Elloumi HZ, Paulson ML, Davis J, Hsu A, Asher AI, O'Shea J, Holland SM, Paul WE, Douek DC. Impaired T(H)17 cell differentiation in subjects with autosomal dominant hyper-IgE syndrome. Nature. 2008;452:773–776. doi: 10.1038/nature06764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Foster TJ. Immune evasion by staphylococci. Nat.Rev.Microbiol. 2005;3:948–958. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Otto M. Basis of virulence in community-associated methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Annu.Rev.Microbiol. 2010;64:143–162. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.112408.134309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang R, Braughton KR, Kretschmer D, Bach TH, Queck SY, Li M, Kennedy AD, Dorward DW, Klebanoff SJ, Peschel A, Deleo FR, Otto M. Identification of novel cytolytic peptides as key virulence determinants for community-associated MRSA. Nat.Med. 2007;13:1510–1514. doi: 10.1038/nm1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Athanasopoulos AN, Economopoulou M, Orlova VV, Sobke A, Schneider D, Weber H, Augustin HG, Eming SA, Schubert U, Linn T, Nawroth PP, Hussain M, Hammes HP, Herrmann M, Preissner KT, Chavakis T. The extracellular adherence protein (Eap) of Staphylococcus aureus inhibits wound healing by interfering with host defense and repair mechanisms. Blood. 2006;107:2720–2727. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-08-3140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Karavolos MH, Horsburgh MJ, Ingham E, Foster SJ. Role and regulation of the superoxide dismutases of Staphylococcus aureus. Microbiology. 2003;149:2749–2758. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liu GY, Essex A, Buchanan JT, Datta V, Hoffman HM, Bastian JF, Fierer J, Nizet V. Staphylococcus aureus golden pigment impairs neutrophil killing and promotes virulence through its antioxidant activity. J.Exp.Med. 2005;202:209–215. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]