Abstract

Purpose

Studies treating adenocarcinoma of the pancreas with gemcitabine alone or in combination with a doublet have demonstrated modest improvements in survival. Recent reports have suggested that using the triple-drug regimen FOLFIRINOX can substantially extend survival in patients with metastatic disease. We were interested in determining the clinical benefit of another three-drug regimen of gemcitabine, docetaxel and capecitabine (GTX) in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma.

Patients and methods

The cases of 154 patients, who received treatment with GTX chemotherapy with histologically confirmed locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma, were retrospectively reviewed. All demographic and clinical data were captured including prior therapy, adverse events, treatment response and survival.

Results

One hundred and seventeen metastatic and 37 locally advanced cases of adenocarcinoma of the pancreas were reviewed. Partial responses were noted in 11% of cases, and stable disease was observed in 62% of patients. Responses significantly correlated with toxicity (neutropenia, ALT elevation and hospitalizations). Grade 3 or greater hematologic and non-hematologic toxicities were noted in 41% and 9% of cases, respectively. Overall median survival was 11.6 months. Chemotherapy naïve patients with metastatic and locally advanced disease achieved a median survival of 11.3 and 25.0 months, respectively.

Conclusions

We observe a substantial survival benefit with GTX chemotherapy in our cohort of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. These findings warrant further investigation of this combination in this patient population.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1007/s00280-011-1704-y) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Pancreatic cancer, Chemotherapy, Toxicity, Survival

Introduction

Since 1997, single-agent gemcitabine has been the standard of care for advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreas and the barometer by which all new therapies are measured [1]. The median overall survival (mOS) of single gemcitabine is approximately 6 months with a response rate of 10% in chemotherapy naïve patients with metastatic disease [1]. At least eight different agents have been evaluated in phase III studies in combination with gemcitabine, including irinotecan, oxaliplatin, cisplatin, docetaxel, erlotinib, bevacizumab and cetuximab [2–12]. None have shown any appreciable survival benefit, except for gemcitabine and erlotinib, which showed a small but significant benefit over gemcitabine alone in patients with metastatic disease [8].

More recently, there has been increased interest, in the use of triple-drug regimens in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. The combination of biweekly administered fluorouracil, irinotecan and oxaliplatin in a regimen termed FOLFIRINOX was studied in a phase III trial and was compared with gemcitabine as first-line treatment of metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma (n = 342). The FOLFIRINOX arm achieved a response rate of 31.6% and a mOS of 11.1 months [13].

Another three-drug regimen of interest is a combination that relies on synergy between gemcitabine, capecitabine and docetaxel (GTX), [14]. Optimized by Fine and colleagues, a prospective phase II study demonstrated response rates of 21.9% and a mOS of 14.5 months (n = 43) in advanced metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma [15]. Given the accessibility of GTX, many oncologists are now using this regimen on a routine basis. However, the overall benefit of GTX regimen is not fully understood, especially with the potential for greater toxicity.

Our institutions and others have noted improvements in disease control and survival with GTX in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. To evaluate the clinical benefit of this regimen, we compiled a large cohort of patients with locally advanced and metastatic disease treated at three different institutions with the GTX regimen and report the observations from this analysis.

Patients and methods

Patient eligibility

Patients with cytologically or histologically confirmed adenocarcinoma of the pancreas who received GTX regimen at Johns Hopkins Hospital, US Oncology—Dallas and Memorial Sloan Kettering Comprehensive Cancer Center, were included in this study. The retrospective review study was approved by the IRB at each institution. Data were collected by chart review of the patient’s medical records using a uniform database format. All data were de-identified prior to analysis.

Treatment regimen

The treatment included gemcitabine, docetaxel and capecitabine (GTX) as proposed by Fine and colleagues: capecitabine 750 mg/m2/day orally divided into two doses, days 1–14; intravenous (IV) gemcitabine 750 mg/m2 over 75 min on days 4 and 11 and docetaxel 30 mg/m2 IV on days 4 and 11. The cycles were repeated every 21 days. Chemotherapy was continued until disease progression, unacceptable toxicity or patient intolerance.

Evaluation of tumor response

CT scans were reviewed in response to treatment after 2–3 cycles of therapy with GTX using the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST). Complete response (CR) was defined as disappearance of all target lesions. Partial response (PR) was defined by at least 30% decrease in the tumor load, estimated by the sum of the diameters of target lesions. Progressive disease (PD) was defined as an increase of at least 20% in the sum of the diameters of target lesions. Stable disease (SD) was defined as disease that showed neither sufficient shrinkage nor increase to qualify as either PR or PD.

Evaluation of toxicities

Any episodes of chemotherapy-associated hematologic toxicities such as anemia, thrombocytopenia or leukopenia were graded according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria 4.0 (NCI CTC v4.0). Non-hematologic toxicities such as elevated AST and bilirubin were also assessed. Non-hematological toxicities that resulted in dose modifications were also collected. Toxicities were assessed for all cycles of GTX delivered. The number of hospitalizations during GTX treatment, regardless of cause, was recorded.

Statistical analysis

The overall study objective was to evaluate the efficacy and survival outcomes of a large unselected patient population treated with GTX regimen. Statistical analysis was coordinated by biostatisticians at Johns Hopkins Hospital. Characteristics of patients were descriptively compared between institutions using Wilcoxon rank sum tests or Fisher’s exact tests. The frequencies of grade 3/4 toxicities and partial responses, as measured using RECIST criteria, were compared between disease stages, grades and other characteristics with odds ratios that adjusted for patient age, sex, race and institution.

Overall survival was calculated from the time of GTX initiation until death. Patients who were alive at the time of analysis were censored at the date of last observation. Survival curves were plotted by the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate Cox proportional hazard models were used to assess whether any clinical predictors were independently associated with survival, response or severe grades 3–4 toxicity. All P values are based on two-tailed tests, and P = 0.05 was considered statistically significant. The following variables were assessed: age, performance, number of previous lines of therapy and number of comorbidities.

Results

Patient characteristics

Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1. From May 2003 to March 2010, a total of 154 patients received GTX. Ninety-four percent of the treated patients received treatment after 2006. At the time of GTX administration, 37 patients had radiographically confirmed locally advanced disease and 117 had confirmed evidence of metastatic disease. (Twenty of the 37 patients with locally advanced disease had a prior history of radiation therapy.) Records were obtained from three medical centers: Johns Hopkins Hospital, Memorial Sloan Kettering Comprehensive Cancer Center and US Oncology—Dallas (Table S1).

Table 1.

Patients’ Characteristics

| All patients N = 154 |

|

|---|---|

| Age—median (range) | 62 (37, 83) |

| Gender—no. (%) | |

| Male | 86 (56) |

| Female | 68 (44) |

| Race—no. (%) | |

| African American | 12 (9) |

| Caucasian | 120 (86) |

| Hispanic | 3 (2) |

| Asian | 5 (4) |

| Missing | 14 |

| Stage—no. (%) | |

| Locally advanced | 37 (24) |

| Metastatic | 117 (76) |

| Grade—no. (%) | |

| Well-differentiated | 3 (2) |

| Moderately differentiated | 31 (20) |

| Poorly differentiated | 15 (10) |

| Unknown | 105 (68) |

| ECOG—no. (%) | |

| 0 | 44 (29) |

| 1 | 100 (66) |

| 2 | 7 (5) |

| Missing | 3 |

| Number of comorbidities—median (range) | 2 (0, 8) |

| Family history of cancer—no. (%) | |

| Yes | 115 (77) |

| No | 35 (23) |

| Missing | 4 |

| Family history of pancreas cancer—no. (%) | |

| Yes | 7 (10) |

| No | 65 (90) |

| Missing | 82 |

| Number of cycles—median (range) | 4 (1, 40) |

| Number of metastatic sites—no. (%) | |

| 0 | 22 (29) |

| 1 | 33 (43) |

| 2 | 16 (21) |

| 3 | 5 (7) |

| Missing | 78 |

| Prior chemotherapy—no. (%) | |

| No | 79 (51) |

| Yes | 75 (49) |

| Previous surgery—no. (%) | |

| Yes | 16 (21) |

| No | 61 (79) |

| Missing | 77 |

| Line of GTX therapy—no. (%) | |

| First | 79 (51) |

| Second or greater | 75 (49) |

| Ascites—no. (%) | |

| Yes | 25 (16) |

| No | 129 (84) |

The median age of the patients reviewed was 62 years. The majority of patients was metastatic (77%) and had an ECOG performance status (ECOG PS) of 1 (66%). GTX was the first regimen attempted for 51% of cases reviewed, and the average number of cycles completed was 4. Twenty-one percent of patients had prior surgery with curative intent prior to initiating GTX therapy. None of the patients received GTX in the adjuvant setting.

Toxicities

Hematological and non-hematological toxicities were assessed in all treated patients (n = 154) and are shown in Table 2. No GTX-related deaths were noted. Hospitalization data were available on 50% of patients, of which 33% required at least one inpatient hospitalization while receiving GTX. Nine percent of patients experienced grade 3/4 non-hematological toxicity, and 41% experienced hematological toxicity. Grade 3/4 anemia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia occurred in 12%, 34% and 13% of patients, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Frequency of toxicities, overall and by staging

| All patients N = 154 |

LAPC N = 37 |

Mets, first line N = 50 |

Mets, second + line N = 67 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any grade 3/4 hematological toxicity—no. (%) | |||||

| No | 90 (59) | 17 (47) | 35 (70) | 38 (58) | 0.1 |

| Yes | 62 (41) | 19 (53) | 15 (30) | 28 (42) | |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Thrombocytopenia—no. (%) | |||||

| Grade 1/2 | 80 (68) | 21 (68) | 25 (66) | 34 (69) | 0.279 |

| Grade 3/4 | 15 (13) | 5 (16) | 2 (5) | 8 (16) | |

| None | 23 (19) | 5 (16) | 11 (29) | 7 (14) | |

| Missing | 36 | 6 | 12 | 18 | |

| Neutropenia—no. (%) | |||||

| Grade 1/2 | 41 (36) | 13 (41) | 10 (25) | 18 (43) | 0.185 |

| Grade 3/4 | 39 (34) | 13 (41) | 13 (32) | 13 (31) | |

| None | 34 (30) | 6 (19) | 17 (42) | 11 (26) | |

| Missing | 40 | 5 | 10 | 25 | |

| Leucopenia—no. (%) | |||||

| Grade 1/2 | 69 (57) | 19 (59) | 22 (54) | 28 (60) | 0.32 |

| Grade 3/4 | 35 (29) | 9 (28) | 10 (24) | 16 (34) | |

| None | 16 (13) | 4 (12) | 9 (22) | 3 (6) | |

| Missing | 34 | 5 | 9 | 20 | |

| Anemia—no. (%) | |||||

| Grade 1/2 | 129 (85) | 30 (83) | 46 (92) | 53 (80) | 0.125 |

| Grade 3/4 | 19 (12) | 5 (14) | 2 (4) | 12 (18) | |

| None | 4 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (4) | 1 (2) | |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Any grade 3/4 non-hematological toxicity—no. (%) | |||||

| No | 138 (91) | 30 (86) | 48 (96) | 60 (91) | 0.235 |

| Yes | 13 (9) | 5 (14) | 2 (4) | 6 (9) | |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Elevated ALT—no. (%) | |||||

| Grade 1/2 | 75 (50) | 18 (51) | 33 (66) | 24 (36) | 0.008 |

| Grade 3/4 | 9 (6) | 4 (11) | 2 (4) | 3 (5) | |

| None | 67 (44) | 13 (37) | 15 (30) | 39 (59) | |

| Missing | 3 | 2 | 0 | 1 | |

| Bilirubin—no. (%) | |||||

| Grade 1/2 | 35 (35) | 8 (29) | 11 (32) | 16 (43) | 0.132 |

| Grade 3/4 | 5 (5) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 4 (11) | |

| None | 59 (60) | 19 (68) | 23 (68) | 17 (46) | |

| Missing | 55 | 9 | 16 | 30 | |

| Hospitalizations—no. (%) | |||||

| None | 51 (67) | 20 (74) | 17 (61) | 14 (67) | 0.617 |

| 1 or more | 25 (33) | 7 (26) | 11 (39) | 7 (33) | |

| Missing | 78 | 10 | 22 | 46 |

LAPC locally advanced pancreatic cancer

Grade 3/4 toxicity from GTX was found to be independent of treatment location (Table S3), stage, grade, ECOG PS, prior surgery, ascites or hospitalization (Table S3). Any prior chemotherapy minimally correlated with grade 3/4 toxicity (adjusted odds ratio (OR) 2.01, 95% CI 0.97–4.16, P = 0.057).

Dose reductions and chemotherapy modifications were evaluated in half of the patients (77/154). Hematological complications (myelosuppression) resulted in dose reduction in 34% of the patients (26/77). Non-hematological toxicities that resulted in dose modifications occurred in 30% of the patients (23/77). The reasons that resulted in GTX dose modifications included one or more of the following: fatigue (n = 4) anasarca (n = 2), decreased performance status (n = 2), diarrhea/mucositis (n = 12), intractable nausea/vomiting (n = 3), hand and foot syndrome (n = 2) or multiple procedures required (n = 1).

Response rates

One hundred and forty-six (95%) of the 154 cases were evaluable for response using RECIST criteria [16]. Assessments were performed after every 2–3 cycles of GTX chemotherapy. Partial responses were seen in 11% (n = 16) of patients. Stable disease was seen in 62% of cases (n = 91) and progressive disease in 27% (n = 39). No complete responses were observed. Response rates by extent of disease and line of therapy are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Response rates

| All patients N = 154 |

LAPC N = 37 |

Metastatic N = 117 |

P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RECIST—no. (%) | ||||

| Partial response | 16 (11) | 4 (11) | 12 (11) | 0.012 |

| Stable disease | 91 (62) | 28 (80) | 63 (57) | |

| Progressive disease | 39 (27) | 3 (9) | 36 (32) | |

| Missing | 8 | 2 | 6 | |

LAPC locally advanced pancreatic cancer

Elevated ALT, any neutropenia and hospitalization correlated strongly with achieving a partial response (adjusted OR 3.57, 95% CI 0.92–13.8, P = 0.045, ALT elevation; adjusted OR 5.10, 95% CI 0.9–28.91, P = 0.041, any neutropenia; adjusted OR 5.37, 95% CI 1.09–26.51, P = 0.032, hospitalization). A borderline significant correlation with improved response was noted in metastatic patients who received GTX as their first-line therapy (adjusted OR 2.56, 95% CI 0.62–10.59, P = 0.055). Prior chemotherapy negatively correlated with response (adjusted OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.03–0.83, P = 0.012). These findings are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Predictors of response

| SD or PD N = 130 |

PR N = 16 |

Adjusted OR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Stage—no. (%) | |||||

| Locally advanced | 31 (24) | 4 (25) | 1.00 | – | |

| Metastatic | 99 (76) | 12 (75) | 1.63 | (0.4, 6.65) | 0.484 |

| Stage/GTX—no. (%) | |||||

| Locally advanced | 31 (24) | 4 (25) | 1.00 | – | |

| Mets, first line | 38 (29) | 10 (62) | 2.56 | (0.62, 10.59) | 0.055 |

| Mets, second line | 61 (47) | 2 (12) | 0.44 | (0.06, 3.13) | |

| Grade—no. (%) | |||||

| Well or moderately differentiated | 28 (22) | 5 (31) | 1.00 | – | |

| Poorly differentiated or unknown | 102 (78) | 11 (69) | 0.51 | (0.15, 1.77) | 0.3 |

| ECOG—no. (%) | |||||

| 0 | 37 (29) | 6 (38) | 1.00 | – | |

| 1+ | 91 (71) | 10 (62) | 0.56 | (0.17, 1.83) | 0.341 |

| Prior chemotherapy—no. (%) | |||||

| No | 62 (48) | 14 (88) | 1.00 | – | |

| Yes | 68 (52) | 2 (12) | 0.16 | (0.03, 0.83) | 0.012 |

| Previous surgery—no. (%) | |||||

| Yes | 15 (25) | 1 (8) | 1.00 | – | |

| No | 46 (75) | 11 (92) | 1.44 | (0.14, 15.03) | 0.756 |

| Ascites—no. (%) | |||||

| Yes | 21 (16) | 1 (6) | 1.00 | – | |

| No | 109 (84) | 15 (94) | 5.83 | (0.59, 57.55) | 0.074 |

| Any grade 3/4 hematological toxicity—no. (%) | |||||

| No | 77 (60) | 8 (50) | 1.00 | – | |

| Yes | 51 (40) | 8 (50) | 1.27 | (0.41, 3.95) | 0.682 |

| Any grade 3/4 non-hematological toxicity—no. (%) | |||||

| No | 116 (91) | 16 (100) | 1.00 | – | |

| Yes | 11 (9) | 0 (0) | 0.00 | (0, Inf) | 0.103 |

| Thrombocytopenia—no. (%) | |||||

| None | 19 (20) | 4 (27) | 1.00 | – | |

| Any | 77 (80) | 11 (73) | 0.73 | (0.18, 2.96) | 0.667 |

| Neutropenia—no. (%) | |||||

| None | 29 (31) | 2 (14) | 1.00 | – | |

| Any | 65 (69) | 12 (86) | 5.10 | (0.9, 28.91) | 0.041 |

| Leucopenia—no. (%) | |||||

| None | 14 (14) | 1 (6) | 1.00 | – | |

| Any | 84 (86) | 15 (94) | 3.53 | (0.39, 31.83) | 0.203 |

| Anemia—no. (%) | |||||

| None | 4 (3) | 0 (0) | 1.00 | – | |

| Any | 124 (97) | 16 (100) | Inf | (0, Inf) | 0.43 |

| Elevated ALT—no. (%) | |||||

| None | 58 (46) | 4 (25) | 1.00 | – | |

| Any | 69 (54) | 12 (75) | 3.57 | (0.92, 13.8) | 0.045 |

| Bilirubin—no. (%) | |||||

| None | 45 (56) | 11 (92) | 1.00 | – | |

| Any | 36 (44) | 1 (8) | 0.26 | (0.02, 2.68) | 0.208 |

| Hospitalizations—no. (%) | |||||

| None | 42 (70) | 6 (50) | 1.00 | – | |

| 1 or more | 18 (30) | 6 (50) | 5.37 | (1.09, 26.51) | 0.032 |

| Change in CA19 from baseline | – | ||||

| <25% | 34 (36) | 4 (29) | 1.00 | – | |

| 25–50% | 24 (25) | 3 (21) | 1.81 | (0.29, 11.3) | |

| 50–75% | 18 (19) | 1 (7) | 0.46 | (0.04, 5.53) | |

| >75% | 19 (20) | 6 (43) | 4.79 | (0.88, 25.9) | 0.112 |

Adjusted odds ratios for the likelihood of achieving a PR

Tumor marker analysis

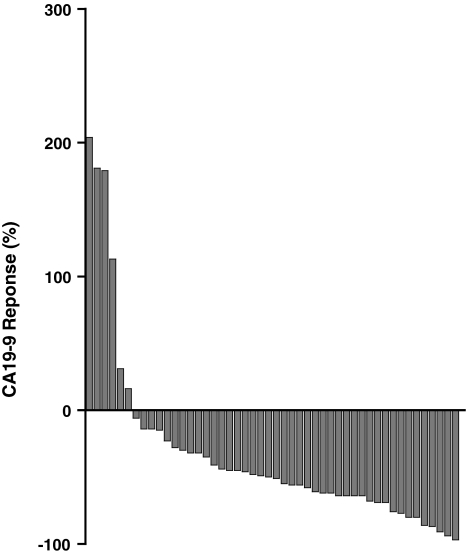

Longitudinal CA19-9 values for the first two cycles of therapy were available for 86 cases. Patients that did not express CA19-9 were excluded from the analysis. Seventy-seven percent (n = 66) of patients demonstrated a measurable decline in CA19-9 after two cycles of therapy with GTX. When GTX was used as first-line therapy (n = 48), a decline CA19-9 was observed in 91% of cases (Fig. 1). In the second line or greater (n = 38), the CA19-9 response was seen in 63% of cases.

Fig. 1.

Waterfall plot of the CA19-9 response in patients treated with first-line therapy with GTX

There was no correlation between CA19-9 response, objective radiographic response (Table 4) or survival when measured as a continuous variable (Figure S1). Even when CA19-9 responses were separated into groups using cutoffs defined by percent decline in CA19-9 levels or by line of therapy, there was no correlation with overall survival (Tables 5, S4).

Table 5.

Estimates of OS (time from start of GTX therapy to death) for patients who received their first line of GTX

| N | Median OS (months) | 1 year OS | HR | 95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All patients | 79 | 11.6 | 46 (34, 62) | |||

| All patients, by staging | ||||||

| LAPC | 29 | 25.03 | 56 (37, 84) | 1.00 | – | |

| Mets | 50 | 11.3 | 42 (28, 62) | 1.37 | (0.6, 3.13) | 0.461 |

| Grade | ||||||

| Well or moderately differentiated | 15 | 21.93 | 60 (36, 100) | 1.00 | – | |

| Poorly differentiated or unknown | 64 | 11.3 | 43 (30, 61) | 1.29 | (0.51, 3.27) | 0.595 |

| ECOG | ||||||

| 0 | 28 | 23.23 | 64 (44, 94) | 1.00 | – | |

| 1+ | 50 | 9.9 | 38 (25, 58) | 2.57 | (1.03, 6.41) | 0.043 |

| Prior surgery | ||||||

| Yes | 4 | 14.27 | 100 (100, 100) | 1.00 | – | |

| No | 44 | 9.9 | 42 (26, 69) | 0.84 | (0.08, 9.29) | 0.886 |

| Hospitalizations | ||||||

| None | 32 | 14.27 | 51 (31, 83) | 1.00 | – | |

| 1 or more | 15 | 11.3 | 44 (21, 89) | 0.84 | (0.22, 3.19) | 0.8 |

| Any grade 3/4 toxicity | ||||||

| No | 47 | 11.7 | 48 (33, 69) | 1.00 | – | |

| Yes | 31 | 9.9 | 41 (24, 70) | 1.03 | (0.5, 2.13) | 0.928 |

| Family history of cancer | ||||||

| No | 19 | 8.87 | 10 (2, 61) | 1.00 | – | |

| Yes | 57 | 14.27 | 59 (46, 76) | 0.61 | (0.27, 1.35) | 0.221 |

| Comorbidities | ||||||

| None | 10 | 14.27 | 86 (63, 100) | 1.00 | – | |

| 1 or more | 38 | 9.5 | 31 (15, 65) | 2.74 | (0.45, 16.56) | 0.273 |

| Neutropenia | ||||||

| No | 22 | 9.5 | 47 (26, 85) | 1.00 | – | |

| Yes | 42 | 12.13 | 52 (36, 74) | 1.00 | (0.39, 2.52) | 0.994 |

| Elevated ALT | ||||||

| No | 24 | 8.07 | 32 ((15, 69) | 1.00 | – | |

| Yes | 53 | 13.3 | 52 (38, 71) | 0.73 | (0.34, 1.56) | 0.42 |

| Change in CA19 from baseline | ||||||

| <25% | 20 | 7.97 | 39 (19, 76) | 1.00 | – | |

| 25–50% | 20 | 12.13 | 51 (31, 84) | 0.76 | (0.26, 2.22) | 0.582 |

| 50–75% | 13 | 9.03 | 25 (8, 83) | 1.19 | (0.38, 3.73) | |

| >75% | 12 | 13.3 | 62 (38, 100) | 0.56 | (0.18, 1.76) | |

| RECIST-based response | ||||||

| Partial response | 14 | 21.93 | 65 (42, 100) | 1.00 | – | |

| Stable disease | 50 | 12.13 | 51 (35, 73) | 2.03 | (0.7, 5.93) | |

| Progressive disease | 12 | 7.93 | 10 (2, 65) | 6.32 | (1.74, 22.9) | 0.017 |

| Missing | 3 | 4.6 | 33 (7, 100) |

Values are OS (95% CI)

LAPC locally advanced pancreatic cancer

Survival analysis

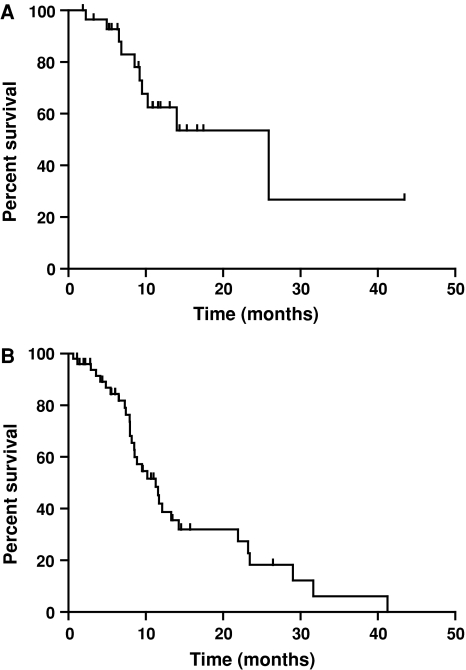

Chemotherapy naïve patients achieved a mOS of 11.6 months (n = 75) and a 1-year survival of 46% when treated with GTX. Patients who received first-line GTX with metastatic and locally advanced disease achieved a median survival of 11.3 and 25.0 months, respectively (Fig. 2). In the first-line setting, only ECOG PS correlated with improved survival (adjusted HR 2.57, 95% CI 1.03–6.41, P = 0.043) as shown in Table 5.

Fig. 2.

Kaplan–Meier estimates of patients treated with GTX as first-line therapy with a locally advanced and b metastatic pancreatic cancer

When GTX was used as second line or greater (n = 79), the mOS was 5.7 months and 1-year survival was 32% (Table S4). In patients with locally advanced disease, the mOS was 16.2 and 5.7 months in metastatic patients. Prior surgery with curative intent (adjusted HR 529.1, 95% CI 3.52–79,433.25, P = 0.014) strongly correlated with improved survival. In the second line setting, experiencing any grade 3/4 toxicity was a negative factor for survival (adjusted HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.25–0.9, P = 0.022).

In the first and second lines of therapy with GTX, there was a marked improvement in survival in patients who demonstrated a RECIST-based partial response (Table 5, Table S4).

Discussion

Advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma is a genetically complex disease that is uniformly lethal with annual incidence approaching its yearly mortality [17]. Much like other solid tumors, disease progression is most dependent on time as measured by the sequential accumulation of somatic mutations [18, 19]. Despite improvements in the treatment of other solid tumors, the use of combination chemotherapy or the introduction of novel targeted molecules has minimal objective benefit.

The failure of several phase III trials examining doublet chemotherapy in metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma prompted us to examine our use of the triplet, GTX. Originally reported by Fine and colleagues, this regimen combines relatively low doses of gemcitabine and docetaxel in synergy to augment the performance of capecitabine. GTX was optimized in pancreatic cancer cell lines, where capecitabine was sequenced 72–96 h before docetaxel and gemcitabine to achieve maximal tumor kill [14]. Initial human studies demonstrated prolonged survivals in good performance status patients [15].

Our data are consistent with the previous reports using GTX and other triple-drug regimens and beg the question whether more chemotherapy is better? A series of studies by Reni et al. utilizing four agents: cisplatin, epirubicin, fluorouracil and gemcitabine (PEFG) has been reported and showed a significant improvement in radiographic response that was accompanied by increases in grades 3–4 neutropenia and thrombocytopenia [20, 21]. Whether adding more agents is the best approach remains to be seen, but the primary concern for future adoption of any multiagent regimens appears to be the frequency of significant toxicity.

Interestingly, in our cohort, developing toxicities from GTX (any neutropenia, elevated ALT and hospitalizations) were markers for objective radiographic responses. This has been noted with both targeted and conventional chemotherapy regimens where systemic toxicity correlated with clinical response (e.g., skin rash to EGFR inhibitors) and suggests that germ line factors may dictate the sensitivity to this and other such regimens [22].

Perhaps, the most surprising finding is the 25-month survival seen in the first-line setting in patients with unresectable locally advanced disease, which exceeds the median survival in patients undergoing surgical resection [23, 24]. It is also more than twice the survival demonstrated in those patients with metastatic disease receiving first-line GTX. Given these findings, it is interesting to speculate that locally advanced and metastatic pancreatic cancer may represent two separate disease entities that may in part be differentiated by DPC4 expression [25]. An alternative explanation is that the locally advanced cases may represent a less genetically complex disease state, that is, therefore more susceptible to multiagent chemotherapy [19].

We were also surprised to find the CA19-9 response did not correlate with survival or response in this cohort of patients, even when examined as a continuous or discrete variable. While more than 75% of the cases reviewed demonstrate CA19-9 decline after two cycles, this did not correspond with a decline in tumor burden. Nonetheless, a fluctuation in the CA19-9 level does suggest that chemotherapy was reaching the tumor and altering CA19-9 production by tumor or adjacent cells.

In summary, GTX appears to be an active three-drug regimen in advanced adenocarcinoma of the pancreas, in particular, in those patients with therapy-associated toxicity. These findings further support future clinical investigation of multiagent regimens, such as GTX, in the treatment of pancreatic cancer.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Open Access

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Noncommercial License which permits any noncommercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author(s) and source are credited.

References

- 1.Burris HA, 3rd, Andersen J, et al. Improvements in survival and clinical benefit with gemcitabine as first-line therapy for patients with advanced pancreas cancer: a randomized trial. J Clin Oncol. 1997;15:2403–2413. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cunningham D, Chau I, Stocken DD, et al. Phase III randomized comparison of gemcitabine versus gemcitabine plus capecitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5513–5518. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.24.2446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dahan L, Bonnetain F, Ychou M, et al. Combination 5-fluorouracil, folinic acid and cisplatin (LV5FU2-CDDP) followed by gemcitabine or the reverse sequence in metastatic pancreatic cancer: final results of a randomised strategic phase III trial (FFCD 0301) Gut. 2010;59:1527–1534. doi: 10.1136/gut.2010.216135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Heinemann V, Quietzsch D, Gieseler F, et al. Randomized phase III trial of gemcitabine plus cisplatin compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3946–3952. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herrmann R, Bodoky G, Ruhstaller T, et al. Gemcitabine plus capecitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomized, multicenter, phase III trial of the swiss group for clinical cancer research and the central European cooperative oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:2212–2217. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.0886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kindler HL, Niedzwiecki D, Hollis D, et al. Gemcitabine plus bevacizumab compared with gemcitabine plus placebo in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: phase III trial of the cancer and leukemia group B (CALGB 80303) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3617–3622. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.28.1386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kulke MH, Tempero MA, Niedzwiecki D, et al. Randomized phase II study of gemcitabine administered at a fixed dose rate or in combination with cisplatin, docetaxel, or irinotecan in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer: CALGB 89904. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5506–5512. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.1309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moore MJ, Goldstein D, Hamm J, et al. Erlotinib plus gemcitabine compared with gemcitabine alone in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer: a phase III trial of the national cancer institute of Canada clinical trials group. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:1960–1966. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9525. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Philip PA, Benedetti J, Corless CL, et al. Phase III study comparing gemcitabine plus cetuximab versus gemcitabine in patients with advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: southwest oncology group-directed intergroup trial S0205. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3605–3610. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.7550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Poplin E, Feng Y, Berlin J, et al. Phase III, randomized study of gemcitabine and oxaliplatin versus gemcitabine (fixed-dose rate infusion) compared with gemcitabine (30-minute infusion) in patients with pancreatic carcinoma E6201: a trial of the eastern cooperative oncology group. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:3778–3785. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.9007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stathopoulos GP, Syrigos K, Aravantinos G, et al. A multicenter phase III trial comparing irinotecan-gemcitabine (IG) with gemcitabine (G) monotherapy as first-line treatment in patients with locally advanced or metastatic pancreatic cancer. Br J Cancer. 2006;95:587–592. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Van Cutsem E, Vervenne WL, Bennouna J, et al. Phase III trial of bevacizumab in combination with gemcitabine and erlotinib in patients with metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:2231–2237. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.20.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Conroy T, Desseigne F, Ychou M et al (2011) FOLFIRINOX versus gemcitabine for metastatic pancreatic cancer. N Engl J Med 364:1817–1825 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Fine RL, Fogelman DR, Schreibman SM, et al. The gemcitabine, docetaxel, and capecitabine (GTX) regimen for metastatic pancreatic cancer: a retrospective analysis. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2008;61:167–175. doi: 10.1007/s00280-007-0473-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fine RL, Moorer G, Sherman W et al (2009) Phase II trial of GTX chemotherapy in metastatic pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol 27(suppl; abstr 4623)

- 16.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–247. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, et al. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321:1801–1806. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yachida S, Jones S, Bozic I, et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1114–1117. doi: 10.1038/nature09515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reni M, Cereda S, Bonetto E, et al. Dose-intense PEFG (cisplatin, epirubicin, 5-fluorouracil, gemcitabine) in advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;59:361–367. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0277-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reni M, Cordio S, Milandri C, et al. Gemcitabine versus cisplatin, epirubicin, fluorouracil, and gemcitabine in advanced pancreatic cancer: a randomised controlled multicentre phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2005;6:369–376. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(05)70175-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wacker B, Nagrani T, Weinberg J, et al. Correlation between development of rash and efficacy in patients treated with the epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor erlotinib in two large phase III studies. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:3913–3921. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Laethem JL, Hammel P, Mornex F, et al. Adjuvant gemcitabine alone versus gemcitabine-based chemoradiotherapy after curative resection for pancreatic cancer: A randomized EORTC-40013–22012/FFCD-9203/GERCOR phase II study. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:4450–4456. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.3446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Bassi C, et al. Adjuvant chemotherapy with fluorouracil plus folinic acid vs gemcitabine following pancreatic cancer resection: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2010;304:1073–1081. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.1275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Iacobuzio-Donahue CA, Fu B, Yachida S, et al. DPC4 gene status of the primary carcinoma correlates with patterns of failure in patients with pancreatic cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:1806–1813. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.17.7188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.