Abstract

Background: The increasing concentration of populations into large conurbations in recent decades has not been matched by international health assessments, which remain largely focused at the country level. We aimed to demonstrate the use of routine survey data to compare the health of large metropolitan centres across Europe and determine the extent to which differences are due to socio-economic factors. Methods: Multilevel modelling of health survey data on 126 853 individuals from 33 metropolitan areas in the UK, Republic of Ireland, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Spain, Belgium and Germany compared general health, longstanding illness, acute sickness, psychological distress and obesity with the average for all areas, accounting for education and social class. Results: We found some areas (Greater Glasgow; Greater Manchester, Cheshire and Merseyside; Northumberland, Tyne and Wear and South Yorkshire) had significantly higher levels of poor health. Other areas (West Flanders and Antwerp) had better than average health. Differences in individual socio-economic circumstances did not explain findings. With a few exceptions, acute sickness levels did not vary. Conclusion: Health tended to be worse in metropolitan areas in the north and west of the UK and the central belt and south east of Germany, and more favourable in Sweden and north west Belgium, even accounting for socio-economic composition of local populations. This study demonstrated that combining national health survey data covering different areas is viable but not without technical difficulties. Future comparisons between European regions should be made using standardized sampling, recruitment and data collection protocols, allowing proper monitoring of health inequalities.

Introduction

It is known that population health varies across countries and continents. International comparisons provide external standards, help identify important determinants1 and inform frameworks for setting and monitoring public health goals. The European Commission aims to establish a broad cross-policy framework to respond to a wide range of health challenges,2 prompting a common initiative. In recent decades there has been an unprecedented concentration of populations into large conurbations and while metropolitan areas in Europe share many features such as high population density, environment and structural organization, their health may vary. Comparisons at this level could help us to understand local features in an international context, providing evidence for health promotion, prioritization and accountability at the local level.3

Apart from some studies which have generally had specific foci,4–7 most international assessments performed to date have been done on an ecological basis8,9 and have not been based on individual record data using harmonized methodologies. A few recent individual-based studies have made comparisons across European countries but only at national level.10–11 With few exceptions,12–13 studies with international coverage14–16 tend not to have big enough samples to permit comparisons at the sub-country level. There are several ongoing population-based health surveys covering metropolitan areas in Europe that share common design features, providing the opportunity to combine and compare data at this level. However, the validity of available data and practicalities for such comparisons have not been considered.

While international differences in health outcomes may suggest the existence of contextual determinants (such as distinct historical, societal and health care systems), it is possible they could be explained by variations in individual area composition in terms of socio-economic characteristics. To address this issue, we used the internationally harmonious measures of education and occupation-based social class.17–19

This aims of this study were to demonstrate the use of routine health survey data for comparing health outcome measures across 33 Europe metropolitan areas, and investigate the extent to which socio-economic circumstances might explain any differences. By combining data on almost 127 000 adults from individual surveys, our collaboration represents the step prior to the creation of a common European public health survey.20

Methods

Population health survey data

Analyses were based on data from 12 European health surveys in 11 countries covering Western, Northern and Southern Europe (table 1). These surveys were conducted during 2001–05, and responses ranged from 46% to 85%; the health data at the lower range of response level has been shown to be unbiased in terms of social inequality.21 Surveys interviews were conducted in person with the exceptions of Germany (telephone), the Republic of Ireland, Sweden and Finland (postal) and Wales (brief face-to-face interview with self-completion questionnaires). European capital cities and greater metropolitan areas with populations of more than 1 000 00022—or the closest proxy to these—were identified, with 33 such areas included.

Table 1.

European metropolitan areas and corresponding source survey data

| Metropolitan area | Survey area | Population (1000s)a | Men (56 853) | Women (69 080) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greater Glasgow | Greater Glasgowb,c | 1200 | 557 | 710 |

| Edinburgh | Lothianc | 800 | 473 | 605 |

| Greater London | North West/North Central/North East/South East/South West Londond | 7429 | 1763 | 2292 |

| Manchester-Liverpool | Greater Manchester, Cheshire and Merseysided | 2539 | 1357 | 1742 |

| West Midlands | Birmingham and the Black Country, West Midlands Southd | 3834 | 1005 | 1356 |

| West Yorkshire | West Yorkshired | 2108 | 580 | 778 |

| Tyne and Wear | Northumberland, Tyne and Weard | 1396 | 447 | 625 |

| Nottingham | Trentd | 2687 | 387 | 448 |

| South Yorkshire | South Yorkshired | 1278 | 485 | 608 |

| Portsmouth-Southampton | Hampshire and Isle of Wightd | 1801 | 843 | 1095 |

| Belfast | Eastern Northern Irelande | 1139 | 1887 | 2373 |

| Cardiff | Cardifff | 318 | 1012 | 1210 |

| Dublin | Dubling | 1187 | 525 | 974 |

| Malmö-Copenhagen | Scaniah | 283 | 12 237i | 14 806i |

| Stockholm | Stockholmj | 1975 | 14 112 | 17 008 |

| Oslo | Oslok | 573 | 8412 | 10 373 |

| Helsinki | Uusimaa and Itä-Uusimaal | 1484 | 399 | 498 |

| Brussels | Brusselsm | 1081 | 2573 | 3061 |

| Lille-Kortrijk | West Flandersn,o | 1130 | 630 | 654 |

| Antwerp | Antwerpn | 1683 | 1054 | 1127 |

| Madrid | Madridp | 6252 | 946 | 1052 |

| Barcelona | Barcelonap | 5330 | 755 | 783 |

| Valencia | Valenciap | 2268 | 420 | 451 |

| Seville | Sevillep | 1759 | 232 | 263 |

| Bilbao | Biscayp | 1330 | 349 | 362 |

| Rhine-Ruhr, Aachen, Liège, Maastricht, Bielefeld | North Rhein Westfaliaq | 18 075 | 836 | 932 |

| Berlin | Berlinq | 3400 | 173 | 217 |

| Hamburg | Hamburgq | 1735 | 73 | 126 |

| Frankfurt Rhine Main Area, Half of Rhine Neckar Area | Hesse, Rhineland-Palatinateq | 12 444 | 518 | 576 |

| Stuttgart, Half of Rhine Neckar Area | Baden-Württembergq | 10 717 | 478 | 575 |

| Munich, Nuremberg | Bavariaq | 12 444 | 638 | 628 |

| Halle-Leipzig, Chemnitz-wickau, Dresden | Saxony, Saxony Anhaltq | 6583 | 272 | 334 |

| Bremen, Hanover | Bremen, Lower Saxonyq | 8664 | 425 | 438 |

a: Current total population estimates

b: Preceded the creation of NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde from the split of NHS Argyll and Clyde in 2006

c: Health board in the Scottish Health Survey 2003 (response 67%)

d: Strategic health authority in the Health Survey for England 2002 (75%), 2003 (73%) and 2004 (72)

e: Health and social services board in the Northern Ireland Health and Wellbeing Survey 2001 (68%) and 2005 (66%)

f: Unitary authority in the Welsh Health Survey 2003 (74%) and 2004 (74%)

g: County (Republic of Ireland) in the Survey on Lifestyle and Nutrition 2002 (53%)

h: County (Sweden) in the Health Survey for Scania 2004 (58%)

i: Sex unknown thus imputed for 920 Scania individuals

j: County (Sweden) in the Stockholm Public Health Survey 2002 (63%)

k: County (Norway) in The Oslo Health Study 2001 (46%)

l: Region in Health Behaviour among the Finnish Adult Population Survey 2003 (67%)

m: Brussels-Capital Region in the Health Interview Survey Belgium 2004 (61%)

n: Province in the Health Interview Survey Belgium 2004 (61%)

o: The Lille-Kortrijk region spans France as well as Belgium; as the area covering Kortrijk, West Flanders is used as a proxy for the entire region

p: Province in the Spanish Health National Survey 2001 (85%)

q: State in the German Telephone Health Survey 2003 (60%)

Classification of variables

Measures of highest educational qualification attained were categorized into (i) none, (ii) below degree level, (iii) degree level or above (reference category) and (iv) unclassifiable (Supplementary table 1), broadly corresponding with level 1 (elementary education), levels 2 and 3 (lower and upper secondary education) and levels 4–6 (post-secondary education) of the International Standard Classification of Education.17 Occupation-based social class was categorised into (i) semi-skilled manual/unskilled manual, (ii) skilled non-manual/skilled manual, (iii) equivalent to professional/managerial (reference category) and (iv) unclassifiable (including missing/insufficient information e.g., retired) (Supplementary table 1).

The following health outcomes were examined: self-rated health; long standing illness; acute sickness; psychological distress and obesity. Participants were asked to rate their own health in general, whether they had any longstanding illness, disability or infirmity and whether they had experienced any illness or injury during the 2 weeks prior to the interview (Supplementary table 2). Psychological distress was measured by the widely used General Health Questionnaire 12 (GHQ-12) protocol on recent concentration, sleeping patterns, self-esteem and depression.23 Although the GHQ-12 does not enable clinical diagnosis-specific psychiatric diseases, it is used to investigate impaired psychological health in the population,24 with scores of three or more indicating possible ‘caseness’ referred to herein as psychological distress.

Body mass index (BMI) was derived from height and weight (directly measured in Scotland, England, Northern Ireland and Norway, and self reported elsewhere). Individuals with directly quantified measurements indicating BMI of 30 kg/m2 or more were considered obese, while participants in surveys collecting self-reported measurements were classified according to the more conservative cut-off of 29.2 kg/m2, shown to offer the optimal threshold.25

Statistical methods

Logistic regression models were fitted within a multilevel framework26 with individuals nested within geographical areas. Area residual plots show a measure (on the log odds ratio scale) of the difference between each area and the overall European average (equivalent to a residual value of 0) and they enable comparisons across the areas. First, the prevalence of each health measure was modelled adjusting for age to account for differential age ranges in the surveys (table 2). Then analysis incorporated additional adjustment by social class and education to assess the effect of socio-economic factors on the relationship between area and health measures. Comparing residual values and confidence intervals before and after adjustment allows assessment of the degree of socio-economic confounding. To avoid potential bias, multiple imputation was used to deal with missing data items using Rubin’s method.27 Models were stratified by sex since both biological factors and social constructs conditioned by gender may modify expression of health outcomes. Analyses were performed in MLwiN 2.02 and SAS 9.1.

Table 2.

Distribution of socio-demographics European regional area (%)

| Area | Age mean (range) | Education |

Social class |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Degree or above | Below degree | No qualifications | Unknown | Professional/ Managerial/ technical | Skilled | Semi- skilled/ unskilled | Unknown | ||

| Greater Glasgow | 48.4 (16–94) | 21 | 36 | 43 | 1 | 30 | 42 | 27 | 6 |

| Lothian | 48.4 (16–90) | 30 | 40 | 30 | 1 | 40 | 41 | 19 | 4 |

| London | 42.0 (16–98) | 24 | 54 | 22 | 1 | 42 | 42 | 16 | 2 |

| Greater Manchester, Cheshire and Merseyside | 45.4 (16–97) | 13 | 62 | 25 | 0 | 34 | 46 | 20 | 1 |

| Birmingham and the Black Country, West Midlands South | 45.8 (1–94) | 14 | 58 | 28 | 0 | 35 | 42 | 23 | 1 |

| West Yorkshire | 43.4 (16–99) | 13 | 63 | 24 | 1 | 35 | 45 | 20 | 2 |

| Northumberland, Tyne and Wear | 46.5 (16–92) | 12 | 58 | 30 | 0 | 32 | 42 | 26 | 1 |

| Trent | 45.3 (16–95) | 11 | 62 | 27 | 0 | 29 | 48 | 23 | 0 |

| South Yorkshire | 47.5 (16–96) | 16 | 63 | 20 | 0 | 43 | 39 | 18 | 2 |

| Hampshire and Isle of Wight | 46.6 (16–93) | 11 | 62 | 26 | 0 | 34 | 44 | 22 | 1 |

| Eastern Northern Irelanda | 46.9 (16–95) | 16 | 67 | 17 | 24 | 44 | 23 | 33 | 40 |

| Cardiff | 46.6 (16–75+) | 25 | 50 | 25 | 7 | 44 | 18 | 38 | 9 |

| Dublin | 46.9 (16–97) | 29 | 37 | 34 | 9 | 55 | 33 | 13 | 0 |

| Scania | 48.6 (18–81) | 36 | 24 | 40 | 10 | 40 | 38 | 23 | 41 |

| Stockholm | 47.9 (18–84) | 36 | 30 | 34 | 0 | 48 | 30 | 22 | 7 |

| Oslo | 51.1 (31–77) | 41 | 21 | 38 | 5 | 30 | 62 | 8 | 31 |

| Southern Finlandb | 41.2 (16–64) | 46 | 41 | 13 | 2 | – | – | – | – |

| Brussels | 49.4 (16–102) | 11 | 66 | 23 | 16 | 34 | 44 | 22 | 21 |

| West Flanders | 49.5 (16–98) | 23 | 57 | 20 | 9 | 47 | 38 | 16 | 11 |

| Antwerp | 49.9 (16–103) | 9 | 69 | 23 | 13 | 30 | 50 | 19 | 14 |

| Madridc | 45.2 (16–90+) | 12 | 65 | 23 | 1 | 34 | 45 | 22 | 21 |

| Barcelonac | 45.0 (16–90+) | 20 | 51 | 29 | 0 | 21 | 50 | 29 | 14 |

| Valenciac | 44.9 (16–90+) | 14 | 56 | 30 | 0 | 16 | 52 | 31 | 17 |

| Sevillec | 43.3 (16–90+) | 14 | 48 | 38 | 0 | 18 | 46 | 36 | 25 |

| Biscayc | 46.0 (16–90+) | 10 | 48 | 42 | 1 | 11 | 43 | 45 | 26 |

| North Rhein Westfaliad | 47.1 (18–95) | – | – | – | – | 23 | 48 | 29 | 14 |

| Berlind | 47.0 (18–91) | – | – | – | – | 27 | 63 | 9 | 15 |

| Hamburgd | 45.8 (18–89) | – | – | – | – | 24 | 69 | 7 | 11 |

| Hesse, Rhineland-Palatinated | 45.8 (18–85) | – | – | – | – | 27 | 68 | 5 | 12 |

| Baden-Württembergd | 45.7 (18–89) | – | – | – | – | 26 | 66 | 8 | 13 |

| Bavariad | 45.6 (18–90) | – | – | – | – | 22 | 67 | 10 | 11 |

| Saxony, Saxony Anhaltd | 49.6 (18–89) | – | – | – | – | 24 | 68 | 8 | 11 |

| Bremen, Lower Saxonyd | 45.9 (18–91) | – | – | – | – | 15 | 76 | 8 | 13 |

| Total | 48.0 (16–90+) | 39 | 42 | 20 | 4 | 39 | 42 | 20 | 12 |

a: Social class proportions based on 2005 data only—data not available for 2001

b: Occupation data unavailable for Health Behaviour among the Finnish Adult Population Survey

c: Age given in ranges; mean age derived from age range

d: Education data unavailable for German Telephone Health Survey; Known percentage totals sum to (approximately) 100% for ease of comparison among areas

Results

Data were available on 56 853 men, 69 080 women and 920 individuals for whom sex had not been recorded (table 1), average age 48.0 years (table 2). The mean number of records per area was 3844, ranging from 199 in Hamburg to 31 120 in Stockholm (table 1). Of the entire sample with available data, 20% had no formal qualifications, 42% were educated to below degree level and 39% had degree level or above qualifications (table 2). The overall breakdown by social class was 20% semi- or unskilled; 42% skilled occupations and 39% professional/managerial. However, distributions varied greatly across regions. The percentage with degree or above ranged from 9% in Antwerp to 46% in Southern Finland; professional/managerial from 11% in Biscay to 55% in Dublin.

Overall, 6% of men and 7% of women self-reported bad/very bad general health and this was highest among men and women in Greater Glasgow, and lowest among men in Antwerp and West Flanders and women in Antwerp. Longstanding illness prevalences were 32% for men and 34% for women overall and were most common in Hampshire and Isle of Wight and least common in West Flanders. Reported acute sickness incidence (15% for men and 20% for women overall) was highest in Trent and lowest in London. Psychological distress (13% for men and 18% for women overall) was most common among men in Greater Glasgow and women in Eastern Northern Ireland, and lowest in West Flanders. Comparing sexes, bad/very bad general health and long-standing illness were generally more prevalent in men for the UK areas but more prevalent for women in Belgian and Spanish areas, whereas acute sickness and high GHQ-12 were more prevalent for women in all areas. Generally, obesity (16% for men and 15% for women overall) was more common in women for UK and Belgian areas, but more common in men for other areas.

There was generally lower prevalence of unfavourable health in the professional/managerial classes and those with degree level or above education. Socio-economic gradients within areas were generally stronger for self-rated health, longstanding illness and obesity, and weaker for psychological distress and acute sickness. With the exception of obesity, socio-economic inequalities tended to be more pronounced for areas in the UK.

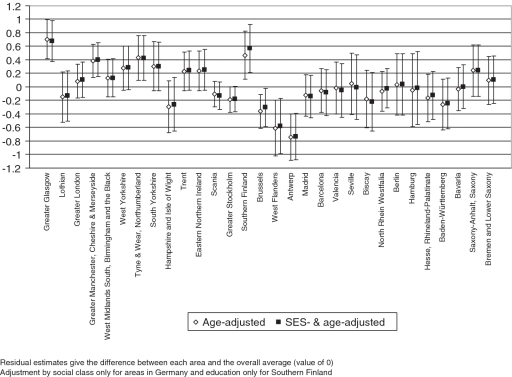

Figure 1 shows the differences between each area and the average for all metropolitan areas of self-reporting of bad/very bad general health for men adjusted for age, and age, education and social class. Age-adjusted self-reporting of bad/very bad general health among men was significantly higher than average in Greater Glasgow, Manchester/Cheshire and Merseyside and Southern Finland and significantly lower than average in the areas in Belgium (figure 1). Adjusting additionally for socio-economic measures did not alter results. Among women, levels were higher in Greater Glasgow, Eastern Northern Ireland, Madrid, Barcelona and Seville, and lower in West Flanders and Antwerp; results for Madrid, Barcelona and Seville were attenuated on socio-economic adjustment.

Figure 1.

Logistic regression residuals and 95% confidence intervals for self rating of bad/very bad general health for men

Longstanding illness rates were significantly higher than average in men in Trent and significantly lower in the areas in Sweden and Belgium; results were not attenuated by socio-economic adjustment. Levels for women were significantly higher than average for men in Greater Glasgow and the English regions—except London and Hampshire and Isle of Wight. Significantly lower than average levels were in seen in the selected areas in Sweden and Belgium. South Yorkshire had higher than average incidence of acute sickness—the only area with levels significantly different to the male average for all areas evaluated, but this was attenuated on adjustment for socio-economic factors. Women in Scania had significantly higher levels than average which were not attenuated by socio-economic adjustment; women in London had significantly lower levels than average.

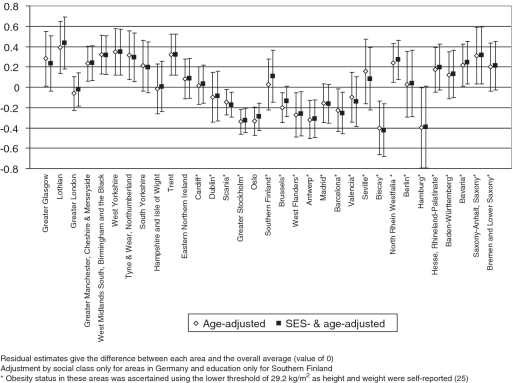

Obesity levels among men were significantly higher than average in Greater Glasgow, Lothian, Manchester/Cheshire and Merseyside, West Midlands South, Birmingham and the Black Country, West Yorkshire, Tyne and Wear, Northumberland, Trent, North Rhine-Westphalia, Bavaria and Saxony-Anhalt/Saxony and significantly lower than average in selected areas in Sweden and Belgium, Oslo, Barcelona, Biscay and Hamburg (figure 2). Results for Greater Glasgow, Brussels and Hamburg were attenuated on socio-economic adjustment. Among women, levels were significantly higher for Greater Glasgow, Manchester/Cheshire and Merseyside, West Midlands South, Birmingham and the Black Country, West Yorkshire, Trent, South Yorkshire and Saxony-Anhalt/Saxony and significantly lower than average in Dublin, in areas in Sweden and Belgium, Oslo, Southern Finland, Barcelona and Biscay. Analyses were performed with and without the cut-off of 29.2 kg/m2 for self-reported measurements and overall results were the same.

Figure 2.

Logistic regression residuals and 95% confidence intervals for obesity for men

Psychological distress among men was significantly higher than average in Greater Glasgow, Eastern Northern Ireland and Stockholm; West Flanders had significantly lower levels. Results were not attenuated by socio-economic adjustment; findings were similar for women with additionally lower than average levels in Scania and Antwerp.

Discussion

We found that indicators of impaired population health were generally higher than average in the metropolitan areas in the North and West of the UK and the central belt and south east of Germany, and lower in the areas in Sweden generally and those in north west Belgium included in the study, and this was generally the case in both men and women. Our findings also provide national as well as continental perspectives on the position of specific regions—e.g. Lothian and the London regions may be doing well relative to the other British areas, but badly compared with the selected continental regions overall. Others, e.g. Seville, appear unfavourable at a national level but are around the average when taken in the context of all the areas. These findings across metropolitan areas are not necessarily a direct reflection of rankings at the national level. Germany, for instance, generally has middle ranking amidst the countries for these health indicators, in contrast with that country’s metropolitan areas’ less favourable rankings.10 In most cases disparities could not be explained by variations in two key indicators of individual socio-economic position.

A study comparing mortality in sub-country urban areas in Europe with histories of post industrial decline, with some overlap in Scottish, German and Belgian areas included here, found equivalently high rates in the Glasgow area compared with other regions, despite its comparatively favourable socio-economic environment.28

Limitations

Variations in survey methodology may have impacted on findings such that within country differences are likely to be valid but between country differences may be due to measurement effects.

Survey conduct

There may be differences due to variation in language, though only items with similar phrasing were retained. Notwithstanding, there may have been mode effects, whereby differences in response arise from data collection method (e.g. telephone survey or face-to-face interview).29 There remain issues around the validity of comparing self-reported measures of health between different countries with distinct cultures and attitudes: self reports of health are influenced not only by physical condition, but also by awareness, expectation and comparison which may be culturally determined.30 Responses to self-assessed items were based on informants’ recall and judgements and as such were subject to distortion due to variations in individual perceptions, even within areas. There are a range of choices of cut-off for self-rated health—we chose the one which reflects less than fair or average health. It is possible bias in self-reporting of anthropometry measurements, especially weight, may account for findings of lower obesity in some areas,31 but we hope the correction factor has gone some way towards addressing this.25

Socio-economic measures

In using the chosen socio-economic classifications, we have attempted to create homogeneous groups; specifically, the education categorization follows closely the degree/other/none scheme, previously found to be consistent across countries.32 However, it is clearly difficult to equivalize categories (e.g. we found large differences between Biscay and Dublin), therefore, arising residual confounding may reduce the validity of our findings. It is possible other material measures—such as income and economic security—could further explain the differences between regions but, since they are strongly correlated with occupation and education, we feel it unlikely their addition would yield very different results. Variations in factors operating at the regional or national levels (e.g. welfare expenditure, regeneration) may be additional sources of between-region differences but such assessment is beyond the scope of this study.

Survey response

Differences in response levels between surveys may have introduced differential selection bias, most likely resulting in underestimation of poor health in those with low response. Of the areas found to have higher levels of poor health, those in the UK have some of the highest survey response levels. If any bias was indeed active, it may result in overestimation of the differences between those and the average levels; with lower response rates, the converse would be true of the German areas. However, validation can be seen from the Welsh Health Survey, in which there was no difference in the proportion of adults reporting ‘not good’ general health between respondents and refusers.33 Furthermore, response levels quoted were those for the entire surveys (in most cases it was not possible to obtain area-specific values) but there were geographical differences within at least some surveys,34 and many of the areas potentially have lower values. Weighting schemes have been used in some surveys to address under-representation in some age, sex and socio-economic groups. However, since weighting strategies were heterogeneous it was not possible to weight in composite, and differences in underlying composition of the samples may have impacted on the results, although stratification by sex and adjustment by age and socio-economic variables should have resolved this to some extent.

Sampling

Surveys did not necessarily sample from equivalent populations, with most including only individuals living in private households—excluding those living in institutions, who were likely to be older and, on average, in poorer health35—while others (e.g. in Belgium) were more inclusive. For a few areas, the sample sizes were relatively small and interpretation requires caution. There can be temporal trends in health indicators—most importantly increasing obesity36—and surveys were not all conducted in the same year, although they did take place within a relatively short window of time. Also, differences in urban/rural characteristics of areas may be behind the observed differences but it is unlikely that they would explain all of the variation.

Conclusions

This collaboration represents the first examination of metropolitan area variations in health measures and, despite the outlined caveats, offers insight for the future monitoring of population health in Europe. We have identified limitations of the available information and the complexity of harmonizing data from different national surveys. Ideally, comparisons would be made using a standardized protocol for sampling, recruitment, data collection (including wording of the questionnaire and measurement protocols) and analysis. At present, this does not exist for nationally representative samples to allow comparison of areas within and between countries. Some multi-centre studies such as MONICA,37 and EPIC38 have used standardized methods but cover only small areas. Although it is mandatory for each EU member state to conduct the European Health Interview Survey (EHIS) by 2013,39 there are difficulties with funding and planning this, particularly for countries with existing but different survey series. A European Health Examination Survey is currently being piloted, based on recommendations from the FEHES study20 attempting to avoid the pitfalls we have identified in this study. This will enable superior comparisons to be made across Europe for public health monitoring both at national level and, where participant numbers are large enough, by population sub-groups such as demographic factors, socio-economic status, as well as region. Such surveys will allow proper monitoring of health inequalities with reliable comparability between regions and countries and, thereby, support evidence-based public health policies.

Supplementary data

Supplementary data are available at EURPUB online.

Funding

Glasgow Centre for Population Health; Chief Scientist Office of the Health Directorate of the Scottish Government WBS U.1300.00.001.00013.01.

Conflicts of interest: None declared.

Key points.

What is already known on this subject?

Population health varies across countries in Europe.

The increasing concentration of populations into large metropolitan centres in recent decades has not been matched by international health assessments which hitherto largely focused on the national level.

There is a need to compare health measures across Europe metropolitan areas and to determine the extent to which differences are due to socio-economic factors.

What does this study add?

Findings suggest indicators of poor health are generally higher than average in the metropolitan areas in the north and west of the UK and the central belt and south east of Germany and lower in the areas in Sweden generally and north west Belgium.

Variations between the socio-economic composition of the local area populations do not explain European metropolitan health differences.

Further research based on internationally standardized survey data is required to explore the underlying causes of Europe metropolitan health differentials and inform health policy.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Thanks go to Prof Carol Tannahill, David Walsh, Rosalia Munoz-Arroyo and Cath Roberts for useful discussion. Additional thanks to ScotCen, UK and the UK Data Archive for data provision.

References

- 1.Leon DA, Morton S, Cannegieter S, McKee M. Understanding the Health of Scotland's Population in an International Context. A Review of Current Approaches, Knowledge and Recommendations for New Research Directions. London: London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine and Public Health Institute of Scotland; 2003. February 2003 (2nd revision) [Google Scholar]

- 2.White paper. Together for Health – A Strategic Approach for the EU, 2008-2013. Brussels: Commission of the European Communities; 23 October 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Project Technical Working Group on City Health Profiles. City Health Profiles: How to report on Health in your city. Copenhagen, Denmark: WHO Regional Office for Europe; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dalstra JA, Kunst AE, Borrell C, et al. Socioeconomic differences in the prevalence of common chronic diseases: an overview of eight European countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:316–26. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kunst AE, Bos V, Lahelma E, et al. Trends in socioeconomic inequalities in self-assessed health in 10 European countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:295–305. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Merlo J, Asplund K, Lynch J, et al. Population effects on individual systolic blood pressure: a multilevel analysis of the World Health Organization MONICA project. Am J Epidemiol. 2004;159:1168–79. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sacker A, Wiggins RD, Bartley M, McDonough P. Self-rated health trajectories in the United States and the United Kingdom: a comparative study. Am J Public Health. 2007;97:812–8. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2006.092320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Eurostat. Theme Population and social conditions. Health in Europe. Data 1998-2003. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 9.WHO Global InfoBase team. The SuRF Report 2: Surveillance of Chronic Disease Risk Factors: Country-level Data and Comparable Estimates. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bayingana K, Tafforeau J. Comparison of European health surveys results for the period 2000-2002. Brussels: Epidemiology Unit, Scientific Institute of Public Health; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olsen KM, Dahl SA. Health differences between European countries. Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1665–78. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.11.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Health Indicators in the European Regions. Final report ISARE Project n° 2001/IND/2101. Paris: Fédération nationale des observatoires régionaux de la santé; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tunstall-Pedoe H, Kuulasmaa K, Amouyel P, et al. Myocardial infarction and coronary deaths in the World Health Organization MONICA Project. Registration procedures, event rates, and case-fatality rates in 38 populations from 21 countries in four continents. Circulation. 1994;90:583–612. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.90.1.583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eurostat. The European Community Household Panel. Available at: http://forum.europa.eu.int/irc/dsis/echpanel/info/data/information.html (25 September 2009, date last accessed)

- 15.Ustun TB, Chatterji S, Villanueva M, et al. Global Programme on Evidence for Health Policy. Discussion Paper No. 37. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2001. WHO Multi-country survey study on health and responsiveness 2000–2001. [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. World Health Survey. World Health Organization; Available at: http://www.who.int/healthinfo/survey/en/index.html (25 September2009, date last accessed)

- 17.International Standard classification of Education 1997, re-edition May 2006. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cavelaars AE, Kunst AE, Geurts JJ, et al. Differences in self reported morbidity by educational level: a comparison of 11 western European countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1998;52:219–27. doi: 10.1136/jech.52.4.219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cavelaars AE, Kunst AE, Geurts JJ, et al. Morbidity differences by occupational class among men in seven European countries: an application of the Erikson-Goldthorpe social class scheme. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:222–30. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.2.222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tolonen H, Koponen P, Aromaa A, et al. Helsinki: Publications of the National Public Health Institute; Recommendations for the Health Examination Surveys in Europe. B21/2008. 2008 available at: http://www.ktl.fi/attachments/suomi/julkaisut/julkaisusarja_b/2008/2008b21.pdf (8 November 2010, date last accessed) [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sogaard AJ, Selmer R, Bjertness E, Thelle D. The Oslo Health Study: the impact of self-selection in a large, population-based survey. Int J Equity Health. 2004;3:3. doi: 10.1186/1475-9276-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.European metropolitan areas. Journal [serial on the Internet] Available at: http://www.world-gazetteer.com/ (8 November 2010, date last accessed)

- 23.Goldberg D, Williams PA. Users Guide to the General Health Questionnaire. Windsor: NFER-Nelson; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parslow RA, Jorm AF. Who uses mental health services in Australia? An analysis of data from the National Survey of Mental Health and Wellbeing. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34:997–1008. doi: 10.1080/000486700276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dauphinot V, Wolff H, Naudin F, et al. New obesity body mass index threshold for self-reported data. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63:128–32. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.077800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Snijders TAB, Bosker RJ. Multilevel Analysis: An Introduction to Basic and Advanced Multilevel Modeling. London: Sage Publishers; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rubin DB. Multiple Imputation for Nonresponse in Surveys. New York: John Wiley & Sons, Inc; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walsh D, Taulbut M, Hanlon P. The aftershock of deindustrialization–trends in mortality in Scotland and other parts of post-industrial Europe. Eur J Public Health. 2010;20:58–64. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckp063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tipping S, Hope S, Pickering K, et al. The effect of mode and context on survey results: analysis of data from the Health Survey for England 2006 and the Boost survey for London. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2010;10:84. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-10-84. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mitchell R. Commentary: the decline of death–how do we measure and interpret changes in self-reported health across cultures and time? Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:306–8. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nyholm M, Gullberg B, Merlo J, et al. The validity of obesity based on self-reported weight and height: Implications for population studies. Obesity. 2007;15:197–208. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Review of the International Standard Classification of Education (ISCED) Paris: UNESCO Institute for Statistics; 9–10 July 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 33.McGee A, Jotangia D, Prescott A, et al. Welsh Health Survey - Year One. Technical Report. Cardiff: Prepared for the Welsh Assembly Government; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sproston K, Primatesta P, editors. Health Survey for England. 2003, Vol. 3, Methodology and documentation. London: The Stationery Office, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Craig R, Deverill C, Pickering K, Prescott A. Technical Report, Vol. 4. Chapter 1: Methodology and Response. In: Bromley S, Sproston K, Shelton N, editors. The Scottish Health Survey 2003. Edinburgh: The Scottish Executive Department of Health; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 36.James WP. The epidemiology of obesity: the size of the problem. J Intern Med. 2008;263:336–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.2008.01922.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators. The World Health Organization MONICA Project (monitoring trends and determinants in cardiovascular disease): a major international collaboration. WHO MONICA Project Principal Investigators. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41:105–14. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90084-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Margetts BM, Pietinen P. European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition: validity studies on dietary assessment methods. Int J Epidemiol. 1997;26(Suppl. 1):S1–5. doi: 10.1093/ije/26.suppl_1.s1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Working Group “Public Health Statistics”. Health interview survey data, statistics on disability (HIS). Luxembourg: Eurostat European Commission Directorate F: Social Statistics and Information Society Unit F-5: Health and food safety statistics 26–27 October 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.