Abstract

KCC2 comprises the major Cl− extruding mechanism in most adult neurons. Hyperpolarizing GABAergic transmission depends on KCC2 function. We recently demonstrated that glutamate reduces KCC2 function by a phosphorylation-dependent mechanism that leads to excitatory GABA responses. Here we investigated the methods by which to estimate changes in EGABA, as well as the processes that lead to depolarizing GABA responses and their effects on neuronal excitability. We demonstrated that current-clamp recordings of membrane potential responses to GABA can determine upper and lower limits of EGABA. We also further characterized depolarizing GABA responses, which both excited and inhibited neurons. Our analyses revealed that persistently active GABAA receptors contributed to loading Cl− during the glutamate exposure, indicating that tonic inhibition can facilitate the development of depolarizing GABA responses and increase excitability after pathophysiological insults. Finally, we demonstrated that hyperpolarizing GABA responses could temporarily switch to depolarizing responses when they coincided with an after hyperpolarization.

Key words: KCC2, GABA, EGABA, glutamate, depolarizing, tonic inhibition, phasic inhibition, phosphorylation, afterhyperpolarization

Introduction

GABAA and glycine cysteine-loop receptors are the two main Cl− permeable ion channels in neurons. These receptors perform their canonical inhibitory roles by allowing Cl− to passively diffuse into the neuron and hyperpolarize the membrane potential. Cl− entry and membrane hyperpolarization are determined by ion pumps, which translocate Cl− out of the neuron. The K+/Cl− cotransporter type 2 (KCC2) constitutes the major Cl− extruding mechanism in neurons, pushing the reversal potential of GABA-activated currents (EGABA) below the resting membrane potential (RMP).1 Without KCC2, EGABA would be greater than or equal to the RMP, resulting in shunting inhibitory or depolarizing responses mediated by GABAA receptors.

During development GABA is the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain because EGABA values are higher than the RMP.2 The Na+/K+/Cl− cotransporter type 1 (NKCC1) persistently loads neurons with Cl− and is expressed throughout development and into adulthood.3,4 However, KCC2 expression is dramatically increased over the first two postnatal weeks in rodent brain. Despite any remaining NKCC1 activity, KCC2 becomes the dominant influence on Cl− homeostasis in nearly all subcellular domains of principle neurons.

Phosphorylation, membrane trafficking, and protein degradation tightly control KCC2 function. We recently revealed that glutamate regulates KCC2 function by a phosphorylation-dependent mechanism.5 The phosphorylation state of residue Ser 940 is controlled by the opposing influences of protein kinase C and protein phosphatase 1. Phosphorylation of Ser 940 increases Cl− extrusion and membrane stability, whereas glutamate-induced dephosphorylation favors internalization and degradation of KCC2. Glutamate exposure causes a dramatic sustained shift of EGABA to more positive potentials within minutes. In this paper we further characterized the Cl− loading phase, the multiple roles of depolarizing GABA and the dependence of GABA responses on the membrane potential.

Results

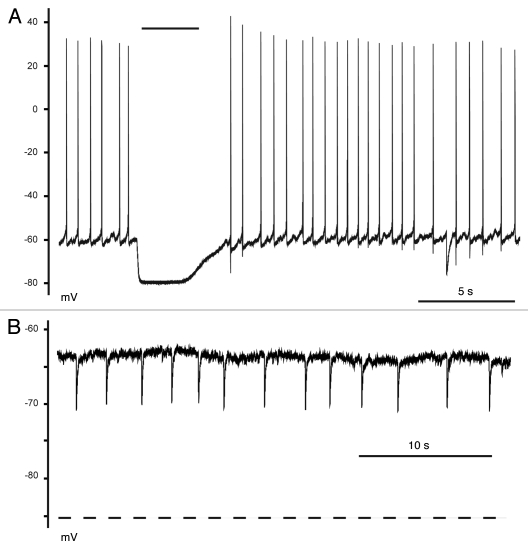

We began our experiments on cultured hippocampal neurons by recording the GABA responses in the absence of any antagonists (Fig. 1A). These data demonstrated that exogenous GABA applications were hyperpolarizing and inhibitory. Voltage-clamp protocols are the standardized methods for determining EGABA. However, data obtained in current-clamp can also provide estimates and/or limits of EGABA, as it is physically impossible for the peak of a voltage response to GABA to exceed EGABA. Analyzing our previously published data in this manner, we found that the peak of GABA-activated hyperpolarizing potentials averaged across all neurons tested was −73 ± 2 mV (n = 22), which underestimated the averaged EGABA value determined by voltage-clamp by ∼6 mV.5 After exposure to glutamate, the GABA-activated potentials peaked at −59 ± 2 mV (n = 22), which includes data from neurons that exhibited purely shunting or hyperpolarizing responses, and also underestimated the averaged EGABA value by ∼7 mV.5 The amplitudes of these GABA responses shifted from −7.9 ± 1.1 mV under control conditions to 4.1 ± 1.3 mV after glutamate exposure. Given that the membrane potential did not significantly change, we estimated from these data an ∼13 mV shift in EGABA that resulted in a flip of the polarity of the GABA responses. While this shift was far less than the ∼27 mV shift determined by voltage-clamp protocols, we could still conclude from our current-clamp experiments that EGABA significantly shifted to more positive potentials and that these neurons could not establish hyperpolarizing GABA responses due to the glutamate-induced loss of KCC2 function.5

Figure 1.

The canonical role of GABA. (A) GABA (10 µM-black bar) shunted membrane conductances causing a hyperpolarization of the membrane potential and inhibited spontaneous action potentials. Recordings were obtained in current-clamp mode and in the absence of any antagonists. (B) Spontaneous IPSP hyperpolarized the membrane potential. The EGABA value obtained by voltage-clamp protocols for this neuron is indicated by the dotted line (−85.4 mV). These data were obtained in the presence of DNQX and AP5.

We then analyzed spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (sIPSP) in a similar manner. The peak voltage of sIPSP measured on three neurons was −67 ± 3 mV, with amplitudes of −6.7 ± 0.6 mV (Fig. 1B). The averaged EGABA value obtained from these cells using voltage-clamp protocols was −83 ± 2 mV. While the sIPSP also underestimated EGABA, the peak potentials and polarity of the responses can be used to determine an upper limit of EGABA, in this case ∼−67 mV, and to indicate that the neuron expressed a mechanism to sustain hyperpolarizing responses, e.g., functional KCC2. Using current-clamp mode to determine lower or upper limits of EGABA both simplifies the measurement of EGABA and avoids Cl− loading and unloading errors produced by the extreme driving forces in voltage-clamp protocols.

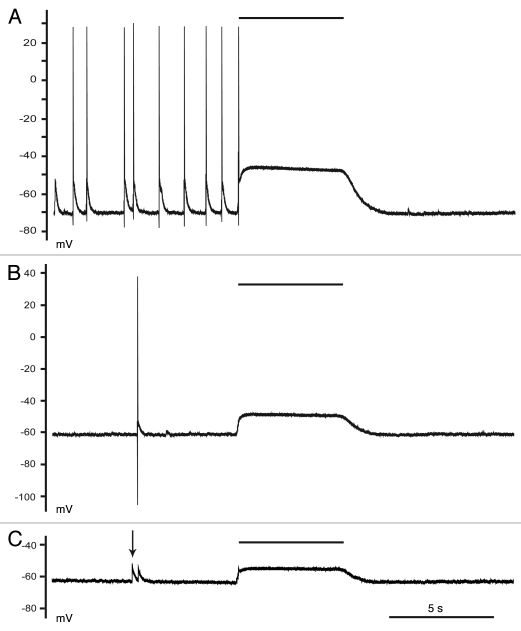

Our previous experiments demonstrated that a 2 min glutamate application results in depolarizing GABA responses.5 Further analysis indicated that these responses were not always excitatory. Two minutes after the glutamate pulse, both synaptic and exogenous GABA (10 µM) elicited action potentials (Fig. 2A). However, because the GABA conductance and EGABA values were so high, the exogenous GABA application elicited one action potential before shunting all additional membrane conductances. Four minutes later however, only phasic GABA elicited action potentials, whereas the exogenous GABA only depolarized the neuron (Fig. 2B). The difference between these responses was likely due to the higher concentration of GABA in the synaptic cleft.6 Eight minutes after the glutamate exposure neither the synaptic nor the exogenous GABA elicited action potentials (Fig. 2C). These data indicated that the neuron could not sustain the high Cl− load incurred during the glutamate pulse, and so the EGABA values eventually reached an equilibrium potential closer to but more depolarized than the RMP.

Figure 2.

Depolarizing GABA was more versatile than hyperpolarizing GABA. Recordings were obtained from a neuron that was exposed to glutamate (20 µM) for 2 min. (A) Two minutes after the end of the glutamate pulse spontaneous GABAergic excitatory postsynaptic potentials elicited multiple action potentials. A pulse of exogenous GABA (10 µM) elicited a single action potential before shunting further activity. (B) Four minutes after the end of the glutamate pulse only the phasic GABA responses triggered action potentials. (C) Eight minutes after the end of the glutamate pulse neither the phasic responses (arrow) nor the exogenous GABA triggered action potentials. All recordings were obtained in the presence of DNQX and AP5. Black bars indicate the duration of the GABA applications. Scale bar in (C) is for all traces.

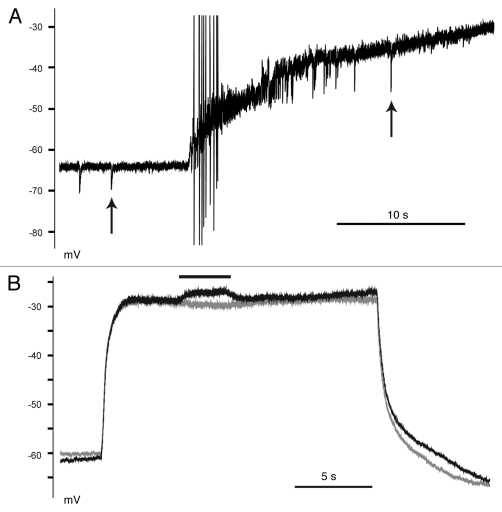

Our previous work demonstrated that GABAA receptors mediated a significant portion of Cl− loading during the glutamate pulse.5 Close inspection of the rising phase of the glutamate pulse revealed a short burst of sIPSP (Fig. 3A). The glutamate-induced depolarization should increase the driving force on GABA, however, the averaged amplitudes of the sIPSP measured during the glutamate pulse (−6.1 ± 0.5 mV) were not significantly greater than controls (−5.4 ± 0.2 mV, p = 0.1751, paired t-test). Furthermore, this GABAergic activity only lasted several seconds prior to the depolarizing block phase, making statistical analyses difficult due to the small sample size. This brief period of activity suggested that the phasic inhibitory activity was insufficient to cause the shift in EGABA. In contrast, tonic inhibition conducts >3-fold more Cl− ions than synaptic currents in cerebellar granule cells.7 We therefore performed a separate set of experiments in which we stepped neurons from a solution containing glutamate into a solution containing glutamate and bicuculline (Fig. 3B). The average bicuculline voltage response was 3.4 ± 0.9 mV (n = 5), indicating the presence of a tonic bicuculline-sensitive hyperpolarizing current throughout the glutamate pulse. We concluded the tonic GABAergic hyperpolarizing currents mediated a large portion of the Cl− loading during the glutamate exposure.

Figure 3.

Tonic currents contributed to Cl− loading during the exposure to glutamate. (A) Spontaneous IPSP (arrows) were observed prior to and during the depolarizing glutamate pulse. Activity quickly ceased after several seconds due to depolarizing block. Glutamate was applied without any antagonists. (B) Bicuculline (solid line) caused a depolarizing potential during the glutamate pulse. Two consecutive traces are superimposed to illustrate the effect of bicuculline: the trace in black contains the glutamate and bicuculline/glutamate pulse, the trace in gray was glutamate alone. Recordings were obtained in the presence of TTX, DNQX and AP5, while glutamate and bicuculline were applied alone.

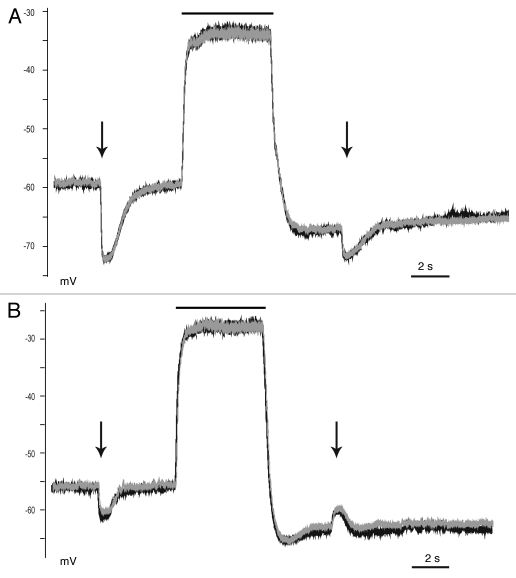

Our experiments also revealed that glutamate caused a pronounced afterhyperpolarization (AHP). We therefore performed a set of experiments testing the effects of GABA prior to a 5 s glutamate pulse and then during the glutamate-induced AHP. GABA applied prior to glutamate hyperpolarized the membrane potential, indicating the presence of functional KCC2 (Fig. 4). However, during the AHP, the GABA test pulse produced either a second hyperpolarizing response (Fig. 4A) or a depolarizing response (Fig. 4B). This procedure was repeated several times to demonstrate that the depolarizing responses were caused by the strong AHP, not by shifts in EGABA. In the first group of neurons, EGABA was sufficiently hyperpolarized such that the AHP did not exceed EGABA. However, in some neurons (three of 10 tested), EGABA was close enough to the RMP that the AHP became more negative than EGABA, and hence created a condition that gave rise to a depolarizing GABA response despite KCC2 activity. These data directly demonstrated that GABA responses were not only dependent on the EGABA value, but also on membrane potential fluctuations.

Figure 4.

The polarity of the GABA responses depended on the membrane potential. Neurons were exposed to a 500 ms GABA pulse (10 µM, arrows) before and after a 5 s glutamate pulse (20 µM, black bar). (A) Several neurons exhibited hyperpolarizing GABA responses both before and during the glutamate-induced AHP. (B) Several neurons exhibited a weaker hyperpolarizing GABA response, and a depolarizing GABA response during the glutamate-induced AHP. Consecutive traces (black and gray, 1/60 s) are overlaid to demonstrate that transient shifts in EGABA did not occur. Recordings were obtained in the presence of TTX, DNQX and AP5.

Discussion

Our latest findings revealed that while the canonical role of GABA is to hyperpolarize the membrane, their activity can backfire during neurological insults. Furthermore, whether it is caused by insult or is naturally occurring, depolarizing GABA has a far more versatile effect on neuronal excitability than does hyperpolarizing GABA. We also found that fluctuations in the membrane potential can determine responses to GABA.

KCC2 activity is very susceptible to neurological insult, as others and we have demonstrated.4,5,8 The loss of KCC2 expression results in overwhelming Cl− loading by NKCC1 and GABAA receptors, which can result in excitotoxic damage. Indeed, negative allosteric modulators of specific GABAA receptors that mediate tonic inhibition prevented Cl− loading after ischemia, thereby reducing the infarct size in mice.9 Our data demonstrating a tonic GABAergic current during the glutamate pulse supports the hypothesis that tonic inhibition can exacerbate neuronal damage when KCC2 function is lost.

We observed depolarizing GABA responses with various effects on membrane excitability after the loss of KCC2. Depolarizing GABA induced depolarizing block, indicating that a surge in tonic depolarizing conductance could be sufficient to prevent the de-inactivation of NaV channels and prevent excitation despite suprathreshold GABA responses. Such surges in ambient GABA concentrations occur during seizures in conscious human brain.10 After EGABA decreased, only saturating GABA concentrations produced conductances high enough to reach threshold and activate action potentials. Indeed, CA1 stratum radiatum interneurons exhibit variable membrane responses that depend on the conductance of depolarizing GABA responses.11

The effect of GABA on membrane potential is determined by the difference between EGABA and the membrane potential. Although much evidence indicates that GABA responses depend on EGABA, little attention has focused on how membrane fluctuations could alter GABA responses. Here we demonstrated that GABA responses flipped polarity under certain conditions: an EGABA value close to the RMP and a neuron, which exhibits a pronounced AHP that exceeds EGABA. But the role of a depolarizing GABA response during an AHP is unclear. It is possible that such an alternating phasic GABAergic shunt is entirely experimental. At the very least, these data were simply demonstrable proofs of how GABA conductances can shunt any voltage deviations from EGABA, whether these deviations are hyperpolarizing or depolarizing. If real, however, the depolarizing postsynaptic potentials during the AHP could shorten the length of interspike intervals, possibly improving network synchronization.12,13 An intriguing possibility is that the efficacy and polarity of GABA responses fluctuate at the axon initial segment of pyramidal neurons, where there is an ongoing debate over EGABA values and the efficacy of GABAergic transmission.14–17 Furthermore, a temporal- and voltage-dependent dual GABAergic shunt could also contribute to phase-locking subtypes of interneurons and hippocampal pyramidal cells.14,18

While our work sheds more light on the mechanism of the shift in EGABA values during exposure to glutamate, our work provides evidence challenging the static role of GABA. It is increasingly evident that Cl− homeostasis in neurons is highly dynamic. Further examination of EGABA and endogenous GABAergic signaling must take into account several factors including fluctuations in membrane potential as well as the surface activity and phosphorylation state of KCC2, not just its expression.19–21 Our work highlights the potential benefits and hazards of therapeutic and laboratory agents that target GABAA receptors.

Materials and Methods

The experiments in this study were performed as described previously in reference 5. Briefly, we used the gramicidin (50 µg/mL) perforated patch technique in every recording. All experiments were performed at 34°C and all compounds were applied locally by gravity-feed. The recording electrodes contained (in mM) 140 KCl and 10 HEPES, pH 7.4 KOH. Bath solutions contained (in mM) 140 NaCl, 4.7 KCl, 2.5 CaCl2, 1.2 MgCl2, 10 HEPES, 11 glucose, pH 7.4 NaOH. We used TTX (500 nM), DNQX (20 µM) and AP5 (50 µM) to block NaV channels, AMPA receptors and NMDA receptors, respectively; glutamate was applied without these antagonists. All compounds were purchased from Sigma Aldrich. All data were obtained using an Axopatch 200B amplifier and pClamp 8 software (Axon Instruments). Data were recorded onto a PC for offline analysis using Clampfit. All records were filtered at 2 kHz and digitized at 10 kHz. We used the Mini Analysis program (Synaptosoft) to analyze spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic potentials. For these experiments, we analyzed 50 consecutive phasic responses for each neuron. We used GraphPad Prism 4 software for statistical analyses. We used paired and unpaired t-tests and one-way ANOVA with a post hoc Dunnett's test where indicated. We constructed I–V plots and fit the data points by linear regression analysis using GraphPad Prism software to determine EGABA values.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Jamie Maguire for critical comments on the manuscript and Dr. Hong Tang and Liliya Silayeva for providing technical assistance. The work was supported in part by NIH/NINDS grants NS036296, NS047478, NS048045 and NS054900. The article must be marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC. Section 1734 solely to indicate this fact.

Abbreviations

- KCC2

K+/Cl− cotransporter type 2

- NKCC1

Na+/K+/Cl− cotransporter type 1

- GABA

γ-aminobutyric acid

- EGABA

reversal potential of GABA-activated currents

- GABAA

GABA type A receptors

- sIPSP

spontaneous inhibitory postsynaptic potentials

- RMP

resting membrane potential

- AHP

afterhyperpolarization

References

- 1.Payne JA, Stevenson TJ, Donaldson LF. Molecular characterization of a putative K-Cl cotransporter in rat brain. A neuronal-specific isoform. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:16245–16252. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.27.16245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ben-Ari Y. Excitatory actions of GABA during development: the nature of the nurture. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2002;3:728–739. doi: 10.1038/nrn920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Plotkin MD, Snyder EY, Hebert SC, Delpire E. Expression of the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter is developmentally regulated in postnatal rat brains: a possible mechanism underlying GABA's excitatory role in immature brain. J Neurobiol. 1997;33:781–795. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4695(19971120)33:6<781::aid-neu6>3.0.co;2-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blaesse P, Airaksinen MS, Rivera C, Kaila K. Cation-chloride cotransporters and neuronal function. Neuron. 2009;61:820–838. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee HH, Deeb TZ, Walker JA, Davies PA, Moss SJ. NMDA receptor activity downregulates KCC2 resulting in depolarizing GABAA receptor-mediated currents. Nat Neurosci. 2011;14:736–743. doi: 10.1038/nn.2806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mody I, De Koninck Y, Otis TS, Soltesz I. Bridging the cleft at GABA synapses in the brain. Trends Neurosci. 1994;17:517–525. doi: 10.1016/0166-2236(94)90155-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamann M, Rossi DJ, Attwell D. Tonic and spill-over inhibition of granule cells control information flow through cerebellar cortex. Neuron. 2002;14(33):625–633. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(02)00593-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitamura A, Ishibashi H, Watanabe M, Takatsuru Y, Brodwick M, Nabekura J. Sustained depolarizing shift of the GABA reversal potential by glutamate receptor activation in hippocampal neurons. Neurosci Res. 2008;62:270–277. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2008.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clarkson AN, Huang BS, MacIsaac SE, Mody I, Carmichael ST. Reducing excessive GABA-mediated tonic inhibition promotes functional recovery after stroke. Nature. 2010;468:305–309. doi: 10.1038/nature09511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.During MJ, Spencer DD. Extracellular hippocampal glutamate and spontaneous seizure in the conscious human brain. Lancet. 1993;341:1607–1610. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90754-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Song I, Savtchenko L, Semyanov A. Tonic excitation or inhibition is set by GABAA conductance in hippocampal interneurons. Nat Commun. 2011;2:376. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kononenko NI, Dudek FE. Mechanism of irregular firing of suprachiasmatic nucleus neurons in rat hypothalamic slices. 2003 J Neurophysiol. 2004;91:267–273. doi: 10.1152/jn.00314.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vida I, Bartos M, Jonas P. Shunting inhibition improves robustness of gamma oscillations in hippocampal interneuron networks by homogenizing firing rates. Neuron. 2006;49:107–117. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Szabadics J, Varga C, Molnár G, Oláh S, Barzó P, Tamás G. Excitatory effect of GABAergic axo-axonic cells in cortical microcircuits. Science. 2006;311:2335. doi: 10.1126/science.1121325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khirug S, Yamada J, Afzalov R, Voipio J, Khiroug L, Kaila K. GABAergic depolarization of the axon initial segment in cortical principal neurons is caused by the Na-K-2Cl cotransporter NKCC1. J Neurosci. 2008;28:4635–4639. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0908-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glickfeld LL, Roberts JD, Somogyi P, Scanziani M. Interneurons hyperpolarize pyramidal cells along their entire somatodendritic axis. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:21–23. doi: 10.1038/nn.2230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodruff A, Xu Q, Anderson SA, Yuste R. Depolarizing effect of neocortical chandelier neurons. Front Neural Circuits. 2009;3:15. doi: 10.3389/neuro.04.015.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klausberger T, Magill PJ, Márton LF, Roberts JD, Cobden PM, Buzsáki G, Somogyi P. Brain-state- and cell-type-specific firing of hippocampal interneurons in vivo. Nature. 2003;421:844–848. doi: 10.1038/nature01374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rivera C, Voipio J, Thomas-Crusells J, Li H, Emri Z, Sipilä S, et al. Mechanism of activity-dependent downregulation of the neuron-specific K-Cl cotransporter KCC2. J Neurosci. 2004;24:4683–4691. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5265-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khirug S, Huttu K, Ludwig A, Smirnov S, Voipio J, Rivera C, et al. Distinct properties of functional KCC2 expression in immature mouse hippocampal neurons in culture and in acute slices. Eur J Neurosci. 2005;21:899–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.03886.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lee HH, Walker JA, Williams JR, Goodier RJ, Payne JA, Moss SJ. Direct protein kinase C-dependent phosphorylation regulates the cell surface stability and activity of the potassium chloride cotransporter KCC2. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:29777–29784. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705053200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]