SUN–KASH nuclear envelope bridges formed by WIP and SUN proteins are present in the plant branch of the tree of life but have functionally diverged from their opisthokont counterparts and are involved in nuclear morphology and RanGAP–nuclear envelope association.

Abstract

Inner nuclear membrane Sad1/UNC-84 (SUN) proteins interact with outer nuclear membrane (ONM) Klarsicht/ANC-1/Syne homology (KASH) proteins, forming linkers of nucleoskeleton to cytoskeleton conserved from yeast to human and involved in positioning of nuclei and chromosomes. Defects in SUN–KASH bridges are linked to muscular dystrophy, progeria, and cancer. SUN proteins were recently identified in plants, but their ONM KASH partners are unknown. Arabidopsis WPP domain–interacting proteins (AtWIPs) are plant-specific ONM proteins that redundantly anchor Arabidopsis RanGTPase–activating protein 1 (AtRanGAP1) to the nuclear envelope (NE). In this paper, we report that AtWIPs are plant-specific KASH proteins interacting with Arabidopsis SUN proteins (AtSUNs). The interaction is required for both AtWIP1 and AtRanGAP1 NE localization. AtWIPs and AtSUNs are necessary for maintaining the elongated nuclear shape of Arabidopsis epidermal cells. Together, our data identify the first KASH members in the plant kingdom and provide a novel function of SUN–KASH complexes, suggesting that a functionally diverged SUN–KASH bridge is conserved beyond the opisthokonts.

Introduction

The nuclear envelope (NE) consists of an outer nuclear membrane (ONM) and an inner nuclear membrane (INM) that enclose the perinuclear space (PNS; Gerace and Burke, 1988). In nonplant eukaryotes, the ONM and INM are bridged by interactions between Klarsicht/ANC-1/Syne/Nesprin homology (KASH) and Sad1/UNC-84 (SUN) proteins (Razafsky and Hodzic, 2009; Graumann et al., 2010b; Starr and Fridolfsson, 2010). KASH proteins are integral membrane proteins of the ONM with a short C-terminal tail domain in the PNS. SUN proteins are INM proteins that contain at least one transmembrane domain (TMD) and a conserved C-terminal SUN domain in the PNS. The interaction of the KASH PNS tail with the SUN domain stably associates KASH proteins with the ONM (Padmakumar et al., 2005; Crisp et al., 2006; McGee et al., 2006).

Many SUN proteins interact with the nuclear lamins in the nucleoplasm, whereas KASH proteins interact with cytoskeleton or cytoskeleton-associated proteins. Thus, SUN–KASH interactions are part of a linker of nucleoskeleton to cytoskeleton complexes conserved from yeast to human, functioning in nuclei positioning and chromosome movement (Crisp et al., 2006). The founding members of SUN–KASH protein pairs have been identified in Caenorhabditis elegans. Interaction of the SUN protein UNC-84 with the actin-binding KASH protein ANC-1 is involved in nuclear anchorage; UNC-84 also interacts with the KASH protein UNC-83, which recruits kinesin-1 to transfer forces for nuclear migration (Horvitz and Sulston, 1980; Sulston and Horvitz, 1981; Malone et al., 1999). Similarly, the Schizosaccharomyces pombe SUN–KASH bridges, formed by Sad1 and Kms, transfer dynein motor forces to telomeres for positioning telomeres to the spindle pole body (Miki et al., 2004; Chikashige et al., 2006).

SUN proteins were recently identified in plants (Moriguchi et al., 2005; Graumann et al., 2010a; Murphy et al., 2010). The two Arabidopsis SUN proteins—AtSUN1 and AtSUN2—share the protein structure of the nonplant SUN proteins: an N-terminal domain containing an NLS, a TMD, a coiled-coil domain (CCD), and a SUN domain. Although both SUN proteins are ubiquitously expressed (Graumann et al., 2010a), a reported AtSUN1/AtSUN2 double mutant shows no phenotypes except for a nuclear shape change in root hairs (Oda and Fukuda, 2011). No plant KASH proteins were identified.

Arabidopsis WPP domain–interacting proteins (AtWIPs) are three plant-specific ONM proteins that redundantly anchor Arabidopsis RanGTPase–activating protein 1 (AtRanGAP1) to the NE (Xu et al., 2007). Here, we show that AtWIP1, AtWIP2, and AtWIP3 interact with AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 at the NE. The AtSUN–AtWIP1 interaction is required for the NE localization of AtWIP1 and AtRanGAP1 and for maintaining the elongated shape of plant nuclei. AtWIPs are the first identified plant KASH proteins, suggesting that SUN–KASH interactions are conserved beyond the opisthokonts but have functionally diverged.

Results and discussion

Identification of AtWIPs as ONM AtSUN–interacting partners

In most animal KASH proteins, the PNS tail terminates with a PPPX motif that is essential for SUN protein interaction and is required for NE localization of KASH proteins (Razafsky and Hodzic, 2009; Starr and Fridolfsson, 2010). WIPs are the only currently known plant ONM proteins with a C-terminal PNS tail, which terminates in a highly conserved ϕ-VPT motif (ϕ, hydrophobic amino acid; Xu et al., 2007). Deletion of the VVPT of AtWIP1 diminishes its NE localization (Xu et al., 2007). The AtWIP1 PNS tail has a low degree of similarity to known KASH domains (Fig. 1). It is significantly shorter than the tail of most KASH proteins but has similar length to that of C. elegans ZYG-12B and KDP-1 and Interaptin from Dictyostelium discoideum (Xiong et al., 2008; McGee et al., 2009; Minn et al., 2009). Specifically, the penultimate proline is highly conserved, and a terminal Ser/Thr residue is often present.

Figure 1.

Structural and sequence similarity between KASH domains and the PNS tail of AtWIP1. C termini of animal and fungal KASH proteins are aligned with the C terminus of AtWIP1. Extension of the TMD and the PNS tail are indicated below the alignment. ClustalX color is assigned to the alignment for convenient comparison. Ce, Caenorhabditis elegans; Dd, Dictyostelium discoideum; Dm, Drosophila melanogaster; Hs, Homo sapiens; Mm, Mus musculus; Sp, Schizosaccharomyces pombe.

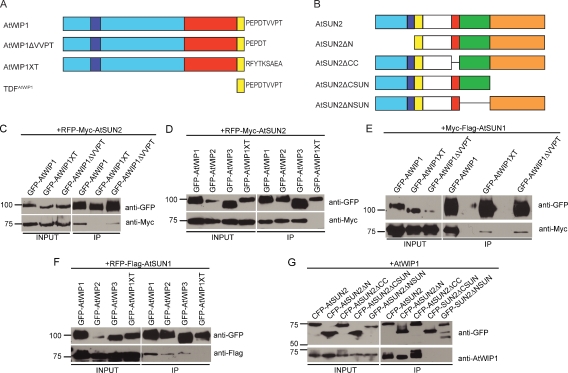

We tested the interaction between AtWIP1 and AtSUN2 by coimmunoprecipitation (co-IP). In the control protein GFP-AtWIP1XT (Fig. 2 A), the PNS tail of AtWIP1 (PEPDTVVPT) was replaced by the ER luminal tail (RFYTKSAEA) of tail-anchored cytochrome b5c from Aleurites fordii (Hwang et al., 2004). In addition, GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT (AtWIP1 without the VVPT motif; Fig. 2 A) was tested. AtSUN2 was C-terminally fused to an RFP-Myc tag (RFP-Myc-AtSUN2) and transiently coexpressed in Nicotiana benthamiana with GFP-AtWIP1, GFP-AtWIP1XT, or GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT. After IP with anti-GFP antibody, coimmunoprecipitated AtSUN2 was detected by anti-Myc antibody. GFP-AtWIP1 bound AtSUN2, whereas GFP-AtWIP1XT did not bind (Fig. 2 C). Deletion of the VVPT greatly diminished the interaction (Fig. 2 C). Thus, AtWIP1 interacts with AtSUN2, and the PNS tail of AtWIP1 is essential for the interaction. Deleting VVPT only partially affected the interaction, indicating that the less-conserved segment between VVPT and the TMD is also involved in binding AtSUN2.

Figure 2.

Characterization of AtSUN–AtWIP interactions. (A) Domain organization of AtWIP1 and mutant derivatives. AtWIP1 has an N-terminal domain with an unknown function (cyan), an NLS (blue), a CCD-binding AtRanGAP1 (red), a predicted TMD (yellow), and a PNS tail (shown in residues). (B) Domain organization of AtSUN2 and deletion constructs. AtSUN2 has an N-terminal domain with an unknown function (cyan), an NLS (blue), a TMD (yellow), an unknown domain (white), a CCD (red), and a SUN domain (here split to an N-terminal part [green] and a C-terminal part [orange]) (A and B) Figures are drawn to scale. (C) AtWIP1 interacts with AtSUN2 through its PNS tail. (D) AtWIP1, AtWIP2, and AtWIP3 interact with AtSUN2. (E) AtWIP1 interacts with AtSUN1 through its PNS tail. (F) AtWIP1, AtWIP2, and AtWIP3 interact with AtSUN1. (G) AtSUN2 interacts with AtWIP1 through its SUN domain. (C–G) GFP- or CFP-tagged proteins were immunoprecipitated and detected by anti-GFP antibody. RFP-Myc– or Myc-Flag–tagged proteins were detected by anti-Myc antibody, and RFP-Flag–tagged proteins were detected by anti-Flag antibody. The input/IP ratio is 1:10. Numbers on the left indicate molecular mass in kilodaltons.

Next, GFP-AtWIP2 and GFP-AtWIP3 were tested in co-IP assays with RFP-Myc-AtSUN2 alongside GFP-AtWIP1 and GFP-AtWIP1XT (Fig. 2 D). GFP-tagged AtWIP1, AtWIP2, and AtWIP3 coimmunoprecipitated AtSUN2, whereas GFP-AtWIP1XT did not, indicating that all three AtWIPs bind AtSUN2. To determine AtSUN1 binding, a Myc-Flag–tagged AtSUN1 (Myc-Flag-AtSUN1) was coimmunoprecipitated with GFP-AtWIP1, GFP-AtWIP1XT, and GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT (Fig. 2 E). After IP by the anti-GFP antibody, AtSUN1 was detected using anti-Myc antibody. Fig. 2 E shows that both the exchange of the PNS tail and the deletion of VVPT greatly reduced binding between AtWIP1 and AtSUN1. Fig. 2 F shows that GFP-AtWIP1, GFP-AtWIP2, and GFP-WIP3 all interact with RFP-Flag-AtSUN1. We conclude that all AtWIPs are binding partners of both AtSUNs and that the PNS tail of AtWIP1 is important for binding.

AtSUNs interact with AtWIP1 through their SUN domain

The SUN domain or the segment between the CCD and the SUN domain is required for interacting with known KASH proteins (Padmakumar et al., 2005; Stewart-Hutchinson et al., 2008). Protein sequence alignment shows that unlike animal and fungal SUN proteins, sequence conservation among plant SUN proteins begins immediately after the predicted CCD (Fig. S1). To test whether this extended plant SUN domain is required for binding WIPs, deletions of the N-terminal part of the SUN domain of AtSUN2 (P266-R309, denoted as AtSUN2ΔNSUN) and its C-terminal part (R310-A455, denoted as AtSUN2ΔCSUN; Figs. 2 B and S1) were tested along with CFP-AtSUN2, CFP-AtSUN2ΔN (deletion of the domain N terminal to the TMD; Fig. 2 B), and CFP-AtSUN2ΔCC (deletion of the CCD; Fig. 2 B) in co-IPs with AtWIP1. AtSUN2, AtSUN2ΔN, and AtSUN2ΔCC, but not GFP-AtSUN2ΔNSUN and CFP-AtSUN2ΔCSUN, bound AtWIP1 (Fig. 2 G). Hence, the SUN domain is essential for interacting with AtWIP1.

AtSUN1 affects the mobility of AtWIP1 at the plant NE

The mobility of a membrane protein will be reduced upon interacting with other proteins (Reits and Neefjes, 2001). To confirm that the SUN–WIP interaction occurs at the NE, we measured the mobility of AtWIP1-based fusion proteins using FRAP in the absence and presence of AtSUN-based fusion proteins. We examined the mobility of GFP-AtWIP1, GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT, and GFP-TDFAtWIP1 (the transmembrane domain fragment [TDF] is the TMD plus PNS tail; see Figs. 1 and 2 A) expressed transiently in N. benthamiana leaves and found that full-length GFP-AtWIP1 is the least mobile (Fig. 3 A). To quantify the mobility change, maximum recovery was compared. GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT is significantly more mobile than GFP-AtWIP1 (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 30), possibly because this deletion disrupts interactions of AtWIP1 and N. benthamiana SUN proteins. Interestingly, GFP-TDFAtWIP1 is also more mobile (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 30), indicating that the cytoplasmic N terminus of AtWIP1 is involved in binding interactions, possibly including RanGAP and WPP-interacting tail-anchored protein (Xu et al., 2007; Zhao et al., 2008).

Figure 3.

FRAP analysis of the interaction between AtWIP1 and AtSUN1. (A) Recovery curves of GFP-AtWIP1, GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT, and GFP-TDFAtWIP1. (B) Recovery curves of GFP-AtWIP1 coexpressed with RFP-Flag-AtSUN1 or RFP-Flag-AtSUN1ΔNSUN. (C) Recovery curves of GFP-AtWIP1 coexpressed with RFP-Myc-AtSUN2 or RFP-Myc-AtSUN2ΔNSUN. (D) Recovery curves of GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT coexpressed with RFP-Flag-AtSUN1 or RFP-Myc-AtSUN2. (E) Recovery curves of GFP-TDFAtWIP1 coexpressed with RFP-Flag-AtSUN1 or RFP-Myc-AtSUN2. (A–E) Error bars represent SEM (n = 60 for GFP-AtWIP1 in C; n = 30 for all others). Asterisks at the end of each curve indicate significant statistical difference of the maximum recovery compared with the green curve in each figure (P < 0.01, using a t test). Otherwise, no statistical difference has been observed (P > 0.05, using a t test).

When GFP-AtWIP1 was coexpressed with RFP-Flag-AtSUN1 (see Fig. S2 A for protein localization), a significant decrease (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 30) in mobility was detected (Fig. 3 B), indicating that AtSUN1 interacts with GFP-AtWIP1 at the NE. GFP-AtWIP1 is more mobile when coexpressed with RFP-Flag-AtSUN1ΔNSUN than with RFP-Flag-AtSUN1 (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 30) and has the same mobility as when expressed on its own (P > 0.05, using a t test; n = 30; Fig. 3 B). The same effects were observed when expressing GFP-AtWIP1 with either RFP-Myc-AtSUN2 (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 60 for GFP-AtWIP1 single expression; n = 30 for coexpression with RFP-Myc-AtSUN2) or with RFP-Myc-AtSUN2ΔNSUN (P > 0.05, using a t test; n = 60 for GFP-AtWIP1 single expression; n = 30 for coexpression with RFP-Myc-AtSUN2ΔNSUN; Fig. 3 C). When coexpressed with either RFP-Flag-AtSUN1 or RFP-Myc-AtSUN2, the mobility of GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT did not change (P > 0.05, using a t test; n = 30; Fig. 3 D), indicating that the mobility change requires the C-terminal VVPT motif. The mobility of the highly mobile GFP-TDFAtWIP1 also decreased when coexpressed with either RFP-Flag-AtSUN1 or GFP-Myc-AtSUN2 (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 30; Fig. 3 E). Together, these data corroborate the co-IP interaction results and show that both the NSUN domain and the VVPT motif are required for the interaction of AtWIP1 with AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 at the plant NE.

AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 are required to anchor AtWIP1 to the NE

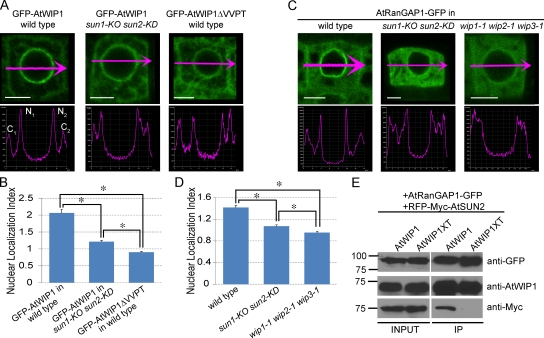

The NE localization of known KASH proteins depends on SUN proteins (Padmakumar et al., 2005; Crisp et al., 2006; Ketema et al., 2007; Stewart-Hutchinson et al., 2008). In GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT–transformed wild-type Arabidopsis, the GFP signal at the NE is significantly reduced compared with GFP-AtWIP1, and diffuse signal appears in the cytoplasm, consistent with the importance of VVPT for AtWIP1 NE localization (Xu et al., 2007). To test whether AtWIP1 NE localization requires SUN proteins, we transformed GFP-AtWIP1 into a sun1-KO sun2-KD mutant. The mutant contains two transfer DNA insertions that cause the complete absence of AtSUN1 transcript and a reduction in the amount of AtSUN2 transcript (Fig. S2 B). The GFP-AtWIP1 signal was imaged in undifferentiated root tip cells of three independent lines. Compared with GFP-AtWIP1 in wild type, the GFP-AtWIP1 signal in sun1-KO sun2-KD is predominantly diffuse in the cytoplasm, very similar to GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT in wild type (Fig. 4 A). For quantification, we defined an NE localization index (NLI) as the sum of the maximum from two NE intensities divided by the sum of the maximum cytoplasmic intensities ([N1 + N2]/[C1 + C2], as indicated in the wild-type intensity profile images in Fig. 4 A). A high NLI indicates a high concentration of the signal at the NE, and an NLI close to 1 indicates no apparent concentration. The NLI is significantly higher in GFP-AtWIP1–transformed wild type than in GFP-AtWIP1–transformed sun1-KO sun2-KD mutant and GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT–transformed wild type (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 50; Fig. 4, A and B). The difference between GFP-AtWIP1–transformed sun1-KO sun2-KD and GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT–transformed wild type likely reflects the fact that sun2-KD is not a null allele. These results indicate that AtSUNs are required for the concentration of AtWIP1 at the NE.

Figure 4.

AtSUNs are required for targeting AtWIP1 and AtRanGAP1 to the NE. (A) GFP-AtWIP1 or GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT signal in undifferentiated root cells (top row) and corresponding intensity profiles along the magenta arrows (bottom row). C1 and C2, cytoplasmic intensity 1 and 2, respectively; N1 and N2, nuclear intensity 1 and 2, respectively. Bars, 5 µm. (B) NLI ([N1 + N2]/[C1 + C2]) calculated using the intensities measured as shown in A. Asterisks indicate significant statistical difference between compared lines (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 50). Error bars represent SEM. (C) AtRanGAP1-GFP signal in undifferentiated root cells (top row) and corresponding intensity profiles along the magenta arrows (bottom row). Bars, 5 µm. (D) NLI calculated as described in B, using intensities measured as in C. Asterisks indicate significant statistical difference between compared lines (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 55). Error bars represent SEM. (E) AtSUN2, AtWIP1, and AtRanGAP1 are in the same complex. AtRanGAP1-GFP was immunoprecipitated and detected by anti-GFP antibody. AtWIP1 and RFP-Myc-AtSUN2 were detected with anti-AtWIP1 antibody and anti-Myc antibody, respectively. Numbers on the left indicate molecular mass in kilodaltons.

AtSUNs are required for AtRanGAP1 NE localization

In plants and animals, RanGAP is associated with the ONM, proposed to be important for efficient RanGTP hydrolysis during nucleocytoplasmic transport (Mahajan et al., 1997; Hutten et al., 2008). In animals, RanGAP is anchored by RanBP2 at the NE, whereas in Arabidopsis, AtWIPs are anchoring AtRanGAP at the NE in undifferentiated root cells (Xu et al., 2007; Meier et al., 2010). The loss of AtWIP1 at the NE in sun1-KO sun2-KD suggests that in plants, SUN proteins may play a role in RanGAP NE localization. Hence, we examined the GFP signal in undifferentiated root cells of AtRanGAP1-GFP–transformed sun1-KO sun2-KD lines (10 independent lines were examined) and compared it with AtRanGAP1-GFP–transformed wild type and wip1-1 wip2-1 wip3-1. The NLI was used to quantitatively compare the signals. The AtRanGAP1-GFP signal was significantly more diffuse in the cytoplasm in both mutants than in wild type (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 55; Fig. 4, C and D). Again, the higher NLI of sun1-KO sun2-KD than wip1-1 wip2-1 wip3-1 may be because sun2-KD is not a null allele.

AtWIP1 interacts with the WPP domain of AtRanGAP1 through its N-terminal cytoplasmic CCD (Xu et al., 2007), whereas AtSUN2 binds the PNS tail of AtWIP1. Thus, we tested whether AtSUN2 interacts with AtRanGAP1 through AtWIP1. AtRanGAP1-GFP and RFP-Myc-AtSUN2 were coexpressed with either AtWIP1 or AtWIP1XT in N. benthamiana leaves. Proteins were extracted and immunoprecipitated with anti-GFP antibody. The co-IP of AtWIP1 and AtWIP1XT was detected by anti-WIP1 antibody (Xu et al., 2007). Both AtWIP1 and AtWIP1XT were precipitated by AtRanGAP1-GFP (Fig. 4 E). However, coimmunoprecipitated RFP-Myc-AtSUN2, detected by anti-Myc antibody, was only present in the AtWIP1-coexpressed sample, indicating that AtSUN2 indirectly interacts with AtRanGAP1 through AtWIP1.

Thus, the SUN–WIP interaction functions in anchoring RanGAP to the plant NE. During mammalian mitosis, RanBP2 relocates to the kinetochores (KTs) and is required for the KT localization of RanGAP (Joseph et al., 2004). Although AtRanGAP1 is also localized to the KT, no plant RanBP2 homologues have been found. AtRanGAP1 has additional plant-specific mitotic localizations—the preprophase band that proceeds to the cortical division site during cell division—and these mitotic RanGAP localizations do not depend on WIPs (Xu et al., 2007). When AtSUN1 and AtSUN2 YFP fusions were imaged from prophase to metaphase in tobacco BY-2 suspension culture cells, they were absent from these mitotic sites (Fig. S2 C), suggesting that they are unlikely to be involved in the mitotic localization of plant RanGAP.

AtSUNs and AtWIPs are required for maintaining an elongated nuclear shape in epidermal cells

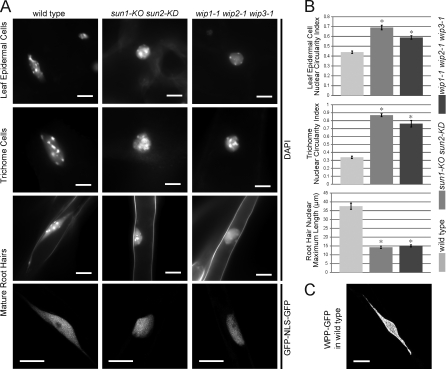

wip1-1 wip2-1 wip3-1 and sun1-KO sun2-KD have no developmental or fertility defects under laboratory conditions. A previously reported AtSUN1/AtSUN2 double mutant showed an increase in circularity of root hair cell nuclei (Oda and Fukuda, 2011). Thus, we investigated nuclear morphology in sun1-KO sun2-KD and wip1-1 wip2-1 wip3-1. As trichome nuclei and a portion of leaf epidermal cell nuclei are also elongated, we included these two cell types in this examination.

Imaging of DAPI fluorescence in fully expanded new leaves from plants before bolting showed that the nuclei of leaf epidermal cells and trichomes are significantly less elongated in both mutants (Fig. 5 A). To quantify nuclear circularity, the ratio of nuclear width to length was used. More elongated nuclei will have a lower circularity index, whereas round nuclei will have a circularity index close to 1. For consistency, the maximum cross section or a z-stacked image of each nucleus was used to calculate the circularity index. As shown in Fig. 5 B (top two histograms), wild type has a significantly lower circularity index than both mutants (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 60 for leaf epidermal cells; n = 20 for trichomes).

Figure 5.

Nuclear shape change in epidermal cells of sun1-KO sun2-KD and wip1-1 wip2-1 wip3-1 plants. (A) Comparison of nuclear shapes in trichomes, leaf epidermal cells, and mature root hair cells of wild type, sun1-KO sun2-KD, and wip1-1 wip2-1 wip3-1. Nuclei were DAPI stained, and mature root hair nuclei images in the bottom row are confocal maximum intensity projections using GFP-NLS-GFP as a nuclear marker. (B) Quantitative comparison of nuclear shape changes shown in A. Asterisks indicate significant statistical difference (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 60 for leaf epidermal cells; n = 20 for trichomes; n = 55 for root hairs) compared with wild type. Error bars represent SEM. (C) A confocal maximum intensity projection showing a super-elongated nucleus in a wild-type mature root hair using WPP-GFP as an NE marker. Bars, 10 µm.

Root hair nuclei were observed in DAPI-stained roots from 7–8-d-old seedlings. In wild type, DAPI staining revealed a super-elongated nuclear shape: a pod with two stretched thin tails extending from the poles (Fig. 5 A, third row). This super-elongated nuclear shape has not yet been reported but might be a variant of the fragmented and bilobed root hair nuclei observed by Chytilova et al. (2000). In sun1-KO sun2-KD and wip1-1 wip2-1 wip3-1 mutants, the pods were less elongated, and the tails were lost (Fig. 5 A). To quantify this change, we used the maximum length of a nucleus (including the tails). Fig. 5 B (bottom histogram) shows that wild-type nuclei are significantly more elongated than nuclei in both mutants (P < 0.01, using a t test; n = 55). The same nuclear shape changes were observed when nuclei were visualized by the GFP marker that represents the entire nucleoplasm (Fig. 5 A, bottom row). Fig. 5 C shows a WPP-GFP line (WPP domain of AtRanGAP1 fused with GFP, serving as an NE marker), illustrating that the super-elongated nuclear shape was also observed when the NE was labeled. Together, these data suggest that AtWIPs and AtSUNs are required to maintain the elongated or super-elongated nuclear shape in three different types of plant epidermal cells.

In animals, a predominant function of SUN–KASH bridges is to regulate nuclear position and migration through interactions with the cytoskeleton (Crisp et al., 2006). To investigate whether AtSUN–AtWIP interactions also affect nuclear positioning in Arabidopsis, two characterized nuclear positioning events were assayed. First, the position of the root hair nucleus is held at a specific distance from the growing tip by a process involving actin (Ketelaar et al., 2002). And second, the nucleus in a leaf hair (trichome) migrates to a fixed position close to the first branch point of the trichome cell (Folkers et al., 1997). Both processes were unchanged in both sun1-KO sun2-KD and wip1-1 wip2-1 wip3-1 (Fig. S3 and Videos 1, 2, and 3). This indicates that SUN–WIP interactions do not contribute significantly to nuclear positioning in root and leaf hairs.

The function of the elongated nuclear shape in plant epidermal cells is currently unknown, but it is conceivable that it might accommodate protection against mechanical stress or shearing forces of cytoplasmic streaming. Indeed, mammalian linker of nucleoskeleton to cytoskeleton complex components are implied in reduced nuclear mechanotransduction and the activation of mechanosensitive genes (Lammerding et al., 2004, 2005, 2006). In addition, nuclear shape changes have been correlated with both human disease and cell aging (Dahl et al., 2008; Webster et al., 2009). Laminopathies, such as Hutchinson–Gilford Progeria syndrome, are diseases caused by mutations in type A lamins. The nuclei of laminopathy patients often bear lobulated and invaginated nuclear shapes and changes in chromatin organization, leading to alteration in nuclear rigidity and sensitivity to mechanical stress. Similar nuclear shape changes occur during aging in C. elegans (Haithcock et al., 2005) and human cells (Scaffidi and Misteli, 2006). In plants, nuclear shape changes have also been observed in the leaf epidermal cells of Arabidopsis nucleoporin nup136 mutants (Tamura et al., 2010) and the root cells of Arabidopsis bearing mutations in long coiled-coil NE protein LITTLE NUCLEI1 and 2 (Dittmer et al., 2007). It will be important to determine the interaction of these proteins with the SUN–WIP complex described here and to develop assays that test the effect of mechanical stress on nuclear function in plant epidermal cells.

Materials and methods

Plant materials

Arabidopsis (Columbia ecotype) were grown at 25°C in soil under 16 h of light and 8 h of dark or on Murashige and Skoog plates (Caisson Laboratories, Inc.) under constant light. Mutant wip1-1 wip2-1 wip3-1 was previously reported (Xu et al., 2007). The sun1-KO sun2-KD mutant (SALK_123093 for sun1-KO and SALK_049398 for sun2-KD) was a gift from S. Armstrong and K. Osman (University of Birmingham, England, UK).

Constructs

WPP-GFP was previously reported as AtRanGAP1ΔC-GFP (Rose and Meier, 2001). In brief, the WPP domain of AtRanGAP1 was amplified by PCR using the primer 5′-GCCATGGATCATTCAGCGAAAACC-3′ and 5′-ACCCATGGCCTCAACCTCGGATTC-3′. The resulting PCR product was cloned into pCR II-TOPO and sequenced for confirmation before being cloned into the single NcoI site of pRTL2-mGFPS65T (von Arnim et al., 1998). Coding sequences of AtSUN2, AtSUN2ΔN, AtSUN2ΔCC, AtSUN2ΔCSUN, AtSUN1 without a stop codon, and AtSUN2 without a stop codon were amplified by PCR, cloned into the pDONR207 vector, and confirmed by sequencing. Coding sequences of AtRanGAP1, AtWIP1, TDFAtWIP1, AtWIP1ΔVVPT, AtWIP1XT, Flag-AtSUN1, Flag-AtSUN1ΔNSUN, Myc-AtSUN2, Myc-AtSUN2ΔNSUN, and NLS-GFP were amplified by PCR, cloned into the pENTR/D-TOPO vector (Invitrogen), and confirmed by sequencing. Coding sequences in pDONR207 or pENTR/D-TOPO vectors were moved to destination vectors by LR reaction (Invitrogen). AtRanGAP1 was cloned into pK7FWG2 (Karimi et al., 2002) to obtain AtRanGAP1-GFP; AtWIP1, TDFAtWIP1, AtWIP1ΔVVPT, AtWIP1XT, Myc-SUN2ΔNSUN, and NLS-GFP were cloned into pK7WGF2 (Karimi et al., 2002) to obtain GFP-AtWIP1, GFP-TDFAtWIP1, GFP-AtWIP1ΔVVPT, GFP-AtWIP1XT, GFP-SUN2ΔNSUN, and GFP-NLS-GFP; AtSUN2, AtSUN2ΔN, AtSUN2ΔCC, and AtSUN2ΔCSUN were moved to pB7WGC2 to obtain CFP-AtSUN2, CFP-AtSUN2ΔN, CFP-AtSUN2ΔCC, and CFP-AtSUN2ΔCSUN; AtSUN1 without a stop codon and AtSUN2 without a stop codon were moved to pCAMBIA1300 (Cambia) with a preinserted CaMV35Spromoter-CassetteA-eYFP-NOSterminator gateway fragment to obtain AtSUN1-YFP and AtSUN2-YFP. Flag-AtSUN1, Flag-AtSUN1ΔNSUN, Myc-AtSUN2, and Myc-AtSUN2ΔNSUN were cloned into pK7WGR2 (Karimi et al., 2002) to obtain RFP-Flag-AtSUN1, RFP-Flag-AtSUN1ΔNSUN, RFP-Myc-AtSUN2, and RFP-MycAtSUN2ΔNSUN; Flag-AtSUN1 was cloned into pGWB21 (Nakagawa et al., 2007) to obtain Myc-Flag-AtSUN1. AtWIP1 and AtWIP1XT were cloned to pH2GW7 (Karimi et al., 2002) to obtain the overexpressing constructs.

Transformation of Agrobacterium

The WPP-GFP construct was transformed to Agrobacterium LBA4404 by electroporation (Wise et al., 2006). Other expression constructs were transformed to Agrobacterium ABI by triparental mating (Wise et al., 2006). For triparental mating, in brief, the Escherichia coli carrying the constructs of interest were coincubated overnight at 30°C on Lysogeny broth agar (1.5%) plates with Agrobacterium ABI and the E. coli helper strain containing the vector pRK2013. Then, the bacterial mixture was streaked on Lysogeny broth agar (1.5%) plates with proper antibiotics to select transformed Agrobacterium.

Generation of transgenic plants

Transgenic Arabidopsis were obtained by Agrobacterium-mediated floral dip (Clough and Bent, 1998). In brief, Agrobacterium strains carrying the constructs of interest were inoculated in Lysogeny broth liquid medium and grown overnight at 30°C. The bacteria were collected by centrifuging and resuspended in transformation solution containing 5% sucrose and 300 µl/L silwet l-77 (Lehle Seeds) to OD600 = 0.8. The inflorescence part of Arabidopsis was dipped in the bacterial suspension. After being kept moist in the dark overnight at room temperature, the plants were moved to a growth chamber and allowed to set seeds. The transgenic plants were selected on Murashige and Skoog agar (0.8%) plates containing kanamycin or Basta (Sigma-Aldrich).

Co-IP experiments

Genes of interest were coexpressed transiently in N. benthamiana leaves by Agrobacterium infiltration (Sparkes et al., 2006). In brief, Agrobacterium cultures were collected by centrifuging and resuspended to OD600 = 1.0 in the infiltration buffer containing 10 mM MgCl2, 10 mM MES, pH 5.4, and 100 µM acetosyringone. The Agrobacterium suspension was pressure infiltrated into N. benthamiana leaves with a plastic syringe. Plants were grown for 3 d after infiltration. Leaves were collected and ground in liquid nitrogen into a fine powder before co-IP was performed at 4°C. For samples involving Myc-Flag-AtSUN1, radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% SDS, 0.5% NaDeoxycholate, 1% NP-40, 1 mM PMSF, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) was used. Other protein extracts were prepared in NP-40 buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1 mM EDTA, 3 mM DTT, 1 mM PMSF, and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich). Protein complexes were immunoprecipitated from extracts by anti-GFP antibody (ab290; Abcam) bound to protein A–Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). The immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-AtWIP1 (1:2,000; Xu et al., 2007), anti-GFP (1:2,000, 632569; Takara Bio Inc.), anti-Myc (1:1,000, M5546; Sigma-Aldrich), or anti-FLAG (1:2,000, F7425; Sigma-Aldrich) antibody.

DAPI staining and nuclear length measurement

For leaf nuclear staining, fully expanded leaves before bolting were cut into small pieces. For root hair nuclear DAPI staining, 7- or 8-d-old Arabidopsis seedlings grown on Murashige and Skoog plates were used. All samples were stained in 1 µg/ml DAPI solution for 20 min. Images were collected with a digital camera (DS-Qi1Mc; Nikon). The length of the nuclei was measured using NIS-Elements software (Nikon).

Root hair and trichome nuclear positioning assay

Young root hairs of 11-d-old Arabidopsis seedlings carrying the GFP-NLS-GFP marker were imaged using a confocal microscope (Eclipse C90i; Nikon). For the trichome nuclear positioning assay, the nuclei of fully expanded young leaves of 25-d-old plants were imaged using a digital camera (DS-Qi1Mc), and distances were measured using NIS-Elements software.

Confocal microscopy and FRAP

A confocal microscope (Eclipse C90i) with minimum or medium aperture was used to image 7- or 8-d-old Arabidopsis seedlings. Intensities were measured using NIS-Elements software. Cytoplasmic intensities shown in Fig. 4 (C1 and C2) were measured close to the cell wall to capture maximal cytoplasmic values away from more central vacuoles. To reduce noise, intensity profiles shown in Fig. 4 were calculated by averaging the intensities of the adjacent 4 pixels. For FRAP, infiltrated Nicotiana tobacco leaf sections were examined with a confocal microscope (LSM 510; Carl Zeiss). Samples were preincubated in 4 µM latrunculin B (Sigma-Aldrich) for 20 min to stop nuclei movement. Bleaching parameters were identical for all FRAP experiments, including use of a 63× oil immersion lens, a digital zoom factor of two, and a 21-µm2 circular bleach area. The argon laser output was kept at 50% at all times. For image acquisition, the 488-nm laser transmission was set to <4%. For bleaching, the laser transmission was increased to 100%. Each sample was scanned five times before bleach, and after bleach, each sample was scanned for 42 s with a 0.5-s time interval. For data analysis, the raw fluorescence intensity data were normalized to a percentage scale using the equation IN = 100 × (IT − IMIN)/(IMAX − IMIN), in which IN is the normalized fluorescence intensity, IT is the fluorescence intensity at a given time point, IMIN is the lowest fluorescence intensity immediately after the bleach, and IMAX is the mean prebleach fluorescence intensity (Graumann et al., 2007). The normalized data were fitted with a curve using Prism 4 (GraphPad Software), and statistical analysis was performed using Excel (Microsoft) and GraphPad software.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows plant-specific conserved residues in plant SUN domains revealed by the alignment of SUN domains from different species. Fig. S2 shows AtWIP1 and AtSUN localization and characterization of sun1-KO sun2-KD. Fig. S3 shows that the nuclear position in root hairs and trichomes is not affected in sun1-KO sun2-KD and wip1-1 wip2-1 wip3-1. Video 1 shows nuclear movement from the trichome baseline to the first branch point in a wild-type trichome. Video 2 shows nuclear movement from the trichome baseline to the first branch point in a sun1-KO sun2-KD trichome. Video 3 shows nuclear movement from the trichome baseline to the first branch point in a wip1-1 wip2-1 wip3-1 trichome. Online supplemental material is available at http://www.jcb.org/cgi/content/full/jcb.201108098/DC1.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Dr. Susan Armstrong and Dr. Kim Osman for the gift of their unpublished sun1-KO sun2-KD mutant.

This work was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation to I. Meier and by the Leverhulme Trust (F/00382/H) to D.E. Evans.

Footnotes

Abbreviations used in this paper:

- CCD

- coiled-coil domain

- INM

- inner nuclear membrane

- IP

- immunoprecipitation

- KT

- kinetochore

- NE

- nuclear envelope

- NLI

- NE localization index

- ONM

- outer nuclear membrane

- PNS

- perinuclear space

- TDF

- transmembrane domain fragment

- TMD

- transmembrane domain

References

- Chikashige Y., Tsutsumi C., Yamane M., Okamasa K., Haraguchi T., Hiraoka Y. 2006. Meiotic proteins bqt1 and bqt2 tether telomeres to form the bouquet arrangement of chromosomes. Cell. 125:59–69 10.1016/j.cell.2006.01.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chytilova E., Macas J., Sliwinska E., Rafelski S.M., Lambert G.M., Galbraith D.W. 2000. Nuclear dynamics in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Biol. Cell. 11:2733–2741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough S.J., Bent A.F. 1998. Floral dip: A simplified method for Agrobacterium-mediated transformation of Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 16:735–743 10.1046/j.1365-313x.1998.00343.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crisp M., Liu Q., Roux K., Rattner J.B., Shanahan C., Burke B., Stahl P.D., Hodzic D. 2006. Coupling of the nucleus and cytoplasm: Role of the LINC complex. J. Cell Biol. 172:41–53 10.1083/jcb.200509124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahl K.N., Ribeiro A.J., Lammerding J. 2008. Nuclear shape, mechanics, and mechanotransduction. Circ. Res. 102:1307–1318 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.173989 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer T.A., Stacey N.J., Sugimoto-Shirasu K., Richards E.J. 2007. LITTLE NUCLEI genes affecting nuclear morphology in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 19:2793–2803 10.1105/tpc.107.053231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folkers U., Berger J., Hülskamp M. 1997. Cell morphogenesis of trichomes in Arabidopsis: Differential control of primary and secondary branching by branch initiation regulators and cell growth. Development. 124:3779–3786 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerace L., Burke B. 1988. Functional organization of the nuclear envelope. Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 4:335–374 10.1146/annurev.cb.04.110188.002003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann K., Irons S.L., Runions J., Evans D.E. 2007. Retention and mobility of the mammalian lamin B receptor in the plant nuclear envelope. Biol. Cell. 99:553–562 10.1042/BC20070033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann K., Runions J., Evans D.E. 2010a. Characterization of SUN-domain proteins at the higher plant nuclear envelope. Plant J. 61:134–144 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2009.04038.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graumann K., Runions J., Evans D.E. 2010b. Nuclear envelope proteins and their role in nuclear positioning and replication. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38:741–746 10.1042/BST0380741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haithcock E., Dayani Y., Neufeld E., Zahand A.J., Feinstein N., Mattout A., Gruenbaum Y., Liu J. 2005. Age-related changes of nuclear architecture in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:16690–16695 10.1073/pnas.0506955102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvitz H.R., Sulston J.E. 1980. Isolation and genetic characterization of cell-lineage mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics. 96:435–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutten S., Flotho A., Melchior F., Kehlenbach R.H. 2008. The Nup358-RanGAP complex is required for efficient importin α/β-dependent nuclear import. Mol. Biol. Cell. 19:2300–2310 10.1091/mbc.E07-12-1279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang Y.T., Pelitire S.M., Henderson M.P.A., Andrews D.W., Dyer J.M., Mullen R.T. 2004. Novel targeting signals mediate the sorting of different isoforms of the tail-anchored membrane protein cytochrome b5 to either endoplasmic reticulum or mitochondria. Plant Cell. 16:3002–3019 10.1105/tpc.104.026039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joseph J., Liu S.-T., Jablonski S.A., Yen T.J., Dasso M. 2004. The RanGAP1-RanBP2 complex is essential for microtubule-kinetochore interactions in vivo. Curr. Biol. 14:611–617 10.1016/j.cub.2004.03.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karimi M., Inzé D., Depicker A. 2002. GATEWAY vectors for Agrobacterium-mediated plant transformation. Trends Plant Sci. 7:193–195 10.1016/S1360-1385(02)02251-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketelaar T., Faivre-Moskalenko C., Esseling J.J., de Ruijter N.C., Grierson C.S., Dogterom M., Emons A.M. 2002. Positioning of nuclei in Arabidopsis root hairs: An actin-regulated process of tip growth. Plant Cell. 14:2941–2955 10.1105/tpc.005892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ketema M., Wilhelmsen K., Kuikman I., Janssen H., Hodzic D., Sonnenberg A. 2007. Requirements for the localization of nesprin-3 at the nuclear envelope and its interaction with plectin. J. Cell Sci. 120:3384–3394 10.1242/jcs.014191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammerding J., Schulze P.C., Takahashi T., Kozlov S., Sullivan T., Kamm R.D., Stewart C.L., Lee R.T. 2004. Lamin A/C deficiency causes defective nuclear mechanics and mechanotransduction. J. Clin. Invest. 113:370–378 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammerding J., Hsiao J., Schulze P.C., Kozlov S., Stewart C.L., Lee R.T. 2005. Abnormal nuclear shape and impaired mechanotransduction in emerin-deficient cells. J. Cell Biol. 170:781–791 10.1083/jcb.200502148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lammerding J., Fong L.G., Ji J.Y., Reue K., Stewart C.L., Young S.G., Lee R.T. 2006. Lamins A and C but not lamin B1 regulate nuclear mechanics. J. Biol. Chem. 281:25768–25780 10.1074/jbc.M513511200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan R., Delphin C., Guan T., Gerace L., Melchior F. 1997. A small ubiquitin-related polypeptide involved in targeting RanGAP1 to nuclear pore complex protein RanBP2. Cell. 88:97–107 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81862-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malone C.J., Fixsen W.D., Horvitz H.R., Han M. 1999. UNC-84 localizes to the nuclear envelope and is required for nuclear migration and anchoring during C. elegans development. Development. 126:3171–3181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee M.D., Rillo R., Anderson A.S., Starr D.A. 2006. UNC-83 IS a KASH protein required for nuclear migration and is recruited to the outer nuclear membrane by a physical interaction with the SUN protein UNC-84. Mol. Biol. Cell. 17:1790–1801 10.1091/mbc.E05-09-0894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGee M.D., Stagljar I., Starr D.A. 2009. KDP-1 is a nuclear envelope KASH protein required for cell-cycle progression. J. Cell Sci. 122:2895–2905 10.1242/jcs.051607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meier I., Zhou X., Brkljacić J., Rose A., Zhao Q., Xu X.M. 2010. Targeting proteins to the plant nuclear envelope. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 38:733–740 10.1042/BST0380733 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miki F., Kurabayashi A., Tange Y., Okazaki K., Shimanuki M., Niwa O. 2004. Two-hybrid search for proteins that interact with Sad1 and Kms1, two membrane-bound components of the spindle pole body in fission yeast. Mol. Genet. Genomics. 270:449–461 10.1007/s00438-003-0938-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minn I.L., Rolls M.M., Hanna-Rose W., Malone C.J. 2009. SUN-1 and ZYG-12, mediators of centrosome-nucleus attachment, are a functional SUN/KASH pair in Caenorhabditis elegans. Mol. Biol. Cell. 20:4586–4595 10.1091/mbc.E08-10-1034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moriguchi K., Suzuki T., Ito Y., Yamazaki Y., Niwa Y., Kurata N. 2005. Functional isolation of novel nuclear proteins showing a variety of subnuclear localizations. Plant Cell. 17:389–403 10.1105/tpc.104.028456 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy S.P., Simmons C.R., Bass H.W. 2010. Structure and expression of the maize (Zea mays L.) SUN-domain protein gene family: Evidence for the existence of two divergent classes of SUN proteins in plants. BMC Plant Biol. 10:269 10.1186/1471-2229-10-269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T., Kurose T., Hino T., Tanaka K., Kawamukai M., Niwa Y., Toyooka K., Matsuoka K., Jinbo T., Kimura T. 2007. Development of series of gateway binary vectors, pGWBs, for realizing efficient construction of fusion genes for plant transformation. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 104:34–41 10.1263/jbb.104.34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oda Y., Fukuda H. 2011. Dynamics of Arabidopsis SUN proteins during mitosis and their involvement in nuclear shaping. Plant J. 66:629–641 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2011.04523.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padmakumar V.C., Libotte T., Lu W., Zaim H., Abraham S., Noegel A.A., Gotzmann J., Foisner R., Karakesisoglou I. 2005. The inner nuclear membrane protein Sun1 mediates the anchorage of Nesprin-2 to the nuclear envelope. J. Cell Sci. 118:3419–3430 10.1242/jcs.02471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Razafsky D., Hodzic D. 2009. Bringing KASH under the SUN: The many faces of nucleo-cytoskeletal connections. J. Cell Biol. 186:461–472 10.1083/jcb.200906068 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reits E.A.J., Neefjes J.J. 2001. From fixed to FRAP: Measuring protein mobility and activity in living cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 3:E145–E147 10.1038/35078615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose A., Meier I. 2001. A domain unique to plant RanGAP is responsible for its targeting to the plant nuclear rim. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 98:15377–15382 10.1073/pnas.261459698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scaffidi P., Misteli T. 2006. Lamin A-dependent nuclear defects in human aging. Science. 312:1059–1063 10.1126/science.1127168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes I.A., Runions J., Kearns A., Hawes C. 2006. Rapid, transient expression of fluorescent fusion proteins in tobacco plants and generation of stably transformed plants. Nat. Protoc. 1:2019–2025 10.1038/nprot.2006.286 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr D.A., Fridolfsson H.N. 2010. Interactions between nuclei and the cytoskeleton are mediated by SUN-KASH nuclear-envelope bridges. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol. 26:421–444 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart-Hutchinson P.J., Hale C.M., Wirtz D., Hodzic D. 2008. Structural requirements for the assembly of LINC complexes and their function in cellular mechanical stiffness. Exp. Cell Res. 314:1892–1905 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.02.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulston J.E., Horvitz H.R. 1981. Abnormal cell lineages in mutants of the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev. Biol. 82:41–55 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90427-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K., Fukao Y., Iwamoto M., Haraguchi T., Hara-Nishimura I. 2010. Identification and characterization of nuclear pore complex components in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell. 22:4084–4097 10.1105/tpc.110.079947 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Arnim A.G., Deng X.W., Stacey M.G. 1998. Cloning vectors for the expression of green fluorescent protein fusion proteins in transgenic plants. Gene. 221:35–43 10.1016/S0378-1119(98)00433-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webster M., Witkin K.L., Cohen-Fix O. 2009. Sizing up the nucleus: Nuclear shape, size and nuclear-envelope assembly. J. Cell Sci. 122:1477–1486 10.1242/jcs.037333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise A.A., Liu Z., Binns A.N. 2006. Three methods for the introduction of foreign DNA into Agrobacterium. Methods Mol. Biol. 343:43–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong H., Rivero F., Euteneuer U., Mondal S., Mana-Capelli S., Larochelle D., Vogel A., Gassen B., Noegel A.A. 2008. Dictyostelium Sun-1 connects the centrosome to chromatin and ensures genome stability. Traffic. 9:708–724 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00721.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu X.M., Meulia T., Meier I. 2007. Anchorage of plant RanGAP to the nuclear envelope involves novel nuclear-pore-associated proteins. Curr. Biol. 17:1157–1163 10.1016/j.cub.2007.05.076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Q., Brkljacic J., Meier I. 2008. Two distinct interacting classes of nuclear envelope-associated coiled-coil proteins are required for the tissue-specific nuclear envelope targeting of Arabidopsis RanGAP. Plant Cell. 20:1639–1651 10.1105/tpc.108.059220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]