Abstract

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) is an extracellular lipid mediator that regulates nervous system development and functions through multiple types of LPA receptors. Here we explore the role of LPA receptor subtypes in cortical astrocyte functions. Astrocytes cultured under serum-free conditions were found to express the genes of five LPA receptor subtypes, lpa1 to lpa5. When astrocytes were treated with dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate, a reagent inducing astrocyte differentiation or activation, lpa1 expression levels remained unchanged, but those of other LPA receptor subtypes were relatively reduced. LPA stimulated DNA synthesis in both undifferentiated and differentiated astrocytes, but failed to do so in astrocytes prepared from mice lacking lpa1 gene. LPA also inhibited [3H]-glutamate uptake in both undifferentiated and differentiated astrocytes; and LPA-induced inhibition of glutamate uptake was still observed in lpa1-deficient astrocytes. Taken together, these observations demonstrate that LPA1 mediates LPA-induced stimulation of cell proliferation but not inhibition of glutamate uptake in astrocytes.

1. Introduction

Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) is an extracellular lipid mediator produced by platelets and present in serum (Moolenaar, 1999). LPA-induced cellular responses include enhanced cell proliferation, cytoskeletal rearrangement, and reduced cell death, depending on cell type. These effects are mediated through G protein–coupled LPA receptors. To date, five types of LPA receptor genes (lpa1–lpa5) have been identified, and lpa1, lpa2, and lpa3 are known to be structurally related with over 50% amino acid identity (Fukushima et al., 2001; Ishii et al., 2004). Recently identified LPA receptor subtypes lpa4 (GPR23) and lpa5 (GPR92) share ~35% amino acid identity and are phylogenically distant from lpa1, lpa2 and lpa3 (Noguchi et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2006). All five LPA receptor genes are expressed in developing and adult brains, suggesting involvement in cellular functions of neural cells. Indeed, lpa1 has been shown to be involved in neuronal differentiation in developing cerebral cortex (Kingsbury et al., 2003; Fukushima et al., 2007).

Recently, LPA was shown to induce diverse cellular responses in cultured astrocytes, which express lpa1, lpa2 and lpa3 genes (Rao et al., 2003; Sorensen et al., 2003). These responses include cell proliferation, inhibition of glutamate uptake and increased production of radicals, all which relate to neurodegeneration (Keller et al., 1996; Keller et al., 1997; Rao et al., 2003; Sorensen et al., 2003), although there are some conflicting reports (Fuentes et al., 1999; Pebay et al., 1999). However, it is unclear which LPA receptor subtype is involved in these LPA-induced astrocyte responses. Moreover, whether recently identified lpa4 and lpa5 are expressed in astrocytes remains unknown. Here we examine the expression profiles of LPA receptor subtypes in cultured astrocytes and explore the role of LPA receptors in astrocyte proliferation and glutamate uptake in culture.

2. Experimental procedures

2.1. Astrocyte cultures

Astrocytes were prepared from cerebral cortices of postnatal day 1 ICR mice (SLC, Japan), or lpa1 heterozygous (lpa1 (+/−)) or lpa1 homozygous (lpa1 (−/−)) mice (Contos et al., 2000). Pups from lpa1 (+/−) females crossed with lpa1 (+/−) males were genotyped by PCR using genomic DNA prepared from tail tissue. These lpa1 (+/−) mice were of C57BL/6N background (backcrossed 5 generations). Cerebral cortices were dissected and dissociated with 0.25% trypsin/0.1 mM EDTA. Cortical cells were plated in T75 flasks or T25 flasks (cells from 1 mouse/25 cm2) and cultured to confluence in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Wako Pure Chemicals, Osaka, Japan) containing 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). Cells were then harvested with trypsin/EDTA, replated in 24-well plates, and cultured in 10% FCS-containing DMEM for 1 day. Cells were further cultured in serum-free Opti-MEM (Invitrogen, Tokyo, Japan) and subjected to assay. Between 80 and 90% of the cells were glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP)-positive by immunocytochemical staining using anti-GFAP antibody (Dr. Watanabe, Hokkaido University). The ratios of microglia, oligodendrocytes, and neurons were less than 5, 1, and 1%, respectively.

2.2. RT-PCR

Total RNA was prepared from cultured astrocytes using Tri Reagent (Sigma. St. Louis. MO) and treated with RNase-free DNase; cDNAs were synthesized using an oligo(dT) primer (all reagents from Invitrogen). The resultant cDNAs (0.025 μg) were amplified by PCR using GoTaq green master mix (Promega, Tokyo, Japan) for LPA receptor family members. The primers (Nippon EGT, Toyama, Japan) used were: for lpa1, forward lpa1-s3 (5′-AGTTCTGGACCCAGGAGGAATCGG-3′) and reverse lpa1-as3 (5′-ACTTCTCATAGGCCAGGACATCGCA-3′), producing a 157-bp product; for lpa2, lpa2-s2 (5′-CACTCAGCCTAGTCAAGACGGTT-3′) and lpa2-as2 (5′-GCATCTCGGCAGGAATATACCACT-3′), producing a 193-bp product; for lpa3, lpa3-s1 (5′-GGTGGCGGTATACGTACGCATCT-3′) and lpa3-as1 (5′-ACGTGTTGCACGTTACACTGCTTG-3′), producing a 216-bp product; for lpa4, lpa4-s1 (5′-TGGTGACACCCTCTGTAAGATCTC-3′) and lpa4-as1 (5′-GGAGAAGCCTTCAAAGCAAGTGG-3′), producing a 262-bp product; for lpa5, lpa5-s1 (5′-GGTGAGCGTGTACATGTGCA-3′) and lpa5-as1 (5′-GCTGCCGTACATGTTCATCTGG-3′), producing a 157-bp product. The cycling protocol was performed as follows: 60 s at 95°C; 33 cycles of 20 s at 95°C, 20 s at 56°C, and 40 s at 72°C; and a final extension period of 7 min at 72°C. These conditions were sufficient for semi-quantitative detection of all LPA receptor subtype genes. The absence of genomic DNA contamination was confirmed by using other primers for lpa1 that span the intron.

2.3. [3H]-Thymidine incorporation assay

Astrocytes were treated with [3H]-thymidine (0.5 μCi/ml; American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) in Opti-MEM for 4 h, washed with ice-cold PBS, and solubilized with 200 μl of 0.2 M NaOH. Lysates were transferred to a 1.5-ml tube and mixed with 40 μl of 1 M HCl and 60 μl of 100% trichloroacetic acid (TCA). DNA was precipitated by centrifugation at 15,000 x g and washed twice with 5% TCA, solubilized with 0.1 M NaOH, and measured for radioactivity using a scintillation counter.

2.4. [3H]-Glutamate uptake assay

Astrocytes were treated with 100 μM [3H]-glutamate (0.2 μCi/ml; American Radiolabeled Chemicals, St. Louis, MO) in Opti-MEM for 30 min, washed twice with ice-cold Opti-MEM, and lysed with 100 μl of lysis buffer. Radioactivity of the lysates was measured using a scintillation counter.

2.5. Materials

Oleoyl-LPA was purchased from Avanti Polar Lipid (Alabaster, AL), dissolved in sterile H2O at 10 mM and stored at −30 ºC until use. Fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (FAFBSA) was purchased from Sigma, and stored at 10% (w/v) in sterile phosphate-buffered saline at −30 ºC. Dibutyryl cyclic adenosine monophosphate (DBcAMP) was purchased from Nacalai Tesque Chemicals (Kyoto, Japan), dissolved in sterile H2O at 100 mM, and stored at −30 ºC until use. Pertussis toxin, PD98059, wortmannin, and Y27632 were from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA).

2.6. Statistics

Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by a post hoc test was applied to data to determine statistical significance by using the statistical software, StatView 4.5 (Abacus Concepts, Berkeley, CA).

3. Results and Discussion

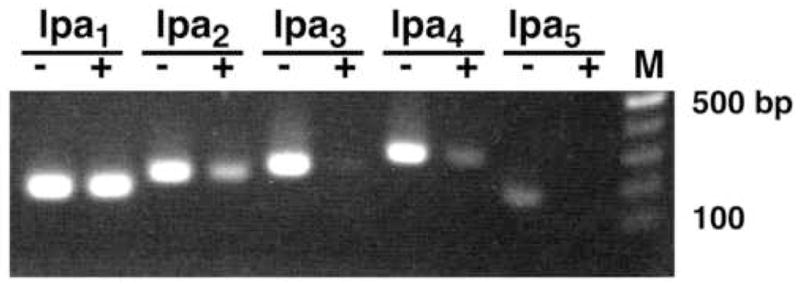

Astrocytes have long been known to respond to cAMP-elevating reagents with stellate morphology and increased expression of GFAP, indicating astrocyte differentiation. The stellate morphology also resembles that of reactive astrocytes in vivo (Sensenbrenner et al., 1980). We, therefore, examined the gene expression of LPA receptor family members in both undifferentiated and differentiated (DBcAMP-treated) astrocytes. Astrocytes were cultured under serum-free conditions, because serum contains LPA at μM levels that may affect LPA receptor gene expression. RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that genes of each LPA receptor subtype (lpa1~ lpa5) were expressed in undifferentiated astrocytes, although the lpa5 signal was barely visible under these conditions (Fig. 1). Treatment of astrocytes with DBcAMP induced a stellate morphology in most cells and raised GFAP expression (data not shown), indicating these astrocytes were differentiated, as previously reported (Sensenbrenner et al., 1980). In these differentiated astrocytes, the lpa1 expression level remained unchanged (Fig. 1). In contrast, the expression of lpa2 and lpa4 were reduced, and those of lpa3 and lpa5 became undetectable (Fig. 1). Thus, astrocyte differentiation may result in alterations in LPA receptor gene expression. Alternatively, it is also possible that DBcAMP-mediated intracellular signaling influences the promoter activities of these genes with the exception of lpa1.

Figure 1.

LPA receptor genes are expressed in cultured astrocytes and altered by DBcAMP treatment. Astrocytes were cultured in the absence (−) or presence (+) of 1 mM DBcAMP for 4 days. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR for LPA receptor subtypes. M, 100 bp DNA ladder.

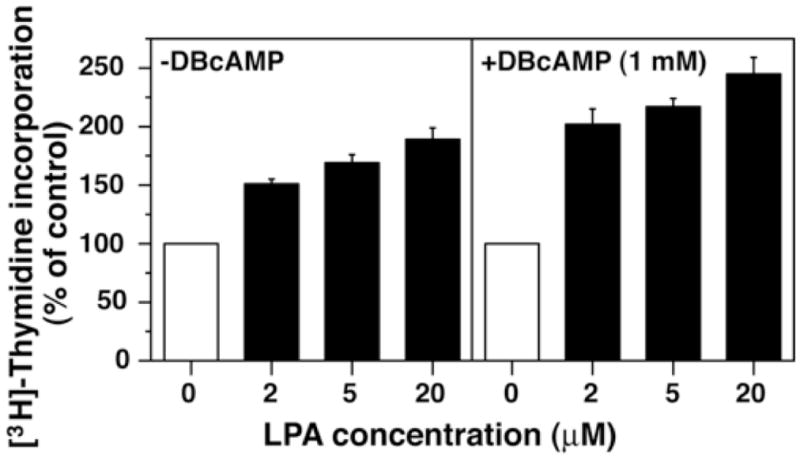

We next examined the effects of LPA on DNA synthesis in astrocytes. Undifferentiated astrocytes responded to LPA in a concentration-dependent manner with an increase in [3H]-thymidine incorporation into DNA (Fig. 2), in accordance with previous reports (Tabuchi et al., 2000; Rao et al., 2003; Sorensen et al., 2003). In differentiated astrocytes, LPA also exerted similar concentration-dependent effects on DNA synthesis (Fig. 2). Considering the constant level of lpa1 expression observed in undifferentiated and differentiated astrocytes, this result suggests that LPA1 primarily mediates the LPA-induced stimulation of DNA synthesis.

Figure 2.

LPA stimulates DNA synthesis in cultured astrocytes. Astrocytes were cultured in the absence or presence of 1 mM DBcAMP for 3 days. Cells were further cultured with varying concentrations of LPA for 18 hr and subjected to [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. Fatty acid-free bovine serum albumin (FAFBSA, 0.05%) was used as a vehicle. The averages of incorporated radioactivity were 1,027 ± 24 and 393 ± 40 cpm/well in undifferentiated and differentiated astrocytes, respectively. Data are means ± S.E.M. from triplicate determinations of the representative experiment.

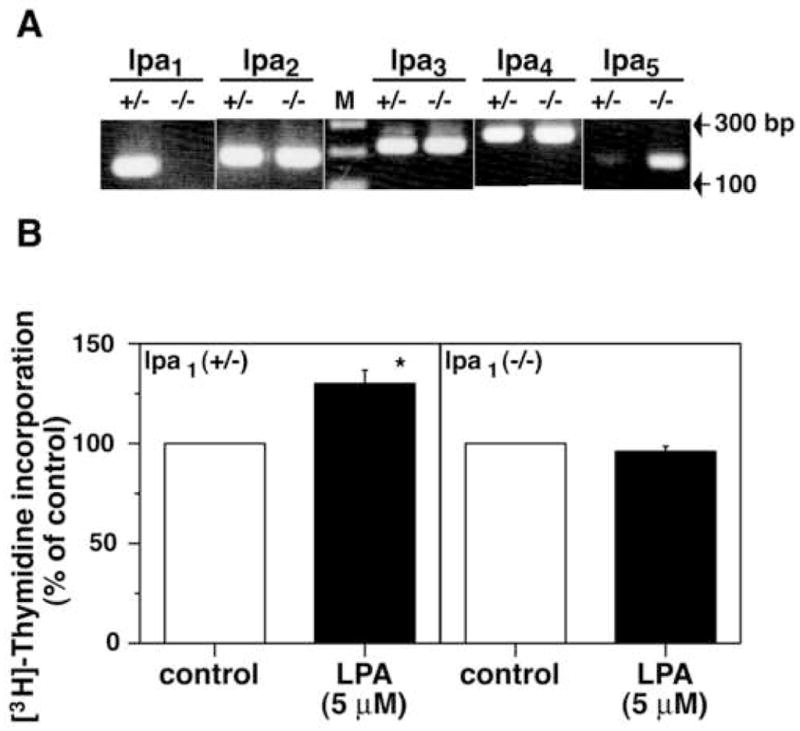

To investigate this issue directly, we prepared astrocyte cultures from lpa1(−/−) mice and examined the effects of LPA on DNA synthesis. As expected, these astrocytes lacked lpa1 expression and showed gene expression of lpa2, lpa3 and lpa4 at levels comparable to those in astrocytes derived from lpa1(+/−) (Fig. 3A). lpa 5expression appeared to be relatively increased in lpa1(−/−) astrocytes, although the reason for this remains unknown. Enhancement of DNA synthesis by LPA was completely lost in lpa1(−/−) astrocytes (Fig. 3B). Thus, these results strongly suggest that LPA-induced stimulation of DNA synthesis in astrocytes is mediated through LPA1. Because LPA-induced increase in astrocyte proliferation was shown to be pertussis toxin-sensitive (Keller et al., 1997; Tabuchi et al., 2000), the LPA1-Gi/o pathway is a likely mechanism for this response. In addition, because lpa1(−/−) astrocytes grew well in serum-containing medium and in a manner indistinguishable from that of wild-type astrocytes (data now shown), it appears that lpa1 is unnecessary for intrinsic astrocyte growth in culture.

Figure 3.

LPA-stimulated DNA synthesis in astrocytes is mediated through LPA1. A) RT-PCR analyses for LPA receptor gene expression in astrocytes derived from lpa1 heterozygous (+/−) or homozygous (−/−) mice. Astrocytes prepared from lpa1 (+/−) or lpa1 (−/−) mice were cultured in serum-free medium for 3 days. Total RNA was extracted and subjected to RT-PCR. M, 100 bp DNA ladder. B) Effects of LPA on DNA synthesis in astrocytes derived from lpa1 (+/−) or lpa1 (−/−) mice. Astrocytes prepared from lpa1 (+/−) and lpa1 (−/−) were cultured in serum-free medium for 2 days. Cells were further cultured with or without 5 μM LPA for 18 hr and subjected to [3H]-thymidine incorporation assay. FAFBSA (0.05%) was used as a vehicle. The averages of incorporated radioactivity were 988 ± 104 and 808 ± 67 cpm/well in lpa1 (+/−) and lpa1 (−/−) astrocytes, respectively. Data are means ± S.E.M. from three to four independent experiments. *, p < 0.05.

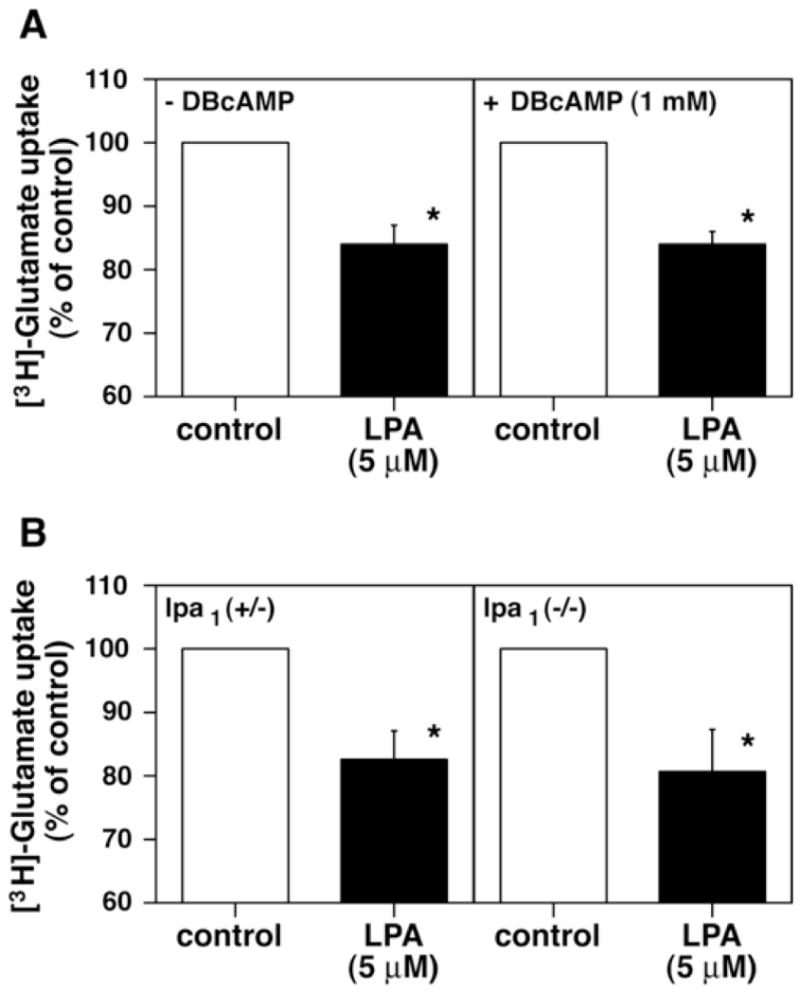

An important role of astrocytes is the regulation of extracellular glutamate concentrations which can be neurotoxic at high concentrations (Gegelashvili and Schousboe, 1997; Schousboe and Waagepetersen, 2005). This regulation is primarily accomplished by uptake of glutamate through glutamate transporters expressed in astrocytes. Undifferentiated astrocytes express GLAST, a subtype of glutamate transporter, while differentiated astrocytes express both GLAST and GLT-1, another subtype of the transporter (Swanson et al., 1997; Schlag et al., 1998). LPA was previously reported to inhibit glutamate uptake by astrocytes (Keller et al., 1996; Keller et al., 1997). Thus, we examined the effects of LPA on glutamate uptake in both undifferentiated and differentiated astrocytes. Pretreatment of cells with LPA resulted in an approximately 16% reduction in glutamate uptake (Fig. 4A). Inhibition of glutamate uptake by LPA treatment was also observed to a degree similar to that in undifferentiated astrocytes (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

LPA inhibits glutamate uptake independently of LPA1. A) Effects of LPA on [3H]-glutamate uptake in cultured astrocytes. Astrocytes were cultured in the absence or presence of 1 mM DBcAMP under serum-free conditions for 3 days, and subjected to [3H]-glutamate incorporation assay. The levels of incorporated glutamate in undifferentiated and differentiated cells were 22,321 ± 485 and 22,926 ± 1182 cpm/well, respectively. B) Effect of LPA on [3H]-glutamate uptake in cultured astrocytes prepared from lpa1 (+/−) or lpa1 (−/−) mice. Astrocytes cultures were prepared from lpa1 (+/−) or lpa1 (−/−) mice, and subjected to [3H]-glutamate incorporation assay. The levels of incorporated glutamate in undifferentiated and differentiated cells were 29,558 ± 1327 and 22,502 ± 1286 cpm/well, respectively. Data are means ± S.E.M. from three to four independent experiments. *, p < 0.05.

To examine the involvement of LPA1 in glutamate uptake, lpa1(−/−) astrocytes were used for the same assay. LPA exposure resulted in 19% inhibition of glutamate uptake in lpa1(−/−) astrocytes, which was equivalent to that (17% inhibition) observed in lpa1(+/−) astrocytes (Fig. 4B). Taken together, these results indicated that LPA-induced inhibition of glutamate uptake is not mediated through LPA1. lpa3 is undetectable in differentiated astrocytes; therefore, lpa2, lpa4, lpa5 or other unidentified LPA receptor might be involved in glutamate uptake inhibition by LPA.

We further explored the intracellular signaling pathways through which LPA inhibits glutamate uptake. LPA2, LPA4 and LPA5 activate one or more of Gi/o, Gq and G12/13-mediated pathways (Ishii et al., 2000; Noguchi et al., 2003; Lee et al., 2006), leading to stimulation of divergent signaling molecules, such as MAP kinase, phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K), or Rho kinase. We tested the effects of pertussis toxin (a Gi/o inhibitor), PD98059 (a MAP kinase inhibitor), wortmannin, (a PI3K inhibitor), and Y27632 (a Rho kinase inhibitor). Although these reagents blocked their corresponding kinase-dependent responses in other cell types employed in our laboratory, each of them failed to inhibit the effects of LPA on glutamate uptake in both undifferentiated and differentiated astrocytes (data not shown). Thus, the signaling pathways are yet to be determined, and identification of the LPA receptor and signaling pathways as well as involvement of non-receptor mechanisms are currently underway.

To date, lpa1 expression has been observed in oligodendrocytes but not astrocytes in adult brains (Weiner et al., 1998; Stankoff et al., 2002). However, astrocytes respond to LPA with astrogliosis, reflecting astrocyte proliferation leading to glial scar formation, when LPA is directly injected into mouse brains (Sorensen et al., 2003). This finding suggests that astrocyte expression of LPA receptor genes in normal brains is undetected using typical assay conditions for in situ hybridization. Alternatively, LPA receptor gene expression may be induced upon physical or LPA stimulation in astrocytes in vivo. Although neural cells are one source of LPA production in the brain (Fukushima et al., 2000), platelets are known to produce high levels of LPA in serum (Eichholtz et al., 1993; Tigyi et al., 1995). If platelet-derived LPA enters the brain due to impairment of the blood-brain barrier following brain injury or ischemia (Eichholtz et al., 1993; Tigyi et al., 1995), LPA-induced astrocyte responses, such as glutamate uptake inhibition and cell proliferation, may induce neuronal cell death or accelerate neurodegeneration triggered by other stimuli, such as glutamate. Further investigation of the roles of LPA receptor in astrocyte responses would benefit our understanding of neuropathology and help develop medicinal treatments for neurodegenerative diseases.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Masahiko Watanabe (Hokkaido University) for providing the anti-GFAP antibody, and Yuka Morita, Yuri Tanaka, Yumi Ohbo and Ayumi Kawakami for technical assistance. This work was supported by the Ministry of Education, Culture, and Science, Japan; a grant from Kyowa Hakko Industry Co.; the Akiyama Science Foundation; the Ono Foundation; the Suzuken Memorial Foundation; and a Kinki University Research Grant (RK17-027).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Contos JJA, Fukushima N, Weiner JA, Kaushal D, Chun J. Requirement for the lpA1 lysophosphatidic acid receptor gene in normal suckling behavior. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:13384–13389. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.24.13384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eichholtz T, Jalink K, Fahrenfort I, Moolenaar WH. The bioactive phospholipid lysophosphatidic acid is released from activated platelets. Biochem J. 1993;291:677–680. doi: 10.1042/bj2910677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuentes E, Nadal A, McNaughton PA. Lysophospholipids trigger calcium signals but not DNA synthesis in cortical astrocytes. Glia. 1999;28:272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima N, Ishii I, Contos JA, Weiner JA, Chun J. Lysophospholipid receptors. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 2001;41:507–534. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.41.1.507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima N, Shano S, Moriyama R, Chun J. Lysophosphatidic acid stimulates neuronal differentiation of cortical neuroblasts through the LPA(1)-G(i/o) pathway. Neurochem Int. 2007;50:302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.neuint.2006.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukushima N, Weiner JA, Chun J. Lysophosphatidic acid (LPA) is a novel extracellular regulator of cortical neuroblast morphology. Dev Biol. 2000;228:6–18. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gegelashvili G, Schousboe A. High affinity glutamate transporters: regulation of expression and activity. Mol Pharmacol. 1997;52:6–15. doi: 10.1124/mol.52.1.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii I, Contos JJ, Fukushima N, Chun J. Functional comparisons of the lysophosphatidic acid receptors, LPA1/VZG-1/EDG-2, LPA2/EDG-4, and LPA3/EDG-7 in neuronal cell lines using a retrovirus expression system. Mol Pharmacol. 2000;58:895–902. doi: 10.1124/mol.58.5.895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishii I, Fukushima N, Ye X, Chun J. Lysophospholipid receptors: signaling and biology. Annu Rev Biochem. 2004;73:321–354. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.73.011303.073731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller JN, Steiner MR, Holtsberg FW, Mattson MP, Steiner SM. Lysophosphatidic acid-induced proliferation-related signals in astrocytes. J Neurochem. 1997;69:1073–1084. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1997.69031073.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller JN, Steiner MR, Mattson MP, Steiner SM. Lysophosphatidic acid decreases glutamate and glucose uptake by astrocytes. J Neurochem. 1996;67:2300–2305. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67062300.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kingsbury MA, Rehen SK, Contos JJ, Higgins CM, Chun J. Non-proliferative effects of lysophosphatidic acid enhance cortical growth and folding. Nat Neurosci. 2003;6:1292–1299. doi: 10.1038/nn1157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee CW, Rivera R, Gardell S, Dubin AE, Chun J. GPR92 as a new G12/13 and Gq coupled lysophosphatidic acid receptor that increases cAMP: LPA5. J Biol Chem. 2006 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603670200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moolenaar WH. Bioactive lysophospholipids and their G protein-coupled receptors. Exp Cell Res. 1999;253:230–238. doi: 10.1006/excr.1999.4702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noguchi K, Ishii S, Shimizu T. Identification of p2y9/GPR23 as a novel G protein-coupled receptor for Lysophosphatidic acid, structurally distant from the Edg family. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:25600–25606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M302648200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pebay A, Torrens Y, Toutant M, Cordier J, Glowinski J, Tence M. Pleiotropic effects of lysophosphatidic acid on striatal astrocytes. Glia. 1999;28:25–33. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(199910)28:1<25::aid-glia3>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao TS, Lariosa-Willingham KD, Lin FF, Palfreyman EL, Yu N, Chun J, Webb M. Pharmacological characterization of lysophospholipid receptor signal transduction pathways in rat cerebrocortical astrocytes. Brain Res. 2003;990:182–194. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03527-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlag BD, Vondrasek JR, Munir M, Kalandadze A, Zelenaia OA, Rothstein JD, Robinson MB. Regulation of the glial Na+-dependent glutamate transporters by cyclic AMP analogs and neurons. Mol Pharmacol. 1998;53:355–369. doi: 10.1124/mol.53.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schousboe A, Waagepetersen HS. Role of astrocytes in glutamate homeostasis: implications for excitotoxicity. Neurotox Res. 2005;8:221–225. doi: 10.1007/BF03033975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sensenbrenner M, Devilliers G, Bock E, Porte A. Biochemical and ultrastructural studies of cultured rat astroglial cells: effect of brain extract and dibutyryl cyclic AMP on glial fibrillary acidic protein and glial filaments. Differentiation. 1980;17:51–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.1980.tb01081.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen SD, Nicole O, Peavy RD, Montoya LM, Lee CJ, Murphy TJ, Traynelis SF, Hepler JR. Common signaling pathways link activation of murine PAR-1, LPA, and S1P receptors to proliferation of astrocytes. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;64:1199–1209. doi: 10.1124/mol.64.5.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankoff B, Barron S, Allard J, Barbin G, Noel F, Aigrot MS, Premont J, Sokoloff P, Zalc B, Lubetzki C. Oligodendroglial expression of Edg-2 receptor: developmental analysis and pharmacological responses to lysophosphatidic acid. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20:415–428. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson RA, Liu J, Miller JW, Rothstein JD, Farrell K, Stein BA, Longuemare MC. Neuronal regulation of glutamate transporter subtype expression in astrocytes. J Neurosci. 1997;17:932–940. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-03-00932.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tabuchi S, Kume K, Aihara M, Shimizu T. Expression of lysophosphatidic acid receptor in rat astrocytes: mitogenic effect and expression of neurotrophic genes. Neurochem Res. 2000;25:573–582. doi: 10.1023/a:1007542532395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tigyi G, Hong L, Yakubu M, Parfenova H, Shibata M, Leffler CW. Lysophosphatidic acid alters cerebrovascular reactivity in piglets. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:H2048–2055. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1995.268.5.H2048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiner JA, Hecht JH, Chun J. Lysophosphatidic acid receptor gene vzg-1/lpA1/edg-2 is expressed by mature oligodendrocytes during myelination in the postnatal murine brain. J Comp Neurol. 1998;398:587–598. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]