Abstract

G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) are the largest family of cell surface receptors regulating multiple cellular processes. β-adrenergic receptor (βAR) is a prototypical member of GPCR family and has been one of the most well-studied receptors in determining regulation of receptor function. Agonist activation of βAR leads to conformational change, resulting in coupling to G protein and generating cAMP as secondary messenger. The activated βAR is phosphorylated resulting in binding of β-arrestin that physically interdicts further G protein coupling leading to receptor desensitization. The phosphorylated βAR is internalized and undergoes resensitization by dephosphorylation mediated by protein phosphatase 2A in the early endosomes. Desensitization and resensitization are two sides of the same coin maintaining the homeostatic functioning of the receptor. While significant interest has revolved around understanding mechanisms of receptor desensitization little is known about resensitization. In our current review we provide an overview on regulation of βAR function with a special emphasis on receptor resensitization and its functional relevance in the context of fine tuning receptor signaling.

Key words: G protein-coupled receptors, β-adrenergic receptors, desensitization, resensitization, phosphoinositide-3-kinase, protein phosphatase 2A, G protein coupled receptor kinases, β-arrestin

Introduction

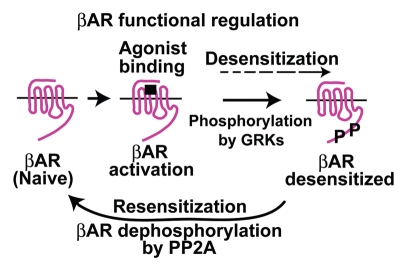

β-adrenergic receptors (βARs) belong to a large family of cell surface receptors known as G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs).1 GPCRs are seven transmembrane (TM) membrane proteins that transduce extracellular stimuli into secondary messengers inside the cell providing the required informational input for cellular responses. GPCRs are critical regulators of cellular function as they transduce diverse array of chemical and sensory stimuli like light, odor, taste, neurotransmitters and hormones.2 Activation of GPCR is classically known to activate G protein which activates the effector secondary messenger. Recent studies have shown that in addition to the classical G protein activation, GPCR activation sets into motion a series of events that are more appreciated. The molecular events ensuing activation of GPCRs in addition to G protein coupling involves (Fig. 1) (1) feed back phosphorylation of the receptor to diminish second messenger generation,3 (2) initiate G protein-independent signaling4 and (3) commence GPCR endocytosis that brings about receptor dephosphorylation and resensitization.5 Appreciation of these set of complex events and clear balance in this process indicates that receptor function is a finely tuned process. Dysregulation in any one of these events would result in alteration of receptor function and intracellular signaling output. The current review will elaborate on the various molecular events that regulate receptor function using βARs as a proto-typical member of the large GPCR family. Importantly, the molecular events with respect to receptor activation, phosphorylation, G protein-independent signaling and desensitization are well-studied and have been comprehensively reviewed in references 2–4 and 6. In contrast, little is known about mechanisms regulating resensitization. An indepth understanding of resensitization is important as alterations in resensitization could also contribute toward receptor dysfunction similar to the other components regulating receptor function (like desensitization and internalization). Therefore in our current review, we provide a brief overview on mechanisms of βAR signaling and desensitization that sets the receptor up for resensitization. This is followed by an indepth overview of the current understanding of mechanisms regulating βAR resensitization. Furthermore, as little is known about contribution of receptor resensitization to pathology, we provide a general outline of potential role of resensitization in disease states.

Figure 1.

An overview on regulation of βAR function.

βAR Signaling

β1 and β2ARs are the most well-studied members of the βAR family comprising of three members; β1, β2 and β3ARs. βARs are one of the most powerful regulators of cardiac function among the estimated 200 GPCRs in the heart. In addition to heart, they are also expressed in kidney, central nervous system, adipocytes, bronchial and vascular smooth muscle cells, lymphocytes, endothelial cells and hepatocytes.7,8 Consistent with their expression and role in numerous tissues, βARs were one of the first target receptors for rational drug design.7 βAR agonist or antagonists are among the oldest and most commonly prescribed therapeutic agents for management of heart failure and asthma.3,9,10 βARs are activated by endogenous catecholamines epinephrine/norepinephrine and binding of these receptors on cardiomyocytes results in positive inotropic and chronotropic responses.3 In addition to the classical role of βARs in regulating cellular physiology, there is growing body of evidence showing that norepinephrine stimulation of βAR elevates proliferation of cancer cells.11 Such a role for βARs is supported by the studies showing that β-blocker treatment significantly reduced breast cancer metastasis, recurrence and mortality.12 In view of evolving role of βARs in new pathologies, it becomes all the more pertinent to better understand the regulation of βAR function and signaling.

Agonist binding to βAR results in a conformational change leading to receptor coupling to Gsα subtype of hetero-trimeric G protein. Gsα is the adenylyl cyclase (AC) stimulatory G protein resulting in generation of cAMP in the cells. Increase in cellular concentration of cAMP leads to enhanced cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) activity which mediates functional consequences of Gs-coupled receptor activation. A well-established functional consequence of cAMP-mediated PKA activation is mobilization of Ca2+ mediating the cardiac contraction meeting the demands of increased cardiac output.3 Although similar downstream signaling events exist in the airway smooth muscle cells, PKA activation mediates relaxation by phosphorylation of proteins involved in Ca2+ sensitivity and cross bridge cycling.13 Normally, all the members of the βAR family couple to the Gsα G protein but under certain conditions couple to AC inhibitory G protein Giα subtype.14 Coupling of βARs to either Gsα or Giα allows for release of the Gβγ subunits of the hetero-trimeric G protein which provides a mechanism for amplification of the signals from the activated receptor. Such a view is well-appreciated as ligand binding to βAR activates myriad of signaling proteins and there are several excellent reviews that overview the pathways that regulate multitude of cellular responses.2,3,15 In addition to these classical mechanisms of βAR signaling, recent studies have shown that activated βAR provides a platform for the assembly and activation of signaling cascades including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathways that are primarily regulated by a scaffolding protein β-arrestin that is recruited to the activated receptors.4,16

Desensitization of βARs

Once the cell manifests an extracellular signal into a cellular response, the initiated signal within the cell needs to be dampened or shut off despite the presence of the stimuli. Cells have developed elaborate mechanism to turn off the activated βAR and mechanistically it involves (Fig. 1)(1) desensitization (uncoupling) of GPCR/G protein signaling mediated by phosphorylation of βAR, (2) recruitment of β-arrestin that physically interdicts further βAR-G protein coupling and (3) endocytosis of GPCRs into endosomes. The functional uncoupling of activated βAR from its cognate G protein occurs by phosphorylation of the receptor by second messenger (cAMP) activated kinases like PKA or PKC17 and G protein coupled receptor kinases (GRKs).17 In this context, PKA or PKC whether activated as a consequence of βAR stimulation (homologous desensitization) or via other GPCRs (heterologous desensitization) can phosphorylate βARs to reduce G protein coupling.18 Differential regulation indicates that GRKs mediate phosphorylation of agonist occupied βAR while PKA/PKC can phosphorylate βARs independent of their occupancy or activity status.14,18

Phosphorylation of agonist occupied βARs by GRKs results in recruitment of β-arrestin to the receptor complex.17 There are seven members of the GRK family (GRK 1–7) of which GRK 2, 3, 5 and 6 are ubiquitously expressed and mediate agonist dependent βAR phosphorylation recruiting β-arrestin to the receptor. Among the GRKs, GRK 2 and 3 are recruited to the activated βAR complex by Gβγ subunits of the dissociated hetero-trimeric G protein while GRK 5 and 6 are associated with the plasma membrane.19

Recruitment of β-arrestin to agonist occupied βAR following GRK phosphorylation not only sterically hinders G protein coupling but also prepares the receptor toward internalization.20 In addition, β-arrestin also initiates G protein-independent signaling.4,16 It is important to note in this context, that βAR belongs to class A family of receptors wherein recruited β-arrestin falls off the βAR complex prior to internalization.20 While, β-arrestin remains bound to the GPCRs of class B family (e.g., angiotensin II type 1A receptor) and is internalized along with the receptor into early endosomes.20 Despite the transient nature of β-arrestin interaction with βAR, it plays a critical role in linking desensitized receptors to the endocytic machinery.21 Internalized βARs are directed to recycling endosomes wherein, they are dephosphorylated and recycled back to the plasma membrane as naïve receptors ready for new stimulation (resensitized) or trafficked to lysosomes for degradation.1,21 In addition to the critical role of β-arrestin in receptor function, β-arrestin through its scaffolding function provides a platform for formation of multifunctional signaling cascades. These cascades or signalsomes can initiate a variety of cellular responses through MAPKs, Src tyrosine kinase, nuclear factor κB (NFκB) and phosphoinositide-3-kinase (PI3K).15

In addition to the above mentioned classical mechanisms of βAR desensitization, it is also known that under certain conditions like inflammation and oxidative stress βARs are predisposed toward elevated dysfunction. Studies in cardiomyocytes as well as human airway smooth muscle cells have shown that the pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNFα, IL-1β and IL-13 significantly pre-dispose βARs toward desensitization.22,23 Studies in neonatal myocytes have shown that TNFα alone is sufficient to induce βAR desensitization and potential mechanism of dysfunction seems to be proximal to βAR upstream of adenylyl cyclase.23 Furthermore, studies in human airway smooth muscle cells have shown that TNFβ treatment pre-disposes the cell towards βAR dysfunction and reduced relaxation.13 Despite this knowledge, underlying mechanisms of βAR dysfunction mediated by TNFα is currently not known. Similarly, multiple potential mechanisms mediating βAR desensitization have been put forward for IL-1β and IL-13 in the human airway smooth muscle cells13 showing that less is understood on the cytokine-βAR cross-talk. We believe this is an important area wherein time and resources need to be invested to close the knowledge gap as inflammation is major factor in conditions like hypertension, diabetes, obesity and dyslipidemia which may potentially contribute toward βAR dysfunction. This is important as currently little is known about the pro-inflammatory cytokines mediated βAR dysfunction in these conditions.

In this context, oxidative stress is another important component in many of the above mentioned co-morbid conditions24–26 and role of oxidative stress on βAR function is an emerging area. Evidence suggests that reactive oxygen species (ROS) plays an important role in mediating adrenergic function.27,28 Increased ROS production following βAR activation via the NADPH oxidase not only contributes to altering downstream signals but on a feed back loop that modulates receptor phosphorylation and internalization.29 Such specific feed back role of cellular redox is possible due to their ability to impart “on-off ” switches through oxidative/nitrosative modification of various regulator proteins26,30,31 and may potentially also include receptors. Such modification in the components of the βAR desensitization pathway is well-known32,33 to contribute toward altered receptor function. In this context, it has been shown that multiple components of the βAR desensitization and internalization machinery are nitrosylated in a dynamic manner. Nitrosylation of GRK2 inhibits βAR phosphorylation reducing desensitization and downregulation of βARs32 and dynamin nitrosylation results in enhanced internalization.34 Furthermore, it is also known that β-arrestin acts as a scaffolding protein for eNOS recruiting eNOS to the receptor complex. This mediates dynamin nitrosylation and receptor internalization.33 Thus, these processes have significant implication in receptor function and we believe that like a kinase-phosphatase systems, ROS dependent oxidative-nitrosative switches may critically play an important role in βAR desensitization-resensitization.

Resensitization of βARs

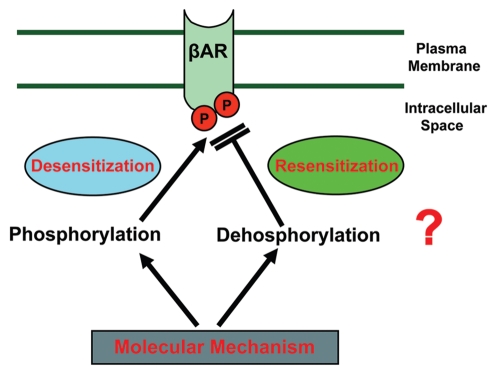

Functional status of βAR is dynamically regulated by its ability to perceive signals and transmit them into the cells. This dynamic balance is maintained by the fine tuning of βAR desensitization (phosphorylation) and resensitization (dephosphorylation) (Fig. 2). Resensitization can be defined as a process that restores the responsiveness of the desensitized receptor either in the continued presence or absence of desensitizing stimulus.35 In the overall scheme of receptor dynamics, βAR resensitization is as important as desensitization because it maintains tissue homeostasis as receptor become refractory to responding to their environment upon desensitization.36 Even though we have narrowed the definition of resensitization as the process of βAR dephosphorylation, it needs to be appreciated that there are multiple steps prior to this process and alteration in any of these steps may have implications on receptor resensitization. For instance, following dynamin mediated pinching of the clathrin vesicle, receptor containing vesicle could be transported as a recycling endosome or targeted to lysosomal mediated degradation. It is well-known that multiple processes regulate dynamin function and nitrosylation being one of them.34 Studies have shown that inhibition of nitrosylation of dynamin results in significant reduction in βAR internalization in turn affecting resensitization. Transport of the endocytosed βAR to an appropriate location for resensitization vs. lysosomal degradation also contributes to the overall resensitization efficiency in a cell. The transport/movement of the vesicles is dependent on acute local actin synthesis and reorganization37,38 and alteration of this process may lead to improper localization of the endocytosed receptor. The molecules that modulate the localization of these vesicles to specific regions in the cell are the small Rab GTPases which are critical to the formation of recycling early endosomes in which resensitization occurs.39,40 In addition to these effectors, receptor recycling is also altered by scaffolding proteins that specifically harbor the PDZ domain.

Figure 2.

Receptor desensitization (phosphorylation) and resensitization (dephosphorylation) a balancing act maintaining homeostasis of βAR function.

Majority of GPCRs including βARs contain carboxyl-terminal motifs that strongly interacts with PDZ containing scaffolding proteins like PSD-95, MAGI-2 and GIPC that recruit and alter the processes of receptor internalization and signaling.41 Post synaptic density protein PSD-95 binding to β1ARs results in inhibition of receptor internalization which in turn affects the processes regulating resensitization. Importantly, mutation in the PSD-95 binding PDZ domain of β1AR results in changes in internalization properties of β1AR that also alters the cardiac myocyte contraction properties indicating a critical role for this protein in regulating receptor function.42,43 In contrast, binding of PDZ domain on β1AR by MAGI-3 initiated unique signaling pattern but did not alter internalization41 suggesting that binding of PDZ domain on the receptor by different PDZ containing scaffolding proteins will elicit a specific itinerary of trafficking for the receptor. For example binding of the PDZ domain of the receptor by SAP-97-AKAP-79-cAMP-dependent protein kinase scaffold regulates efficient recycling.44 Thus the role of PDZ sequence in regulating βAR function is only beginning to be appreciated and with time the critical role of PDZ-containing protein in mediating receptor trafficking and in turn resensitization will be better understood. These studies show that steps prior to the actual dephosphorylation event are important, but in no way diminish the importance βAR dephosphorylation in the process of receptor resensitization.

In terms of βAR resensitization, it is believed that once internalized, the receptors undergo dephosphorylation in the early endosomes by protein phosphates 2A (PP2A)45 and are recycled back to the plasma membrane.3 βAR dephosphorylation is dependent on acidification of the receptor containing early endosomes as it is thought that acidification allows for effective PP2A function.45 Several studies in this respect have observed that sequestered receptors in the endosomal compartments are less phosphorylated than desensitized receptors on the plasma membrane.46,47 Furthermore, isolated vesicles containing sequestered receptors showed higher phosphatase activity than the plasma membrane. These observations suggested that internalization was required for dephosphorylation and functional resensitization laying foundation to the paradigm that dephosphorylation occurred in the endosomes and not at the plasma membrane.45,47–50

Although the paradigm that receptor internalization is required for resensitization may be the norm, there may be conditions wherein the receptor may not follow this set pathway toward resensitization. Some of the earliest studies51 found that despite blocking internalization with inhibitors, these inhibitors could not block receptor resensitization. Even though the findings were provocative, interpretation of the data was difficult as the tools available to investigators did not provide evidence that resensitization could occur at the plasma membrane. But with availability of new tools especially antibodies that can recognize βAR phosphorylation either by PKA or GRK52,53 provides strength for better interpretation of the resensitization studies. In this regard, inhibition of phosphorylated βAR internalization by hypertonic sucrose or expression of a dominant-negative dynamin still resulted in dephosphorylation of βAR at GRK and PKA sites.53,54 Studies using low concentrations of βAR agonist (isoprenaline, 300 pM) that does not cause receptor internalization have shown that βAR can still undergo dephosphorylation following selective PKA site phosphorylation.53,54 Capitalizing on differences in the agonist dependence on PKA and GRK phosphorylation, studies have shown that dephosphorylation of PKA site occurs at the plasma membrane under conditions precluding agonist-induced GRK phosphorylation, β-arrestin binding or internalization.55 Despite inhibiting βAR internalization, agonist treatment had little effect on the GRK site dephosphorylation. Interestingly, in these conditions, resensitization measured by adenylyl cyclase activity occurred more rapidly than the measured rates of GRK and PKA site dephosphorylation.55 These recent studies open the question regarding the link between βAR internalization and resensitization. In this regard, in vivo studies on isolated trachea show that short-term desensitization of βAR is incomplete due to concurrent balancing act of resensitization that continuously restores the responsiveness of desensitizing βARs.35 This brings into context the idea that internalization and resensitization due to dephosphorylation may be two independent events that remain linked due to absence of tools to precisely dissect these processes. Therefore, the role of receptor internalization for resensitization is an enigma that raises the question whether desensitization and internalization are independent or interdependent processes. We believe that with development of more precise tools and techniques, the link between the two processes will be resolved. Resolution of this issue will provide a better appreciation of βAR resensitization as a process that is critical for proper receptor function and manifestation of the appropriate cellular responses.

Mechanisms Underlying Resensitization of βARs

Although analysis on βAR dephosphorylation has been used as surrogate to provide an idea on the state of receptor function, little is known about the mechanisms regulating the process of receptor resensitization. An important question that is unanswered in the above studies on dephosphorylation is what determines the activity and localization of phosphatases at the plasma membrane? In this regard, studies have shown that different scaffolding A-kinase anchoring proteins (AKAPs) are involved in targeting phosphatase to the βAR complex.57 One of the AKAPs, Gravin has been shown to associate with βAR57,58 and its interaction increases with agonist stimulation recruiting PP2A to the receptor complex.58,59 Another AKAP, AKAP 79 is associated with βARs as a multi-protein complex containing protein phosphatase 2B (calcineurin) and PKA.60,61 In this context, interestingly siRNA targeting of AKAP 5 results in loss of extracellular regulated kinase ½ (ERK ½) activation and the ability of the cells to resensitize internalized desensitized βARs.62 Importantly, the series of AKAP studies establish the idea that dephosphorylation of βARs could occur due to factors present constitutively at the plasma membrane or could be recruited following agonist stimulation.56 Once these factors are present in the complex, they may accomplish the βAR dephosphorylation potentially either on the plasma membranes or in the endosomes. These studies have tried to establish the concept that dephosphorylation of βARs is a critical step in the process of regulating receptor function and deregulation in this process could affect βAR function as potently as receptor desensitization. The potent role of resensitization in βAR function is just beginning to be appreciated and studies by Tao et al.62 provides a glimpse of expanding importance of phosphatases in βAR resensitization and their role in receptor function.

Despite these interesting studies on AKAPs regulating βAR function, very little is known about indepth mechanisms regulating βAR resensitization. It is not known whether phosphatases that bring about resensitization are acutely regulated and if so, what are the underlying mechanisms. Previous studies using transgenic mice with cardiac-overexpression of inactive PI3Kγ (PI3Kγinact) showed significant preservation of βAR function despite the presence of cardiac stress.63 In contrast, βARs were significantly desensitized in the wild-type littermate controls suggesting that presence of active PI3Kγ leads to significant βAR desensitization and loss of receptor from the cardiac plasma membranes. Further studies in PI3Kγ knock out64 and knock in65 mice demonstrates the critical role of PI3Kγ in regulating βAR function. Thus, absence of PI3Kγ activity seems to preserve βAR function which is beneficial while its presence is deleterious as it drives βAR desensitization. Furthermore, βAR phosphorylation was not inhibited in the cells expressing PI3Kγinact66 or in the hearts of PI3Kγinact transgenic mice63 indicating that the critical steps in receptor phosphorylation and desensitization are intact in these settings. These studies therefore provide capabilities to distinguish between mechanisms regulating receptor desensitization vs. resensitization indicating that they are two processes that may be independent but were interlinked due to the absence of appropriate tools and technology.

The observation that presence of PI3Kγ results in βAR desensitization and absence leads to preservation of receptor function laid the foundation that PI3Kγ may inhibit βAR resensitization. Consistent with this postulation, our studies show that inhibition of PI3Kγ by pharmacologic or genetic means results in significant activation of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) activity.67 The significant increase in PP2A activity effectively dephosphorylates βARs resulting in resensitization and preservation of βAR function despite agonist. Since βAR internalization is significantly attenuated by inhibition of PI3Kγ,68 dephosphorylation of βARs observed in these conditions indicates that receptors undergo resensitization at the plasma membrane. These studies bring out an interesting concept regarding previous paradigm on resensitization wherein it is articulated that receptor endocytosis (internalization) and resensitization go hand in hand. In this context, our studies show that βAR internalization is not required for resensitization.67 Consistent with this idea, recent studies in morphine receptors (MOR) show that dephosphorylation of MOR occurs even in the absence of endocytosis in the neurons.69,70 These studies therefore seem to support some of the earliest observations with serotonin 5-HT2A receptor in the C6 glioma cells wherein receptor resensitization occurred without recycling.71 But these findings could not be replicated in human embryonic kidney 293 (HEK 293) cells indicating cell-specific regulation of receptor dephosphorylation and resensitization. Furthermore, evidence from the use of chemically synthesized βAR agonists show that certain agonists can actually dissociate phosphorylation and internalization mechanism72 supporting the observation in C6 glioma cells. Particularly, it is important to appreciate that mechanisms of resensitization may be different in cultured cells vs. the primary cells. Primary cells may have functionally evolved in a context specific manner being an integral component of an organ with divided responsibility. These observations brings to fore the idea that phosphorylation, internalization and dephosphorylation are independent events and can potentially be altered/manipulated with the use of novel tools that is becoming available to researchers.

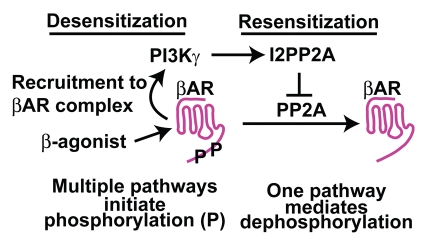

Despite the increasing appreciation that resensitization is a critical and an equal partner to desensitization in regulating βAR function little is mechanistically understood. Recently we have shown that βAR resensitization is a tightly regulated independent process that can be altered in conditions of pathology affecting βAR function and overall outcome. Our studies show that PI3Kγ inhibition preserves βAR function by allowing effective resensitization as inhibition of PP2A in these conditions leads to loss of preserved receptor function. This provides direct evidence that PP2A is a critical player in βAR resensitization consistent with previous studies in reference 45. Despite significant lower cardiac PP2A activity in conditions of cardiac stress, we observed no significant changes in the PP2A protein levels (unpublished data) suggesting alternative mechanisms of PP2A regulation. We have identified that PI3Kγ phosphorylates the endogenous inhibitor of PP2A, I2PP2A enhancing its interaction of I2PP2A to PP2A. This enhanced interaction results in inhibition of PP2A activity resulting in accumulation of phosphorylated βARs on the plasma membrane i.e., desensitized receptors (Fig. 3). This shift in balance toward phosphorylated receptor happens due to recruitment of PI3Kγ to the receptor complex following agonist stimulation63,73 as absence of active PI3Kγ leads to normalization of βAR function despite the presence of agonist (Fig. 3). This normalization is due to efficient dephosphorylation of the βARs mediated by PP2A as I2PP2A is not phosphorylated (due to absence of active PI3Kγ) and therefore cannot inhibit PP2A activity.67 These studies therefore provide clear evidence that desensitization and resensitization are independent processes and better understanding of the mechanisms will allow us to appreciate the nuances in regulation of βAR function. Consistent with the previous observations with 5-HT2A receptor,71 our studies show that in the absence of active PI3Kγ at the receptor complex, βARs can effectively undergo plasma membrane dephosphorylation and resensitization. As efforts to dissect resensitization mechanisms intensify, there will be development of novel tools that will allow for reinforcing the concept that desensitization and resensitization are not interdependent but independent processes. The functional consequences of these interesting observations in various physiological contexts remain to be explored and thus understanding these processes from that perspective allows for targeting molecules on this pathway hitherto never considered targetable.

Figure 3.

Emerging paradigm of βAR resensitization.

Functional Significance of βAR Resensitization

Recent studies provide compelling evidence that resensitization should be considered as an equal partner to desensitization in the process of regulating βAR function as deregulation of resensitization would cause as much effect on receptor function as would deregulation of desensitization. Increasing the prominence of resensitization as critical player in βAR function brings the molecules regulating receptor resensitization into the realm of therapeutic targeting. This has tremendous therapeutic implications especially with respect to heart failure, asthma and COPD (chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) as it opens up an array of new targets that would normalize receptor function and provide beneficial effects. In view of the knowledge that βARs are desensitized and uncoupled from their cognate G proteins in heart failure,3,74 the ability to normalize receptor function therefore holds a great therapeutic promise. This is an important progress that needs appreciation as current functional significance of βAR signaling is primarily based on desensitization arm of the receptor function with little or no consideration given to the resensitization. On the same note, it has to be highlighted that chronic activation of βARs is shown to enhance proliferation and metastasis of breast cancer11 indicating that instead of normalization, inhibition of receptor function by β-blocker is an appropriate mode of therapeutic intervention. Therefore, it is important that normalization of βAR function in a given pathology needs to be addressed in a context specific manner wherein resensitization as a process can be activated/inhibited to switch on/off the receptor. Although mechanistic understanding of resensitization is in its formative years, we believe that resensitization as a process ignored for this long will become central to comprehensive understanding of βAR function. Thus we believe that with time, functional alterations in βAR resensitization will be considered as an equivalent integral regulator of receptor function like desensitization.

Conclusion

The overall goal of this review is to highlight the knowledge gap with regards to understanding the contribution of resensitization in regulating βAR function and signaling. Given that βARs undergo desensitization and needs to be resensitized for the next wave of stimulation, understanding mechanisms of resensitization will have important physiological significance. We believe that in addition to the appreciated role of desensitization, resensitization may also play a critical role in cellular homeostasis by fine tuning responsiveness. Such fine tuning can be provided by differential receptor resensitization mechanisms wherein need of quicker, powerful and acute response could be executed by plasma membrane resensitization, while prolonged adaptive signaling could involve trafficking of βAR through endosomal compartments. These differential processes of resensitization may involve cell's natural response to the stimulation based on its need. This dynamic aspect of resensitization contributing to maintenance of cellular function depicts a more active role of resensitization in regulating receptor function than previously appreciated. Thus in this context, understanding the underlying mechanisms of βAR resensitization is not only important for receptor function but may provide tools for novel therapeutic strategies.

Acknowledgments

The work is supported by NIH grants HL089473, HL089473-02S1 to S.V.NP., AHA postdoctoral fellowship to N.T.V. S.V.NP. and S.K.G supported by IUSSTF joint centre.

References

- 1.Magalhaes AC, Dunn H, Ferguson SS. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor activity, trafficking and localization by Gpcr-interacting proteins. Br J Pharmacol. 2011 doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01552.x. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferguson SS. Evolving concepts in G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis: the role in receptor desensitization and signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2001;53:1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rockman HA, Koch WJ, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane-spanning receptors and heart function. Nature. 2002;415:206–212. doi: 10.1038/415206a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. β-arrestin-mediated receptor trafficking and signal transduction. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:521–533. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Claing A, Laporte SA, Caron MG, Lefkowitz RJ. Endocytosis of G protein-coupled receptors: roles of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and β-arrestin proteins. Prog Neurobiol. 2002;66:61–79. doi: 10.1016/S0301-0082(01)00023-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Luttrell LM, Gesty-Palmer D. Beyond desensitization: physiological relevance of arrestin-dependent signaling. Pharmacol Rev. 2010;62:305–330. doi: 10.1124/pr.109.002436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Daly CJ, McGrath JC. Previously unsuspected widespread cellular and tissue distribution of β-adrenoceptors and its relevance to drug action. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2011;32:219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2011.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Brodde OE. β1 and β2 adrenoceptor polymorphisms: functional importance, impact on cardiovascular diseases and drug responses. Pharmacol Ther. 2008;117:1–29. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2007.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Walker JK, Penn RB, Hanania NA, Dickey BF, Bond RA. New perspectives regarding β(2) -adrenoceptor ligands in the treatment of asthma. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:18–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01178.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shore SA, Drazen JM. B-agonists and asthma: too much of a good thing? J Clin Invest. 2003;112:495–497. doi: 10.1172/JCI19642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Schuller HM. β-adrenergic signaling, a novel target for cancer therapy? Oncotarget. 2010;1:466–469. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Powe DG, Voss MJ, Zanker KS, Habashy HO, Green AR, Ellis IO, et al. B-blocker drug therapy reduces secondary cancer formation in breast cancer and improves cancer specific survival. Oncotarget. 2010;1:628–638. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shore SA, Moore PE. Regulation of β-adrenergic responses in airway smooth muscle. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2003;137:179–195. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9048(03)00146-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Daaka Y, Luttrell LM, Lefkowitz RJ. Switching of the coupling of the β2-adrenergic receptor to different G proteins by protein kinase A. Nature. 1997;390:88–91. doi: 10.1038/36362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajagopal S, Rajagopal K, Lefkowitz RJ. Teaching old receptors new tricks: biasing seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2010;9:373–386. doi: 10.1038/nrd3024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kendall RT, Strungs EG, Rachidi SM, Lee MH, El-Shewy HM, Luttrell DK, et al. The β-arrestin pathway-selective type 1A angiotensin receptor (AT1A) agonist [Sar1, Ile4, Ile8] angiotensin II regulates a robust G protein-independent signaling network. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:19880–19891. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.233080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lefkowitz RJ, Pitcher J, Krueger K, Daaka Y. Mechanisms of β-adrenergic receptor desensitization and resensitization. Adv Pharmacol. 1998;42:416–420. doi: 10.1016/S1054-3589(08)60777-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benovic JL, Pike LJ, Cerione RA, Staniszewski C, Yoshimasa T, Codina J, et al. Phosphorylation of the mammalian β-adrenergic receptor by cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase. Regulation of the rate of receptor phosphorylation and dephosphorylation by agonist occupancy and effects on coupling of the receptor to the stimulatory guanine nucleotide regulatory protein. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:7094–7101. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dorn GW., 2nd GRK mythology: G protein receptor kinases in cardiovascular disease. J Mol Med (Berl) 2009;87:455–463. doi: 10.1007/s00109-009-0450-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lefkowitz RJ. G protein-coupled receptors. III. New roles for receptor kinases and β-arrestins in receptor signaling and desensitization. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:18677–18680. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.30.18677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Drake MT, Shenoy SK, Lefkowitz RJ. Trafficking of G protein-coupled receptors. Circ Res. 2006;99:570–582. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000242563.47507.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Prabhu SD. Cytokine-induced modulation of cardiac function. Circ Res. 2004;95:1140–1153. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000150734.79804.92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gulick T, Chung MK, Pieper SJ, Lange LG, Schreiner GF. Interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor inhibit cardiac myocyte β-adrenergic responsiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:6753–6757. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.17.6753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Santos CX, Anilkumar N, Zhang M, Brewer AC, Shah AM. Redox signaling in cardiac myocytes. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011;50:777–793. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nediani C, Raimondi L, Borchi E, Cerbai E. Nitric oxide/reactive oxygen species generation and nitroso/redox imbalance in heart failure: from molecular mechanisms to therapeutic implications. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2011;14:289–331. doi: 10.1089/ars.2010.3198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Donoso P, Sanchez G, Bull R, Hidalgo C. Modulation of cardiac ryanodine receptor activity by ROS and RNS. Front Biosci. 2011;16:553–567. doi: 10.2741/3705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gupta MK, Neelakantan TV, Sanghamitra M, Tyagi RK, Dinda A, Maulik S, et al. An assessment of the role of reactive oxygen species and redox signaling in norepinephrine-induced apoptosis and hypertrophy of H9c2 cardiac myoblasts. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2006;8:1081–1093. doi: 10.1089/ars.2006.8.1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guo J, Gertsberg Z, Ozgen N, Steinberg SF. p66Shc links alpha1-adrenergic receptors to a reactive oxygen species-dependent AKT-FOXO3A phosphorylation pathway in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2009;104:660–669. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.186288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu Q, Dalic A, Fang L, Kiriazis H, Ritchie RH, Sim K, et al. Myocardial oxidative stress contributes to transgenic β-adrenoceptor activation-induced cardiomyopathy and heart failure. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;162:1012–1028. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2010.01043.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Flohé L. Changing paradigms in thiology from anti-oxidant defense toward redox regulation. Methods Enzymol. 2010;473:1–39. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(10)73001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rudolph V, Freeman BA. Cardiovascular consequences when nitric oxide and lipid signaling converge. Circ Res. 2009;105:511–522. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.202077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whalen EJ, Foster MW, Matsumoto A, Ozawa K, Violin JD, Que LG, et al. Regulation of β-adrenergic receptor signaling by S-nitrosylation of G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2. Cell. 2007;129:511–522. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ozawa K, Whalen EJ, Nelson CD, Mu Y, Hess DT, Lefkowitz RJ, et al. S-nitrosylation of β-arrestin regulates β-adrenergic receptor trafficking. Mol Cell. 2008;31:395–405. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang G, Moniri NH, Ozawa K, Stamler JS, Daaka Y. Nitric oxide regulates endocytosis by S-nitrosylation of dynamin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:1295–1300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508354103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wachsman DE, Kavaler JP, Sugar IP, Schachter EN, Gonsiorek W, Maayani S. Kinetic studies of desensitization and resensitization of the relaxation response to β2 adrenoceptor agonists in isolated guinea pig trachea. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:332–345. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferguson SS, Caron MG. G protein-coupled receptor adaptation mechanisms. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 1998;9:119–127. doi: 10.1006/scdb.1997.0216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Merrifield CJ, Moss SE, Ballestrem C, Imhof BA, Giese G, Wunderlich I, et al. Endocytic vesicles move at the tips of actin tails in cultured mast cells. Nat Cell Biol. 1999;1:72–74. doi: 10.1038/9048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naga Prasad SV, Jayatilleke A, Madamanchi A, Rockman HA. Protein kinase activity of phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulates β-adrenergic receptor endocytosis. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:785–796. doi: 10.1038/ncb1278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Seachrist JL, Anborgh PH, Ferguson SS. β2-adrenergic receptor internalization, endosomal sorting and plasma membrane recycling are regulated by rab GTPases. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:27221–27228. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M003657200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Seachrist JL, Ferguson SS. Regulation of G protein-coupled receptor endocytosis and trafficking by Rab GTPases. Life Sci. 2003;74:225–235. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.He J, Bellini M, Inuzuka H, Xu J, Xiong Y, Yang X, et al. Proteomic analysis of β1-adrenergic receptor interactions with PDZ scaffold proteins. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:2820–2827. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509503200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Xiang Y, Devic E, Kobilka B. The PDZ binding motif of the β1 adrenergic receptor modulates receptor trafficking and signaling in cardiac myocytes. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:33783–33790. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204136200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hu LA, Tang Y, Miller WE, Cong M, Lau AG, Lefkowitz RJ, et al. β1-adrenergic receptor association with PSD-95. Inhibition of receptor internalization and facilitation of β1-adrenergic receptor interaction with N-methyl-D-aspartate receptors. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:38659–38666. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005938200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gardner LA, Naren AP, Bahouth SW. Assembly of an SAP97-AKAP79-cAMP-dependent protein kinase scaffold at the type 1 PSD-95/DLG/ZO1 motif of the human β(1)-adrenergic receptor generates a receptosome involved in receptor recycling and networking. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5085–5099. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M608871200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krueger KM, Daaka Y, Pitcher JA, Lefkowitz RJ. The role of sequestration in G protein-coupled receptor resensitization. Regulation of β2-adrenergic receptor dephosphorylation by vesicular acidification. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:5–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Barak LS, Tiberi M, Freedman NJ, Kwatra MM, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. A highly conserved tyrosine residue in G protein-coupled receptors is required for agonist-mediated β2-adrenergic receptor sequestration. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2790–2795. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sibley DR, Strasser RH, Benovic JL, Daniel K, Lefkowitz RJ. Phosphorylation/dephosphorylation of the β-adrenergic receptor regulates its functional coupling to adenylate cyclase and subcellular distribution. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1986;83:9408–9412. doi: 10.1073/pnas.83.24.9408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yu SS, Lefkowitz RJ, Hausdorff WP. β-adrenergic receptor sequestration. A potential mechanism of receptor resensitization. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:337–341. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang J, Barak LS, Winkler KE, Caron MG, Ferguson SS. A central role for β-arrestins and clathrin-coated vesicle-mediated endocytosis in β2-adrenergic receptor resensitization. Differential regulation of receptor resensitization in two distinct cell types. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27005–27014. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.43.27005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang J, Barak LS, Anborgh PH, Laporte SA, Caron MG, Ferguson SS. Cellular trafficking of G protein-coupled receptor/β-arrestin endocytic complexes. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:10999–11006. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.16.10999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pippig S, Andexinger S, Lohse MJ. Sequestration and recycling of β2-adrenergic receptors permit receptor resensitization. Mol Pharmacol. 1995;47:666–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tran TM, Friedman J, Qunaibi E, Baameur F, Moore RH, Clark RB. Characterization of agonist stimulation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase and G protein-coupled receptor kinase phosphorylation of the β2-adrenergic receptor using phosphoserine-specific antibodies. Mol Pharmacol. 2004;65:196–206. doi: 10.1124/mol.65.1.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kelly E. G protein-coupled receptor dephosphorylation at the cell surface. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:235–236. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Iyer VS, Canty JM., Jr Regional desensitization of β-adrenergic receptor signaling in swine with chronic hibernating myocardium. Circ Res. 2005;97:789–795. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000184675.80217.9e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tran TM, Friedman J, Baameur F, Knoll BJ, Moore RH, Clark RB. Characterization of β2-adrenergic receptor dephosphorylation: Comparison with the rate of resensitization. Mol Pharmacol. 2007;71:47–60. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.028456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Iyer V, Tran TM, Foster E, Dai W, Clark RB, Knoll BJ. Differential phosphorylation and dephosphorylation of β2-adrenoceptor sites Ser262 and Ser355,356. Br J Pharmacol. 2006;147:249–259. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Shih M, Lin F, Scott JD, Wang HY, Malbon CC. Dynamic complexes of β2-adrenergic receptors with protein kinases and phosphatases and the role of gravin. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:1588–1595. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.3.1588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lin F, Wang H, Malbon CC. Gravin-mediated formation of signaling complexes in β2-adrenergic receptor desensitization and resensitization. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19025–19034. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.25.19025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tao J, Wang HY, Malbon CC. Protein kinase A regulates AKAP250 (gravin) scaffold binding to the β2-adrenergic receptor. EMBO J. 2003;22:6419–6429. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fraser ID, Cong M, Kim J, Rollins EN, Daaka Y, Lefkowitz RJ, et al. Assembly of an A kinase-anchoring protein-β(2)-adrenergic receptor complex facilitates receptor phosphorylation and signaling. Curr Biol. 2000;10:409–412. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00419-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Cong M, Perry SJ, Lin FT, Fraser ID, Hu LA, Chen W, et al. Regulation of membrane targeting of the G protein-coupled receptor kinase 2 by protein kinase A and its anchoring protein AKAP79. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:15192–15199. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M009130200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tao J, Malbon CC. G protein-coupled receptor-associated A-kinase anchoring proteins AKAP5 and AKAP12: differential signaling to MAPK and GPCR recycling. J Mol Signal. 2008;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1750-2187-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Nienaber JJ, Tachibana H, Naga Prasad SV, Esposito G, Wu D, Mao L, et al. Inhibition of receptor-localized PI3K preserves cardiac β-adrenergic receptor function and ameliorates pressure overload heart failure. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1067–1079. doi: 10.1172/JCI18213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Oudit GY, Crackower MA, Eriksson U, Sarao R, Kozieradzki I, Sasaki T, et al. Phosphoinositide-3-kinase gamma-deficient mice are protected from isoproterenol-induced heart failure. Circulation. 2003;108:2147–2152. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000091403.62293.2B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Patrucco E, Notte A, Barberis L, Selvetella G, Maffei A, Brancaccio M, et al. PI3Kgamma modulates the cardiac response to chronic pressure overload by distinct kinase-dependent and -independent effects. Cell. 2004;118:375–387. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Naga Prasad SV, Barak LS, Rapacciuolo A, Caron MG, Rockman HA. Agonist-dependent recruitment of phosphoinositide-3-kinase to the membrane by β-adrenergic receptor kinase 1. A role in receptor sequestration. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:18953–18959. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102376200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Vasudevan NT, Mohan ML, Gupta MK, Hussain AK, Naga Prasad SV. Inhibition of protein phosphatase 2A activity by PI3Kgamma regulates β-adrenergic receptor function. Mol Cell. 2011;41:636–648. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.02.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Naga Prasad SV, Laporte SA, Chamberlain D, Caron MG, Barak L, Rockman HA. Phosphoinositide-3-kinase regulates β2-adrenergic receptor endocytosis by AP-2 recruitment to the receptor/β-arrestin complex. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:563–575. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Arttamangkul S, Torrecilla M, Kobayashi K, Okano H, Williams JT. Separation of mu-opioid receptor desensitization and internalization: endogenous receptors in primary neuronal cultures. J Neurosci. 2006;26:4118–4125. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0303-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Dang VC, Chieng B, Azriel Y, Christie MJ. Cellular morphine tolerance produced by βarrestin-2-dependent impairment of mu-opioid receptor resensitization. J Neurosci. 2011;31:7122–7130. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5999-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Gray JA, Sheffler DJ, Bhatnagar A, Woods JA, Hufeisen SJ, Benovic JL, et al. Cell-type specific effects of endocytosis inhibitors on 5-hydroxytryptamine(2A) receptor desensitization and resensitization reveal an arrestin-, GRK2- and GRK5-independent mode of regulation in human embryonic kidney 293 cells. Mol Pharmacol. 2001;60:1020–1030. doi: 10.1124/mol.60.5.1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moore RH, Millman EE, Godines V, Hanania NA, Tran TM, Peng H, et al. Salmeterol stimulation dissociates β2-adrenergic receptor phosphorylation and internalization. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2007;36:254–261. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0158OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Naga Prasad SV, Esposito G, Mao L, Koch WJ, Rockman HA. Gβgamma-dependent phosphoinositide-3-kinase activation in hearts with in vivo pressure overload hypertrophy. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:4693–4698. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.7.4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bristow MR. Why does the myocardium fail? Insights from basic science. Lancet. 1998;352:8–14. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(98)90311-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]