Abstract

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) fulfills criteria for a complex genetic disease in which environmental factors interact with multiple polymorphic genes to influence susceptibility. Finding the genes that influence susceptibility can be approached in hypothesis testing or unbiased study designs. In candidate gene association studies, genetic variation in, and/or levels of, expression of genes known or suspected to be involved in the pathogenesis of COPD are compared in affected and unaffected individuals. Although this approach is useful it is limited by our present knowledge of disease pathophysiology. Genomewide studies of gene expression and of genetic variation are now possible and are not constrained by our limited knowledge. Although both of these unbiased approaches are in their infancy, they have already provided exciting new avenues for future investigation and potentially now approaches to risk prediction and therapy.

Keywords: chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, genetics, genomics

At this symposium, three talks were given related to the genetics and genomics of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Peter Paré concentrated on candidate gene studies in which biologically plausible genes have been tested for variants that may impart increased risk for a rapid decline of lung function among smokers. Edwin Silverman focused on the promising approach offered by genome-wide association (GWA) studies, and Avrum Spira reviewed the state of the art with respect to the examination of gene expression at the mRNA level and its relationship to COPD phenotype.

CANDIDATE GENE STUDIES

In candidate gene association studies, genetic variants in genes thought to be involved in pathobiological pathways leading to COPD are tested for statistical association with one or more COPD phenotype. Sandford and his colleagues have taken advantage of the well-characterized Lung Health Study cohort study to examine gene variants associated with rapid decline in lung function (1). They selected the phenotypic extremes from among the approximately 6,000 individuals in that study; the approximately 300 continued smokers who had the most rapid and the approximately 300 who had the least rapid decline in FEV1 over the first 5 years of the study. To date they have examined over 50 genes, and Table 1 shows a summary of those in which they have found polymorphisms that impart increased or decreased risk for rapid decline. Also shown is the frequency of the risk or protective allele and the odds ratio associated with that allele. Finally, the attributable risk for the specific alleles associated with increased risk is shown. The attributable risk estimates the contribution of that polymorphism to the overall risk of being in the fast or slow decline group in this “population.” The association of a number of these genes with rate of decline of lung function has been replicated in independent populations (2–7).

TABLE 1.

SIGNIFICANT GENETIC ASSOCIATIONS WITH RAPID DECLINE IN LUNG FUNCTION IN THE LUNG HEALTH STUDY

| Candidate Gene | Odds Ratio | Relative Frequencies | Attributable Risk (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| a1-AT Z | 2.8 (1.2, 7.3) | 6% vs. 3% | 5 |

| mEH Tyr113 > His, Arg139 > His * | 2.4 (1.1–5.4) | 7% vs. 3% | 4 |

| β2AR Glu27 > Gln | 0.6 (0.4–0.8) | 44% vs. 57% | |

| Haplotype IL1RN A1/IL1B –511T | 1.4 (1–(2.1) | 14% vs. 10% | 4 |

| Haplotype IL1RN A2/IL1B –511C | 1.5 (1.1–2.1) | 20% vs. 14% | 7 |

| IL1RN | 1.6 (1.1–2.3) | 72% vs. 62% | 3 |

| IL8 A-251T | 1.32 | 58% vs. 51% | 5 |

| IL6 | 1.9 (1.1–3.2) | 24% vs. 14% | 11 |

| MMP-1 -1607+G | 1.6 (1.1–2.4) | 28% vs. 19% | 10 |

| IL4RA | 2.2 | 7% vs. 4% | 5 |

| Glutathione Transferases* (GSTP1 Ile105 > Val, GSTT1& GSTM1) | 2.8 (1.1–7.2) | 5% vs. 2% | 3 |

| Heme oxygenase-1 | 1.6 (1.0–2.3) | 25% vs. 18% | 10 |

| Catalase | 1.5 (1.1–2.2) | 30% vs. 22% | 10 |

| Nicotine Receptor (CHRNA5) | 3.0 (1.2–7.6) | 41% vs. 36% | 4 |

The candidate genes are: a1-ATZ = heterozygosity for the Z allele of alpha one antitrypsin; mEH = microsomal epoxide hydrolase; β2AR = the beta 2 adrenergic receptor; IL1RN A = the interleukin 1 receptor antagonist; IL8 = interleukin 8; IL6 = interleukin 6; MMP-1 = the matrix metalloproteinase 1; IL4R = the interleukin 4 receptor; glutathione transferases (GSTP1, GSTT1 and GSTM1); heme oxygenase-1; catalase; and the nicotine receptor (CHRNA5).

Other investigators have studied the same or additional genes in different cohorts of smokers for whom longitudinal lung function data are available. These studies confirmed the contributions of variants in microsomal epoxide hydrolase, heme oxygenase-1, and the glutathione S-transferases and have also implicated ADAM 33, cytochrome P450, and glutamate cystein ligase (2–7).

For microsomal epoxide hydrolase and the glutathione transferases the odds ratios, frequencies, and attributable risk pertain to the presence of a compound genotype consisting of the presence of 2 (mEH) or 3 (glutathiones) risk alleles.

Although such candidate gene studies are useful, they are limited by their very nature to the study of genes that are known to have some function that could contribute to the development of, or protection from, COPD. It is highly likely that many genes with unknown function contribute to pathogenesis, but until recently it has not been practical to interrogate the entire genome either at the DNA or RNA level. Recent advances in genome-wide genotyping and transcriptomic analysis make such an unbiased approach possible.

GENOME-WIDE ASSOCIATION STUDIES

Technical improvements in SNP genotyping within the past 5 years have led to markedly increased genotyping capacity at reduced cost. Combined with the identification of millions of common SNPs through the HapMap project, high-throughput genotyping approaches have made GWA studies a feasible study design in complex disease genetics. Rather than beginning with family-based linkage studies or candidate gene studies to limit the genomic regions of interest, GWA studies include a panel of hundreds of thousands of SNPs across the entire genome (8). Although there are approximately 10 million common SNPs in the human genome, approximately 500,000 well-selected SNPs can adequately capture the information of most SNPs in white and Asian populations (9). Because hundreds of thousands of statistical tests of genetic association are performed, stringent thresholds to establish statistical significance are required in GWA studies. Nonetheless, GWA studies have unequivocally identified genome-wide significant associations in a rapidly growing number of complex diseases, including age-related macular degeneration, diabetes mellitus, Crohn's disease, and asthma (10).

In a recent collaborative GWA study led by Drs. Sreekumar Pillai and David Goldstein (11), 823 subjects with COPD and 810 smoking control subjects from Norway underwent genome-wide SNP genotyping with the Illumina HumanHap550 SNP panel. Association analysis for COPD affection status was performed using logistic regression analysis with covariates including age, sex, current smoking status, and pack-years of smoking. After GWA analysis was performed, the top 100 SNPs were genotyped in 1,891 individuals from 606 pedigrees in the International COPD Genetics Network (ICGN). Family-based association analysis for COPD was performed using the same covariates as in the Norway population, and seven SNPs with significant P values in both populations were tested for further replication in 389 subjects with COPD from the National Emphysema Treatment Trial (NETT) and 472 smoking control subjects from the Normative Aging Study (NAS). Combined P values from all three study populations were calculated. A SNP on chromosome 15 (rs8034191) was identified with genome-wide significant association to COPD (P = 2 × 10−10), with the same direction of association (i.e., the same risk allele) in all three populations. There are multiple genes of interest near the most highly associated SNP, including several subunits of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (CHRNA3 and CHRNA5) and an iron-binding protein (IREB2). Because of the extensive linkage disequilibrium in this region, it is not possible to identify one key candidate gene; intensive study of all of the genes from this region will be required to identify all common variants and to determine if rare variants also contribute to COPD susceptibility. Of interest, this locus was also recently associated with lung cancer susceptibility in three independent reports (12–14), with peripheral vascular disease, and with nicotine addiction (15) (Table 2), suggesting that this locus may be associated with both COPD and lung cancer by influencing smoking behavior. A study from New Zealand has demonstrated associations of this genomic region with both COPD and lung cancer (16), raising the possibility that the lung cancer associations could be confounded by the frequent co-occurrence of COPD and lung cancer.

TABLE 2.

GENOME-WIDE ASSOCIATION STUDIES WITH SIGNIFICANT ASSOCIATIONS IN THE CHROMOSOME 15 CHRNA3/5 REGION

| Reference | Phenotype | Study Population | SNP with Most Significant Association | Evidence for Association |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pillai (2009) (11) | COPD | Norway: 823 cases and 810 controls | rs8034191 | P = 0.0001 |

| Pillai (2009) (11) | COPD | ICGN: 1,891 siblings in 606 families | rs1051730 | P = 7 × 1 0−6 |

| Pillai (2009) (11) | COPD | NETT-NAS: 389 cases and 472 controls | rs8034191 | P = 0.003 |

| Amos (2008) (12) | Lung cancer | Total of 3,878 cases and 4,831 controls | rs8034191 | Combined P = 3 × 1 0−18 |

| Hung (2008) (13) | Lung cancer | Total of 4,435 cases and 7,272 controls | rs8034191 | Combined P = 5 × 1 0−20 |

| Thorgeirsson (2008) (14) | Lung cancer | Total of 1,024 cases and 32,244 controls | rs1051730 | Combined P = 2 × 1 0−8 |

| Thorgeirsson (2008) (14) | Peripheral arterial disease | Total of 2,738 cases and 29,964 controls | rs1051730 | Combined P = 1 × 1 0−7 |

| Thorgeirsson (2008) (14) | Nicotine addiction (cigarettes per day as a categorical variable) | 15,771 subjects | rs1051730 | Combined P = 6 × 1 0−20 |

| Berrettini (2008) (17) | Nicotine addiction (cigarettes per day) | 5,634 Lausanne residents 1,847 subjects selected based on cholesterol and triglyceride levels | rs6495308 | P = 0.0006 P = 0.009 |

Definition of abbreviations: COPD = chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; ICGN = International COPD Genetics Network; NETT-NAS = National Emphysema Treatment Trial–Normative Aging Study; SNP = single nucleotide polymorphism.

The second GWA study of a COPD-related phenotype was performed in 7,691 participants in the Framingham Heart Study (17). FEV1/FVC was the primary phenotype analyzed. Four SNPs on chromosome 4q were strongly associated with FEV1/FVC in Framingham, and one of these SNPs was also associated with FEV1/FVC in the Family Heart Study. Of interest, SNPs in this same region also showed evidence for association with COPD in the Norway case-control study, ICGN, and NETT-NAS studies (11). Although FEV1/FVC was the primary phenotype analyzed in the Framingham Heart Study and Family Heart Study, significant evidence for association to COPD affection status was also observed in the Family Heart Study. The most strongly associated SNP is near the gene that codes for the hedgehog interacting protein (HHIP), but the functional variant or variants in this region have not been identified. Significant associations to the CHRNA3/5 region were not observed in the Framingham population.

Although GWA studies in COPD are in their infancy, the chromosome 4 and 15 genetic associations are the most statistically compelling associations reported to date. Additional GWA studies of COPD and COPD-related phenotypes may provide novel insights into COPD pathophysiology.

GENE EXPRESSION STUDIES

Whole-genome gene expression studies of diseased lung and airway tissue provide an opportunity to gain an unbiased portrait of the COPD molecular landscape, offering insights into the processes that contribute to disease pathogenesis. While this rich molecular understanding of COPD could ultimately enable development of novel therapeutic approaches to target these pathogenic processes, we remain at the beginning of this journey. There are presently very few whole-genome expression studies of COPD lung tissue in humans (18–22). Some of the initial enthusiasm for using genome-wide gene expression in the setting of COPD has been diminished by the apparent lack of overlap, among these early studies, for genes differentially expressed in COPD lung tissue (21).

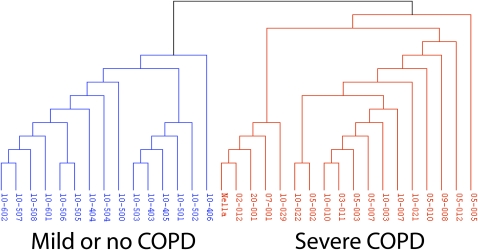

Two recent studies have shed some much-needed light on the potential relationships between existing gene expression studies of COPD lung tissue. They have attempted to overcome the inherent challenges in integrating results from relatively small studies that differ in inclusion/exclusion criteria, expression platform, and approaches for data analysis. Zeskind and coworkers (23) found that there was a high degree of overlap in the biological themes represented by the genes identified in the individual studies. While the differentially expressed genes are largely nonoverlapping, this study was able to use Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) (24) to demonstrate that the gene-expression results from each paper share fundamental similarities. In a recently published study, Bhattacharya and colleagues (22) identified 220 genes whose expression in lung tissue was associated with COPD-related phenotypes in a cohort of 56 subjects with and without COPD. Importantly, they showed that a subset of these transcripts could serve as a biomarker distinguishing lung tissue from smokers with severe COPD versus mild or no COPD in a previously published gene-expression dataset (18) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Hierarchical clustering of the lung tissue samples from the Spira and coworkers (18) study according to the expression of an 84 probeset biomarker derived from the study of Bhattacharya and colleagues (22). Dendogram of the samples from the study by Spira and coworkers is shown. The biomarker genes derived from the Bhattacharya study are able to accurately distinguish severe chronic obstructive pulmonary disease versus normal lung tissue in that independent cohort. Reproduced by permission from Reference 22.

One exciting development has been the study of airway epithelial gene expression profiles in smokers with and without COPD. This work has been motivated by the concept that smoking creates a “field of molecular injury” in epithelial cells lining the entire respiratory tract, and that airway epithelial gene expression reflects host response to, and damage from, cigarette smoke (25–27). Heterogeneity in this expression pattern has been associated with tobacco-associated lung cancer (28, 29) and may provide insights into COPD-related processes. Pierrou and coworkers (30, 13) identified 200 oxidative stress-related genes that were differentially expressed in the bronchial airways between smokers with and without COPD. More recently, Tilley and colleagues (31) demonstrated that several Notch ligands, receptors, and downstream effector genes are down-regulated in the small airways (10th–12th generation) of smokers with COPD. Interestingly, Pierrou and coworkers found that a sizable fraction of the genes with COPD-specific patterns of differential expression in the airway were also differentially expressed in a previously published COPD lung tissue dataset (18). The ability to identify COPD-related processes in airway gene expression raises the possibility of developing airway biomarkers that could be used clinically to identify smokers at higher risk for developing disease as well as to serve as intermediate biomarkers of efficacy for novel and existing COPD therapies.

While there have been relatively few whole-genome expression studies of lung tissue and airways in COPD, some common themes are emerging across datasets to offer insights into disease pathogenesis. Larger studies on well-characterized cohorts of smokers with and without COPD using newer generations of microarrays and sequencing technology are needed to overcome many of the limitations of these early studies. Integration of these transcriptomic studies with whole-genome microRNA, methylation, and genotyping studies will ultimately yield a comprehensive molecular atlas of COPD.

Supported by NIH grant HL086936 (Characterization of COPD and Modulation of Disease Progression, to Jeanine D'Armiento)

Conflict of Interest Statement: E.K.S. served as a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline (GSK) and AstraZeneca (AZ) $10,001–$50,000. He has received lecture fees from GSK $1,001–$5,000 and AZ $5,001–$10,000 and has received grant support from GSK, the NIH $100,001–more, and the American Lung Association $10,001–$50,000. A.S. served as a consultant for AllegroDx Inc. $10,001–$50,000 and also served on their Board or Advisory Board. He owns stocks or options of AllegroDx Inc. and has received grant support from the NIH $100,001–more. P.D.P. served on the Advisory Board for Talecris Biotherapeutics and received grant support from GSK, Merck, $100,001 or more, the NIH $50,001–$100,000, CIHR (Canada), and AllerGen NCE $100,001 or more.

References

- 1.Sandford AJ, Chagani T, Weir TD, Connett JE, Anthonisen NR, Paré PD. Susceptibility genes for rapid decline of lung function in the lung health study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2001;163:469–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cheng SL, Yu CJ, Chen CJ, Yang PC. Genetic polymorphism of epoxide hydrolase and glutathione S-transferase in COPD. Eur Respir J 2004;23:818–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Diemen CC, Postma DS, Vonk JM, Bruinenberg M, Schouten JP, Boezen HM. A disintegrin and metalloprotease 33 polymorphisms and lung function decline in the general population. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2005;172:329–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aubier M, Guenegou A, Benessiano J, Leynaert B, Boczkowski J, Neukirch F. Association of lung function decline with the microsatellite polymorphism in the heme oxygenase-1 gene promoter, in a general population sample. Results from the Longitudinal European Community Respiratory Health Survey (ECRHS-France). Bull Acad Natl Méd 2006;190:877–890. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Imboden M, Downs SH, Senn O, Matyas G, Brändli O, Russi EW, Schindler C, Ackermann-Liebrich U, Berger W, Probst-Hensch NM. SAPALDIA Team. Glutathione S-transferase genotypes modify lung function decline in the general population: SAPALDIA cohort study. Respir Res 2007;8:2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Seo T, Pahwa P, McDuffie HH, Yurube K, Egoshi M, Umemoto Y, Ghosh S, Fukushima Y, Nakagawa K. Association between cytochrome P450 3A5 polymorphism and the lung function in Saskatchewan grain workers. Pharmacogenet Genomics 2008;18:487–493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Siedlinski M, Postma DS, van Diemen CC, Blokstra A, Smit HA, Boezen HM. Lung function loss, smoking, vitamin C intake, and polymorphisms of the glutamate-cysteine ligase genes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;178:13–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hirschhorn JN, Daly MJ. Genome-wide association studies for common diseases and complex traits. Nat Rev Genet 2005;6:95–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eberle MA, Ng PC, Kuhn K, Zhou L, Peiffer DA, Galver L, Viaud-Martinez KA, Lawley CT, Gunderson KL, Shen R, et al. Power to detect risk alleles using genome-wide tag SNP panels. PLoS Genet 2007;3:1827–1837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Manolio TA, Brooks LD, Collins FSA. HapMap harvest of insights into the genetics of common disease. J Clin Invest 2008;118:1590–1605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pillai SG, Ge D, Zhu G, Kong X, Shianna KV, Need AC, Feng S, Hersh CP, Bakke P, Gulsvik A,et al. A genome-wide association study in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD): identification of two major susceptibility loci. PLoS Genet 2009;5(3):e1000421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Amos CI, Wu X, Broderick P, Gorlov IP, Gu J, Eisen T, Dong Q, Zhang Q, Gu X, Vijayakrishnan J, et al. Genome-wide association scan of tag SNPs identifies a susceptibility locus for lung cancer at 15q25.1. Nat Genet 2008;40:616–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hung RJ, McKay JD, Gaborieau V, Boffetta P, Hashibe M, Zaridze D, Mukeria A, Szeszenia-Dabrowska N, Lissowska J, Rudnai P, et al. A susceptibility locus for lung cancer maps to nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit genes on 15q25. Nature 2008;452:633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thorgeirsson TE, Geller F, Sulem P, Rafnar T, Wiste A, Magnusson KP, Manolescu A, Thorleifsson G, Stefansson H, Ingason A, et al. A variant associated with nicotine dependence, lung cancer and peripheral arterial disease. Nature 2008;452:638–642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Berrettini W, Yuan X, Tozzi F, Song K, Francks C, Chilcoat H, Waterworth D, Muglia P, Mooser V. Alpha-5/alpha-3 nicotinic receptor subunit alleles increase risk for heavy smoking. Mol Psychiatry 2008;13:368–373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Young RP, Hopkins RJ, Hay BA, Epton MJ, Black PN, Gamble GD. Lung cancer gene associated with COPD: triple whammy or possible confounding effect? Eur Respir J 2008;32:1158–1164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wilk JB, Chen T-H, Gottlieb DJ, Walter RE, Nagle MW, Brandler BJ, Myers RH, Borecki IB, Silverman EK, Weiss ST, et al. A genome-wide association study of pulmonary function measurements in the Framingham Heart Study. PLoS Genet 2009; (In Press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Spira A, Beane J, Pinto-Plata V, Kadar A, Liu G, Shah V, Celli B, Brody JS. Gene expression profiling of human lung tissue from smokers with severe emphysema. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:601–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Golpon HA, Coldren CD, Zamora MR, Cosgrove GP, Moore MD, Tuder RM, Geraci MW, Voelkel NF. Emphysema lung tissue gene expression profiling. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2004;31:595–600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ning W, Li CJ, Kaminski N, Feghali-Bostwick CA, Alber SM, Di YP, Otterbein SL, Song R, Hayashi S, Zhou Z, et al. Comprehensive gene expression profiles reveal pathways related to the pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:14895–14900. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang IM, Stepaniants S, Boie Y, Mortimer JR, Kennedy B, Elliott M, Hayashi S, Loy L, Coulter S, Cervino S, et al. Gene expression profiling in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and lung cancer. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2008;177:402–411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhattacharya S, Srisuma S, Demeo DL, Shapiro SD, Bueno R, Silverman EK, Reilly JJ, Mariani TJ. Molecular biomarkers for quantitative and discrete COPD phenotypes. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2009;40:359–367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zeskind JE, Lenburg ME, Spira A. Translating the COPD transcriptome: insights into pathogenesis and tools for clinical management. Proc Am Thorac Soc 2008;5:834–841. (Review). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subramanian A, Tamayo P, Mootha VK, Mukherjee S, Ebert BL, Gillette MA, Paulovich A, Pomeroy SL, Golub TR, Lander ES, et al. Gene set enrichment analysis: a knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2005;102:15545–15550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spira A, Beane J, Shah V, Liu G, Schembri F, Yang X, Palma J, Brody JS. Effects of cigarette smoke on the human airway epithelial cell transcriptome. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2004;101:10143–10148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chari R, Lonergan KM, Ng RT, MacAulay C, Lam WL, Lam S. Effect of active smoking on the human bronchial epithelium transcriptome. BMC Genomics 2007;8:297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hackett NR, Heguy A, Harvey BG, O'Connor TP, Luettich K, Flieder DB, Kaplan R, Crystal RG. Variability of antioxidant-related gene expression in the airway epithelium of cigarette smokers. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 2003;29:331–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spira A, Beane JE, Shah V, Steiling K, Liu G, Schembri F, Gilman S, Dumas YM, Calner P, Sebastiani P, et al. Airway epithelial gene expression in the diagnostic evaluation of smokers with suspect lung cancer. Nat Med 2007;13:361–366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Beane J, Sebastiani P, Whitfield TH, Steiling K, Dumas YM, Lenburg ME, Spira A. A prediction model for lung cancer diagnosis that integrates genomic and clinical features. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2008;1:56–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pierrou S, Broberg P, O'Donnell RA, Pawlowski K, Virtala R, Lindqvist E, Richter A, Wilson SJ, Angco G, Moller S, et al. Expression of genes involved in oxidative stress responses in airway epithelial cells of smokers with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:577–586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tilley AE, Harvey BG, Heguy A, Hackett NR, Wang R, O'Connor TP, Crystal RG. Down-regulation of the notch pathway in human airway epithelium in association with smoking and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2009;179:457–466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]