Abstract

Planar cell polarity (PCP) describes the orientation of a cell within the plane of an epithelial cell layer. During tissue development, epithelial cells normally align their PCP so that they face in the same direction. This alignment allows cells to move in a common direction, or to generate structures with a common orientation. A classic system for studying the coordination of epithelial PCP is the developing Drosophila wing. The alignment of epithelial PCP during pupal wing development allows the production of an array of cell hairs that point towards the wing tip. Multiple studies have established that the Frizzled (Fz) PCP signaling pathway coordinates wing PCP. Recently, we have found that the same pathway also controls the formation of ridges on the Drosophila wing membrane. However, in contrast to hair polarity, ridge orientation differs between the anterior and posterior wing. How can the Fz PCP pathway generate a different relationship between hair and ridge orientation in different parts of the wing? In this Extra View article, we discuss membrane ridge development drawing upon our recent PLoS Genetics paper and other, published and unpublished, data. We also speculate upon how our findings impact the ongoing debate concerning the interaction of the Fz PCP and Fat/Dachsous pathways in the control of PCP.

Keywords: Drosophila, frizzled, prickle, Dachsous, wing, membrane

Planar Cell Polarity and the Drosophila Wing

Planar cell polarity (PCP) describes the orientation of a cell within the plane of an epithelial cell layer. The first genetic study of PCP was undertaken by David Gubb and focused primarily upon the control of Drosophila wing hair polarity.1 The Drosophila wing has remained a primary experimental system for PCP ever since. Gubb's work identified several genes, including frizzled (fz), that are required for normal wing hair polarity and which are now acknowledged to be components of a Frizzled (Fz) PCP signaling pathway.2 Later studies established that the protocadherins Fat (Ft) and Dachsous (Ds) are components of a second signaling pathway that is also required for normal wing PCP.3 However, whether the Fz PCP and Fat/Dachsous (Ft/Ds) pathways function sequentially in a single linear PCP pathway or independently in two parallel PCP pathways remains subject to debate.4

The Fz PCP and Ft/Ds pathways also regulate PCP in vertebrates, suggesting that the elucidation of PCP mechanisms in Drosophila will be vital for our understanding of vertebrate development. The control of vertebrate PCP is critical for normal tissue morphogenesis (for example, convergent extension movements during embryogenesis) as well as for the precise alignment of epithelial structures (such as the stereocilia of the inner ear).5 Loss of normal PCP in humans has been implicated in a number of disorders, including spina bifida and polycystic kidney disease, and it is likely that further disease associations will be revealed as new roles for vertebrate PCP signaling are discovered.

Our lab has recently shown that, in addition to controlling Drosophila wing hair polarity, the Fz and Ft/Ds PCP pathways also control the orientation of ridges on the wing membrane.6,7 However, unlike wing hairs, membrane ridges have different orientations in different parts of the wing. These findings suggest that PCP signaling in the Drosophila wing is more complex than previously thought. In this Extra View article, we discuss the development of membrane ridges and their possible function. We also discuss the role of Fz PCP and Ft/Ds pathways in ridge formation and orientation, and the implications for our understanding of the relationship between the Fz PCP and Ft/Ds pathways.

Wing Membrane Structure and Function

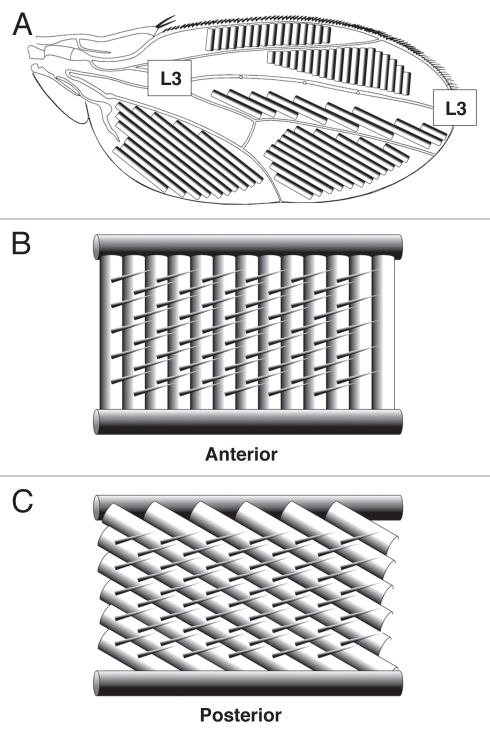

The Drosophila wing consists of a thin, transparent membrane supported by a network of veins. The wing membrane is decorated with hairs, each the product of a single epithelial cell, that point towards the distal wing tip. The membrane itself is shaped into ridges which have different orientations in different regions of the wing.6 Ridges anterior to the third longitudinal (L3) vein are aligned with the antero-posterior (A-P) axis, whereas ridges posterior to the L3 vein are aligned with the proximo-distal (P-D) axis (Fig. 1A). The specific arrangement of wing veins and the structure of the wing membrane are believed to provide the appropriate rigidity and flexibility required for insect flight.8 In the anterior Drosophila wing, membrane ridges are approximately orthogonal to longitudinal veins suggesting a rigid ‘washboard’ structure (Fig. 1B). In the posterior wing, ridges are more closely aligned with longitudinal veins suggesting a more flexible ‘concertina’ structure (Fig. 1C). This organization appears appropriate for dipteran wings, which typically have a rigid leading (anterior) edge and a flexible trailing (posterior) edge.9

Figure 1.

Organization of Drosophila wing membrane ridges. All diagrams depict the dorsal wing surface with anterior uppermost and distal to the right. (A) Schematic showing the orientation of wing membrane ridges (the width of ridges is greatly exaggerated for clarity). Proximal and distal regions of the L3 vein are labeled. Ridges anterior to the L3 vein are aligned with the antero-posterior (A-P) axis and ridges posterior to the L3 vein are aligned with the proximo-distal (P-D) axis. (B) Schematic showing the relative orientation of membrane ridges and longitudinal veins in the anterior wing. Anterior ridges are approximately orthogonal to local wing veins suggesting a rigid ‘washboard’ structure. (C) Schematic showing the relative orientation of membrane ridges and longitudinal veins in the posterior wing. Posterior ridges have a similar orientation to local wing veins suggesting a flexible ‘concertina’ structure.

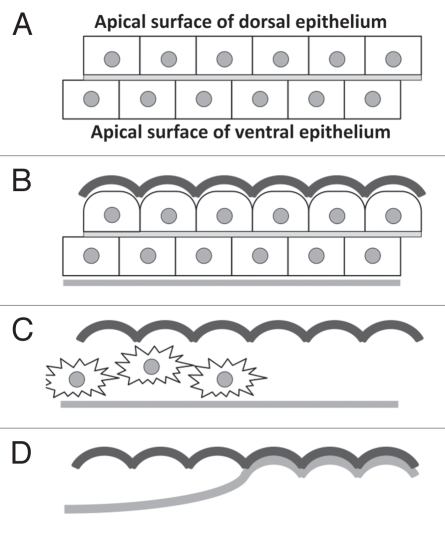

The structure of the Drosophila wing membrane raises questions about its development. The membrane is formed from cuticle secreted from the apical surface of wing epithelial cells during pupal development. However, at the time of cuticle secretion, the wing epithelium is folded to form a bilayer with dorsal and ventral cell layers (Fig. 2A). Both dorsal and ventral cells contribute cuticle to the membrane, raising the question of how these independent contributions are combined to produce a membrane with a specific, reproducible shape. A second problem arises from our finding that membrane ridge orientation is controlled by the Frizzled (Fz) Planar Cell Polarity (PCP) signaling pathway.6 The Fz PCP pathway also controls the polarity of wing hairs, which point towards the distal wing tip. How can a single signaling pathway specify different ridge orientations in the anterior and posterior wing, but the same hair polarity in both parts of the wing? Below we attempt to answers these questions by integrating findings described in our recent PLoS Genetics paper,7 along with published and unpublished data from our, and other, labs.

Figure 2.

A Master-Slave model for membrane ridge formation. All diagrams represent a cross-section of a developing Drosophila wing with the dorsal surface uppermost. (A) Dorsal and ventral wing epithelia are tightly opposed prior to cuticle secretion. Note that dorsal and ventral cell boundaries are not aligned. (B) The apical surface of dorsal wing cells changes shape before secreting an inflexible ridged cuticle (black). Ventral cells secrete a flexible cuticle (grey). (C) Shortly after the adult fly leaves the pupal case, dorsal and ventral epithelial cells delaminate and move out of the wing. (D) Dorsal and ventral wing cuticle combine. The flexible ventral cuticle molds to the shape of the ridged dorsal cuticle.

Formation of Wing Membrane Ridges

The developing pupal wing is an epithelial bilayer consisting of dorsal and ventral cell layers (Fig. 2A). Both dorsal and ventral wing cells secrete cuticle from their apical surfaces, before being lost from the wing during maturation.10 Remarkably, dorsal and ventral cuticle then combine to form a membrane with a specific, reproducible shape. How is this achieved?

A first clue came from our finding that wing hairs, which mark the apical center of wing epithelial cells, are consistently located at the top of membrane ridges on the dorsal wing surface (Doyle et al. in preparation). In contrast, ventral hair position is not coordinated with ridge shape. The fact that ridges are aligned with dorsal, but not ventral, cells suggests that the dorsal epithelium controls ridge development. Indeed, we have found that altering Fz PCP signaling in the dorsal wing epithelium alone is sufficient to alter ridge orientation on both the dorsal and ventral membrane (Doyle et al. in preparation).

Based on these findings, we propose a Master-Slave model for the formation wing membrane ridges (Fig. 2). In the model, ridged cuticle generated by the dorsal epithelium acts as a template to mold a flexible ventral cuticle into ridges. The formation of a ridged dorsal cuticle is likely to be a consequence of a change in the apical surface morphology of dorsal epithelial cells prior to cuticle secretion (Fig. 2B). This appears to be the mechanism by which epithelial cells in the developing butterfly wing generate the elaborately shaped scales that adorn the butterfly wing membrane.11 Shortly after the adult fly leaves the pupal case, dorsal and ventral epithelial cells delaminate and move out of the wing into the thorax (Fig. 2C).10 The dorsal and ventral cuticle then combine to form the mature membrane with the dorsal cuticle acting as a mold to shape the ventral cuticle (Fig. 2D).

We find that hair position is also coordinated with membrane ridges on the dorsal, but not ventral, surface of Hymenopteran wings (Doyle et al. in preparation). Since Hymenoptera are believed to be basal in the insect radiation,12 this suggests that the control of membrane shape by dorsal cells is an ancestral feature of insect wing development. This, in turn, suggests that our Master-Slave model of membrane development may apply more widely within the insect order. In support of our model, a recent study reports that the dorsal wing cuticle of the Hymenopteran Omphale is thicker than the ventral cuticle, and is the primary determinant of wing color patterns that derive from membrane structure.13

Control of Membrane Ridge Orientation

For the reasons discussed above, we believe that the dorsal wing epithelium organizes wing membrane ridges. However, this still leaves the question of how ridges are organized in different orientations in the anterior and posterior wing. Since ridge organization requires Fz PCP signaling,6 it would appear that Fz PCP signaling is in different directions in the anterior and posterior wing. However, Fz PCP signaling also organizes wing hairs, which have the same orientation in all parts of the wing suggesting that Fz PCP signaling has the same direction in the anterior and posterior wing. To resolve this apparent contradiction, we have proposed a Bidirectional-Biphasic (Bid-Bip) model of Fz PCP signaling in the wing.6,7 The model builds upon David Strutt's finding that there are early and late Fz PCP signaling events during pupal wing development.14 The Bid-Bip model elaborates on Strutt's proposal by defining the direction of the early and late Fz PCP signals, and the wing features that are organized by each signal.

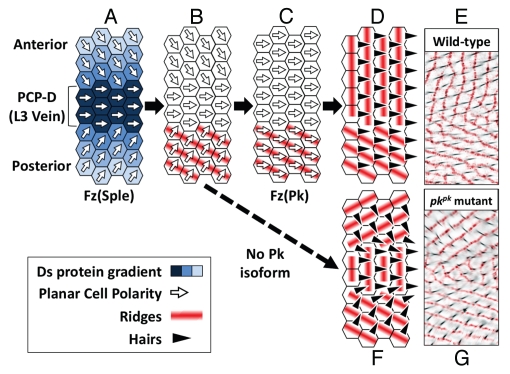

By studying wings that lack longitudinal wing veins, we found that the transition in ridge orientation between the anterior and posterior wing occurs over just a few cell diameters that span the normal site of the L3 vein. This implies an abrupt change in PCP at the site of the L3 vein and so we have defined this region as a PCP-Discontinuity (PCP-D).7 In Figure 3, we outline the cellular events at the PCP-D as proposed by our Bid-Bip model.

Figure 3.

A Bidirectional-Biphasic (Bid-Bip) model for PCP signaling in the Drosophila wing. All diagrams and micrographs represent the dorsal wing surface surrounding the normal position of the L3 vein, which is the site of a PCP-Discontinuity (PCP-D) in the wing (see main text). Anterior is uppermost, distal to the right. For clarity, all diagrams and micrographs are of wings that lack the L3 vein. (A) At the time of the Fz(Sple) signal, symmetric gradients of Dachsous (Ds) expression (blue) are centered on the PCP-D. The Ds gradients control the direction of the Fz(Sple), which points towards high Ds levels. (Note that we arbitrarily define the direction of Fz PCP signaling as the hair polarity that would be specified by the signal). (B) Cells posterior to the PCP-D organize ridges orthogonal to the direction of the Fz(Sple) signal. (C) The Fz(Pk) signal re-polarizes wing cells to point distally. (D) Ridges in the anterior wing are organized orthogonal to the Fz(Pk) signal and wing hairs are specified in the same direction as the Fz(Pk) signal. (E) Composite micrograph showing ridge orientation (red) and hair polarity on a wild-type wing. (F) In the absence of the Pk protein isoform (i.e., a pricklepk mutant), the Fz(Pk) signal fails to occur. Ridge and hair orientation are determined by the Fz(Sple) signal. (G) Composite micrograph showing ridge orientation (red) and hair polarity on a pricklepk mutant wing.

At the time of the early Fz PCP signal, there are symmetric gradients of the protocadherin Dachsous (Ds) centered on the site of the L3 vein.7,15 The Ds gradients control the direction of the Early Fz PCP signal which points towards high Ds levels, i.e., towards the L3 vein (Fig. 3A). (Note that we arbitrarily define the direction of the Fz PCP signal as the hair polarity that would be specified by the signal). This early Fz signal is characterized by the use of the Sple isoform of the PCP protein Prickle within the Fz PCP pathway16 and, for this reason, we refer to it as Fz(Sple) signal. Following the Fz(Sple) signal, cells posterior to the L3 vein organize ridges orthogonal to the direction of the Fz(Sple) signal, i.e., aligned with the P-D axis (Fig. 3B). The late Fz PCP signal then repolarizes cells to point distally (Fig. 3C). The late Fz PCP signal is characterized by the use of the Pk isoform of the Prickle protein,16 and so we refer to it as Fz(Pk) signal. Following the Fz(Pk) signal, cells anterior to the L3 vein organize ridges orthogonal to the direction of the Fz(Pk) signal, i.e., aligned with the A-P axis (Fig. 3D and E). In addition, cells anterior and posterior to the L3 vein form wing hairs that point in the same direction as the Fz(Pk) signal, i.e., towards the distal wing tip.

In the absence of the Pk isoform (i.e., in a pricklepk mutant wing), the Fz(Pk) signal fails to occur and so both ridge orientation and hair polarity are determined by the Fz(Sple) signal alone (Fig. 3A). Consequently, on a pricklepk mutant wing, hairs point in the same direction as the Fz(Sple) signal, i.e., towards the L3 vein (Fig. 3F and G). Ridges are organized orthogonal to the Fz(Sple) signal and so are aligned with the P-D axis in both the anterior and posterior wing. Consequently, a surprising feature of the pricklepk mutant wing is that hairs and ridges have a consistent, approximately orthogonal, relationship in all parts of the wing.6 This differs from wild-type wings, where the relationship between hair polarity and ridge orientation differs between the anterior and posterior (Fig. 3D and E).

Our concept of an early Fz(Sple) signal and a late Fz(Pk) signal is supported by David Strutt's previous finding that the Pk isoform is only required for late Fz PCP signaling in the wing.17 Strutt also proposed that the Dishevelled (Dsh) protein is involved primarily in late Fz PCP signaling.14,17 However, he acknowledged that this interpretation depends upon the dsh1 allele being null for PCP signaling. Therefore, it remains possible that Dsh is required for the early Fz PCP signal, but that this activity is not compromised by the dsh1 mutation. Either way, Strutt's data points towards a differential requirement for Dsh in the early and late Fz PCP signals. We have found that dsh1 mutant flies have ridges aligned with the P-D axis in both the anterior and posterior wing.6 This resembles a pricklepk mutant in which the early Fz(Sple) signal is active, but the late Fz(Pk) signal is inactive. However, unlike a pricklepk mutant, dsh1 hair polarity does not point consistently towards the 3rd vein. We interpret this to mean that in a dsh1 mutant the early Fz(Sple) signal is largely unaffected, but late Fz(Pk) signaling is disrupted (although not inactive). In common with Strutt, our findings argue for different roles for Dsh in the Fz(Sple) and Fz(Pk) signals.

Frizzled, Fat and All That

The relationship between the Fz PCP and Fat/Dachsous (Ft/Ds) pathways in the control of PCP remains a subject of debate. One model, dubbed the Tree-Amonlirdviman model, proposes that gradients of Ft/Ds pathway activity provide a global signal that controls the direction of local Fz PCP signaling.18 An alternative “Two Pathway” model, based on studies in the Drosophila abdomen and larval denticles, proposes that the Ft/Ds and Fz PCP pathways provide independent input into a cell's planar polarity.19,20 The relative merits of the Tree-Amonlirdviman model and Two Pathway models were discussed in a recent Extra View article in Fly journal.21 How does our data on wing membrane development fit the proposed models?

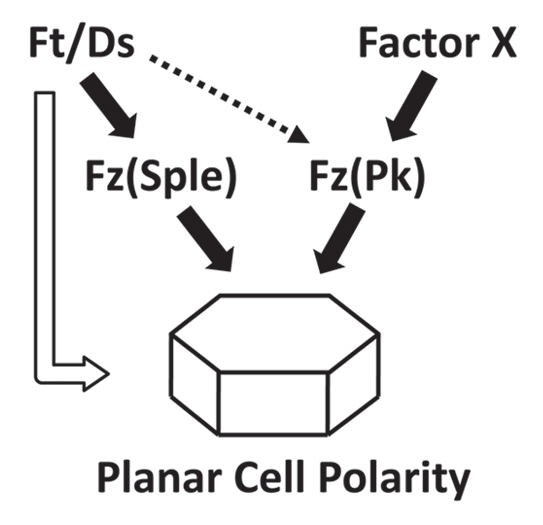

We find that reduced Ft/Ds pathway activity alters the orientation of wing membrane ridges, whereas reduced Fz PCP signaling eliminates membrane ridges.6,7 These findings fit the Tree-Amonlirdviman model as they suggest that the Ft/Ds pathway provides a global signal that controls ridge orientation, whereas the Fz PCP pathway coordinates local cell polarity to allow ridge formation. Furthermore, we find that reduced Ft/Ds activity primarily affects the orientation of membrane ridges in the posterior wing, with relatively little effect on anterior ridge orientation or hair polarity.7 Our Bid-Bip model proposes that posterior ridges are organized by the Fz(Sple) signal and anterior ridges and hairs by the Fz(Pk) signal (Fig. 3). This implies that the Ft/Ds pathway primarily controls the direction of the Fz(Sple) signal, with relatively little influence on the direction of the Fz(Pk) signal (Fig. 4). When we reduce Ft/Ds activity in the absence of the Fz(Pk) signal (i.e., in a pricklepk mutant background), ridge and hair orientation is altered in both the anterior and posterior wing.7 In a pricklepk mutant background, our Bid-Bip model proposes that the Fz(Sple) signal determines ridge orientation and hair polarity in both anterior and posterior (Fig. 3). These results suggest that the Ft/Ds pathway directs Fz(Sple) signaling across the majority of the wing, but has little influence on the direction of the Fz(Pk) signal. In consequence, we resort to proposing that the elusive Factor X is the major global cue controlling Fz(Pk) signaling (Fig. 4). In principle, Factor X could be a conventional morphogen, although there are currently no credible candidates. Alternatively, Factor X might be an intrinsic property or activity of the developing tissue, such as the dynamic ‘cell flow’ described recently in the developing pupal wing.22

Figure 4.

Proposed relationship between the Ft/Ds pathway and two Fz PCP signals in the Drosophila wing. Gradients of Ft/Ds pathway activity direct the orientation of the Fz(Sple) signal. However, the orientation of the Fz(Pk) signal is largely independent of the Ft/Ds pathway, and is presumed to be controlled by an undefined global signal, Factor X. The unshaded arrow represents a direct effect of the Ft/Ds pathway on PCP that we have not observed in the wing, but which has been inferred from studies on the Drosophila adult abdomen and larval denticles.

To summarize, we think that in the developing wing, the Tree-Amonlirdviman model describes the relationship between the Ft/Ds pathway and the Fz(Sple) signal, but not the relationship between Ft/Ds pathway and the Fz(Pk) signal. Our preliminary investigations have not identified an influence of the Ft/Ds pathway on wing PCP that does not involve the Fz PCP pathway, such as described in the Two Pathway model.19 However, we have not looked exhaustively for such effects, and certainly do not exclude such a mechanism (Fig. 4).

In the absence of the Fz(Pk) signal (i.e., in a pricklepk mutant), the Fz(Sple) signal directs wing hairs to point up a gradient of Ds expression (Fig. 3). Similarly, Sple, but not Pk, is required for hairs to point up a Ds gradient in the anterior of a Drosophila abdominal parasegment.23 Furthermore, overexpression of Sple, but not overexpression of Pk, causes hairs to reverse to point up a Ds gradient in the posterior of an abdominal parasegment. Thus, our proposed relationship between Ds activity and the direction of Fz(Sple) signaling in the wing appears to be conserved in the abdomen. In the Drosophila eye, loss of either Ds or Sple activity results in a specific phenotype in which ommatidial chirality and orientation is altered, but the degree of ommatidial rotation remains normal.24,25 In contrast, loss of Pk activity alone does not affect eye development.16 This suggests that Ds and Sple control the same aspects of eye development, which are independent of Pk activity. Taken together, these findings suggest that the specific interactions of the Ft/Ds pathway with Fz(Sple) and Fz(Pk) signaling outlined in Figure 4 may apply to other Drosophila tissues besides the wing. What remains to be determined is what combination of Fz(Sple) and Fz(Pk) signaling are experienced by individual cells during development, and how these signals are integrated to determine a final PCP.

Acknowledgments

We thank David Tree for critical reading of this manuscript. The work described in this article was supported by NSF award 0843028 to Simon Collier.

Extra View to: Hogan J, Valentine M, Cox C, Doyle K, Collier S. Two frizzled planar cell polarity signals in the Drosophila wing are differentially organized by the fat/dachsous pathway. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:1001305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001305.

References

- 1.Gubb D, Garcia-Bellido A. A genetic analysis of the determination of cuticular polarity during development in Drosophila melanogaster. J Embryol Exp Morphol. 1982;68:37–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Seifert JR, Mlodzik M. Frizzled/PCP signalling: a conserved mechanism regulating cell polarity and directed motility. Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:126–138. doi: 10.1038/nrg2042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Eaton S. Cell biology of planar polarity transmission in the Drosophila wing. Mech Dev. 2003;120:1257–1264. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2003.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lawrence PA, Struhl G, Casal J. Planar cell polarity: one or two pathways? Nat Rev Genet. 2007;8:555–563. doi: 10.1038/nrg2125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wansleeben C, Meijlink F. The planar cell polarity pathway in vertebrate development. Dev Dyn. 2011;240:616–626. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.22564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Doyle K, Hogan J, Lester M, Collier S. The Frizzled planar cell polarity signaling pathway controls Drosophila wing topography. Dev Biol. 2008;317:354–367. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2008.02.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogan J, Valentine M, Cox C, Doyle K, Collier S. Two frizzled planar cell polarity signals in the Drosophila wing are differentially organized by the fat/dachsous pathway. PLoS Genet. 2011;7:1001305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wootton RJ. Functional morphology of insect wings. Ann Rev Entomol. 1992;37:113–140. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wootton RJ. The mechanical design of insect wings. Scientific American. 1990;263:114–120. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kiger JA, Jr, Natzle JE, Kimbrell DA, Paddy MR, Kleinhesselink K, Green MM. Tissue remodeling during maturation of the Drosophila wing. Dev Biol. 2007;301:178–191. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghiradella H. Structure of butterfly scales: patterning in an insect cuticle. Microsc Res Tech. 1994;27:429–438. doi: 10.1002/jemt.1070270509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savard J, Tautz D, Richards S, Weinstock GM, Gibbs RA, Werren JH, et al. Phylogenomic analysis reveals bees and wasps (Hymenoptera) at the base of the radiation of Holometabolous insects. Genome Res. 2006;16:1334–1338. doi: 10.1101/gr.5204306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shevtsova E, Hansson C, Janzen DH, Kjaerandsen J. Stable structural color patterns displayed on transparent insect wings. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2011;108:668–673. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017393108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Strutt H, Strutt D. Nonautonomous planar polarity patterning in Drosophila: dishevelled-independent functions of frizzled. Dev Cell. 2002;3:851–863. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(02)00363-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Matakatsu H, Blair SS. Interactions between Fat and Dachsous and the regulation of planar cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Development. 2004;131:3785–3794. doi: 10.1242/dev.01254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gubb D, Green C, Huen D, Coulson D, Johnson G, Tree D, et al. The balance between isoforms of the prickle LIM domain protein is critical for planar polarity in Drosophila imaginal discs. Genes Dev. 1999;13:2315–2327. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.17.2315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Strutt D, Strutt H. Differential activities of the core planar polarity proteins during Drosophila wing patterning. Dev Biol. 2007;302:181–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tree DR, Ma D, Axelrod JD. A three-tiered mechanism for regulation of planar cell polarity. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2002;13:217–224. doi: 10.1016/s1084-9521(02)00042-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Casal J, Lawrence PA, Struhl G. Two separate molecular systems, Dachsous/Fat and Starry night/Frizzled, act independently to confer planar cell polarity. Development. 2006;133:4561–4572. doi: 10.1242/dev.02641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Repiso A, Saavedra P, Casal J, Lawrence PA. Planar cell polarity: the orientation of larval denticles in Drosophila appears to depend on gradients of Dachsous and Fat. Development. 2010;137:3411–3415. doi: 10.1242/dev.047126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lawrence PA. Planar cell polarity: fashioning solutions. Fly (Austin) 2011:5. doi: 10.4161/fly.5.2.14396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aigouy B, Farhadifar R, Staple DB, Sagner A, Roper JC, Julicher F, et al. Cell flow reorients the axis of planar polarity in the wing epithelium of Drosophila. Cell. 2010;142:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lawrence PA, Casal J, Struhl G. Cell interactions and planar polarity in the abdominal epidermis of Drosophila. Development. 2004;131:4651–4664. doi: 10.1242/dev.01351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Choi KW, Mozer B, Benzer S. Independent determination of symmetry and polarity in the Drosophila eye. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:5737–5741. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang CH, Axelrod JD, Simon MA. Regulation of Frizzled by fat-like cadherins during planar polarity signaling in the Drosophila compound eye. Cell. 2002;108:675–688. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00658-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]