Abstract

This study was conducted to find out the status of the ossicles in cases of chronic suppurative otitis media (CSOM). One hundred and fifty cases of CSOM, who underwent surgery, were included and their intra-operative ossicular chain findings noted. Ossicular erosion was found to be much more common in unsafe CSOM than in safe CSOM. Malleus was found to be the most resistant ossicle to erosion whereas incus was found to be the most susceptible.

Keywords: Ossicles, CSOM

Introduction

CSOM, a common condition in otorhinolaryngology, is characterized by chronic, intermittent or persistent discharge through a perforated tympanic membrane. Poor living conditions, overcrowding, poor hygiene and nutrition have been suggested as the basis for the widespread prevalence of CSOM in developing countries [1, 2].

Both types of CSOM, tubotympanic which is considered safe, as well as atticoantral which is considered unsafe, may lead to erosion of the ossicular chain. This propensity for ossicular destruction is much greater in cases of unsafe CSOM, due to the presence of cholesteatoma and/or granulations [3]. The proposed mechanism for erosion is chronic middle ear inflammation as a result of overproduction of cytokines—TNF alpha, interleukin-2, fibroblast growth factor, and platelet derived growth factor, which promote hypervascularisation, osteoclast activation and bone resorption causing ossicular damage. TNF-alpha also produces neovascularisation and hence granulation tissue formation. CSOM is thus an inflammatory process with a defective wound healing mechanism [4]. This inflammatory process in the middle ear is more harmful the longer it stays and the nearer it is to the ossicular chain [5].

Pathologies that interrupt the ossicular chain result in large hearing losses. Complete disruption of the ossicular chain can result in a 60 dB hearing loss [6, 7]. We present here the intra-operative ossicular chain status of 150 cases of CSOM who underwent surgery, at our institution over a 12 month period.

Materials and Methods

This was a prospective study, carried out in the Department of Otorhinolaryngology, Himalayan Institute of Medical Sciences, Dehradun, a tertiary care centre in the state of Uttarakhand, from November 2007 to October 2008. A total of 150 patients were included in this study.

Patients aged more than 16 years, diagnosed with CSOM and posted for middle ear surgery were included. Patients who were less than 16, had malignancy of middle ear, otitis externa or previous history of ear surgery were excluded.

The selected patients were subjected to a detailed history and complete ENT examination. The ears were examined by otoscopy initially and subsequently by a microscope and otoendoscope to establish a preoperative diagnosis of safe or unsafe disease.

All patients underwent a preoperative pure tone audiometry, to find out the hearing status and obtain documentary evidence for the same, and X-ray mastoid (bilateral Schueller’s view) to assess the pathology and surgical anatomy of the mastoid. Intra-operative middle ear findings including ossicular chain status, erosion of the individual ossicles, and continuity of the malleo-incudal and incudo-stapedial joint were noted.

The ossicular chain status in safe and unsafe ear was compared statistically. Chi square test was used to evaluate the level of significance and the P value <0.05 was considered as significant.

Results

A total of 150 cases were selected for this study and divided into ‘safe’ and ‘unsafe’ CSOM based on the history and clinical findings. The number of cases with safe CSOM was 96 (64.00%) and that with unsafe CSOM was 54 (36.00%). The patients were aged between 16 and 70 years. The mean age was 29.78 years with SD 13.09. The number of cases in the 16–25 years age group was 77 (51.33%), and this formed the largest group in the study. The number of male and female patients was 72 (48.00%) and 78 (52.00%). The right ear was operated in 78 (52.00%) cases and left ear in 72 (48.00%) cases.

The primary complaints of the patients were ear discharge, seen in 100% of the cases and hearing loss, seen in 88.67% of the cases. The duration of ear discharge ranged from 6 months to 50 years, with 39 cases (26.00%) having duration between 10 and 15 years. In safe CSOM, 26 (32.29%) cases had duration of ear discharge ranging from 1 to 5 years. In unsafe CSOM, 17 (35.19%) had discharge duration from 10 to 15 years.

Duration of hearing loss varied from patients who did not complain of any hearing loss to those who had the complaint for about 40 years. Maximum number, 50 (33.33%) cases complained of hearing loss from 1 to 5 years while 17 (11.33%) cases had no hearing loss. In safe CSOM 31 (32.39%) cases and in unsafe CSOM 17 (35.19%) cases were in this category.

Intra-Operative Findings

Based on the intra-operative findings, the patients were reclassified into those with safe CSOM, 90 (60.00%) cases, and those with unsafe CSOM, 60 (40.00%) cases. Six (4.00%) cases which were clinically diagnosed as safe were found to be unsafe, intra-operatively.

Ossicular Status

Malleus (Table 1)

Table 1.

Status of malleus in CSOM

| Malleus | CSOM (%) n = 150 | Safe (%) n = 90 | Unsafe (%) n = 60 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact | 121 (80.67) | 88 (97.78) | 33 (55.00) | 0.028* |

| HOM necrosed | 18 (12.00) | 2 (2.22) | 16 (26.67) | 0.000* |

| Head necrosed | 4 (2.67) | – | 4 (6.67) | 0.016* |

| Handle + head necrosed | 1 (0.66) | – | 1 (1.66) | 0.223 |

| Absent | 6 (4.00) | – | 6 (10.00) | 0.004* |

| Total | 150 (0.00) | 90 (100.00) | 60 (100.00) |

* P value < 0.05 is significant

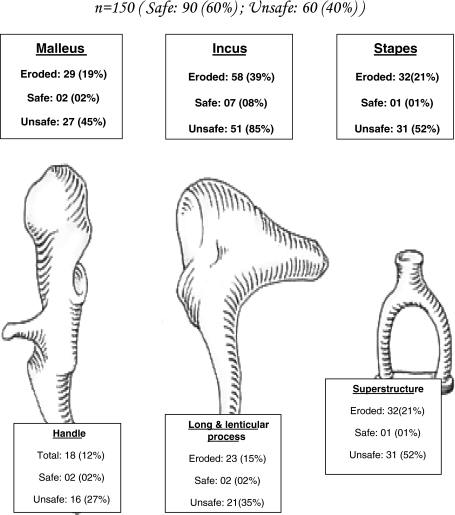

The malleus was found to be the most resistant ossicle to erosion in CSOM. It was found intact in 121 (80.67%), eroded in 23 (15.33%) and absent in 6 (4.00%) of the cases. In safe CSOM, 88 (97.78%) of the cases had an intact malleus while in 2 (2.22%) cases the tip of handle of malleus was found necrosed. In unsafe CSOM, the malleus was found intact in 33 (55.00%), necrosed in 21 (35.00%) and absent in 6 (10.00%) cases.

Incus (Table 2)

Table 2.

Status of incus in CSOM

| Incus | CSOM (%) n = 150 | Safe (%) n = 90 | Unsafe (%) n = 60 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact | 92 (61.33) | 83 (92.23) | 9 (15.00) | 0.000* |

| Absent | 26 (17.33) | 2 (2.22) | 24 (40.00) | 0.000* |

| Long + lenticular process necrosed | 23 (15.33) | 2 (2.22) | 21 (35.00) | 0.000* |

| Lenticular process necrosed | 4 (2.66) | 3 (3.33) | 1 (0.67) | 0.545 |

| Short process necrosed | 1 (0.67) | – | 1 (0.67) | 0.223 |

| Body + long process necrosed | 1 (0.67) | – | 1 (0.67) | 0.223 |

| Body + lenticular process necrosed | 1 (0.67) | – | 1 (0.67) | 0.223 |

| Long + short process necrosed | 1 (0.67) | – | 1 (0.67) | 0.223 |

| Lenticular + short process necrosed | 1 (0.67) | – | 1 (0.67) | 0.223 |

| Total | 150 (100.00) | 90 (100.00) | 60 (100.00) |

* P value < 0.05 is significant

Incus was the ossicle most commonly found eroded in our study. We found the incus intact in 92 (61.33%), eroded in 32 (21.34%) and absent in 26 (17.33%) cases. The most commonly necrosed parts of the incus were the lenticular process in 29 (19.33%) and the long process in 25 (16.67%) of the cases. In safe CSOM, the incus was found intact in 83 (92.23%), eroded in 5 (5.55%), and absent in 2 (2.22%) cases. Lenticular process was the most commonly necrosed part of the incus and was found eroded in 5 (5.55%) cases.

In unsafe CSOM, the incus was found intact in 9 (15.00%), necrosed in 27 (45.00%) and absent in 24 (40.00%) cases. Lenticular process was, once again, the most commonly necrosed part of the incus and was found eroded in 24 (40.00%) cases, followed closely by the long process, which was eroded in 23 (38.33%) cases.

Stapes (Table 3)

Table 3.

Status of stapes in CSOM

| Stapes | CSOM (%) n = 150 | Safe (%) n = 90 | Unsafe (%) n = 60 | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intact | 118 (78.67) | 89 (98.89) | 29 (48.33) | 0.008* |

| Superstructure necrosed | 32 (21.33) | 1 (1.11) | 31 (51.67) | 0.000* |

| Total | 150 (100.00) | 90 (100.00) | 60 (100.00) |

* P value < 0.05 is significant

Stapes was found intact in 118 (78.67%) cases while in 32 (21.33%), the superstructure of stapes was found eroded by the disease. In safe CSOM, 89 (98.89%) of the cases had an intact stapes and only 1 (1.11%) case had erosion of the superstructure. In unsafe CSOM, 29 (48.33%) cases had an intact stapes and 31 (51.67%) showed erosion of the superstructure of stapes.

Status of Malleo-Incudal (MI) and Incudo-Stapedial (IS) Joint

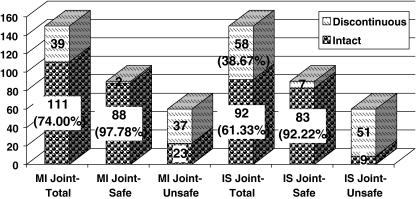

The malleo-incudal joint was found intact in 111 (74.00%) and discontinuous in 39 (26.00%) cases. In safe CSOM, malleo incudal joint was intact in 88 (97.78%) cases. In unsafe CSOM, malleo incudal joint was and discontinuous in 37 (61.67%) cases.

The incudo-stapedial joint was found intact in 92 cases (61.33%) and discontinuous in 58 (38.67%) cases of CSOM. In safe CSOM, it was intact in 83 (92.22%) cases of the cases and discontinuous in 7 (7.78%). In unsafe CSOM, it was intact only in 9 (15.00%) cases and discontinuous in 51 (85.00%) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Status of MI and IS joint in CSOM

Status of Ossicular Chain

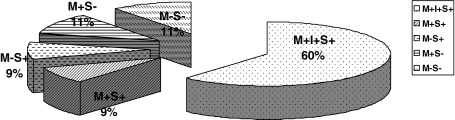

The ossicular chain was found intact (M+I+S+) in 92 (61.34%) cases. In safe CSOM, 83 cases (92.22%) had an intact chain, 7 cases (7.77%) had ossicular damage. In unsafe CSOM, intact malleus with eroded incus and stapes (M+S−) was seen in 16 (26.67%) cases, followed by M−S− in 15 cases (25.00%) (Figs. 2, 3).

Fig. 2.

Status of ossicular chain in CSOM

Fig. 3.

Ossicular chain necrosis in CSOM

Discussion

In this study we studied a total of 150 patients of CSOM to assess the intra-operative ossicular status.

The cases were divided clinically into safe CSOM, 96 (64.00%) cases, and unsafe CSOM, 54 (36.00%) cases. Intra-operatively, 90 (60.00%) cases were found to be safe and 60 (40.00%) cases to be unsafe. Six (4.00%) cases which were clinically diagnosed as safe were found to be unsafe intra-operatively.

The most commonly affected age group was between 16 and 25 years, as observed by various other studies also [8–10]. The early presentation may be due to increased awareness to health issues and difficulty in hearing affecting the work efficiency, leading patients and parents to seek early medical intervention. The ratio of male to female patients was 1.00:1.08. Similar findings have been reported by several other authors [11–13]. The reason for higher number of females may be that in hilly areas females do most of the outdoor work and hence are more prone to atmospheric and climate changes. More than 80% districts in the state of Uttarakhand belong to hilly areas and form a large percentage of the population that we cater to.

The duration of ear discharge ranged from 6 months to 50 years (Mean duration 11.30 years). Thirty-nine (26.00%) cases had duration of ear discharge between 10 and 15 years. The duration of disease in unsafe cases was generally seen to be longer. This particular finding may be a result of conversion of safe type of disease into unsafe disease over time [14].

The duration of hearing loss was in all cases found to be lesser than the duration of discharge. This may be attributed to difficulty in appreciating minor degrees of hearing loss by the patient. The hearing loss would be noticed only when the disease has progressed sufficiently to cause a significant impairment of hearing by perforation or ossicular destruction.

Malleus was found to be the most resistant ossicle, found intact in 121 (80.67%) cases in our study. It was eroded in 23 (15.33%) and absent in 6 (4.00%) cases. The handle of malleus in 19 (12.66%) cases, was the most commonly necrosed part of malleus. In safe CSOM, malleus was intact in 88 (97.78%) and eroded in 2 (2.22%) cases. In unsafe CSOM, malleus was intact in 33 (55.00%), eroded in 21 (35.00%) and absent in 6 (10.00%). These findings were consistent with those of Udaipurwala et al. [15]. Sade et al. found a higher incidence, around 06.00%, of erosion of malleus in cases of safe CSOM. In unsafe disease they found malleus necrosis in 26.00% cases which correlates well with our finding [5].

Incus was observed to be the most common ossicle to get necrosed in cases of CSOM. In our study, incus was found intact in 92 (61.33%) cases, eroded in 32 (21.34%) cases and absent in 26 (17.33%) cases. The commonest defect was erosion of the lenticular process in 29 (19.33%) cases followed by long process in 25 (16.67%) cases. In safe CSOM, incus was intact in 83 (92.23%) cases, eroded in 5 (5.55%) cases and absent in 2 (2.22%) cases while in unsafe CSOM it was intact in 9 (15.00%) cases, eroded in 27 (45.00%) cases and absent in 24 (40.00%) cases. The most frequently involved parts were again the lenticular process (40.00%) and the long process (38.33%) of incus. Udaipurwala et al. had a very similar incidence of necrosis of the incus at 41.00%. The long process of incus was found to be the most commonly necrosed part as compared to our study where lenticular process was more commonly necrosed. This can be explained, as Udaipurwala et al. have probably considered the lenticular process to be a part of the long process of incus, since they have not mentioned it separately [15]. Austin reported the most common ossicular defect to be the erosion of incus, with intact malleus and stapes, in 29.50% cases [16]. Kartush found erosion of long process of incus with an intact malleus handle and stapes superstructure (type A) as the most common ossicular defect [17]. Shreshtha et al. and Mathur et al. also reported similar findings in unsafe CSOM [18, 19].

Stapes was found intact in 118 (78.67%) cases and involvement of stapes superstructure was noted in 32 (21.33%) cases of CSOM. The footplate was found intact in all cases. In safe CSOM, stapes was found intact in 89 (98.89%) cases and eroded in 1 (1.11%) case. In unsafe CSOM, stapes was intact in 29 (48.33%) cases and eroded in 31 (51.67%) cases.

The incidence of stapedial necrosis in our study was found to be very similar to the study by Udaipurwala et al. They found the superstructure to be necrosed in 21.00% cases, which matches with our findings [15]. Austin reported erosion of stapes at around 15.50% [16]. Sade et al. reported stapes involvement in unsafe CSOM to be 36.00% [5]. Shreshtha et al. found involvement of stapes superstructure in 15.00% cases of unsafe CSOM [18]. Motwani et al. reported stapes arch necrosis in 30.00% cases of CSOM [20].

We found an intact and mobile ossicular chain (M+I+S+) in 92 (61.34%) of our cases. In safe CSOM the ossicles were mostly intact. M+S+ configuration was found in 5.55%. M−S+ and M−S− both were 1.11% each. In unsafe CSOM, we found only 9 (15.00%) cases with intact ossicular chain. M+S+ was seen in 8 (13.33%) cases, M−S+ in 12 (20.00%) cases, M+S− in 16 (26.67%) cases and M−S− in 15 (25.00%) cases. These findings were in tandem with those of Dasgupta et al. in two studies on unsafe CSOM. Toran et al. reported similar findings of ossicular chain in M−S− category [21–23].

Conclusion

In this study we found the malleus to be the most resistant ossicle to erosion in chronic suppurative otitis media whereas incus was found to be the most susceptible. The incidence of ossicular erosion was found to be much greater in unsafe CSOM than in safe CSOM.

References

- 1.Slattery WH. Pathology and clinical course of inflammatory diseases of the middle ear. In: Glasscock ME, Gulya AJ, editors. Glasscock-Shambaugh surgery of the ear. 5. New Delhi: Reed Elsevier India Pvt. Ltd; 2003. pp. 428–429. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mills RP. Management of chronic suppurative otitis media. In: Booth JB, Kerr AG, editors. Scott-Brown’s otolaryngology. 6. London: Reed Educational and Professional Publishing limited; 1997. p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Proctor B. The development of middle ear spaces and their surgical significance. J Laryngol Otol. 1964;78:631–648. doi: 10.1017/S002221510006254X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deka RC. Newer concepts of pathogenesis of middle ear cholesteatoma. Indian J Otol. 1998;4(2):55–57. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sade J, Berco E, Buyanover D, Brown M. Ossicular damage in chronic middle ear inflammation. Acta Otolaryngol. 1981;92:273–283. doi: 10.3109/00016488109133263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bojrab DI, Balough BJ. Surgical anatomy of the temporal bone and dissection guide. In: Glasscock ME, Gulya AJ, editors. Glasscock-Shambaugh surgery of the ear. 5. New Delhi: Reed Elsevier India Pvt. Ltd; 2003. p. 778. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Merchant SN, Rosowski JJ. Auditory physiology. In: Glasscock ME, Gulya AJ, editors. Surgery of the ear. 5. New Delhi: Reed Elsevier India Pvt. Ltd; 2003. p. 70. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shreshtha S, Sinha BK. Hearing results after myringoplasty. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2006;4(4):455–459. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh RK, Safaya A. Middle ear hearing restoration using autologous cartilage graft in canal wall down mastoidectomy. Indian J Otol. 2005;11:10–14. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ajalloueyan M. Experience with surgical management of cholesteatomas. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:931–933. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.9.931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang HM, Lin JC, Lee KW, Tai CF, Wang LF, Chang HM, et al. Analysis of mastoid findings at surgery to treat middle ear cholesteatoma. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132:1307–1310. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.12.1307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vos C, Gersdorff M, Gerard JM. Prognostic factors in ossiculoplasty. Otol Neurotol. 2007;28(1):61–67. doi: 10.1097/01.mao.0000231598.33585.8f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marfani MS, Magsi PB, Thaheem K. Ossicular damage in chronic suppurative otitis media—study of 100 cases. Pak J Otolaryngol. 2005;21(1):9–11. [Google Scholar]

- 14.El-Sayed Y. Bone conduction impairment in uncomplicated chronic suppurative otits media. Am J Otolaryngol. 1998;19(3):149–153. doi: 10.1016/S0196-0709(98)90079-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Udaipurwala IH, Iqbal K, Saqulain G, Jalisi M. Pathlogical profile in chronic suppurative otitis media—the regional experience. J Pak Med Assoc. 1994;44(10):235–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Austin DF. Ossicular reconstruction. Arch Otolaryngol. 1971;94:525–535. doi: 10.1001/archotol.1971.00770070825007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kartush JM. Ossicular chain reconstruction. Capitulum to malleus. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 1995;27:689–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shrestha S, Kafle P, Toran KC, Singh RK. Operative findings during canal wall mastoidectomy. Gujarat J Otorhinolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;3(2):7–9. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mathur NN, Kakar P, Singh T, Sawhney KL. Ossicular pathology in unsafe chronic otitis media. Indian J Otolaryngol. 1991;43(1):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Motwani G, Batra K, Dravid CS. Hydroxylapatite versus teflon ossicular prosthesis: our experience. Indian J Otol. 2005;11:12–16. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dasgupta KS, Gupta M, Lanjewar KY. Pars tensa cholesteatoma: the underestimated threat. Indian J Otol. 2005;11:17–20. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dasgupta KS, Joshi SV, Lanjewar KY, Murkey NN. Pars tensa & attic cholesteatoma: are these the two sides of a same coin? Indian J Otol. 2005;11:22–26. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Toran KC, Shrestha S, Kafle P, Deyasi SK. Surgical management of Sinus tympani cholesteatoma. Kathmandu Univ Med J. 2004;2(4):297–300. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]