Abstract

Objective

Little is known about the possible impacts of neighborhood socioeconomic status on birth outcomes and infant mortality among Aboriginal populations. We assessed birth outcomes and infant mortality by neighborhood socioeconomic status among First Nations and non-First Nations in Manitoba.

Study Design

We conducted a retrospective birth cohort study of all live births (26,176 First Nations, 129,623 non-First Nations) to Manitoba residents, 1991–2000. Maternal residential postal codes were used to assign four measures of neighborhood socioeconomic status (concerning income, education, unemployment, and lone parenthood) obtained from 1996 census data.

Results

First Nations women were much more likely to live in neighborhoods of low socioeconomic status. First Nations infants were much more likely to die during their first year of life [risk ratio (RR) =1.9] especially during the postneonatal period (RR=3.6). For both First Nations and non-First Nations, living in neighborhoods of low socioeconomic status was associated with an increased risk of infant death, especially postneonatal death. For non-First Nations, higher rates of pre-term and small-for-gestational-age birth were consistently observed in low socioeconomic status neighborhoods, but for First Nations the associations were less consistent across the four measures of socioeconomic status. Adjusting for neighborhood socioeconomic status, the disparities in infant and postneonatal mortality between First Nations and non-First Nations were attenuated.

Conclusion

Low neighborhood socioeconomic status was associated with an elevated risk of infant death even among First Nations, and may partly account for their higher rates of infant mortality compared to non-First Nations in Manitoba.

Keywords: Aboriginal health, first nations, neighborhood socioeconomic status, birth outcome, infant mortality

INTRODUCTION

Reducing health inequalities is an important goal of public health initiatives. However, development of appropriate and effective intervention programs has been a challenge partly because of insufficient data on vulnerable subpopulations [1]. Aboriginal populations are the most vulnerable group to poor health outcomes in many countries. Low socioeconomic status is generally much more prevalent in Aboriginal populations, and is most likely so for pregnant Aboriginal women [2]. Many studies have documented that low socioeconomic status at the individual or neighborhood level is associated with poor health outcomes [3–8]. However, population-based data on socioeconomic status and birth outcomes among Aboriginal populations are scarce. We are unaware of any analyses of neighborhood socioeconomic status and birth outcomes among Aboriginal populations. In this study, we assessed birth outcomes and infant mortality by neighborhood socioeconomic status among First Nations and non-First Nations in the province of Manitoba, Canada, a setting with universal health insurance. We also wanted to know whether neighborhood socioeconomic status might partly account for the higher rates of adverse birth outcomes and infant mortality among First Nations compared to non-First Nations populations.

STUDY DESIGN

Subjects

This was a retrospective birth cohort study using Statistics Canada’s linked birth and infant death database for live births to residents of Manitoba, 1991–2000. The validity of the Canadian linked vital data has been well documented [9]. Stillbirths were excluded because questions on First Nations identification were not asked on stillbirth registrations in Manitoba. We excluded births (0.5%) with missing birth weight, gestational age, sex, or postal code of the usual place of residence (needed for determining neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics), or with a gestational age <20 weeks or birth weight <500 grams, leaving 155,799 births (26,176 First Nations, 129,623 non-First Nations) remaining for analysis. Available individual-level variables on maternal and birth characteristics included maternal age, ethnicity (First Nations, other), marital status, parity, plurality, infant sex, gestational age (in completed weeks), and birth weight (in grams). A birth was considered a First Nations birth if the mother or father self-identified as First Nations (“Registered Indian” via a self identification checkbox and/or write in of treaty number or band name) on the live birth registration (89% were classified based on the maternal identifier). Individual informed consent was not sought because the study was based on anonymous birth registration data. Research ethics board approval was obtained from Sainte-Justine Hospital of the University of Montreal. The study was approved by the Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs - Health Information Research Governance Council.

Geocoding Census Geography

We assigned each birth to the corresponding census enumeration area and census metropolitan area or census agglomeration through geocoding based on the postal code of the mother’s place of residence [10]. An enumeration area typically consists of 125 to 440 dwellings of relatively homogenous socioeconomic status [11]. Census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations are economic communities of 10,000 or more persons, which include adjacent districts with high commuting flows into the central area. All census metropolitan areas and census agglomerations were considered urban, while the remaining areas (with less than 10,000 population in 1996) were considered rural [12].

Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status

We defined neighborhood socioeconomic conditions at the enumeration area level according to four indicators: income (household-size adjusted income per single person equivalent), education (% of adults who had not completed high school), unemployment (% unemployed in the work force), and lone parent families (% of single parent families among all families with children at home), based on census data for 1996 (the middle year of the study period). We grouped enumeration areas by each of the four indicators into quintiles of births (5 groups) in rural and urban areas separately. Areas belonging to the lowest socioeconomic status quintile according to each indicator (for example, the lowest neighborhood income quintile within rural areas) were considered the “exposure” group, while all other quintiles together were the reference group. We used various dimensional rather than composite neighborhood socioeconomic status indicators since the “social” implications of various socioeconomic status component indicators (such as living as a single parent) may be different for women living in First Nations communities versus in the general population.

Outcomes and Analyses

Main outcomes were preterm (<37 completed weeks gestational age), small-for-gestational-age (<10th percentile, based on a recent Canadian fetal growth standard [13]) or large-for-gestational-age (>90th percentile) birth, infant death (0–364 days of postnatal life), neonatal death (0–27 days), and postneonatal death (28–364 days). Causes of infant death were grouped according to the classification of the International Collaborative Effort on Perinatal and Infant Mortality [14], based on International Classification of Diseases (ICD)-9 codes for births in 1991–1999 or ICD-10 codes for births in 2000. Crude and adjusted odds ratios (ORs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were compared to assess the potential confounding effects of other variables. Two sets of adjusted odds ratios (ORs) were calculated in multivariate logistic regressions: adjusted ORs controlling for individual-level characteristics (maternal age, marital status, parity, infant sex, multiple pregnancy, and rural versus urban residence); and adjusted ORs further controlling for neighborhood socioeconomic status (income, education, unemployment, and lone parents) in multilevel logistic regression models.

RESULTS

Maternal and Neighborhood Characteristics

Large differences were observed among First Nations versus non-First Nations in Manitoba with respect to maternal and neighborhood characteristics (Table 1). First Nations mothers were about three times more likely to be young (<20 years of age) or unmarried, but less likely to be older (≥35 y) or primiparous. Neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics were much worse for First Nations compared to non-First Nations. In rural areas, the median income per single person equivalent was 40% lower, the unemployment rate 5 times as high, the percentage of lone parents nearly twice as high in the places where First Nations lived compared to the places where non-First Nations lived, while these differences were smaller in urban areas. In both rural and urban areas, the percentage of adults who had not completed high school was about 1/3 higher in the places where First Nations lived compared to the places where non-First Nations lived. First Nations were much more likely to live in neighborhoods ranking lowest in terms of the various measures of socioeconomic status: they were 3.8 times more likely to live in the poorest neighborhood income quintile, 3 times more likely to live in the lowest neighborhood education quintile, and 3.4 times more likely to live in the neighborhood quintile with the highest unemployment rates.

Table 1.

Maternal and Neighborhood Socioeconomic Characteristics Among First Nations and Non-First Nation Births in Manitoba, 1991–2000

| First Nations (n=26,176) | Non-First Nations (n=129,623) | First Nations/Non-First Nations ratio§ | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Maternal characteristics | |||

| Age <20 y, % | 24.4 | 7.4 | 3.30 |

| ≥35 y, % | 4.8 | 11.4 | 0.42 |

| Unmarried, % | 73.6 | 25.7 | 2.86 |

| Primiparous, % | 28.7 | 43.0 | 0.67 |

| Neighborhood characteristics* | |||

| Rural areas | |||

| Income, per single person equivalent $ | 15,568 | 26,256 | 0.59 |

| Lone parents, % | 25.0 | 14.0 | 1.79 |

| Unemployment, % | 28.0 | 5.6 | 5.00 |

| Low education, % | 70.4 | 52.3 | 1.35 |

| Urban areas | |||

| Income, per single person equivalent $ | 24,538 | 29,999 | 0.82 |

| Lone parents, % | 29.6 | 24.1 | 1.23 |

| Unemployment, % | 8.8 | 7.3 | 1.21 |

| Low education, % | 50.0 | 35.9 | 1.39 |

| % in the neighborhood quintile* of: | |||

| Lowest income | 75.5 | 20.0 | 3.78 |

| Lowest education | 49.8 | 16.7 | 2.98 |

| Highest % lone parents | 42.5 | 19.0 | 2.24 |

| Highest unemployment rate | 54.3 | 15.9 | 3.41 |

Neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics based on census data for 1996, the middle year of the study period. Neighborhood quintiles determined separately for rural and urban areas. Income was based on the mean income per single person equivalent; lone parents compared to all families with children at home. Unemployed compared to labour force; adults with education less than completed high school compared to all adults. See Methods for details.

The ratios for all comparisons shown were significant at p<0.001.

Birth Outcomes and Infant Mortality

Overall, First Nations births were 12% more likely to be preterm, but 20% less likely to be small-for-gestational-age, and 60% more likely to be large-for-gestational-age (Table 2). Comparing First Nations to non-First Nations, Infant mortality rates roughly doubled, and the disparities changed very little from the earlier (1991–1995) to later (1996–2000) study period. All other results showed similar patterns for the earlier (1991–1995) and later (1996–2000) study periods. Therefore, we present all subsequent results for the total study cohort. The higher infant mortality rates among First Nations were largely due to higher postneonatal mortality (3.6 times as high), while the difference in neonatal mortality rates was small and not statistically significant. Comparing First Nations to non-First Nations, significantly higher risks of infant death were observed for congenital anomalies (1.7 times as high), postneonatal SIDS (4.5 times as high), and infections (2.6 times as high). The largest absolute risk differences in cause-specific infant death were observed for congenital anomalies (risk difference =1.1 per 1000) and SIDS (risk difference = 1.4 per 1000).

Table 2.

Birth Outcomes and Infant Mortality for First Nations Versus Non-First Nations Births in Manitoba, 1991–2000

| First Nations (n= 26,176) |

Non-First Nations (n=129,623) |

Risk Difference | RR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| Births (%) | ||||

| Preterm | 8.2 | 7.3 | 0.9 | 1.12 (1.07, 1.17) * |

| Small-for-gestational-age | 7.8 | 9.8 | 2.0 | 0.79 (0.76, 0.83) * |

| Large-for-gestational-age | 17.8 | 11.3 | 6.5 | 1.58 (1.54, 1.63) * |

| Deaths (per 1000) | ||||

| Neonatal mortality | 3.7 | 3.3 | 0.4 | 1.12 (0.90, 1.39) |

| Postneonatal mortality | 6.1 | 1.7 | 4.4 | 3.57 (2.91, 4.38)* |

| Infant mortality | 9.8 | 5.0 | 4.8 | 1.94 (1.68, 2.25)* |

| 1991–1995 | 9.8 | 5.2 | 4.6 | 1.89 (1.53, 2.33)* |

| 1996–2000 | 9.8 | 4.8 | 5.0 | 2.02 (1.65, 2.46)* |

| Causes of infant death: | ||||

| Congenital anomalies | 2.9 | 1.8 | 1.1 | 1.66 (1.29, 2.15)* |

| Immaturity-related conditions |

0.9 | 1.1 | −0.2 | 0.76 (0.49, 1.19) |

| Neonatal asphyxia | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.2 | 1.41 (0.74, 2.69) |

| Postneonatal SIDS | 1.8 | 0.4 | 1.4 | 4.47 (3.00, 6.65)* |

| Infections | 0.8 | 0.3 | 0.5 | 2.61 (1.52, 4.48)* |

RR = risk ratio; CI= 95% confidence interval.

P<0.05.

Birth Outcomes by Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status

Neighborhood Income

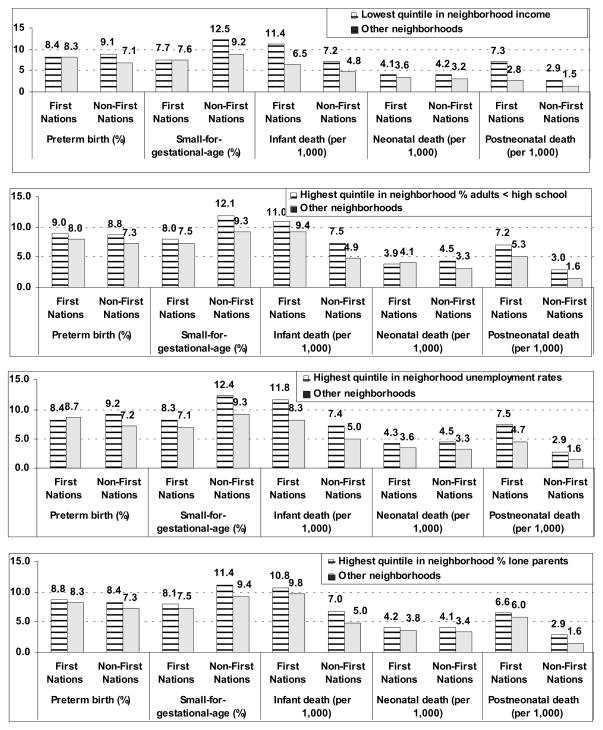

Risks of infant death and especially postneonatal death showed substantial differences according to neighborhood income among both First Nations and non-First Nations, and larger risk differences among First Nations (Table 3, Fig. 1). Comparing the poorest neighborhood income quintile versus all other neighborhoods, the RRs were 1.8 for infant death and 2.6 for post-neonatal death for First Nations, and were 1.5 for infant death and 1.9 for postneonatal death for non-First Nations. For non-First Nations, substantially higher risks of preterm or small-for-gestational-age birth were observed in the poorest neighborhood income quintile compared to all other neighborhoods, while there were virtually no such risk differences for First Nations.

Table 3.

Crude Relative Risks§ (95% Confidence Interval) of Adverse Birth Outcomes and Infant Mortality Comparing the Lowest Socioeconomic Status Quintile Versus All Other Neighborhoods, for First Nations and Non-First Nations in Manitoba, 1991–2000

| Outcome | RR (95% CI) for the lowest socioeconomic status quintile versus all other neighborhoods in:

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Income | Education | Unemployment | Lone parents | |

|

| ||||

| Births | ||||

| Preterm | ||||

| First Nations | 1.01 (0.92, 1.11) | 1.13 (1.05, 1.22)* | 0.96 (0.89, 1.04) | 1.06 (0.98, 1.15) |

| Non-First Nations | 1.27 (1.21, 1.33)* | 1.21 (1.15, 1.27)* | 1.27 (1.21, 1.33)* | 1.15 (1.10, 1.21)* |

| Small-for-gestational-age | ||||

| First Nations | 1.02 (0.93, 1.13) | 1.07 (0.99, 1.17) | 1.17 (1.08, 1.27)* | 1.07 (0.99, 1.16) |

| Non-First Nations | 1.36 (1.31, 1.41)* | 1.30 (1.25, 1.35)* | 1.33 (1.27, 1.38)* | 1.20 (1.16, 1.25)* |

| Large-for-gestational-age | ||||

| First Nations | ||||

| Non-First Nations | 0.98 (0.93, 1.05) | 0.97 (0.92, 1.02) | 0.93 (0.89, 0.98)* | 0.92(0.87, 0.97)* |

| Deaths | 0.91 (0.88, 0.95)* | 0.92 (0.88, 0.96)* | 0.93 (0.89, 0.97)* | 0.94 (0.90, 0.97)* |

| Neonatal | ||||

| First Nations | 1.13 (0.71, 1.79) | 0.95 (0.66, 1.38) | 1.19 (0.82, 1.73) | 1.11 (0.76, 1.61) |

| Non-First Nations | 1.31 (1.05, 1.63)* | 1.35 (1.09, 1.69)* | 1.34 (1.07, 1.68)* | 1.21 (0.97, 1.50) |

| Postneonatal | ||||

| First Nations | 2.57 (1.57, 4.19)* | 1.35 (0.99, 1.82) | 1.59 (1.16, 2.17)* | 1.09 (0.80, 1.46) |

| Non-First Nations | 1.93 (1.46, 2.55)* | 1.85 (1.39, 2.46)* | 1.76 (1.31, 2.36)* | 1.84 (1.40, 2.43)* |

| Infant | ||||

| First Nations | 1.76 (1.26, 2.45)* | 1.18 (0.93, 1.48) | 1.41 (1.11, 1.80)* | 1.09 (0.87, 1.38) |

| Non-First Nations | 1.51 (1.27, 1.79)* | 1.52 (1.27, 1.80)* | 1.48 (1.24, 1.77)* | 1.41 (1.19, 1.67)* |

Crude RRs are presented because, for comparisons within First Nations and non-First Nations (separately), they were unaffected by adjusting for observed individual-level variables.

P<0.05;

Fig. 1.

Birth Outcomes and Infant Mortality by Neighborhood Socioeconomic Status Indicators among First Nations and non-First Nations in Manitoba, Canada 1991–2000.

Neighborhood Education

For non-First Nations, significantly higher risks of infant death (during the neonatal and especially the postneonatal periods) were observed comparing the lowest neighborhood education quintile with all other neighborhoods, but for First Nations the corresponding differences were smaller and not statistically significant (Table 3, Fig. 1). For both First Nations and non-First Nations, risks of preterm birth were significantly higher in the lowest neighborhood education quintile compared to all other neighborhoods, but a stronger association was observed for non-First Nations.

Neighborhood Unemployment

For both First Nations and non-First Nations, small-for-gestational-age birth and infant death (especially in the postneonatal period) occurred significantly more frequently in the quintile with the highest neighborhood unemployment rates compared to all other neighborhoods (Table 3, Fig. 1). For non-First Nations, a significantly higher risk of preterm birth was observed comparing the highest unemployment neighborhood quintile to all other neighborhoods, but the corresponding risk difference was smaller and not statistically significant for First Nations.

Neighborhood Lone Parents

For non-First Nations, significantly higher risks of preterm birth, small-for-gestational-age, and infant death (especially postneonatal death) were observed in the quintile with the highest percentage of lone parents compared to all other neighborhoods, while all these risk differences were small and not statistically significant for First Nations (Table 3, Fig. 1).

Comparing First Nations to non-First Nations, crude and adjusted ORs showed generally similar patterns of relative risks for adverse birth outcomes (Table 4), except that the disparities with respect to postneonatal death and SIDS became substantially smaller after adjusting for maternal characteristics, and even smaller after further adjusting for the four measures of neighborhood socioeconomic status.

Table 4.

Crude and Adjusted ORs of Birth Outcomes, Infant Death, and Cause-Specific Infant Death comparing First Nations Versus Non-First Nations in Manitoba, 1991–2000

| Outcome | Crude OR (95% CI) | Adjusted OR§ (95% CI) | Adjusted OR# (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Births | |||

| Preterm | 1.13 (1.07, 1.18)* | 1.09 (1.03, 1.15)* | 0.94 (0.89, 1.01) |

| Small for gestational-age | 0.77 (0.74, 0.81)* | 0.70 (0.67, 0.74)* | 0.61 (0.58, 0.65)* |

| Large for gestational-age | 1.70 (1.64, 1.77)* | 1.80 (1.72, 1.87)* | 1.85 (1.77, 1.94)* |

| Deaths | |||

| Infant | 1.95 (1.69, 2.26)* | 1.51 (1.28, 1.78)* | 1.31 (1.10, 1.58)* |

| Neonatal | 1.12 (0.90, 1.40) | 0.99 (0.77, 1.27) | 0.92 (0.70, 1.21) |

| Postneonatal | 3.59 (2.92, 4.41)* | 2.24 (1.77, 2.83)* | 1.79 (1.38, 2.32)* |

| Cause-specific infant death | |||

| Congenital anomalies | 1.67 (1.29, 2.16)* | 1.57 (1.17, 2.11)* | 1.47 (1.05, 2.05)* |

| Immaturity-related | 0.76 (0.49, 1.18) | 0.53 (0.33, 0.85)* | 0.49 (0.29, 0.81)* |

| Neonatal asphyxia | 1.41 (0.74, 2.69) | 1.67 (0.78, 3.57) | 1.71 (0.75, 3.91) |

| Postneonatal SIDS | 4.47 (3.00, 6.67)* | 2.12 (1.35, 3.31)* | 1.64 (1.00, 2.67)* |

P<0.05. OR=odds ratio; CI=confidence interval; SIDS=sudden infant death syndrome.

The adjusted ORs were controlled for individual-level characteristics: infant sex (male, female), maternal age (<20, 20–34, 35+), marital status (married or not), parity (primiparous or not) and multiple pregnancy (singleton or not), plus rural versus urban residence.

The adjusted ORs were controlled for the above-mentioned characteristics plus neighborhood socioeconomic characteristics (lowest status quintile versus all other neighborhoods) with respect to income, education, lone parents, and unemployment. See Methods for details.

DISCUSSION

Main Findings

Our study reveals that low neighborhood socioeconomic status was associated with adverse birth outcomes and infant mortality even among First Nations, but the various measures of neighborhood socioeconomic status sometimes revealed somewhat different risk patterns among First Nations and non-First Nations. Furthermore, our results indicate that low neighborhood socioeconomic status may partly explain the higher infant mortality, and especially the higher post-neonatal mortality, among First Nations in Manitoba. There is a need to deal with the root causes of the generally lower socioeconomic status of Aboriginal people. More and better maternal and infant care programs targeting Aboriginal communities and low socioeconomic status neighborhoods are needed to reduce the high rates of adverse birth outcomes and infant mortality in such vulnerable populations.

Comparisons with Findings from Previous Studies

Many studies have reported higher rates of adverse birth outcomes in neighborhoods of lower socioeconomic status [3,7,15,16]. However, our study may be the first to report on birth outcomes and infant mortality by neighborhood socioeconomic status among an Aboriginal population. It may be argued that First Nations living on reserves (mostly rural) could be less likely to be affected by differences in neighborhood socioeconomic status. However, only about half of all First Nations people in Manitoba live on such reserves, and our neighborhood socioeconomic status quintiles were generated for rural and urban areas separately. Our comparisons clearly show higher rates of adverse birth outcomes and infant mortality in neighborhoods of low socioeconomic status even among First Nations. On the other hand, the higher risks observed in neighborhoods of lower socioeconomic status could partly reflect the effects of unmeasured differences in individual-level socioeconomic status (which were unavailable in our data). The observed effects may reflect the mixed effects of individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status.

The substantially higher risks of infant death, especially postneonatal death, and SIDS in neighborhoods of lower socioeconomic status imply a need for programs to promote better infant care and to address the underlying disparities in social determinants of health such as inadequate housing and poverty. It is clear that First Nations much more likely live in more socio-economically disadvantaged neighborhoods than non-First Nations. The modest reductions in the risk disparities with respect to infant death and especially postneonatal death and SIDS when adjusting for neighborhood socioeconomic status indicate that lower neighborhood socioeconomic status was an important contributor to the excess infant mortality among First Nations. The root causes of the generally lower socioeconomic status of Aboriginal people should be dealt with in any policy developments aimed at reducing adverse birth outcomes and infant mortality among First Nations. The major causes of excess infant deaths among First Nations were congenital anomalies and SIDS. There is a need for more effective infant health promotion programs, in particular the promotion of “back-to-sleep”, maternal smoking cessation and avoidance of exposure to environmental tobacco smoke to reduce SIDS [17,18] in First Nations communities. The substantially high risk of infant death due to congenital anomalies (adjusted OR=1.5) among First Nations deserve further investigations to understand the causes and potential prevention measures.

The less consistent disparities in birth outcomes for First Nations according to the different measures of neighborhood socioeconomic status may partly reflect a potentially different significance of the various dimensions of neighborhood socioeconomic status for First Nations, or residual measurement errors. For First Nations, it appears that neighborhood income and unemployment are more closely linked to infant mortality (especially postneonatal mortality) than are neighborhood education or neighborhood lone parents. In contrast, among non-First Nations, all four dimensions of neighborhood socioeconomic status seem equally important for infant mortality. Non-First Nations had elevated risks of infant death in neighborhoods with a high proportion of lone parents, but this effect was virtually absent for First Nations. The reasons for such differential effects are unclear, though we speculate that they may reflect differences in individual-level risk factor profiles associated with lone parenthood among First Nations and non-First Nations.

Limitations

We did not have data on many potentially confounding risk factors or effect mediators such as maternal smoking, breastfeeding, individual-level education, income, occupation, pregnancy complications, or use of prenatal care. Differences in these unobserved factors may partially explain or mediate the disparities in birth outcomes and infant mortality comparing First Nations to non-First Nations. The observed effects of neighborhood socioeconomic status likely partly reflect the effects of individual-level socioeconomic status. Secondly, we used postal code based geocoding to determine place of residence. This method results in some misclassification of neighborhood socioeconomic status, particularly in rural areas where one postal code typically serves multiple enumeration areas; in such cases the assignment was random but took account of weights based on census population count by postal code and enumeration area. However, such misclassification would only be important if there were large differentials in socioeconomic status between the adjacent neighborhoods, and would tend to reduce the extent of the disparities observed across neighborhoods. Also, some First Nations parents may not have reported their ethnicity on birth registrations, resulting in their misclassification as non-First Nations. Such misclassification would also tend to reduce the extent of the disparities observed between First Nations and non-First Nations.

SYNOPSIS

Low neighborhood socioeconomic status was associated with an elevated risk of infant death among First Nations, and may partly account for their higher rates of infant mortality compared to non-First Nations in Manitoba.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a research grant from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research – Institute of Aboriginal Peoples’ Health (CIHR-IAPH, grant # 73551 – ZC Luo). We are grateful to Statistics Canada for providing access to the data for the research project. F Simonet was supported by a scholarship from the CIHR Strategic Training Initiative in Research in Reproductive Health Science, and S Wassimi by a studentship from the research grant. Dr. Luo was supported by a Clinical Epidemiology Junior Scholar Award from the Fonds de Recherche en Santé du Québec, and a CIHR New Investigator award in Gender and Health, Dr. Heaman by a CIHR Mid-Career Research Chair award in Gender and Health, Dr. Smylie by a CIHR New Investigator award, Dr. Martens by a CIHR/Public Health Agency of Canada Applied Public Health Chair award, and Dr. Fraser by a CIHR Canada Research Chair award in perinatal epidemiology.

References

- 1.Bhutta ZA, Darmstadt GL, Hasan BS, Haws RA. Community-based interventions for improving perinatal and neonatal health outcomes in developing countries: a review of the evidence. Pediatrics. 2005;115 (Suppl 2):519–617. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-1441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Luo ZC, Wilkins R, Platt RW, Kramer MS. Risks of adverse pregnancy outcomes among Inuit and North American Indian women in Quebec, 1985–97. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2004;18(1):40–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2003.00529.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Krieger N, Chen JT, Waterman PD, Soobader MJ, Subramanian SV, Carson R. Choosing area based socioeconomic measures to monitor social inequalities in low birth weight and childhood lead poisoning: The Public Health Disparities Geocoding Project (US) J Epidemiol Comm Health. 2003;57(3):186–99. doi: 10.1136/jech.57.3.186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lekea-Karanika V, Tzoumaka-Bakoula C, Matsaniotis NS. Sociodemographic determinants of low birthweight in Greece: a population study. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1999;13(1):65–77. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.1999.00158.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luo ZC, Kierans WJ, Wilkins R, Liston RM, Mohamed J, Kramer MS. Disparities in birth outcomes by neighborhood income: temporal trends in rural and urban areas, British Columbia. Epidemiol. 2004;15(6):679–86. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000142149.34095.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valero De BJ, Soriano T, Albaladejo R, et al. Risk factors for low birth weight: a review. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2004;116(1):3–15. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2004.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wilkins R, Berthelot JM, Ng E. Trends in mortality by neighbourhood income in urban Canada from 1971 to 1996. Health Reports. 2002;13(Supplement):1–27. Statistics Canada, Catalogue 82–003-SIE. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Winkleby MA, Jatulis DE, Frank E, Fortmann SP. Socioeconomic status and health: how education, income, and occupation contribute to risk factors for cardiovascular disease. Am J Public Health. 1992;82(6):816–20. doi: 10.2105/ajph.82.6.816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fair M, Cyr M, Allen AC, Wen SW, Guyon G, MacDonald RC. An assessment of the validity of a computer system for probabilistic record linkage of birth and infant death records in Canada. The Fetal and Infant Health Study Group. Chronic Dis Can. 2000;21(1):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wilkins R. Automated geographic coding based on the Statistics Canada Postal Code Conversion files, including postal codes to May 2002. Ottawa: Health Analysis and Measurement Group, Statistics Canada; 2002. PCCF+ Version 3J User’s Guide. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics Canada. 1996 Census Dictionary, Final Edition. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 1999. Catalogue no. 92–301E. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Plessis V, Beshiri R, Bollman RD, Clemenson H. Rural and Small Town Canada Analysis Bulletin 2001. Vol. 3. Ottawa: Statistics Canada; 2001. Definitions of rural. Catalogue no. 21–006-XIE. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer MS, Platt RW, Wen SW, et al. A new and improved population-based Canadian reference for birth weight for gestational age. Pediatrics. 2001;108(2):E35. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.2.e35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cole S, Hartford RB, Bergsjo P, McCarthy B. International collaborative effort (ICE) on birth weight, plurality, perinatal, and infant mortality. III: A method of grouping underlying causes of infant death to aid international comparisons. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1989;68(2):113–7. doi: 10.3109/00016348909009897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.O’Campo P, Xue X, Wang MC, Caughy M. Neighborhood risk factors for low birthweight in Baltimore: a multilevel analysis. Am J Public Health. 1997;87(7):1113–8. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.7.1113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pickett KE, Ahern JE, Selvin S, Abrams B. Neighborhood socioeconomic status, maternal race and preterm delivery: a case-control study. Ann Epidemiol. 2002;12(6):410–8. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(01)00249-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fleming P, Blair PS. Sudden Infant Death Syndrome and parental smoking. Early Hum Dev. 2007;83(11):721–5. doi: 10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2007.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blair PS, Sidebotham P, Evason-Coombe C, Edmonds M, Heckstall-Smith EM, Fleming P. Hazardous cosleeping environments and risk factors amenable to change: case-control study of SIDS in south west England. Bri Med J. 2009;339:b3666. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b3666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]