Given wide variation in the implementation of ASCO/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards at US cancer centers, there are significant opportunities for improvement.

Abstract

Purpose:

Because cancer chemotherapy is a high-risk intervention, ASCO and the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) established in 2009 consensus- and evidence-based national standards for the safe administration of chemotherapy. We sought to assess the implementation status of the ASCO/ONS chemotherapy administration safety standards.

Methods:

A written survey of chemotherapy practices was sent to National Cancer Institute–designated cancer centers. Implementation status of each of 31 chemotherapy administration safety standards was self-reported.

Results:

Forty-four (80%) of 55 eligible centers responded. Although the majority of centers have fully implemented at least half of the standards, only four centers reported full implementation of all 31. Implementation varied by standard, with the poorest implementation of standards that addressed documentation of chemotherapy planning, agreed-on intervals for laboratory testing, and patient education and consent before initiation of oral or infusional chemotherapy.

Conclusion:

Given wide variation in the implementation of ASCO/ONS chemotherapy administration safety standards at US cancer centers, there are significant opportunities for improvement.

Introduction

Cancer chemotherapy is a potent but potentially hazardous treatment modality. In the few published studies to date, errors related to chemotherapy administered in ambulatory care occurred at rates of 3% to 8%.1,2 Tragic cases of chemotherapy-related treatment errors figure prominently in newspaper headlines, highlighting the ultimate irony of a life-saving therapy harming the patient it was intended to heal.3–5

To enhance the safety of chemotherapy administration, ASCO and the Oncology Nursing Society (ONS) published in September 2009 a set of adult ambulatory practice standards for the safe administration of chemotherapies used in hematology and oncology practices.6 The ASCO/ONS standards were developed through a structured, multidisciplinary, and consensus-driven process with expert input, literature review, and public comment. The final 31 standards addressed eight specific domains: staffing, chemotherapy planning, general chemotherapy practice, chemotherapy orders, drug preparation, patient consent and education, chemotherapy administration, and monitoring and assessment. The authors urged oncology practices to assess their own implementation of the standards and to consider opportunities to improve on current practices.

The extent to which ambulatory oncology practice conforms to the 2009 ASCO/ONS chemotherapy administration is unknown. Assessing current practice against the standards is a potentially useful indicator of the quality and safety of chemotherapy administration, an opportunity to identify variation in practice across sites of care, and a method for identifying practice areas in need of improvement. Although we acknowledge the applicability of the ASCO/ONS standards to all practice settings, we reasoned that an examination of major US cancer centers would help to establish a baseline of performance in these relatively well-resourced, high-profile organizations. Therefore, we set out to characterize current implementation of the ASCO/ONS standards in National Cancer Institute (NCI) –designated cancer centers.

Methods

Participants

We sought to identify a representative from each of the 66 NCI-designated cancer centers who was familiar with the organization and delivery of chemotherapy in their institution, particularly in ambulatory care. In a previous study,7 we found that pharmacy directors were knowledgeable in this regard and could readily access clinical leaders and front-line staff. Accordingly, we collected contact information for cancer center pharmacy directors from the NCI Web site, cancer center Web sites and telephone operators, and a mailing list of pharmacy directors. We excluded seven centers that conduct only laboratory research and do not provide direct patient care, as well as four newly designated centers, yielding 55 eligible institutions.

Instrument Development

We developed a written survey that presented each item in the ASCO/ONS chemotherapy administration standards in the same order and eight-section format as the 31 published standards. In most cases, survey items replicated the standards verbatim. Several longer standards were paraphrased to enhance readability and to avoid combining two or more issues in a single item. For example, standard 31 states, “The practice has a process for risk-free reporting of errors or near misses. Error and near-miss reports are reviewed and evaluated at least semiannually.” Because this standard addressed two separate issues (the reporting process itself and review of the reports), we divided it into two separate survey items. We included the full text of the published standards with each survey, and respondents were encouraged to refer to the original document in formulating their responses. We asked respondents to indicate the degree to which the standard was implemented in their own organization. Response options included either a four-level Likert scale to reflect the extent of implementation (always, usually, rarely, never) or binary responses (yes, no) when the standard could only be either present or absent (eg, “All clinical staff maintains current certification in basic life support”). We queried respondents about all component items within each standard. For example, the chemotherapy order form standard (No. 10) comprises 16 items, including the presence of patient identifiers, date, drug, dose, regimen or protocol, cycle, and so forth. In total, the instrument included 99 items about the 31 standards.

Survey Administration

We contacted each pharmacy director by US mail in May 2010. The cover letter explained that the research was intended to benchmark the performance of NCI-designated cancer centers and to identify opportunities for improvement. It promised confidentiality of respondents and their organizations. The letter included the written survey instrument and published standards. We encouraged all primary respondents to confer with their colleagues freely, as the full scope of chemotherapy administration practices was likely to require the knowledge of multiple individuals. We made up to three follow-up telephone calls and sent two e-mail reminders with electronic versions of the survey to nonresponders. We asked those pharmacy directors who were unable to participate to identify alternate respondents from among colleagues with the requisite knowledge of the organizations' chemotherapy administration practices. In 14 cases, the pharmacy director's office referred us to another knowledgeable primary respondent. We collected completed surveys by US mail and fax by the end of August 2010 and entered survey responses into an electronic database for analysis.

Data Analyses

We hypothesized that there would be significant variation among cancer centers in the implementation of the ASCO/ONS chemotherapy administration standards. We also anticipated that performance would be modest overall.

We counted the number of items in each standard to which respondents provided the most positive response options (“yes” or “always”). Because the number of items in each standard varied from one to 16, we defined a standard as fully implemented if more than 90% of responses were in the most positive category, partially implemented if 50% to 90% of responses were in the most positive category, and incompletely implemented if less than 50% of responses were in the most positive category. For example, we classified a cancer center that answered “yes” to five of the six staffing-related items as having partially implemented the staffing-related standard. We adjusted the denominators of these calculations to account for items with missing responses. The percentage of missing values per item ranged from 0% to 39%. Twenty-nine items had complete responses, 39 items lacked a response from one center, and the remaining 31 items lacked responses from two or more centers.

To more easily interpret the results, we repeated this analysis for each of the eight chemotherapy standard domains (eg, staffing-related standards, chemotherapy planning, general chemotherapy practice standards, and so forth). We again defined full, partial, and incomplete implementation on the basis of the number of fully implemented standards within each domain, weighting each standard equally. Internal consistency was generally high among the standards within each domain (Cronbach's alpha8 > 0.7 for six of the eight domains). We then calculated the number and percentage of cancer centers that had implemented each standard (by standard and by domain), and the number and percentage of standards that each center had implemented. We excluded from this analysis a single center that provided insufficient information to assess their performance on the majority of standards.

From publicly available sources, we abstracted information about each cancer center, including geographic region, ownership, teaching status, and organization as a stand-alone cancer center or as a “matrixed” component of a larger medical center. Analyses were performed by using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Carey, NC). This study was approved by the Dana-Farber Harvard Cancer Center institutional review board.

Results

Respondent and Organizational Characteristics

We received completed surveys from 44 of 55 eligible centers, an 80% response rate. Characteristics of the 44 survey respondents and their organizations are shown in Table 1. Although the majority of respondents were pharmacy directors, these primary respondents conferred with 89 other colleagues, including physicians, nurses, pharmacists, and quality improvement specialists. Of the respondent organizations, most were part of a larger medical center. Respondent organizations were evenly distributed geographically.

Table 1.

Respondent and Cancer Center Characteristics

| Characteristic | Participant Organizations (n = 44) |

Nonparticipant Organizations (n = 11) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | %* | No. | %* | |

| Respondents | ||||

| Primary respondent (n = 44) | ||||

| Pharmacy director (executive, director, manager) | 30 | 68 | ||

| Oncology pharmacist/specialist | 7 | 16 | ||

| Safety or operational leader | 4 | 9 | ||

| Not specified | 3 | 7 | ||

| Colleagues with whom primary respondent conferred (N = 89) | ||||

| Pharmacist or pharmacy director | 41 | 46 | ||

| Nurse, nurse practitioner, or nurse manager | 34 | 38 | ||

| Quality or medication safety director | 6 | 7 | ||

| Physician | 4 | 5 | ||

| Other† | 4 | 5 | ||

| Cancer centers | ||||

| Organization | ||||

| Matrix | 35 | 80 | 11 | 100 |

| Stand-alone | 9 | 20 | 0 | 0 |

| Location | ||||

| Northeast | 12 | 27 | 3 | 2 |

| Midwest | 11 | 25 | 2 | 18 |

| South | 9 | 21 | 4 | 36 |

| West | 12 | 27 | 2 | 18 |

| Not-for-profit ownership | 44 | 100 | 11 | 100 |

| Teaching status | 44 | 100 | 11 | 100 |

Percentages may not total 100 as a result of rounding.

Other includes chief medical officer (n = 2), pharmacy and therapeutics committee chair (n = 1), and physician assistant (n = 1).

Implementation of Standards

Implementation of ASCO/ONS chemotherapy administration standards varied considerably by domain (Table 2). More than half of the participating cancer centers fully implemented standards related to chemotherapy administration (31 centers), staffing (30 centers), and drug preparation (25 centers). In contrast, 11 centers had fully implemented standards related to patient consent and education, six had fully implemented standards involving documentation of chemotherapy planning, and only five reported full implementation of general chemotherapy practice standards.

Table 2.

Cancer Center Implementation of ASCO/Oncology Nursing Society Chemotherapy Safety Standards, by Domain

| Domain | Full Implementation |

Partial Implementation |

Incomplete Implementation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |

| Staffing-related standards (one standard, six items) (n = 43) | 30 | 69.8 | 13 | 30.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Chemotherapy planning: chart documentation standards (one standard, eight items) (n = 41) | 6 | 14.6 | 25 | 61.0 | 10 | 24.4 |

| General chemotherapy practice standards (five standards, seven items) (n = 41) | 5 | 12.2 | 18 | 43.9 | 18 | 43.9 |

| Chemotherapy order standards (four standards, 22 items) (n = 44) | 18 | 40.9 | 15 | 34.1 | 11 | 25.0 |

| Drug preparation (three standards, 17 items) (n = 44) | 25 | 56.8 | 18 | 40.9 | 1 | 2.3 |

| Patient consent and education (three standards, 10 items) (n = 42) | 11 | 26.2 | 15 | 35.7 | 16 | 38.1 |

| Chemotherapy administration (three standards, 12 items) (n = 44) | 31 | 70.5 | 13 | 29.6 | 0 | 0 |

| Monitoring and assessment (11 standards, 17 items) (n = 43) | 14 | 32.6 | 21 | 48.8 | 8 | 18.6 |

| Total (31 standards, 99 items) (n = 43) | 8 | 18.6 | 30 | 69.8 | 5 | 11.6 |

Table 3 provides more detailed information about the standards within each domain with the highest and lowest implementation rates. The most widely implemented standards addressed maintenance of protocols for medical emergencies (41 centers), availability of practitioners on site during chemotherapy administration (42 centers), prohibition of verbal orders except to hold or stop chemotherapy (37 centers), and maintenance of a referral list for supportive care services (37 centers). Only six standards were fully implemented in at least 80% of the cancer centers. In each case, the standard addressed a single activity that could be achieved through policy or procedure.

Table 3.

Cancer Center Full Implementation of ASCO/Oncology Nursing Society Chemotherapy Safety Standards, by Standard

| Standard | Domain | No. | % | Standard Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standards that more than 80% of cancer centers fully implemented | ||||

| Standard 21 | Monitoring and assessment | 41 of 42 | 97.6 | Practice maintains protocols for response to life-threatening emergencies, including escalation of patient support beyond basic life support. |

| Standard 20 | Chemotherapy administration | 42 of 44 | 95.5 | A licensed independent practitioner is on site and immediately available during all chemotherapy administration. |

| Standard 8 | Chemotherapy order standards | 37 of 43 | 86.1 | The practice does not allow verbal orders except to hold or stop chemotherapy administration. New orders or changes to orders must be made in writing. |

| Standard 24 | Monitoring and assessment | 37 of 43 | 86.1 | The practice maintains a referral list for psychosocial and other supportive care services. |

| Standard 31 | Monitoring and assessment | 36 of 43 | 83.7 | The practice has a process for risk-free reporting of errors or near misses. Error and near-miss reports are reviewed and evaluated at least semiannually. |

| Standard 19 | Chemotherapy administration | 36 of 44 | 81.8 | Extravasation management procedures are defined; antidote order sets and antidotes are accessible. |

| Standards that less than 50% of cancer centers fully implemented | ||||

| Standard 22 | Monitoring and assessment | 21 of 43 | 48.8 | On each clinical visit during chemotherapy administration, practice staff assess and document in the medical record: changes in clinical status, weight; changes in performance status; allergies, previous reactions, and treatment related toxicities; patient psychosocial concerns and need for support. |

| Standard 10 | Chemotherapy order standards | 20 of 44 | 45.5 | Order forms inclusively list all chemotherapy agents in the regimen and their individual dosing parameters. All medications within the order set are listed using full generic names and follow Joint Commission standards regarding abbreviations. |

| Brand names should be included in orders only where there are multiple products or when including the brand name otherwise assists in identifying a unique drug formulation. | ||||

| Complete orders must include: patient's full name and a second patient identifier; date; diagnosis; regimen name and cycle number; protocol name and number (if applicable); appropriate criteria to treat; allergies; reference to the methodology of the dose calculation or standard practice equations; height, weight, and any other variables used to calculate the dose; dosage; route and rate (if applicable) of administration; schedule; duration; cumulative lifetime dose (if applicable); supportive care treatments appropriate for the regimen; sequence of drug administration (if applicable). | ||||

| Standard 15 | Patient consent and education | 17 of 42 | 40.5 | Before initiation of chemotherapy, each patient is given written documentation, including information regarding his/her diagnosis; goals of therapy; planned duration of chemotherapy, drugs, and schedule; information on possible short-and long-term adverse effects; regimen-or drug-specific risks or symptoms that require notification and emergency contact information; plan for monitoring and follow-up. |

| Standard 17 | Patient consent and education | 16 of 40 | 40.0 | All patients who are prescribed oral chemotherapy are provided written or electronic patient education materials about the oral chemotherapy before or at the time of prescription, including the preparation, administration, and disposal of oral chemotherapy; and family, caregivers, or others based on the patient's ability to assume responsibility for managing therapy. |

| Standard 5 | General chemotherapy practice | 12 of 42 | 28.6 | The practice maintains a written statement that determines the appropriate time interval for regimen-specific laboratory tests that are evidence-based when national guidelines exist, or determined by practitioners at the site. |

| Standard 2 | Chemotherapy planning: chart documentation | 6 of 41 | 14.6 | Chemotherapy planning: chart documentation standards. Prior to prescribing a new chemotherapy regimen, chart documentation available to the prescriber includes: pathological confirmation or verification of initial diagnosis; initial cancer stage or current cancer status; complete medical history and physical examination; presence or absence of allergies and history of hypersensitivity reactions; documentation of patient's comprehension regarding medication regimens, etc.; assessment regarding psychosocial concerns and need for support; the chemotherapy treatment plan; the frequency of office visits and monitoring (for oral chemotherapy). |

In contrast, six standards were fully implemented at fewer than half of the cancer centers. The standards with the lowest implementation rates required provision of treatment-related educational materials to patients before initiating chemotherapy (17 centers), provision of oral chemotherapy–specific educational materials to patients receiving these agents (16 centers), written guidance regarding regimen-specific laboratory testing intervals (12 centers), and chart documentation during chemotherapy planning (six centers). In contrast to the widely implemented standards, these standards generally required a more complex set of actions and assessments. Standard 10, for example, required 20 distinct elements of a complete chemotherapy order. And although most centers addressed most elements of the standard, sites often found it difficult to avoid the use of brand names or to include in an order the patient's cumulative lifetime dose. Similarly, standard 2 required documentation of eight pieces of information before prescribing a new chemotherapy regimen. Although pathologic diagnosis, disease stage, and a medical history and physical examination results were routinely collected, cancer centers were challenged to document patients' understanding of their disease and treatment, an assessment of patients' psychosocial and support needs, a chemotherapy treatment plan, or a plan for monitoring patients receiving oral chemotherapy. The implementation rate for each of the 31 standards is available in Appendix Table A1 (online only).

Variation Among Cancer Centers

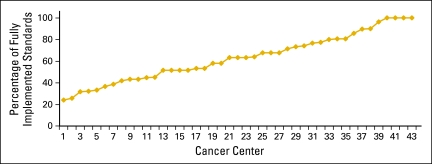

Implementation of the ASCO/ONS standards varied among the cancer centers. Four centers reported full implementation of all 31 standards, whereas most of the remaining centers reported implementation of at least half of the standards. One center had implemented only seven of the standards, and one provided insufficient information to calculate a rate. More detailed information is provided in Appendix Table A2 (online only) and Appendix Figure A1 (online only).

Discussion

In this survey of 44 NCI-designated cancer centers, we found variable implementation of the 2009 ASCO/ONS chemotherapy administration standards. Although the majority of centers have fully implemented at least half, only four centers reported full implementation of all 31 standards. Implementation varied dramatically by standard as well, with poorest implementation of standards that address documentation of chemotherapy planning, agreed-on intervals for laboratory testing, and patient education and consent before initiation of oral or infusional chemotherapy.

The slower adoption of certain standards reflects several challenges, including the complexity of the requirement, its novelty with respect to established practice, and the infrastructure required to support it. For example, the chemotherapy planning standard requires documentation of pathologic confirmation of the diagnosis, cancer staging, a complete medical and medication history, assessment of psychosocial concerns, a chemotherapy treatment plan, and (if appropriate) a plan for monitoring oral chemotherapy. These elements of performance represent a significant amount of work for the clinician to assemble, digest, and record. The development of oncology-specific electronic health record applications may facilitate this practice.9–11 Unfortunately, there are few commercially available applications that address some or all of these issues. Even if such systems were to become available, their implementation might require significant changes in work flow and staffing resources in order to incorporate them into routine practice.

Slow adoption may also reflect a lack of consensus about clinical care in the practice or profession. For example, clinicians within a practice may have different perspectives about the frequency with which regimen-specific laboratory testing is performed. Absent external guidelines, the standards call for a written document at the practice level that recommends consistent care. Creating shared expectations about laboratory monitoring might be difficult in the absence of empirical data that show that one approach is superior to another or that take into account differences among patients. Although the ASCO/ONS standards seek to ensure quality by improving within-practice consistency, clinicians could perceive this approach as a challenge to their autonomy.12

Standards related to patient consent and education emphasize the importance of providing detailed written documentation before therapy, including information about who to call when experiencing treatment-related symptoms. Centers reported limited performance in each of these areas. The standards also address the need to provide educational materials for patients using oral chemotherapy, a novel area of practice involving home administration. Slow adoption of these standards reflects the novelty of this area of practice and the slow development of an infrastructure to support it.13 In a previous study of 42 US cancer centers,7 we found inconsistent prescribing requirements, methods for obtaining informed consent, and procedures for monitoring adherence. Lack of patient education and support might account for the problems with safe handling, adherence, and reporting noted in several recent studies.2,14–16

Variable implementation of the ASCO/ONS chemotherapy safety standards reflects practice across NCI-designated centers and hints at even wider variability in other ambulatory settings where chemotherapy is administered. ASCO and ONS intentionally set a high bar for chemotherapy administration, setting standards that challenge current practice. The standards reflect a mix of evidence- and consensus-based assessments that will require periodic revision on the basis of research, experience, evolving best practice, and emerging risks and vulnerabilities. The increasing use of oral chemotherapy, for example, requires a customized approach to address dosing, handling, and dispensing problems that have recently come to light.

The high degree of implementation, at least in some centers, suggests that the standards are attainable given sufficient attention and resources. This also reflects a growing awareness in the oncology community of the role of standardization as a key strategy for building safe systems. With growth in volume as well as intensity and duration of services, cancer providers will need to embrace “industrial-style” care delivery approaches and solutions while preserving the customized, hands-on care that has long been the hallmark of oncology practice.17–20

Taking the standards as a guide for enhancing the safety of chemotherapy administration, how should cancer centers proceed? We suggest that centers perform a gap analysis of implementation opportunities relative to the standards, identify institution-specific vulnerabilities, and assess the costs and associated benefits of improvement initiatives. ASCO/ONS could facilitate the process by providing centers with guidance regarding prioritization of standards, identifying best practice recommendations, and facilitating improvement initiatives.

This study had several limitations. Although we promised confidentiality to respondents and their organizations, social desirability bias may have led respondents to report more favorable adherence with ASCO/ONS chemotherapy administration standards than an impartial observer would have assigned. Indeed, estimating the typical performance of a complex organization with a variety of practices is in itself a difficult and subjective task. We hoped that this task would be facilitated by eliciting input from cancer center colleagues, and this occurred at most centers. Nonresponse bias might also be present if the performance of the 11 nonparticipating centers differs from that of the participating centers. Like social desirability bias, nonresponse bias would likely overestimate adherence with the standards. Finally, our results reflect the performance of NCI-designated cancer centers. Generalizing these results to other practice settings requires further investigation.

In conclusion, there is variable adherence to recently promulgated chemotherapy administration safety standards among US cancer centers. There are significant opportunities for improvement, particularly with regard to standards that address documentation of chemotherapy planning, agreed-on intervals for laboratory testing, and patient education and consent before initiation of oral or infusional chemotherapy.

Acknowledgment

We thank Lisa Lewis and Daniela Brouillard for their assistance in coordinating the survey described in this study, Audrea Szabatura for her assistance in reaching out to pharmacy directors, and the respondents who generously completed the survey.

Appendix

Table A1.

Cancer Center Implementation of ASCO/Oncology Nursing Society Chemotherapy Safety Standards (full list)

| Standard | Domain | Total No. of Centers | Full Implementation |

Partial Implementation |

Incomplete Implementation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | |||

| 1 | Staffing-related standards | 43 | 30 | 69.8 | 13 | 30.2 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 2 | Chemotherapy planning: chart documentation standards | 41 | 6 | 14.6 | 25 | 61.0 | 10 | 24.4 |

| 3 | General chemotherapy practice standards | 39 | 24 | 61.5 | 7 | 18.0 | 8 | 20.5 |

| 4 | General chemotherapy practice standards | 39 | 20 | 51.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 19 | 48.7 |

| 5 | General chemotherapy practice standards | 42 | 12 | 28.6 | 6 | 14.3 | 24 | 57.1 |

| 6 | General chemotherapy practice standards | 41 | 26 | 63.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 36.6 |

| 7 | General chemotherapy practice standards | 26 | 13 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 50.0 |

| 8 | Chemotherapy order standards | 43 | 37 | 86.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 14.0 |

| 9 | Chemotherapy order standards | 43 | 25 | 58.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 18 | 41.9 |

| 10 | Chemotherapy order standards | 44 | 20 | 45.5 | 24 | 54.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 11 | Chemotherapy order standards | 43 | 29 | 67.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 14 | 32.6 |

| 12 | Drug preparation | 44 | 35 | 79.6 | 8 | 18.2 | 1 | 2.3 |

| 13 | Drug preparation | 44 | 35 | 79.6 | 9 | 20.5 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 14 | Drug preparation | 44 | 28 | 63.6 | 11 | 25.0 | 5 | 11.4 |

| 15 | Patient consent and education | 42 | 17 | 40.5 | 13 | 31.0 | 12 | 28.6 |

| 16 | Patient consent and education | 41 | 26 | 63.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 15 | 36.6 |

| 17 | Patient consent and education | 40 | 16 | 40.0 | 2 | 5.0 | 22 | 55.0 |

| 18 | Chemotherapy administration | 43 | 26 | 60.5 | 16 | 37.2 | 1 | 2.3 |

| 19 | Chemotherapy administration | 44 | 36 | 81.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 8 | 18.2 |

| 20 | Chemotherapy administration | 44 | 42 | 95.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 4.6 |

| 21 | Monitoring and assessment | 42 | 41 | 97.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 2.4 |

| 22 | Monitoring and assessment | 43 | 21 | 48.8 | 15 | 34.9 | 7 | 16.3 |

| 23 | Monitoring and assessment | 43 | 22 | 51.2 | 5 | 11.6 | 16 | 37.2 |

| 24 | Monitoring and assessment | 43 | 37 | 86.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 6 | 14.0 |

| 25 | Monitoring and assessment | 42 | 21 | 50.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 21 | 50.0 |

| 26 | Monitoring and assessment | 43 | 30 | 69.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 13 | 30.2 |

| 27 | Monitoring and assessment | 43 | 25 | 58.1 | 16 | 37.2 | 2 | 4.7 |

| 28 | Monitoring and assessment | 42 | 26 | 61.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 16 | 38.1 |

| 29 | Monitoring and assessment | 43 | 25 | 58.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 18 | 41.9 |

| 30 | Monitoring and assessment | 42 | 31 | 73.8 | 0 | 0.0 | 11 | 26.2 |

| 31 | Monitoring and assessment | 43 | 36 | 83.7 | 4 | 9.3 | 3 | 7.0 |

Table A2.

Cancer Center Implementation of ASCO/Oncology Nursing Society Chemotherapy Safety Standards, by Cancer Center (full list)

| Cancer Center | Total No. of Standards | Full Implementation |

Partial Implementation |

Incomplete Implementation |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | % | No. | % | No. | % | ||

| 1 | 29 | 7 | 24.1 | 4 | 13.8 | 18 | 62.1 |

| 2 | 31 | 8 | 25.8 | 5 | 16.1 | 18 | 58.1 |

| 3 | 22 | 7 | 31.8 | 5 | 22.7 | 10 | 45.5 |

| 4 | 31 | 10 | 32.3 | 4 | 12.9 | 17 | 54.8 |

| 5 | 30 | 10 | 33.3 | 8 | 26.7 | 12 | 40.0 |

| 6 | 30 | 11 | 36.7 | 6 | 20.0 | 13 | 43.3 |

| 7 | 31 | 12 | 38.7 | 8 | 25.8 | 11 | 35.5 |

| 8 | 31 | 13 | 41.9 | 4 | 12.9 | 14 | 45.2 |

| 9 | 30 | 13 | 43.3 | 6 | 20.0 | 11 | 36.7 |

| 10 | 30 | 13 | 43.3 | 6 | 20.0 | 11 | 36.7 |

| 11 | 29 | 13 | 44.8 | 3 | 10.3 | 13 | 44.8 |

| 12 | 31 | 14 | 45.2 | 5 | 16.1 | 12 | 38.7 |

| 13 | 31 | 16 | 51.6 | 5 | 16.1 | 10 | 32.3 |

| 14 | 31 | 16 | 51.6 | 5 | 16.1 | 10 | 32.3 |

| 15 | 31 | 16 | 51.6 | 7 | 22.6 | 8 | 25.8 |

| 16 | 31 | 16 | 51.6 | 7 | 22.6 | 8 | 25.8 |

| 17 | 30 | 16 | 53.3 | 6 | 20.0 | 8 | 26.7 |

| 18 | 30 | 16 | 53.3 | 5 | 16.7 | 9 | 30.0 |

| 19 | 31 | 18 | 58.1 | 3 | 9.7 | 10 | 32.3 |

| 20 | 31 | 18 | 58.1 | 7 | 22.6 | 6 | 19.4 |

| 21 | 30 | 19 | 63.3 | 5 | 16.7 | 6 | 20.0 |

| 22 | 30 | 19 | 63.3 | 5 | 16.7 | 6 | 20.0 |

| 23 | 30 | 19 | 63.3 | 5 | 16.7 | 6 | 20.0 |

| 24 | 25 | 16 | 64.0 | 3 | 12.0 | 6 | 24.0 |

| 25 | 31 | 21 | 67.7 | 1 | 3.2 | 9 | 29.0 |

| 26 | 31 | 21 | 67.7 | 4 | 12.9 | 6 | 19.4 |

| 27 | 31 | 21 | 67.7 | 4 | 12.9 | 6 | 19.4 |

| 28 | 28 | 20 | 71.4 | 4 | 14.3 | 4 | 14.3 |

| 29 | 30 | 22 | 73.3 | 2 | 6.7 | 6 | 20.0 |

| 30 | 31 | 23 | 74.2 | 4 | 12.9 | 4 | 12.9 |

| 31 | 30 | 23 | 76.7 | 4 | 13.3 | 3 | 10.0 |

| 32 | 31 | 24 | 77.4 | 4 | 12.9 | 3 | 9.7 |

| 33 | 30 | 24 | 80.0 | 4 | 13.3 | 2 | 6.7 |

| 34 | 31 | 25 | 80.6 | 2 | 6.5 | 4 | 12.9 |

| 35 | 31 | 25 | 80.6 | 5 | 16.1 | 1 | 3.2 |

| 36 | 28 | 24 | 85.7 | 3 | 10.7 | 1 | 3.6 |

| 37 | 29 | 26 | 89.7 | 3 | 10.3 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 38 | 30 | 27 | 90.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 3 | 10.0 |

| 39 | 27 | 26 | 96.3 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.7 |

| 40 | 30 | 30 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 41 | 31 | 31 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 42 | 31 | 31 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| 43 | 31 | 31 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Figure A1.

Cancer center implementation of ASCO/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards, by cancer center.

Authors' Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

Author Contributions

Conception and design: Saul N. Weingart, Sherri O. Stuver, Michael J. Hassett

Financial support: Saul N. Weingart, Lawrence N. Shulman

Administrative support: Saul N. Weingart, Justin W. Li, Laurinda Morway

Provision of study materials or patients: Saul N. Weingart

Collection and assembly of data: Saul N. Weingart, Justin W. Li, Junya Zhu, Laurinda Morway

Data analysis and interpretation: Saul N. Weingart, Justin W. Li, Junya Zhu, Sherri O. Stuver, Lawrence N. Shulman, Michael J. Hassett

Manuscript writing: Saul N. Weingart, Justin W. Li, Junya Zhu

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

References

- 1.Gandhi TK, Bartel SB, Shulman LN, et al. Medication safety in the ambulatory chemotherapy setting. Cancer. 2005;104:2289–2291. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Walsh KE, Dodd KS, Seetharaman K, et al. Medication errors among adults and children with cancer in the outpatient setting. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:891–896. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.18.6072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O'Halloran G. Woman who died was given wrong drugs. The Irish Times. 2008 May 18;4 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Macdonald J. Chemo error kills patient. The Toronto Star. 2006 Sep 1;A02 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rose D. Two cancer patients died after hospital drug mistake. The Times (London) 2007 Aug 3;19 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jacobson JO, Polovich M, McNiff KK, et al. American Society of Clinical Oncology/Oncology Nursing Society chemotherapy administration safety standards. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5469–5475. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weingart SN, Flug J, Brouillard D, et al. Oral chemotherapy safety practices at US cancer centres: Questionnaire survey. BMJ. 2007;334:407–409. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39069.489757.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maxim PS. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1999. Quantitative Research Methods in the Social Sciences. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shulman LN, Miller RS, Ambinder EP, et al. Principles of safe practice using an oncology EHR system for chemotherapy ordering, preparation, and administration, part 1 of 2. J Oncol Pract. 2008;4:203–206. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0847501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shulman LN, Miller RS, Ambinder EP, et al. Principles of safe practice using an oncology EHR system for chemotherapy ordering, preparation, and administration, part 2 of 2. J Oncol Pract. 2008;4:254–257. doi: 10.1200/JOP.0857501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim GR, Chen AR, Arceci RJ, et al. Error reduction in pediatric chemotherapy: Computerized order entry and failure modes and effects analysis. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2006;160:495–498. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.160.5.495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Larson L. Physician autonomy vs. accountability: Making quality standards and medical style mesh. Trustee. 2007;60:14–21. 14-6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weingart SN, Brown E, Bach PB, et al. NCCN Task Force Report: Oral chemotherapy. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2008;6(suppl):S1–S14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Partridge AH, Avorn J, Wong PS, et al. Adherence to therapy with oral antineoplastic agents. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:652–661. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.9.652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weingart SN, Toro J, Spencer J, et al. Medication errors involving oral chemotherapy. Cancer. 2010;116:2455–2464. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Simchowitz B, Shiman L, Spencer J, et al. Perceptions and experiences of patients using oral chemotherapy. Clin J Oncol Nurs. 2010;14:447–453. doi: 10.1188/10.CJON.447-453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fischer DS, Alfano S, Knobf MT, et al. Improving the cancer chemotherapy use process. J Clin Oncol. 1996;14:3148–3155. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1996.14.12.3148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bonnabry P, Cingria L, Ackermann M, et al. Use of a prospective risk analysis method to improve the safety of the cancer chemotherapy process. Int J Qual Health Care. 2006;18:9–16. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzi082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Robinson DL, Heigham M, Clark J. Using failure mode and effects analysis for safe administration of chemotherapy to hospitalized children with cancer. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32:161–166. doi: 10.1016/s1553-7250(06)32021-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Markert A, Thierry V, Kleber M, et al. Chemotherapy safety and severe adverse events in cancer patients: Strategies to efficiently avoid chemotherapy errors in in- and outpatient treatment. Int J Cancer. 2009;124:722–728. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]