Abstract

Secondary metabolism is commonly associated with morphological development in microorganisms, including fungi. We found that veA, a gene previously shown to control the Aspergillus nidulans sexual/asexual developmental ratio in response to light, also controls secondary metabolism. Specifically, veA regulates the expression of genes implicated in the synthesis of the mycotoxin sterigmatocystin and the antibiotic penicillin. veA is necessary for the expression of the transcription factor aflR, which activates the gene cluster that leads to the production of sterigmatocystin. veA is also necessary for penicillin production. Our results indicated that although veA represses the transcription of the isopenicillin synthetase gene ipnA, it is necessary for the expression of acvA, the key gene in the first step of penicillin biosynthesis, encoding the delta-(l-alpha-aminoadipyl)-l-cysteinyl-d-valine synthetase. With respect to the mechanism of veA in directing morphological development, veA has little effect on the expression of the known sexual transcription factors nsdD and steA. However, we found that veA regulates the expression of the asexual transcription factor brlA by modulating the α/β transcript ratio that controls conidiation.

Fungi of the genus Aspergillus are remarkable organisms that readily produce a wide range of natural products, also called secondary metabolites. These compounds are diverse in structure, and in many cases, the benefits the compounds confer on the organism are unknown. However, interest in these compounds is considerable, as some natural products are of medical, industrial, and/or agricultural importance. Some of these products are beneficial to humankind (e.g., antibiotics), whereas others are deleterious (e.g., mycotoxins) (13, 17).

For several years, the fungus Aspergillus nidulans has been used as a model system to investigate secondary metabolism in Aspergillus spp., including the study of mycotoxins. A. nidulans produces the polyketide sterigmatocystin (ST). ST and the aflatoxins (AF), which are related fungal secondary metabolites (29, 30), are among the most toxic, mutagenic, and carcinogenic natural products known (44, 47). The genes responsible for ST biosynthesis are located in a cluster (7). Among these genes, aflR encodes a pathway-specific transcription factor that simultaneously regulates the expression of other genes in the cluster (52). Hicks et al. (25) reported that aflR expression leading to ST biosynthesis is genetically linked with the production of asexual spores (conidia) in A. nidulans through a G-protein signaling pathway (Fig. 1). According to this model, FluG is involved in the synthesis of an unknown diffusible signal molecule that triggers FlbA (a homolog of GTPase-activating protein). FlbA negatively regulates FadA (an α subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein) by stimulating GTP hydrolysis. In its active form, FadA is GTP bound and transduces a growth-supporting signal to unidentified downstream targets. When FlbA represses FadA, it blocks G-protein signaling for growth and triggers initiation of conidiation and ST production. Knowledge of the mechanism by which FluG, FlbA, and FadA regulate conidiation and ST biosynthesis was recently extended by characterization of a cyclic-AMP-dependent protein kinase catalytic subunit, PkaA (43). Overexpression of pkaA inhibits transcription of brlA (a specific transcription factor that activates conidiation [2]) and aflR and, concomitantly, conidiation and mycotoxin production, respectively (43). Interestingly, certain mutations in genes involved in the G-protein signaling pathway also prevent the formation of spherical fruiting sexual bodies called cleistothecia, where the sexual spores, called ascospores, are formed. Specifically, these mutants are dominant activating mutations in fadA and loss-of-function mutations in sfaD (the β subunit of a heterotrimeric G protein [Fig. 1]) (42) and overexpression of pkaA (43). These findings suggest the existence of a genetic link, not only connecting conidiation and secondary metabolism, but also connecting with processes leading to the development of sexual stages in A. nidulans.

FIG. 1.

Proposed model for the FadA (G-protein) signal transduction pathway regulating growth, ST production, and conidiation in A. nidulans. FluG is involved in the synthesis of a small signal molecule participating in the positive regulation of FlbA, a GTPase-activating protein that negatively regulates FadA (the α-subunit of the heterotrimeric G protein), forming a Gα-Gβ-Gγ complex. Active FadA (separated from Gβ-Gγ subunits) positively regulates PkaA, inducing vegetative growth and inhibiting conidiation and ST production. FadA inhibition allows development and secondary metabolism production to occur (25). AflR and BrlA are specific transcription factors activating ST production and conidiation, respectively.

Studies of the molecular mechanism controlling sexual development are very limited. Only a few genes are known to be involved, and their possible roles in regulating secondary metabolism have never been investigated. One example is the velvet gene, veA, which in A. nidulans mediates a developmental light response (50). In A. nidulans strains containing a wild-type allele of the velvet gene (veA+), light reduces and delays cleistothecial formation and the fungus develops asexually, whereas in the dark, fungal development is directed toward the sexual stage, forming cleistothecia. Under conditions inducing sexual development, the veA deletion (ΔveA) strain is unable to develop sexual structures (33), indicating that veA is required for cleistothecium and ascospore formation. However, the molecular mechanism by which veA regulates sexual development is still unknown, as VeA does not present homology with any known protein that could indicate its functionality.

Other genes involved in A. nidulans sexual development include lsdA, phoA, medA, stuA, tubB, nsdD, and steA (9, 16, 21, 34, 35, 39, 48). Among these genes, nsdD and steA encode transcription factors that are required for sexual development (21, 48). The nsdD gene encodes a GATA-type transcription factor (21), whereas the steA gene (48) is a homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae STE12 (38). Deletion of either nsdD or steA results in blockage of sexual development. Whether veA regulation of sexual development is mediated through nsdD and/or steA has not been investigated. As part of our study, we examined nsdD and steA expression in the ΔveA strain and in the wild-type control strain. Since veA regulates not only sexual development but also asexual development in A. nidulans, we also investigated the possible role of veA in controlling the expression of the asexual transcription factor brlA.

In this work, we report a connection between veA and secondary metabolism in A. nidulans. We have found that the A. nidulans ΔveA strain was unable to produce the mycotoxin ST and that such blockage is mediated by a pronounced reduction in or absence of aflR transcription. Concomitant with the effect of veA on ST production, our study revealed broader changes in the secondary-metabolite profile of the A. nidulans ΔveA strain. We examined the possible role of veA in regulating the penicillin (PN) genes. The PN pathway is well characterized in A. nidulans (5). PN production was lower in the ΔveA strain than in the wild-type control strain. Interestingly, we found that although veA negatively regulates the transcription of ipnA, the isopenicillin synthetase gene, veA is necessary for the expression of acvA, the key gene involved in the first step of the PN biosynthetic pathway encoding delta-(l-alpha-aminoadipyl)-l-cysteinyl-d-valine synthetase (6, 41). Therefore, veA is necessary for both ST and PN production. This study contributes to the overall knowledge of the regulatory genes governing the production of secondary metabolites and to the development of control mechanisms for their detrimental and beneficial effects.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fungal strains and growth conditions.

The A. nidulans strains used in this study are listed in Table 1. These strains were inoculated on YGT medium (0.5% [wt/vol] yeast extract, 2% [wt/vol] glucose, and 1 ml of trace element solution per liter of medium [27]), which has been used previously to promote sexual development in A. nidulans (11, 12, 14, 15), unless otherwise indicated. Appropriate supplements corresponding to the auxotrophic markers were added to the medium (27). Agar (15 g/liter) was added to produce solid medium.

TABLE 1.

A. nidulans strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotypea | Source |

|---|---|---|

| FGSC4 | veA+ | FGSCb |

| FGSC33 | biA1 pyroA4 veA1 | FGSC |

| DVAR1 | pabaA1 yA2 ΔargB::trpC trpC801 ΔveA::argB | K.-S. Chae |

| RNKT1 | ΔveA::argB | This study |

| RJH079 | biA1 argB2 alcA(p)::aflR::trpC veA1 | N. P. Keller |

| WIM126 | pabaA1 yA2 veA+ | L. Yager |

| RNKT4 | alcA(p)::aflR::trpC ΔveA::argB | This study |

| RNKT6 | alcA(p)::aflR::trpC veA+ | This study |

The nomenclature ΔveA::argB indicates that veA has been deleted through gene replacement by the selectable marker gene argB.

FGSC, Fungal Genetics Stock Center.

Physiological studies.

The studies of sexual development were performed with the veA+ (FGSC4) and ΔveA (RNKT1) strains. RNKT1 was obtained by meiotic recombination of DVAR1 (provided by Keon-Sang Chae) and FGSC33 (Table 1). Plates containing 30 ml of solid YGT medium were spread with 100 μl of water containing 105 spores. The cultures were incubated at 37°C in the light or in the dark. After 7 days, a 16-mm-diameter core was removed from each spread plate culture and homogenized in water to release the spores. Sexual and asexual spores were counted using a hemacytometer. The number of Hülle cells, which are involved in the formation of the cleistothecial wall (50), was estimated in the same manner. Identical cores were taken to examine cleistothecial production. The cores were spread with 95% ethanol to enhance visualization of cleistothecia. Cleistothecium production was examined under a stereo-zoom microscope. Conidial production was estimated in cultures grown on glucose minimum medium (GMM), commonly used to study conidiation in A. nidulans (12, 13, 25, 43, 52), as well as on YGT medium. As in the case of ascospores, conidia were also counted using a hemacytometer. Colony growth was recorded as the colony diameters in point inoculation cultures on GMM. Experiments were carried out with four replicates.

Mycotoxin analysis.

Four cores (16-mm diameter) from each replicate of veA+ and ΔveA cultures were collected in a 50-ml Falcon tube, and ST was extracted by adding 5 ml of CHCl3 three consecutive times. The extracts were allowed to dry and then resuspended in 500 μl of CHCl3 before 15 μl of each extract was fractionated on a silica gel thin-layer chromatography (TLC) plate using a toluene-ethyl acetate-acetic acid (80:10:10 [vol/vol/vol]) solvent system. The TLC plates were sprayed with aluminum chloride (15% in ethanol) to intensify ST fluorescence upon exposure to long-wave (365-nm) UV light and baked for 10 min at 80°C prior to being viewed. The approximate sensitivity of the assay was 25 ng. ST purchased from Sigma was used as a standard.

PN analysis.

The PN bioassay was performed essentially as described by Brakhage et al. (6), using Bacillus calidolactis C953 (provided by Geoffrey Turner) as a test organism. First, one core (16-mm diameter) from each replicate of veA+ and ΔveA cultures was homogenized and centrifuged at 15,000 × g for 10 min at 4°C. The resultant supernatants were evaporated in a vacuum centrifuge and resuspended in 50 μl of water, and their PN contents were evaluated as follows. Twenty-five milliliters of the B. calidolactis culture (optical density, 1) was added to 250 ml of melted tryptone-soya agar medium, mixed, and poured into four large petri dishes (150-mm diameter). Ten microliters of each extract, as well as commercial PN G (Sigma), at different concentrations (0.1, 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2.5, and 5 μg/ml) was applied to 2-mm-diameter wells and then incubated at 56°C for 24 h to allow bacterial growth and the visualization of inhibition halos. Inhibition halos were clearly detected at the lower standard amount used (1 ng). Additional controls containing penicillinase from Bacillus cereus (5 U per sample; purchased from Sigma) were used to confirm that the antibacterial activity observed was due to the presence of PN. This allowed us to distinguish the antibiotic activity of PN from those of other compounds that could have been produced. Experiments were carried out with four replicates.

mRNA studies.

Five milliliters of melted 0.7% agar-YGT containing 106 conidia of either the veA+ or ΔveA strain was poured on plates containing 25 ml of solid 1.5% agar-YGT and incubated at 37°C during a time course experiment performed in the dark, a condition that induces sexual development. Samples were harvested for RNA extraction 30, 45, and 60 h after inoculation. In order to evaluate the effect of light on fungal differentiation in the ΔveA strain, a similar experiment was carried out in which the veA+ and ΔveA strains were incubated in the light (25 microeinsteins/m2/s) or in the dark. After 60 h, the samples were harvested and processed for mRNA analysis. To determine the effect of overexpressing aflR on ST production in veA+ and ΔveA strains, 100 ml of GMM liquid cultures were inoculated with 108 conidia of the following strains: FGSC4 (veA+), RNKT6 [alcA(p)::aflR veA+], RNKT1 (ΔveA), and RNKT4 [alcA(p)::aflR ΔveA]. RNKT6 and RNKT4 were generated by meiotic recombination of RJH079 (provided by Nancy Keller) with WIN126 and DVAR1, respectively (Table 1). After 14 h of incubation at 37°C, equal amounts of mycelia were harvested by filtration, washed, and transferred to 20-ml cultures of threonine minimum medium (TMM), which induces the alcA promoter. Mycelia for RNA extraction were collected at the 0- and 24-h points after shift into TMM, where the 0 h represents the moment of shift from GMM to TMM.

Total RNA was isolated from mycelia by using Trizol (Invitrogen) as described by the supplier. Approximately 20 μg of total RNA was used for RNA blot analysis. The probes used in the mRNA analysis were brlA, a 4.3-kb SalI fragment from pTA111 (2); aflR, a 1.3-kb EcoRV-XhoI fragment of pAHK25 (7); stcU, a 0.75-kb SstII-SmaI fragment of pRB7 (52); and ipnA, a 1.1-kb HindIII-EcoRI fragment of pUCHH(458) (46). PCR products amplified with the following primer pairs were used as nsdD- and steA-specific probes, respectively: nsdD, 5′-GATATGAATTCGCTGAC-3′ and 5′-TGCTCTTGAATTCCTCC-3′; steA, 5′-TCCACATCTCAGGTACCG-3′ and 5′-TCGCTCCTGAGTGTGAGT-3′. The identities of the nsdD and steA probes were confirmed by sequencing. RNA loading was normalized in each experiment to rRNA, which remains at constant levels. Densitometry data were acquired and analyzed with the NIH Image J version 1.30 program.

RT-PCR.

A. nidulans acvA, encoding the first enzyme of the PN biosynthetic pathway, presents a transcript of 11,313 nucleotides. Detection of such large transcripts by Northern analysis is difficult to achieve. For this reason, reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) was the method of choice to evaluate the presence or absence of acvA expression. The veA+ and ΔveA strains were incubated on YGT medium in the light or in the dark for 60 h. At that time, the samples were harvested and processed for mRNA analysis. Total RNA samples were treated with a DNA-free kit (Ambion), according to the instructions of the supplier, to eliminate possible trace amounts of contaminant genomic DNA. Moloney murine leukemia virus reverse transcriptase (Promega) and random primers (Pharmacia) were used to synthesize the first-strand cDNAs (0.1 μg of RNA per 20-μl reaction mixture). One microliter from the previous reaction was added to the PCR mixture. The acvA primers used were 5′-AGACGGCCCTGGCTACAG-3′ and 5′-GCGAAACAGTTGGCCTGC-3′. The rRNA primers 5′-TTCTGCCCTATCAACT-3′ and 5′-GGCTGAAACTTAAAGGAATTG-3′ (provided by Melvin Duvall) were used as internal controls. PCR results were analyzed by electrophoresis in a 1% agarose gel.

RESULTS

Velvet, or veA, is a major light-dependent regulatory gene governing development in A. nidulans (33, 50). As part of our preliminary studies, we reproduced the results supporting veA involvement in conidiation and cleistothecial formation. After this verification, we further investigated the role of veA in the regulation of transcription factors necessary for sexual and asexual development. Our group also investigated, for the first time, the involvement of veA in regulating secondary metabolism, particularly the role of veA in the synthesis of the mycotoxin ST and the antibiotic PN.

Roles of veA and light in A. nidulans morphological development.

Several parameters, including sexual development, conidiation, and fungal growth, were analyzed to verify the effect of veA deletion on morphological development in A. nidulans. Since light is important in veA regulation of A. nidulans development (50), the study of colony growth, conidiation, cleistothecial formation, and mycotoxin production in veA+ and ΔveA strains was done in white light or in the dark. The colony size of the veA+ strain was slightly larger than that of the ΔveA strain after 7 days of incubation (data not shown; also confirmed by analysis of variance [P < 0.05]). As predicted, the ΔveA strain was unable to form sexual structures either in the light or in the dark. Our culture conditions were slightly different from those used by Kim et al. (33); however, our results were in agreement for dark conditions (light was not assayed by Kim et al.). These data verified that the veA gene is necessary for sexual development. The higher production of ascospores and lower production of conidia in the veA+ strain grown in the dark were also consistent with previous observations (11, 50). In this experiment, we also noted that the veA+ strain produced approximately two-fold more conidia than the ΔveA strain under both light and dark conditions when the fungus was cultured on GMM (data not shown).

Deletion of veA alters the expression of the transcription factors nsdD, steA, and brlA.

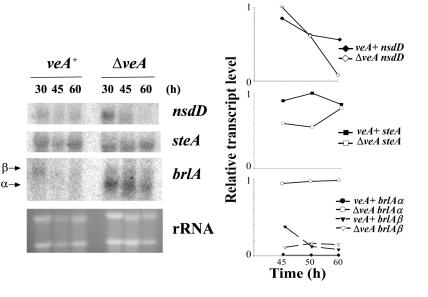

In order to gain further insight into the mechanism through which veA governs morphological differentiation in A. nidulans, in this study we analyzed for the first time the possible role of veA in regulating the expression of key transcription factor genes directing sexual development, such as steA and nsdD, or asexual development, such as brlA. Initially, we investigated whether the blockage in cleistothecial formation was due to an effect of veA deletion on the transcription of the nsdD and/or steA gene, as it is known that inactivation of nsdD or steA expression blocks cleistothecial formation (21, 48). Total RNA was extracted from the veA+ and ΔveA strains after growing them for 30, 45, and 60 h during morphological development (YGT solid cultures) in the dark. The nsdD and steA transcripts were detected in both the veA+ and ΔveA strains (Fig. 2). Deletion of veA had little effect on nsdD and steA expression. The densitometry analysis indicated a decline in nsdD transcription levels at 60 h. At the earliest time point examined (30 h), steA transcription levels were slightly lower than in the wild type (times prior to 30 h were not examined due to the limitation of fungal biomass for analysis), reaching wild-type levels at the 60-h time point (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Effects of the veA deletion on the transcription of genes implicated in morphological development in A. nidulans. The transcriptional patterns of the developmental genes nsdD, steA, and brlA in the veA+ and ΔveA strains were evaluated by Northern analysis. (Left) Total RNAs of the veA+ and ΔveA strains were isolated 30, 45, and 60 h after the strains were cultured on solid YGT medium in the dark. rRNA stained with ethidium bromide is shown to indicate RNA loading. (Right) mRNA was quantitated by densitometry and plotted as relative band intensity normalized to rRNA and to the highest band intensity in each graph (considered as 1 U). Two separate repetitions of these experiments yielded similar results.

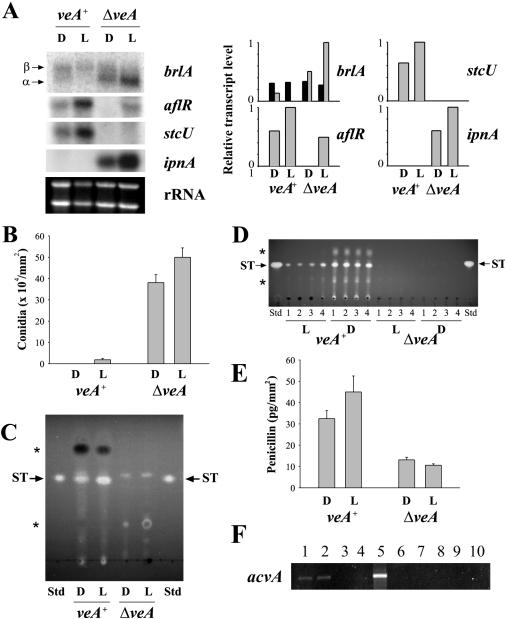

Although the asexual-development transcription factor, brlA, is not required for ST biosynthesis (20), both brlA and the ST transcription factor aflR are coregulated by the fadA signaling pathway genes (Fig. 1) (25). We investigated the possible role of veA in regulating brlA. The brlA gene produces two overlapping transcripts, brlAα and brlAβ (22, 23). brlAβ transcripts were detected in the veA+ and ΔveA strains; however, brlAα was clearly the predominant transcript in the ΔveA strain (Fig. 2), particularly in the ΔveA cultures incubated in the light (Fig. 3A). The increase in brlAα in ΔveA cultures coincided with an increase in conidial production (Fig. 3B). Physiological studies showing that veA also regulates asexual development were previously reported (33, 50); however, this is the first report of the control of veA over the expression of the conidiation-regulatory gene brlA.

FIG. 3.

Combined effects of veA deletion and light on the transcription of genes implicated in morphological and chemical differentiation in A. nidulans. (A) The expression of genes involved in conidiation (brlA) and secondary metabolism (aflR, stcU, and ipnA) was evaluated by Northern analysis in the veA+ and ΔveA strains (left). Total RNAs were isolated from the cultures grown on solid YGT medium after 60 h in the light or in the dark. rRNA stained with ethidium bromide is shown to indicate RNA loading. mRNA was quantitated by densitometry and plotted as relative band intensity normalized to rRNA and to the highest band intensity in each graph (considered as 1 U) (right). Two separate repetitions of these experiments yielded similar results. Under the same experimental conditions, other parameters were analyzed as follows. (B) Conidial production per surface area. The values are means of four replicates. (C) ST analysis by TLC. The uncharacterized compound observed in ΔveA near the ST retention factor (Rf) is not ST (in this assay, ST fluoresces bright yellow while the unknown compound fluoresced blue). (D) ST analysis of samples extracted from GMM cultures by TLC. The uncharacterized compound observed in ΔveA near the ST Rf is not ST (in this assay, ST fluoresces bright yellow while the unknown compound fluoresced blue). (E) Effects of the veA deletion on PN production in A. nidulans on solid YGT medium in the light or in the dark. The values are means of four replicates. (F) Detection of acvA expression on YGT medium by RT-PCR. Lanes: 1, veA+ in the dark; 2, veA+ in the light; 3, ΔveA in the dark; 4, ΔveA in the light; 5, positive control containing genomic DNA as a template; 6, negative control without DNA template; 7 to 10, PCR results of RNA samples (veA+ in the dark, veA+ in the light, ΔveA in the dark, and ΔveA in the light, respectively) before RT, showing the absence of contaminant genomic DNA in the samples. L, light; D, dark; Std, standard; *, other uncharacterized metabolites absent or present in different amounts in ΔveA with respect to veA+. The error bars indicate standard error.

Deletion of veA and light affects ST biosynthesis in A. nidulans.

The possible role of veA in regulating secondary metabolism has never been investigated, and therefore the implications that veA could have for the production of mycotoxin and other secondary metabolites remain unknown. We studied the effect of veA deletion on ST production in cultures in the dark and in the light by TLC. As shown in Fig. 3C and D, the A. nidulans veA+ strain produced the mycotoxin ST, while the ΔveA strain failed to produce ST in both light and dark cultures on YGT and GMM media. This result was also confirmed by liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (data not shown). In the A. nidulans veA+ strain, illumination had an effect on ST biosynthesis that was medium dependent. Nutritional factors can affect not only development but also mycotoxin production. For example, it has been established that certain carbon and nitrogen sources stimulate (i.e., glucose [1, 49]) or inhibit (i.e., nitrate [4, 26]) AF biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus and Aspergillus flavus. Less is known about carbon and nitrogen effects on ST production in A. nidulans. As in the case of AF in A. parasiticus and A. flavus, glucose does not repress but sustains ST production in A. nidulans (8, 25, 31, 43). As for the nitrogen source, Feng and Leonard (18) reported that nitrate GMM supports gene expression for ST biosynthesis in A. nidulans while ammonium GMM does not, showing a transcript expression pattern opposite to that of AF. On the other hand, expression of ST genes and ST production has been shown in ammonium complete medium (containing yeast extract) by Keller et al. (31). Therefore the nitrate-ammonium effect on ST production seems to interact with other medium components, and possibly with other environmental factors. In our experiments, we looked at the effect of light on ST production on two different media. In the veA+ strain, more ST was produced in cultures growing on YGT (medium containing yeast extract) in the light than in the dark (Fig. 3C), whereas more ST production was observed in the dark when the fungus was grown on GMM (containing nitrate) (Fig. 3D). The higher ST production in the light on YGT medium coincides with higher levels of aflR and stcU (one of the enzymatic genes in the ST cluster used as an indicator of cluster activation by aflR) mRNAs in light cultures on YGT (Fig. 3A).

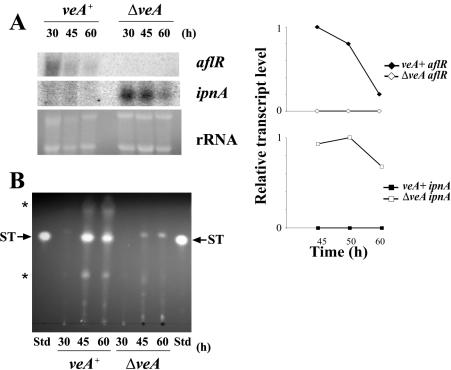

Deletion of veA represses transcription of the ST-specific regulatory gene, aflR.

Our mRNA analysis showed that aflR transcript accumulation was notably lower in the ΔveA strain than the normal aflR transcript levels observed in the wild-type strain under the same experimental conditions (Fig. 3A and 4A). Inactivation of aflR expression is known to block ST biosynthesis (10). ST production was also evaluated in ΔveA and wild-type strains by TLC during a time course experiment (Fig. 4B). The ΔveA strain produced no ST, while ST production was detected at 45 and 60 h in the veA+ strain (Fig. 4B). Although aflR was detected at 60 h in the light cultures in the the ΔveA strain (the aflR transcription level was still lower than that of the wild type under the same experimental conditions [Fig. 3A]), stcU expression was completely absent (Fig. 3A).

FIG. 4.

Effects of veA deletion on transcription of genes implicated in production of secondary metabolites during morphological development in A. nidulans. (A) Transcriptional patterns of genes involved in secondary metabolism, aflR and ipnA, were evaluated by Northern analysis in the veA+ and ΔveA strains. Total RNAs of the veA+ and ΔveA strains were isolated 30, 45, and 60 h after inoculation on solid YGT medium (left). rRNA stained with ethidium bromide is shown to indicate RNA loading. mRNA was quantitated by densitometry and plotted as relative band intensity normalized to rRNA and to the highest band intensity in each graph (considered as 1 U) (right). Two separate repetitions of these experiments yielded similar results. (B) ST analysis by TLC. The uncharacterized compound observed in ΔveA near the ST Rf is not ST (in this assay, ST fluoresces bright yellow while the unknown compound fluoresced blue). Std, standard; *, other uncharacterized metabolites absent or present in different amounts in ΔveA with respect to veA+.

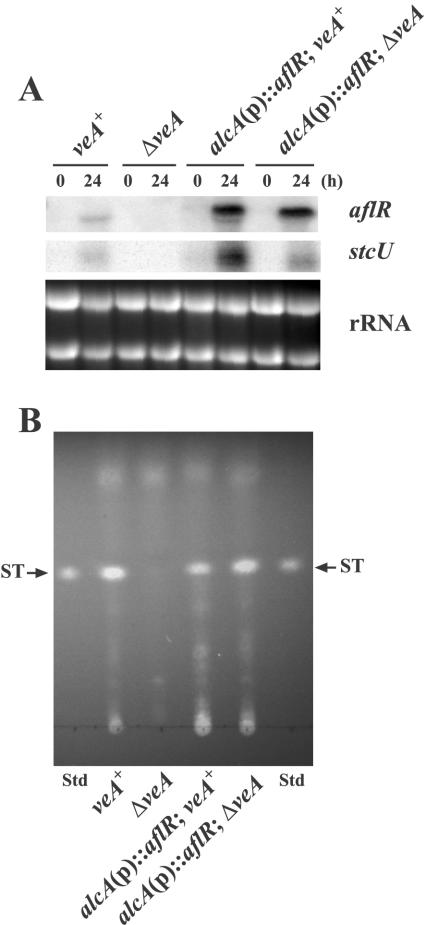

Overexpression of aflR remediates the defect in ST production caused by veA deletion.

Since veA deletion results in a drastic reduction or absence of aflR transcription, and consequently an absence of ST production, we tested the effect of the forced expression of aflR on ST production in the ΔveA background. We generated isogenic alcA(p)::aflR strains differing only in the presence or absence of veA and cultivated them in liquid GMM followed by transfer to TMM, inducing conditions for the alcA promoter. Neither aflR nor stcU was detected in the ΔveA strain without the alcA(p)::aflR fusion, resulting in no ST production (Fig. 5). As expected, high aflR transcript accumulation was detected in both alcA(p)::aflR strains 24 h after the shift into TMM. Under these conditions, stcU expression was partially restored in the ΔveA strain by the overexpression of aflR, leading to ST production.

FIG. 5.

Effects of the overexpression of aflR on ST biosynthesis in the A. nidulans veA+ and ΔveA strains. (A) The expression of aflR and stcU in FGSC4 (veA+), RNKT1 (ΔveA), RNKT6 [alcA(p)::aflR veA+], and RNKT4 [alcA(p)::aflR ΔveA] strains was evaluated by mRNA analysis. Expression of the alcA(p)::aflR construct results in an aflR functional transcript slightly larger than the endogenous transcript (24). Total RNA was isolated from the cultures at zero h and 24 h after transfer from liquid GMM into liquid TMM. rRNA stained with ethidium bromide is shown to indicate RNA loading. (B) ST analysis by TLC. The uncharacterized compound observed in ΔveA near the ST Rf is not ST (in this assay, ST fluoresces bright yellow while the unknown compound fluoresced blue). Std, standard.

Deletion of veA alters the expression of the PN biosynthetic genes ipnA and acvA in A. nidulans.

The TLC analysis of the veA+ and ΔveA strains also indicated a different profile with respect to other metabolites (Fig. 3C and D and 4B), suggesting that veA could have a broader effect, perhaps over additional metabolic pathways. For this reason, we looked at the possible effect of veA deletion on PN biosynthesis at the transcriptional level; specifically, we first examined the expression of ipnA. The ipnA gene encodes an isopenicillin N synthetase, an enzyme required for PN biosynthesis. In contrast to the effect observed on aflR and stcU expression, the ipnA transcripts were abundant in the ΔveA strain (Fig. 3A and 4A). PN production was analyzed by using a bioassay method with B. calidolactis as the test organism. Surprisingly, the veA deletion produced less PN than the veA+ strain (Fig. 3E). For this reason, we also looked at the expression of the gene involved in the first step of the PN biosynthesis pathway, acvA, in the veA+ and ΔveA strains cultured in the light and in the dark. Because of the large size of the acvA transcript (11,313 nucleotides), we chose RT-PCR for its analysis. Our RT-PCR indicated that acvA transcripts were detected only in the veA+ strain, in both light and dark cultures (Fig. 3F) (the rRNA control generated similar amounts of PCR products in all veA+ and ΔveA samples [data not shown]).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we discovered a genetic connection between sexual development and secondary metabolism in A. nidulans mediated by the regulatory gene veA. Our most interesting finding is the control of veA over the expression of genes leading to the production of two different secondary metabolites, the mycotoxin ST and the antibiotic PN. Deletion of veA repressed transcription of the ST-specific transcription factor aflR, and consequently ST gene expression (Fig. 3A, 4A, and 5A), indicating that veA is required for normal aflR expression and ST biosynthesis. On the other hand, deletion of veA enhanced levels of ipnA mRNA (Fig. 3A and 4A), an enzymatic gene in the PN gene cluster. The opposite regulation of ST and PN production has been described for the G-protein α-subunit FadA (45). A. nidulans strains containing the dominant activating allele, fadAG42R, also lost ST gene expression and showed an increase in ipnA expression that led to greater levels of PN biosynthesis. In contrast, the higher ipnA expression found in the veA deletion in our studies did not result in an increase but in a reduction of PN production (Fig. 3E), indicating that although veA is a repressor of ipnA, the ipnA expression level has little effect on PN production. Consequently, these results are in line with those of Fernández-Cañón and Peñalva (19), in which overexpression of ipnA increased isopenicillin N synthetase activity 40-fold yet resulted in only a modest increase in PN production. Subsequently, Kennedy and Turner (32) demonstrated that the expression of acvA, another gene in the PN cluster encoding δ-(l-α-aminoadipyl)-l-cysteinyl-d-valine synthetase, is the rate-limiting step in PN biosynthesis. Furthermore, a reduction in ipnA caused by deletion of the hapC gene (which encodes a component of the wide-domain-regulatory CCAAT-binding complex AnCF/AnCP/PENR1 [28, 37, 40]) resulted in only a moderate reduction in PN, since acvA expression was only slightly affected by the deletion (37). Our results showed a correlation between acvA expression levels and the bioassay results (Fig. 3E and F), supporting acvA (not ipnA) as the limiting step in PN biosynthesis.

Varying the production of secondary metabolites such as ST and PN is a logical strategy by organisms to adapt to their changing environments. One of the environmental factors is light. In A. nidulans, veA has been shown to mediate a light-dependent developmental response (50). Furthermore, results reported by Yager et al. suggest a genetic interaction between veA and fluG, a gene linking development and ST production that, according to these authors, could be a light photoreceptor (51). For this reason we examined the possible effect of light on secondary metabolism in the veA+ strain. Greater accumulation of aflR and stcU transcripts, and consequently higher production of ST, was observed in the A. nidulans wild-type strain incubated in the light than in the same strain incubated in the dark when the fungus was grown on the rich YGT medium (Fig. 3A and C). Higher levels of ST in the light than in the dark were also found when the fungus was growing on another rich medium containing yeast extract called YES (1% sucrose, 2% yeast extract [20]). Interestingly, we found that when the fungus was cultured on the synthetic medium GMM (Fig. 3D), ST production was higher in dark cultures than in those exposed to light. These findings suggest that the effect of light on ST biosynthesis is the result of a complex interaction with other factors, such as the abundance and type of nutrients (i.e., carbon and nitrogen sources) available in the environment. Although light stimulated aflR expression in the absence of veA (to levels still lower than in the veA+ strain in the light), stcU expression was not detected (Fig. 3A), suggesting a possible additional role for veA in regulating aflR at a posttranscriptional level or perhaps affecting additional genetic elements that could affect ST cluster activation. Consistent with these hypotheses, we found that although forced expression of aflR was able to restore stcU expression and ST production in the ΔveA genetic background (Fig. 5), stcU transcript accumulation was still lower than those achieved by aflR overexpression in the veA+ background (Fig. 5A). Shimizu and Keller (43) showed that aflR is negatively regulated at both the transcriptional and posttranscriptional levels by the cyclic-AMP-dependent kinase PkaA, one of the components of the FadA G-protein signaling pathway regulating ST biosynthesis and morphological development (Fig. 1) (25, 43). Whether the role of veA in regulating aflR is connected with the PkaA-mediated mechanism is still unknown but is being investigated as part of our current studies.

Our results indicate that veA constitutes a genetic link between secondary metabolism and morphological development in A. nidulans. As previously mentioned, it is known that light influences fungal development in a response mediated by VeA. Specifically, in A. nidulans strains with a veA wild-type allele (veA+), light decreases and delays cleistothecial formation and the fungus mainly produces conidia, whereas in the absence of light, fungal development is directed toward the sexual stage (50). ΔveA had a mild effect on colony growth, and therefore it is likely that the morphological phenotype observed is not a consequence of a pleiotrophic effect caused by deficient growth. As we confirmed, even under conditions inducing sexual development, ΔveA is unable to form any type of sexual structure: Hülle cells, cleistothecia, or ascospores (data not shown and reference 33), verifying that veA is indeed required for the sexual stage in this fungus. However, the mechanism by which veA regulates cleistothecial production is unknown. This is due in part to the fact that veA is constitutively expressed (33) and its gene product does not present homology with any other protein of characterized function that could indicate a possible mechanism of action for veA. We carried out mRNA analysis to investigate whether the effect of veA on the sexual stage is mediated by the transcription factors nsdD and steA, which are required for normal sexual development in A. nidulans (21, 48). The expression levels of the nsdD and steA genes were similar in the veA+ and ΔveA strains; only slight variations were observed (Fig. 2). It is likely that the moderate differences in the expression levels of these transcription factor genes in the ΔveA strain with respect to the wild type might not be responsible for its complete absence of a sexual stage. Alternatively, whether veA could affect nsdD and steA posttranscriptionally or affect the sexual stage through an nsdD- and steA-independent mechanism is unknown. However, we do know that sexual development and ST production are coregulated by veA at a step previous to the nsdD regulation point, since the ΔnsdD strain produced wild-type levels of ST (data not shown). The case of nsdD in the sexual development-ST relationship is similar to that of brlA in the conidiation-ST relationship. Although brlA deletion prevents conidiation (2), the deletion does not affect ST production (20). Nevertheless, it is known that conidiation and ST production are genetically linked by the FadA signaling pathway at a point preceding brlA (Fig. 1) (25).

In addition to the veA roles discussed above, veA has also been postulated to inhibit conidiation (3, 42, 50). We found that the role of veA in conidiation is medium dependent. While the production of conidia decreased twofold in the ΔveA strain with respect to the control when the strains were grown on GMM (data not shown), conidial production by the ΔveA strain was higher than in the wild type when the strains were grown on YGT medium (∼3,000-fold higher in the dark and 30-fold higher in the light [Fig. 3B]). The higher conidial production in the ΔveA strain on YGT (our results) coincides with results on complete medium (33). However, the possible role of veA in controlling the transcription of conidiation-regulatory genes has not been investigated. Our experiments showed that the increase in conidiation in the ΔveA strain on YGT medium was mediated by an alteration of brlA expression. brlA generates two types of transcripts called brlAα and brlAβ, and its expression is subject to complex regulation at the transcriptional and translational levels (22, 23). There are two open reading frames (ORFs) in the brlAβ transcript; one of them is a small ORF called μORF found upstream of the BrlA coding region. According to Han and Adams (22), translation of μORF inhibits the translation of the second and larger brlAβ ORF (BrlA). The translation of this larger brlAβ ORF is necessary for brlAα transcription. The transcription of brlAα causes the activation of a series of genes that lead to conidiation. In our experiments, brlAβ was detected in the veA+ and ΔveA strains (Fig. 2 and 3A). However, most of the brlA transcript was α type in the ΔveA strain (Fig. 2 and 3A), particularly when exposed to light (Fig. 3A). The fact that brlAα is more abundant in the light in the ΔveA strain coincides with higher conidial production under these conditions (Fig. 3B). Consequently, our data indicate that the deletion of veA affects the α/β brlA transcript ratio. Several possibilities emerge as to how this regulation takes place: (i) veA is required for the translation of μORF, which inhibits brlAβ translation; (ii) veA might negatively regulate brlAβ translation; or (iii) veA might negatively regulate brlAα transcription. Further investigation is needed to elucidate which of these alternatives is correct. In addition, the increase in brlAα transcription in the light in the ΔveA strain suggests the existence of other light-responsive genetic factors controlling brlA expression.

In conclusion, the results of this study indicate that veA is a global regulator controlling both morphological development and secondary metabolism. A veA homolog in A. parasiticus, a producer of the carcinogenic mycotoxin AF, has been identified (A. M. Calvo, J.-W. Bok, W. Brooks, and N. P. Keller, submitted for publication). The observation that deletion of veA suppresses the production of ST without increasing antibiotic production in A. nidulans could be important from an applied perspective as a control strategy for AF because it would avoid the risk of enhancing antibiotic resistance in bacteria in the food chain (36, 45). We have also found veA homologs in A. fumigatus (http://www.tigr.org/tdb/e2k1/afu1) and in other fungal genera, including several mycotoxin-producing Fusarium spp., in Neurospora crassa (http://www.genome.wi.mit.edu/annotation/fungi/neurospora), and in Magnaporthe grisea (http://www.genome.wi.mit.edu/annotation/fungi/magnaporthe). Therefore, the widespread distribution of veA possibly indicates that this important regulator is conserved across fungal genera. These studies contribute to the understanding of the regulatory networks that control fungal development and the production of secondary metabolites. This knowledge will be useful in reducing the detrimental effects of these natural products and in enhancing the production of secondary metabolites that are beneficial.

Acknowledgments

We thank Stuart Hill for critical reading of the manuscript, Keon-Sang Chae for providing us with the fungal strain DVAR1, Nancy Keller for the fungal strain RJH079, Geoffrey Turner for B. calidolactis C953, Melvin Duvall for the rRNA primers, and Elizabeth Gaillard for technical support in the liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry analysis of ST. This study was financed by Northern Illinois University and the Plant Molecular Biology Center at that university.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abdollahi, A., and R. L. Buchanan. 1981. Regulation of aflatoxin biosynthesis: characterization of glucose as an apparent inducer of aflatoxin production. J. Food Sci. 46:143-146. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Adams, T. H., M. T. Boylan, and W. E. Timberlake. 1988. brlA is necessary and sufficient to direct conidiophore development in Aspergillus nidulans. Cell 54:353-362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Adams, T. H., J. K. Wieser, and J. H. Yu. 1998. Asexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:35-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bennett, J. W., P. L. Rubin, L. S. Lee, and P. N. Chen. 1979. Influence of trace elements and nitrogen sources on versicolorin production by mutant strains of Aspergillus parasiticus. Mycopathologia 69:161-166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brakhage, A. A. 1998. Molecular regulation of β-lactam biosynthesis in filamentous fungi. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 62:547-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brakhage, A. A., P. Browne, and G. Turner. 1992. Regulation of Aspergillus nidulans penicillin biosynthesis and penicillin biosynthesis genes acvA and ipnA by glucose. J. Bacteriol. 174:3789-3799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown, D. W., J. H. Yu, H. S. Kelkar, M. Fernandes, T. C. Nesbitt, N. P. Keller, T. H. Adams, and T. J. Leonard. 1996. Twenty-five coregulated transcripts define a sterigmatocystin gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 93:1418-1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Burow, G. B., T. C. Nesbitt, J. Dunlap, and N. P. Keller. 1997. Seed lipoxygenase products modulate Aspergillus mycotoxin biosynthesis. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 10:380-387. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bussink, H. J., and S. A. Osmani. 1998. A cyclin-dependent kinase family member (PHOA) is required to link developmental fate to environmental conditions in Aspergillus nidulans. EMBO J. 17:3990-4003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Butchko, R. A., T. H. Adams, and N. P. Keller. 1999. Aspergillus nidulans mutants defective in stc gene cluster regulation. Genetics 153:715-720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Calvo, A. M., H. W. Gardner, and N. P. Keller. 2001. Genetic connection between fatty acid metabolism and sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Biol. Chem. 276:25766-25774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Calvo, A. M., L. L. Hinze, H. W. Gardner, and N. P. Keller. 1999. Sporogenic effect of polyunsaturated fatty acids on development of Aspergillus spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65:3668-3673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calvo, A. M., R. A. Wilson, J. W. Bok, and N. P. Keller. 2002. Relationship between secondary metabolism and fungal development. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 66:447-459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Champe, S. P., and A. A. el-Zayat. 1989. Isolation of a sexual sporulation hormone from Aspergillus nidulans. J. Bacteriol. 171:3982-3988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Champe, S. P., P. Rao, and A. Chang. 1987. An endogenous inducer of sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. J. Gen. Microbiol. 133:1383-1387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clutterbuck, A. J. 1969. A mutational analysis of conidial development in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 63:317-327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Demain, A. L., and A. Fang. 2000. The natural functions of secondary metabolites. Adv. Biochem. Eng. Biotechnol. 69:1-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feng, G. H., and T. J. Leonard. 1998. Culture conditions control expression of the genes for aflatoxin and sterigmatocystin biosynthesis in Aspergillus parasiticus and Aspergillus nidulans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 64:2275-2277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fernández-Cañón, J. M., and M. A. Peñalva. 1995. Overexpression of two penicillin structural genes in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 246:110-118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guzman-de-Pena, D., J. Aguirre, and J. Ruiz-Herrera. 1998. Correlation between the regulation of sterigmatocystin biosynthesis and asexual and sexual sporulation in Emericella nidulans. Antonie Leeuwenhoek 73:199-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han, K. H., K. Y. Han, J. H. Yu, K. S. Chae, K. Y. Jahng, and D. M. Han. 2001. The nsdD gene encodes a putative GATA-type transcription factor necessary for sexual development of Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Microbiol. 41:299-309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Han, S., and T. H. Adams. 2001. Complex control of the developmental regulatory locus brlA in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Genet. Genomics 266:260-270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Han, S., J. Navarro, R. A. Greve, and T. H. Adams. 1993. Translational repression of brlA expression prevents premature development in Aspergillus. EMBO J. 12:2449-2457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hicks, J., R. A. Lockington, J. Strauss, D. Dieringer, C. P. Kubicek, J. Kelly, and N. P. Keller. 2001. RcoA has pleiotropic effects on Aspergillus nidulans cellular development. Mol. Microbiol. 39:1482-1493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hicks, J. K., J. H. Yu, N. P. Keller, and T. H. Adams. 1997. Aspergillus sporulation and mycotoxin production both require inactivation of the FadA Gα protein-dependent signaling pathway. EMBO J. 16:4916-4923. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kachholz, T., and A. L. Demain. 1983. Nitrate repression of averufin and aflatoxin biosynthesis. J. Nat. Prod. 46:499-506. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Käfer, E. 1977. Meiotic and mitotic recombination in Aspergillus and its chromosomal aberrations. Adv. Genet. 19:33-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kato, M., A. Aoyama, F. Naruse, Y. Tateyama, K. Hayashi, M. Miyazaki, P. Papagiannopoulos, M. A. Davis, M. J. Hynes, T. Kobayashi, and N. Tsukagoshi. 1998. The Aspergillus nidulans CCAAT-binding factor AnCP/AnCF is a heteromeric protein analogous to the HAP complex of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Gen. Genet. 257:404-411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Keller, N. P., and T. H. Adams. 1995. Analysis of a mycotoxin gene cluster in Aspergillus nidulans. SAAS Bull. Biochem. Biotechnol. 8:14-21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keller, N. P., and T. M. Hohn. 1996. Metabolic pathway gene clusters in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 21:17-29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keller, N. P., C. Nesbitt, B. Sarr, T. D. Phillips, and G. B. Burow. 1997. pH regulation of sterigmatocystin and aflatoxin biosynthesis in Aspergillus spp. Phytopathlogy 87:643-648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kennedy, J., and G. Turner. 1996. δ-(l-α-aminoadipyl)-l-cysteinyl-d-valine synthetase is a rate limiting enzyme for penicillin production in Aspergillus nidulans. Mol. Gen. Genet. 253:189-197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim, H., K. Han, K. Kim, D. Han, K. Jahng, and K. Chae. 2002. The veA gene activates sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Fungal Genet. Biol. 37:72-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kirk, K. E., and N. R. Morris. 1991. The tubB α-tubulin gene is essential for sexual development in Aspergillus nidulans. Genes Dev. 5:2014-2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lee, D. W., S. Kim, S. J. Kim, D. M. Han, K. Y. Jahng, and K. S. Chae. 2001. The lsdA gene is necessary for sexual development inhibition by a salt in Aspergillus nidulans. Curr. Genet. 39:237-243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levy, S. B. 1998. The challenge of antibiotic resistance. Sci. Am. 278:46-53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Litzka, O., P. Papagiannopolous, M. A. Davis, M. J. Hynes, and A. A. Brakhage. 1998. The penicillin regulator PENR1 of Aspergillus nidulans is a HAP-like transcriptional complex. Eur. J. Biochem. 251:758-767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Madhani, H. D., and G. R. Fink. 1998. The riddle of MAP kinase signaling specificity. Trends Genet. 14:151-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Miller, K. Y., T. M. Toennis, T. H. Adams, and B. L. Miller. 1991. Isolation and transcriptional characterization of a morphological modifier: the Aspergillus nidulans stunted (stuA) gene. Mol. Gen. Genet. 227:285-292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Papagiannopoulos, P., A. Andrianopoulos, J. A. Sharp, M. A. Davis, and M. J. Hynes. 1996. The hapC gene of Aspergillus nidulans is involved in the expression of CCAAT-containing promoters. Mol. Gen. Genet. 251:412-421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramon, D., L. Carramolino, C. Patino, F. Sanchez, and M. A. Penalva. 1987. Cloning and characterization of the isopenicillin N synthetase gene mediating the formation of the β-lactam ring in Aspergillus nidulans. Gene 57:171-181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Rosen, S., J. H. Yu, and T. H. Adams. 1999. The Aspergillus nidulans sfaD gene encodes a G protein β subunit that is required for normal growth and repression of sporulation. EMBO J. 18:5592-5600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimizu, K., and N. P. Keller. 2001. Genetic involvement of a cAMP-dependent protein kinase in a G protein signaling pathway regulating morphological and chemical transitions in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 157:591-600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Sweeney, M. J., and A. D. Dobson. 1999. Molecular biology of mycotoxin biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 175:149-163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tag, A., J. Hicks, G. Garifullina, C. Ake, Jr., T. D. Phillips, M. Beremand, and N. P. Keller. 2000. G-protein signalling mediates differential production of toxic secondary metabolites. Mol. Microbiol. 38:658-665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tilburn, J., S. Sarkar, D. A. Widdick, E. A. Espeso, M. Orejas, J. Mungroo, M. A. Penalva, and H. N. Arst, Jr. 1995. The Aspergillus PacC zinc finger transcription factor mediates regulation of both acid- and alkaline-expressed genes by ambient pH. EMBO J. 14:779-790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Trail, F., N. Mahanti, and J. Linz. 1995. Molecular biology of aflatoxin biosynthesis. Microbiology 141:755-765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Vallim, M. A., K. Y. Miller, and B. L. Miller. 2000. Aspergillus SteA (sterile12-like) is a homeodomain-C2/H2-Zn+2 finger transcription factor required for sexual reproduction. Mol. Microbiol. 36:290-301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wiseman, D. W., and R. L. Buchanan. 1987. Determination of glucose level needed to induce aflatoxin production in Aspergillus parasiticus. Can. J. Microbiol. 33:828-830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yager, L. N. 1992. Early developmental events during asexual and sexual sporulation in Aspergillus nidulans. Bio/Technology 23:19-41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yager, L. N., H. O. Lee, D. L. Nagle, and J. E. Zimmerman. 1998. Analysis of fluG mutations that affect light-dependent conidiation in Aspergillus nidulans. Genetics 149:1777-1786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yu, J. H., R. A. Butchko, M. Fernandes, N. P. Keller, T. J. Leonard, and T. H. Adams. 1996. Conservation of structure and function of the aflatoxin regulatory gene aflR from Aspergillus nidulans and A. flavus. Curr. Genet. 29:549-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]