Abstract

Objective

Alcohol screening is uncommon among college students; however, many students display references to alcohol on Facebook. The objective of this study was to examine associations between displayed alcohol use and intoxication/problem drinking (I/PD) references on Facebook and self-reported problem drinking using a clinical scale.

Design

Content analysis and cross-sectional survey

Setting

Participants

Undergraduate students from two state universities between the ages of 18 and 20 with public Facebook profiles

Main exposures

Profiles were categorized into one of three distinct categories: Non-Displayers, Alcohol Displayers and Intoxication/Problem Drinking (I/PD) Displayers.

Outcome measures

An online survey measured problem drinking using the AUDIT scale. Analyses examined associations between alcohol display category and 1) AUDIT problem drinking category using logistic regression, 2) AUDIT score using negative binomial regression, and 3) alcohol-related injury using Fisher’s exact test.

Results

Of 307 profiles identified, 224 participants completed the survey (73% response rate). The average age was 18.8 years, 122 (54%) were female, 152 (68%) were Caucasian, and approximately half were from each university. Profile owners who displayed I/PD were more likely (OR=4.4 [95% CI 2.0-9.4]) to score in the problem drinking category of the AUDIT scale, had 64% (IRR=1.64 [95% CI: 1.27-11.0] higher AUDIT scores overall and were more likely to report an alcohol-related injury in the past year (p=0.002).

Conclusions

Displayed references to I/PD were positively associated with AUDIT scores suggesting problem drinking as well as alcohol-related injury. Results suggest that clinical criteria for problem drinking can be applied to Facebook alcohol references.

INTRODUCTION

Although common, alcohol use is a major cause of both morbidity and mortality among US college students.1 Approximately half of students who use alcohol report direct alcohol-related harms and as many as 1700 college student deaths each year are alcohol-related.2-6 Underage students are also at increased risk for short-term risks related to alcohol use, such as sustaining injury associated with alcohol use.7

Preventing these short and long term negative consequences of problem drinking requires both screening to identify those at risk, and intervention directed towards those who are found to be at risk. Screening tools are available to identify college students at risk for problem drinking and its consequences, such as the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT).8-10 However, screening at the population level among college students remains challenging, as many students do not seek routine or preventive health care at student health centers.11, 12 At present only 12% of college students report undergoing alcohol screening using a standardized instrument.12. Brief interventions have shown promise for reducing problem drinking among young adults.13 However, such interventions cannot have an impact without programs that promote routine screening. Thus, innovative approaches to identifying students at risk for problem drinking in the college population are needed.

One novel approach to identify college students at risk for problem drinking may be social networking sites (SNSs), such as Facebook and MySpace. These web sites are popular among and consistently used by college students; current data suggests between 94 and 98% of students maintain a SNS profile and most report daily use.14-16 SNSs allow students to create a personal web profile, communicate with online friends and build an online social network.17, 18 References to alcohol use are common on SNSs; up to 83% of college students’ SNS profiles reference alcohol.19, 20

The association between SNS references to alcohol use and self-reported alcohol use remains unexplored. Facebook profiles may include disclosures of alcohol use, intoxication or problem drinking. If references to these types of drinking behaviors are valid, these displayed references could potentially aid health care providers or college health systems in identifying students who may benefit from interventions to reduce problem drinking or alcohol-related injury. The objectives of this study were to examine the validity of references to alcohol use and intoxication/problem drinking on public US Facebook profiles applying clinical criteria, then compare these displayed references to self-report using a validated problem drinking scale.

METHODS

This study was conducted between September 1, 2009 and September 15, 2010 and received IRB approval from both the University of Wisconsin and the University of Washington.

Setting and subjects

This study was conducted using the SNS Facebook (www.Facebook.com). This SNS was selected because it is the most popular SNS among our target population of underage college students.15, 21 We investigated publicly available Facebook profiles of undergraduate students who were members of two large state US university Facebook networks. Profile owners were selected for the study if their reported age on the profile was between 18 and 20 years old and the profile showed evidence of activity in the last 30 days. We only analyzed profiles for which we could confirm the profile owner’s identity by calling a phone number listed on either the Facebook profile or the university directory.

Profile selection

In order to reach a target sample size of 200 participants, 307 Facebook profiles owners were invited to participate in the study. Eligible profiles were identified by a random search of the freshmen, sophomore and junior undergraduate classes at our two selected universities using the Facebook search engine. All profiles returned in the search results were assessed sequentially for eligibility until the target sample size was reached. Profiles were excluded if they did not meet search criteria and were thus incorrectly listed, including those who were not undergraduates (N=448), did not meet the age criteria (N=313) or did not display their age (N=49). Profiles were also excluded for privacy settings including having any one of the following sections set to private: information section, wall or photographs (N=1630) or if a profile examination revealed that they would not be reachable for recruitment as no contact information (phone number or email) was listed on the profile or in the university directory (N=303).

Codebook and variables

From each Facebook profile that met inclusion criteria, we recorded demographic data and displayed alcohol reference data, including the coder’s typewritten description of any image references or verbatim text from profiles. If present, identifiable information was removed from text references.

Profiles were categorized into one of three groups. Profiles without any alcohol references were considered “Non-Displayers.”

Profiles with one or more references to alcohol use but no references to intoxication or problem drinking were considered “Alcohol Displayers.” Example references included personal photographs in which the profile owner was drinking from a beer bottle, or text references describing drinking alcohol at a party. Only photographs that contained the profile owner with a clearly labeled alcoholic beverage and text references that explicitly mentioned the profile owner consuming alcohol were coded as an alcohol reference.

Profiles in which there were one or more references to either intoxication or problem drinking behaviors were considered “Intoxication/Problem Drinking (I/PD) Displayers.” Examples of intoxication references included text describing the profile owner as “being wasted” or “getting drunk.” Similar to our previous work, problem drinking was defined using the CRAFFT problem drinking criteria which has been validated in adolescent populations.22, 23 Criteria include driving or riding in a car while intoxicated (C=car), drinking to relax (R=relax), drinking alone (A=alone), forgetting what one did while drinking or blacking out (F=forget), having friends or family ask you to cut down on alcohol (F=friends/family) or getting into trouble related to alcohol use such as being arrested (T=trouble).22-24

Profile evaluation

All profiles were evaluated by one of three trained coders using our research codebook. We have used this codebook in previous work evaluating displayed alcohol references on SNS profiles.19, 24 The coders viewed publicly accessible elements of the Facebook profile including the wall, tagged pictures, profile pictures and bumper stickers in order to determine whether alcohol references were present. One year of profile data was assessed, starting from the date of evaluation and going back to the same date one year prior.

A 20% random subsample of profiles were evaluated by all three coders to test interrater reliability. Cohen’s Kappa statistic was used to evaluate the extent to which there was overall agreement in the coding of the presence or absence of alcohol references on a profile, as well as overall agreement among coders for the categorization of the alcohol references. Cohen’s kappa was 0.85 for the presence or absence of alcohol references present on profiles, and 0.82 for the agreement among coders for the categorization of alcohol references, indicating excellent agreement between coders.25

Recruitment

For profiles that met inclusion criteria, profile owners were called on the phone. After verifying the profile owner’s identity, the study was explained to the profile owner and permission was requested to send an email that contained further information about the study. If the participant consented to receive the email, an email was sent to the profile owner’s university email account that provided detailed information about the study as well as a link to the online survey. Profile coding was not discussed with participants. The survey was administered online via a Catalyst WebQ online survey engine. Survey respondents were provided a $15 iTunes gift card as compensation.

Survey

The online survey evaluated alcohol use and problem drinking behaviors using the Alcohol Use Disorder Identification Test (AUDIT), which has been validated among college students.8-10 A previous study in college students found the AUDIT to have a sensitivity of 0.84 and specificity of 0.71 for identifying problem alcohol use.9 The AUDIT is a 10 question scale with most answers on a 0-4 Likert scale assessing consumption, dependence and harm/consequences of alcohol use. Questions include an assessment of the frequency of drinking alcohol (never, monthly or less, 2-4 times a month, 2-3 times a week, 4 or more times a week), frequency of binge drinking (never, less than monthly, monthly, weekly, daily) as well as negative consequences associated with alcohol use. AUDIT scores can theoretically range from 0 to 40; a score of 8 or higher indicates the person is at risk for problem drinking.9

Analysis

All statistical analyses were conducted using STATA version 11.0 (Statacorp, College Station, TX). Demographic characteristics and Facebook displayed alcohol categories were summarized using descriptive statistics. Bivariate comparisons between demographic characteristics and Facebook displayed alcohol categories were conducted using Fisher’s exact test and Chi squared tests when appropriate. We then examined the relationship between AUDIT scores and displayed alcohol categories using two approaches. First, participants who had a total AUDIT score of 8 or higher were categorized as being at risk for problem drinking as described in previous literature.9 We assessed the odds of being in the AUDIT category of at risk for problem drinking and displayed alcohol categories using logistic regression, adjusting for age and gender and using non-displayer as the referent. Second, the relationship between total AUDIT score and Facebook displayed alcohol category were examined. Because AUDIT scores were ordinal and right-skewed with an over-representation of participants with zero scores we used zero-inflated negative binomial (ZINB) regression..26 ZINB is designed to apply to non-negative ordinal or count data with an over-representation of zeros, outcomes are represented as incidence rate ratios.27 Both forwards and backwards stepwise ZINB regression models were conducted with age and gender as covariates to determine the best model fit. To explore gender differences the ZINB model was run separately by gender as well as with an interaction term. Finally, as an exploratory analysis to assess alcohol-related injury, we used responses to the AUDIT question: “Have you or someone else ever been injured as a result of your alcohol use?” Response options included: never, yes but not in the past year, and yes in the past year. The relationship between alcohol display category and alcohol-related injury was examined using Fisher’s exact test.

RESULTS

Subjects

A total of 307 profile owners were invited to participate and 224 participants completed the survey (73% response rate). Participants had an average age of 18.8, were 54.5% female and 67.9% Caucasian. Approximately half of participants were from each university. Please see Table 1 for further descriptive information.

Table 1. Participant information.

| N | % | Mean (SD) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 224 | 18.8 (0.7) | |

| 18 | 77 | 34.4 | |

| 19 | 118 | 52.7 | |

| 20 | 29 | 12.9 | |

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

| Male | 102 | 45.5 | |

| Female | 122 | 54.5 | |

|

| |||

| State | |||

| Washington | 101 | 45.1 | |

| Wisconsin | 123 | 54.9 | |

|

| |||

| Race | |||

| Caucasian/White | 152 | 67.9 | |

| Asian | 38 | 17.0 | |

| Other | 8 | 3.6 | |

| Multiracial | 17 | 7.6 | |

| Missing | 9 | 4.0 | |

|

| |||

| Alcohol display category | |||

| Non-Displayer | 144 | 64.3 | |

| Alcohol Displayer | 44 | 19.6 | |

| Intoxication/Problem Drinking | |||

| Displayer | 36 | 16.1 | |

|

| |||

| AUDIT Score | 216 | 5.8 (4.9) | |

| Not a Problem Drinker (<8) | 145 | 64.7 | |

| Problem Drinker (>=8) | 71 | 31.7 | |

| Missing | 8 | 3.6 | |

Descriptive and Bivariate Data

Facebook displayed alcohol categories

Of Facebook profiles coded, 64.3% had no alcohol references displayed on the profile (Non-Displayers), 19.6% displayed references to alcohol use (Alcohol Displayers), 16.1% displayed references to intoxication or problem drinking (I/PD Displayers). There were no differences among Non-Displayers, Alcohol Displayers or I/PD Displayers for age, gender or between the two universities. I/PD Displayers were more likely to be Caucasian (83%) compared to other races (p=0.03). Table 2 illustrates these bivariate relationships between demographic information and Facebook displayed alcohol categories.

Table 2. Participant information by Alcohol Display Category.

| Non-Displayer | Alcohol Displayer |

Intoxication/Problem Drinking Displayer |

p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||

| N | % | N | % | N | % | ||

| Age | 144 | 44 | 36 | 0.2791 | |||

| 18 | 53 | 36.8 | 16 | 36.4 | 8 | 22.2 | |

| 19 | 76 | 52.8 | 22 | 50 | 20 | 55.6 | |

| 20-21 | 15 | 10.4 | 6 | 13.6 | 8 | 22.2 | |

|

| |||||||

| Gender | 0.3151 | ||||||

| Male | 67 | 45.9 | 16 | 35.6 | 19 | 52.8 | |

| Female | 77 | 52.7 | 18 | 62.2 | 17 | 47.2 | |

|

| |||||||

| State | 0.2511 | ||||||

| Washington | 68 | 46.6 | 15 | 33.3 | 18 | 50.0 | |

| Wisconsin | 76 | 52.1 | 29 | 64.4 | 18 | 50.0 | |

|

| |||||||

| Race | 0.0332 | ||||||

| Caucasian/White | 89 | 61.0 | 33 | 73.3 | 30 | 83.3 | |

| Asian | 29 | 19.9 | 6 | 13.3 | 3 | 8.3 | |

| Other | 3 | 2.1 | 2 | 4.4 | 3 | 8.3 | |

| Multiracial | 15 | 10.3 | 2 | 4.4 | 0 | 0.0 | |

| Missing | 8 | 5.5 | 1 | 2.2 | 0 | 0.0 | |

|

| |||||||

| AUDIT Score | 136 | 44 | 36 | <0.0013 | |||

| Not a Problem Drinker (<8) | 103 | 70.5 | 27 | 60.0 | 15 | 41.7 | <0.0011 |

| Problem Drinker (>=8) | 33 | 22.6 | 17 | 37.8 | 21 | 58.3 | |

| Missing | 8 | 5.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | |

p-value from Fisher’s exact test

p-value from Chi-Square test

p-value from bivariate zero-inflated negative binomial regression

AUDIT score

A total of 216 participants completed all AUDIT questions and received a total AUDIT score. Total AUDIT scores ranged from 0 to 26, with a mean of 5.8 (+/-4.9) and a median of 5. Using the standard cutoff of at-risk for problem drinking as a score of 8 or higher, 35.4% of participants scored into the at-risk for problem drinking category.28, 29

AUDIT Problem drinking category and Facebook displayed alcohol categories

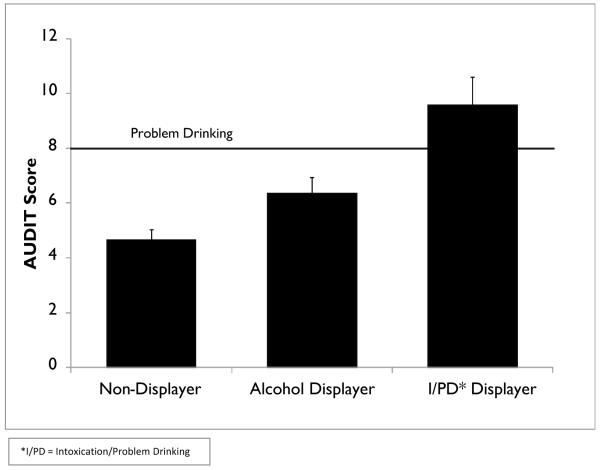

Displayed alcohol references on Facebook were positively related to being categorized as at risk for problem drinking: 58.3 % of I/PD Displayers met criteria for at-risk problem drinking category, compared to 37.8% of Alcohol Displayers and 22.6% of Non-Displayers (p<0.001). In a logistic regression model, compared to Non-Displayers, I/PD Displayers were more likely (OR=4.4, 95% CI: 2.0-9.4) to be at-risk for problem drinking. Findings for Alcohol Displayers were not statistically significant (OR=1.97, 95% CI: 0.95-4.0). Figure 1 illustrates these data.

Figure 1.

Association between displayed alcohol categories on Facebook and AUDIT problem drinking score

AUDIT score and Facebook displayed alcohol categories

The mean AUDIT score for I/PD Displayers was 9.5 (+/− 6.0), the mean AUDIT score for Alcohol Displayers was 6.7 (+/− 4.3) and the mean AUDIT score for Non-Displayers was 4.7 (+/− 4.0), (p<0.001). Neither age nor gender were significant in forwards and backwards regression, thus the ZINB model included only AUDIT score and Facebook displayed alcohol categories. Compared to Non-Displayers, I/PD displayers had 1.64 times higher AUDIT scores (95% CI: 1.27-11.0) (p<0.001). Compared to Alcohol Displayers, I/PD Displayers had 1.48 times (95% CI: 1.10-10.0) higher AUDIT scores. The difference in AUDIT scores between Alcohol Displayers and Non-Displayers did not reach statistical significance.

Gender differences

When models were run separately by gender, the relationship between AUDIT score and Facebook displayed alcohol category showed coefficient estimates for men nearly twice as large as for women. Males who were I/PD Displayers had an 89% higher AUDIT score compared to males who were Non-Displayers (p=0.001) Females who were I/PD Displayers were not significantly more likely to have a higher AUDIT score (37% higher, p=0.07). However, when gender was included in the model these differences did not reach statistical significance.

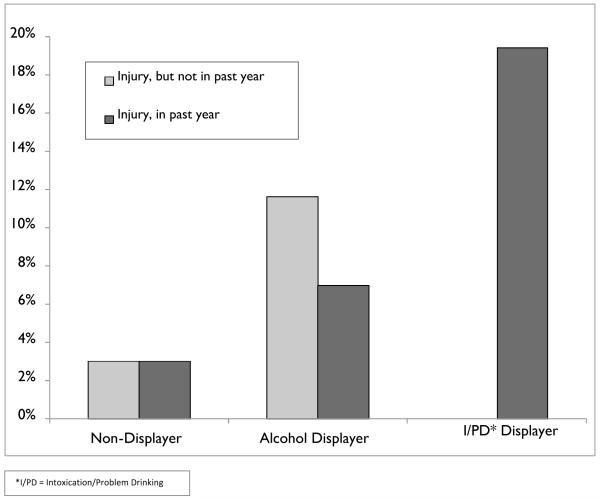

Facebook alcohol display category and alcohol-related injury

Overall, 160 (88%) participants reported that they had never experienced an alcohol-related injury, 8 (4%) participants reported a history of alcohol-related injury but not in the last year, and 14 (5%) reported an alcohol-related injury in the past year. I/PD Displayers were more than twice as likely to report an alcohol-related injury in the past year (19% versus 7%) compared to Alcohol Displayers (p=0.002), and more than 6 times more likely than Non-Displayers (19% versus 3%). Figure 2 illustrates these data.

Figure 2.

Association between Facebook alcohol display category and self-report of alcohol-related injury

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to demonstrate an association between specific content of displayed alcohol references on Facebook evaluated using clinical screening criteria, and self-reported problem drinking behaviors and consequences. Our data illustrates that participants who chose to display references to intoxication or problem drinking on publicly available Facebook profiles were more likely to meet problem drinking criteria using the AUDIT score compared to participants who displayed either no alcohol references, or alcohol references, on their Facebook profiles.

Our findings further illustrate that mean AUDIT scores increase as categories of displayed alcohol references on Facebook profile escalate. The lowest mean AUDIT scores were amongst Non-Displayers, higher mean AUDIT scores were found among Alcohol Displayers, and highest mean AUDIT scores were among I/PD Displayers. The I/PD Displayers group was the only group with mean AUDIT score in the problem drinking category. Additionally, I/PD Displayers were more likely to report experiencing an alcohol-related injury in the last year. Facebook displays of intoxication and problem drinking may be indicators of both overall problem drinking concerns, as well as short-term morbidity related to alcohol use in the college population. Thus, it can be concluded that there is likely a difference in clinical relevance between displayed alcohol references and I/PD references as representations of college alcohol use.

Our findings related to gender suggest that the association between I/PD Displayer and AUDIT score may be stronger for males than females. Compared to female college students, male college students are more likely to drink alcohol as well as engage in binge drinking.30, 31 Further, males are less likely to be seen in clinic; approximately 38% of males report having a preventive health check in the past year compared to 69% of females.11, 32 Thus, if Facebook presents a valid complementary method of identifying males at high risk for problem drinking, then this method would likely capture a population with high rates of problem drinking and low likelihood of seeking care in a clinic.

Our study findings are limited in that we only examined publicly available profiles on one SNS. Therefore we cannot generalize our findings to profiles that have security set to private, or to profiles on other SNSs. It is important to note that SNS profile privacy settings are not permanent; profile owners may change their privacy settings at any time or to reflect what security upgrades are offered by Facebook. It is unclear whether profile owners who maintained a private profile at the time of this study would be more likely, or less likely, to display alcohol references. For this study, the finding that our prevalence of problem drinking was consistent with other national estimates suggests our sample was representative.29 Study findings are also limited in that our study sample included very few minority and no African American participants, which is consistent with the demographic of our universities.

Despite these potential limitations, our findings have important implications. Although approximately half of the screened profiles were excluded due to privacy settings, at present only 12% of college students report undergoing alcohol screening using a standardized instrument.12 Facebook is used by up to 98% of the college population, and about half of college students’ profiles in our study were public; thus, use of Facebook as a complementary and innovative screening tool still represents a substantial improvement over the norm.12 Our goal in evaluating publicly available profiles was to assess information that could be viewed by any Facebook user’s peers, parents, professors or any other university affiliates. By assessing public profiles, our goal was to identify a subset of the Facebook population that may be accessible for future intervention efforts.

There are several ways in which these findings could contribute towards enhancing alcohol screening or intervention efforts among college students. Attention to both privacy concerns and ethics are paramount to the success of any future research or clinical efforts involving SNSs.33, 34 A first option is to use displayed information on SNS profiles as a way to identify students at risk and recommend that these students be seen in clinic for further screening or counseling. Findings in our paper suggest that approximately half of profiles were excluded due to privacy settings. Since the time of our data collection, Facebook profile security settings have again changed and more options exist to set sections of the profile to private while leaving the profile itself publicly available. It is possible that more profiles may now be publicly available. As Facebook security is ever-changing, it is likely that an ideal target to undertake initial screening is someone known to the college student who would have full access to profile content. This approach may also lead to better acceptance by the profile owner if he or she is approached with concerns and a request to undergo further clinical screening. It is possible that trusted peer leaders such as dormitory resident advisors could receive training in identification of at-risk students from Facebook I/PD references. These peer leaders could then provide resources to a student who displayed repeated concerning references on Facebook. Our findings suggest that training in CRAFFT criteria could allow such peer leaders to distinguish a student who displays references to problem drinking from students who may display references to alcohol on Facebook.

Another consideration is the role of the clinician in these screening efforts. It is unlikely that a clinician would have time or training to undertake evaluation of Facebook profiles in the college health setting. However, clinicians may be approached by parents, professors or administrators regarding the content of a student’s Facebook profile. These study findings can be used towards offering evidence-based guidance that students who display references to intoxication or problem drinking on Facebook should undergo clinical screening for problem alcohol use.

A final consideration is the use of targeted messaging based on the displayed content on a SNS profile. This approach would provide messages to Facebook profile owners regardless of privacy settings. Advertisements on Facebook are triggered by keywords displayed on the profile. For example, displayed text references to terms such as “diet” will trigger advertisements for weight loss services displayed next to the profile. It is possible that universities could choose to place messages, or educational materials such as an online alcohol screening program, targeted to keywords representing problem drinking behaviors. Our findings suggest that targeting keywords that relate to intoxication or problem drinking, rather than to general keywords regarding alcohol, may provide an innovative method to deliver a tailored message to a target population. Before such efforts can move forward, a better understanding of what type of messages would be acceptable to the college population as “pop up” advertisements needs to be undertaken.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by award R211AA017936 from NIAAA as well as award K12HD055894 from NICHD. These funding agencies had no role in the design or conduct of the study, no role in data collection or analysis, and no role in preparation or review of the manuscript. Megan Moreno had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors would like to express gratitude for the contributions of the following people: Hope Villiard, Megan Pumper, Lauren Kacvinsky and Kaitlyn Bare for their contributions to data collection in this project, and to Marcia Scott, PhD for her support and advice regarding this project..

REFERENCES

- 1.Association ACH . American College Health Association: National College Health Assessment II: Reference Group Data Report Fall 2008. American College Health Association; Baltimore: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Abbey A. Alcohol-related sexual assault: a common problem among college students. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002:118–28. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hingson R, Heeren T, Winter M, Wechsler H. Magnitude of alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24: changes from 1998 to 2001. Annu Rev Public Health. 2005;26:259–79. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hingson RW, Zha W, Weitzman ER. Magnitude of and trends in alcohol-related mortality and morbidity among U.S. college students ages 18-24, 1998-2005. J Stud Alcohol Drugs Suppl. 2009:12–20. doi: 10.15288/jsads.2009.s16.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cooper ML. Alcohol use and risky sexual behavior among college students and youth: evaluating the evidence. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002:101–17. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giancola PR. Alcohol-related aggression during the college years: theories, risk factors and policy implications. J Stud Alcohol Suppl. 2002:129–39. doi: 10.15288/jsas.2002.s14.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Are you Twittering, getting friends on Facebook, and YouTube? Same-Day Surgery. 2009;33:105–7. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kokotailo PK, Egan J, Gangnon R, Brown D, Mundt M, Fleming M. Validity of the alcohol use disorders identification test in college students. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2004;28:914–20. doi: 10.1097/01.alc.0000128239.87611.f5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fleming MF, Barry KL, MacDonald R. The alcohol use disorders identification test (AUDIT) in a college sample. Int J Addict. 1991;26:1173–85. doi: 10.3109/10826089109062153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schmidt A, Barry KL, Fleming MF. Detection of problem drinkers: the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) South Med J. 1995;88:52–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alsac B. Blog, Twitter or Facebook for health. SportEX Health (14718154) 2008:14–6. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foote J, Wilkens C, Vavagiakis P. A national survey of alcohol screening and referral in college health centers. J Am Coll Health. 2004;52:149–57. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grossberg PM, Brown DD, Fleming MF. Brief physician advice for high-risk drinking among young adults. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:474–80. doi: 10.1370/afm.122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis K, Kaufman J, Christakis N. The Taste for Privacy: An Analysis of College Student Privacy Settings in an Online Social Network. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2008;14:79–100. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buffardi LE, Campbell WK. Narcissism and social networking Web sites. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2008;34:1303–14. doi: 10.1177/0146167208320061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ross C, Orr ES, Sisic M, Arseneault JM, Simmering MG, Orr RR. Personality and motivations associated with Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior. 2009;25:578–86. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ellison NB, Steinfield C, Lampe C. The benefits of Facebook “Friends:” Social Capitol and College Students’ Use of Online Social Network Sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication. 2007:12. [Google Scholar]

- 18.boyd d, Cambridge MA. Why Youth (Heart) Social Networking Sites: The Role of Networked Publics in Teenage Social Life. In: Buckingham D, editor. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Learning: Youth, Identity and Media Volume. Vol. 2007. MIT press; pp. 119–42. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Moreno MA, Parks MR, Zimmerman FJ, Brito TE, Christakis DA. Display of health risk behaviors on MySpace by adolescents: Prevalence and Associations. Archives of Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine. 2009;163:35–41. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2008.528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yen C, Hsiao R, Ko C, Yen J, Huang C, et al. The relationships between body mass index and television viewing, internet use and cellular phone use: the moderating effects of socio-demographic characteristics and exercise. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2010;43:565–71. doi: 10.1002/eat.20683. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Google Ad Planner [Accessed April 16, 2010];2010 https://www.google.com/adplanner/planning/site_details#siteDetails?identifier=facebook.com&geo=US&trait_type=1&lp=false.

- 22.Knight JR, Shrier LA, Bravender TD, Farrell M, Vander Bilt J, Shaffer HJ. A new brief screen for adolescent substance abuse. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1999;153:591–6. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.153.6.591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilson CR, Sherritt L, Gates E, Knight JR. Are clinical impressions of adolescent substance use accurate? Pediatrics. 2004;114:e536–40. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-0098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McGee JB, Begg M. What medical educators need to know about “Web 2.0”. Medical Teacher. 2008;30:164–9. doi: 10.1080/01421590701881673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kimberlin CL, Winterstein AG. Validity and reliability of measurement instruments used in research. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2008;65:2276–84. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Long S, Freese J. Regression Models for Categorical Dependent Variables using Stata. Stata Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Afifi AA, Kotlerman JB, Ettner SL, Cowan M. Methods for improving regression analysis for skewed continuous or counted responses. Annu Rev Public Health. 2007;28:95–111. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.28.082206.094100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Graffeo Cybertherapy meets Facebook, Blogger, and Second Life; an Italian Experience. Annual Review of Cybertherapy and Telemedicine 2009. 2009;144:108–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fogel J, Nehmad E. Internet social network communities: Risk taking, trust, and privacy concerns. Computers in Human Behavior. 2009;25:153–60. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cardon PW, Marshall B, Norris DT, Cho JY, Choi J, et al. ONLINE AND OFFLINE SOCIAL TIES OF SOCIAL NETWORK WEBSITE USERS: AN EXPLORATORY STUDY IN ELEVEN SOCIETIES. J Comput Inf Syst. 2009;50:54–64. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wechsler H, Dowdall GW, Davenport A, Castillo S. Correlates of college student binge drinking. Am J Public Health. 1995;85:921–6. doi: 10.2105/ajph.85.7.921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Cain J, Scott DR, Akers P. Pharmacy students’ Facebook activity and opinions regarding accountability and e-professionalism. Am J Pharm Educ. 2009;73:104. doi: 10.5688/aj7306104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Correa T, Hinsley AW, de Zuniga HG. Who interacts on the Web?: The intersection of users’ personality and social media use. Computers in Human Behavior. 26:247–53. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moreno MA, Fost NC, Christakis DA. Research ethics in the MySpace era. Pediatrics. 2008;121:157–61. doi: 10.1542/peds.2007-3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]