Abstract

Given strong regional specialization of the brain, cerebral angiogenesis may be regionally modified during normal aging. To test this hypothesis, expression of a broad cadre of angiogenesis-associated genes was assayed at the neurovascular unit (NVU) in discrete brain regions of young vs. aged mice by laser capture microdissection coupled to quantitative real-time PCR. Complementary quantitative capillary density/branching studies were performed as well. Effects of physical exercise were also assayed to determine if age-related trends could be reversed. Additionally, gene response to hypoxia was probed to highlight age-associated weaknesses in adapting to this angiogenic stress. Aging impacted resting expression of angiogenesis-associated genes at the NVU in a region-dependent manner. Physical exercise reversed some of these age-associated gene trends, as well as positively influenced cerebral capillary density/branching in a region-dependent way. Lastly, hypoxia revealed a weaker angiogenic response in aged brain. These results suggest heterogeneous changes in angiogenic capacity of the brain during normal aging, and imply a therapeutic benefit of physical exercise that acts at the level of the NVU.

Keywords: brain microvasculature, cerebral angiogenesis, normal aging, laser capture microdissection, neurovascular unit

1. Introduction

Several reports on aging humans and rodents indicate angiogenesis – the sprouting of new blood vessels from pre-existing vasculature (Skalak, 2005) – is compromised in peripheral tissues by normal aging (Reed and Edelberg, 2004; Rivard, et al., 1999; Sadoun and Reed, 2003), Additionally, gross analysis of cerebrovascular architecture, assessment of capillary density, and measurement of cerebral blood volume point toward progressive failure of cerebral angiogenesis during aging (Black, et al., 1989; Hof, 2004; Riddle, et al., 2003) – a scenario that might contribute to a host of age-related CNS disorders with vascular involvement, including stroke, vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (Popa-Wagner, et al., 2010). Consistent with this account are reports that aging negatively impacts expression of select angiogenic factors in the brain (Benderro and Lamanna, 2011; Mitschelen, et al., 2011). However, despite provocative evidence linking age with diminished angiogenic capacity, several factors seriously complicate interpreting the effects of aging on brain angiogenesis.

One, is that the brain ages asymmetrically (Berchtold, et al., 2008; Mora, et al., 2007), prompting caution in extrapolating aging effects on peripheral angiogenesis to what happens in the brain (Petcu, et al., 2010), and when comparing brain angiogenic events in young and aged subjects (Sonntag, et al., 2007). It is additionally worth noting that, as certain brain regions appear more prone to injury and/or stress with increasing age (Mattson and Magnus, 2006), local impairments in angiogenic activity might contribute to these vulnerabilities.

Two, is that many growth factors affecting cerebral angiogenesis are also expressed by the neural parenchyma – the so-called angioneurins (Segura, et al., 2009; Zacchigna, et al., 2008) – and impact neurogenesis and other neural functions. Separation of vascular tissue from the bulk of the parenchyma is thus necessary to avoid confounding angiogenic and neurogenic activities. The neurovascular unit (NVU), which lies at the interface between vascular and neural tissue and is comprised of endothelial cells, pericytes, astrocytes and neurons (Hawkins and Davis, 2005; Lok, et al., 2007), is regarded as a hub of angiogenic activity (Arai, et al., 2009; Tam and Watts, 2010; Ward and Lamanna, 2004). It is therefore expected that targeted analysis of NVU tissue would yield information most closely related to angiogenesis.

Three, is the matter of ‘angiogenic potential,’ a term that reflects the equilibrium expression of the pro- and anti-angiogenic factors that collectively orchestrate the sequential steps of angiogenesis (Aranha, et al., 2010; Klement, et al., 2007; Wykrzykowska, et al., 2009). While considerable efforts have highlighted the role(s) of single or small cohorts of angiogenic genes, appreciation is gaining that angiogenesis is under direction of an ‘angiome’ representing the totality of angiogenesis-associated genes (Carmeliet, 2003; Dore-Duffy and LaManna, 2007; Kumar, et al., 1998). Extending this view, age-related changes in brain angiogenesis may be due less to a lone-gene culprit, than to altered angiogenic potential resulting from coordinated shifts in expression of multiple genes within the angiome. Moreover, given asymmetric aging of the brain, the particular genes involved in such shifts may be region-specific. The considerable regional endothelial heterogeneity that exists in the brain (Ge, et al., 2005) underscores this point. Comparing a multitude of angiogenesis-associated genes across several brain regions would thus provide novel detail regarding regionalization of brain aging.

Accordingly, our objective was to perform the first systematic and detailed comparison of the effects of normal aging on expression of 32 angiogenesis-associated genes by the NVU in multiple brain regions. Experiments focused on three regions – cortex, hippocampus and white matter – all of which exhibit age-related vulnerabilities of clinical significance. Immunohistochemistry-guided laser capture microdissection coupled to qRT-PCR (Macdonald, et al., 2008) was employed to selectively examine gene expression at the NVU, and complementary quantitative 3-D analysis of capillary density/branching was performed as well. Angiogenic potential was also determined following a regimen of treadmill running to see if physical exercise could reverse regional age-related trends. Additionally, angiogenic potential of the cortex was assessed following hypoxia, to determine how aging affects a multi-gene response to this normally angiogenic stimulus.

2. Methods

2.1 Animals

To minimize effects due to gender and health status, only male C57Bl/6J mice obtained from the National Institute of Aging aged rodent colonies were used. Mice of both age groups: young (6–8 months) and aged (22 – 24 months) were obtained from the same source. This age range was chosen as it encompasses a healthy, normal adult lifespan, and C57Bl/6J mice were specifically selected as they exhibit decidedly less animal-to-animal variability in anatomy of the cerebrovasculature in comparison to both other inbred strains and genetically heterogeneous outbred strains (Ward, et al., 1990). Mice were euthanized by CO2 inhalation, in accordance with measures stipulated by the Animal Care and Use Guidelines of the University of Connecticut Health Center (Animal Welfare Assurance # A3471-01).

2.2 Tissue preparation for Immuno-LCM

Brains were snap-frozen in dry ice-cooled 2-methylbutane (Acros; Geel, Belgium), and stored at −80°C. Frozen brain was embedded in cryomatrix compound (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) prior to sectioning. Coronal sections (7 µm) were cut on a Microm HM 505M cryostat (Mikron Instruments; Oakland, NJ) and affixed to uncoated, pre-cleaned glass slides (Fisher Scientific, Pittsburgh, PA) and stored in a slide box at −80° C. Tissue was processed for RNA within a week of sectioning.

2.2 Immunostaining for Immuno-LCM

Immunostaining was performed as detailed (Kinnecom and Pachter, 2005; Macdonald, et al., 2008; Macdonald, et al., 2010). Sections were fixed in 75% ethanol, on ice, for 3 min prior to staining. Brain microvascular endothelial cells (BMEC) were labeled first for 3 min by immunohistochemistry using monoclonal rat anti-mouse CD31 antibody (BD Biosciences; San Jose, CA) diluted 1:10 in PBS + 0.2% Tween-20 (diluent). CD31 immunostaining was followed by incubation with anti-rat biotinylated secondary antibody (diluted 1:350 in PBS + 0.2% Tween-20) for 2 min, and then alkaline phosphatase detection using the Vectastain ABC kit with NBT/BCIP as substrate (Vector Labs, Burlingame, CA). Importantly, CD31 is expressed by all endothelial cells of the vascular tree (Zhang, et al., 2002), and endogenous alkaline phosphatase is expressed by capillaries and arterioles and used to identify microvessels in the aged brain (Moody, et al., 2004; Zoccoli, et al., 2000). This combination thus leads to robust staining of the entire endothelium, even should CD31 expression diminish with age. Next, perivascular astrocyte endfeet were immunofluorescently stained for 8 min using anti-mouse GFAP antibody (Sigma; St Louis, MO) diluted 1:10 in blocking buffer (5% normal goat serum, 0.2% Tween-20 in PBS), followed by an Alexa 488-conjugated goat anti-rabbit IgG antibody (Molecular Probes; Eugene, OR), diluted 1:10 in blocking buffer. RNAsin® RNAse inhibitor (Promega, Madison, WI) was added to all staining reagents. Pericytes and perivascular neuronal processes – also critical contributors to the NVU (Lok, et al., 2007) and angiogenesis (Dore-Duffy and LaManna, 2007; Lok, et al., 2007; Ward and Lamanna, 2004; Zoccoli, et al., 2000) – are contained within the perivascular space subtended by astrocyte foot-processes and were included with NVU tissue retrieved.

2.3 Cresyl violet staining

Cresyl violet staining (1% in 0.25% acetic acid) was performed immediately after the double-immunostaining to demarcate the hippocampus and subcortical white matter (corpus callosum), and did not adversely affect RNA recovery. Immediately after immunostaining, sections were dehydrated through graded alcohol and xylenes as described (Macdonald, et al., 2008).

2.4 Laser capture microdissection (LCM)

A PixCell IIe laser capture microscope (ABI, Foster City, CA) was used to procure NVU tissue as previously detailed by our laboratory (Macdonald, et al., 2008; Macdonald, et al., 2010; Murugesan, et al., 2011). Prior efforts intentionally separated BMEC from astrocyte end-feet and pericytes. For the present studies, however, our objective was to include all recognized cellular NVU elements (including neuronal processes) as they are major producers of angiogenic factors (Dore-Duffy and LaManna, 2007; Lok, et al., 2007; Ward and Lamanna, 2004). Only microvessels < 10 µm in diameter – representing capillaries (Macdonald, et al., 2010) – were captured. For cortex and corpus callosum, coronal sections were taken between bregma 1.34 mm to 0.5 mm sterotaxic co-ordinates (George and Keith, 2001), which included primary and secondary motor cortex. Hippocampus was taken from within bregma −2.92 and −3.40 mm.

Regional NVU samples were captured and processed in pairs from young and aged mice during each LCM session, and collected onto separate HS caps (ABI). After LCM was completed, tissue was solubilized in TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and stored tissue frozen at −80° C. NVU tissue from consecutive sections of the same mouse brain were pooled together for each brain region, until a total of 2500 shots’ worth was achieved. This allowed for analysis of 12 genes (including reference gene RPL19). Genes that were either undetectable or whose Ct values were ≥ 36 cycles by qRT-PCR were listed as “undet” in Suppl. Table 2. The process was repeated for n=3 mice per age and brain region.

2.5 RNA Isolation and cDNA synthesis

RNA was isolated from pooled TRIzol-solubilized tissue extracts as described (Macdonald, et al., 2008). Significantly, this laboratory has shown such pooling does not cause statistically significant variability in qRT-PCR measurements (Macdonald, et al., 2008; Macdonald, et al., 2010). RNA was treated with Turbo DNAse (Ambion; Austin, TX) and then reverse-transcribed using SuperScript III reverse transcriptase (Invitrogen) as reported (Macdonald, et al., 2008). Resulting cDNA was stored at −20° C until used for further analysis.

2.6 Quantitative qRT-PCR

Gene expression (relative to housekeeping gene RPL19) was determined using PRISM 7900 Sequence Detection System Version 2.3 (ABI, Foster City, CA), and SYBR green (ABI, Foster City, CA) fluorescence as detailed previously (Macdonald, et al., 2008; Macdonald, et al., 2010). Dissociation curves for each gene were analyzed to ensure specific amplicon replication, and all reactions performed in duplicates. Controls included no template control, no reverse transcriptase control, and positive control (cDNA of isolated brain microvessels). To further exclude any trace genomic DNA, intron-spanning primer pairs were designed for all the genes, using Primer Express 3.0 software. Primer sequences for the angiogenesis-associated genes probed are listed in Suppl. Table 1.

2.7 Determination of cerebral microvascular patency

Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-conjugated Lycopersicon esculentum lectin (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MI) was diluted to 0.52 µmol lectin/l in PBS. Patent microvessels were labeled by injecting 0.3 ml of lectin into the tail vein (Dickie, et al., 2006). Lectin was allowed to circulate for 15 min before sacrifice. Co-localization of lectin-stained (green) and CD31+ (red) vessels was quantified using the co-localization analysis plugin in ImageJ 1.44 (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD) to calculate Manders overlap co-efficient (R) (Manders, et al., 1992).

2.8 Microvessel density

As 2-D analysis is more prone to sampling error (Ingraham, et al., 2008), a confocal 3-D rendering approach (Zhou, et al., 2008) was employed to measure capillary density. Specifically, 3 × 50-µm thick frozen sections, taken 200 µm apart, were obtained from each region of a single brain for each experimental condition. Sections were immunostained with anti-CD31 antibody primary antibody and Alexa 555 goat anti-rat IgG secondary antibody (Invitrogen) to highlight microvessels. In each section, 3 fields (500 µm × 300 µm) were sampled. Images were acquired on a Zeiss LSM 510 laser scanning confocal microscope, and optical slices (at 2-µm intervals) obtained using a 20× objective. Acquired z-stacks were background subtracted and quantitative 3-D analysis performed using Imaris version 6.2 × 64 software (Bitplane Inc. Saint Paul, MN). Each z-stack was thresholded and the “filament tracker” module used to generate a 3-D traced outline of immunostained vessels. As with LCM, only microvessels < 10µm in diameter – defined as capillaries (Macdonald, et al., 2010) – were analyzed. Total capillary volume, length and branch points/section in 3 fields were obtained. Capillary density was defined as capillary length/unit tissue volume, to lessen potential “artifacts” due to age-related changes in brain volume (Ingraham, et al., 2008). The process was repeated for n=3 mice per condition.

2.09 Physical exercise (treadmill training)

A treadmill exercise regimen was used similar to that previously described to stimulate angiogenesis in the cerebral cortex of aged rats (Ding, et al., 2006) and in accordance with Animal Care and Use Guidelines of the University of Connecticut Health Center (2008-466). Animals were randomly assigned to exercise or non-exercise control groups, and were run on a two-lane, 80-AP2MGA AcuPacer treadmill (Accuscan Instruments, Columbus, OH). Treadmill speed was increased incrementally: 1 m/min for the first 2 min; 5 m/min for the next 5 min; 10 m/min for the next 5 min; and 13.5 – 14.5 m/min for the final 20 minutes (32 min total running time). This regimen was carried out 5 days/week for 4 consecutive weeks, and produced exercise with relative intensity estimated at ~70–85% maximal oxygen uptake. No shock treatment was administered, so as to minimize confounding effects due to psychological stress and/or pain (Hayes, et al., 2008). Non-exercised controls underwent the first 2 min of walking at 1 m/min, and then remained on the apparatus for the remaining time with the treadmill belt kept stationary. Body weight was measured every 3 days, and no significant weight loss due to exercise was noted in either groups. n = 3 animals was used for all exercise and control groups.

2.10 Chronic mild hypoxia

Mice were exposed to chronic mild hypoxia, in accordance with Animal Care and Use Guidelines of Yale University Animal Care committee (IUCAC 2008-07366). Exposure to hypoxia was achieved as described (Ingraham, et al., 2008; Li, et al., 2009), using a specialized plexiglass chamber manufactured by BioSpherix, Ltd., (Lacona, NY). Oxygen content within the chamber was adjusted to 10.0% ± 1% by a nitrogen/compressed air gas delivery system that mixes nitrogen with room air using a BioSpherix, Ltd. Pro:OX compact oxygen controller to achieve desired O2 levels. The chamber has a small, quiet fan mounted in proximity to the O2 sensor inside the chamber to provide forced circulation and almost instantaneous homogenization of gases. Temperature and lighting were maintained at standard vivarium levels, as was humidity level within the chamber. Oxygen levels were checked and recorded by staff at least twice daily. Cohorts of both young and aged mice were subjected to hypoxia for 8 days. This time point was chosen as maximal cerebral endothelial cell proliferation has been observed after 4 days, and astrocyte activation noted between 7–14 days, following chronic mild hypoxia in young C57Bl/6J mice (Li, et al., 2010). Age-matched control animals remained in identical cages under normoxic conditions throughout.

2.11 Statistical Analyses

Relative gene expression values are given as mean ± SEM. A two-tailed student’s t-test was employed to assess statistical significance in gene expression values between NVU samples from the two age groups, for each region, separately. Interactive effects between age and brain region on expression of angiogenesis-associated genes, was assessed using 2-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni post hoc analyses using GraphPad Prism 5. Results were significant at a p ≤ 0.05.

3. Results

3.1 LCM/qRT-PCR as a tool to selectively examine angiogenic potential of the NVU in the aging brain

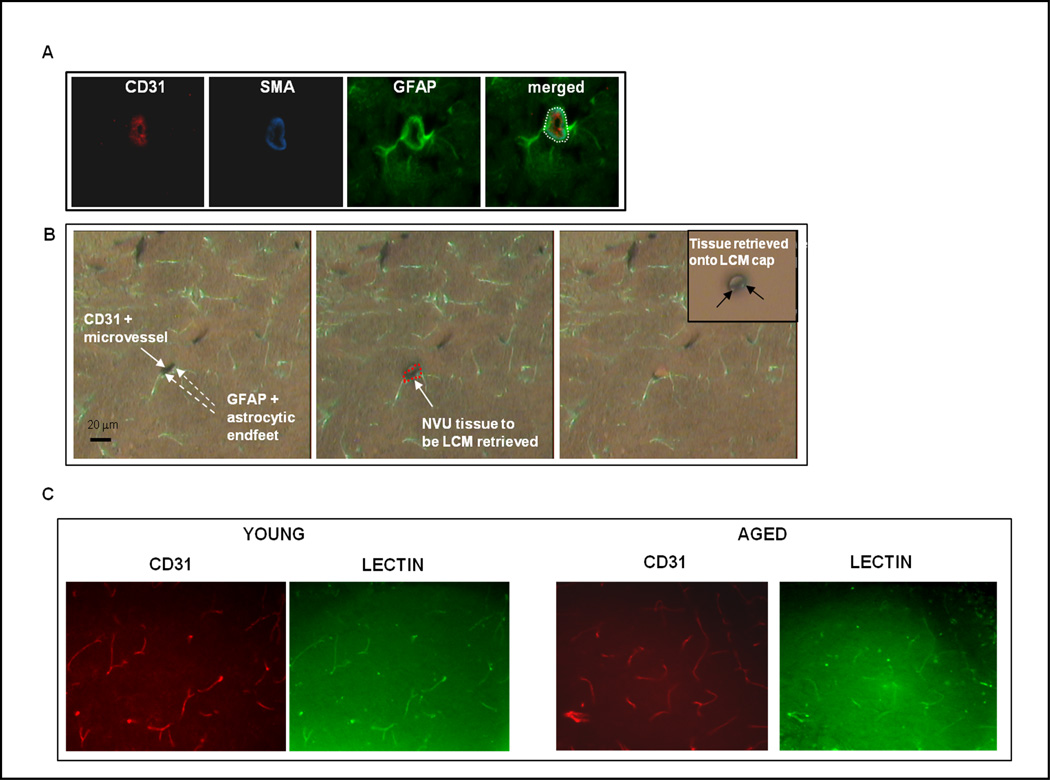

The NVU and its retrieval by immuno-LCM are shown in Fig. 1. Fig. 1A shows a larger diameter microvessel in cross-section so as to present NVU components in perspective. Fig. 1B shows typical capillary NVU fragments that were captured. Fig. 1C reveals there was no significant difference in percentage of patent microvessels in young vs. aged brain. Specifically, the Manders R coefficient of co-localization (Manders, et al., 1992) of perfused (lectin stained) and total (CD31 immunostained) microvessels was not statistically different in young (R= 0.832 ±0.048) vs. aged (R=0.899 ±0.058) mice. Thus, immuno-LCM would not tend to sample more occluded vessels in aged subjects. Suppl. Fig. 1 shows triple staining used to highlight the hippocampus for immuno-LCM.

Figure 1. The NVU can be targeted by immuno-LCM.

A, Components of the NVU. A coronal section of cortex was triple-stained with antibodies to CD31 to highlight brain microvascular endothelial cells, α-SMA (alpha smooth muscle actin) to mark pericytes/smooth muscle cells, and GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) to identify astrocyte foot-processes). Neuronal processes, not indicated here, are enmeshed with those of astrocytes. The - - - circle (white) encloses the NVU, the target material captured using immuno-LCM. B, Capture of NVU tissue. Left panel, Section showing CD31+ (dark brown) microvessel and surrounding GFAP+ (green) astrocyte foot-processes. Central panel, Same section with LCM “shot” over the NVU tissue (outlined in red). Right panel, Section post-LCM, showing the missing microvessel that was captured, and parenchyma left intact. Inset of right panel, Captured microvessel with closely apposed astrocyte foot-processes; i.e., NVU, on the LCM cap. C, Cerebral microvascular patency is similar in young vs. aged brain. Following labeling of patent vessels with i.v. injected FITC-lectin (green), young/aged brain cortical sections were immunostained for CD31 (red) to mark all endothelial cells. Quantitative analysis of co-localization of lectin-stained (green) and CD31+ (red) vessels was performed using the ImageJ 1.44 co-localization analysis (intensity correlation) plugin and revealed no age-related change in vessel patency.

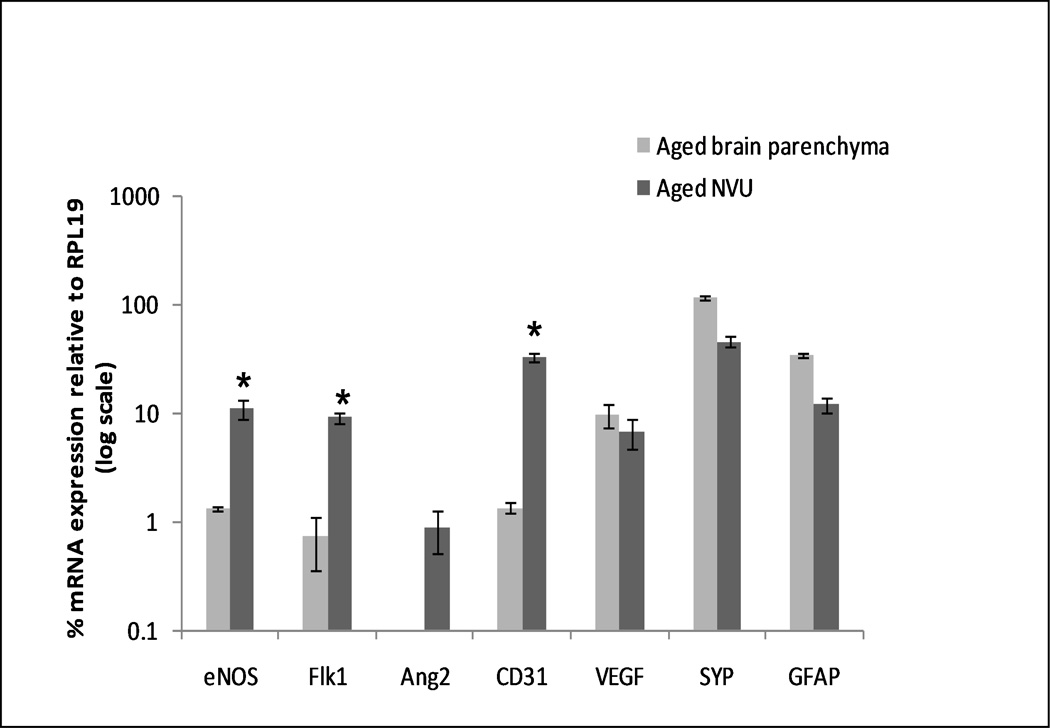

Immuno-LCM/qRT-PCR demonstrated that genes predominantly expressed by vascular endothelium, e.g., Flk1 (aka VEGFR-2/KDL), eNOS and CD31, were more highly expressed by NVU tissue compared to parenchymal tissue (Fig. 2). Detection of genes encoding GFAP (glial fibrillary acidic protein) and SYP (synaptophysin) - proteins concentrated at astrocyte end-feet and neuron terminals, respectively, contacting brain microvessels – additionally underscores these NVU components were effectively retrieved by LCM. Of further significance, Ang2 – a prominent angiogenesis associated gene (Thurston, 2003) – was not detected in brain parenchyma but was identified in NVU tissue. Hence, immuno-LCM/qRT-PCR of the NVU is a highly sensitive means to get a snapshot of angiogenic potential.

Figure 2. Immuno-LCM/qRT-PCR of NVU reveals enriched expression of angiogenesis-associated genes.

The graph contrasts gene expression in brain parenchymal vs. NVU tissue. Samples of either parenchymal (random LCM shots) or “targeted” NVU tissue were obtained by immuno-LCM from aged brain cortex, and processed for RNA profiling by qRT-PCR. Expression of genes is plotted as % relative to the housekeeping gene RPL19 ± S.E. (in log scale). Angiogenic genes show higher expression levels in the NVU. *p < 0.01, students two-tailed t-test.

3.2 Brain regional angiogenic potential in young vs. aged mice

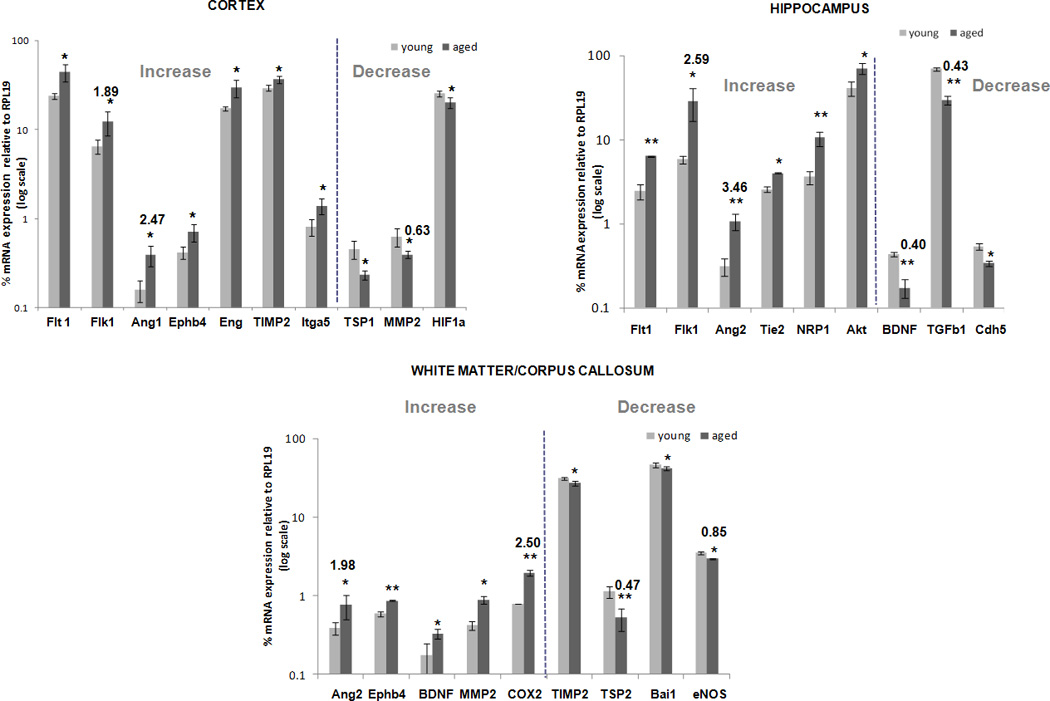

Immuno-LCM/qRT-PCR was used to assay expression of thirty-two angiogenesis-associated genes in cortex, hippocampus and anterior corpus callosum/white matter – in young vs. aged mice. The list of genes probed (Suppl. Table 1) was compiled by mining the literature for relevant angiogenesis-associated genes (Carmeliet, 2000; Carmeliet and Jain, 2000; Fan and Yang, 2007; Kermani and Hempstead, 2007; Peale and Gerritsen, 2001; Vikkula, et al., 2001), and is categorized into five groups: growth factors, secreted proteins and receptors; proteases, inhibitors and other matrix proteins; adhesion molecules; chemokines and cytokines; transcription factors and others. It is not meant to represent the entire angiome, but rather an illustrative subset of the contributing categories. Fig. 3 depicts those angiogenesis-associated genes whose constitutive expression was significantly altered when comparing young vs. aged mice. Notably, assemblies of genes showed age-related altered expression, and these differed depending on brain region.

Figure 3. Changes in brain regional expression of angiogenesis-associated genes in young vs. aged mice.

Relative mRNA expression values of the thirty-two angiogenesis-associated genes listed in Suppl. Table 1 were determined in NVU tissue from young and aged brain regions using immuno-LCM/qRT-PCR. Only those genes that differed significantly between both age groups, in cortex, hippocampus, and white matter/corpus callosum, are depicted. RNA values are presented as mean percent expression relative to RPL19 (+ SEM) in log scale. * p < 0.05, ** p < 0.005, students t-test.

In the cortex, ten genes displayed a significant difference with respect to age. Specifically, HIF1a, MMP2 and TSP1 decreased in expression in the aged cortex, while Flk1, Flt1, Ang1 TIMP2, Ephb4, Itga5 and Eng increased with age. In the hippocampus, aging was associated with significantly altered expression in nine of the genes analyzed. BDNF, Cdh5 and Tgfb1 decreased in expression with age, while Flk1, Flt1, Ang2, Nrp1, Tie2 and Akt increased. And in the corpus callosum/white matter, yet another pattern emerged. Expression of Ang2, BDNF, Ephb4, MMP2 and COX2 increased, while that of TSP2, Bai1, TIMP2 and eNOS decreased.

Complete analysis of all genes probed in the three regions is summarized in Suppl. Table 2. In addition to individual gene changes, a point to emphasize is that the impact of aging was not constant across regions. This might imply brain region-specific adaption of angiogenic potential to the aging process. Of additional note, expression of VEGF - widely recognized to be among the preeminent pro-angiogenic molecules (Ferrara, 2009; Patan, 2004) - was unaltered in expression at the NVU within all three brain regions of aged subjects.

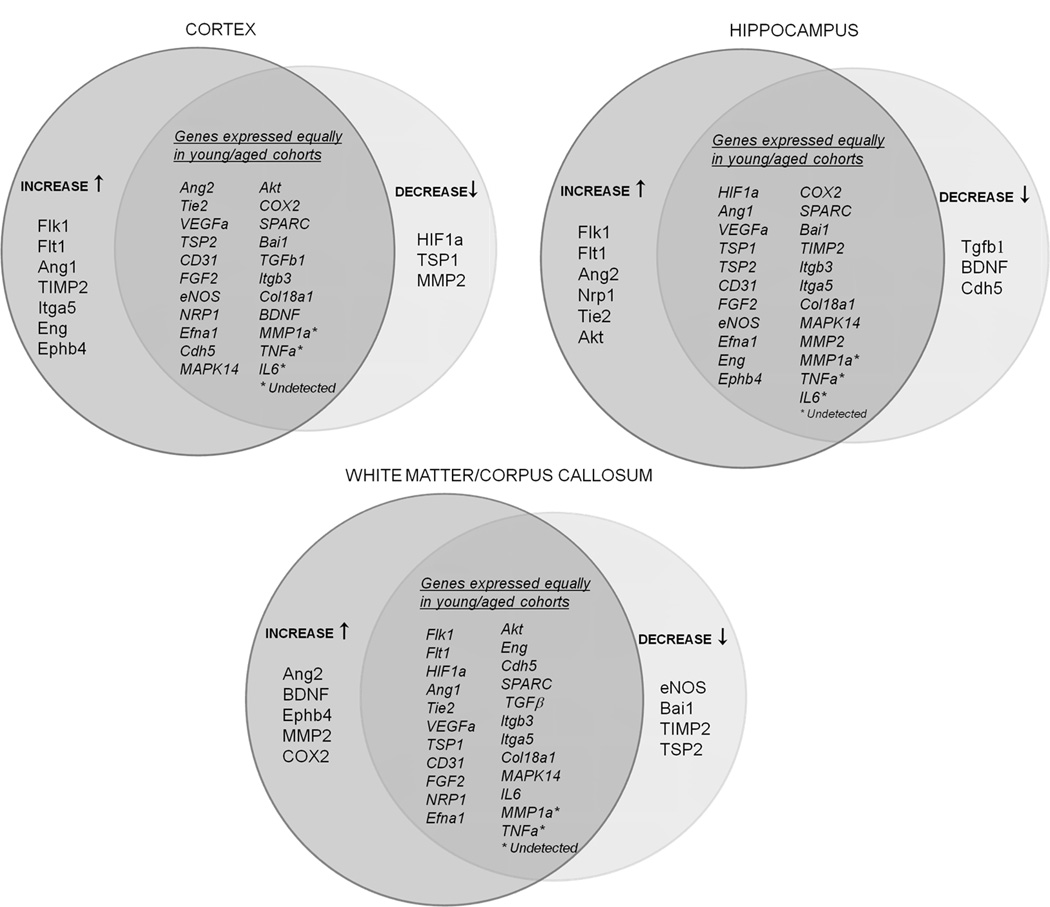

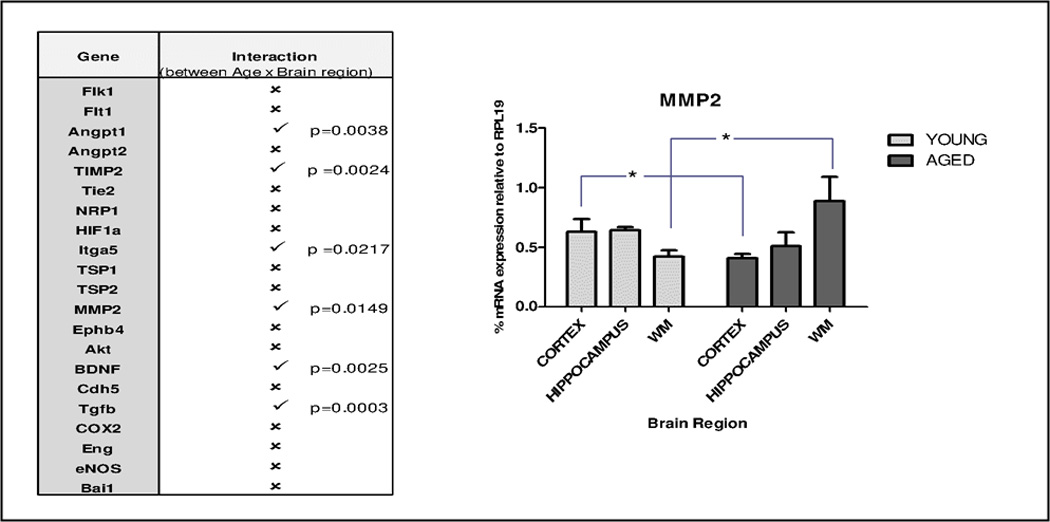

Venn diagrams (Fig. 4A) illustrate the distinct age-related trends in gene expression patterns displayed by the three brain regions. To confirm these patterns were regionally dependent, statistical interaction between age and brain region was determined. Specifically, 2-way ANOVA was performed on expression values of those genes that showed a significant difference with age in at least one brain region (twenty-one genes in total). Expression of six of these genes (Ang1, TIMP2, Itga5, MMP2, BDNF and Tgfb1) indicated positive interaction between the effect of age and brain region (Fig 4B). For example, aging was associated with decreased MMP2 expression in cortex but increased expression in white matter.

Figure 4. Relationships between age and brain region in expression of angiogenesis-associated genes.

A, Venn diagrams displaying relative expression patterns of angiogenesis-associated genes in different regions of young vs. aged brain. Separated, are those genes that decreased (↓) or increased (↑) with aging; genes expressed equally in young and aged cohorts are depicted in the intersection. B, Interactive effects of age and brain region were determined by two-way ANOVA on those angiogenesis-associated genes that showed a significant difference with age in at least any one brain region (21 genes). Six genes exhibited positive interaction between age and brain region and are denoted by (✓); the remaining fifteen genes showed no significant interaction, and are labeled by (✗). Matrix metalloproteinase A (MMP2) expression pattern across brain regions in young versus aged mice NVU, is graphed, * p < 0.05.

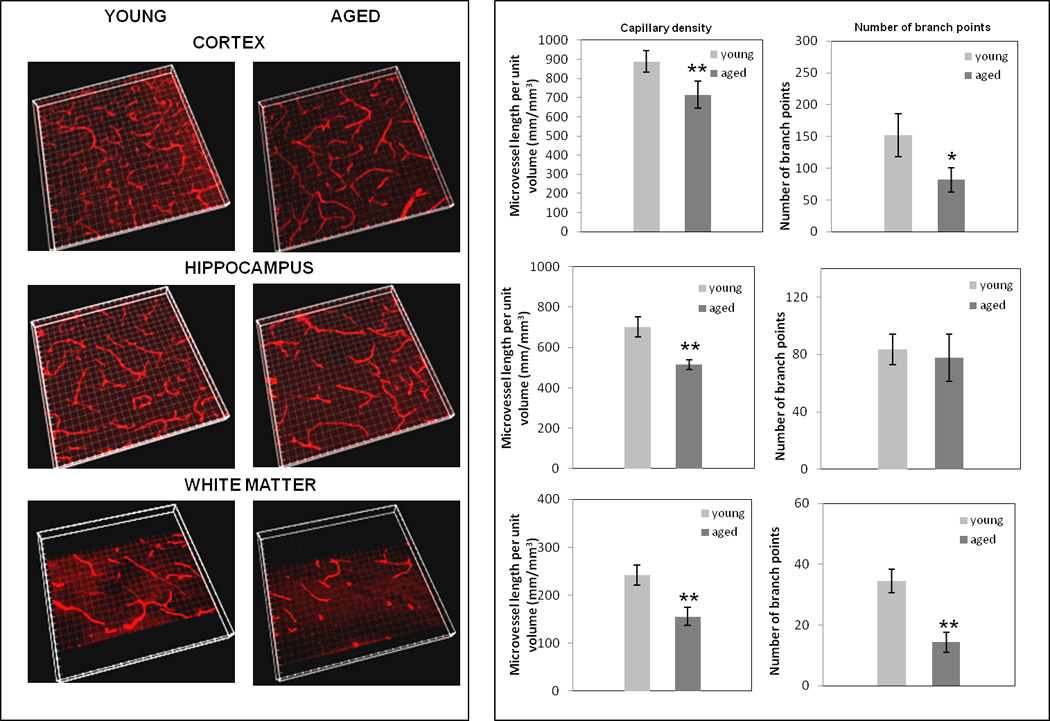

3.3 Regional brain microvessel density/branching in young vs. aged mice

To gauge if aging is also associated with distinctive regional changes in brain capillary density/branching, a detailed 3-D analysis was performed. Fig. 5 reveals significant capillary loss with aging in all three regions, with severity varying from region to region: cortex (19.26 ± 6.7%), hippocampus (26.38 ± 5.63%) and corpus callosum/white matter (34.5 ± 10.86%). Aged cortex and corpus callosum/white matter also showed reduced capillary branch points, while the hippocampus was spared this effect.

Figure 5. Changes in brain regional capillary density and branching in young vs. aged mice.

Sections (50 µm) of cortex, hippocampus and white matter/corpus-callosum were stained with anti-CD31 antibody and, following confocal microscopy and volume rendering of z stacks (left panel), capillary density (capillary length/unit volume) and branching were assessed. * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.005.

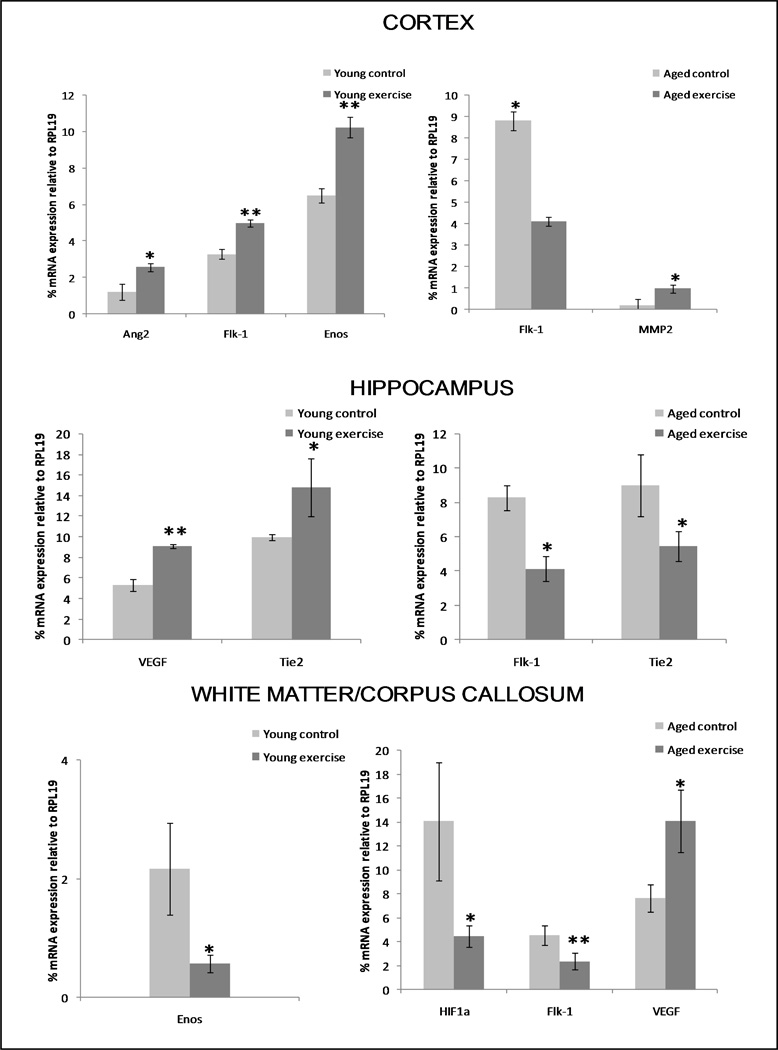

3.4 Impact of physical exercise on brain regional angiogenic potential and capillary density/branching in young vs. aged mice

To further investigate the interdependence of age and brain region, studies were carried out to determine if age-related changes in angiogenic potential and capillary density/branching could be reversed by physical exercise, and whether the extent and/or quality of such reversion was region-specific. Specifically, young and aged mice underwent a four-week treadmill training regimen and then immuno-LCM/qRT-PCR was used to profile a subset of genes (from Suppl. Table 1) shown to respond to physical exercise: Ang2, VEGF, Flk1, Tie2, CD31, TSP2, MMP2, HIF1a and eNOS (Ding, et al., 2006; Hu, et al., 2010; Kivela, et al., 2008; Laufs, et al., 2004; Leosco, et al., 2007; Timmons, et al., 2005). Fig. 6 clearly indicates exercise effects depended on age and brain region. In the aged cortex, exercise decreased expression of Flk1 and increased that of MMP2 - thus reversing aging trends - while in the young cortex it increased expression of Flk1, Ang2 and eNOS. In the aged hippocampus, exercise likewise reversed aging trends by decreasing Flk1 and Tie2 mRNA, while in the young hippocampus exercise caused increased VEGF and Tie2 expression. In the aged corpus callosum/white matter, exercise decreased expression of HIF1 and Flk1 and increased VEGF levels, while young cohorts displayed decreased eNOS levels with exercise in this region. Regional NVU expression of the entire set of exercise-responsive genes analyzed is shown in Suppl. Table 3.

Figure 6. Effect of physical exercise on expression of brain regional angiogenesis-associated genes in young vs. aged mice.

Mice were subject to a treadmill regimen, and thereafter immuno-LCM/qRT-PCR analysis was performed to gauge regional NVU expression of a subset of angiogenesis-associated genes (from Suppl. Table 1) known to respond to physical exercise. Control (unexercised) groups were used for each age group. Depicted are only those genes in young and aged cohorts that were influenced significantly by exercise (compared to unexercised controls). * p < 0.05 and ** p < 0.005.

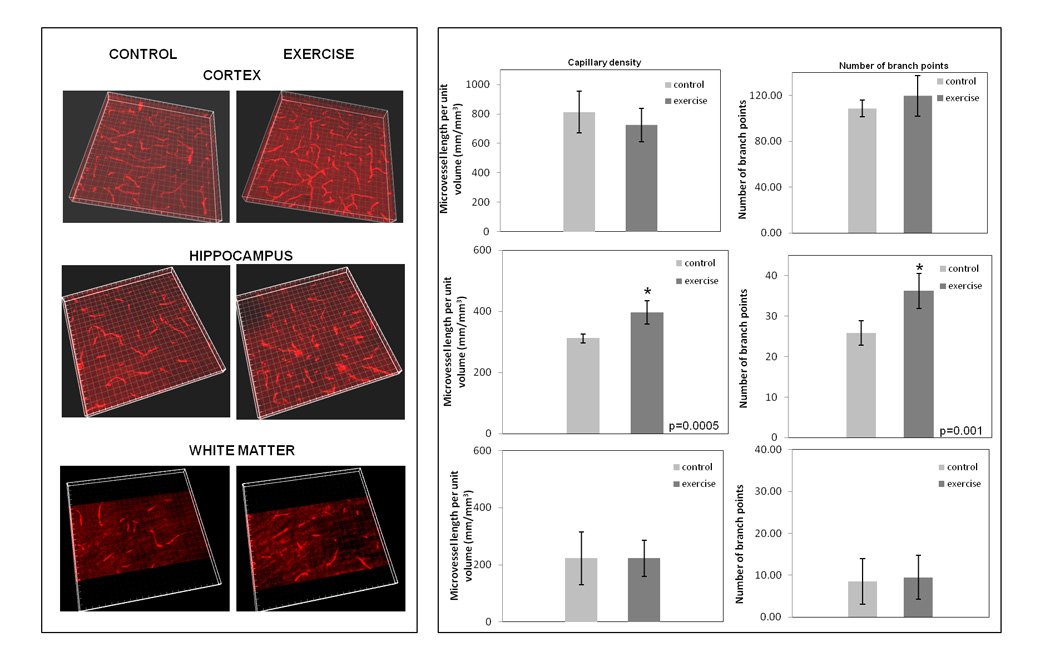

Aside from reversing some age-associated gene trends, physical exercise also positively impacted brain capillary density and branching, and did so in a region-dependent way. As indicated in Fig. 7, neither the aged cortex nor white matter showed changes in either vascular parameter as a result of exercise training. However, exercise stimulated both capillary density (33.5 ± 5.36%) and branching in the aged hippocampus.

Figure 7. Effects of physical exercise on regional brain capillary density and branching in aged mice.

Exercised mice underwent forced treadmill running for 30 min/day, for four weeks. Thereafter, brain sections (50 µm thickness) of cortex, hippocampus and white matter/corpus-callosum were stained with anti-CD31 antibody and capillary density and branching assessed as in Figure 5. Three-dimensional volume rendering of z stacks (left panel), and microvessel density and branching (right panel).

3.5 Angiogenic potential in response to whole-body hypoxia in young vs. aged mice

Lastly, studies were performed to get a better sense of the broader impact of aging on a collective of angiogenesis-associated genes previously shown to be responsive to hypoxia: VEGF, Flk1, Flt1, BDNF, HIF1a, eNOS, Akt, COX2 and CD31 (LaManna, et al., 2006; Madri, 2009; Ward, et al., 2007; Zhang, et al., 2009). Recent reports have indicated aging is associated with attenuated or delayed angiogenic response in the brain to chronic mild hypoxia, specific deficits being diminished stimulation in pro-angiogenic gene expression and/or retarded microvessel growth (Benderro and Lamanna, 2011; Ingraham, et al., 2008; Ndubuizu, et al., 2009; Ndubuizu, et al., 2010). As prior studies focused on a few select genes – primarily VEGF and its upstream regulator HIF1a (Benderro and Lamanna, 2011; Ndubuizu, et al., 2009; Ndubuizu, et al., 2010) – the intent here was to investigate whether a wider spectrum of other angiogenesis-associated genes, including those not regulated by HIF-a, were also hypo-responsive in aged brain. Of the nine genes analyzed in the cortex only, just two showed significantly altered expression at the NVU in response to whole-body, normobaric hypoxia for eight days (Suppl. Fig. 2). Moreover, while hypoxia caused a 5.1-fold increase in expression of HIF1a and a 2.6-fold decrease in Flk1 level in young mice, aged cohorts evidenced no change in either gene.

4.0 Discussion

4.1 Brain regional angiogenic potential in young vs. aged mice

LCM-qRT-PCR proved a highly effective tool to concentrate analysis of angiogenesis-associated genes at the level of the NVU and, accordingly, highlight age-related gene changes in the brain that are more likely to reflect vascular rather than neural status. The technique further uniquely enabled analysis in regional domains. Overall, aging profoundly altered expression of multiple angiogenesis-associated genes – though no preeminent gene was consistently affected across all brain regions. Instead, different ‘assemblies’ of these genes were affected in a region-dependent way. These findings align with studies on neovascularization of subcutaneously implanted polyvinyl alcohol sponges in young vs. aged mice (Koike, et al., 2003; Sadoun and Reed, 2003), which revealed multiple gene impairments in peripheral angiogenesis in aged subjects. That different gene assemblies were altered in different brain regions in the present study may imply that the same “physiologic endpoint” – reduced angiogenic potential – can be achieved through diverse manipulation of multiple angiogenesis-associated genes (Menon, et al., 2011), and that brain region is a decisive factor in the gene selection process. Such regional control over angiogenic potential is consistent with both asymmetrical brain aging (Berchtold et al., 2008) and endothelial heterogeneity (Aird, 2008; Chi, et al., 2003; Miike, et al., 2008).

As to specific gene changes observed, in aged cortex coordinated elevation in TIMP2 (an inhibitor of matrix metalloprotease MMP2) and reduction of MMP2 and HIF1a (both pro-angiogenic) suggests diminished angiogenic potential with age. These findings agree with those of Koike et al., (2003) who reported elevated levels of TIMP2 and diminished MMP2 in aged endothelial cells grown in vitro in collagen gels. Interestingly, reduced HIF1a expression has also been reported in skin wounds of aged vs. young mice suffering diabetes (Liu, et al., 2008), a condition known to be a risk factor for age-related cerebrovascular disease (Kalaria, 2010). The heightened level of alpha 5 integrin Itga5 mRNA detected in aged cortex also supports the work of Lu et al. (2004), who described a similar enhancement during transcriptional profiling of aged human frontal cortex, and may reveal action by age-associated advanced glycation endproducts (Molinari, et al., 2008). Increased expression of Flk1, Flt1 and Ang1 (the latter, a Tie2 ligand responsible for recruiting pericytes) at the NVU of aged cortex might further reflect compensatory changes to heighten VEGF responsiveness and stabilize aging cortical capillaries, respectively. Indeed, widespread compensatory mechanisms to dampen aging effects on the brain have been reported (Berchtold, et al., 2008). Our finding of increased expression of Ang2 in the aged hippocampus in the absence of a corresponding stimulated expression of VEGF could indicate a potential destabilization of microvessels (Maisonpierre, et al., 1997) – a status that may be additionally fostered by the reduced expression of pro-angiogenic BDNF also observed in this region. And the particular gene changes noted in the corpus callosum/white matter may reflect that this region is subject to age-related stress related to oxygen deprivation. Specifically, elevated expression of Ang2 and Cox2 noted at the NVU replicated that previously observed in cultured BMEC subject to hypoxia (Pichiule, et al., 2004). This could signify aging white matter in humans is especially sensitive to hypoxic insult –- possibly from chronic hypoperfusion (Fernando, et al., 2006). In this regard, the elevated MMP2 expression in aged corpus callosum/white matter also observed here, has similarly been described in this region following chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in rodents (Nakaji, et al., 2006). The reduced expression of pro-angiogenic eNOS at the NVU could further lend towards aberrant angiogenesis in the corpus callosum/white matter during normal aging, as haplotypes of this gene are associated with increased risk of small-vessel disease (Hassan, et al., 2004).

That VEGF expression at the NVU remained unaltered with age in all three brain regions is particularly noteworthy, given the widespread importance afforded to this factor regarding vessel growth. However, Ndubuizu et al. (2009) also reported no significant change in basal VEGF message with age in rat brain cortex, and squamous cell carcinoma tumors from young vs. aged mice displayed similar VEGF mRNA levels (Bojovic and Crowe, 2010). VEGF expression might be altered with aging in discrete brain regions not examined here – e.g., the substantia nigra pars compacta (Villar-Cheda, et al., 2009) – and/or detected age-related changes in VEGF gene activity may correspond more so to other neural cell roles (e.g., neuroprotective/neurogenic) rather than angiogenesis. It is tempting to speculate that, in the absence of concurrent elevation of VEGF, the noted age-related increase in hippocampal expression of Ang2 (the natural antagonist for Ang1) might facilitate vessel destabilization and regression, and muted cerebral angiogenesis during normal aging.

4.2 Regional brain microvessel density/branching in young vs. aged mice

Age-related microvessel loss also occurred in all regions and was highly region-dependent, complementing the recent finding that “healthy” human aging was associated with an anatomical location-dependent microvessel dropout (rarefaction), as visualized by magnetic resonance angiography (Bullitt, et al., 2010). The greatest loss occurred in the corpus callosum/white matter, which, consistent with previous findings (Klein, et al., 1986), demonstrated the lowest capillary density of all regions irrespective of age. To the best of our knowledge, our report is the first to correlate age-related changes in cerebral angiogenic potential with capillary rarefaction in white matter of other than human brain, and is in strong agreement with the significant loss of white matter capillaries recently described in the aged rat (Shao, et al. 2010). Both the density and gene changes noted carry particular clinical relevance as it has been suggested that age-related microvessel dropout in white matter stems from endothelial dysfunction and is causally related to leukoaraiosis (Brown and Thore, 2011) – a term referring to common neuroradiological findings on CT and MR scans (white matter “hyperintensities”) in elderly people and associated with cognitive decline, gait disturbance, urinary incontinence and depression (Zeevi, et al., 2010). Given its inherent low capillary density, the corpus callosum/white matter might be uniquely predisposed toward age-related microvessel disease (Pantoni, 2002).

There is no clear consensus as to the effect of aging on cerebral capillary density (Riddle, et al., 2003). Recently, other laboratories failed to note an age-related reduction in microvessel density in the brain regions studied here (Ndubuizu, et al., 2010), a disparity that could reflect the significant methodological differences amongst the studies. Use of different endothelial markers having variable expression along the microvascular tree and/or employing different size parameters to distinguish microvessels could potentially prejudice inclusion or exclusion of specific microvessel segments, e.g., capillaries, venules and/or arterioles (Ge, et al., 2005), thus giving rise to different vascular density estimates. In the present approach, all microvessels were stained with equal intensity (Kinnecom and Pachter, 2005; Macdonald, et al., 2008; Macdonald, et al., 2010; Murugesan, et al., 2011) but only those < 10 µm in diameter; i.e., capillaries, were quantified. Analyzing microvessels in 2-D vs. 3-D could be a factor as well. Similar to the unbiased stereological analysis of Shao et al., (2010), the confocal 3-D rendering approach used here, in which total capillary length in thick sections was determined, compensated for age-related changes in brain volume.

While this report focused on vascular phenomena such as angiogenesis and capillary density, the aging effects observed could also relate decisively to neuronal health. According to the vascular hypothesis of neurodegeneration put forth by Zlokovic (2010), vascular damage at the NVU could take a bifurcating path: causing reduced blood perfusion of the brain and hypoxia from one end, and blood-brain barrier (BBB) dysfunction from the other. In turn, both insults could cause secondary neuronal injury that prompts neurodegenerative changes. In line with this argument, normal aging is associated with progressive loss of cerebral collateral number and diameter (Faber, et al., 2011), as well as a compromise in the BBB (Farrall and Wardlaw, 2009; Zeevi, et al., 2010) due partially to decreased activity of efflux pumps (e.g., P-glycoprotein) and carrier-mediated transporters (e.g., glucose, choline and amino acid transporters). This deficit in the BBB could possibly allow toxic serum constituents to accrue in the brain parenchyma and heighten neuronal vulnerability. Such vulnerability may indeed be reflected by the findings of Lu et al. (2004), who described significant age-related downregulation of genes that play integral roles in synaptic function and plasticity in the human frontal cortex.

4.3 Physical exercise and the angiogenic response in aged brain

As regards the effects of exercise on gene expression, reversal of certain age-associated trends (e.g., Flk1, MMP2 in cortex; and Flk1, Tie2 in hippocampus) might intimate that physical exercise regimens “prime” certain brain regions to mount a more robust angiogenic response to vascular challenge, thereby mitigating age-related deficits in angiogenic adaptation. Supporting this concept, Iemitsu et al. 2006 reported physical exercise training reversed age-associated trends in both Flk1 mRNA and vascularity in the heart.

Again highlighting the nexus of aging, brain region and angiogenesis, physical exercise selectively increased capillary density and branching (the latter possibly representing neovessel sprouting) only in the aged hippocampus. Notably, a positive impact of exercise on endothelial cell proliferation in the adult rat hippocampus has been reported (Ekstrand, et al., 2008), suggesting beneficial effects of motor activity are not confined to motor regions of the brain. Physical exercise was also shown to selectively increase hippocampal cerebral blood volume in adult mice and humans (Pereira, et al., 2007). Increased cognition – a domain of the hippocampus – has also been associated with increased vessel density and neurogenesis in young adult mouse hippocampus after physical exercise, (Clark, et al., 2009). Further, a positive relationship between cognition and physical exercise has been confirmed by epidemiological studies (Lista and Sorrentino, 2010). In keeping with the regionalized effect of physical exercise, it was determined that cerebrovascular patterns of aerobically active healthy aged subjects appeared “younger” than age-matched aerobically inactive cohorts – but only in select brain areas (Bullitt, et al., 2009). While Ding, et al., (2006) noted that a similar treadmill paradigm as used here modified microvasculature in the motor cortex of aged rats, we noted no such effect. Though the nature of this disagreement is unclear, it may also relate to different methods used to quantify capillary density and/or species differences. Perhaps an elongated or otherwise varied exercise schedule may impart broader therapeutic effect across species. Indeed, Anderson, et al., (2010) have recently argued physical exercise can provide multiple levels of metabolic support necessary for generally maintaining optimal neuronal function, though effects may still show a brain regional preference. Physical exercise training might further be complemented by cognitive exercise training. In this regard, intellectual stimulation through environmental enrichment has been shown to positively impact regional angiogenesis in adult rat brain (Ekstrand, et al., 2008). Physical exercise might additionally lend the aging brain other vascular benefits aside from angiogenesis. For example, while aging is associated with dysfunctional endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS)/NO signaling that contributes to impaired remodeling efforts (Yang, et al., 2009; Zhang, et al., 2005), physical exercise has been reported to confer vasoprotection by augmenting NO bioavailability and restoring endothelium dependent vasodilation in healthy elderly subjects (DeSouza, et al., 2000; Taddei, et al., 2000).

Significantly, the exercise-induced reversals noted here occurred despite the backdrop of an attenuated angiogenic response to hypoxia associated with normal aging. Indeed, a muted and delayed up-regulation of hypoxia inducible genes HIF-1 and VEGF in the cortex of both aged rats and mice has been reported (Benderro and Lamanna, 2011; Ndubuizu, et al., 2010), as has reduced capillary angiogenesis in the hippocampus of aged rats (Ingraham, et al., 2008), following chronic, whole-body hypoxia. Our results focusing on the NVU are consistent with and extend these findings, and further highlight physical exercise can exert positive effects on angiogenic potential and capillary density regardless of the handicap imposed by aging on microvascular plasticity. In what might reflect a parallel therapeutic effect on the hippocampus, housing enrichment – which included voluntary physical exercise – has recently been shown to reverse age-associated cognitive impairments (Obiang, et al., 2011).

Collectively, our findings reinforce recent views that angiogenesis differs considerably in young vs. aged subjects, and that even within the aged population, aspects of angiogenesis may differ widely between peripheral and CNS microvascular beds (Petcu, et al., 2010; Sonntag, et al., 2007). Results further indicate age-related effects on angiogenesis are regionally dependent, underscoring the growing appreciation that the brain ages asymmetrically at the gene and anatomic levels (Berchtold, et al., 2008; Mora, et al., 2007). Finally, as physical exercise corrected some age-related deviations in angiogenic potential and capillary density, and angiogenesis and neurogenesis are tightly coupled (Yang, et al., 2011), activity-based means to stimulate cerebral angiogenesis might be of significant therapeutic value in maintaining brain health with age. Further detailed regional analysis of brain microvasculature is critical for identifying and accurately associating cerebrovascular alterations with age-associated neurological deficits (Grammas, 2011; Kalaria, 2010), and could well contribute to a formula for maintaining brain health in the elderly.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by grants RO-1-MH54718 and R21-NS057241 from the National Institutes of Health, grant PP-1215 from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, and grant 2011-0143 from the Connecticut Dept. of Public Health to J.S.P; grants PO1- NS00344738 and RO1-HL51018 to J.A.M.; and American Heart Association pre-doctoral fellowship award 0815733D to N.M. The authors would like to extend our gratitude and thanks to Drs. George Kuchel and Qing Zhu for helpful discussions and provision of aged mice, and Dr. Bruce Liang for providing us use of the mouse treadmill apparatus. The authors also thank Ms. Yen Lemire for assistance with the microvessel patency study, as well as Dr. Shujun Ge, Ms. Sonali Bishnoi and Ms. Palak Shelat for assistance with the hypoxia study.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Disclosure statement

The authors have no actual or potential conflicts of interest. All animal treatments were reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and were in accordance with guidelines stipulated by the Animal Care and Use Guidelines of the University of Connecticut Health Center and the Yale University Animal Care Committee.

References

- Aird WC. Endothelium in health and disease. Pharmacol Rep. 2008;60(1):139–143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson BJ, Greenwood SJ, McCloskey D. Exercise as an intervention for the age-related decline in neural metabolic support. Front Aging Neurosci. 2010 Aug 13;2:pii: 30. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2010.00030. 2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arai K, Jin G, Navaratna D, Lo EH. Brain angiogenesis in developmental and pathological processes: neurovascular injury and angiogenic recovery after stroke. Febs J. 2009;276(17):4644–4652. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2009.07176.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranha AM, Zhang Z, Neiva KG, Costa CA, Hebling J, Nor JE. Hypoxia enhances the angiogenic potential of human dental pulp cells. J Endod. 2010;36(10):1633–1637. doi: 10.1016/j.joen.2010.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benderro GF, Lamanna JC. Hypoxia-induced angiogenesis is delayed in aging mouse brain. Brain Res. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berchtold NC, Cribbs DH, Coleman PD, Rogers J, Head E, Kim R, Beach T, Miller C, Troncoso J, Trojanowski JQ, Zielke HR, Cotman CW. Gene expression changes in the course of normal brain aging are sexually dimorphic. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(40):15605–15610. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0806883105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black JE, Polinsky M, Greenough WT. Progressive failure of cerebral angiogenesis supporting neural plasticity in aging rats. Neurobiol Aging. 1989;10(4):353–358. doi: 10.1016/0197-4580(89)90048-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bojovic B, Crowe DL. Chronologic aging decreases tumor angiogenesis and metastasis in a mouse model of head and neck cancer. Int J Oncol. 2010;36(3):715–723. doi: 10.3892/ijo_00000547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown WR, Thore CR. Review: cerebral microvascular pathology in ageing and neurodegeneration. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol. 2011;37(1):56–74. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2990.2010.01139.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullitt E, Rahman FN, Smith JK, Kim E, Zeng D, Katz LM, Marks BL. The effect of exercise on the cerebral vasculature of healthy aged subjects as visualized by MR angiography. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2009;30(10):1857–1863. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A1695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bullitt E, Zeng D, Mortamet B, Ghosh A, Aylward SR, Lin W, Marks BL, Smith K. The effects of healthy aging on intracerebral blood vessels visualized by magnetic resonance angiography. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31(2):290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. Mechanisms of angiogenesis and arteriogenesis. Nat Med. 2000;6(4):389–395. doi: 10.1038/74651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P. Angiogenesis in health and disease. Nat Med. 2003;9(6):653–660. doi: 10.1038/nm0603-653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407(6801):249–257. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chi JT, Chang HY, Haraldsen G, Jahnsen FL, Troyanskaya OG, Chang DS, Wang Z, Rockson SG, van de Rijn M, Botstein D, Brown PO. Endothelial cell diversity revealed by global expression profiling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100(19):10623–10628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1434429100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark PJ, Brzezinska WJ, Puchalski EK, Krone DA, Rhodes JS. Functional analysis of neurovascular adaptations to exercise in the dentate gyrus of young adult mice associated with cognitive gain. Hippocampus. 2009;19(10):937–950. doi: 10.1002/hipo.20543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeSouza CA, Shapiro LF, Clevenger CM, Dinenno FA, Monahan KD, Tanaka H, Seals DR. Regular aerobic exercise prevents and restores age-related declines in endothelium-dependent vasodilation in healthy men. Circulation. 2000;102(12):1351–1357. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.102.12.1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickie R, Bachoo RM, Rupnick MA, Dallabrida SM, Deloid GM, Lai J, Depinho RA, Rogers RA. Three-dimensional visualization of microvessel architecture of whole-mount tissue by confocal microscopy. Microvasc Res. 2006;72(1–2):20–26. doi: 10.1016/j.mvr.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding YH, Li J, Zhou Y, Rafols JA, Clark JC, Ding Y. Cerebral angiogenesis and expression of angiogenic factors in aging rats after exercise. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2006;3(1):15–23. doi: 10.2174/156720206775541787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dore-Duffy P, LaManna JC. Physiologic angiodynamics in the brain. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2007;9(9):1363–1371. doi: 10.1089/ars.2007.1713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ekstrand J, Hellsten J, Tingstrom A. Environmental enrichment, exercise and corticosterone affect endothelial cell proliferation in adult rat hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Neurosci Lett. 2008;442(3):203–207. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2008.06.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faber JE, Zhang H, Lassance-Soares RM, Prabhakar P, Najafi AH, Burnett MS, Epstein SE. Aging causes collateral rarefaction and increased severity of ischemic injury in multiple tissues. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2011;31(8):1748–1756. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.111.227314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y, Yang GY. Therapeutic angiogenesis for brain ischemia: a brief review. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2007;2(3):284–289. doi: 10.1007/s11481-007-9073-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farrall AJ, Wardlaw JM. Blood-brain barrier: ageing and microvascular disease--systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurobiol Aging. 2009;30(3):337–352. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernando MS, Simpson JE, Matthews F, Brayne C, Lewis CE, Barber R, Kalaria RN, Forster G, Esteves F, Wharton SB, Shaw PJ, O'Brien JT, Ince PG. White matter lesions in an unselected cohort of the elderly: molecular pathology suggests origin from chronic hypoperfusion injury. Stroke. 2006;37(6):1391–1398. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000221308.94473.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara N. VEGF-A: a critical regulator of blood vessel growth. Eur Cytokine Netw. 2009;20(4):158–163. doi: 10.1684/ecn.2009.0170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge S, Song L, Pachter JS. Where is the blood-brain barrier … really? J Neurosci Res. 2005;79(4):421–427. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George P, Keith BJ. The Mouse Brain in Sterotaxic Coordinates. 2nd Ed. Academic Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Grammas P. Neurovascular dysfunction, inflammation and endothelial activation: Implications for the pathogenesis of Alzheimer's disease. J Neuroinflammation. 2011;8:26. doi: 10.1186/1742-2094-8-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hassan A, Gormley K, O'Sullivan M, Knight J, Sham P, Vallance P, Bamford J, Markus H. Endothelial nitric oxide gene haplotypes and risk of cerebral small-vessel disease. Stroke. 2004;35(3):654–659. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000117238.75736.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins BT, Davis TP. The blood-brain barrier/neurovascular unit in health and disease. Pharmacol Rev. 2005;57(2):173–185. doi: 10.1124/pr.57.2.4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes K, Sprague S, Guo M, Davis W, Friedman A, Kumar A, Jimenez DF, Ding Y. Forced, not voluntary, exercise effectively induces neuroprotection in stroke. Acta Neuropathol. 2008;115(3):289–296. doi: 10.1007/s00401-008-0340-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hof PR, Bussiere T, Morrison JH. Neuropathology of the ageing brain in The Neuropathology of Dementia: Second Edition. 2004:113–127. [Google Scholar]

- Hu X, Zheng H, Yan T, Pan S, Fang J, Jiang R, Ma S. Physical exercise induces expression of CD31 and facilitates neural function recovery in rats with focal cerebral infarction. Neurol Res. 2010;32(4):397–402. doi: 10.1179/016164110X12670144526309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingraham JP, Forbes ME, Riddle DR, Sonntag WE. Aging reduces hypoxia-induced microvascular growth in the rodent hippocampus. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(1):12–20. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.1.12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaria RN. Vascular basis for brain degeneration: faltering controls and risk factors for dementia. Nutr Rev. 2010;68 Suppl 2:S74–S87. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00352.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kermani P, Hempstead B. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor: a newly described mediator of angiogenesis. Trends Cardiovasc Med. 2007;17(4):140–143. doi: 10.1016/j.tcm.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinnecom K, Pachter JS. Selective capture of endothelial and perivascular cells from brain microvessels using laser capture microdissection. Brain Res Brain Res Protoc. 2005;16(1–3):1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresprot.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kivela R, Silvennoinen M, Lehti M, Jalava S, Vihko V, Kainulainen H. Exercise-induced expression of angiogenic growth factors in skeletal muscle and in capillaries of healthy and diabetic mice. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2008;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1475-2840-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein B, Kuschinsky W, Schrock H, Vetterlein F. Interdependency of local capillary density, blood flow, and metabolism in rat brains. Am J Physiol. 1986;251(6 Pt 2):H1333–H1340. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1986.251.6.H1333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klement H, St Croix B, Milsom C, May L, Guo Q, Yu JL, Klement P, Rak J. Atherosclerosis and vascular aging as modifiers of tumor progression, angiogenesis, and responsiveness to therapy. Am J Pathol. 2007;171(4):1342–1351. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2007.070298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koike T, Vernon RB, Gooden MD, Sadoun E, Reed MJ. Inhibited angiogenesis in aging: a role for TIMP-2. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2003;58(9):B798–B805. doi: 10.1093/gerona/58.9.b798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar R, Yoneda J, Bucana CD, Fidler IJ. Regulation of distinct steps of angiogenesis by different angiogenic molecules. Int J Oncol. 1998;12(4):749–757. doi: 10.3892/ijo.12.4.749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaManna JC, Sun X, Ivy AD, Ward NL. Is cycloxygenase-2 (COX-2) a major component of the mechanism responsible for microvascular remodeling in the brain? Adv Exp Med Biol. 2006;578:297–303. doi: 10.1007/0-387-29540-2_47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laufs U, Werner N, Link A, Endres M, Wassmann S, Jurgens K, Miche E, Bohm M, Nickenig G. Physical training increases endothelial progenitor cells, inhibits neointima formation, and enhances angiogenesis. Circulation. 2004;109(2):220–226. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000109141.48980.37. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leosco D, Rengo G, Iaccarino G, Sanzari E, Golino L, De Lisa G, Zincarelli C, Fortunato F, Ciccarelli M, Cimini V, Altobelli GG, Piscione F, Galasso G, Trimarco B, Koch WJ, Rengo F. Prior exercise improves age-dependent vascular endothelial growth factor downregulation and angiogenesis responses to hind-limb ischemia in old rats. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2007;62(5):471–480. doi: 10.1093/gerona/62.5.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Welser JV, Dore-Duffy P, del Zoppo GJ, Lamanna JC, Milner R. In the hypoxic central nervous system, endothelial cell proliferation is followed by astrocyte activation, proliferation, and increased expression of the alpha 6 beta 4 integrin and dystroglycan. Glia. 2010;58(10):1157–1167. doi: 10.1002/glia.20995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q, Liu J, Michaud M, Schwartz ML, Madri JA. Strain differences in behavioral and cellular responses to perinatal hypoxia and relationships to neural stem cell survival and self-renewal: Modeling the neurovascular niche. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(5):2133–2146. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lista I, Sorrentino G. Biological mechanisms of physical activity in preventing cognitive decline. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2010;30(4):493–503. doi: 10.1007/s10571-009-9488-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu L, Marti GP, Wei X, Zhang X, Zhang H, Liu YV, Nastai M, Semenza GL, Harmon JW. Age-dependent impairment of HIF-1alpha expression in diabetic mice: Correction with electroporation-facilitated gene therapy increases wound healing, angiogenesis, and circulating angiogenic cells. J Cell Physiol. 2008;217(2):319–327. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lok J, Gupta P, Guo S, Kim WJ, Whalen MJ, van Leyen K, Lo EH. Cell-cell signaling in the neurovascular unit. Neurochem Res. 2007;32(12):2032–2045. doi: 10.1007/s11064-007-9342-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu T, Pan Y, Kao SY, Li C, Kohane I, Chan J, Yankner BA. Gene regulation and DNA damage in the ageing human brain. Nature. 2004;429(6994):883–891. doi: 10.1038/nature02661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald JA, Murugesan N, Pachter JS. Validation of immuno-laser capture microdissection coupled with quantitative RT-PCR to probe blood-brain barrier gene expression in situ. J Neurosci Methods. 2008;174(2):219–226. doi: 10.1016/j.jneumeth.2008.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald JA, Murugesan N, Pachter JS. Endothelial cell heterogeneity of blood-brain barrier gene expression along the cerebral microvasculature. J Neurosci Res. 2010;88(7):1457–1474. doi: 10.1002/jnr.22316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madri JA. Modeling the neurovascular niche: implications for recovery from CNS injury. J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;60 Suppl 4:95–104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maisonpierre PC, Suri C, Jones PF, Bartunkova S, Wiegand SJ, Radziejewski C, Compton D, McClain J, Aldrich TH, Papadopoulos N, Daly TJ, Davis S, Sato TN, Yancopoulos GD. Angiopoietin-2, a natural antagonist for Tie2 that disrupts in vivo angiogenesis. Science. 1997;277(5322):55–60. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5322.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manders EM, Verbeek FJ, Aten JA. Measurement of co-localization of objects in dual colour confocal images. Journal of microscopy. 1992;169(Pt 3):375–382. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.1993.tb03313.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mattson MP, Magnus T. Ageing and neuronal vulnerability. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2006;7(4):278–294. doi: 10.1038/nrn1886. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon S, Fessel J, West J. Microarray studies in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Int J Clin Pract Suppl. 2011;(169):19–28. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02604.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miike T, Shirahase H, Kanda M, Kunishiro K, Kurahashi K. Regional heterogeneity of substance P-induced endothelium-dependent contraction, relaxation, and -independent contraction in rabbit pulmonary arteries. Life Sci. 2008;83(23–24):810–814. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2008.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitschelen M, Yan H, Farley JA, Warrington JP, Han S, Herenu CB, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z, Bailey-Downs LC, Bass CE, Sonntag WE. Long-term deficiency of circulating and hippocampal insulin-like growth factor I induces depressive behavior in adult mice: a potential model of geriatric depression. Neuroscience. 2011;185:50–60. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molinari J, Ruszova E, Velebny V, Robert L. Effect of advanced glycation endproducts on gene expression profiles of human dermal fibroblasts. Biogerontology. 2008;9(3):177–182. doi: 10.1007/s10522-008-9129-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody DM, Thore CR, Anstrom JA, Challa VR, Langefeld CD, Brown WR. Quantification of afferent vessels shows reduced brain vascular density in subjects with leukoaraiosis. Radiology. 2004;233(3):883–890. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2333020981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mora F, Segovia G, del Arco A. Aging, plasticity and environmental enrichment: structural changes and neurotransmitter dynamics in several areas of the brain. Brain Res Rev. 2007;55(1):78–88. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2007.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugesan N, Macdonald JA, Lu Q, Wu SL, Hancock WS, Pachter JS. Analysis of mouse brain microvascular endothelium using laser capture microdissection coupled with proteomics. Methods Mol Biol. 2011;686:297–311. doi: 10.1007/978-1-60761-938-3_14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakaji K, Ihara M, Takahashi C, Itohara S, Noda M, Takahashi R, Tomimoto H. Matrix metalloproteinase-2 plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of white matter lesions after chronic cerebral hypoperfusion in rodents. Stroke. 2006;37(11):2816–2823. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000244808.17972.55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndubuizu OI, Chavez JC, LaManna JC. Increased prolyl 4-hydroxylase expression and differential regulation of hypoxia-inducible factors in the aged rat brain. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol. 2009;297(1):R158–R165. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.90829.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ndubuizu OI, Tsipis CP, Li A, LaManna JC. Hypoxia-inducible factor-1 (HIF-1)-independent microvascular angiogenesis in the aged rat brain. Brain Res. 2010;1366:101–109. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2010.09.064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obiang P, Maubert E, Bardou I, Nicole O, Launay S, Bezin L, Vivien D, Agin V. Enriched housing reverses age-associated impairment of cognitive functions and tPA-dependent maturation of BDNF. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2011;96(2):121–129. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2011.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pantoni L. Pathophysiology of age-related cerebral white matter changes. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2002;13 Suppl 2:7–10. doi: 10.1159/000049143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patan S. Vasculogenesis and angiogenesis. Cancer Treat Res. 2004;117:3–32. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8871-3_1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peale FV, Jr, Gerritsen ME. Gene profiling techniques and their application in angiogenesis and vascular development. J Pathol. 2001;195(1):7–19. doi: 10.1002/path.888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira AC, Huddleston DE, Brickman AM, Sosunov AA, Hen R, McKhann GM, Sloan R, Gage FH, Brown TR, Small SA. An in vivo correlate of exercise-induced neurogenesis in the adult dentate gyrus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104(13):5638–5643. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611721104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petcu EB, Smith RA, Miroiu RI, Opris MM. Angiogenesis in old-aged subjects after ischemic stroke: a cautionary note for investigators. J Angiogenes Res. 2010;2:26. doi: 10.1186/2040-2384-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pichiule P, Chavez JC, LaManna JC. Hypoxic regulation of angiopoietin-2 expression in endothelial cells. J Biol Chem. 2004;279(13):12171–12180. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M305146200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa-Wagner A, Pirici D, Petcu EB, Mogoanta L, Buga AM, Rosen CL, Leon R, Huber J. Pathophysiology of the vascular wall and its relevance for cerebrovascular disorders in aged rodents. Curr Neurovasc Res. 2010;7(3):251–267. doi: 10.2174/156720210792231813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed MJ, Edelberg JM. Impaired angiogenesis in the aged. Sci Aging Knowledge Environ. 2004;2004(7):pe7. doi: 10.1126/sageke.2004.7.pe7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riddle DR, Sonntag WE, Lichtenwalner RJ. Microvascular plasticity in aging. Ageing Res Rev. 2003;2(2):149–168. doi: 10.1016/s1568-1637(02)00064-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rivard A, Fabre JE, Silver M, Chen D, Murohara T, Kearney M, Magner M, Asahara T, Isner JM. Age-dependent impairment of angiogenesis. Circulation. 1999;99(1):111–120. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.99.1.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadoun E, Reed MJ. Impaired angiogenesis in aging is associated with alterations in vessel density, matrix composition, inflammatory response, and growth factor expression. J Histochem Cytochem. 2003;51(9):1119–1130. doi: 10.1177/002215540305100902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segura I, De Smet F, Hohensinner PJ, Ruiz de Almodovar C, Carmeliet P. The neurovascular link in health and disease: an update. Trends Mol Med. 2009;15(10):439–451. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao WH, Li C, Chen L, Qiu X, Zhang W, Huang CX, Xia L, Kong JM, Tang Y. Stereological investigation of age-related changes of the capillaries in white matter. Anat Rec (Hoboken) 2010;293(8):1400–1407. doi: 10.1002/ar.21184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skalak TC. Angiogenesis and microvascular remodeling: a brief history and future roadmap. Microcirculation. 2005;12(1):47–58. doi: 10.1080/10739680590895037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonntag WE, Eckman DM, Ingraham J, Riddle DR. Regulation of Cerebrovascular Aging. Chapter 12. CRC Press; 2007. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taddei S, Galetta F, Virdis A, Ghiadoni L, Salvetti G, Franzoni F, Giusti C, Salvetti A. Physical activity prevents age-related impairment in nitric oxide availability in elderly athletes. Circulation. 2000;101(25):2896–2901. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.25.2896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tam SJ, Watts RJ. Connecting vascular and nervous system development: angiogenesis and the blood-brain barrier. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2010;33:379–408. doi: 10.1146/annurev-neuro-060909-152829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thurston G. Role of Angiopoietins and Tie receptor tyrosine kinases in angiogenesis and lymphangiogenesis. Cell Tissue Res. 2003;314(1):61–68. doi: 10.1007/s00441-003-0749-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Timmons JA, Jansson E, Fischer H, Gustafsson T, Greenhaff PL, Ridden J, Rachman J, Sundberg CJ. Modulation of extracellular matrix genes reflects the magnitude of physiological adaptation to aerobic exercise training in humans. BMC Biol. 2005;3:19. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-3-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vikkula M, Boon LM, Mulliken JB. Molecular genetics of vascular malformations. Matrix Biol. 2001;20(5–6):327–335. doi: 10.1016/s0945-053x(01)00150-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Villar-Cheda B, Sousa-Ribeiro D, Rodriguez-Pallares J, Rodriguez-Perez AI, Guerra MJ, Labandeira-Garcia JL. Aging and sedentarism decrease vascularization and VEGF levels in the rat substantia nigra. Implications for Parkinson's disease. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2009;29(2):230–234. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2008.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward NL, Lamanna JC. The neurovascular unit and its growth factors: coordinated response in the vascular and nervous systems. Neurol Res. 2004;26(8):870–883. doi: 10.1179/016164104X3798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward NL, Moore E, Noon K, Spassil N, Keenan E, Ivanco TL, LaManna JC. Cerebral angiogenic factors, angiogenesis, and physiological response to chronic hypoxia differ among four commonly used mouse strains. J Appl Physiol. 2007;102(5):1927–1935. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00909.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ward R, Collins RL, Tanguay G, Miceli D. A quantitative study of cerebrovascular variation in inbred mice. J Anat. 1990;173:87–95. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wykrzykowska JJ, Bianchi C, Sellke FW. Impact of aging on the angiogenic potential of the myocardium: implications for angiogenic therapies with emphasis on sirtuin agonists. Recent Pat Cardiovasc Drug Discov. 2009;4(2):119–132. doi: 10.2174/157489009788452913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang XT, Bi YY, Feng DF. From the vascular microenvironment to neurogenesis. Brain Res Bull. 2011;84(1):1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2010.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang YM, Huang A, Kaley G, Sun D. eNOS uncoupling and endothelial dysfunction in aged vessels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2009;297(5):H1829–H1836. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00230.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacchigna S, Lambrechts D, Carmeliet P. Neurovascular signalling defects in neurodegeneration. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2008;9(3):169–181. doi: 10.1038/nrn2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeevi N, Pachter J, McCullough LD, Wolfson L, Kuchel GA. The blood-brain barrier: geriatric relevance of a critical brain-body interface. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010;58(9):1749–1757. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03011.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang EG, Smith SK, Charnock-Jones DS. Expression of CD105 (endoglin) in arteriolar endothelial cells of human endometrium throughout the menstrual cycle. Reproduction. 2002;124(5):703–711. doi: 10.1530/rep.0.1240703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Qu Y, Yang C, Tang J, Zhang X, Mao M, Mu D, Ferriero D. Signaling pathway involved in hypoxia-inducible factor-1alpha regulation in hypoxic-ischemic cortical neurons in vitro. Neurosci Lett. 2009;461(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2009.03.091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Zhang RL, Wang Y, Zhang C, Zhang ZG, Meng H, Chopp M. Functional recovery in aged and young rats after embolic stroke: treatment with a phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitor. Stroke. 2005;36(4):847–852. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000158923.19956.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Q, Kiosses WB, Liu J, Schimmel P. Tumor endothelial cell tube formation model for determining anti-angiogenic activity of a tRNA synthetase cytokine. Methods. 2008;44(2):190–195. doi: 10.1016/j.ymeth.2007.10.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zlokovic BV. Neurodegeneration and the neurovascular unit. Nat Med. 2010;16(12):1370–1371. doi: 10.1038/nm1210-1370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zoccoli G, Lucchi ML, Andreoli E, Lenzi P, Franzini C. Density of perfused brain capillaries in the aged rat during the wake-sleep cycle. Exp Brain Res. 2000;130(1):73–77. doi: 10.1007/s002219900219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.