Abstract

Objective

To estimate the risk for nodal metastasis in women with endometrial cancer based on uterine characteristics on pathology.

Methods

From a study of staging for uterine cancer, women were identified as low risk for nodal metastasis based on three specific criteria on final pathology reports: 1) less than 50% invasion; 2) tumor size less than 2 cm; and 3) well or moderately differentiated endometrioid histology. If the uterine specimen did not meet all three criteria, it was viewed as high risk for nodal metastasis.

Results

Nine hundred seventy-one women were included in this analysis. Approximately 40% (or 389/971) of patients in this study were found to be low risk with a rate of nodal metastasis of only 0.8% (3/389; exact 95% CI, 0.16%–2.2%). No statistical differences in median age, body mass index (BMI), race, performance status, missing clinical data, or open or minimally invasive techniques were found among the patients with and without nodal metastases. Patients with high-risk characteristics on their uterine specimens compared to low risk have 6.3 times the risk of nodal metastasis (95% CI, 1.67–23.8; P = 0.007).

Conclusion

Low-risk endometrioid uterine cancer criteria may be used to help guide treatment planning for reoperation in patients with incomplete surgical staging information.

INTRODUCTION

Carcinoma of the uterus is the most common gynecologic cancer diagnosed in the United States with greater than 40,000 women affected annually.1 Despite this high prevalence, management is an issue of significant debate and controversy. Balancing complete staging information for both prognostic and potential therapeutic benefits against potential perioperative morbidity and mortality has fostered numerous studies to estimate the relationship between clinical and pathologic characteristics in endometrial cancer.

It has been almost 25 years since the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) first published their seminal manuscript on surgical pathologic spread patterns in 621 patients with endometrial cancer.2 Key findings of this study include the importance of grade and depth of invasion, which enabled the authors to stratify patients into three risk categories for nodal metastases.

In 2000, Mariani et al from the Mayo clinic published their study that demonstrated a subset of endometrial cancer with favorable characteristics which included three low-risk features involving tumor size ≤ 2cm, grade 1 or 2 tumors, and depth of invasion ≤ 50%. In their study they demonstrated a 5% risk for nodal metastasis and 97% cancer-specific survival in this low-risk group.4 A subsequent recent prospective study from the Mayo clinic correlated tumor size, grade, and depth of invasion with lymph node metastasis in 422 consecutive patients undergoing routine formal surgical staging.5 The “Mayo Criteria” has led to several studies looking at the potential applicability of the low-risk criteria at other medical centers. Most recently a retrospective multicenter review demonstrated the potential applicability of frozen and final pathology to predict low risk endometrial cancer with a 98.2% negative predictive value.6 Although the rate of unexpected diagnoses of endometrial cancer is not clear, a recent study utilizing the Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) program demonstrated that approximately 62% (24,436/39,396) of women underwent a hysterectomy without an associated lymphadenectomy.9

Currently there are no clear management strategies for those unstaged patients identified with endometrial cancer in the postoperative setting; the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines defer to individual practice patterns.7

Recent evidence suggests that staging of patients with endometrial cancer may have a prognostic role, while a therapeutic role at this time is less clear.10–12 Risk/Benefit profiles of surgical intervention often guide staging, but clear information to patients and clinicians is not readily available.13 In light of these concerns, we conducted a review of LAP2, a large prospective trial in endometrial cancer staging conducted in the USA, using a Modified Mayo Criteria (MMC) to assess the risk of nodal disease in women with endometrial cancer.13

METHODS

This is a post hoc analysis from the previously identified 2,516 women enrolled in the IRB-approved GOG study (GOG 2222 or LAP2).13 All patients signed a locally approved informed consent and authorization permitting release of personal health information. The current study was approved by the University of Louisville Medical Center Institutional Review Board. Inclusion criteria for the patients in this analysis were those women with uterine cancer of endometrioid histology, and complete clinicopathologic data involving the modified risk criteria. According to the modified Mayo Criteria, we identified each patient as low risk or high risk for extra uterine disease requiring systematic lymphadenectomy. Patients identified as low risk (LR) for nodal metastasis were modified from the Mayo Criteria endometrial cancer characteristics with three specific criteria on final pathology reports:

less than 50% invasion;

tumor size less than 2 cm; and

well or moderately differentiated (grade 1 or grade 2) endometrioid histology.

Myometrial invasion and primary tumor data were abstracted by chart review, and histologic classification by central review by the GOG Pathology Committee. Unlike the previously reported Mayo Criteria, frozen section analysis was not available to us for review.5

Differences between patient characteristics for the low- and high-risk (HR) groups were examined using the Pearson χ2 test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables and the Wilcoxon–Mann–Whitney test for continuous variables, with statistical significance defined as P < 0.05. A logistic model was used to estimate a patient’s risk of nodal metastasis based on risk-group membership. The model adjusted for relevant prognostic factors and baseline characteristics that differed significantly between the risk groups (tumor grade, depth of invasion, age); tumor extent, and surgical stage were considered, but dropped when shown to contribute little to the variation in the model. Multicollinearity among the model covariates was examined through the method of Generalized Variance Inflation Factors (GVIF) described by Fox and Monette, and found negligible.14 The Hosmer–Lemeshow–Cressie goodness-of-fit test failed to find a significant lack of fit (P = 0.47) in the model. By the “rare-disease assumption,” i.e. if the proportion of nodal metastases in the low-risk group is < 0.10 (= 0.008), the odds ratio (OR) approximates the relative risk (RR) of nodal metastasis. All statistical analyses were performed using the R programming language and environment.15

RESULTS

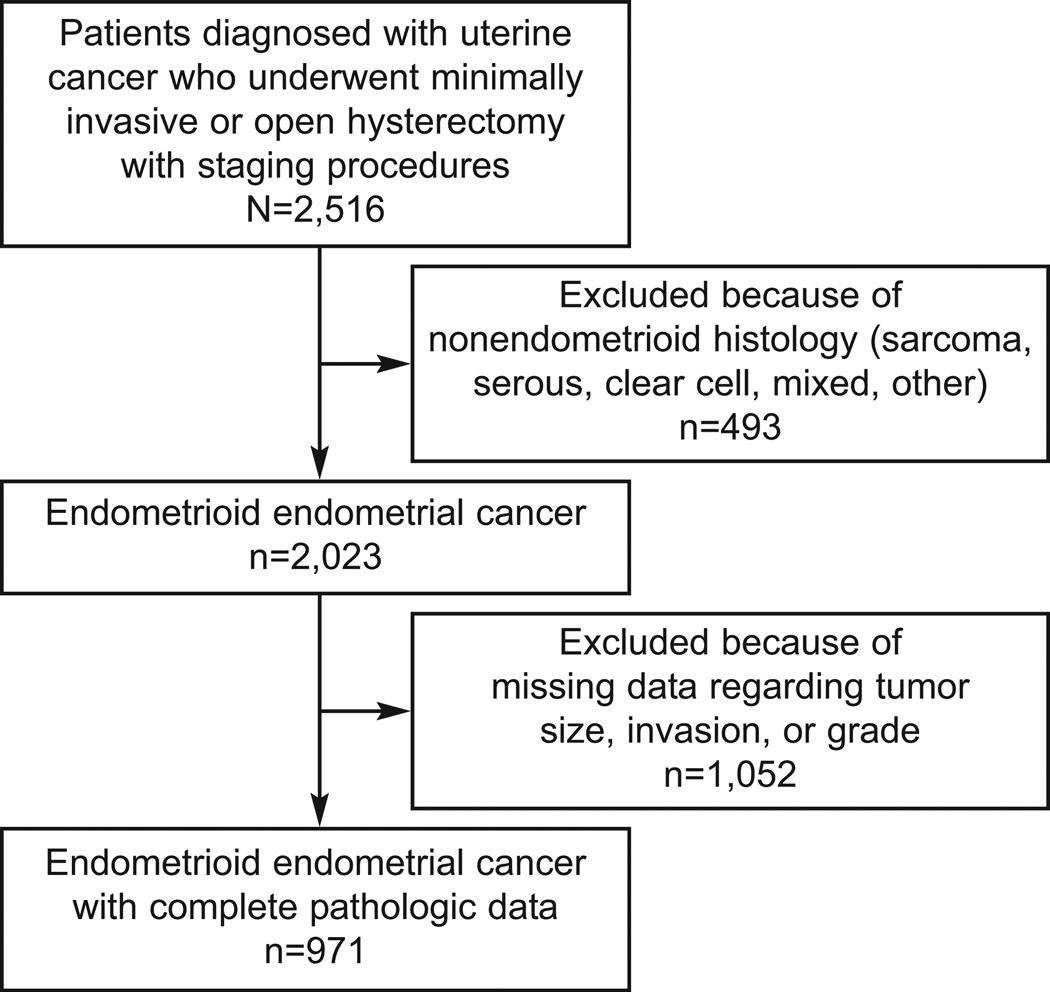

Only patients enrolled in LAP2 were included in this study. Among the 2516 eligible patients from the original LAP2 study 13, we included only those that had complete information criteria of grade, myometrial invasion (MI), and primary tumor diameter (PTD), and whose tumors were classified by prospective pathology review as endometrioid adenocarcinomas; those restrictions left a patient population of 971 (39%), as shown in the CONSORT diagram in Figure 1. A total of 2023 patients with endometrioid uterine cancer were reviewed. All patients had documented tumor grade. There were 51.3% (1038/2023) of patients missing data regarding tumor size; 51.4% (1041/2023) of patients were missing data regarding depth of invasion; and 52% (1052/2023) of patients were missing data on one or both of size and invasion leading to the 971 patients included in this study. The majority of patients were Caucasian, and the median age was 60 years.

Figure 1.

Flow of patients through study

Patients with nodal metastasis did not demonstrate any significant clinical differences from those patients without nodal metastasis in regards to age, race/ethnicity, or performance status (Table 1). As expected, patients with nodal metastases were more likely to have higher grade tumors, increased depth of invasion, and larger tumor size (Table 1). Individual LR uterine pathologic characteristics were associated with an up to 4.8% risk for lymph node metastasis (Table 1). According to the MMC, we identified each patient as LR or HR for dissemination (metastatic disease in the lymph nodes) requiring systematic lymphadenectomy. The patient characteristics for the LR and HR groups are shown in Table 2, with patients in the high-risk group significantly older (HR median age of 61 8 vs. LR median age of 59.6; P = 0.008) than low-risk patients. As this was a post hoc analysis patients with missing data were excluded – however, we found no statistically significant difference between the patients missing data by presence of nodal metastasis (Table 3).

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics by Presence of Nodal Metastasis

| No n = 906 |

Yes n = 65 |

Test Statistic (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age years | 60.5 (54.3, 69.1) | 62.7 (53.0, 69.6) | 0.869* |

| Weight kg | 74 (64, 89) | 70 (61, 83) | 0.104* |

| Height cm | 162 (157, 166) | 162 (156, 165) | 0.446* |

| BMI kg/m2 | 28.7 (24.6, 34.3) | 27.6 (24.7, 32.0) | 0.213* |

| Race or ethnicity | 0.239† | ||

| White | 88.4 (801) | 89.2 (58) | |

| Hispanic | 3.8 (34) | 0.0 (0) | |

| Black | 4.0 (36) | 3.1 (2) | |

| Asian | 2.9 (26) | 4.6 (3) | |

| Other | 1.0 (9) | 3.1 (2) | |

| Performance status | 0.346‡ | ||

| Normal, asymptomatic | 89.6 (812) | 87.7 (57) | |

| Symptomatic, ambulatory | 9.9 (90) | 10.8 (7) | |

| Symptomatic, abed less than 50% | 0.4 (4) | 1.5 (1) | |

| Surgical technique | |||

| Open surgery | 92 (319) | 8 (29) | 0.13† |

| Laparoscopy | 94 (587) | 6 (36) | |

| Uterine characteristics§ | |||

| Tumor grade 2 or less (n=816) | 95.2 (777) | 4.8 (39) | < 0.001† |

| Depth of invasion less than 50% (n=789) | 96.1 (758) | 3.9 (31) | < 0.001† |

| Tumor size less than 2 cm (n=466) | 96.8 (451) | 3.2 (15) | < 0.001† |

BMI, body mass index.

Data are median (lower quartile, upper quartile) for continuous variables or percent (frequency) unless otherwise specified.

Wilcoxon test

Pearson test

Fisher’s exact test

Percentages based on grade, depth of invasion, and tumor size.

Table 2.

Patient Characteristics by Risk-Group Membership

| Low n = 389 |

High n = 582 |

Test Statistic (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, years | 59.6 (53.7, 6.7) | 61.8 (54.8, 70.0) | 0.008* |

| Weight, kg | 73 (63, 87) | 64 (75, 89) | 0.233* |

| Height, cm | 162.0 (157.0, 166.0) | 162.0 (157.0, 166.8) | 0.733* |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.9 (24.2, 34.3) | 28.9 (24.7, 34.2) | 0.239* |

| Race or ethnicity | 0.183† | ||

| White | 90.2 (351) | 87.3 (508) | |

| Hispanic | 2.1 (8) | 4.5 (26) | |

| Black | 3.1 (12) | 4.5 (26) | |

| Asian | 3.1 (12) | 2.9 (17) | |

| Other | 1.5 (6) | 0.9 (5) | |

| Performance status | 0.247‡ | ||

| Normal, asymptomatic | 90.0 (350) | 89.2 (519) | |

| Symptomatic, ambulatory | 10.0 (39) | 10.0 (58) | |

| Symptomatic, bed less than 50% | 0.0 (0) | 0.9 (5) | |

| Surgical technique | |||

| Open surgery | 37 (129) | 63 (219) | 0.16† |

| Laparoscopy | 42 (260) | 58 (363) | |

| Locally advanced stage | |||

| Stage IIB | 2.1 (8) | 4.1 (24) | 0.077† |

| Stage IIIA§ | 2.3 (9) | 6.5 (38) | 0.003† |

BMI, body mass index.

Data are median (lower quartile, upper quartile) for continuous variables or percent (frequency) unless otherwise specified.

Wilcoxon test

Pearson test

Fisher’s exact test

Stage IIIa patients with adnexal involvement were more likely to have high-risk criteria (86.7% or 13/15 in the high-risk group compared with 13.3% or 2/15 in the low-risk group).

Table 3.

Missing Data by Presence of Nodal Metastasis

| no n = 1881 |

yes n = 142 |

Test Statistic (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Missing risk-group data? | 0.58 | ||

| No | 48.2 (906) | 45.8 (65) | |

| Yes | 51.8 (975) | 54.2 (77) |

Data are percent (frequency) unless otherwise specified. Pearson test was used.

Presence of Nodal Metastasis by Risk Group

Approximately 40% (or 389/971) of patients in this study were found to be low risk based on the modified mayo criteria (MMC) with a rate of nodal metastasis of only 0.8% (3/389; exact 95% CI, 0.16%–2.2%). We analyzed the risk of a patient’s having nodal metastasis by determining the odds of metastasis for patients in the low- and the HR group (Table 4) using logistic regression. The regression controlled for the following potential confounders: tumor grade, depth of myometrial invasion, and patient age, all of which were significantly different between the groups. The odds of nodal metastasis were greater for patients in the HR group ([OR] = 6.3; 95% CI, [1.67–23]; P = 0.007). All 3 patients in the LR group that had nodal metastasis were Caucasian, and had moderately differentiated endometrial histology. We also identified the correlative effects of positive pelvic lymph node involvement with peri-aortic lymph node involvement (Table 5). Patients with HR MMC but negative pelvic lymph nodes had a statistically decreased risk for peri-aortic lymph node metastasis (12/520 or 2.3% vs. 19/50 or 38%; P < 0.001).

Table 4.

Risk-Group Characteristics by Risk-Group Membership

| Low n = 389 |

High n = 582 |

Test Statistic (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tumor grade (differentiation) | < 0.001 | ||

| Good | 41.4 (161) | 18.4% (107) | |

| Moderate | 58.6 (228) | 55.0 (320) | |

| Poor | 0.0 (0) | 26.6 (155) | |

| Myometrial invasion | < 0.001 | ||

| None | 43.4 (169) | 4.0 (23) | |

| Endometrial | 25.7 (100) | 21.6 (126) | |

| Less than 50% myometrial | 30.8 (120) | 43.1 (251) | |

| 50% or more myometrial | 0.0 (0) | 29.7 (173) | |

| Serosal | 0.0 (0) | 1.5 (9) | |

| Tumor size | < 0.001 | ||

| None | 48.8 (190) | 4.0 (23) | |

| Less than 2 cm | 51.2 (199) | 9.3 (54) | |

| 2 cm or more | 0.0 (0) | 86.8 (505) | |

| Nodal metastasis present? | < 0.001 | ||

| No | 99.2 (386) | 89.3 (520) | |

| Yes | 0.8 (3) | 10.7 (62) |

Data are percent (frequency) unless otherwise specified. Pearson test was used.

Table 5.

Pelvic and Periaortic Nodal Metastasis Risk in High-Risk Patients

| Periaortic lymph nodes positive (n=582) | No n = 551 |

Yes n = 31 |

Test Statistic (P) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pelvic lymph nodes positive (n=582) | <0.001 | ||

| No (n=532) | 98.7 (520) | 2.3 (12) | |

| Yes (n=50) | 62 (31) | 38 (19) |

Data are percent (frequency) unless otherwise specified. Pearson test was used.

Complication Rates

Complications and Adverse Events by Risk-Group Membership (Table 6) suggests a statistically higher perioperative complication rate in the HR MMC group, but the p-values have not been adjusted for multiple testing and should be interpreted with caution. It is important to note, however, the perioperative complication risk (defined as readmission, reoperation, and death) in the LR MMC group was higher than the identified nodal metastasis risk (6.4% or 25/389 vs. 0.8% or 3/389; P < 0.001).

Table 6.

Complications and Adverse Events by Risk-Group Membership

| Low n = 389 |

High n = 582 |

Test Statistic (P) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intraoperative complications | |||

| Any | 7.5 (29) | 10.1 (59) | 0.154 |

| Bowel | 1.0 (4) | 2.7 (16) | 0.064 |

| Veins | 2.3 (9) | 3.1 (18) | 0.469 |

| Artery | 1.3 (5) | 1.4 (8) | 0.906 |

| Gastrointestinal tract | 0.0 (0) | 0.7 (4) | 0.101 |

| Bladder | 0.8 (3) | 1.5 (9) | 0.284 |

| Ureter | 0.8 (3) | 0.9 (5) | 0.882 |

| Other | 1.3 (5) | 1.7 (10) | 0.592 |

| Postoperative adverse events (grade 2 or higher) | |||

| Any | 11.1 (43) | 16.0 (93) | 0.030 |

| Urinary tract infection | 2.3 (9) | 2.2 (13) | 0.935 |

| Fever | 2.6 (10) | 3.1 (18) | 0.634 |

| Pelvic cellulitis | 1.0 (4) | 1.4 (8) | 0.632 |

| Abscess | 1.0 (4) | 1.2 (7) | 0.801 |

| Venous thrombophlebitis | 0.8 (3) | 0.9 (5) | 0.882 |

| Pulmonary embolus | 0.5 (2) | 1.0 (6) | 0.383 |

| Bowel obstruction | 0.8 (3) | 0.5 (3) | 0.618 |

| Ileus | 3.1 (12) | 3.6 (21) | 0.659 |

| Pneumonia | 0.5 (2) | 1.2 (7) | 0.273 |

| Wound infection | 2.1 (8) | 2.9 (17) | 0.405 |

| Urinary fistula | 0.5 (2) | 0.2 (1) | 0.346 |

| Bowel fistula | 0.0 (0) | 0.9 (5) | 0.067 |

| Congestive heart failure | 0.3 (1) | 0.3 (2) | 0.812 |

| Arrhythmia | 1.0 (4) | 1.0 (6) | 0.997 |

| Perioperative and postoperative period | |||

| Blood transfusion | 1.3 (5) | 3.1 (18) | 0.070 |

| Antibiotics | 14.1 (55) | 17.2 (100) | 0.205 |

| Readmission | 4.9 (19) | 5.0 (29) | 0.945 |

| Reoperation | 1.0 (4) | 1.9 (11) | 0.286 |

| Treatment-related deaths | 0.5 (2) | 0.2 (1) | 0.346 |

| Hospital stay more than 2 days | 55.5 (216) | 63.7 (371) | 0.010 |

Data are percent (frequency) unless otherwise specified.

DISCUSSION

LR criteria in endometrioid endometrial cancer hysterectomy specimens have been associated with a decreased risk for nodal metastasis. Approximately 40% (or 389/971) of patients in this study were found to be low risk based on the modified Mayo criteria (MMC) with a rate of nodal metastasis of only 0.8% (3/389; exact 95% CI, 0.16%–2.2%).

Our study demonstrates that LR criteria correspond to a low rate of nodal disease, and are associated with a decreased risk of lymph node metastasis in patients with endometrioid endometrial cancer. Our study supports the previously published associations between risk criteria involving tumor size, grade, and myometrial invasion with nodal metastasis risk. 3, 5, 16 However, those previous studies were single institution reviews with limited ability to translate to general clinical practice. 3, 5, 16 Heterogeneity of tumor specimens included non-endometrioid tumors, and, therefore, added to potential risk of extra uterine disease.3, 5, 16

Recent studies have demonstrated the limitation of preoperative testing to identify patients at risk for nodal metastasis in early stage endometrial cancer which often leaves staging to individual surgeon preference.17 Management of clearly identified endometrial cancer is even now heterogeneous with a wide range of management strategies.18 Clinical and pathologic factors that predict reduced risk lymph node involvement could help guide more conservative therapy including simple hysterectomies, while those that predict increased risk for lymph node involvement may justify aggressive surgical management to help with identification of nodal metastasis. Patients with a postoperative hysterectomy diagnosis of endometrial cancer could be triaged into categories of patients who may benefit from surgical staging with a clearer discussion of risks and benefits prior to surgical intervention.

These findings should be validated in a prospective multicenter trial that includes the predictive value of LR in the frozen section and final pathology in the setting of diagnosed endometrial cancer. Our hypothesis would be that criteria, such as the MMC, could be utilized and reproducible in both frozen and final pathology in a multicenter community setting.

This study is limited by its retrospective nature and missing data, but the findings are still suggestive of an association and need to evaluate the uterine specimen to help guide therapy. Another potential limitation of this study is that although histology and grade were centrally reviewed, tumor size and depth of invasion in general were not unless re-review was warranted (e.g. a staging discrepancy) and the missing data may limit the conclusions. Future research will also be needed to elucidate the impact on the MMC in those patients who undergo dilation and curettage vs. those patients who undergo an endometrial biopsy to diagnose endometrial cancer. The key component of this study regarding tumor size should be explored and multicenter research emphasizing it’s importance will be needed so clinicians and pathologists will begin to incorporate size as a factor along with grade and depth of invasion. Other important criteria to consider regarding lymph node dissection includes nodal count to ensure decreased risk of nodal metastases. Nodal count is often limited by retrospective single institution reviews and pathology technique.19–21 Adequate nodal counts to identify a positive lymph node has also been reported from the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) database from the National Cancer Institute (NCI) to have a range of 21–25 lymph nodes.22 In our manuscript we did have a statistically significant difference in median nodal count between open or laparoscopic technique (22.5 vs 21.0; P = 0.017), Low or High risk MMC (20.0 vs. 22.0; P = 0.023), and identified nodal metastases (−nodes of 21.0 vs. +nodes 25, P = 0.018), however the median count for these patients fell within and or above previously published adequate nodal count criteria.

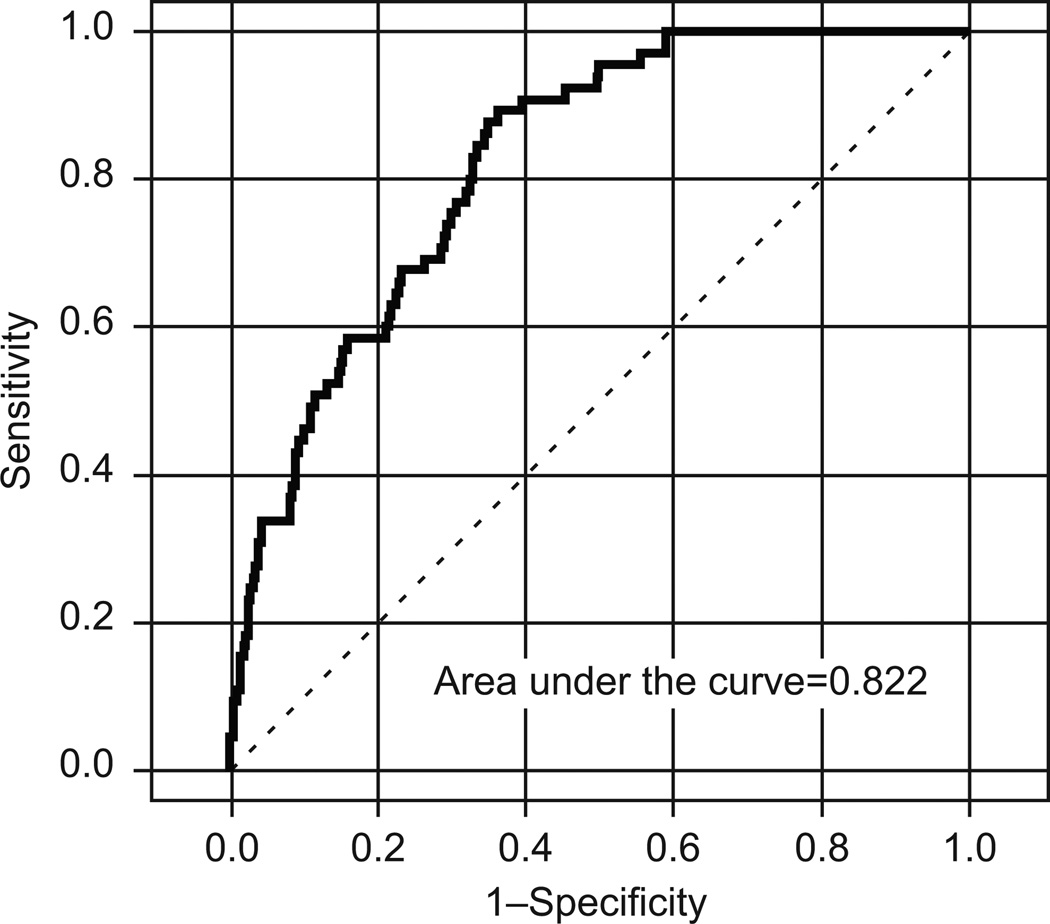

The ROC curve for our logistic model (Figure 2) shows a promising AUC of 0.822 (95% bootstrap CI, 0.77–0.86), but the low prevalence of confirmed nodal metastasis among the study population (6.27%; 95% CI, 0.05–0.08) suggests that the risk-group test's sensitivity and specificity, which depend only on the test itself, are inadequate for characterizing the study population. A simpler model that discriminates for nodal metastasis only by HR or LR group membership has a positive predictive value (PPV) of 0.11 (95% CI, 0.083–0.134), but a negative predictive value (NPV) of 0.992 (95% CI, 0.978–0.998). Therefore, neither model is particularly useful for identifying patients at risk for nodal metastasis; but the simpler model seems potentially useful for identifying patients without nodal metastasis. It is important to note that no single risk-group criterion (grade, depth of invasion, or size) was, by itself or paired with another criterion, capable of generating an adequately large PPV or NPV in the study population. For example, tumor grade of 1 or 2 was found in 60% of the patients with identified nodal metastases (Table 1). This alone would limit the utility of endometrial sampling prior to surgery to help predict lymph node metastases. Frozen section data were not reported in this multicenter review. Previous reports have suggested limitations of frozen section in endometrial cancer; however, the use of binary (MMC LR vs. HR) criteria was not used, and a streamlined management may lead to more consistent intraoperative consultation.17

Figure 2.

Receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve of logistic model.

Minimally invasive surgical technique including robotic surgery may be associated with decreased perioperative complication rates, and the morbidity reported in this study may be higher than currently being seen in practice. However, given the median BMI of 28.6 in this study and 89.5% asymptomatic performance status (Table 1) seen in this study surgical improvements in technique may be offset by current patient co-morbid conditions, which are often worse outside of a clinical trial.

In this multicenter post hoc analysis, MMC low-risk endometrioid uterine cancer characteristics were associated with a 0.8% rate of nodal metastasis. This data adds further support to the utilization of tumor size as a criterion for lymph node dissection promoted by the Mayo Clinic. These criteria should be used to help guide treatment planning for reoperation in patients with incomplete surgical staging information.

Acknowledgments

Supported by National Cancer Institute grants to the Gynecologic Oncology Group Administrative Office (CA27469) and the Gynecologic Oncology Group Statistical and Data Center (CA37517), and also supported by the Gynecologic Oncology Young investigator award (Mentor Robert L. Coleman, MD).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Presented in part at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology Annual Meeting on Women's Cancer, Orlando, FL, March 6–9, 2011.

For a list of participating institutions belonging to the Gynecologic Oncology Group, see the Appendix online at http://links.lww.com/xxx.

Financial Disclosure: The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Xu J, Ward E. Cancer statistics, 2010. CA Cancer J Clin. 2010;60:277–300. doi: 10.3322/caac.20073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Creasman WT, Morrow CP, Bundy BN, Homesley HD, Graham JE, Heller PB. Surgical pathologic spread patterns of endometrial cancer. A Gynecologic Oncology Group Study. Cancer. 1987;60:2035–2041. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19901015)60:8+<2035::aid-cncr2820601515>3.0.co;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schink JC, Lurain JR, Wallemark CB, Chmiel JS. Tumor size in endometrial cancer: a prognostic factor for lymph node metastasis. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;70:216–219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mariani A, Webb MJ, Keeney GL, et al. Low-risk corpus cancer: is lymphadenectomy or radiotherapy necessary? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1506–1519. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.107335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mariani A, Dowdy SC, Cliby WA, et al. Prospective assessment of lymphatic dissemination in endometrial cancer: a paradigm shift in surgical staging. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;109:11–18. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.01.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Convery PA, Cantrell LA, DiSanto N, et al. Retrospective review of an intraoperative algorithm to predict lymph node metastasis in low-grade endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2011;123:65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2011.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.ACOG practice bulletin, clinical management guidelines for obstetrician-gynecologists, number 65, August 2005: management of endometrial cancer. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:413–425. doi: 10.1097/00006250-200508000-00050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trimble CL, Kauderer J, Zaino R, Silverberg S, Lim PC, Burke JJ, 2nd, et al. Concurrent endometrial carcinoma in women with a biopsy diagnosis of atypical endometrial hyperplasia: a Gynecologic Oncology Group study. Cancer. 2006;106:812–819. doi: 10.1002/cncr.21650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chan JK, Wu H, Cheung MK, Shin JY, Osann K, Kapp DS. The outcomes of 27,063 women with unstaged endometrioid uterine cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:282–288. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chan JK, Cheung MK, Huh WK, Osann K, Husain A, Teng NN, et al. Therapeutic role of lymph node resection in endometrioid corpus cancer: a study of 12,333 patients. Cancer. 2006;107:1823–1830. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kitchener H, Swart AM, Qian Q, Amos C, Parmar MK. Efficacy of systematic pelvic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (MRC ASTEC trial): a randomised study. Lancet. 2009;373:125–136. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61766-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Todo Y, Kato H, Kaneuchi M, Watari H, Takeda M, Sakuragi N. Survival effect of para-aortic lymphadenectomy in endometrial cancer (SEPAL study): a retrospective cohort analysis. Lancet. 2010;375:1165–1172. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)62002-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Walker JL, Piedmonte MR, Spirtos NM, Eisenkop SM, Schlaerth JB, Mannel RS, et al. Laparoscopy compared with laparotomy for comprehensive surgical staging of uterine cancer: Gynecologic Oncology Group Study LAP2. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:5331–5336. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.22.3248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fox J, Monette G. General collinearity diagnostics. JASA. 1992;87:178–183. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Team RDC. Computing RFfS. Vienna, Austria: R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. ed. (vol 2009) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KB, Ki KD, Lee JM, Lee JK, Kim JW, Cho CH, et al. The risk of lymph node metastasis based on myometrial invasion and tumor grade in endometrioid uterine cancers: a multicenter, retrospective Korean study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2009;16:2882–2887. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0535-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leitano MM, Jr, Kehoe S, Barakat RR, Alektiar K, Gattoc LP, Rabitt C, et al. Accuracy of preoperative endometrial sampling diagnosis of FIGO grade 1 endometrial adenocarcinoma. Gynecol Oncol. 2008;111:244–248. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2008.07.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Soliman PT, Frumovitz M, Spannuth W, Greer MJ, Sharma S, Schmeler KM, et al. Lymphadenectomy during endometrial cancer staging: practice patterns among gynecologic oncologists. Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:291–294. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang M, Chadha M, Musa F, et al. Lymph nodes: is total number or station number a better predictor of lymph node metastasis in endometrial cancer? Gynecol Oncol. 2010;119:295–298. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lutman CV, Havrilesky LJ, Cragun JM, et al. Pelvic lymph node count is an important prognostic variable for FIGO stage I and II endometrial carcinoma with high-risk histology. Gynecol Oncol. 2006 doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.11.032. Ellis Fischel Cancer Center: 92–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milam MR, Abaid L, dos Reis R, et al. Microscopic evaluation of lymph-node-bearing tissue in early-stage cervical cancer: a dual-institution review. Ann Surg Oncol. 2010;17:1106–1110. doi: 10.1245/s10434-009-0870-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chan JK, Urgan R, Cheung MK, et al. Lymphadenectomy in endometrioid uterine cancer staging: how many lymph nodes are enough? A study of 11,443 patients. Cancer. 2007;109:2454–2460. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]