Summary

Autophagy is a cellular degradation process that can capture and eliminate intracellular microbes by delivering them to lysosomes for destruction. However, pathogens have evolved mechanisms to subvert this process. The intracellular bacteria Brucella abortus ensures its survival by forming the Brucella-containing vacuole (BCV) that traffics from the endocytic compartment to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where the bacterium proliferates. We show that Brucella replication in the ER is followed by BCV conversion into a compartment with autophagic features (aBCV). While Brucella trafficking to the ER was unaffected in autophagy-deficient cells, aBCV formation required the autophagy initiation proteins ULK1, Beclin 1 and ATG14L, and PI3-kinase activity. However, aBCV formation was independent of the autophagy elongation proteins ATG5, ATG16L1, ATG4B, ATG7 and LC3B. Furthermore, aBCVs were required to complete the intracellular Brucella lifecycle and for cell-to-cell spreading, demonstrating that Brucella selectively co-opts autophagy initiation complexes to subvert host clearance and promote infection.

Introduction

Pathogenic microbes with an intracellular lifestyle have evolved various survival strategies to avoid microbicidal mechanisms and generate unique intracellular niches for replication and persistence, by modulating cellular processes. Intracellular parasites or bacteria typically reside either within a membrane-bound vacuole, which they modify through controlled maturation of their original phagosome, or freely in the cytosol following phagosomal escape. Regardless of their intracellular location, invading microorganisms can be recognized as foreign and engaged by macroautophagy (herein referred to as autophagy), an intracellular process of capture and lysosomal degradation of damaged organelles, protein aggregates and cytosolic content with a prominent role in intracellular innate immunity (Levine et al., 2011). Selective antibacterial autophagy, also called xenophagy, can either target cytosolic bacteria (Checroun et al., 2006; Collins et al., 2009; Nakagawa et al., 2004; Ogawa et al., 2005; Rich et al., 2003) or bacteria in both intact and damaged vacuolar compartments (Birmingham et al., 2006; Gutierrez et al., 2004) and deliver them to lysosomes, thereby controlling their intracellular survival and replication.

Autophagy is initiated by the nucleation of an isolation membrane that elongates to envelop autophagic targets into a double membrane vacuole, the autophagosome, which in turn progressively matures and eventually fuses with lysosomes to create a degradative autolysosome (Levine et al., 2011). The membrane dynamics of the autophagic process involve various protein complexes required for nucleation and elongation of the autophagosome. Key to the initiation of autophagy is the ULK1 complex, which translocates to subdomains of the endoplasmic reticulum (ER), where it recruits a Class III phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase (PI3-kinase) complex comprised of the autophagy proteins VPS34, VPS15, Beclin 1 and Atg14L (Itakura and Mizushima; Matsunaga et al., 2010; Matsunaga et al., 2009), which in turn generates phosphatidylinositol-3-phosphate (PI3P) on omegasomes (Axe et al., 2008) that serve as cradles for the biogenesis of isolation membranes. Elongation of the isolation membrane into an autophagosome involves two ubiquitin-like conjugation pathways, both dependent on the autophagy protein ATG7, which in aggregate generate the ATG12-ATG5/ATG16L1 protein complex and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE)-conjugated ATG8 homolog LC3 (He and Klionsky, 2009). Given the essential roles of these autophagy protein complexes, depletion of these proteins typically abrogates or severely impairs autophagy, xenophagic control of intracellular microorganisms (Birmingham et al., 2006; Levine et al., 2011; Zheng et al., 2009) and resistance to infection (Zhao et al., 2008), although some ATG5 and ATG7-independent macroautophagic and xenophagic processes have been reported (Collins et al., 2009; Nishida et al., 2009). Due to its prominent antimicrobial functions, various intracellular pathogens have evolved to protect themselves against xenophagic capture, including the cytosolic bacteria Listeria monocytogenes (Birmingham et al., 2007; Yoshikawa et al., 2009) and Shigella flexneri (Ogawa et al., 2005). Additionally, general autophagy has been invoked in the intracellular trafficking of the vacuolar bacteria Coxiella burnetii (Gutierrez et al., 2005), Yersinia pestis and pseudotuberculosis (Moreau et al., 2010; Pujol et al., 2009), Porphyromonas gingivalis (Dorn et al., 2001) and Brucella abortus (Pizarro-Cerda et al., 1998a).

Bacteria of the genus Brucella are the causative agent of brucellosis, a worldwide zoonosis with significant health and economic consequences (Pappas et al., 2005). Essential to the virulence of these bacteria is their ability to enter, survive, proliferate and persist within a variety of host cell types including professional phagocytes such as macrophages and dendritic cells (Archambaud et al., 2010; Salcedo et al., 2008). Brucella has evolved to manipulate intracellular membrane trafficking processes to foster its survival and growth. Following phagocytic uptake or internalization, Brucella resides within a membrane-bound compartment, the Brucella-containing vacuole (BCV), which traffics along the endocytic pathway during the first 8 h post infection (pi) and undergoes limited fusion with the lysosomal compartment (Starr et al., 2008). These interactions with late endocytic/lysosomal compartments are necessary for induction of the VirB Type IV secretion apparatus (Boschiroli et al., 2002; Starr et al., 2008), a major virulence factor that translocates effector molecules into the host cell (de Jong et al., 2008; Marchesini et al., 2011) and likely promotes endosomal BCV (herein referred to as eBCV) trafficking towards the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) (Celli et al., 2003; Comerci et al., 2001). BCV trafficking to the ER occurs via interactions with the transitional ER between 4 and 12 h pi, which requires the small GTPases Sar1 (Celli et al., 2005) and Rab2 (Fugier et al., 2009) and culminates in endosomal to ER membrane exchange on the BCV (Celli et al., 2003). ER-derived BCVs are replication-permissive organelles (herein referred to as rBCVs) that are generated by 12 h pi (Celli et al., 2003; Comerci et al., 2001; Pizarro-Cerda et al., 1998a; Salcedo et al., 2008). Brucella replication also requires the ER transmembrane protein IRE1α (Qin et al., 2008), a sensor of the unfolded protein response (UPR) upon ER stress that also contributes to autophagy induction (Ogata et al., 2006).

While the Brucella intracellular cycle is well defined from entry to replication in the ER, with initial rounds of replication achieved within 12 to 24 h post infection (pi) (Arellano-Reynoso et al., 2005; Bellaire et al., 2005; Celli et al., 2003; Celli et al., 2005; Comerci et al., 2001; Fugier et al., 2009; Pizarro-Cerda et al., 1998b; Salcedo et al., 2008), steps subsequent to bacterial replication in rBCVs are unknown. Here we have examined late stages of the Brucella intracellular cycle in both macrophages and epitheloid cells. We report a post-ER replication compartment that is initiated at the ER and converts rBCVs into vacuoles with autophagic features in a Beclin1-, ULK-1- and ATG14L-dependent, but ATG5-, ATG16L1-, ATG4B-, ATG7- and LC3B-independent manner. Importantly, rBCV conversion into these vacuoles completes the intracellular cycle of Brucella and promotes cell-to-cell spread. These findings demonstrate a selective subversion of autophagy nucleation complexes by a pathogenic bacterium in favor of an infection process.

Results

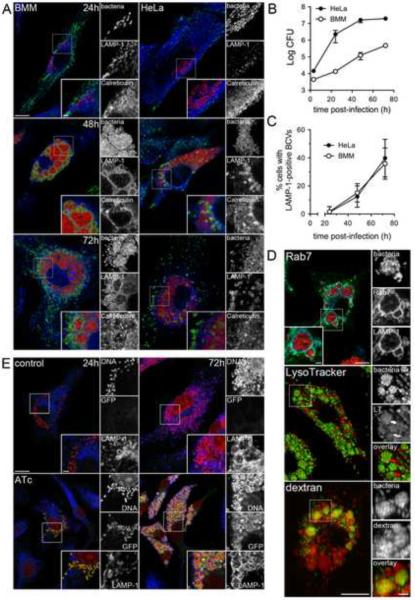

Brucella translocates into endosomal vacuoles at late stages of its intracellular cycle

To examine late stages of the Brucella intracellular cycle, we first monitored intracellular growth of the virulent wild type B. abortus strain 2308 in either C57BL/6J murine bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) or in the human epithelioid cell line HeLa. Increasing numbers of viable intracellular bacteria were recovered during a 72 h infection period, demonstrating bacterial replication in both cell types (Fig. 1B). Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy analysis revealed Brucella already recognized replication patterns within LAMP-1-negative, Calreticulin-positive rBCVs at 24 h pi (Fig. 1A), indicating that internalized bacteria had generated ER-derived replicative organelles (rBCVs) at this stage. At 48 h pi, most infected cells bore increasing numbers of ER-localized, replicating bacteria. However, 15 ± 6.5% of infected BMMs contained clusters of bacteria enclosed within large LAMP-1-positive vacuoles, and 12 ± 7.6% of infected HeLa cells harbored LAMP-1-positive vacuoles containing either one or more bacteria embedded within, or at the periphery, of rBCV clusters (Fig. 1A and C). This compartment was more prevalent by 72 h pi, where 36 ± 11% and 40 ± 13% of infected BMMs and HeLa cells contained LAMP-1-positive, calreticulin-negative vacuoles (Fig. 1A and C), suggesting that replicating Brucella translocate to a vacuolar compartment that is phenotypically distinct from ER-derived rBCVs.

Figure 1.

Post-ER replication translocation of Brucella into an endosomal compartment. (A) Representative confocal micrographs of BMMs (left-hand panels) and HeLa cells (right-hand panels) infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus 2308 (red) and immunostained for LAMP-1 (green) and calreticulin (blue) at 24, 48 and 72 h pi. Scale bars are 10 and 2 μm. (B) Intracellular growth of B. abortus strain 2308 in either BMMs (open circles) or HeLa cells (closed circles). Cells were infected and intracellular CFUs enumerated at 3, 24, 48 and 72 h pi. Data are means ± SEM from a representative experiment performed in triplicate. (C) Quantification of late LAMP-1-positive BCV formation at 24, 48 and 72 h pi in BMMs (open circles) and HeLa cells (closed circles). Data are expressed as percentage of infected cells containing late LAMP-1-positive BCV and are means ± SD from three independent experiments. (D) Representative confocal micrographs of BMMs infected with either DsRedm-expressing (Rab7 panel) or GFP-expressing (LysoTracker and dextran panels) B. abortus 2308 and processed for labeling of Rab7 and LAMP-1 (Rab7), acidic compartments (LysoTracker) or endocytic compartments (dextran). Scale bars are 10 and 2 μm (E) Representative confocal micrographs of BMMs infected with B. abortus 2308 expressing an anhydrotetracycline (ATc)-inducible GFP that were left untreated or treated for 6 h with 200 nM ATc prior to processing at 24 and 72 h pi for bacterial and host cell DNA (red) and LAMP-1 (blue) labeling. Scale bars 10 and 2 μm. See also Figure S1.

Consistently, these late BCVs recruited the late endosomal/lysosomal GTPase Rab7, were acidified and accumulated fluid phase markers in BMMs (Fig. 1D), demonstrating their fusogenocity with late endocytic compartments. To verify that these large endosomal vacuoles harbored live bacteria, BMMs were infected with B. abortus 2308 expressing GFP under an anhydrotetracycline (ATc)-inducible promoter and examined for bacterial fluorescence upon induction. Like bacteria within either eBCVs (8h pi; data not shown) or rBCVs (24h pi, Fig. 1E), those contained within LAMP-1-positive vacuoles at 72 h pi expressed GFP upon ATc treatment once these vacuoles were formed (Fig. 1E), demonstrating that they are transcriptionally active, in agreement with the sustained recovery of viable bacteria after 48 h pi (Fig. 1B).

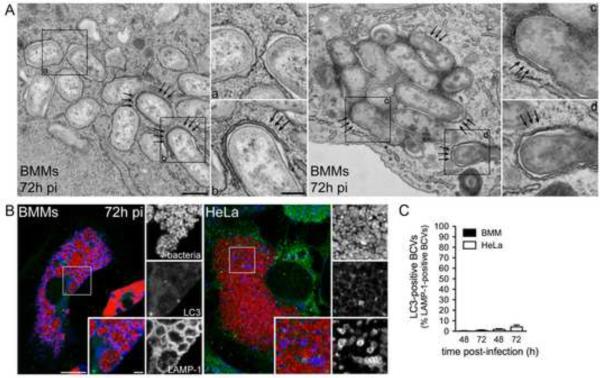

Controlling secondary infections with a low concentration of gentamicin (25 μg/ml) from 24 h pi onwards did not affect the formation of this compartment (Supplemental Information, Fig. S1A–B). Therefore these late endosomal vacuoles do not originate from reinfection events and constitute a post ER replication stage of the bacterium's intracellular cycle. Ultrastructural analysis of these vacuoles revealed that, unlike rBCVs that typically display single, ribosome-laden membranes, (Fig. 2A, inset a) (Celli et al., 2003)), ~ 20% of BCVs at 72 h pi in BMMs (Fig. 3A) were either engulfed by double membrane crescents (Fig. 2A, inset b) or delimited by multiple membranes (Fig. 2A, inset d and Fig. 3A), suggestive of an autophagy process. Double membrane-bound bacterial clusters consistent with large vacuoles (Fig. 1B) were also detected (Fig. 2A, inset c and Supplemental Information, Fig. S2) and their endosomal nature was confirmed by immuno-electron microscopy in both BMMs and Hela cells (72 h pi, Supplemental Information, Fig. S2B). Taken together, these observations indicate that post ER replication, endosomal BCVs display structural features consistent with an autophagic process and were named autophagic BCVs, or aBCVs.

Figure 2.

Late endosomal BCVs display structural features of autophagy, but do not accumulate the autophagy protein LC3. (A) Representative TEM images of BMMs infected with B. abortus 2308 for 72 h. Arrows indicate double membrane structures on BCVs or wrapping around single membrane BCVs. Inset a shows single membrane rBCVs. Insets b,c and d show multimembrane BCVs. Scale bars are 500 and 200 nm. (B) Representative confocal micrographs of BMMs (left-hand panel) or HeLa cells (right-hand panel) infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus 2308 (red) and immunostained for LC3 (green) and LAMP-1 (blue) at 72 h pi. Scale bars are 10 μm and 2 μm. (C) Quantification of late LAMP-1-positive BCVs that accumulated LC3 at 48 and 72 h pi in BMMs (filled bars) and HeLa cells (open bars). Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. See also Figure S2.

Figure 3.

Role of autophagy proteins in Brucella trafficking and aBCV formation. (A) Quantification of LAMP-1-positive BCVs up to 24h in siRNA-depleted HeLa cells. (B) Quantification of aBCV formation at 24, 48, and 72h pi in HeLa cells treated with either non-targeting siRNA (siNT), siBeclin 1, siULK1 or siULK1 and siBeclin 1.(C) Quantification of aBCV formation at 24, 48, and 72h pi in HeLa cells treated with either non-targeting siRNA (siNT), siATG5, siLC3B or siATG7. All data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. (D) Representative confocal micrographs of HeLa cells treated with either non-targeting (siNT) or siULK1+siBeclin1 siRNAs, infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus 2308 (red) and immunostained for LAMP-1 (green) and calnexin (blue) at 72 h pi. Scale bars are 10 and 2 μm. (E) Representative intracellular growth curves of B. abortus 2308 in HeLa cells treated with either non-targeting (siNT) or siULK1+siBeclin1 siRNAs. Data are means ± SEM from a representative experiment performed in triplicate. (F) Representative Western blot analysis of Atg7 and Beclin1 depletion at 0 and 72 h pi in BMMs treated with either non-targeting siRNAs (siNT), siBeclin1, or siATG7. Actin was used as a loading control. (G) Quantification of aBCV formation at 72 h pi in BMMs treated with either non-targeting siRNAs (siNT), siAtg7 or siBeclin1. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. (H) Representative confocal micrographs of C57BL/6J BMMs treated with either non-targeting (siNT), siAtg7 or siBeclin1 siRNAs, infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus 2308 (red) and immunostained for LAMP-1 (green) and calnexin (blue) at 72 h pi. Scale bars are 10 and 2 μm. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (Student's two-tailed t test; P< 0.05). See also Figure S3.

aBCV formation requires the autophagy-associated proteins Beclin1 and ULK1

Given the ultrastructural features of aBCVs, we next examined whether these vacuoles display markers of autophagic membranes. Using LAMP-1 as a marker for aBCVs, we did not detect endogenous LC3 isoforms on these vacuoles in either BMMs or HeLa cells at 48 or 72 h pi (Fig. 2B and C), indicating that their membranes did not accumulate LC3. Despite these results, we examined the potential role of various autophagy proteins in aBCV formation via siRNA-mediated depletion in HeLa cells and first tested whether their depletion affected Brucella trafficking to the ER. Based on LAMP-1 exclusion during biogenesis of rBCVs (Celli et al., 2003; Comerci et al., 2001; Salcedo et al., 2008; Starr et al., 2008), single depletions of either the autophagy elongation proteins ATG5, ATG7, LC3B, or the autophagy initiation proteins Beclin1 or ULK1 (Supplemental Information, Fig. S4A) did not affect eBCV maturation into rBCVs (Fig 3A), although they did prevent rapamycin-induced LC3 lipid conjugation (Supplemental Information, Fig. S3B). This demonstrates that a functional autophagy pathway is not required for Brucella trafficking to the ER. Depletion of either ULK1 or Beclin 1 significantly decreased formation of aBCVs at 48 and 72 h pi, and their combined depletion nearly abolished aBCV formation (Fig. 3B, P< 0.05), despite unaffected intracellular bacterial proliferation (Fig. 3D–E). This indicates that aBCV formation requires functional ULK1 and Beclin 1 autophagy initiation/nucleation complexes and is unrelated to bacterial replication. By contrast, knockdown of either ATG5, ATG7 or LC3B did not impair, but instead potentiated, aBCV formation (Fig. 3C, P< 0.05), indicating that, consistent with the lack of LC3 recruitment to aBCVs (Fig. 2B and C), canonical autophagy elongation complexes are not involved in aBCV formation. To confirm these findings in macrophages, we depleted either Atg7 or Beclin 1 (Fig. 4F–H) and examined aBCV formation at 72 h pi. Compared to a non-targeting (siNT) control, Atg7 depletion did not affect aBCV formation (Fig. 4G–H), yet Beclin 1 depletion significantly reduced this process (Fig. 4G–H). Hence, aBCV formation in macrophages also requires the autophagy nucleation protein Beclin 1, but not the autophagy elongation protein Atg7.

Figure 4.

Atg5, Atg16L1 and Atg4B are not required for aBCV formation. (A) Representative fluorescence confocal and TEM images of C57BL/6J, Atg5flox/flox, Atg5flox/flox-Lyz-Cre, Atg16L1flox/flox, Atg16L1flox/flox-Lyz-Cre and Atg4B −/− BMMs infected with either B. abortus 2308 (TEM) or DsRedm-expressing B. abortus 2308 (red) and immunostained for LAMP-1 (green) andcalreticulin (blue) at 72 h pi. Scale bars are 10 and 2 μm (immunofluorescence) or 500 nm (TEM). Values on electron micrographs represent the percentage of bacteria contained within multimembrane BCVs and the number of bacteria analyzed from two independent experiments. (B) Quantification of LAMP-1-positive BCVs (aBCVs) formation in C57BL/6J, Atg5flox/flox, Atg5flox/flox-Lyz-Cre, Atg16L1flox/flox, Atg16L1flox/flox-Lyz-Cre and Atg4B −/− BMMs infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus 2308 for 72 h. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. See also Figure S4.

aBCV formation is independent of autophagy elongation complexes

To exclude the possibility that the ATG5, ATG7 or LC3B independence of aBCV formation results from residual activity due to incomplete siRNA-mediated depletion, we examined aBCV formation in various autophagy null mutation BMMs. Using either Atg5flox/flox control mice or Atg5flox/flox-Lyz-Cre mice lacking Atg5, Atg16L1flox/flox control mice or Atg16L1flox/flox-Lyz-Cre mice lacking Atg16L1 or Atg4B −/− mice, we first tested whether the absence of these proteins affected Brucella trafficking to the ER. Consistent with our results in HeLa cells, the timing and extent of eBCV to rBCV maturation was indistinguishable in either control C57BL/6J, Atg5flox/flox control or Atg5flox/flox-Lyz-Cre BMMs (Supplemental Information, Fig. S4A and B), demonstrating that Brucella trafficking to the ER is independent of Atg5. Similarly, Brucella trafficking to the ER was unaffected in either Atg16L1flox/flox control Atg16L1flox/flox-Lyz-Cre or Atg4B −/− BMMs (Supplemental Information, Fig. S4C), confirming that Brucella trafficking to the ER is independent of these autophagy proteins. Biogenesis of aBCVs was also not impaired in the absence of either Atg5, Atg16L1 or Atg4B (Fig. 4A and B), since aBCVs formed similarly in either control (C57BL6/J, Atg5flox/flox, Atg16L1flox/flox) or deficient (Atg5flox/flox-Lyz-Cre, Atg16L1flox/flox -Lyz-Cre, Atg4B −/−) BMMs, and was even slightly more pronounced in the null mutation BMMs (Fig. 4B). Furthermore, ultrastructural analysis of aBCVs in Atg5flox/flox-Lyz-Cre, Atg16L1flox/flox -Lyz-Cre and Atg4B −/− BMMs showed aBCVs with closed double or multi-membranes at frequencies comparable to control BMMs (Fig. 4A). Complete formation of aBCVs in the absence of these autophagy elongation proteins in BMMs demonstrates that aBCV formation is an Atg5-, Atg16L1-and Atg4B-independent process.

Altogether, aBCV formation in both macrophages and epitheloid cells depends upon the autophagy-associated proteins Beclin 1 and ULK1 but not the autophagy elongation proteins ATG5, ATG16L1, ATG7, ATG4B and LC3B.

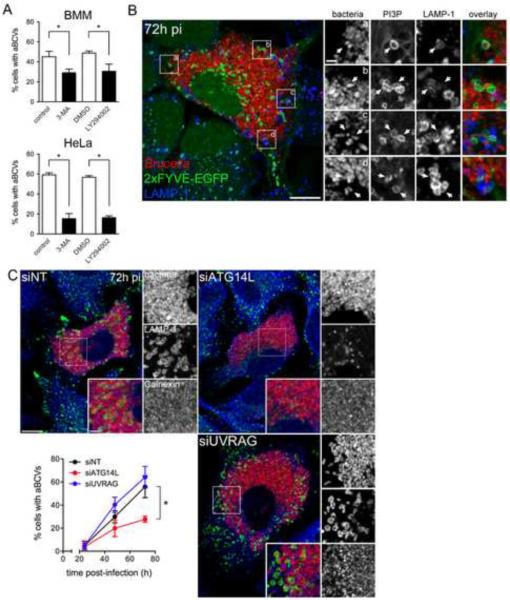

ER-localized Beclin 1-ATG14L complexes are required for aBCV formation

Three Beclin 1-PI3-kinase complexes have been identified that are compartmentalized and fulfill differential functions through their association with the additional subunits ATG14L/Barkor, Rubicon and UVRAG (Itakura et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2008; Matsunaga et al., 2009; Sun et al., 2008). The ATG14L-containing complex localizes to the ER and is required for autophagy initiation (Axe et al., 2008; Itakura et al., 2008; Itakura and Mizushima, 2010; Matsunaga et al., 2010; Matsunaga et al., 2009), while UVRAG-containing complexes localize to Rab9-positive endocytic compartments and modulate autophagosome maturation and endocytic trafficking (Itakura et al., 2008; Liang et al., 2008; Matsunaga et al., 2009; Thoresen et al., 2010; Zhong et al., 2009). Given the ER nature of rBCVs and the requirement of Beclin 1 for the progression of Brucella infection from rBCVs into aBCVs, we tested whether the ER-localized Beclin 1 complex is required for aBCV formation. First, treatment with the class III PI3-kinase inhibitor 3-methyladenine (3-MA) or the PI3-kinase inhibitor LY294002 for 14 h, reduced aBCV formation by ~ 50 and 75% in BMMs and HeLa cells, respectively (Fig. 5A), indicating that aBCV formation depends upon PI3-kinase activity. Furthermore, aBCVs showed recruitment of a 2×FYVE-GFP fusion protein in HeLa cells (Fig. 5B), indicating PI3P generation at sites of aBCV biogenesis. Hence, PI3-kinase activity is detectable at sites of aBCV formation and required for their formation.

Figure 5.

aBCV formation requires PI3-kinase activity and the Beclin1-ATG14L complex. (A) Quantification of aBCV formation in either Brucella infected BMMs (upper panel) or HeLa cells (lower panel) that were either treated with carrier controls (H2O or DMSO), 3-MA (10 mM) orLY294002 (50 μM) for 14 h prior to analysis at 72 h pi. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. (B) Representative confocal micrograph of a HeLa cell expressing the PI3P probe, 2xFYVE-GFP (green), that was infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus 2308(red) for 72 h pi and processed for LAMP-1 immunostaining (blue). Insets are magnifications of the boxed areas on the main image. Scale bars are 10 and 2 μm. (C) Representative confocal micrographs of HeLa cells treated with either non-targeting (siNT), siATG14L or siUVRAG siRNAs that were infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus 2308 (red) for 72 h pi and processed for LAMP-1 immunostaining (blue). Quantification of aBCV formation (middle panel) in HeLa cells treated with either non-targeting (siNT), siATG14L or siUVRAG siRNAs and infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus 2308 (red) for either 24, 48 or 72 h. Data are means + SD from three independent experiments. Asterisks denote statistically significant differences (Student's two-tailed t test; P< 0.05). See also Figure S5.

We next depleted either ATG14L or UVRAG in HeLa cells (Supplemental Information, Fig. S3) to determine which Beclin 1 complex(es) are involved in aBCV formation. Depletion of ATG14L, which prevents targeting of the Beclin 1-VPS34-VPS15 autophagy complex to the ER (Matsunaga et al., 2010), reduced aBCV formation by ~ 45% (Fig. 5C), similar to the effect of Beclin 1 depletion (Fig. 4C). By contrast, depletion of UVRAG did not affect aBCV formation (Fig. 4C), indicating that the endocytic trafficking-associated functions of Beclin 1 complexes do not contribute to aBCV formation. Consistently, depletion of Rab9 also did not affect aBCV formation (Supplemental Information, Fig. S5). Altogether, this demonstrates that the ER localized Beclin 1-PI3-kinase complex is engaged on rBCVs to generate aBCVs, functionally linking the biogenesis of these vacuoles to autophagy initiation.

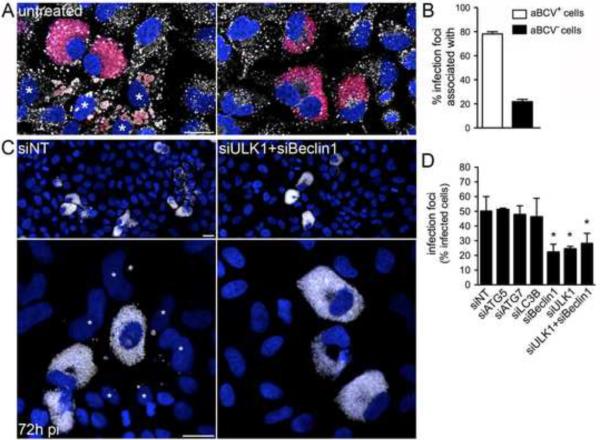

aBCV formation completes the Brucella intracellular cycle and promotes subsequent infections

Given the late occurrence of aBCVs, we tested whether they contribute to completing the bacterium's infectious cycle, by promoting bacterial egress and subsequent infections. Secondary infection events were examined in HeLa cells, in which isolated, infected cells could be monitored for their ability to generate infection foci through subsequent bacterial invasion of neighboring cells. HeLa cells left untreated (data not shown) or treated with non-targeting siRNA (siNT; Fig. 6C) showed that 50 ± 2.8% of highly infected cells generated infection foci by 72 h pi (Fig. 6C–D), indicating that infected cells release infectious bacteria in their vicinity. Most (78 ± 1.9%) of these infection foci were associated with aBCV-containing cells (Fig. 6A–B), correlating aBCV formation with reinfection events. Consistent with aBCV biogenesis, the formation of infection foci was significantly reduced upon depletion of either Beclin1, ULK1 or both proteins (Fig. 6C–D), but not upon depletion of either ATG5, ATG7 or LC3B (Fig. 6D). This indicates that aBCV formation promotes bacterial release and infection of adjacent cells (Supplemental Information, Fig. S6), but does not contribute to bacterial proliferation (Fig. 4E). Hence, aBCV formation allows for the completion of the Brucella intracellular cycle and promotes cell-to-cell spread.

Figure 6.

aBCV formation promotes reinfection events. (A) Representative confocal micrographs of HeLa cells infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus 2308, incubated under reinfection-permissive conditions for 24 h before analysis at 72 h pi, and immunostained for LAMP-1 to detect aBCVs. Asterisks denote reinfected cells neighboring a primary infected cell containingaBCVs (left-hand panel). Infected cells that do not contain aBCVs (right-hand panel) are not associated with infection foci. Bacteria are shown in red, LAMP-1 is pseudocolored in white and DNA is shown in blue. (B) Association of aBCV-containing cells with infection foci. Infection foci were examined for their association with aBCV-containing cells at 72 h pi. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. (C) Representative confocal micrographs of HeLa cells treated with either non-targeting (siNT; left-hand panels) or siULK1+siBeclin1 siRNA (right-hand panels) infected with DsRedm-expressing B. abortus 2308 (pseudocolored in white), incubated under reinfection-permissive conditions for 24 h before analysis at 72 h pi and stained for DAPI (shown in blue). Asterisks denote reinfected cells. Scale bars are 20 μm. (D) Quantification of infection foci at 72 h pi in HeLa cells treated with either non-targeting (siNT), siATG5, siATG7, siLC3B, siBeclin1, siULK1 or siULK1+siBeclin1 siRNAs. Data are means ± SD from three independent experiments. Asterisk denotes a statistically significant difference from the siNT control (Student's two-tailed t test; P< 0.05). See also Figure S6.

Discussion

As a prominent player in intracellular innate immunity, autophagy controls the fate of many intracellular microbes (Levine et al., 2011) through xenophagic capture that involves the canonical, ATG protein-dependent nucleation and elongation machineries originally identified as actors of non selective bulk autophagic degradation (Birmingham et al., 2006; Nakagawa et al., 2004; Ogawa et al., 2005). Similarly, bacterial pathogens that may benefit from autophagy, such as C. burnetii, Y. pestis and Y. pseudotuberculosis, seem to do so by also subverting ATG5- and LC3-dependent processes (Gutierrez et al., 2005; Moreau et al., 2010; Pujol et al., 2009). Hence interactions of pathogens with autophagy generally invoke ATG5- and LC3-dependent autophagy machineries, with the exception of the ATG5-independent capture of cytosolic M. marinum (Collins et al., 2009). Here we uncover a case of bacterial subversion of ULK1-, Beclin 1-and ATG14L-dependent, but ATG5-, ATG4B-, ATG16L1-, ATG7 and LC3B-independent, autophagy-like membrane rearrangements that benefits the infection process of the intracellular pathogen B. abortus.

Previous studies of the Brucella intracellular cycle in epithelial cells have implicated autophagy in its trafficking to the ER (Pizarro-Cerda et al., 1998a; Pizarro-Cerda et al., 1998b). It was recently proposed that the UPR receptor IRE1α promotes Brucella intracellular growth by inducing autophagosome formation at the ER, which in turn promotes BCV fusion with this compartment (Qin et al., 2008). Yet, this model awaits experimental confirmation and the initial evidence for autophagy-dependent Brucella trafficking (Pizarro-Cerda et al., 1998a; Pizarro-Cerda et al., 1998b) lacked the scrutiny of current methods that specifically interrogate this pathway (Mizushima et al., 2010). By examining Brucella trafficking to the ER using either macrophages carrying various null mutations in ATG proteins or HeLa cells depleted of an array of autophagy-associated proteins, we demonstrate here that this bacterium does not require the autophagy proteins ATG5, ATG7, ATG16L1, ATG4B, LC3B, Beclin 1 and ULK1 to generate ER-derived rBCVs, nor does it recruit LC3 on BCVs at any stage (data not shown), clearly ruling out a role for this pathway in Brucella trafficking to the ER in both murine and human cells. Instead, we show that that ULK1- and Beclin1-dependent autophagy nucleation machineries contribute to a post-ER replication stage of the Brucella life cycle, where bacteria generate aBCVs to complete their infectious cycle. The formation of endosomal aBCVs from ER-derived rBCVs is reminiscent of the maturation of Legionella pneumophila-containing vacuoles into acidic, endocytic organelles (Sturgill-Koszycki and Swanson, 2000), since this bacterium also proliferates within ER-derived vacuoles (Swanson and Isberg, 1995). This suggests that pathogens exploiting the secretory pathway may take advantage of common membrane rearrangements exemplified by aBCV biogenesis to (re)enter the endosomal compartment and complete their infectious cycle. The reliance of aBCV formation on nucleation but not elongation complexes indicates that Brucella either partially co-opts the canonical autophagic pathway and uses yet to be uncovered membrane rearrangements to complete rBCV to aBCV conversion, or subverts an autophagic process that is independent of the canonical elongation complexes. Interestingly, depletion of ATG5, ATG7 or LC3B enhanced aBCV formation in HeLa cells, as did null mutations in Atg5, Atg16L1 and Atg4B in BMMs, arguing that autophagy elongation complexes functionally compete with the mechanisms of aBCV formation, possibly along an alternative pathway. Indeed, Nishida et al. recently reported an ATG5/ATG7-independent alternative autophagy-like process that, similarly to aBCV formation, required Beclin 1 and ULK1 and was not associated with LC3 recruitment (Nishida et al., 2009). However, this pathway also depends upon the small GTPase Rab9 (Nishida et al., 2009), yet aBCV formation did not require Rab9 in HeLa cells. Hence, we propose that ER-localized brucellae engage membrane rearrangements dependent upon a subset of autophagy-associated proteins, that may contribute to unconventional xenophagic responses at the ER and possibly other yet to be identified autophagy-related host processes.

The signals that initiate aBCV formation remain to be characterized. Although ER stress can induce autophagy via the UPR (Bernales et al., 2006; Ogata et al., 2006), Brucella infection was not associated with induction of the UPR (data not shown), suggesting this pathway is not triggered upon Brucella proliferation in the ER, or is bacterially inhibited, and likely does not account for aBCV formation. It remains to be determined whether the requirement for ULK1 in aBCV formation links this process to nutrient availability via mTOR (Levine et al., 2011), or whether the ULK1 complex is activated upon different, infection-related signals and detection of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs). The strong association of aBCVs with infection foci indicates that these late vacuoles contribute to bacterial release, either by promoting an exocytic process or through cell death and bacterial egress. While the hypothesis of an exocytic egress requires additional investigation, we did not detect any significant cell death in the Brucella infected cell populations concomitant with aBCV formation (data not shown), consistent with the reported ability of Brucella to prevent programmed cell death in monocytes and epithelial cells (Ferrero et al., 2009; Gross et al., 2000). While future studies should clarify the mechanisms of bacterial release and reinfection, our findings advance our understanding of Brucella intracellular pathogenesis and demonstrate a case of selective subversion of autophagy-associated machineries to the benefit of a bacterial cellular infection process.

Experimental Procedures

Bacterial strains and plasmids

The bacterial strains used in this study were the smooth virulent Brucella abortus strain 2308 and two derivatives expressing either the monomeric red fluorescent protein DsRedm from plasmid pJC44 (Starr et al., 2008), or the green fluorescent protein GFP under the control of the tetracycline-inducible promoter tetA from Tn10 on plasmid pJC45 (see Supplemental Information). All bacteria were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB; Sigma) or on TS agar plates (TSA; Sigma) supplemented with kanamycin (50 μg/ml) to select the pBBR1-MCS2 derivatives pJC44 and pJC45. For infection of eukaryotic cells, 2 ml of TSB were inoculated with a few bacterial colonies from a freshly streaked TSA plate and grown at 37°C to early stationary phase.

Reagents

Antibodies used for immunofluorescence microscopy were: rat anti-mouse LAMP-1 (clone 1D4B, developed by J. T. August and obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank (DSHB) developed under the auspices of the NICHD and maintained by The University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City, IA 52242), mouse anti-human LAMP-1 (clone H4A3, DSHB), rabbit monoclonal anti-Rab7 (clone D95F2, Cell Signaling Technology, Boston, MA), mouse anti-LC3A/B (Clone 4E12; Medical & Biological Laboratories (MBL), Japan), rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3A/B/C (MBL), rabbit polyclonal anti-calnexin (Assay Designs, Ann Arbor, MI), rabbit polyclonal anti-calreticulin (Affinity BioReagents, Golden, CO); Alexa Fluor® 488-donkey anti-mouse, anti-rat, or Cyanin 5-conjugated goat anti-rabbit, anti-mouse (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA). Rabbit polyclonal anti-actin (Bethyl Laboratories, Montogomery, TX), mouse monoclonal anti-GAPDH (Affinity Bioreagents, Rockford, IL), rabbit polyclonal anti-ATG5 (Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-ULK1(R600) (Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-LC3B(D11)XP (Cell Signaling Technology), rabbit anti-ATG7 (Cell Signaling Technology), mouse monoclonal anti-Beclin1 (Abgent, San Diego, CA), rabbit anti-ATG14L (MBL), rabbit anti-UVRAG (Matsunaga et al., 2009); HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG or anti-mouse IgG (1:10,000, Cell Signaling Technology) were used for Western blotting. DAPI and propidium iodide (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) were used as DNA stains. siRNA-mediated knockdown of mammalian proteins was using ON-TARGETplus SMARTpool siRNA (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lafayette, CO) and ON-TARGETplus Non-Targeting Pool siRNA (D-001810) as control. siRNA against human proteins included ATG5 (L-004374), LC3B (L-012846), ATG7 (L-020112), Beclin1 (L-010552), ULK1 (L-005049), ATG14L (KIAA0831, L-020438), UVRAG (L-015465) and mouse proteins included Atg7 (L-049953) and Beclin1 (L-055895).

Cell culture, infections, and determination of bacterial CFUs

BMMs from either C57BL/6J (Jackson Laboratories, Bar Harbor, ME), Atg5flox/flox and Atg5flox/flox-lyz-Cre (Zhao et al., 2008), Atg16L1flox/flox and Atg16L1flox/flox-lyz-Cre (Bruinsma, M. et al., manuscript in preparation) or Atg4B −/− mice (Marino et al., 2010) were harvested and processed as described (Chong et al., 2008). HeLa cells (ATCC clone CCL-2) were cultured as described (Starr et al., 2008). For infections, cells were seeded either on 12mm glass coverslips in 24-well plates (for microscopy; 5×104/well) or 6-well plates (for Western blot analysis; 1.5×105/well) 24 to 48 h prior to infection. Infections were performed as described (Starr et al., 2008), except that cells were maintained in gentamicin-free medium until 24 h, then afterwards in medium containing 25 μg/ml gentamicin to prevent reinfection events, unless specified otherwise. In reinfection experiments, gentamicin was removed at 48 h pi from infected HeLa cells and samples processed at 72 h pi and analyzed for infection foci. These were defined as a cell containing high numbers of bacteria (primary infection) surrounded by at least 4 adjacent cells containing few bacteria (secondary infection). To inhibit PI3-kinase activity, BMMs and HeLa cells were incubated with 3-methyladenine (3-MA; Sigma, St. Louis, MO, 10mM) or LY294002 (Cell Signaling Technology, 50 μM) for 16 h prior to analysis, without any detectable cytotoxicity. To label acidic compartments, BMMs were incubated in presence of 50 nM LysoTracker Red DND-99 (Invitrogen) for 1 h prior to analysis. To label the endocytic compartment, BMMs were incubated in presence of 50 μg/ml Alexa Fluor® 568-conjugated dextran (MW10,000; Invitrogen) for 2 h and immediately analyzed by confocal live-cell imaging. To evaluate intracellular growth, the number of viable intracellular bacteria per well was determined for each time point through enumeration of colony forming units (CFUs) as described (Starr et al., 2008).

Transfections and siRNA mediated depletion of host proteins

A plasmid expressing 2×FYVE-EGFP (pEGFP-2×FYVE, a gift from Dr George Banting (Pattni et al., 2001)) was transfected in HeLa cells 1 day prior to infection using FuGene6™ transfection reagent (Roche) according to the manufacturer's instructions. For siRNA-mediated depletion, HeLa cells were transfected 24 h prior to infection using DharmaFECT1 Transfection Reagent (Dharmacon) with 30–100nM siRNA. BMMs (1.5 × 106 cells) were transfected via nucleofection with 2 μM of siRNA using the Amaxa Biosystems Mouse Macrophage Nucleofector kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland) and a Nucleofector™ II electroporator (program Y-001) 16 h prior to infection. Following nucleofection, cells were plated at 5×104 cells/well (24-well plate) or 4×105 cells/well (12-well plate). Protein depletion was verified at times equivalent to 0 and 72 h pi by Western blotting and densitometry analysis using a Kodak Image Station 4000MM PRO (Eastmann Kodak, Rochester NY).

Microscopy

For immunofluorescence microscopy, infected cells were processed as described (Starr et al., 2008) and samples were observed on a Carl Zeiss AxioImager epi-fluorescence microscope equipped with a Plan Apo 63×/1.4 objective for quantitative analysis, or a Carl Zeiss LSM 710 confocal laser scanning microscope for image acquisition (Carl Zeiss Micro Imaging, Thornwood, NY). Confocal images of 1024 × 1024 pixels were acquired using the Carl Zeiss ZEN 2008 software and assembled using Adobe Photoshop CS3 (Adobe Systems, San Jose, CA). Live cell imaging analysis was performed on a Carl Zeiss MicroImaging LSM 5 LIVE confocal laser scanning microscope equipped with a LCI Plan 63×/1.45 NA objective. Images (768 × 768 pixels) were acquired using 488nm and 561nm solid state lasers for sequential excitation and the Carl Zeiss ZEN 2008 software and were assembled in Adobe Photoshop CS3. Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) was performed as described in Supplemental Information.

Western Blot Analysis

Samples were normalized to total protein concentrations, resolved on SDS-PAGE and transferred to Hybond-ECL nitrocellulose membranes (Amersham Biosciences) as described previously (Chong et al., 2008). Total protein concentration was determined using a BCA protein Assay Kit (Pierce).

Statistical Analysis

A Student's t-test was used to assess statistical differences between two experimental datasets, while multiple comparisons were performed using one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey's test. All values shown, unless otherwise stated, are the mean values ± the standard deviation from three independent experiments.

Supplementary Material

Highlights

Brucella translocates to endosomal vacuoles following replication in the ER.

Brucella selectively co-opts proteins involved in autophagosome nucleation.

Subversion of autophagy by Brucella promotes completion of its infection cycle.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Dr Zijiang Zhao for his assistance in providing bone marrow from ATG5flox/flox and ATG5flox/flox-lyz-Cre mice, and to George Banting, Joyce Karlinsey, Tamotsu Yoshimori, Ed Miao and Leigh Knodler for providing reagents and helpful suggestions. We thank Bob Heinzen and Leigh Knodler for critical reading of the manuscript. This work was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, by grant U54 AI057160 to H. W. Virgin and by the Ministry of Science and Innovation- Spain, FP7 (Microenvimet) and the Botin Foundation to C. López-Otin.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Archambaud C, Salcedo SP, Lelouard H, Devilard E, de Bovis B, Van Rooijen N, Gorvel JP, Malissen B. Contrasting roles of macrophages and dendritic cells in controlling initial pulmonary Brucella infection. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40:3458–3471. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arellano-Reynoso B, Lapaque N, Salcedo S, Briones G, Ciocchini AE, Ugalde R, Moreno E, Moriyon I, Gorvel JP. Cyclic beta-1,2-glucan is a brucella virulence factor required for intracellular survival. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:618–625. doi: 10.1038/ni1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axe EL, Walker SA, Manifava M, Chandra P, Roderick HL, Habermann A, Griffiths G, Ktistakis NT. Autophagosome formation from membrane compartments enriched in phosphatidylinositol 3-phosphate and dynamically connected to the endoplasmic reticulum. J Cell Biol. 2008;182:685–701. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200803137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellaire BH, Roop RM, 2nd, Cardelli JA. Opsonized virulent Brucella abortus replicates within nonacidic, endoplasmic reticulum-negative, LAMP-1-positive phagosomes in human monocytes. Infection and immunity. 2005;73:3702–3713. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.6.3702-3713.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernales S, McDonald KL, Walter P. Autophagy counterbalances endoplasmic reticulum expansion during the unfolded protein response. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e423. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham CL, Canadien V, Gouin E, Troy EB, Yoshimori T, Cossart P, Higgins DE, Brumell JH. Listeria monocytogenes evades killing by autophagy during colonization of host cells. Autophagy. 2007;3:442–451. doi: 10.4161/auto.4450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birmingham CL, Smith AC, Bakowski MA, Yoshimori T, Brumell JH. Autophagy controls Salmonella infection in response to damage to the Salmonella-containing vacuole. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:11374–11383. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509157200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boschiroli ML, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Foulongne V, Michaux-Charachon S, Bourg G, Allardet-Servent A, Cazevieille C, Liautard JP, Ramuz M, O'Callaghan D. The Brucella suis virB operon is induced intracellularly in macrophages. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:1544–1549. doi: 10.1073/pnas.032514299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli J, de Chastellier C, Franchini D-M, Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Gorvel JP. Brucella evades macrophages killing via VirB-dependent sustained interactions with the endoplasmic reticulum. J Exp Med. 2003;198:545–556. doi: 10.1084/jem.20030088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celli J, Salcedo SP, Gorvel JP. Brucella coopts the small GTPase Sar1 for intracellular replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:1673–1678. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0406873102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Checroun C, Wehrly TD, Fischer ER, Hayes SF, Celli J. Autophagy-mediated reentry of Francisella tularensis into the endocytic compartment after cytoplasmic replication. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14578–14583. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601838103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chong A, Wehrly TD, Nair V, Fischer ER, Barker JR, Klose KE, Celli J. The early phagosomal stage of Francisella tularensis determines optimal phagosomal escape and Francisella pathogenicity island protein expression. Infection and immunity. 2008;76:5488–5499. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00682-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins CA, De Maziere A, van Dijk S, Carlsson F, Klumperman J, Brown EJ. Atg5-independent sequestration of ubiquitinated mycobacteria. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000430. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comerci DJ, Martinez-Lorenzo MJ, Sieira R, Gorvel JP, Ugalde RA. Essential role of the VirB machinery in the maturation of the Brucella abortus-containing vacuole. Cell Microbiol. 2001;3:159–168. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2001.00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Jong MF, Sun YH, den Hartigh AB, van Dijl JM, Tsolis RM. Identification of VceA and VceC, two members of the VjbR regulon that are translocated into macrophages by the Brucella type IV secretion system. Mol Microbiol. 2008;70:1378–1396. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2008.06487.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorn BR, Dunn WA, Jr., Progulske-Fox A. Porphyromonas gingivalis traffics to autophagosomes in human coronary artery endothelial cells. Infection and immunity. 2001;69:5698–5708. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.9.5698-5708.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrero MC, Fossati CA, Baldi PC. Smooth Brucella strains invade and replicate in human lung epithelial cells without inducing cell death. Microbes Infect. 2009;11:476–483. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fugier E, Salcedo SP, de Chastellier C, Pophillat M, Muller A, Arce-Gorvel V, Fourquet P, Gorvel JP. The glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and the small GTPase Rab 2 are crucial for Brucella replication. PLoS Pathog. 2009;5:e1000487. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gross A, Terraza A, Ouahrani-Bettache S, Liautard JP, Dornand J. In vitro Brucella suis infection prevents the programmed cell death of human monocytic cells. Infection and immunity. 2000;68:342–351. doi: 10.1128/iai.68.1.342-351.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez MG, Master SS, Singh SB, Taylor GA, Colombo MI, Deretic V. Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell. 2004;119:753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutierrez MG, Vazquez CL, Munafo DB, Zoppino FC, Beron W, Rabinovitch M, Colombo MI. Autophagy induction favours the generation and maturation of the Coxiella-replicative vacuoles. Cell Microbiol. 2005;7:981–993. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2005.00527.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He C, Klionsky DJ. Regulation mechanisms and signaling pathways of autophagy. Annu Rev Genet. 2009;43:67–93. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102808-114910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E, Kishi C, Inoue K, Mizushima N. Beclin 1 forms two distinct phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase complexes with mammalian Atg14 and UVRAG. Mol Biol Cell. 2008;19:5360–5372. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E08-01-0080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Itakura E, Mizushima N. Characterization of autophagosome formation site by a hierarchical analysis of mammalian Atg proteins. Autophagy. 2010;6:764–776. doi: 10.4161/auto.6.6.12709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levine B, Mizushima N, Virgin HW. Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature. 2011;469:323–335. doi: 10.1038/nature09782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liang C, Lee JS, Inn KS, Gack MU, Li Q, Roberts EA, Vergne I, Deretic V, Feng P, Akazawa C, et al. Beclin1-binding UVRAG targets the class C Vps complex to coordinate autophagosome maturation and endocytic trafficking. Nature cell biology. 2008;10:776–787. doi: 10.1038/ncb1740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchesini MI, Herrmann CK, Salcedo SP, Gorvel JP, Comerci DJ. In search of Brucella abortus type IV secretion substrates: screening and identification of four proteins translocated into host cells through VirB system. Cellular microbiology. 2011;13:1261–1274. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2011.01618.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marino G, Fernandez AF, Cabrera S, Lundberg YW, Cabanillas R, Rodriguez F, Salvador-Montoliu N, Vega JA, Germana A, Fueyo A, et al. Autophagy is essential for mouse sense of balance. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:2331–2344. doi: 10.1172/JCI42601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga K, Morita E, Saitoh T, Akira S, Ktistakis NT, Izumi T, Noda T, Yoshimori T. Autophagy requires endoplasmic reticulum targeting of the PI3-kinase complex via Atg14L. J Cell Biol. 2010;190:511–521. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200911141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matsunaga K, Saitoh T, Tabata K, Omori H, Satoh T, Kurotori N, Maejima I, Shirahama-Noda K, Ichimura T, Isobe T, et al. Two Beclin 1-binding proteins, Atg14L and Rubicon, reciprocally regulate autophagy at different stages. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:385–396. doi: 10.1038/ncb1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Yoshimori T, Levine B. Methods in mammalian autophagy research. Cell. 2010;140:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moreau K, Lacas-Gervais S, Fujita N, Sebbane F, Yoshimori T, Simonet M, Lafont F. Autophagosomes can support Yersinia pseudotuberculosis replication in macrophages. Cellular microbiology. 2010;12:1108–1123. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2010.01456.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa I, Amano A, Mizushima N, Yamamoto A, Yamaguchi H, Kamimoto T, Nara A, Funao J, Nakata M, Tsuda K, et al. Autophagy defends cells against invading group A Streptococcus. Science. 2004;306:1037–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.1103966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishida Y, Arakawa S, Fujitani K, Yamaguchi H, Mizuta T, Kanaseki T, Komatsu M, Otsu K, Tsujimoto Y, Shimizu S. Discovery of Atg5/Atg7-independent alternative macroautophagy. Nature. 2009;461:654–658. doi: 10.1038/nature08455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata M, Hino S, Saito A, Morikawa K, Kondo S, Kanemoto S, Murakami T, Taniguchi M, Tanii I, Yoshinaga K, et al. Autophagy is activated for cell survival after endoplasmic reticulum stress. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:9220–9231. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01453-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogawa M, Yoshimori T, Suzuki T, Sagara H, Mizushima N, Sasakawa C. Escape of intracellular Shigella from autophagy. Science. 2005;307:727–731. doi: 10.1126/science.1106036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas G, Akritidis N, Bosilkovski M, Tsianos E. Brucellosis. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2325–2336. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra050570. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pattni K, Jepson M, Stenmark H, Banting G. A PtdIns(3)P-specific probe cycles on and off host cell membranes during Salmonella invasion of mammalian cells. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1636–1642. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00486-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro-Cerda J, Meresse S, Parton RG, van der Goot G, Sola-Landa A, Lopez-Goni I, Moreno E, Gorvel JP. Brucella abortus transits through the autophagic pathway and replicates in the endoplasmic reticulum of nonprofessional phagocytes. Infection and immunity. 1998a;66:5711–5724. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.12.5711-5724.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pizarro-Cerda J, Moreno E, Sanguedolce V, Mege JL, Gorvel JP. Virulent Brucella abortus prevents lysosome fusion and is distributed within autophagosome-like compartments. Infection and immunity. 1998b;66:2387–2392. doi: 10.1128/iai.66.5.2387-2392.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pujol C, Klein KA, Romanov GA, Palmer LE, Cirota C, Zhao Z, Bliska JB. Yersinia pestis can reside in autophagosomes and avoid xenophagy in murine macrophages by preventing vacuole acidification. Infection and immunity. 2009;77:2251–2261. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00068-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin QM, Pei J, Ancona V, Shaw BD, Ficht TA, de Figueiredo P. RNAi screen of endoplasmic reticulum-associated host factors reveals a role for IRE1alpha in supporting Brucella replication. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000110. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rich KA, Burkett C, Webster P. Cytoplasmic bacteria can be targets for autophagy. Cell Microbiol. 2003;5:455–468. doi: 10.1046/j.1462-5822.2003.00292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salcedo SP, Marchesini MI, Lelouard H, Fugier E, Jolly G, Balor S, Muller A, Lapaque N, Demaria O, Alexopoulou L, et al. Brucella control of dendritic cell maturation is dependent on the TIR-containing protein Btp1. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e21. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.0040021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Starr T, Ng TW, Wehrly TD, Knodler LA, Celli J. Brucella intracellular replication requires trafficking through the late endosomal/lysosomal compartment. Traffic (Copenhagen, Denmark) 2008;9:678–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0854.2008.00718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturgill-Koszycki S, Swanson MS. Legionella pneumophila replication vacuoles mature into acidic, endocytic organelles. J Exp Med. 2000;192:1261–1272. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.9.1261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun Q, Fan W, Chen K, Ding X, Chen S, Zhong Q. Identification of Barkor as a mammalian autophagy-specific factor for Beclin 1 and class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:19211–19216. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810452105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson MS, Isberg RR. Association of Legionella pneumophila with the macrophage endoplasmic reticulum. Infection and immunity. 1995;63:3609–3620. doi: 10.1128/iai.63.9.3609-3620.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thoresen SB, Pedersen NM, Liestol K, Stenmark H. A phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase class III sub-complex containing VPS15, VPS34, Beclin 1, UVRAG and BIF-1 regulates cytokinesis and degradative endocytic traffic. Exp Cell Res. 2010;316:3368–3378. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2010.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa Y, Ogawa M, Hain T, Yoshida M, Fukumatsu M, Kim M, Mimuro H, Nakagawa I, Yanagawa T, Ishii T, et al. Listeria monocytogenes ActA-mediated escape from autophagic recognition. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:1233–1240. doi: 10.1038/ncb1967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z, Fux B, Goodwin M, Dunay IR, Strong D, Miller BC, Cadwell K, Delgado MA, Ponpuak M, Green KG, et al. Autophagosome-independent essential function for the autophagy protein Atg5 in cellular immunity to intracellular pathogens. Cell Host Microbe. 2008;4:458–469. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng YT, Shahnazari S, Brech A, Lamark T, Johansen T, Brumell JH. The adaptor protein p62/SQSTM1 targets invading bacteria to the autophagy pathway. J Immunol. 2009;183:5909–5916. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, Wang QJ, Li X, Yan Y, Backer JM, Chait BT, Heintz N, Yue Z. Distinct regulation of autophagic activity by Atg14L and Rubicon associated with Beclin 1-phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase complex. Nature cell biology. 2009;11:468–476. doi: 10.1038/ncb1854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.