Abstract

Purpose

To report a series of patients with Streptococcus endophthalmitis after injection with intravitreal bevacizumab prepared by the same compounding pharmacy.

Design

Non-comparative consecutive case series.

Methods

Medical records and microbiology results of patients who presented with endophthalmitis after injection with intravitreal bevacizumab between July 5 and July 8, 2011, were reviewed.

Results

Twelve patients were identified with endophthalmitis, presenting 1-6 days after receiving an intravitreal injection of bevacizumab. The injections occurred at four different locations in South Florida. All patients received bevacizumab prepared by the same compounding pharmacy. None of the infections originated at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miami, FL, although nine patients presented to its tertiary-care ophthalmic emergency room for treatment, and three additional patients were seen in consultation. All patients were treated initially with a vitreous tap and injection; eight patients subsequently received a vitrectomy. Microbiology cultures for ten patients were positive for Streptococcus mitis/oralis. Seven unused syringes of bevacizumab prepared by the compounding pharmacy at the same time as those prepared for the affected patients also were positive for S. mitis/oralis. After four months of follow-up, all but one patient had count-fingers or worse visual acuity, and three required evisceration or enucleation. Local, state and federal health department officials have been investigating the source of the contamination.

Conclusions

In this outbreak of endophthalmitis after intravitreal bevacizumab injection, Streptococcus mitis/oralis was cultured from the majority of patients and from all unused syringes. Visual outcomes were generally poor. The most likely cause of this outbreak was contamination during syringe preparation by the compounding pharmacy.

Introduction

Over the past six years, the use of vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) inhibitors has become commonplace in the treatment of age-related macular degeneration (AMD), as well as other inflammatory and neovascular retinal diseases, including retinal vein occlusion (RVO) and diabetic macular edema (DME). These agents are injected directly in to the vitreous cavity, and are generally well-tolerated with a low overall complication rate. Endophthalmitis, one of the most feared complications, has previously been reported to have an incidence after intravitreal injection of 0.02% to 0.05%.1,2 In the recently published data from the Comparison of AMD Treatments Trials (CATT) study, 6 cases of endophthalmitis developed after 10,957 intravitreal anti-VEGF injections (0.05%).3

In the current study, an endophthalmitis outbreak is reported after intravitreal injection of bevacizumab (Avastin, Genentech/Roche, South San Francisco, California, USA), a full-length humanized VEGF inhibitor commonly used off-label in the treatment of AMD, RVO, and DME.4 All patients received intravitreal injections of bevacizumab prepared by the same compounding pharmacy in South Florida. This is the largest reported outbreak of infectious endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection of a contaminated group of pre-filled bevacizumab syringes.

Methods

After approval of the Institutional Review Board of the University of Miami, and in cooperation with local and state Departments of Health, the charts of all patients in this outbreak of endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection were retrospectively reviewed.

The data collected include the age and sex of each patient, the affected eye and its lens status, the date of the most recent bevacizumab injection, the underlying diagnosis and clinical indication for intravitreal injection, and the pre-injection visual acuity. Presentation and diagnostic data were recorded as well, including the date of presentation, the visual acuity and intraocular pressure, the pain score, the presenting symptoms and signs, and the initial management as well as the microbiology results. The patients’ clinical courses were recorded, including the visual acuity, the number of antibiotic and steroid injections, the use of pars plana vitrectomy and other surgical interventions, as well as the last recorded visual acuity outcome at four months follow-up.

Results

A total of twelve patients were included in this study, nine actively managed at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, and three seen in consultation although initially managed by outside vitreo-retinal specialists. The average age of patients at the time of presentation was 78.0 years (median 77.3 years, range 68.1-88.2 years). There were 7 women (58%) and 5 men (42%). The indications for treatment with an anti-VEGF agent included neovascular AMD (9 patients; 75%), macular edema (2 patients; 17%), and RVO with neovascular glaucoma (1 patient; 8%). Pre-injection visual acuities ranged from 20/25 to count-fingers.

In this outbreak, the affected patients were injected by four physicians in four separate office locations over a four-day span. All patients received bevacizumab prepared by the same compounding pharmacy. All treating physicians report similar injection preparation techniques, including the use of povidone-iodine and sterile lid speculums. All patients were given a fourth-generation fluoroquinolone topical antibiotic drop (gatifloxacin or moxifloxacin) for post-injection endophthalmitis prophylaxis.

Eleven of the affected patients were members of the same managed care organization (MCO), which contracted with the compounding pharmacy to supply the treating ophthalmologists with pre-filled bevacizumab syringes for each patient. The MCO of the twelfth patient contracted with the same compounding pharmacy for bevacizumab syringe preparation. One patient (case 12) received a bilateral injection of bevacizumab, though the fellow eye was treated with bevacizumab prepared by a different pharmacy.

Patients presented complaining of redness, pain, and decreased visual acuity. Two patients (17%) presented within one day of their injection, six patients (50%) presented on post-injection day two, two patients (17%) presented three days after their injection, and two patients (17%) presented six days after their intravitreal injection. Presenting visual acuities were light perception (eight patients, 67%), hand-motions (2, 17%), count-fingers (1 patient, 8%), and 20/200 (1, 8%). Nine patients (75%) presented with an intraocular pressure greater than 33 by tonopen tonometry, with self-reported pain scores of 8-10 out of 10.

All twelve patients were treated with initial vitreous tap and injection of antibiotics, including intravitreal vancomycin 1.0 mg/0.1 mL. Culture results for ten vitreous specimens were positive for Streptococcus mitis/oralis; susceptibility testing demonstrated that the bacteria were sensitive to vancomycin. Four patients received repeat intravitreal injections of vancomycin and steroids; one of these patients received a second diagnostic vitreous tap as well, which was positive for S. mitis/oralis. Eight patients underwent pars plana vitrectomy, and in six of these cases, the vitreous cassettes were sent for microbiological evaluation; two were culture-positive for S. mitis/oralis. Additionally, two patients underwent evisceration six and eight weeks (cases 5 and 9, respectively) after presentation, and the intraocular contents in one of these cases was culture-positive for S. mitis/oralis. One patient, case 8, had persistent inflammation after vitrectomy surgery, and was subsequently enucleated.

All patients showed marked improvement in their clinical appearance during the days after their initial treatment. Signs and symptoms of improvement included consolidation and contraction of the anterior chamber fibrin, decreased conjunctival injection and chemosis, and increased patient comfort. (See Figures 1-3 for representative examples.) For all but one patient (case 7), the visual acuity remained poor: at four months follow up, five patients were no light perception (42%); four patients (33%) were hand-motions, two (17%) were count-fingers, and one patient (8%) had a visual acuity of 20/25. See Table 1 for a summary of the clinical course.

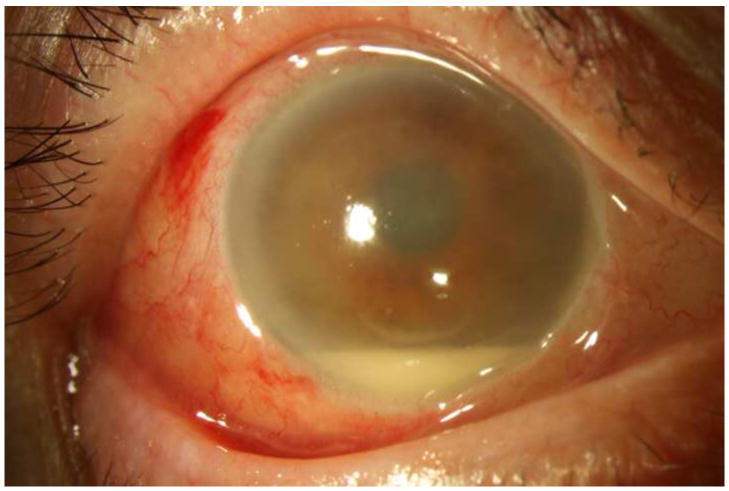

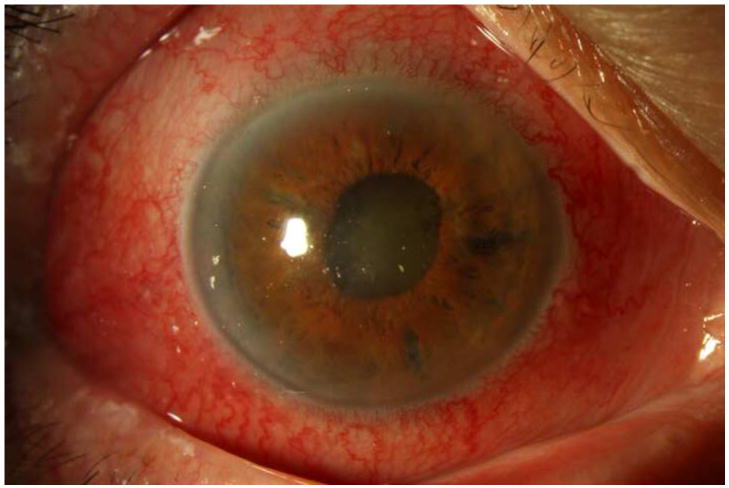

Figure 1. Streptococcus mitis/oralis endophthalmitis case example – improving clinical picture.

Case 2 presented 2 days after intravitreal bevacizumab injection with hand motions vision (left). One week after initial vitreous tap and inject (middle), the hypopyon showed marked contraction, though the vision was light perception. By one month (right), the clinical appearance had improved, but the vision was still light perception. After subsequent vitrectomy, the visual acuity was hand motions.

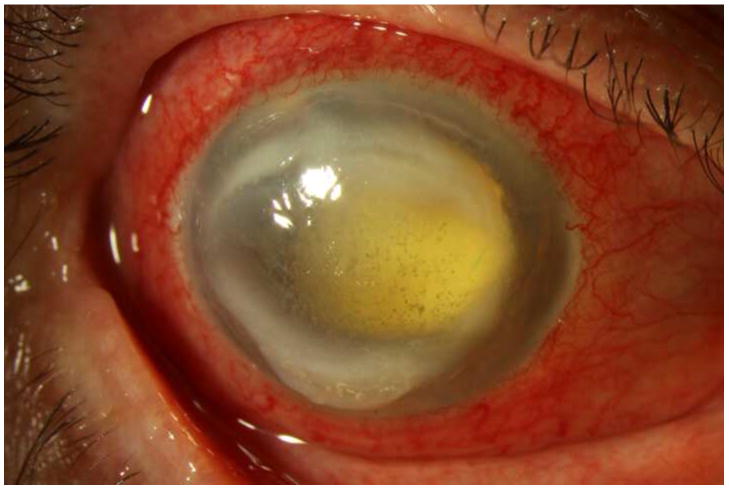

Figure 3. Streptococcus mitis/oralis endophthalmitis case example – eviscerated six weeks after injection.

Case 9 presented 6 days after intravitreal bevacizumab injection with light perception vision (left). One week after initial vitreous tap and inject (middle) the vision had deteriorated to no light perception. At one month (right), the visual acuity was still no light perception; ultimately the patient underwent an evisceration at six weeks after initial presentation.

Table 1.

Summary of patients with Streptococcus endophthalmitis after intravitreal bevacizumab’

| Case | Baseline diagnosis | Preinjection Visual Acuity | Visual Acuity at the Time of Endophthalmitis | Days to Presentation | Initial Treatment | Surgical intervention | Visual Acuity at 4 months |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AMD | 20/400 | LP | 2 | V,C,D | PPV | NLP |

| 2 | CME | 20/100 | HM | 2 | V,C,D | PPV | HM |

| 3 | AMD | 20/30 | LP | 2 | V,C,D | PPV | CF |

| 4 | AMD | 20/400 | LP | 2 | V,C,D | PPV | NLP |

| 5 | AMD | 20/400 | LP | 1 | V,C,D | Ev | NLP |

| 6 | AMD | 20/50 | LP | 1 | V,C,D | PPV | HM |

| 7 | AMD | 20/40 | 20/200 | 3 | V,C,D | 20/25 | |

| 8 | CME | CF | LP | 6 | V,C,D | PPV, Enuc | NLP |

| 9 | VO/NVG | CF | LP | 6 | V,C,D | Ev | NLP |

| 10 | AMD | 20/40 | LP | 3 | V,C | HM | |

| 11 | AMD | 20/25 | CF | 2 | V, A | PPV | HM |

| 12 | AMD | 20/25 | HM | 2 | V, A | PPV | CF |

All culture results were positive for Streptococcus mitis / oralis.

AMD, age-related macular degeneration;CME, cystoid macular edema; VO, vein occlusion; NVG, neovascular glaucoma; NLP, no light perception; LP, light perception; HM, hand motions; CF, count fingers; V, intravitreal vancomycin 1.0 mg/0.1 mL; C, intravitreal ceftazidime 2.25 mg/0.1 mL; A, intravitreal amikacin 0.4 mg/0.1 mL; D, intravitreal dexamethasone 0.4 mg/0.1 mL; PPV, pars plana vitrectomy; Ev, evisceration; Enuc, enucleation

Seven unused bevacizumab syringes prepared by the same compounding pharmacy during this time period were also culture-positive for S. mitis/oralis. Isolates were identified using conventional (phenotypic) techniques. Confirmation and isolate congruency was confirmed with molecular techniques using polymerase chain reaction universal and species-specific primers. All culture results were confirmed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Local and state departments of health, as well as the CDC and Food and Drug Administration (FDA) were contacted and have been investigating the source of the contamination. The results of these investigations are still pending at the time of publication.

Discussion

Endophthalmitis after intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents is a rare event, occurring somewhere between 1 in 2,000 - 5,000 injections in previously reported studies.1,2 Half of cases are culture negative, while those that are culture-positive most commonly grow Staphylococcus and Streptococcus species.1,2

Previous studies have reported poor visual outcomes in Streptococcal endophthalmitis, with 59% - 80% of cases having hand-motions or worse visual acuity.2,5 The outcomes in this case series are consistent with the results of these prior published reports. At four months post-presentation, only one patient (case 7), who had the best vision at presentation, recovered her pre-injection visual acuity.

In this outbreak, four patients had persistent culture-positive endophthalmitis despite initial treatment with intravitreal antibiotics. One patient had a repeat vitreous tap one day after presentation, while the vitrectomy cassettes in two patients who underwent surgery were culture-positive, as were the intraocular contents in one patient who underwent evisceration. This supports previously reported evidence that a single dose of intravitreal antibiotic is not always sufficient to sterilize the vitreous cavity.6

All 12 patients in this series were treated with fourth-generation fluoroquinolone topical drops for post-injection prophylaxis of endophthalmitis. Fluoroquinolone and other anti-infective eye drops are often used for this purpose, although this practice has recently been questioned based on concerns of efficacy, bacterial resistance, and cost.7 The impact of post-injection topical antibiotics in this case series appears to be minimal.

This is the first reported multi-site, multi-physician outbreak of infectious endophthalmitis in the United States after intravitreal injection. Several other outbreaks of endophthalmitis – both infectious and sterile – have occurred in both the United States and abroad associated with contamination by the compounding pharmacy which prepared the syringes. 8-13 These outbreaks are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Summary of reported endophthalmitis outbreaks after intravitreal bevacizumab

| Location | No. of patients | Organism |

|---|---|---|

| Nashville, TN8 | 5 | Alpha-hemolytic Streptococcus |

| Veterans Affairs - Nashville, TN9 | 4 | Not reported |

| Minneapolis, MN (personal communication) | 5 | Coagulase-negative Staphylococcus |

| Veterans Affairs - Sepulveda, CA10 | 5 | Culture negative |

| Miami Dade and Broward Counties, FL (current study) | 12 | Streptococcus mitis/oralis |

| Shanghai, China11, 12 | 80 | Culture negative (counterfeit drug) |

| Seoul, Korea13 | 2 | Serratia marescens |

Almost all of the literature on reducing endophthalmitis rates after intravitreal injection has focused on the peri-injection period, including the use of pre- and post-injection antibiotics, patient preparation with povidone-iodine lid scrubs, sterile lid speculums, and immediate pre-injection povidone-iodine applied directly to the conjunctiva. This attention does not address the importance of the drug preparation, as bevacizumab is distributed in 4- or 16-mL preservative-free, single-use vials, and is aliquoted into smaller doses for intravitreal use.

Pharmacist compliance with the standards outlined in United States Pharmacopeia (USP) chapter 797 is an ideal way to avoid microbial contamination of bevacizumab syringes. These measures include the use of trained and certified staff, personal protective equipment, and a properly operated and certified ISO Class 5 environment.14 The original description of bevacizumab preparation for off-label intravitreal injection15 is still widely regarded as the standard for intravitreal bevacizumab formulation. At the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute compounding pharmacy, all syringes are held in quarantine for 14 days while ten percent of the prepared syringes made from each bevacizumab vial are sent for microbiological testing. To date, over 60,000 syringes have been prepared without an episode of contamination.

A few simple measures to avoid microbial contamination of syringes during preparation include: 1) avoiding contact of the syringe tip/hub with non-sterile environmental surfaces or ungloved fingers, 2) systematically covering syringes with sterile caps as soon as each dose is prepared, and 3) using a device such as a Mini-Spike Dispensing Pin with Security Clips (B-Braun, catalog #DP-1000SC), which enables the compounder to draw out multiple syringes with only one puncture of the rubber stopper while filtering the air that enters the vial.15,16 Additionally, all syringes should be prepared within six hours of the initial vial puncture under ISO class 5 conditions. Any remaining drug in the vial after this time period should be discarded. Longer-term storage of a punctured vial that has been inadvertently contaminated allows for the exponential growth of an organism and increases the risk of significant patient harm.

Additional steps should be taken at the time of injection to mitigate the risk associated with injecting a potentially contaminated drug. The batch number for each intravitreal injection should be recorded, as should a reliable telephone number or means of contact for each patient. Caution should be taken with bilateral injections. The one patient (case 12) to receive a bilateral injection received bevacizumab from a different source and did not develop endophthalmitis in the fellow eye. This outbreak raises the question of whether bevacizumab syringes prepared from two different batches should be used in patients requiring bilateral injections.

Local, state, and federal authorities are currently investigating the source of the contamination in this outbreak. It appears to be isolated to injections occurring between July 5 and July 8, 2011, using syringes prepared at one compounding pharmacy. Further study is warranted to both determine the root cause of this outbreak and to standardize and improve the safe preparation of bevacizumab for intravitreal use.

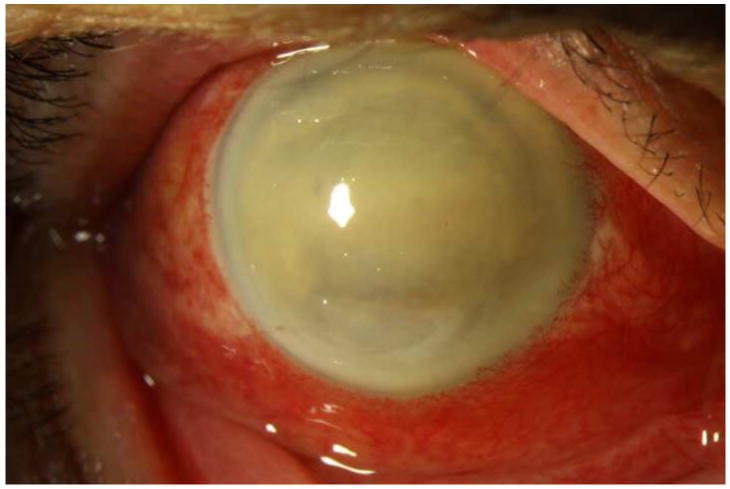

Figure 2. Streptococcus mitis/oralis endophthalmitis case example – prominent ring infiltrate.

Case 8 presented 6 days after intravitreal bevacizumab injection with light perception vision (left). One week after initial vitreous tap and inject (middle), both the corneal ring infiltrate and the anterior chamber fibrin showed signs of contracting. By one month (right), the ring infiltrate had improved and the anterior chamber was nearly clear, though visual acuity was still light perception.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: Financial support was provided by the National Institutes of Health Center P30-EY014801, and an unrestricted grant to the University of Miami from Research to Prevent Blindness, New York, New York.

The Authors wish to acknowledge the support of Thomas J. Török, MD, MPH, and Ann Schmitz, DVM, AM, at the Bureau of Epidemiology at the Florida Department of Health.

Biography

Roger A. Goldberg, MD, MBA, is an ophthalmology resident at the Bascom Palmer Eye Institute, Miami, Florida. He received his undergraduate degree in History from Yale, and spent a year as a Rotary Ambassador of Goodwill studying at the University of Leiden, The Netherlands. After working as a healthcare consultant at McKinsey & Co., he obtained an MD and MBA from Yale. His research interests include healthcare policy, innovation and technology development, and vitreo-retinal surgery.

Footnotes

Contributions of Authors: Design and conduct of study (RAG, HWF, RFI); collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data (RAG, HWF, DM, RFI, SG); preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript (RAG, HWF, RFI, DM, SG).

Financial Disclosures: RAG: none. HWF: Alcon, Allergan. DM: none. SG: none. The authors have no financial or proprietary interests in the material presented herein.

IRB approval was obtained from the University of Miami Human Subjects Research Office to retrospectively review the charts to gather data, which waived the requirement for specific informed consent.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.McCannel CA. Meta-analysis of endophthalmitis following intravitreal injection of anti-VEGF agents: causative organisms and possible prevention strategies. Retina. 2011;31(4):654–661. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31820a67e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moshfeghi AA, Rosenfeld PJ, Flynn HW, Jr, et al. Endophthalmitis after intravitreal anti-vascular endothelial growth factor antagonists: a six-year experience at a university referral center. Retina. 2011;31(4):662–668. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31821067c4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.The CATT Research Group. Ranibizumab and bevacizumab for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(20):1897–1908. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1102673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brechner RJ, Rosenfeld PJ, Babish JD, Caplan S. Pharmacotherapy for Neovascular Age-Related Macular Degeneration: An Analysis of the 100% 2008 Medicare Fee-For-Service Part B Claims File. Am J Ophthalmol. 2011;151(5):887–895. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2010.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Miller JM, Scott IU, Flynn HW, Jr, Smiddy WE, Corey RP, Miller D. Endophthalmitis caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Am J Ophthalmol. 2004;138(2):231–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ajo.2004.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shaarawy A, Grand MG, Meredith TA, Ibanez HE. Persistent Endophthalmitis after Intravitreal Antimicrobial Therapy. Ophthalmology. 1995;102(3):382–387. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(95)31011-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wykoff CC, Flynn HW., Jr Endophthalmitis after Intravitreal Injection: Prevention and Management. Retina. 2011;31(4):633–635. doi: 10.1097/IAE.0b013e31821504f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Frost BA, Kainer MA. Eye Opening: Are Compounding Drugs Causing Harm? Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America 2011 (Poster Presentation) [August 6, 2011]; Available at http://www.ismp.org/docs/paper4263.pdf.

- 9.Wilemon T. Hospital gave tainted shots. The Tennessean. 2011 August 7;:1B, 5B. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pollack A. The New York Times; [September 1, 2011]. Five More Reports of Avastin Injections Causing Blindness. Available at http://www.nytimes.com/2011/09/02/business/more-reports-of-avastin-causing-blindness.html?_r=1&hp. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun X, Xu X, Zhang X. Counterfeit Bevacizumab and Endophthalmitis. N Engl J Med. 2011;365(4):378–379. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1106415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng J-W, Wei R-L. Ranibizumab for age-related macular degeneration. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(6):582. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc1013316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lee SH, Woo SJ, Park KH, et al. Serratia marcescens endophthalmitis associated with intravitreal injections of bevacizumab. Eye. 2010;24(2):226–232. doi: 10.1038/eye.2009.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Revision Bulletin, The United States Pharmacopeia. Rockville, MD: The United States Pharmacopeial Convention; 2008. Chapter <797> Pharmaceutical compounding—sterile preparations; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rich RM, Rosenfeld PJ, Puliafito CA, et al. Short-term safety and efficacy of intravitreal bevacizumab (Avastin) for neovascular age-related macular degeneration. Retina. 2006;26(5):495–511. doi: 10.1097/01.iae.0000225766.75009.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Stucki C, Sautter AM, Favet J, Bonnabry P. Microbial contamination of syringes during preparation: the direct influence of environmental cleanliness and risk manipulation on end-product quality. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2009;66(22):2032–6. doi: 10.2146/ajhp070681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]