SUMMARY

Tissue and organ architectures are incredibly diverse, yet our knowledge of the morphogenetic behaviors that generate them is relatively limited. Recent studies have revealed unexpected mechanisms that drive axis elongation in the Drosophila egg, including an unconventional planar polarity signaling pathway, a distinctive type of morphogenetic movement termed ‘global tissue rotation’, a molecular corset-like role of extracellular matrix, and oscillating basal cellular contractions. We review here what is known about Drosophila egg elongation, compare it to other instances of morphogenesis, and highlight several issues of general developmental relevance.

The problem of tissue morphogenesis

The most captivating aspect of biology to the youngest budding scientist may be the diversity of animal forms. Darwin memorably expressed this sentiment as ‘endless forms most beautiful’ (Darwin, 1859); both external bodies and their internal organ counterparts display wonderful, and wonderfully diverse forms. These forms do not of course exist for our aesthetic appreciation; instead they adhere to the maxim ‘form follows function’. To give just one example, the function of many of our own organs, including vasculature, kidneys, and lungs, depends on the construction of a highly branched network of elongated tubules. In order to understand how organs and indeed organisms function, we need to understand the processes that generate such forms during development.

The mechanisms that drive tissue and organ morphogenesis are subjects of long-standing interest. Embryonic events such as gastrulation and axis extension have been extensively studied, particularly in externally fertilizing animals such as sea urchins, sea squirts, frogs, fish, worms and flies. Despite this diversity, research to date has uncovered a fairly limited but highly conserved repertoire of cell behaviors that mediate morphogenesis (Quintin et al., 2008). For instance, apical constriction of epithelial sheets drives tissue invagination during gastrulation across many species, as well as subsequent developmental events (Sawyer et al., 2010). Similarly, many species utilize convergent extension, in which a group of cells converge along a common midline and intercalate, to elongate the body axis (Keller, 2002). Yet while these are several examples of well-understood processes, our study of animal morphogenesis is really in its infancy. We need to know all the dynamic cellular behaviors that shape tissues, uncover the mechanisms by which these are individually and collectively regulated, and understand how these molecular mechanisms interface with cell and tissue mechanical properties to actually sculpt organs.

Follicle elongation during Drosophila oogenesis

This Perspective will discuss mechanisms that confer the simple oval shape of the Drosophila egg, a relatively unexamined process that is shedding new light on the above issues. Drosophila oogenesis has a long history of study, dating back to the pioneering descriptions of King (King, 1970; King et al., 1956), and has numerous features that render it attractive to developmental biologists (Spradling, 1993). One advantage is the simplicity of the organ. Drosophila eggs arise from individual units called follicles (or egg chambers), which consist of just two cell types, the germline and a surrounding somatic epithelium (Fig. 1C). A germline cyst, which contains 15 supporting nurse cells and a single oocyte, forms the core of each follicle. The cyst is encased within a simple monolayered epithelium of ‘follicle cells’ (FCs); FCs contact the germline at their apical surfaces while their basal surfaces lie along a basement membrane. A second advantage is the anatomical organization of the ovary (Fig. 1A). The stem cell populations that generate the germline and somatic follicle components reside in the anterior of an ovariole; each follicle moves posteriorly as it develops and is separated from neighboring follicles by intervening stalk cells (Fig. 1B). An ovariole contains 6-8 follicles of increasing maturity, vividly illustrating why it can be called an ‘egg assembly line’, and providing snapshots of the ~7.5 days of development between the initial stem cell division and the mature egg. A third advantage is that the rich biology of oogenesis can be investigated with the full power of Drosophila genetics, via both classical female sterile approaches and more contemporary genetic mosaic analyses. These features have made Drosophila oogenesis an important system for the study of diverse biological processes, from DNA replication to pattern formation to stem cell and miRNA biology. By comparison, one of the most visually conspicuous events -how follicles take on their shape—has received little attention.

Figure 1. Drosophila Oogenesis.

(A) Ovariole expressing Collagen-IV-GFP (green), stained for filamentous actin (red), DNA (blue) and FasIII (orange). Stages are marked. Anterior of ovariole is to left and posterior is to right; all subsequent panels share this orientation unless otherwise specified.

(B) Close-up of stalk cells (sc) separating two follicles.

(C) Anterior-posterior axis of the follicle, established during initial stages of oogenesis, is reflected by polar cells (FasIII-GFP,orange) in the epithelium. The oocyte is localized at the posterior. St. 7 follicle is stained as in (A).

(D) Radial symmetry of the follicle at st. 8 demonstrated by slices through the A-P (D’) and circumferential (D”) axes. Indy-GFP (green) marks follicle epithelial plasma membranes.

As a model for morphogenesis, the follicle again offers many attractive features (Horne-Badovinac and Bilder, 2005). First, after leaving the germarium, each follicle is encased in its own basement membrane, and its development can be considered as largely isolated. Second, it has well-defined and restricted periods of cell division. After the 16 cell cyst is formed, the germline grows only through endoreplication of nurse cells, which drive a >5000-fold expansion of follicle volume. Meanwhile, the follicle epithelium proliferates to ~650-1000 cells (measurements vary) by the end of stage 6, when cell divisions cease; afterwards, endoreplication allows continued FC growth (Fig. 2C). Therefore, changes in follicle shape following stage 6 are ‘pure’ morphogenesis, with limited complicating involvement of cell proliferation or death. Third, the follicle is geometrically simple; it is radially symmetric around its anterior-posterior (A-P) axis (Fig. 1D) until dorsal-ventral symmetry is broken at stage 7 (Roth and Lynch, 2009). Indeed, the A-P axis is the early follicle’s only apparent axis, evident in the presence of specialized FCs at each pole of the epithelium, with the oocyte localized to the posterior pole (Figs. 1A,C). Fourth and most critically, the follicle undergoes a sequence of fascinating morphogenetic changes during its development. Some of these (e.g. border cell migration (Montell, 2003; Rorth, 2009), dorsal appendage morphogenesis (Berg, 2008)) have met with substantial previous study; others (e.g. the squamous/columnar transition of cuboidal epithelial cells and their accompanying repositioning with respect to the germline (Grammont, 2007; Kolahi et al., 2009)) less so.

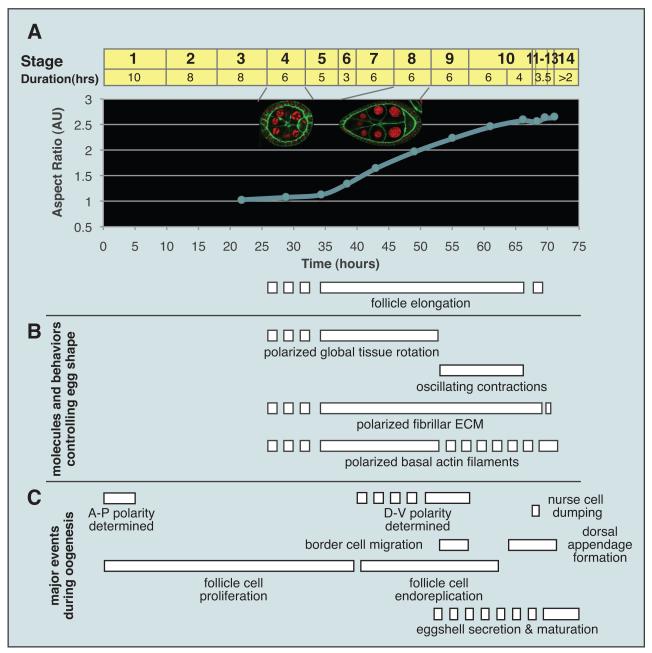

Figure 2. Dynamics of Egg Elongation.

(A) Elongation of follicles, depicted as follicle aspect ratio with respect to developmental time. Stages of oogenesis are marked on top of graph. Insets show st. 4 (isotropic) and st. 8 (elongated) follicles.

(B) Timing of events involved in egg elongation, in comparison to major events of oogenesis (C). Dotted lines indicate process initiated but not mature. See also Horne-Badovinac and Bilder (2005).

In this review we focus on the most obvious morphogenetic change, which is also the simplest: how eggs develop their oval shape. Newly formed follicles are nearly perfect spheres, which appear round in cross-section. As the follicle grows, growth is initially isotropic; st. 4 follicles are nearly as round as their precursors (Figs. 1A, 2A). However, during st. 5, the follicle begins a pronounced elongation, as growth along the A-P axis exceeds that along the axes perpendicular, hereafter referred to as the ‘circumferential axis’ (Bateman et al., 2001; Frydman and Spradling, 2001; Haigo and Bilder, 2011). At stage 7, the follicle is a prolate ellipsoid (in cross-section a fairly regular oval) (Figs. 1A, 2A), a geometry that is also seen in the stage 14 (nearly mature) egg. The follicle elongates~2 fold (~75% of total) in 20 hours between stages 5 and 9, which we refer to as the ‘major phase’ of follicle elongation (Fig. 2A), and by stage 10, it has reached ~2.5 fold. At the end of stage 10, the contents of the nurse cells are transferred rapidly into the oocyte in a process called ‘dumping’ (Mahajan-Miklos and Cooley, 1994); live imaging suggests that the oocyte expands to fill existing follicle dimensions, so dumping primarily determines egg volume rather than follicle shape per se (Lee and Cooley, 2007). Ellipsoid shape represents a solution to maximize volume while passing through a narrow cross-sectional area such as an oviduct (Smart, 1991); indeed, elongation of the Drosophila egg is required for it to travel readily down the oviduct to be fertilized and laid. Moreover, as egg shape prefigures that of the fertilized zygote, it influences the diffusion of embryonic patterning gradients. Overall, the elemental geometric transitions during Drosophila egg elongation provide a simple case of organ morphogenesis.

The follicle epithelium sculpts the growing egg

Through what mechanisms do insect eggs assume an elongated shape? Pioneering investigations were made on the Dipteran gall midge Heteropeza, whose eggs also elongate from spherical to ellipsoid during development. Removal of the follicle epithelium through irradiation, chemical, or mechanical manipulation caused spherical eggs to develop, suggesting a critical role for the epithelium in elongation (Went, 1978; Went and Junquera, 1981). Strikingly, nearly spherical eggs are also produced by Drosophila homozygous for a female sterile mutation isolated by Nusslein-Volhard called kugelei (kug) (Fig. 3E) (Gutzeit et al., 1991) (now known as fat2, see below). The eggs of kug females are both shorter and broader than WT eggs, distinguishing them from small egg mutants that fail to undergo nurse cell dumping and emphasizing that kug induces a specific defect in organ shape. A similar, albeit weaker phenotype is seen in short egg (seg) mutants, and activity of the seg gene product, like kug, appears to be required in the FCs and not the germline (Wieschaus et al., 1981). These data reinforce the notion that egg elongation is determined by activities in the follicle epithelium.

Figure 3. Planar Cell Polarity Phenomena in Follicles.

(A) Planar polarized organization of basal filamentous actin (red) at st. 8. Monopolar protrusions (arrows) reveal coordinated chirality within the tissue.

(B) Appearance of planar polarized stress fibres at st. 12.

(C) Planar polarized organization of Collagen IV (green) at st. 8.

(D) WT elongated egg.

(E) Round egg produced by a fat2 homozygous mutant female.

(F) Round egg produced by a female with mosaic βPS Integrin mutant clones in the follicle epithelium.

(G) Mispolarization of basal actin in fat2 follicle at st. 8. Note signs of local alignment.

(H) Aberrant organization of planar polarized actin in βPS Integrin mosaic epithelium at st. 8. Clone boundaries are marked with dotted line; clone is to top. (I) displays same genotype at st. 12. Note non- autonomous polarity defects in neighboring WT cells.

(J) Diagram of planar polarized actin and Collagen IV localization before (left) and during (right) follicle elongation. In stage 4 follicles, Collagen IV fibrils are nascent and basal actin polarization is poorly coordinated. After stage 5, Collagen IV fibrils elongate in concert with polarized basal actin and monopolar protrusions in FCs. An illustration of the basal surface of a stage 8 FC highlights planar polarized features including monopolar actin-rich protrusions and localized Fat2, as compared to Dlar and βPS Integrin.

Elongation requires links between the ECM and the actin cytoskeleton

The existence of the kug mutation indicated that egg elongation is under simple genetic control. Subsequent, often serendipitous descriptions of additional mutations that disrupt elongation of eggs or follicles -hereafter called ‘round egg mutants’-- confirmed this finding. Some of these mutants, like kug, are homozygous viable but mutant females produce a portion of round eggs, suggesting that egg shape control is a principal role of the gene product. Other mutants show essential requirements in embryonic or larval development, and their role in egg shape is revealed through genetic mosaic analysis (Fig. 3F, H, I). To date, all tested round egg mutants act in FCs rather than the germline.

Interestingly, the molecular identity of genes known to control egg elongation indicates that most act in a single process: linking the extracellular matrix to intracellular actin filaments (Fig. 5D). Extracellular matrix components that are found in the follicle basement membrane include Collagen IV and Laminin; both are required for egg elongation (Frydman and Spradling, 2001; Haigo and Bilder, 2011). Mutations in receptors for these molecules that are expressed on the FC basal surface, including Integrin α and β subunits (Fig. 3F), Dystroglycan, and the receptor tyrosine phosphatase Dlar, also cause the production of round eggs (Bateman et al., 2001; Deng et al., 2003; Duffy et al., 1998; Frydman and Spradling, 2001). Finally, proteins that link these extracellular matrix receptors to the actin cytoskeleton, including the integrin binding protein Talin and the Dystroglycan-binding protein Dystrophin, are required, as is the Pak kinase, which may control actin organization downstream of Dlar and integrins (Becam et al., 2005; Conder et al., 2007; Mirouse et al., 2009). Not all round egg mutants induce identical phenotypes; they vary in the frequency and degree of round eggs produced, and some display round follicles that die prior to egg production. Nevertheless, they collectively indicate that interactions between the actin cytoskeleton within FCs and the basement membrane underlying them are crucial for proper egg shape.

Figure 5. Models of planar polarity propagation in Drosophila.

In the abdomen (A), subtle asymmetries in the number of Ft-Ds heterodimers on each side of a cell result in asymmetric localization of Dachs; whether polarity propagation occurs simultaneously or sequentially is unclear. In the wing (B), molecular interactions between PCP signaling components, both reinforcing (Fz and Vang complexes across cell boundaries) and exclusionary (Fz and Vang complexes within a cell) create a feedback loop that amplifies and coordinates polarity. In the germband (C), planar polarization of actin filaments and Myosin II, along with complementary asymmetries of cell-junction proteins, drive polarized junctional remodeling and cell intercalation. In contrast to these stationary epithelia, in motile FCs (D) mechanotransduction between chirally polarized integrin-mediated adhesion complexes and the extracellular matrix amplifies polarity, while rotation of the epithelium coordinates it. Numbers denote a temporal sequence of events; question marks denote ambiguity in temporal sequence. See text for details.

Planar polarized cytoskeletal organization in the follicle epithelium

Follicle epithelia mutant for the above genes ultimately produce round eggs, but how do these arise? Developmental analyses have generally traced defects back to the major phase of follicle elongation. For follicles lacking Dlar or integrin function, aspect ratios diverge from WT around stage 5; collagen IV mutants diverge slightly later (Bateman et al., 2001; Frydman and Spradling, 2001; Haigo and Bilder, 2011). Analysis of mutant follicles at these stages has revealed that they all share a common phenotype. The follicles that fail to elongate display defects in a striking planar polarized organization of actin filaments on the basal surface of the follicle epithelium (Fig. 3A,B).

Planar polarity refers to the organization of morphological and/or molecular structures within and/or across a tissue in a plane orthogonal to its apicobasal axis (note that this term is meant to be more general than the commonly used ‘planar cell polarity’(Goodrich and Strutt, 2011)). The first description of this organization in Drosophila ovaries came when Gutzeit, following earlier studies on microtubules in Heteropeza, documented basally localized arrays of parallel actin filaments in FCs (Gutzeit, 1990; Tucker and Meats, 1976) that show three aspects of planar polarity. First, all filaments within an individual cell show a common orientation. Second, in all cells this orientation is coordinated; they are aligned around the circumferential axis of the follicle, perpendicular to the elongating A-P axis. Third, on one face along the circumferential axis, filaments in one cell terminate in filopodia-like protrusions that cross over to neighboring cells (Fig. 3A, J). These features, particularly the monopolar protrusions, prompted Gutzeit (Gutzeit, 1992) to term this organization ‘planar circular polarity’; we prefer the term ‘chiral planar polarity’ to distinguish the oriented but continuous planar polarity of the follicle from the more familiar planar polarity seen in bounded tissues.

Planar polarized organization is not apparent when the follicle exits the germarium; consistently oriented basal actin filaments are not visible at st. 4. However, during st. 5 long and thin actin filaments appear along FC basal surfaces, oriented circumferentially, and become increasingly robust until late st. 8 (Fig. 3A, J), after which they become disorganized as the FCs undergo further morphogenetic events (Fig. 2B,C) (Bateman et al., 2001; Delon and Brown, 2009; Frydman and Spradling, 2001; Gutzeit, 1990; He et al., 2010). Planar polarized actin organization reappears transiently at stage 10A and then more stably at stage 12, when filaments in oocyte-contacting FCs form dense polarized bundles that occupy most of basal surface. The latter show striking morphological and molecular resemblances to focal adhesions seen in cell culture (Fig. 3B)(Delon and Brown, 2009).

Does planar polarized actin organization play a role in Drosophila egg elongation? Tucker and Meats initially suggested that mechanical properties of a planar polarized cytoskeleton in insect follicles might constrain growth along the circumferential axis, by providing ‘greater resistance to circumferential expansion than to elongation of the follicle parallel to its polar axis’ (Tucker and Meats, 1976). This model found some favor with subsequent investigators, who termed it a ‘molecular corset’. Experimental support for an actin- based molecular corset came from analyzing ‘round egg’ mutant follicles (Bateman et al., 2001; Conder et al., 2007; Frydman and Spradling, 2001; Gutzeit et al., 1991; Viktorinova et al., 2009). In these, actin filaments retained a common orientation within a given FC, but the orientation in each cell was mispolarized with respect to the follicle axis (Fig. 3G). This loss of polarity is reminiscent of that seen in mutations that disrupt planar polarity in widely studied systems such as the fly wing and vertebrate inner ear (Axelrod, 2009; Goodrich and Strutt, 2011) where polarity is controlled by genes such as frizzled, dishevelled, fat and dachsous (which we call here the ‘conventional PCP signaling pathways’, Figs. 5A, B). Other resemblances suggested a link between the two phenomena. For instance, planar polarity in ‘round egg’ mutant follicles is not random but appears influenced by neighboring cells, with signs of swirls and regional organization. Moreover, mosaic analysis shows that a patch of such mutant FCs can non-cell- autonomously alter the polarity of WT neighbors (Fig. 3H, I) (Bateman et al., 2001; Frydman and Spradling, 2001; Viktorinova et al., 2009).

Despite the several similarities between planar polarity in the follicle and in more familiar planar polarized systems, there are also notable differences. Though both can regulate the polarization of actin-based structures within the plane of an epithelium, conventional PCP signaling often controls actin at the apical surface while in the follicle polarity is manifested at the basal surface. Mutations that disrupt conventional PCP signaling show cell-autonomous phenotypes in clones of cells; there is little non-autonomous rescue. By contrast, small clones of round egg mutant cells can show no disruption of polarity, while large clones do. Finally, mutations that disrupt conventional PCP regulators such as Dishevelled, Van Gogh, Fat and Dachsous have no apparent effect on follicle actin organization or elongation (Viktorinova et al., 2009), suggesting that a different molecular pathway is involved in controlling planar polarity in the follicle.

Fat2 points to an alternate pathway for follicle planar polarity

Potential insight into an alternative follicle planar polarity pathway has come from the recent identification of a new egg elongation regulator (Viktorinova et al., 2009). Fat2 encodes a large atypical cadherin that is related to Fat, an important regulator of conventional PCP signaling in fly wings, eyes, and abdomen. Reverse genetic analysis of using small chromosomal deletions revealed that flies lacking Fat2 are viable but female sterile, and only produce round eggs, similar to kug mutants (Fig. 3E). In fact, kug mutants are allelic to fat2 mutants, and contain premature stop codons in the fat2 coding sequence. Fat2 has a complex expression pattern and can be found at apical and lateral surfaces of the FCs, but at the basal surface a monopolar, chiral localization can be observed during stages 6 and 7: Fat2 is enriched at a single, circumferential side of each FC, where it colocalizes with Dlar (Fig. 3J). In Dlar mutant follicles with misoriented actin filaments, monopolar localization of Fat2 is lost and it is found throughout the plasma membrane.

The identification of a Fat-like cadherin that controls planar organization in the follicle is a fascinating finding, given the precedent in the wing, where heterophilic binding between Fat and its partner Dachsous promotes the polarization of the intercellular contact that leads to planar polarity (Axelrod, 2009; Goodrich and Strutt, 2011; Matakatsu and Blair, 2004). In view of the structure, localization, and mutant phenotype of fat2, along with the independence of follicle planar polarity from conventional PCP signaling, it is tempting to speculate that Fat2 reveals a distinct but partially molecularly analogous pathway for this alternative polarity system. Little is known about vertebrate homologs of Drosophila Fat2, though one, called Fat1, has been implicated in organizing polarized actin structures in migrating cells as well as in podocytes of the kidney (Ciani et al., 2003; Hou et al., 2006; Moeller et al., 2004; Tanoue and Takeichi, 2004). Unlike the other egg elongation regulators, Fat2 does not yet have molecular associations with ECM; it may point to a role for intercellular communication in planar polarity within the follicle (Viktorinova et al., 2011).

Elongation requires rotation of the follicle

While the above round egg mutants identify genes required for follicle elongation, the mechanism through which they do so was unknown. We recently used live imaging of follicles to determine this mechanism, and discovered an unanticipated morphogenetic behavior (Haigo and Bilder, 2011). During the major phase of elongation, the entire follicle executes several complete rotations around its circumferential axis (Fig. 4A). Both the orientation and the timing of rotation coincide with the basal actin planar polarity observed in fixed tissue; rotation is evident at st. 5 but ceases early in st. 9 (Fig. 2B). Both epithelium and germline rotate in concert; they do so within the relatively static basement membrane that encases each follicle (Fig. 4C). Rotation is an active process autonomous to each follicle, as isolated follicles rotate with characteristics similar to those in intact ovarioles. Despite the fact that follicle rotation is robust, with rates averaging ~ 0.5 um/minute, and occurs for more than 20 hours, previous analyses of fixed samples raised no suspicion that any such movement was happening. Because of the topologically closed geometry of the follicle, each intermediate ‘snapshot’ during rotation looks identical; discovery of rotation awaited the advent of conditions for live imaging. Indeed, early films of easily cultured Heteropeza follicles suggested that a similar rotation occurs (Fux et al., 1978).

Figure 4. Polarized Rotation During Follicle Elongation.

(A) Live imaging of rotating st. 7 follicle at different time points. Volocity-rendered 3D image; marked cells are pseudocolored.

(B) Still image stained as in 1A emphasizing that neighboring follicles can rotate with opposite chiralities.

(C) Drawing of basal surface of a rotating follicle, illustrating movement of FCs over stationary ECM fibrils.

(D-F) Models for behaviors associated with elongating follicles: tissue rotation organizing a planar polarized collagen corset that channels growth along the A-P axis (D), oscillating contractions providing further force resistance in the follicle center (E), and collagen corset maintaining anisotropic forces that have driven egg elongation (F). Fig. 4D was modified from Haigo and Bilder (2011).

What are the forces that generate rotation, and why does the follicle undergo this remarkable migration that nonetheless results in no net translocation of the tissue? The coincident timing of follicle rotation, the initial stage of planar polarized actin organization, and the major phase of elongation prompted an investigation of round egg mutants. Follicle epithelia lacking either Integrin or Collagen IV not only fail to elongate but also fail in rotation, indicating that the epithelium is the force-generating tissue and crawls across the follicular basement membrane. This analysis also demonstrated that one function of rotation is to build a planar polarized organization of this basement membrane. Polarized organization of the ECM parallels that of basal actin, becoming clear at st. 5, but is maintained at later stages when basal actin is dynamically reorganized (Figs. 2B, 3C). Moreover, planar ECM polarity is lost in non-rotating mutants. Thus, secretion of components from the circumferentially rotating FCs creates a circumferentially polarized ECM (Fig. 4D). This structure is not only required to permit polarized rotation but also to maintain the elongated shape of the follicle after rotation has ceased (Fig. 4F). The rapid return towards roundness following acute treatment of elongated follicles with collagenase but not actin depolymerizing agents indicates that the planar polarized basement membrane, rather than the basal actin filaments, serves as the molecular corset that imposes the egg’s oval shape and provides a mechanism linking this unexpected morphogenetic movement to the process of egg elongation.

The involvement of planar polarity and tissue rotation in egg elongation raises a host of interesting questions; we consider below four that have general implications for developmental biology.

Does rotation drive elongation of other organs?

Follicle rotation displays hallmarks common to known morphogenetic movements but additionally includes a number of distinguishing features. For instance, it has some resemblance to the most familiar cell behavior driving tissue elongation, convergent extension (Keller, 2002). In both cases, movement of cells transverse to the A-P axis drives elongation. The duration and degree of elongation during follicle rotation (~2 fold over 20 hours) resemble classic convergent extension cases such as Xenopus gastrulation and neurulation (~2-fold over 13.5 hours). As in Drosophila follicles, Xenopus neural plate cells extend planar polarized monopolar protrusions and move along ECM substrates that themselves can show polarized organization (Davidson et al., 2004; Elul and Keller, 2000; Rozario and DeSimone, 2010). However, tissues undergoing convergent extension narrow along one axis while lengthening the perpendicular axis via intercalation of cells. In the follicle, growth increases the length of both axes but is channeled anisotropically; it is not yet clear the extent to which cell intercalation is involved in elongation. Moreover, convergent extension involves cells converging along defined boundaries, while the follicle epithelium is radially symmetric until dorsoventral (D-V) symmetry is broken at st. 7 and lacks an evident boundary for convergence. Many cases of vertebrate convergent extension require conventional PCP signaling, while others such as the rapid fast-phase of Drosophila germband extension (~2-fold elongation over 30 minutes) use actomyosin-based remodeling of adherens junctions to drive intercalation (Cavey and Lecuit, 2009; Vichas and Zallen, 2011); neither of these appears to be the primary mechanism driving follicle elongation. Finally, as an unbounded tissue, rotating follicles lack the intrinsic front-rear polarizing cue inherent to cell groups that migrate with a free or leading edge. Although FCs acquire clear front-rear polarity that is chirally organized within the follicle, they must select and coordinate this direction of motility through alternative, currently mysterious means (see below). Thus, follicle rotation is a distinct form of collective cell migration, in which global rotation of a continuous tissue induces morphogenetic change.

Could tissue rotation drive elongation of other developing organs, including those of vertebrates? It is worth noting that in terms of cell biology, follicle rotation appears to be a fairly traditional migration of an epithelial sheet, maintaining apical cell-cell junctions and using basal cell-matrix interactions to generate a motile force (Friedl and Gilmour, 2009; Rorth, 2009). What is unconventional is the geometry of the migration, in that it is a rotary movement of a topologically closed tissue. While such isolated structures are not common in most animal organs, tubes and cysts with a continuous circumferential axis are widespread, and in glandular organs these are often connected to a spherical cyst-like acinus. An appealing place to look for tissue rotation may therefore be in the development of tubular and acinar organs such as breast, lung and kidney; perhaps in addition to the translational component obvious from fixed samples there is a rotational component during elongation. Additional hints might come from careful analysis of mice mutant for Fat1, an apparent homolog of fly Fat2; these mice have a documented defect in podocyte formation, but other additional phenotypes may be present (Ciani et al., 2003). A third hint is to look for tissues where planar polarized organization of the basement membrane/ECM is known. As live imaging is brought to bear on vertebrate organogenesis, additional instances may come to light.

Although in vivo documentation is yet to come, a recent paper provides intriguing evidence that a tissue rotation-like phenomenon may also occur in human organs. When cultured ex vivo in a basement membrane analog, single primary human mammary epithelial cells or their non-malignant, immortalized counterparts will undergo 3D morphogenesis, recapitulating many stages of normal mammary development to form an acinar-like structure, the apical surface of which faces a hollow lumen and whose basal surface contacts the basement membrane (Petersen et al., 1992). Tanner et al. (Tanner et al., 2011) now reveal that both the single cell progenitor, as well as its cohesive multicellular descendant clusters, show coordinated rotational movement. The mammary cell units undergo multiple revolutions during the process of acinar development, moving at a velocity of ~0.2 um/min with no net translocation. Individual cells show planarly asymmetric enrichment of actin at their basal surfaces in the direction of rotation, and pharmacological treatments demonstrate that actomyosin is required. The chirality of rotation, as well as its plane, appear unconstrained in this isolated system, but rotation occurs constantly over the more than 6 days examined.

Interestingly, malignant mammary cells that cannot organize acini, due to inappropriate interactions with the basement membrane (Weaver et al., 1997), are defective in rotation. The malignant progenitor cell actually spins more quickly as compared to a non-malignant progenitor, but as a multicellular structure develops, coordinated motility between the cells is lost, cells move primarily with random and lateral vectors, and the net structure fails to rotate. This aspect of the malignant phenotype is traced to a loss of cell-cell adhesion: silencing of E- cadherin and Par-3 in non-malignant cells disrupts both coordinated rotation and acquisition of acinar architecture, while reacquisition of polarity (through ‘phenotypic reversion’ of malignant cells (Weaver et al., 1997)) restores both features. The cause-and-effect relationship between coordinated multicellular rotation, cell and tissue polarity, and acinar architecture remains to be determined, as does how the ex vivo rotation of isolated epithelial acini manifests itself in vivo in the context of connecting ducts and other cells. Nonetheless, this work, along with earlier hints of rotation in kidney-derived cysts in cell culture (Guo et al., 2008; Zeng et al., 2006), supports the hypothesis that tissue rotation is a widespread morphogenetic movement reutilized in different developmental contexts.

How is chiral symmetry broken?

The Drosophila follicle has been an important system for understanding both cell and organismal polarity. A rich mechanistic and conceptual framework for symmetry-breaking events that dictate the A-P and later D-V axes exists (Roth and Lynch, 2009); the discovery of chiral planar polarity poses the challenge of understanding the source of this additional break of symmetry. In orienting basal actin filaments and undergoing rotation, the follicle has to define a polarity around its circumference that was previously not appreciated. An individual follicle rotates in a single direction, either clockwise or counterclockwise if viewed along the A-P axis with anterior pole nearest (Fig. 4B). The former can be said to possess dextral chiral polarity, and the latter to possess sinistral chiral polarity, as opposed to the proximodistal, mediolateral or radial polarity evident in bounded epithelial sheets. The polarity of each follicle appears autonomous, with no obvious relationship between its polarity and that of its neighbors. While required for elongation, rotation in either chirality will serve to produce oval eggs, and unlike other symmetry-breaking events, the choice has no apparent ramifications for development of the resultant embryo.

Examples of chiral polarity in biology include snail embryos, where the pattern of cell divisions initiates a conserved L-R signaling pathway that establishes an animal with a given handedness (Kuroda et al., 2009) and the C. elegans embryo, where chiral rearrangements of cells result from and elaborate L-R asymmetry (Pohl and Bao, 2010). Drosophila itself exhibits several instances of chiral rotation: the chiral rotation of the male genitalia, whose directionality is controlled by a myosin that also controls embryonic L-R asymmetry (Speder et al., 2006), and the chiral rotation of ommatidia in the developing eye, which is coordinated by conventional PCP signaling (Jenny, 2010); additionally, chiral biases in the shape of embryonic hindgut cells contributes to the leftward rotation and subsequent rightward looping of this organ (Taniguchi et al., 2011). While chirality in the above cases is invariant, one of many distinguishing features of the follicle is that its chirality is not fixed. The roughly equal proportions of dextrally and sinistrally polarized follicles raise the possibility that the underlying mechanism may involve a stochastic process, which is unusual but not unprecedented (Johnston and Desplan, 2010). How does the entire FC epithelium appreciate the chiral choice; does a planar polarizing signal originate in a particular subset of cells and then propagate, or does the epithelium make some type of collective decision? This is one of many questions whose answers await further study.

What alternative mechanisms can generate planar polarity?

Although less morphologically obvious than apicobasal polarity, planar polarity is being documented in an increasing number of epithelial tissues. Planar polarity information is critical to orient a tissue along a body axis, and to coordinate morphological structures in static tissue as well as collective cell behaviors in dynamic tissue (Zallen, 2007). The importance of planar polarized organization has become clear from studies of animals mutant for conventional PCP pathway regulators. Conventional PCP signaling involves pathways mediated by two groups of proteins, the Fat/Dachsous protocadherins and the Frizzled/Van Gogh module, which is sometimes referred to as the ‘core PCP pathway’ or ‘non-canonical Wnt signaling’. These pathways have numerous tissue- and organism-specific variations and can also interact with each other (for reviews see (Axelrod, 2009; Goodrich and Strutt, 2011)). Current models indicate that Fat and Dachsous bind heterophilically, and that graded spatial expression of Dachsous and the interaction-modifying kinase Four-jointed within a field of cells leads to different levels of Fat- Dachsous heterodimers on an individual cell’s proximal and distal surfaces (Fig. 5A). In Frizzled/Van Gogh signaling, an inter-and intra-cellular feedback mechanism leads to asymmetric localization of these two transmembrane proteins, thus polarizing an intracellular contact by accumulating Dsh on the distal side and Prickle on the proximal side (Fig. 5B). Defects in either pathway can lead to failures of not only orientation of external sensory structures such as hairs and bristles, but also defects in convergent extension, oriented cell divisions and ciliary organization amongst others (Wallingford and Mitchell, 2011; Zallen, 2007).

Despite these impressive phenotypes, some tissues with planar polarity exist in which phenotypes are not seen in conventional PCP mutant animals. The best-characterized example is the Drosophila embryonic germband, another tissue that undergoes extensive elongation through convergent extension(Cavey and Lecuit, 2009; Vichas and Zallen, 2011). In response to embryonic A-P patterning cues, ectodermal epithelial cells polarize Myosin II and Rho kinase to A-P cell interfaces, and Bazooka to D-V interfaces(Bertet et al., 2004; Zallen and Wieschaus, 2004). The resultant localized myosin contractility remodels adherens junctions and their associated actin cytoskeleton, leading to cell shape changes and ultimately polarized cell intercalation (Fig. 5C). No role for conventional PCP signaling in reading or executing this polarity has been uncovered. Moreover, evidence for the conventional PCP pathway in planar- polarized collective cell migration movements such as wound healing (Caddy et al., 2010) and the zebrafish lateral line is limited. Given the apparent prevalence of planar polarized organization, and the existence of planar polarized processes that are not disrupted by mutations in conventional PCP regulators, it seems clear that alternative mechanisms can mediate cell communication.

Follicle planar polarity, which is independent of the conventional PCP pathway, provides another system in which to explore these. One model for follicle planar polarity invokes mechanotransduction in the plane of the epithelium as a primary mechanism (Fig. 5D). In this model, FCs migrating during rotation generate contractile forces on the basement membrane, stimulating and aligning nascent ECM fibrilogenesis. The subsequent increased ECM rigidity is then reciprocally sensed by integrin-mediated adhesions in FCs to reinforce actin filament polarity. In a thematic parallel to conventional PCP signaling (Axelrod, 2009) (Fig. 5B,), this positive biomechanical feedback loop (Parsons et al., 2010) serves to amplify the planar polarized axis. Meanwhile, the concerted migration of the epithelium in the topologically closed follicle results in individual cells moving over ECM fibrils that were previously oriented by its neighbors, thus ensuring global coordination of polarity. When rotation does not occur, basal actin filaments within wild type cells align locally but cannot achieve a uniform global orientation. This model provides one explanation for the role of actin/ECM regulators in follicle planar polarity, but more conventional intercellular signaling roles of proteins such as Fat2 cannot be ruled out. Intriguingly, several groups have recently shown that mechanical force can influence and reorient conventional PCP features (Aigouy et al., 2010; Olguin et al., 2011). Deciphering interactions between the systems controlling global and local cues in follicle planar polarity will shed light on alternative mechanisms that can endow structural and functional planar polarization on both static and dynamic animal epithelia.

How can polarized ECM shape tissues?

The planar polarized ECM that is established by follicle rotation is required to maintain elongation of the egg even after rotation has ceased. The simplest model suggests that the coordinated orientation of ECM fibrils imparts a tensile strength along the circumferential axis that offers a greater resistance to the expansionary forces of the growing follicle during its ~250- fold increase in volume following stage 4, thereby channeling growth along the AP axis (Fig. 4D). Interesting precedents for a mechanical role for polarized ECM in determining tissue shape exist. In plant cells, cellulose is deposited by biosynthetic complexes that are propelled circumferentially through the plasma membrane; the resultant hoop-like cellulose microfibrils in the cell wall constrain elongation of the growing cells within, thus directing growth to the longitudinal axis (Baskin, 2005; Paredez et al., 2006). Recent papers document analogous findings in rod-shaped bacteria: MreB-containing complexes rotate circumferentially around the long cell axis while synthesizing peptidoglycan in the cell wall; this process is required to resist intracellular turgor pressure and maintain cell shape (Dominguez-Escobar et al., 2011; Garner et al., 2011; van Teeffelen et al., 2011). In Xenopus, the orientation of fibronectin fibrils in the ECM surrounding the growing notochord has been suggested to limit the shape changes permitted, determining whether either elongation or widening results (Adams et al., 1990; Koehl et al., 2000). Such data point to a critical role for not just composition but specific planar polarized organization of the ECM in directing cell and organ growth.

How a tissue achieves a specific organization of ECM is not well understood. Several interesting facets have been uncovered. Conventional PCP genes have been implicated in dictating the appropriate tissue plane at which an ECM is formed (Goto et al., 2005). Mechanical forces, either isotropic in static cells or tractile in migratory cells, can orient and remodel existing ECM molecules and assemble ECM polymers and fibrils (Parsons et al., 2010; Rozario and DeSimone, 2010). Indeed, collective cell migration often alters the ECM substrate that is being traversed (Friedl and Gilmour, 2009); the treadmill-like nature of follicle rotation may form a closed-circuit feedback loop that coordinates and reinforces such alterations (see above). Close studies of the ECM-organizing mechanisms in the follicle may reveal principles that will inform not only organ shape but also events such as invasive trajectories of tumor cells.

Oscillating contractions of the FCs contribute to elongation

Follicle rotation ceases before the egg fully elongates, and mutants that block rotation do not entirely block elongation, indicating that several mechanisms combine to regulate the shape of the follicle and resultant egg. Live imaging has revealed another surprising behavior in developing follicles that influences follicle dimensions (He et al., 2010). At stage 9 following the end of rotation (Fig. 2B), the basal but not apical surfaces of certain, primarily centrally located FCs initiate rhythmic though asynchronous contractions. These contractions show planar polarized behavior: Myosin II accumulation on the planar polarized basal actin filaments that were established during rotation leads the cells to shorten along the circumferential but not the AP axis (Fig. 4E). This cell shape change is temporary and is lost between contraction cycles. Nevertheless, acute disruption of actin in follicles undergoing oscillating contractions causes a decrease in follicle width, while increasing contractions via addition of the calcium ionophore ionomycin caused an increase. Depletion of ROCK and Talin produced round eggs (cf (Becam et al., 2005)) and decreased Myosin II recruitment, while overexpression of Paxillin caused egg hyperelongation and increased Myosin II recruitment, suggesting that cell-matrix adhesion and the resultant intracellular tension induces the recruitment of Myosin II to the planar polarized basal actin. The contractions are suggested to serve as a feature of the molecular corset, perhaps dynamically resisting forces in the centre of the egg chamber and directing them towards the poles. This fascinating behavior raises a host of questions concerning the source of the contractions, determinants of their periodicity and spatial distribution, and their exact mechanism in influencing tissue shape. Moreover, it emphasizes that much rich biology remains to be discovered in the visually straightforward morphogenesis of the Drosophila egg.

Oscillating contractions of actomyosin, first described in C. elegans embryos (Munro et al., 2004), have been documented not only in Drosophila follicles but at numerous phases of epithelial morphogenesis in Drosophila embryos. Oscillating contractions in the apical surface of the developing mesoderm are mechanically coupled to adherens junctions via a ratchet-like mechanism; this leads to a permanent cell shape change, inducing apical constriction to drive gastrulation (Martin et al., 2009). Later in development, similar adherens junction-coupled oscillations in the amnioserosa lead to apical constriction that promotes dorsal closure (David et al., 2010; Gorfinkiel et al., 2009; Solon et al., 2009). Oscillations are not however limited to cells undergoing apical constriction. Oscillations also occur in ectodermal cells during germband elongation (Fernandez-Gonzalez and Zallen, 2011; Rauzi et al., 2010; Sawyer et al., 2011) where oscillating Myosin II resolves preferentially in a planar polarized fashion, towards the shrinking adherens junctions that drive cell intercalation. The observation of related phenomena in Xenopus tissues undergoing convergent extension (Kim and Davidson, 2011), where contractions become polarized in elongating cells, suggests that this is a surprisingly widespread and conserved mechanism associated with cell shape change and tissue morphogenesis.

As with tissue rotation and convergent extension, the oscillations in the follicle share similarities and differences with the above processes. The periodic nature, prominence in epithelial cells, and association with tissue morphogenesis are shared. However, in the follicle, it is a basal actomyosin network rather than an apical one that undergoes contractions. In fly embryonic epithelia, this apical network is meshlike and is often mechanically coupled to adherens junctions, while in the follicle it is associated with the lengthy planar polarized actin filaments that are coupled to the extracellular matrix. The apical contractions can be sensitive to planar polarized cues: in the ectoderm, oscillations become biased along the A-P axis, while in Xenopus tissues they can be influenced by Fz-mediated PCP signaling. In these cases, as with the anisotropic apical constrictions of the mesoderm and amnioserosa, contractions lead to a permanent cell shape change, while in the follicle, although an anisotropic shape change occurs, it is transient. By illustrating distinct variations on a widespread theme, the follicle here again will extend our understanding of dynamic morphogenetic outcomes that shape tissues.

Concluding Remarks

The research reviewed here demonstrates how unappreciated morphogenetic mechanisms can contribute to the tremendous diversity of animal forms. Identification of phenomena such as tissue rotation, oscillating cellular contractions, and alternative planar polarity-generating pathways allows us to expand the morphogenetic toolkit; with further expansion, iterations and variations on these mechanisms, and their combinatorial usage with more familiar cell behaviors, we will eventually be able to account for the overall processes that shape tissues. The pursuit of this goal will push research towards the most exciting frontiers of development, such as the interfaces between familiar molecular signaling and mechanobiology. The Drosophila follicle, where traditional strengths of genetic manipulation can now be combined with live imaging and direct measurements of force, and whose relatively simple geometry lends itself well to mathematical modeling, is well-poised to be a major contributor. Finally, if well-studied systems can yield such surprises when examined with new tools and perspectives, we can only imagine what the study of currently unexamined tissues and organisms will bring.

Acknowledgements

We thank Nipam Patel, Mike Simon, Li He and Alex Paredez for helpful conversations and Lin Yuan for comments on the manuscript. We apologize to those authors whose work could only be cited in review. Morphogenesis work in the Bilder lab is supported by grants from the NIH and the Burroughs-Wellcome Trust; SLH has been supported by an American Heart Association Predoctoral Fellowship and a Berkeley Graduate Fellowship.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Adams DS, Keller R, Koehl MAR. The Mechanics of Notochord Elongation, Straightening and Stiffening in the Embryo of Xenopus-Laevis. Development. 1990;110:115–130. doi: 10.1242/dev.110.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aigouy B, Farhadifar R, Staple DB, Sagner A, Roper JC, Julicher F, Eaton S. Cell flow reorients the axis of planar polarity in the wing epithelium of Drosophila. Cell. 2010;142:773–786. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.07.042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelrod JD. Progress and challenges in understanding planar cell polarity signaling. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2009;20:964–971. doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baskin TI. Anisotropic expansion of the plant cell wall. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:203–222. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.20.082503.103053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bateman J, Reddy R, Saito H, Van Vactor D. The receptor tyrosine phosphatase Dlar and integrins organize actin filaments in the Drosophila follicular epithelium. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1317–1327. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00420-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becam I, Tanentzapf G, Lepesant J, Brown N, Huynh J. Integrin-independent repression of cadherin transcription by talin during axis formation in Drosophila. Nat Cell Biol. 2005;7:510–516. doi: 10.1038/ncb1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg CA. Tube formation in Drosophila egg chambers. Tissue Eng Part A. 2008;14:1479–1488. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertet C, Sulak L, Lecuit T. Myosin-dependent junction remodelling controls planar cell intercalation and axis elongation. Nature. 2004;429:667–671. doi: 10.1038/nature02590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caddy J, Wilanowski T, Darido C, Dworkin S, Ting SB, Zhao Q, Rank G, Auden A, Srivastava S, Papenfuss TA, et al. Epidermal wound repair is regulated by the planar cell polarity signaling pathway. Dev Cell. 2010;19:138–147. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavey M, Lecuit T. Molecular bases of cell-cell junctions stability and dynamics. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a002998. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a002998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciani L, Patel A, Allen ND, ffrench-Constant C. Mice lacking the giant protocadherin mFAT1 exhibit renal slit junction abnormalities and a partially penetrant cyclopia and anophthalmia phenotype. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23:3575–3582. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.10.3575-3582.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conder R, Yu H, Zahedi B, Harden N. The serine/threonine kinase dPak is required for polarized assembly of F-actin bundles and apical-basal polarity in the Drosophila follicular epithelium. Dev Biol. 2007;305:470–482. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2007.02.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwin C. On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection. Murray; London: 1859. [Google Scholar]

- David DJ, Tishkina A, Harris TJ. The PAR complex regulates pulsed actomyosin contractions during amnioserosa apical constriction in Drosophila. Development. 2010;137:1645–1655. doi: 10.1242/dev.044107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson LA, Keller R, DeSimone DW. Assembly and remodeling of the fibrillar fibronectin extracellular matrix during gastrulation and neurulation in Xenopus laevis. Dev Dyn. 2004;231:888–895. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delon I, Brown N. The integrin adhesion complex changes its composition and function during morphogenesis of an epithelium. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:4363–4374. doi: 10.1242/jcs.055996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng WM, Schneider M, Frock R, Castillejo-Lopez C, Gaman EA, Baumgartner S, Ruohola-Baker H. Dystroglycan is required for polarizing the epithelial cells and the oocyte in Drosophila. Development. 2003;130:173–184. doi: 10.1242/dev.00199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dominguez-Escobar J, Chastanet A, Crevenna AH, Fromion V, Wedlich-Soldner R, Carballido-Lopez R. Processive movement of MreB-associated cell wall biosynthetic complexes in bacteria. Science. 2011;333:225–228. doi: 10.1126/science.1203466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duffy J, Harrison D, Perrimon N. Identifying loci required for follicular patterning using directed mosaics. Development. 1998;125:2263–2271. doi: 10.1242/dev.125.12.2263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elul T, Keller R. Monopolar protrusive activity: A new morphogenic cell behavior in the neural plate dependent on vertical interactions with the mesoderm in Xenopus. Developmental Biology. 2000;224:3–19. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2000.9746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Gonzalez R, Zallen JA. Oscillatory behaviors and hierarchical assembly of contractile structures in intercalating cells. Phys Biol. 2011;8:045005. doi: 10.1088/1478-3975/8/4/045005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedl P, Gilmour D. Collective cell migration in morphogenesis, regeneration and cancer. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2009;10:445–457. doi: 10.1038/nrm2720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frydman H, Spradling A. The receptor-like tyrosine phosphatase lar is required for epithelial planar polarity and for axis determination within drosophila ovarian follicles. Development. 2001;128:3209–3220. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.16.3209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fux T, Went DF, Camenzind R. Movement Pattern and Ultrastructure of Rotating Follicles of the Pedogenetic Gall Midge, Heteropeza-Pygmaea Winnertz (Diptera-Cecidomyiidae) International Journal of Insect Morphology & Embryology. 1978;7:415–426. [Google Scholar]

- Garner EC, Bernard R, Wang W, Zhuang X, Rudner DZ, Mitchison T. Coupled, circumferential motions of the cell wall synthesis machinery and MreB filaments in B. subtilis. Science. 2011;333:222–225. doi: 10.1126/science.1203285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goodrich LV, Strutt D. Principles of planar polarity in animal development. Development. 2011;138:1877–1892. doi: 10.1242/dev.054080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorfinkiel N, Blanchard GB, Adams RJ, Martinez Arias A. Mechanical control of global cell behaviour during dorsal closure in Drosophila. Development. 2009;136:1889–1898. doi: 10.1242/dev.030866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goto T, Davidson L, Asashima M, Keller R. Planar cell polarity genes regulate polarized extracellular matrix deposition during frog gastrulation. Current Biology. 2005;15:787–793. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.03.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grammont M. Adherens junction remodeling by the Notch pathway in Drosophila melanogaster oogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2007;177:139–150. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200609079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo Q, Xia B, Moshiach S, Xu C, Jiang Y, Chen Y, Sun Y, Lahti JM, Zhang XA. The microenvironmental determinants for kidney epithelial cyst morphogenesis. Eur J Cell Biol. 2008;87:251–266. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutzeit H. The microfilament pattern in the somatic follicle cells of mid-vitellogenic ovarian follicles of Drosophila. Eur J Cell Biol. 1990;53:349–356. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutzeit H. Organization and in vitro activity of microfilament bundles associated with the basement membrane of Drosophila follicles. Acta Histochem Suppl. 1992;41:201–210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutzeit H, Eberhardt W, Gratwohl E. Laminin and basement membrane-associated microfilaments in wild-type and mutant Drosophila ovarian follicles. J Cell Sci. 1991;100:781–788. doi: 10.1242/jcs.100.4.781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haigo SL, Bilder D. Global tissue revolutions in a morphogenetic movement controlling elongation. Science. 2011;331:1071–1074. doi: 10.1126/science.1199424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Wang XB, Tang HL, Montell DJ. Tissue elongation requires oscillating contractions of a basal actomyosin network. Nature Cell Biology. 2010;12:1133–U1140. doi: 10.1038/ncb2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne-Badovinac S, Bilder D. Mass transit: epithelial morphogenesis in the Drosophila egg chamber. Dev Dyn. 2005;232:559–574. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou R, Liu L, Anees S, Hiroyasu S, Sibinga NE. The Fat1 cadherin integrates vascular smooth muscle cell growth and migration signals. J Cell Biol. 2006;173:417–429. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200508121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenny A. Planar cell polarity signaling in the Drosophila eye. Curr Top Dev Biol. 2010;93:189–227. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-385044-7.00007-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston RJ, Jr., Desplan C. Stochastic mechanisms of cell fate specification that yield random or robust outcomes. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:689–719. doi: 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100109-104113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keller R. Shaping the vertebrate body plan by polarized embryonic cell movements. Science. 2002;298:1950–1954. doi: 10.1126/science.1079478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HY, Davidson LA. Punctuated actin contractions during convergent extension and their permissive regulation by the non-canonical Wnt-signaling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2011;124:635–646. doi: 10.1242/jcs.067579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King R. Ovarian Development in Drosophila melanogaster. Academic Press; New York: 1970. [Google Scholar]

- King RC, Rubinson AC, Smith RF. Oogenesis in adult Drosophila melanogaster. Growth. 1956;20:121–157. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koehl MAR, Quillin KJ, Pell CA. Mechanical design of fiber-wound hydraulic skeletons: The stiffening and straightening of embryonic notochords. American Zoologist. 2000;40:28–41. [Google Scholar]

- Kolahi KS, White PF, Shreter DM, Classen AK, Bilder D, Mofrad MR. Quantitative analysis of epithelial morphogenesis in Drosophila oogenesis: New insights based on morphometric analysis and mechanical modeling. Dev Biol. 2009;331:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuroda R, Endo B, Abe M, Shimizu M. Chiral blastomere arrangement dictates zygotic left-right asymmetry pathway in snails. Nature. 2009;462:790–794. doi: 10.1038/nature08597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Cooley L. Jagunal is required for reorganizing the endoplasmic reticulum during Drosophila oogenesis. J Cell Biol. 2007;176:941–952. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200701048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahajan-Miklos S, Cooley L. Intercellular cytoplasm transport during Drosophila oogenesis. Dev Biol. 1994;165:336–351. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin AC, Kaschube M, Wieschaus EF. Pulsed contractions of an actin-myosin network drive apical constriction. Nature. 2009;457:495–499. doi: 10.1038/nature07522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matakatsu H, Blair SS. Interactions between Fat and Dachsous and the regulation of planar cell polarity in the Drosophila wing. Development. 2004;131:3785–3794. doi: 10.1242/dev.01254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirouse V, Christoforou C, Fritsch C, St Johnston D, Ray R. Dystroglycan and perlecan provide a basal cue required for epithelial polarity during energetic stress. Dev Cell. 2009;16:83–92. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2008.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- Moeller MJ, Soofi A, Braun GS, Li X, Watzl C, Kriz W, Holzman LB. Protocadherin FAT1 binds Ena/VASP proteins and is necessary for actin dynamics and cell polarization. EMBO J. 2004;23:3769–3779. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montell DJ. Border-cell migration: the race is on. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2003;4:13–24. doi: 10.1038/nrm1006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munro E, Nance J, Priess JR. Cortical flows powered by asymmetrical contraction transport PAR proteins to establish and maintain anterior-posterior polarity in the early C. elegans embryo. Dev Cell. 2004;7:413–424. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2004.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olguin P, Glavic A, Mlodzik M. Intertissue mechanical stress affects Frizzled-mediated planar cell polarity in the Drosophila notum epidermis. Curr Biol. 2011;21:236–242. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2011.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paredez A, Somerville C, Ehrhardt D. Visualization of cellulose synthase demonstrates functional association with microtubules. Science. 2006;312:1491–1495. doi: 10.1126/science.1126551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parsons JT, Horwitz AR, Schwartz MA. Cell adhesion: integrating cytoskeletal dynamics and cellular tension. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2010;11:633–643. doi: 10.1038/nrm2957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen OW, Ronnov-Jessen L, Howlett AR, Bissell MJ. Interaction with basement membrane serves to rapidly distinguish growth and differentiation pattern of normal and malignant human breast epithelial cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992;89:9064–9068. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.19.9064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl C, Bao Z. Chiral forces organize left-right patterning in C. elegans by uncoupling midline and anteroposterior axis. Dev Cell. 2010;19:402–412. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quintin S, Gally C, Labouesse M. Epithelial morphogenesis in embryos: asymmetries, motors and brakes. Trends Genet. 2008;24:221–230. doi: 10.1016/j.tig.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauzi M, Lenne PF, Lecuit T. Planar polarized actomyosin contractile flows control epithelial junction remodelling. Nature. 2010;468:1110–U1515. doi: 10.1038/nature09566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rorth P. Collective cell migration. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2009;25:407–429. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth S, Lynch JA. Symmetry Breaking During Drosophila Oogenesis. Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Biology. 2009;1 doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozario T, DeSimone DW. The extracellular matrix in development and morphogenesis: a dynamic view. Dev Biol. 2010;341:126–140. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.10.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer JK, Choi W, Jung KC, He L, Harris NJ, Peifer M. A contractile actomyosin network linked to adherens junctions by Canoe/afadin helps drive convergent extension. Mol Biol Cell. 2011;22:2491–2508. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer JM, Harrell JR, Shemer G, Sullivan-Brown J, Roh-Johnson M, Goldstein B. Apical constriction: a cell shape change that can drive morphogenesis. Dev Biol. 2010;341:5–19. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smart IH. In: Egg shape in birds. In Egg incubation: its effects on embryonic development in birds and reptiles. Deeming DC, Ferguson MWJ, editors. Cambridge University Press; Cambridge: 1991. pp. 101–116. [Google Scholar]

- Solon J, Kaya-Copur A, Colombelli J, Brunner D. Pulsed forces timed by a ratchet-like mechanism drive directed tissue movement during dorsal closure. Cell. 2009;137:1331–1342. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.03.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speder P, Adam G, Noselli S. Type ID unconventional myosin controls left-right asymmetry in Drosophila. Nature. 2006;440:803–807. doi: 10.1038/nature04623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spradling A. Developmental genetics of oogenesis. In: Bate M, Martinez-Arias A, editors. The development of Drosophila melanogaster. CSHL Press; New York: 1993. pp. 1–70. [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi K, Maeda R, Ando T, Okumura T, Nakazawa N, Hatori R, Nakamura M, Hozumi S, Fujiwara H, Matsuno K. Chirality in planar cell shape contributes to left-right asymmetric epithelial morphogenesis. Science. 2011;333:339–341. doi: 10.1126/science.1200940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner K, Mori H, Mroue R, Bruni-Cardoso A, Bissell MJ. Angular morphomechanics in the establishment of multicellular architecture of glandular tissues. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011 doi: 10.1073/pnas.1119578109. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanoue T, Takeichi M. Mammalian Fat1 cadherin regulates actin dynamics and cell-cell contact. J Cell Biol. 2004;165:517–528. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200403006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker JB, Meats M. Microtubules and control of insect egg shape. J Cell Biol. 1976;71:207–217. doi: 10.1083/jcb.71.1.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Teeffelen S, Wang S, Furchtgott L, Huang KC, Wingreen NS, Shaevitz JW, Gitai Z. The bacterial actin MreB rotates, and rotation depends on cell-wall assembly. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108:15822–15827. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1108999108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vichas A, Zallen JA. Translating cell polarity into tissue elongation. Semin Cell Dev Biol. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.semcdb.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viktorinova I, Konig T, Schlichting K, Dahmann C. The cadherin Fat2 is required for planar cell polarity in the Drosophila ovary. Development. 2009;136:4123–4132. doi: 10.1242/dev.039099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viktorinova I, Pismen LM, Aigouy B, Dahmann C. Modelling planar polarity of epithelia: the role of signal relay in collective cell polarization. J R Soc Interface. 2011 doi: 10.1098/rsif.2011.0117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallingford JB, Mitchell B. Strange as it may seem: the many links between Wnt signaling, planar cell polarity, and cilia. Genes Dev. 2011;25:201–213. doi: 10.1101/gad.2008011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver VM, Petersen OW, Wang F, Larabell CA, Briand P, Damsky C, Bissell MJ. Reversion of the malignant phenotype of human breast cells in three-dimensional culture and in vivo by integrin blocking antibodies. J Cell Biol. 1997;137:231–245. doi: 10.1083/jcb.137.1.231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Went D. Oocyte maturation without follicular epithelium alters egg shape in a Dipteran insect. J Exp Zool. 1978;205:149–155. [Google Scholar]

- Went DF, Junquera P. Embryonic development of insect eggs formed without follicular epithelium. Dev Biol. 1981;86:100–110. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90320-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wieschaus E, Audit C, Masson M. A Clonal Analysis of the Roles of Somatic-Cells and Germ Line during Oogenesis in Drosophila. Developmental Biology. 1981;88:92–103. doi: 10.1016/0012-1606(81)90221-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallen JA. Planar polarity and tissue morphogenesis. Cell. 2007;129:1051–1063. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zallen JA, Wieschaus E. Patterned gene expression directs bipolar planar polarity in Drosophila. Developmental Cell. 2004;6:343–355. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00060-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng D, Ferrari A, Ulmer J, Veligodskiy A, Fischer P, Spatz J, Ventikos Y, Poulikakos D, Kroschewski R. Three-dimensional modeling of mechanical forces in the extracellular matrix during epithelial lumen formation. Biophys J. 2006;90:4380–4391. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.073494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]