Abstract

A 71-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital with asthenia, weight loss, fever, cognitive impairment and shortness of breath. Physical examination showed hemiparesis and cerebellar ataxia. There was no superficial lymphadenopathy. Blood tests showed raised levels of C-reactive protein and lactate dehydrogenase. Bone marrow aspiration and biopsy were negative. [18F]fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/computed tomography (CT) showed intense uptake within a right apical nodule and intense and diffuse uptake of FDG in the lungs without corresponding structural CT abnormality. Lung biopsy showed intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL). FDG-PET findings in IVLBCL and causes of diffuse FDG lung uptake with and without CT abnormalities are discussed.

Keywords: Lymphoma, FDG-PET/CT, lung uptake

Introduction

Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma (IVLBCL) is a rare subtype of extranodal diffuse large B-cell lymphoma in which the lymphoma cells proliferate exclusively in the lumina of small vessels[1]. It was first described by Pfleger and Tappeiner in 1959[2]. It usually occurs in elderly patients, with a gender ratio close to 1 and a small preponderance in males. The most frequent presenting symptoms are fever and general fatigue, neurological symptoms and skin eruptions. Other common clinical findings at initial diagnosis are very heterogeneous and include gastrointestinal symptoms, dyspnea and oedema[1]. Subclinical respiratory involvement is found in 60% of patients at autopsy[3,4]. Lymphoma cells are usually not found in the lymph nodes and in the reticuloendothelial system[5]. Diagnosis is often delayed due to the non-specific symptoms and diagnosis of IVLCBL at autopsy is not uncommon. Therapy usually consists of chemotherapy and rituximab[1].

Case report

A 71-year-old woman was admitted to the internal medicine department of our hospital because of a 3-month history of deterioration of general condition. She had been hospitalized twice before in the previous 3 months before because of fever and raised inflammatory markers that persisted despite antibiotic therapy. A first thoraco-abdomino-pelvic computed tomography (CT) scan had not shown any abnormality and a second scan 2 months later demonstrated hepatosplenomegaly without lymphadenopathy. Brain CT scan with contrast showed focal enhancement in the right frontal lobe, the right occipital lobe and the cerebellum. Other investigations such as echocardiography, CT scan of the sinuses, colonoscopy, temporal artery biopsy and bone marrow aspiration did not show significant abnormalities. She was then admitted to our department for further investigation.

She presented with marked deterioration of general condition, asthenia, 5 kg weight loss, high-grade fever with shivering, shortness of breath and cognitive impairment. Physical examination showed hemiparesis and cerebellar ataxia of the right side. No superficial lymphadenopathy was found. Blood tests showed normocytic anaemia, normal white blood cell count and raised inflammatory markers.

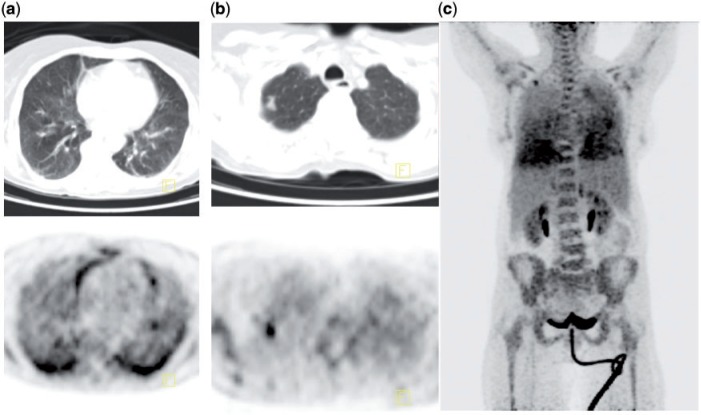

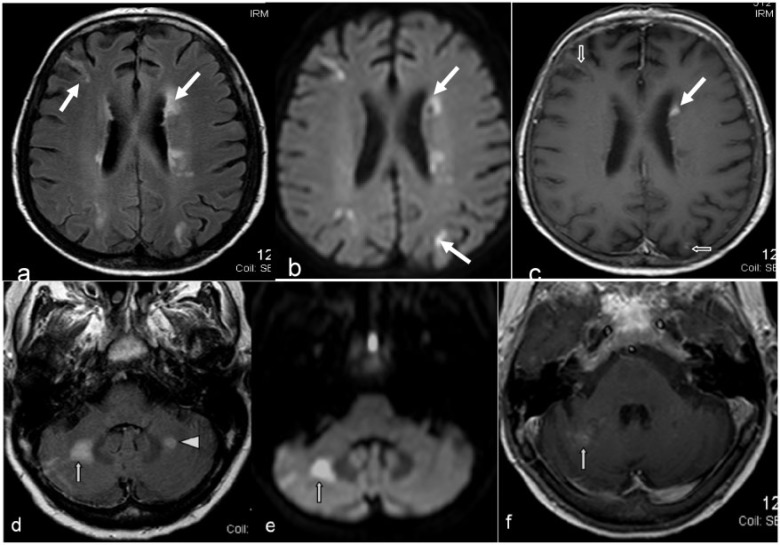

[18F]Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG)-positron emission tomography (PET)/CT scan showed bilateral high-grade diffuse homogeneous FDG uptake in the posterior and inferior aspect of the lungs, without corresponding CT abnormality (Fig. 1). There was also focal intense FDG uptake within a right apical nodule. Brain magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated disseminated ischemic lesions of different age.

Figure 1.

(a) Intense and diffuse lung uptake without CT structural abnormality on FDG-PET/CT. Accumulation of FDG within the lungs is homogeneous, with bilateral high-grade uptake in the posterior and inferior aspect of the lungs and diffuse low-grade uptake in the remainder of the lungs. (b) Intense and focal FDG uptake in a right apical nodule on a background of diffuse low-grade FDG uptake in normally aerated lungs. (c) maximum intensity projection (MIP) image demonstrating diffuse lung FDG uptake and focal uptake in a right apical lung nodule.

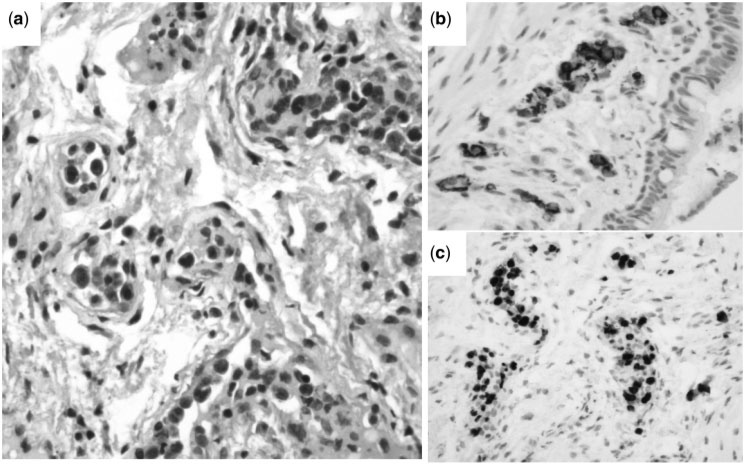

The FDG-PET/CT findings led to pulmonary endoscopy with biopsy. No macroscopic endobronchial abnormality was visualized. Pathologic examination of the biopsies showed large atypical lymphoid cells entirely located in the lumina of the septal capillary bed in the lung. These lymphoid cells had irregular nuclear contours, coarse chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and relatively abundant basophilic cytoplasm. The neoplastic cells in the lung were strongly and diffusely positive for CD20 and demonstrated a high proliferation index as revealed by MIB-1 (Ki-67). Diagnosis was IVLBCL.

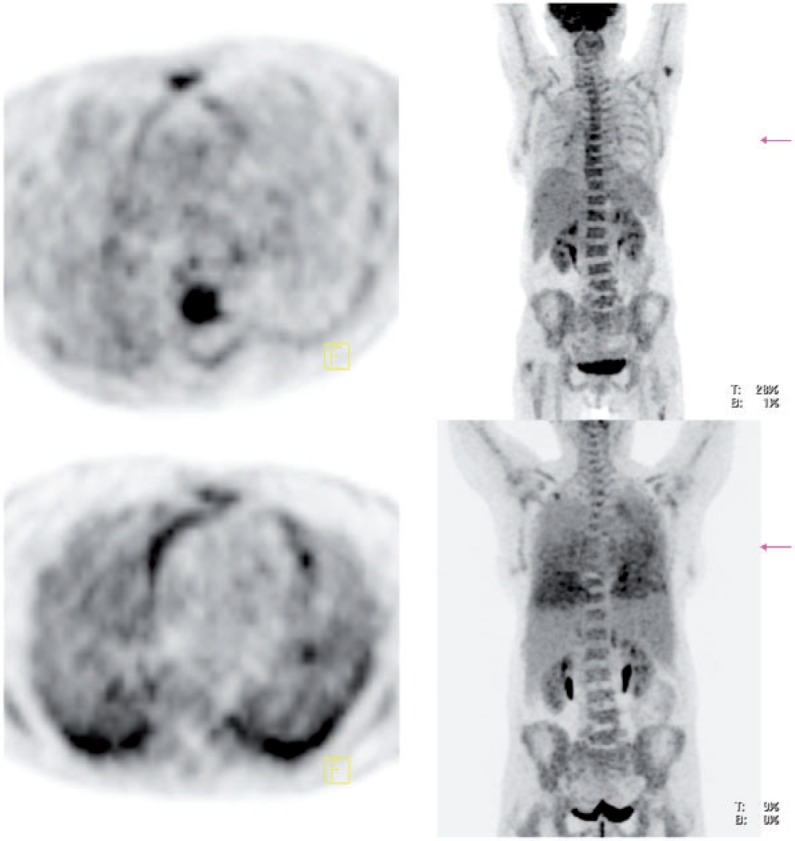

R-CHOP therapy was started and FDG-PET/CT evaluation after 2 cycles of chemotherapy showed resolution of the right apical nodule and marked decrease in lung uptake bilaterally with a persistent low-grade homogeneous uptake, consistent with partial metabolic response (Figs. 2–4). It was therefore assumed that IVLBCL involvement in the lung presented as diffuse lung uptake in areas without CT abnormality and as focal uptake in a nodule.

Figure 2.

FDG-PET/CT evaluation after 2 cycles of chemotherapy demonstrated a marked decrease in bilateral lung uptake with a persistent low-grade homogeneous uptake and resolution of the right apical nodule. Top row is a fused image transverse section of the lungs and MIP, status post-chemotherapy. Bottom row is a fused image transverse section of the lungs and MIP, status pre-chemotherapy.

Figure 3.

(a) The large atypical lymphoid cells are entirely located in the lumina of the septal capillary bed in the lung (hematoxylin–eosin, original magnification ×400). These lymphoid cells have irregular nuclear contours, coarse chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and relatively abundant basophilic cytoplasm. (b) Immunohistochemical features of the IVLBCL. The neoplastic cells in the lung are strongly and diffusely positive for CD20 (original magnifications ×200). (c) The neoplastic cells demonstrate a high proliferation index as revealed by MIB-1 (Ki-67) (original magnification ×200).

Figure 4.

Brain MRI with axial diffusion-weighted images (b, e), axial fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) weighted images (a, d), and axial contrast-enhanced T1-weighted images (c, f) showed subacute bilateral scattered brain infarcts affecting multiple vascular territories, carotid (a–c arrows) and vertebro-basilar (d–f), with cortical, subcortical and deep lesions (a, d arrows). Note the high signal of the left middle cerebellar peduncle without restriction of the apparent diffusion coefficient testifying to the different age of the ischemic lesions (d arrowhead, e). Strong scattered abnormal gyriform (c, empty arrows) and nodular (c, white arrow) enhancement is seen.

Discussion

This case report illustrates the added value of FDG-PET/CT in managing patients with general symptoms and no obvious diagnosis, leading here to the diagnosis of IVLCBL. In particular, the most striking aspect of the PET/CT scan in this patient was the intense and diffuse bilateral FDG lung uptake without pulmonary parenchymal abnormality on CT. This pattern has been described before in patients with IVLCBL. Miura et al.[6] described diffuse bilateral FDG uptake in the lungs, in the bilateral renal cortex and in the bones in 4 consecutive patients. No lung CT abnormality was reported in at least one of the patients but no information on the lung CT is provided for the 3 remaining patients. No follow-up imaging was mentioned. Kotake et al.[7] described bilateral and diffuse FDG accumulation in the lungs without CT abnormality and in the spleen in a patient with pulmonary hypertension. Follow-up with PET/CT showed resolution of the lung and spleen uptake after 2 cycles of chemotherapy. Kitanaka et al.[8] reported bilateral lung uptake on FDG-PET in a patient with fever and splenomegaly who had negative 67Ga scintigraphy and high-resolution chest CT scan. Follow-up PET showed resolution of the lung uptake after 6 cycles of chemotherapy. Our case report was different from the cases described above as it had an association of focal FDG accumulation within a lung nodule and diffuse accumulation in areas of normally ventilated lung on CT.

Various FDG-PET findings have been depicted in patients with IVLCBL (Table 1). Rare involved organs include the stomach[9], lymph node[10] and meninges[11]. Two published articles mention negative FDG-PET findings in IVLBCL[12,13]. Shimada et al.[1] found only 2 FDG-positive lesions out of 7 pathologically confirmed lesions.

Table 1.

Sites of IVLBCL involvement with positive FDG-PET findings in the literature

There have been a number of reports of diffuse lung uptake (Table 2). Yamane et al.[15] have described bilateral diffuse FDG lung uptake in a case of drug-induced pneumonitis in a patient treated with chemotherapy, where high-resolution CT (HRCT) performed on the same day did not show any abnormality. Three days later, a repeat HRCT showed disseminated patchy ground-glass opacities and interlobular septum thickening, in keeping with pneumonitis. Von Rohr et al.[16] reported a case of bleomycin-induced pneumonitis. FDG-PET showed unilateral diffuse FDG lung uptake corresponding with HRCT abnormality in keeping with bleomycin-induced pneumonitis. Rodrigues et al.[17] studied 8 patients at risk of acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) following blunt thoracic trauma and pulmonary contusion. All patients had FDG-PET 24–72 h after admission and did not meet the criteria for ARDS. Four patients went on to develop ARDS; 3 of these 4 patients had diffuse bilateral FDG lung uptake with increased FDG uptake in areas of normally aerated lung on CT scan. Yu et al.[18] reported a case of bilateral diffuse intense FDG uptake in posterior lower lungs in a patient with aspiration pneumonia. CT scan demonstrated a patchy area of consolidation in both posterior lower lungs. Prakash et al.[19] have described bilateral diffuse lung uptake in lymphangitic carcinomatosis. Groves et al.[20] have described diffuse bilateral lung FDG uptake in 2/36 patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and diffuse parenchymal lung disease. FDG uptake corresponded to abnormality on HRCT with the most intense areas of uptake corresponding most often to regions of honeycombing.

Table 2.

Reported causes of FDG-PET diffuse lung uptake

| Articles | Diffuse lung uptake | Cause | CT findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yamane et al.[15] | Bilateral | Chemotherapy-induced pneumonitis | Negative at first, positive 3 days later |

| Von Rohr et al.[16] | Unilateral | Bleomycin-induced pneumonitis | Positive |

| Yu et al.[18] | Bilateral | Aspiration pneumonia | Positive |

| Prakash et al.[19] | Bilateral | Lymphangitic carcinomatosis | Positive |

| Rodrigues et al.[17] | Bilateral | Acute respiratory distress syndrome | Negative then positive |

| Groves et al.[20] | Bilateral | Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and diffuse parenchymal lung disease | Positive |

From our search of the literature, it seems that bilateral diffuse FDG lung uptake with negative CT can be caused by chemotherapy-induced pneumonitis, ARDS or IVLBCL; and the only aetiology where CT remains negative after a few days is IVLBCL.

Conclusion

Diffuse bilateral FDG lung uptake with persistent normal lung CT scan must raise suspicion of IVLBCL. In the absence of other targets for tissue sampling, random lung biopsies may lead to a diagnosis.

Footnotes

This paper is available online at http://www.cancerimaging.org. In the event of a change in the URL address, please use the DOI provided to locate the paper.

References

- 1.Shimada K, Kinoshita T, Naoe T, Nakamura S. Presentation and management of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Lancet Oncol. 2009;10:895–902. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(09)70140-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pfleger L, Tappeiner J. [On the recognition of systematized endotheliomatosis of the cutaneous blood vessels (reticuloendotheliosis?] Hautarzt. 1959;10:359–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ko YH, Han JH, Go JH, et al. Intravascular lymphomatosis: a clinicopathological study of two cases presenting as an interstitial lung disease. Histopathology. 1997;31:555–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2559.1997.3310898.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pontier S, Selves J, Escamilla R, Hermant C, Krempf M. [Intra-vascular lymphoma presenting with respiratory symptoms] Rev Mal Respir. 2003;20:782–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Zuckerman D, Seliem R, Hochberg E. Intravascular lymphoma: the oncologist's “great imitator”. Oncologist. 2006;11:496–502. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.11-5-496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Miura Y, Tsudo M. Fluorodeoxyglucose-PET/CT for diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:56–7. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2009.0716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kotake T, Kosugi S, Takimoto T, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma presenting pulmonary arterial hypertension as an initial manifestation. Intern Med. 2010;49:51–4. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.49.2774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kitanaka A, Kubota Y, Imataki O, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma with FDG accumulation in the lung lacking CT/(67)gallium scintigraphy abnormality. Hematol Oncol. 2009;27:46–9. doi: 10.1002/hon.876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimada K, Kosugi H, Shimada S, et al. Evaluation of organ involvement in intravascular large B-cell lymphoma by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography. Int J Hematol. 2008;88:149–53. doi: 10.1007/s12185-008-0102-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sanli Y, Turkmen C, Saka B, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT in a case of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging. 2010;37:1801. doi: 10.1007/s00259-010-1516-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hofman MS, Fields P, Yung L, Mikhaeel NG, Ireland R, Nunan T. Meningeal recurrence of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma: early diagnosis with PET-CT. Br J Haematol. 2007;137:386. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06551.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kameoka Y, Takahashi N, Tagawa H, et al. A case of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma of the cutaneous variant: the first case in Asia. Int J Hematol. 2010;91:146–8. doi: 10.1007/s12185-009-0458-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kusaba T, Hatta T, Tanda S, et al. Histological analysis on adhesive molecules of renal intravascular large B cell lymphoma treated with CHOP chemotherapy and rituximab. Clin Nephrol. 2006;65:222–6. doi: 10.5414/cnp65222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martin-Duverneuil N, Mokhtari K, Behin A, Lafitte F, Hoang-Xuan K, Chiras J. Intravascular malignant lymphomatosis. Neuroradiology. 2002;44:749–54. doi: 10.1007/s00234-002-0808-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yamane T, Daimaru O, Ito S, et al. Drug-induced pneumonitis detected earlier by 18F-FDG-PET than by high-resolution CT: a case report with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. Ann Nucl Med. 2008;22:719–22. doi: 10.1007/s12149-008-0183-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.von Rohr L, Klaeser B, Joerger M, Kluckert T, Cerny T, Gillessen S. Increased pulmonary FDG uptake in bleomycin-associated pneumonitis. Onkologie. 2007;30:320–3. doi: 10.1159/000101517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rodrigues RS, Miller PR, Bozza FA, et al. FDG-PET in patients at risk for acute respiratory distress syndrome: a preliminary report. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:2273–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1220-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yu JQ, Kumar R, Xiu Y, Alavi A, Zhuang H. Diffuse FDG uptake in the lungs in aspiration pneumonia on positron emission tomographic imaging. Clin Nucl Med. 2004;29:567–8. doi: 10.1097/01.rlu.0000134986.58984.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Prakash P, Kalra MK, Sharma A, Shepard JA, Digumarthy SR. FDG PET/CT in assessment of pulmonary lymphangitic carcinomatosis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2010;194:231–6. doi: 10.2214/AJR.09.3059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Groves AM, Win T, Screaton NJ, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis and diffuse parenchymal lung disease: implications from initial experience with 18F-FDG PET/CT. J Nucl Med. 2009;50:538–45. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Takahashi T, Minato M, Tsukuda H, Yoshimoto M, Tsujisaki M. Successful treatment of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma diagnosed by bone marrow biopsy and FDG-PET scan. Intern Med. 2008;47:975–9. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.47.0808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Odawara J, Asada N, Aoki T, et al. 18F-Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography for evaluation of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma. Br J Haematol. 2007;136:684. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2006.06414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hoshino A, Kawada E, Ukita T, et al. Usefulness of FDG-PET to diagnose intravascular lymphomatosis presenting as fever of unknown origin. Am J Hematol. 2004;76:236–9. doi: 10.1002/ajh.20099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Balkema C, Meersseman W, Hermans G, et al. Usefulness of FDG-PET to diagnose intravascular lymphoma with encephalopathy and renal involvement. Acta Clin Belg. 2008;63:185–9. doi: 10.1179/acb.2008.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yago K, Yanagita S, Aono M, Matsuo K, Shimada H. [Usefulness of FDG-PET/CT for the diagnosis of intravascular large B-cell lymphoma presenting with fever of unknown origin and renal dysfunction] Rinsho Ketsueki. 2009;50:499–502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Boslooper K, Dijkhuizen D, van der Velden AW, Dal M, Meilof JF, Hoogenberg K. Intravascular lymphoma as an unusual cause of multifocal cerebral infarctions discovered on FDG-PET/CT. Neth J Med. 2010;68:261–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yamada S, Nishii R, Oka S, et al. FDG-PET a pivotal imaging modality for diagnosis of stroke-onset intravascular lymphoma. Arch Neurol. 2010;67:366–7. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lannoo L, Smets S, Steenkiste E, et al. Intravascular large B-cell lymphoma of the uterus presenting as fever of unknown origin (FUO) and revealed by FDG-PET. Acta Clin Belg. 2007;62:187–90. doi: 10.1179/acb.2007.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]