Abstract

Objectives To assess the incidence of and risks for congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, pericardial disease, and valvular abnormalities among adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers.

Design Retrospective cohort study.

Setting 26 institutions that participated in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study.

Participants 14 358 five year survivors of cancer diagnosed under the age of 21 with leukaemia, brain cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, kidney cancer, neuroblastoma, soft tissue sarcoma, or bone cancer between 1970 and 1986. Comparison group included 3899 siblings of cancer survivors.

Main outcome measures Participants or their parents (in participants aged less than 18 years) completed a questionnaire collecting information on demographic characteristics, height, weight, health habits, medical conditions, and surgical procedures occurring since diagnosis. The main outcome measures were the incidence of and risk factors for congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, pericardial disease, and valvular abnormalities in survivors of cancer compared with siblings.

Results Survivors of cancer were significantly more likely than siblings to report congestive heart failure (hazard ratio (HR) 5.9, 95% confidence interval 3.4 to 9.6; P<0.001), myocardial infarction (HR 5.0, 95% CI 2.3 to 10.4; P<0.001), pericardial disease (HR 6.3, 95% CI 3.3 to 11.9; P<0.001), or valvular abnormalities (HR 4.8, 95% CI 3.0 to 7.6; P<0.001). Exposure to 250 mg/m2 or more of anthracyclines increased the relative hazard of congestive heart failure, pericardial disease, and valvular abnormalities by two to five times compared with survivors who had not been exposed to anthracyclines. Cardiac radiation exposure of 1500 centigray or more increased the relative hazard of congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, pericardial disease, and valvular abnormalities by twofold to sixfold compared to non-irradiated survivors. The cumulative incidence of adverse cardiac outcomes in cancer survivors continued to increase up to 30 years after diagnosis.

Conclusion Survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer are at substantial risk for cardiovascular disease. Healthcare professionals must be aware of these risks when caring for this growing population.

Introduction

Therapeutic advances in paediatric oncology have led to an increase in the number of adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers, estimated at over 270 000 in the United States.1 However, survivors of childhood or adolescent cancer have significant long term morbidity related to their cancer therapy. Chronic adverse outcomes of cancer therapy include subsequent neoplasms,2 endocrine abnormalities,3 4 and growth and developmental delays.5

Cardiac toxicity can be a considerable complication both during and after cancer therapy, and contributes to significant morbidity and mortality in patients treated for cancer. Cardiovascular events are the leading non-malignant cause of death among survivors of childhood cancers, responsible for a sevenfold higher risk of death among such patients compared with age matched peers.6

Both chemotherapy and radiation therapy are known to be cardiotoxic.7 The cardiac effects of the anthracyclines are the most studied among antineoplastic agents; however, many other treatments—such as alkylating agents, vinca alkaloids, antimetabolites, and biological agents—are also recognised to have long term cardiac sequelae.8 Anthracyclines, such as doxorubicin or daunorubicin, are among the most commonly used and most effective chemotherapeutic agents, and have significantly contributed to cancer survival rates. This class of drugs has, however, been associated with dilated cardiomyopathy, an asymptomatic and progressive disorder that can develop in as many as 20% of cancer survivors 15-20 years after exposure.9 10 11 Radiation therapy can contribute to the development of heart failure, as well as induce pericardial injury, myocardial fibrosis, dysrhythmias, valvular abnormalities, and premature coronary artery disease.12

Few studies have investigated the risk factors for cardiac diseases in long term cancer survivors who are now adults.13 This study sought to assess the risk of cardiac late effects of cancer therapy occurring five or more years after cancer diagnosis. Using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort, we retrospectively assessed the incidence of and risk factors for congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, pericardial disease, and valvular abnormalities among adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers, relative to a sibling comparison group.

Methods

Study population and data collection

The Childhood Cancer Survivor Study is an ongoing, multi-institutional study of individuals who survived at least five years after treatment for childhood or adolescent cancer. The cohort includes individuals diagnosed before the age 21 years with leukaemia, brain cancer, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma, kidney cancer, neuroblastoma, soft tissue sarcoma, or bone cancer at one of 26 collaborating institutions between 1 January 1970 and 31 December 1986 (see web appendix).14 The initial survey of the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort was performed in 1995-6. A follow-up questionnaire was administered between 2000 and 2002 to confirm previously reported conditions and to add data on new first events (n=10 367 individuals participated).

At study enrolment, data were collected on demographic characteristics, current height and weight, and health habits, as well as medical conditions and surgical procedures occurring since diagnosis. A parent, spouse, or closest next of kin was contacted for those survivors known to have died more than five years after diagnosis. Study protocol and documents were reviewed and approved by the human subjects review committees at each participating institution. Cardiac complications were evaluated by a series of questions such as “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other healthcare professional that you have, or have had . . . congestive heart failure, a myocardial infarction, etc,” with self reported responses recorded as “yes,” “no,” or “not sure.” Study questionnaires are available at www.stjude.org/ccss. For affirmative answers, participants were asked to indicate the age at first occurrence.

We identified 20 627 eligible five year cancer survivors for participation, 3063 (14.8%) of whom could not be successfully located. Thus 17 564 were contacted, of whom14 358 (81.8%) completed a baseline questionnaire (fig 1 ). Other than vital status, no significant demographic differences were identified between participants and non-participants. A random sample of survivor participants was asked to nominate their nearest age sibling to participate in a control group; 3899 (81.5%) of the eligible siblings completed a questionnaire. Study methods and characteristics of participants and non-participants have been reported previously in detail.14 15

Fig 1 Flow chart of participation in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort. *Includes participants who also responded to the follow-up questionnaire (2000-2; n=10 367)

Survivors who reported a cardiac complication and were still alive or, when possible, proxy relatives for dead survivors, were contacted by telephone and asked a series of questions to document disease specifics. Participants were also asked to sign and return an authorisation form to allow medical record review. Records were requested from the physician(s) and hospitals listed for the cardiac care (not the participants’ paediatric oncologist) and returned to the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study coordinating centre. A standardised protocol was developed to validate each condition. The first 100 medical records obtained were reviewed independently by two physicians and subsequent records were reviewed by only one of the two physicians. Medical record validation of self reported cardiac events was attempted but determined to be unfeasible owing to inability to obtain and assure adequacy of records for all events and deaths (potentially from a cardiac event). We thus decided that it was not feasible to use validated cardiac outcomes in an unbiased fashion and, therefore, relied upon what a participant (or proxy) actually reported when completing the questionnaire.16 Only the first occurrence of each condition was reported, and only outcomes occurring five or more years after diagnosis for survivors and five or more years after birth for siblings were included in the analysis.

For all participants who returned a signed medical release, information concerning primary therapy was collected from medical records, including data on initial and relapse treatment and preparatory regimens for stem cell transplantation (if applicable). Qualitative information was abstracted from medical records for 42 specific chemotherapeutic drugs and quantitative information for 22 of these agents. Anthracycline dose (per m2) was determined by the sum of doxorubicin, daunorubicin, and three times the idarubicin dose.17

Mean radiation dose to the heart was estimated on the basis of detailed dosimetry calculations performed by physicists in the Department of Radiation Physics at MD Anderson Cancer Center, Houston, TX. The dosimetry method is described by Stovall and colleagues.18 The complete radiation therapy record for each patient was collected, including details of the treatment machine, radiation energy, tumour dose, and field locations. Treatment information was merged with measurements of scatter dose in tissue equivalent phantoms to estimate dose to the heart in centigray (cGy) for each individual, regardless of primary tumour site and target volume.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistics were calculated for demographic and treatment variables and, where appropriate, compared between cancer survivors and siblings. Such comparisons took into account intra-family correlation between a survivor and his or her sibling by using robust variance estimates from generalised estimating equations.19

Cox proportional hazard models with age as the time scale, as previously described by Yasui et al,20 were used to compare hazards of a cardiac event in survivors compared with siblings, with adjustments for gender, race, household income, education, and tobacco use. Potential within family correlation between a survivor and his or her sibling was accounted for by the use of sandwich variance estimates.21 Multiple imputation methodology for event-time relations was used when a cardiac event was reported but the participant did not report the age at which the event occurred.22 23 Age at first cardiac condition was imputed for 9% and 14% of survivors and siblings, respectively, who reported a specific condition (only age at diagnosis of valvular abnormalities was imputed for siblings).

An adjusted multivariable model that included risk factors such as gender, age at diagnosis, treatment era (in five year increments between 1970 and 1986), cardiac radiation dose, and anthracycline dose was constructed to evaluate the independent effects of each factor on each cardiac outcome among survivors. Other chemotherapy agents were included in the multivariable models if they had a P value of less than 0.2 in univariate analysis. Sensitivity analyses were carried out among patients for whom reported age at onset of cardiac condition was available. All qualitative conclusions, as well as nearly all quantitative results, were within tight agreement with the results of the multiple imputation analyses (data not shown). Two sided P values are reported and those of less than 0.05 were considered significant, although those between 0.01 and 0.05 should be interpreted as less conclusive owing to the large number of statistical comparisons carried out.

Results

Characteristics of cancer survivors and the sibling comparison group are shown in table 1. Among the 14 358 survivors of cancer, 7713 (53.7%) were male. Median age at diagnosis was 6.0 years (range 0-20 years), with 40% of participants under 5 years of age at diagnosis. Survivors were younger than siblings at the time of completing the most recent questionnaire (median 27.0 (8-51) years v 28.0 (3-56) years; P<0.001).

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study population

| Survivors (n=14 358) | Siblings (n=3899) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Gender | |||

| Female | 6645 (46.3) | 2024 (51.9) | 0.001 |

| Male | 7713 (53.7) | 1875 (48.1) | |

| Surveys completed | |||

| Initial survey (1994-5) | 14 358 (100) | 3899 (100) | — |

| Follow-up survey (2000-2) | 10367 (72) | 2540 (65) | |

| Age at most recent questionnaire* | |||

| <20 years | 2522 (17.6) | 686 (17.7) | <0.001 |

| 20-29 years | 6080 (42.3) | 1387 (35.6) | |

| 30-39 years | 4628 (32.2) | 1293 (33.2) | |

| 40-49 years | 1110 (7.7) | 489 (12.5) | |

| 50-59 years | 18 (0.1) | 41 (1.0) | |

| Time from cohort entry to most recent questionnaire† | |||

| 0-4 years | 991 (6.9) | 22 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| 5-14 years | 7268 (50.6) | 667 (17.1) | |

| 15-24 years | 5840 (40.7) | 1387 (35.6) | |

| 25-34 years | 259 (1.8) | 1293 (33.2) | |

| ≥35 years | 0 (0.0) | 530 (13.6) | |

*Survivors: median=27.0 (8-51) years; siblings: median=28.0 (3-56) years.

†Survivors: median=13.0 (0-27) years; siblings: median=23.0 (0-51) years.

More than half of all survivors received a combination of chemotherapy and radiation (table 2). Eleven percent received radiation and surgery alone and 18% received chemotherapy and surgery only, whereas a small proportion (0.3%) received only radiation therapy.

Table 2.

Characteristics of cancer survivors (n=14 358)

| n (%) | |

| Year of diagnosis | |

| 1970-4 | 2544 (17.7) |

| 1975-9 | 4069 (28.3) |

| 1980-6 | 7745 (53.9) |

| Age at diagnosis* | |

| 0-4 years | 5754 (40.1) |

| 5-9 years | 3200 (22.3) |

| 10-14 years | 2913 (20.3) |

| 15-20 years | 2491 (17.3) |

| Diagnosis | |

| Leukaemia | 4830 (33.6) |

| Brain cancer | 1876 (13.1) |

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1927 (13.4) |

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 1081 (7.5) |

| Kidney tumour | 1256 (8.7) |

| Neuroblastoma | 954 (6.6) |

| Soft tissue sarcoma | 1245 (8.7) |

| Bone cancer | 1189 (8.3) |

| Therapy† | |

| Surgery | 909 (7.3) |

| Radiation | 33 (0.3) |

| Chemotherapy | 816 (6.5) |

| Chemotherapy and radiation | 1459 (11.7) |

| Chemotherapy, radiation, and surgery | 5550 (44.3) |

| Radiation and surgery | 1479 (11.8) |

| Chemotherapy and surgery | 2274 (18.2) |

| Anthracycline dose† | |

| No anthracycline | 7385 (51.4) |

| <250 mg/m2 | 1931 (13.4) |

| ≥250 mg/m2 | 2834 (19.7) |

| Cardiac radiation dose† | |

| No cardiac radiation | 4160 (29) |

| <500 cGy | 4897 (34.1) |

| 500 to <1500 cGy | 832 (5.8) |

| 1500 to <3500 cGy | 1398 (9.7) |

| ≥3500 cGy | 988 (6.9) |

| Bleomycin† | |

| No | 11818 (82.3) |

| Yes | 756 (5.3) |

| Cisplatin† | |

| No | 11836 (82.4) |

| Yes | 738 (5.1) |

| Cyclophosphamide† | |

| No | 6880 (47.9) |

| Yes | 5694 (39.7) |

| Vincristine† | |

| No | 3543 (24.7) |

| Yes | 9031 (62.9) |

*Mean=6.0 years, range=0-20 years.

†All treatment data were missing for 1111 participants (308 refused and 803 had not yet signed medical release). In addition, 727 individuals were missing one or more data entry for surgery, chemotherapy, or radiation. Each treatment variable includes total counts, reflecting complete data available for that type of treatment.

The prevalence and rate of first occurrence of cardiac conditions are shown in table 3. Overall, the frequency of events among five year survivors of cancer was relatively low, yet excessive compared with the frequency in the sibling comparison group. Congestive heart failure had the highest prevalence in survivors (248 (1.7%) v 7 (0.2%) among siblings), followed by valvular abnormalities (238 (1.6%) v 21 (0.5%)) and pericardial disease (181 (1.3%) v 13 (0.3%)). Age adjusted rates per 10 000 person years for congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, pericardial disease, and valvular abnormalities among survivors were 9.7 (95% CI 9.4 to 10.1), 2.8 (2.4 to 3.3), 5.8 (5.4 to 6.4), and 6.4 (5.9 to 7.1), respectively. There were not sufficient events among siblings to accurately predict age dependent rates of cardiac disorders. Among survivors reporting a cardiac event, 146 (25%) reported more than one event. On the other hand, only four (10%) siblings reported more than one event. In survivors, the median age of onset of congestive heart failure was 25 years (range 7-50), myocardial infarction 30 years (range 11-44), pericardial disease 26 years (range 6-50), and valvular abnormalities 29 years (range 7-50). In the sibling group, median age of onset was 31 years (range 15-35), 31 years (range 18-40), 30 years (range 9-51), and 20 years (range 5-43) for congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, pericardial disease, and valvular abnormalities, respectively.

Table 3.

Prevalence and rates of reported first occurrence of a cardiac condition

| Survivors | Siblings | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence (n (%)) | Rate (95% CI) per 10 000 person years§ | Prevalence (n (%)) | ||

| Congestive heart failure* | 248 (1.7) | 9.7 (9.4 to 10.1) | 7 (0.2) | |

| Myocardial infarction | 101 (0.7) | 2.8 (2.4 to 3.3) | 6 (0.2) | |

| Pericardial disease† | 181 (1.3) | 5.8 (5.4 to 6.4) | 13 (0.3) | |

| Valvular abnormalities‡ | 238 (1.6) | 6.4 (5.9 to 7.1) | 21 (0.5) | |

*Congestive heart failure or cardiomyopathy.

†Pericarditis or pericardial constriction.

‡Stiff or leaking heart valves.

§Age adjusted and predicted at median survivors’ age of 20 years; too few events for stable age adjusted rate estimation among siblings.

The cumulative incidence of reported adverse cardiac events increased with time from diagnosis (fig 2 ). There was no plateau in this relation, with the possible exception of myocardial infarction. The incidence at 30 years after diagnosis was highest for congestive heart failure at 4.1% (95% CI 3.2 to 5.0%), followed by valvular abnormalities at 4.0% (95% CI 3.1 to 4.9%) and pericardial disease at 3.0% (95% CI 2.1 to 3.9%).

Fig 2 Cumulative incidence and 95% CI of cardiac disorders among childhood cancer survivors

After adjustment for demographic factors, education, household income, and smoking status, the risk of an adverse cardiac event among survivors of childhood cancer was fivefold to sixfold higher than that in the siblings (table 4). The highest relative hazard was for pericardial disease (hazard ratio (HR) 6.3, 95% CI 3.3 to 11.9). The relative hazard of congestive heart failure was six times that found among the siblings and the relative hazard of myocardial infarction was five times higher (HR 5.9, 95% CI 3.4 to 9.6 and HR 5.0, 95% CI 2.3 to 10.4, respectively).

Table 4.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals of reported cardiac conditions compared with sibling control group*

| Congestive heart failure | Myocardial infarction | Pericardial disease | Valvular abnormalities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| All diagnoses | 5.9 (3.4 to 9.6) | <0.001 | 5.0 (2.3 to 10.4) | <0.001 | 6.3 (3.3 to 11.9) | <0.001 | 4.8 (3.0 to 7.6) | <0.001 | |||

| Leukaemia | 4.2 (2.3 to 7.4) | <0.001 | 3.3 (1.2 to 8.6) | 0.018 | 2.6 (1.2 to 5.5) | 0.012 | 2.6 (1.3 to 4.9) | 0.004 | |||

| Brain tumour | 2.2 (1.0 to 4.7) | 0.039 | 6.1 (2.3 to 16.2) | <0.001 | 2.9 (1.2 to 6.8) | 0.014 | 2.2 (1.0 to 4.9) | 0.052† | |||

| Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 6.8 (3.9 to 11.7) | <0.001 | 12.2 (5.2 to 28.2) | <0.001 | 10.4 (5.4 to 19.9) | <0.001 | 10.5 (6.1 to 17.9) | <0.001 | |||

| Non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma | 5.1 (2.6 to 10.0) | <0.001 | 2.9 (0.9 to 9.6) | 0.085 | 4.7 (2.1 to 10.7) | <0.001 | 5.4 (2.7 to 10.8) | <0.001 | |||

| Kidney tumour | 4.9 (2.4 to 10.0) | <0.001 | ‡ | — | 2.4 (0.8 to 6.9) | 0.12† | 3.6 (1.6 to 8.4) | 0.003 | |||

| Neuroblastoma | 4.1 (1.7 to 9.7) | 0.002 | 11.1 (3.3 to 36.9) | <0.001 | 5.1 (1.9 to 14.0) | 0.002 | 7.7 (3.6 to 16.5) | <0.001 | |||

| Sarcoma | 4.6 (2.4 to 8.8) | <0.001 | 3.6 (1.2 to 11.0) | 0.026 | 5.1 (2.4 to 11.0) | <0.001 | 2.2 (1.0 to 4.9) | 0.050† | |||

| Bone cancer | 6.5 (3.6 to 12.0) | <0.001 | 4.2 (1.5 to 11.8) | 0.007 | 4.9 (2.3 to 10.5) | <0.001 | 4.4 (2.3 to 8.5) | <0.001 | |||

*Adjusted for gender, race, household income, education, and tobacco use.

†Not significant at P=0.05.

‡Unable to estimate.

Compared with the sibling cohort, the hazard for congestive heart failure was significantly elevated in survivors across all diagnoses, in particular Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HR 6.8, 95% CI 3.9 to 11.7) and bone cancer (HR 6.5, 95% CI 3.6 to 12.0; table 3) The relative hazard of myocardial infarction was highest among survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma (HR 12.2, 95% CI 5.2 to 28.2) and neuroblastoma (HR 11.1, 95% CI 3.3 to 36.9) and lowest among those who had leukaemia (HR 3.3, 95% CI 1.2 to 8.6). Survivors of leukaemia, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, neuroblastoma, and bone cancer had a significantly elevated hazard for each of the cardiac outcomes analysed.

An adjusted multivariable model was constructed to evaluate the independent effects on cardiac outcomes among survivors of the following risk factors: gender, age at diagnosis, treatment era, cardiac radiation exposure, anthracycline dose, and exposure to other chemotherapy agents (table 5).

Table 5.

Hazard ratios and 95% confidence intervals of reported cardiac conditions by treatment*

| Congestive heart failure | Myocardial infarction | Pericardial disease | Valvular abnormalities | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | Hazard ratio (95% CI) | P value | ||||

| Gender | |||||||||||

| Male | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | |||

| Female | 1.4 (1.1 to 1.9) | 0.018 | 0.6 (0.4 to 0.9) | 0.014 | 1.3 (0.9 to 1.8) | 0.15 | 1.6 (1.2 to 2.1) | 0.003 | |||

| Age at diagnosis | |||||||||||

| 0-4 years | 3.9 (2.1 to 7.3) | <0.001 | 1.0 (0.4 to 3.0) | 0.96 | 1.8 (0.9 to 3.8) | 0.13 | 2.7 (1.4 to 5.3) | 0.004 | |||

| 5-9 years | 2.3 (1.3 to 4.0) | 0.004 | 1.9 (0.9 to 4.0) | 0.090 | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.5) | 0.44 | 2.5 (1.5 to 4.3) | 0.001 | |||

| 10-14 years | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.9) | 0.37 | 0.8 (0.4 to 1.5) | 0.49 | 0.8 (0.5 to 1.3) | 0.41 | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.2) | 0.050 | |||

| 15-20 years | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | |||

| Treatment era | |||||||||||

| 1970-4 | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | |||

| 1975-9 | 1.1 (0.7 to 1.7) | 0.60 | 2.1 (1.2 to 3.8) | 0.010 | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.4) | 0.078** | 1.4 (1.0 to 2.0) | 0.090** | |||

| 1980-6 | 1.9 (1.2 to 3.0) | 0.008 | 2.2 (1.1 to 4.3) | 0.023 | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.4) | 0.25 | 1.8 (1.2 to 2.9) | 0.008 | |||

| Average cardiac radiation dose§ | |||||||||||

| No cardiac radiation | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | 1.0† | — | |||

| <500 cGy | 0.9 (0.6 to 1.4) | 0.75 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.4) | 0.36 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1) | 0.11 | 0.6 (0.4 to 1.0) | 0.063 | |||

| 500 to <1500 cGy | 1.3 (0.7 to 2.5) | 0.43 | 0.6 (0.1 to 2.5) | 0.45 | 1.9 (0.9 to 3.9) | 0.077 | 1.4 (0.7 to 2.9) | 0.40 | |||

| 1500 to <3500 cGy | 2.2 (1.4 to 3.5) | <0.001 | 2.4 (1.2 to 4.9) | 0.011 | 2.2 (1.3 to 3.9) | 0.005 | 3.3 (2.1 to 5.1) | <0.001 | |||

| ≥3500 cGy | 4.5 (2.8 to 7.2) | <0.001 | 3.6 (1.9 to 6.9) | <0.001 | 4.8 (2.8 to 8.3) | <0.001 | 5.5 (3.5 to 8.6) | <0.001 | |||

| Chemotherapy | |||||||||||

| Anthracycline v none¶ | |||||||||||

| <250 mg/m2 | 2.4 (1.5 to 3.9) | <0.001 | 1.3 (0.6 to 2.8) | 0.50 | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.9) | 0.13 | 1.4 (0.8 to 2.3) | 0.25 | |||

| ≥250 mg/m2 | 5.2 (3.6 to 7.4) | <0.001 | 1.1 (0.5 to 2.1) | 0.87 | 1.8 (1.1 to 3.0) | 0.020 | 2.3 (1.6 to 3.3) | <0.001 | |||

| Cisplatin v none | 1.7 (0.9 to 2.9) | 0.062 | ‡ | — | ‡ | — | ‡ | — | |||

| Vincristine v none | ‡ | — | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.1) | 0.081 | ‡ | — | ‡ | — | |||

| Bleomycin v none | ‡ | — | ‡ | — | 1.6 (0.9 to 2.9) | 0.091 | ‡ | — | |||

| Cyclophosphamide v none | ‡ | — | ‡ | — | 1.5 (1.0 to 2.3) | 0.049** | ‡ | — | |||

*Estimates adjusted for all variables in the table as well as race, household income, education, and tobacco use.

†Reference group.

‡Not included in model.

§Test for trend (P value)-all outcomes (<0.001).

¶Test for trend (P value)-congestive heart failure (<0.001), myocardial infarction (0.8), pericardial disease (0.03), valvular disease (<0.001).

**Not significant at P=0.05.

Significant risk factors for congestive heart failure included female gender, age less than 10 years at diagnosis, treatment during the 1980s, increasing anthracycline exposure, and radiation exposure above 1500 cGy. An association with exposure to cisplatin was suggested, but this relation did not reach statistical significance (P=0.06). For myocardial infarction, female gender was protective, and age at diagnosis and anthracycline dose were not significantly associated with an increased risk. However, radiation doses of 3500 cGy or more were significantly associated with myocardial infarction (P for trend <0.001). Pericardial disease was not associated with gender or age at diagnosis, but was significantly associated with increasing doses of cardiac radiation, exposure to an anthracycline dose of 250 mg/m2 or more, and exposure to any dose of cyclophosphamide. An association with bleomycin was suggested but was not statistically significant (P=0.09). Females were more likely than males to report valvular dysfunction, which was associated with age at diagnosis of 14 years or less, treatment in the 1980s, higher doses of radiation therapy, and exposure to an anthracycline dose of 250 mg/m2 or more (table 4).

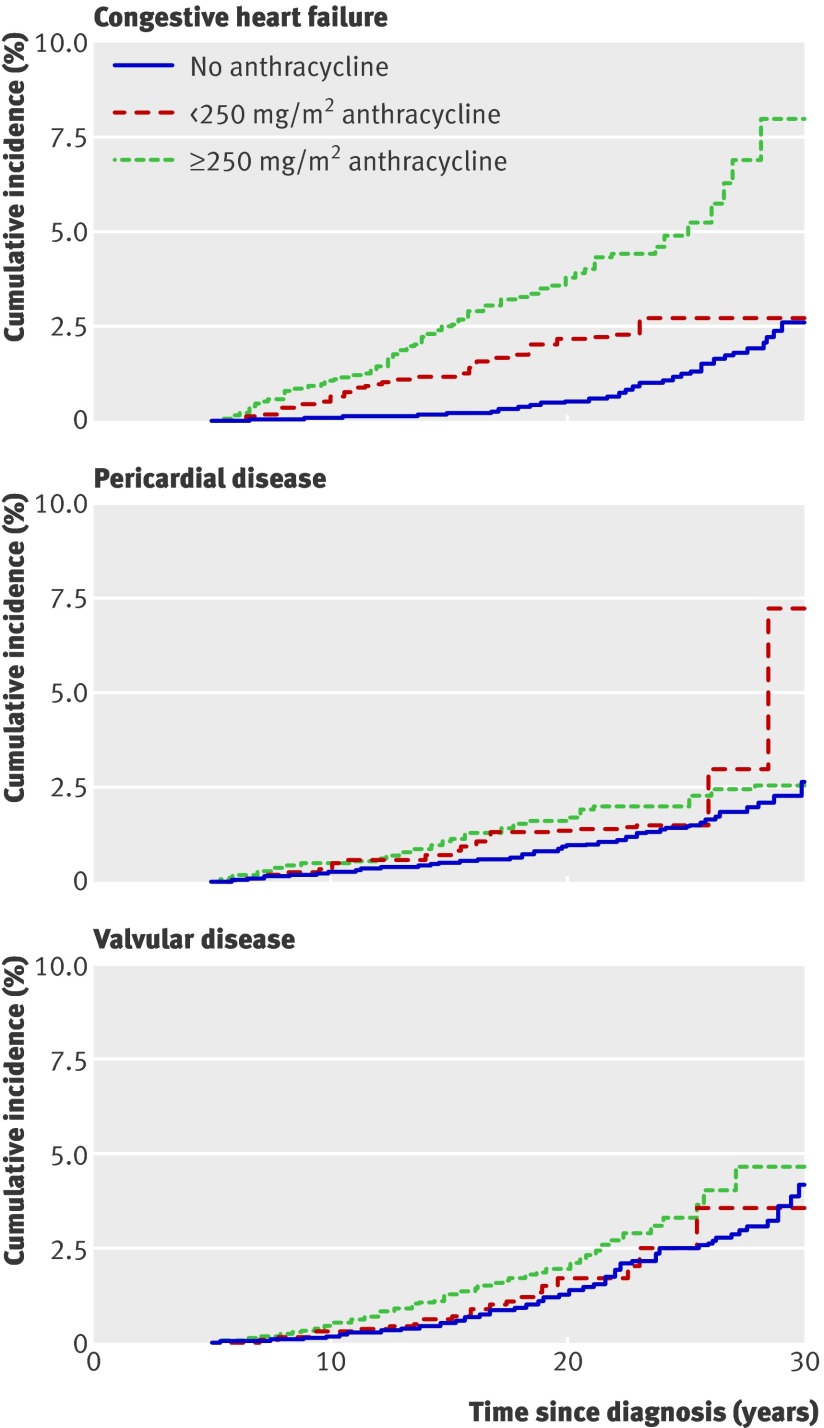

Cumulative incidence curves illustrate the dose- response relationship between anthracycline exposure and congestive heart failure, pericardial disease, and valvular abnormalities (fig 3 ) and that of increasing radiation doses with congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, pericardial disease, and valvular abnormalities (fig 4 ).

Fig 3 Cumulative incidence of cardiac disorders among childhood cancer survivors by anthracycline dose

Fig 4 Cumulative incidence of cardiac disorders among childhood cancer survivors by average cardiac radiation dose

Discussion

Principal findings of the study

Cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death in the developed world,24 contributes to early morbidity and mortality among cancer survivors. Using data from the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study cohort, we performed the largest analysis to date of cardiovascular disease among adult survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers. We found significantly increased risks for congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, pericardial disease, and valvular dysfunction among adult cancer survivors compared with a sibling control group. Previous research has shown the excess cardiovascular mortality in this cohort6; this study illustrates the risk of reported cardiovascular disease rather than mortality.

Cardiac events, generally rare in young adults, were significantly more frequent in young survivors of cancer than in siblings. At a mean age of 27 years, 248 survivors reported congestive heart failure and 101 had experienced a myocardial infarction. The incidence of each cardiovascular outcome increased with time from diagnosis, which suggests that the long term impact of treatment on the health of cancer survivors will be substantial. The relative hazard of a survivor reporting cardiovascular disease was higher than that in the sibling group across most diagnoses and was significantly associated with specific therapeutic exposures, notably exposure to anthracyclines or a cardiac radiation dose of more than 1500 cGy.

Comparison with other studies

Most studies of cardiovascular outcomes among survivors of childhood cancer have concentrated on a limited number of diagnoses (that is, leukaemia, Hodgkin’s lymphoma, Wilms’s tumour, and bone tumour)25 26 27 28 or a particular dose of radiation.29 30 Only a few single institution studies have included a range of diagnoses similar to ours and fewer have included such a broad range of cardiovascular outcomes.31 32 33 34

Congestive heart failure

In our study, the relative hazard of congestive heart failure was increased for all diagnostic groups compared with the sibling control group. Among survivors, the risk was associated with female gender, age less than 10 years at diagnosis, treatment during the 1980s, and higher radiation therapy and anthracycline doses. Of note, the relative hazard of congestive heart failure was 40% higher in female survivors than in male survivors. This finding is consistent with other reports, although the reason for this gender difference is unclear.

These findings are similar to those in previous reports. Anthracycline induced cardiomyopathy has been noted following treatment for a variety of malignancies and can occur after any dose.11 35 Steinherz and colleagues reported that 23% of long term survivors of paediatric malignancies who had received chemotherapy had cardiovascular disease 20 years later; a total of 11% had congestive heart failure following anthracycline doses of less than 400 mg/m2 and 100% had the heart disorder at doses of more than 800 mg/m2.9 In addition, the risk increases with time and higher cumulative exposures. For example, in a study of over 600 childhood cancer survivors, Kremer and colleagues found an elevated risk of anthracycline induced heart failure among those who had received a cumulative dose of more than 300 mg/m2, which increased over 15 years.31 In our cohort, the relative hazard of congestive heart failure associated with anthracycline treatment was 2.4-fold higher at doses of less than 250 mg/m2 and 5.2-fold higher at doses of 250 mg/m2 or more, compared with individuals who had not been exposed to anthracyclines.

We also found a potential association between congestive heart failure and cisplatin exposure. This relation has been reported previously and is thought to be related to multiagent chemotherapy.36

The 30 year cumulative incidence of congestive heart failure in the entire cohort was 4.1% (95% CI 3.2 to 5.0). This is lower than in other reports but includes all diagnostic groups in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study and all anthracycline and radiation therapy dose levels. Notably, the congestive heart failure incidence curve does not seem to plateau and accelerates markedly as childhood cancer survivors enter adulthood.

Therapy induced cardiomyopathy can be asymptomatic in over 50% of cancer survivors,10 yet is detectable with non-invasive cardiac testing.37 Cardiac failure may become apparent only with a physiologic stress such as infection or pregnancy.38 39 Subclinical disease could not be assessed in this analysis, thus the true frequency and risk of cardiac dysfunction may actually be higher. Optimal therapy for chemotherapy induced congestive heart failure has been extrapolated from therapies used for cardiac disease caused by other factors and, thus far, has shown only limited benefit.40 The development of new cardioprotective agents and preventive measures may help ameliorate this risk in the future.41

Myocardial infarction

Ischaemic heart disease after childhood cancer therapy has been less extensively studied; however, to some extent previous studies and our study have suggested that the risk of ischaemic heart disease may become more apparent with longer follow-up. Most studies of myocardial infarction among cancer survivors have focused on survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma, and other studies frequently combine paediatric and adult patients. Hancock and colleagues specifically evaluated survivors of childhood and adolescent Hodgkin’s lymphoma and reported a 30-fold increase in the risk of cardiac death and 41-fold increase in death related to myocardial infarction in this cohort compared with the age matched general population.42 Deaths occurred 3-22 years from commencement of therapy among those patients treated with more than 4200 cGy mediastinal radiation. Reinders et al. reported 31 (12%) ischaemic events and 12 (4.7%) deaths among 258 survivors of paediatric or adult Hodgkin’s lymphoma; these events occurred a median of 11.8 years after treatment and with a mean radiation therapy dose of 3660 cGy.43 Male gender, increasing age, and pretreatment cardiac history were significant predictors of ischaemic heart disease in this study. The relative risk of hospital admission for myocardial infarction was 2.7 (95% CI 1.7 to 4.0) and the standardised mortality ratio was 5.3 (95% CI 2.7 to 9.3). King and colleagues did not identify a significantly elevated relative risk of morbid cardiac events among 326 patients with Hodgkin’s lymphoma treated with radiation therapy (mean mantle radiation dose 4430 cGy) but reported 14 (4.3%) myocardial infarctions, seven (2.1%) of which were fatal.44 The risk tended to be higher for patients treated when they were under 21 years of age.

Our study evaluated the relative hazard of first myocardial infarction, rather than death, in five year survivors of childhood and adolescent cancer, and generally found the risks comparable with those reported by others. The highest risks were among survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma or neuroblastoma, and the risk was negligible among survivors of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma. However, a risk of myocardial infarction was noted with much lower doses of radiation therapy than those covered in other reports. Our study included a variety of diagnoses instead of just Hodgkin’s lymphoma, assessed survivors five years after diagnosis or later, and had a longer follow-up (mean 20 years) than most other studies. The long follow-up time in our study may account for the observed increased risk of myocardial infarction in cancer survivors heavily exposed to a variety of cardiotoxic agents such as anthracyclines, cisplatin, and radiation therapy. Only the study by Aleman et al. had a similar length follow-up (18 years); this group reported a 3.6-fold higher risk of myocardial infarction among five year survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma compared with the general population.45 Hancock and colleagues’ study suggested an early latency for fatal ischaemic disease after high dose radiation therapy (4000-4500 cGy) in survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma.42 Our data suggest that even low doses of radiation therapy (1500-3500 cGy) can cause damage to the coronary circulation, which may only become apparent with prolonged follow-up. Although platinum containing regimens have also been associated with ischaemic disease among survivors of testicular cancer,46 we did not identify an association between myocardial infarction and cisplatin.

Survivors of neuroblastoma in our study had a notable 11-fold increased relative hazard of myocardial infarction. Most reports of late complications in survivors of neuroblastoma have concentrated on neurosensory, endocrine, and musculoskeletal abnormalities. Few studies have reported cardiovascular abnormalities in this population, other than a study at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center that identified five survivors of advanced stage neuroblastoma with cardiac disease among a cohort of 63 patients.47

Pericardial disease

Our study demonstrates a threefold to 10-fold higher relative hazard of pericardial disease in cancer survivors compared with sibling controls across all types of cancers examined, with the exception of kidney cancer. Additionally, the 30 year incidence of pericardial disease for survivors in all diagnostic groups was 3.0% (95% CI 2.1 to 3.9).

Acute pericardial injury following cancer therapy has been reported previously; however, studies examining pericardial abnormalities among cancer survivors five or more years after diagnosis are uncommon. Many of the published studies focus on patients with adult Hodgkin’s lymphoma and assess radiation related pericardial disease or subacute injury occurring within a few years of therapy.48 49 50 One study in survivors of childhood or adolescent Hodgkin’s lymphoma found a 4% risk for pericardiectomy 17 years after therapy.42

Valvular abnormalities

Our analysis included many different cancer diagnoses and found a nearly fivefold higher relative hazard of valvular abnormalities in survivors of cancer than in the sibling control group, as well as an association between valvular disease and higher doses of anthracyclines.

Again, most previous studies have focused on survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma who were diagnosed as adults. Valvular dysfunction may be a fairly common late complication of radiation therapy to the chest.51 One study showed that 6.2% of survivors of Hodgkin’s lymphoma developed clinically significant valvular abnormalities at a median of 22 years after diagnosis.12 A screening study in asymptomatic cancer survivors who had received at least 3500 cGy of mantle radiation suggested that up to 60% would present with some type of valvular disease.52 Another study of Hodgkin’s lymphoma survivors younger than 41 years of age at treatment found a sevenfold increased risk of valvular abnormalities associated with mantle radiation and a twofold increased risk associated with anthracycline therapy.45

Strengths and limitations of the study

Some aspects of this research need to be considered when interpreting the findings of our study. The large survivor population in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study, which is well characterised with regard to cancer and treatment exposures, provides an excellent resource for studying clinically diagnosed outcomes. The large size and broad geographic distribution of the cohort does, however, necessitate reliance on self reported outcomes and makes validation of negative responses impractical.

We attempted to validate all positively reported outcomes by either telephone contact or medical record review, but determined that it was not feasible to obtain the appropriate documentation from a sufficiently high proportion of the cases. The key difficulty was that validation was only possible in a relatively small subset of the population who actually reported an event. For example, in a sample of 292 survivors reporting congestive heart failure at any time after diagnosis, only 189 (65%) could be contacted for a telephone interview. We could obtain relevant cardiac medical records for only 103 of these participants (35% of 292; 54% of 189), and 25 (24%) of these records did not contain adequate information to determine cardiac disease status. Furthermore, 64% of those participants we could not validate by telephone interview had died compared with 14% of those validated by telephone interview (via proxy). In addition, it is likely that a relatively high proportion of individuals who self reported a cardiac event on the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study surveys and subsequently died would have had a confirmed cardiac event had they lived long enough, owing to the high mortality rate from these conditions. Relying on death certificates for confirmation of cause of death adds additional variability. Epidemiologic studies have shown death certificate data to have limited reliability and accuracy.53 54 Thus, the accuracy of self reported cardiac outcomes reflects an area of potential concern. On the other hand, the validity of self reported long term events among cancer survivors has been found to be generally high, with 83% sensitivity and 98% specificity for myocardial infarction.55

Another issue of concern is the potential for surveillance bias, given that a proportion of the study population had been exposed to known cardiotoxic substances and thus may have been under greater medical monitoring. Such bias would overestimate the risk of adverse cardiac outcomes. Previous reports, however, have found a poor knowledge of and little appropriate screening for late effects of treatment among survivors of childhood cancer.56 57

Other than gender and smoking status, details on traditional Framingham risk factors were not available for our cohort. Framingham risk factors were identified in a population older than ours and are thought to take years to affect cardiovascular health. Hypertension and dyslipidaemia may have developed over time in our population, but the participants’ blood pressure and lipid status at entry to the cohort is unknown. Surveillance for Framingham risk factors may be of increased importance in a population exposed to chemotherapy or radiation therapy early in life because of the additional risks these chemotherapy/radiation therapy exposed patients have as they become adults and enter an age group where Framingham risk factors apply and cardiovascular disease is more prevalent.

Another potential limitation to be considered is the fact that the proportion of deaths among eligible individuals who were lost to follow-up or refused to participate is higher than that in those who were study participants (18% v 12%). This finding raises the possibility that more of the non-participating individuals than the participating individuals had a fatal cardiac condition, which could mean that our study underestimates the true incidence of cardiac conditions in this population. However, the proportion of individuals with death attributed to a cardiac cause on death certificate did not differ between participants and non-participants (0.8% v 0.6%, respectively), providing some reassurance that this may not be the case.

Conclusions and further research

We found a significant incidence of cardiovascular complications among adult survivors of a variety of childhood and adolescent cancers years after treatment. This research confirms in the largest cohort of childhood and adolescent cancer survivors in the world previous reports of adverse cardiac outcomes after cancer treatment and identifies several new risk factors. Young adults who survive childhood or adolescent cancer are clearly at risk for early cardiac morbidity and mortality not typically recognised within this age group. Such individuals require ongoing clinical monitoring, particularly as they approach ages in which cardiovascular disease becomes more prevalent. Further research is needed to determine the proper risk stratification for these survivors and the costs and benefits of early cardiovascular screening.

What is already known on this topic

Survivors of childhood cancer have significant long term morbidity related to their cancer therapy

Cardiovascular events are the leading non-malignant cause of death among survivors of childhood and adolescent cancers

What this study adds

Young adult survivors of childhood cancer are at risk for a variety of adverse cardiovascular outcomes—such as congestive heart failure, myocardial infarction, pericardial disease, and valvular abnormalities—as late as 30 years after therapy

This risk is apparent at lower exposures to anthracyclines and radiation therapy than previously recognised

Contributors: LLR, CAS, and ACM were responsible for the conception and design of the study. DAM, MWY, ACM, PM, MS, SSD, TK, and WML undertook the analysis and interpretation of the data. DAM, MWY, TK, WML, and LLR drafted the manuscript and completed critical revisions. Final approval of manuscript lay with all authors. DAM acts as guarantor.

Funding: LLR, principal investigator, and WML were supported by grant U24 CA 55727 from the National Cancer Institute, Bethesda, MD, and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities, Memphis, TN. USA. DAM was supported by grant 1K12RR023247 from the National Institute of Health, Bethesda, MD, and the Children’s Cancer Research Fund, Minneapolis, MN, USA. The funding agencies were not involved in data collection, analysis, interpretation, or writing of this manuscript.

Competing interests: None declared.

Ethical approval: Study protocol and documents were reviewed and approved by the Human Subjects Review Committees at each participating institution.

Data sharing: No additional data available.

Cite this as: BMJ 2009;339:b4606

Web Extra. Extra material supplied by the author

Other investigators and institutions participating in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study

References

- 1.Hewitt M WS, Simone JV. Childhood cancer survivorship improving care and quality of life. The National Academies Press, 2003. [PubMed]

- 2.Neglia JP, Friedman DL, Yasui Y, Mertens AC, Hammond S, Stovall M, et al. Second malignant neoplasms in five-year survivors of childhood cancer: childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2001;93:618-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gurney JG, Kadan-Lottick NS, Packer RJ, Neglia JP, Sklar CA, Punyko JA, et al. Endocrine and cardiovascular late effects among adult survivors of childhood brain tumors: childhood cancer survivor study. Cancer 2003;97:663-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sklar C, Whitton J, Mertens A, Stovall M, Green D, Marina N, et al. Abnormalities of the thyroid in survivors of Hodgkin’s disease: data from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2000;85:3227-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gurney JG, Ness KK, Stovall M, Wolden S, Punyko JA, Neglia JP, et al. Final height and body mass index among adult survivors of childhood brain cancer: childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:4731-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mertens AC, Liu Q, Neglia JP, Wasilewski K, Leisenring W, Armstrong GT, et al. Cause-specific late mortality among 5-year survivors of childhood cancer: the childhood cancer survivor study. J Natl Cancer Inst 2008;100:1368-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Adams MJ, Lipshultz SE. Pathophysiology of anthracycline- and radiation-associated cardiomyopathies: implications for screening and prevention. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2005;44:600-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Floyd JD, Nguyen DT, Lobins RL, Bashir Q, Doll DC, Perry MC. Cardiotoxicity of cancer therapy. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:7685-96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinherz LJ, Steinherz PG, Tan CT, Heller G, Murphy ML. Cardiac toxicity 4 to 20 years after completing anthracycline therapy. JAMA 1991;266:1672-7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kremer LC, van der Pal HJ, Offringa M, van Dalen EC, Voute PA. Frequency and risk factors of subclinical cardiotoxicity after anthracycline therapy in children: a systematic review. Ann Oncol 2002;13:819-29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lipshultz SE, Lipsitz SR, Sallan SE, Dalton VM, Mone SM, Gelber RD, et al. Chronic progressive cardiac dysfunction years after doxorubicin therapy for childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. J Clin Oncol 2005;23:2629-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hull MC, Morris CG, Pepine CJ, Mendenhall NP. Valvular dysfunction and carotid, subclavian, and coronary artery disease in survivors of hodgkin lymphoma treated with radiation therapy. JAMA 2003;290:2831-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mulrooney DA, Neglia JP, Hudson MM. Caring for adult survivors of childhood cancer. Curr Treat Options Oncol 2008;9:51-66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robison LL, Mertens AC, Boice JD, Breslow NE, Donaldson SS, Green DM, et al. Study design and cohort characteristics of the childhood cancer survivor study: a multi-institutional collaborative project. Med Pediatr Oncol 2002;38:229-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mertens AC, Walls RS, Taylor L, Mitby PA, Whitton J, Inskip PD, et al. Characteristics of childhood cancer survivors predicted their successful tracing. J Clin Epidemiol 2004;57:933-44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leisenring WM, Mertens AC, Armstrong GT, Stovall MA, Neglia JP, Lanctot JQ, et al. Pediatric cancer survivorship research: experience of the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 2009;27:2319-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pai VB, Nahata MC. Cardiotoxicity of chemotherapeutic agents: incidence, treatment and prevention. Drug Saf 2000;22:263-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stovall M, Weathers R, Kasper C, Smith SA, Travis L, Ron E, et al. Dose reconstruction for therapeutic and diagnostic radiation exposures: use in epidemiological studies. Radiat Res 2006;166:141-57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liang K-Y ZS. Longitudinal data analysis using generalized linear models. Biometrika 1986;73:13-22. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yasui Y, Liu Y, Neglia JP, Friedman DL, Bhatia S, Meadows AT, et al. A methodological issue in the analysis of second-primary cancer incidence in long-term survivors of childhood cancers. Am J Epidemiol 2003;158:1108-13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Therneau TM, Grambsch PM. Modeling survival data extending the Cox model. Springer-Verlag, 2000.

- 22.Taylor JM, Munoz A, Bass SM, Saah AJ, Chmiel JS, Kingsley LA. Estimating the distribution of times from HIV seroconversion to AIDS using multiple imputation. Multicentre AIDS Cohort Study. Stat Med 1990;9:505-14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rubin D. Multiple imputation for nonresponse in surveys. John Wiley and Sons, 1987.

- 24.Kung HC, Hoyert DL, Xu J, Murphy SL. Deaths: final data for 2005. Natl Vital Stat Rep 2008;56:1-120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Adams MJ, Lipsitz SR, Colan SD, Tarbell NJ, Treves ST, Diller L, et al. Cardiovascular status in long-term survivors of Hodgkin’s disease treated with chest radiotherapy. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:3139-48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Lipshultz SE, Colan SD, Gelber RD, Perez-Atayde AR, Sallan SE, Sanders SP. Late cardiac effects of doxorubicin therapy for acute lymphoblastic leukemia in childhood. N Engl J Med 1991;324:808-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Green DM, Grigoriev YA, Nan B, Takashima JR, Norkool PA, D’Angio GJ, et al. Congestive heart failure after treatment for Wilms’ tumor: a report from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study group. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:1926-34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Postma A, Elzenga NJ, Haaksma J, Schasfoort-Van Leeuwen MJ, Kamps WA, Bink-Boelkens MT. Cardiac status in bone tumor survivors up to nearly 19 years after treatment with doxorubicin: a longitudinal study. Med Pediatr Oncol 2002;39:86-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Meinardi MT, Gietema JA, van Veldhuisen DJ, van der Graaf WT, de Vries EG, Sleijfer DT. Long-term chemotherapy-related cardiovascular morbidity. Cancer Treat Rev 2000;26:429-47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.van der Pal HJ, van Dalen EC, Kremer LC, Bakker PJ, van Leeuwen FE. Risk of morbidity and mortality from cardiovascular disease following radiotherapy for childhood cancer: a systematic review. Cancer Treat Rev 2005;31:173-85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kremer LC, van Dalen EC, Offringa M, Ottenkamp J, Voute PA. Anthracycline-induced clinical heart failure in a cohort of 607 children: long-term follow-up study. J Clin Oncol 2001;19:191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.van Dalen EC, van der Pal HJ, Kok WE, Caron HN, Kremer LC. Clinical heart failure in a cohort of children treated with anthracyclines: a long-term follow-up study. Eur J Cancer 2006;42:3191-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pein F, Sakiroglu O, Dahan M, Lebis J, Merlet P, Shamsaldin A, et al. Cardiac abnormalities 15 years and more after adriamycin therapy in 229 childhood survivors of a solid tumour at the Institut Gustave Roussy. Br J Cancer 2004;91:37-44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Velensek V, Mazic U, Krzisnik C, Demsar D, Jazbec J, Jereb B. Cardiac damage after treatment of childhood cancer: a long-term follow-up. BMC Cancer 2008;8:141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lipshultz SE, Lipsitz SR, Mone SM, Goorin AM, Sallan SE, Sanders SP, et al. Female sex and drug dose as risk factors for late cardiotoxic effects of doxorubicin therapy for childhood cancer. N Engl J Med 1995;332:1738-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watts RG. Severe and fatal anthracycline cardiotoxicity at cumulative doses below 400 mg/m2: evidence for enhanced toxicity with multiagent chemotherapy. Am J Hematol 1991;36:217-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hudson MM, Rai SN, Nunez C, Merchant TE, Marina NM, Zalamea N, et al. Noninvasive evaluation of late anthracycline cardiac toxicity in childhood cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol 2007;25:3635-43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ali MK, Ewer MS, Gibbs HR, Swafford J, Graff KL. Late doxorubicin-associated cardiotoxicity in children: the possible role of intercurrent viral infection. Cancer 1994;74:182-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Katz A, Goldenberg I, Maoz C, Thaler M, Grossman E, Rosenthal T. Peripartum cardiomyopathy occurring in a patient previously treated with doxorubicin. Am J Med Sci 1997;314:399-400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lipshultz SE, Colan SD. Cardiovascular trials in long-term survivors of childhood cancer. J Clin Oncol 2004;22:769-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lipshultz SE. Dexrazoxane for protection against cardiotoxic effects of anthracyclines in children. J Clin Oncol 1996;14:328-31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hancock SL, Donaldson SS, Hoppe RT. Cardiac disease following treatment of Hodgkin’s disease in children and adolescents. J Clin Oncol 1993;11:1208-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Reinders JG, Heijmen BJ, Olofsen-van Acht MJ, van Putten WL, Levendag PC. Ischemic heart disease after mantlefield irradiation for Hodgkin’s disease in long-term follow-up. Radiother Oncol 1999;51:35-42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.King V, Constine LS, Clark D, Schwartz RG, Muhs AG, Henzler M, et al. Symptomatic coronary artery disease after mantle irradiation for Hodgkin’s disease. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 1996;36:881-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aleman BM, van den Belt-Dusebout AW, De Bruin ML, van‘t Veer MB, Baaijens MH, de Boer JP, et al. Late cardiotoxicity after treatment for Hodgkin lymphoma. Blood 2007;109:1878-86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Huddart RA, Norman A, Shahidi M, Horwich A, Coward D, Nicholls J, et al. Cardiovascular disease as a long-term complication of treatment for testicular cancer. J Clin Oncol 2003;21:1513-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Laverdiere C, Cheung NK, Kushner BH, Kramer K, Modak S, LaQuaglia MP, et al. Long-term complications in survivors of advanced stage neuroblastoma. Pediatr Blood Cancer 2005;45:324-32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gaya AM, Ashford RF. Cardiac complications of radiation therapy. Clin Oncol (R Coll Radiol) 2005;17:153-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pohjola-Sintonen S, Totterman KJ, Salmo M, Siltanen P. Late cardiac effects of mediastinal radiotherapy in patients with Hodgkin’s disease. Cancer 1987;60:31-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Martin RG, Ruckdeschel JC, Chang P, Byhardt R, Bouchard RJ, Wiernik PH. Radiation-related pericarditis. Am J Cardiol 1975;35:216-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Carlson RG, Mayfield WR, Normann S, Alexander JA. Radiation-associated valvular disease. Chest 1991;99:538-45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Heidenreich PA, Hancock SL, Lee BK, Mariscal CS, Schnittger I. Asymptomatic cardiac disease following mediastinal irradiation. J Am Coll Cardiol 2003;42:743-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith Sehdev AE, Hutchins GM. Problems with proper completion and accuracy of the cause-of-death statement. Arch Intern Med 2001;161:277-84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Mant J, Wilson S, Parry J, Bridge P, Wilson R, Murdoch W, et al. Clinicians didn’t reliably distinguish between different causes of cardiac death using case histories. J Clin Epidemiol 2006;59:862-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Louie AD, Robison LL, Bogue M, Hyde S, Forman SJ, Bhatia S. Validation of self-reported complications by bone marrow transplantation survivors. Bone Marrow Transplant 2000;25:1191-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kadan-Lottick NS, Robison LL, Gurney JG, Neglia JP, Yasui Y, Hayashi R, et al. Childhood cancer survivors’ knowledge about their past diagnosis and treatment: childhood cancer survivor study. JAMA 2002;287:1832-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Nathan PC, Greenberg ML, Ness KK, Hudson MM, Mertens AC, Mahoney MC, et al. Medical care in long-term survivors of childhood cancer: a report from the childhood cancer survivor study. J Clin Oncol 2008;26:4401-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Other investigators and institutions participating in the Childhood Cancer Survivor Study