Abstract

RATIONALE

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) agonists, partial agonists and antagonists have antidepressant-like effects in rodent models and reduce symptoms of depression in humans.

OBJECTIVE

The aim of this study was to determine if the β2* partial agonist sazetidine-A (sazetidine) showed an antidepressant-like effect in the forced swim test that was mediated by β2* nAChRs activation or desensitization.

RESULTS

Sazetidine, the less selective β2* partial agonist varenicline and the full β2* agonist 5-I-A8350, exhibited acute antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test. The role of β2* nAChRs was confirmed by results showing 1) reversal of sazetidine’s antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test by nAChR antagonists mecamylamine and dihydro-β-erythroidine (DHβE); 2) no effect of sazetidine in mice lacking the β2 subunit of the nAChR; and 3) a high correspondence between behaviorally active doses of sazetidine and β2* receptor occupancy. β2* receptor occupancy following acute sazetidine, varenicline, and 5-I-A8350 extended beyond the duration of action in the forced swim test. The long lasting receptor occupancy of sazetidine did not diminish behavioral efficacy in the forced swim test following repeated dosing.

CONCLUSIONS

These results demonstrate that activation of β2* nAChRs mediate sazetidine’s antidepressant-like actions and suggest that ligands that activate β2* nAChRs would be promising targets for the development of a new class of antidepressant.

Keywords: nicotinic receptor, antidepressant, sazetidine-A, AMOP-H-OH, varenicline, 5-I-A85380, receptor occupancy, forced swim

Introduction

Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor (nAChR) ligands may represent a novel class of therapeutic agents for treating depression (Shytle et al. 2002). There is particularly strong support for the role of β2* nAChRs (asterisk indicates assembly with other nAChR subunits) in mediating the antidepressant-like response of nAChR ligands as well as traditional antidepressants. β2 subunit knockout mice (Picciotto et al. 1995), showed no behavioral antidepressant response to either mecamylamine (Rabenstein et al. 2006) or the tricyclic antidepressant amitriptyline, and lacked the expected increase in hippocampal cell proliferation by amitriptyline (Caldarone et al. 2004). Acute treatment with the α4β2* agonist A-85380 was effective in the mouse forced swim test (Buckley et al. 2004) and subchronic treatment with the α4β2* agonist SIB-1508Y produced an antidepressant-like response in the learned helplessness model (Ferguson et al. 2000). Administration of the α4β2* partial agonists varenicline (Rollema et al. 2009), cytisine (Mineur et al. 2007) and TC-1734 (Gatto et al. 2004) produced antidepressant-like activity in the forced swim test, and NS3956 enhanced the effects of citalopram and reboxetine in the forced swim test (Andreasen et al. 2010). Gene expression profile studies in an animal model of depression also support the role of β2* receptors in depressive responses. Social defeat, which induces depression-like behavior in rodents (Kudryavtseva et al. 1991), produced a robust increase in expression of the β2 nAChR subunit in the brain (Kroes et al. 2007). Taken together, these studies suggest that ligands that target β2* nAChRs would be effective antidepressants.

Although the role of β2* receptors in mediating the antidepressant response of nAChR ligands is well supported, it is unclear whether nAChR activation, desensitization, or some combination of both is essential (Picciotto et al. 2007). Therefore, we studied sazetidine-A (sazetidine/AMOP-H-OH) (Kozikowski et al. 2009; Xiao et al. 2006; Zwart et al. 2008), a β2* partial agonist and desensitizer that shows robust antidepressant-like properties in the forced swim test (Kozikowski et al. 2009; Turner et al. 2010). We first confirmed the role of β2* nAChRs in mediating sazetidine’s antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test. This was carried out by determining if the effects of sazeztidine in the forced were absent is β2 subunit knockout mice and whether there was a correspondence between behaviorally active doses of sazetidine and β2* receptor occupancy. Next, we confirmed whether sazetidine acted primarily via nAChR activation or desensitization of nAChRs by determining if the antidepressant-like effects of sazetidine could be blocked by administration of nAChR antagonists and if an acute dose of sazetidine would inhibit the antidepressant-like effect of a second dose. Additional studies compared how sazetidine’s behavioral effects and β2* receptor occupancy compared to the well-characterized α4β2* full agonist 5-I-A85380 and the α4β2* partial agonist varenicline.

METHODS

Animals

BALB/cJ (BALB) and C57BL/6J (C57) male mice (approximately 2–4 months of age at the time of behavioral testing) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). Mice were housed 4 to a cage in a colony room on a 12 hour light-dark cycle maintained at 22°C (±3) with a relative humidity between 30% and 70%. β2 subunit knockout (KO), heterozygous (HET), and wild-type (WT) littermate male mice (between 4 and 13 months of age at testing) were bred more than 30 generations on to a C57 background. All animal experiments were conducted in accordance with the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (NRC 1996) and the PsychoGenics and Yale University Animal Care and Use Committees.

Drug Treatments

Sazetidine-A (6-(5-(S)-azetidin-2-yl)methoxypyridine-3-yl)hex-5-yn-1-ol) was synthesized according to published methods (Kozikowski et al. 2009). Mecamylamine hydrochloride, methyllycaconitine citrate hydrate (MLA), dihydro-beta-erythroidine hydrobromide (DHβE), and desipramine hydrochloride were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO), sertraline hydrochloride from Toronto Research Chemicals (Ontario, Canada), varenicline tartrate from Allichem (Savage, MD) and 5-Iodo-A-85380 (5-I-A85380) dihydrochloride from Tocris Bioscience (Ellisville, MO). All drugs were dissolved in either saline, phosphate buffered saline, or injectable water and injected intraperitoneally (i.p) in a volume of 10 ml/kg. All doses are expressed as salt except for varenicline, which is expressed as the freebase.

5-I-A85380, varenicline, and sazetidine in the mouse forced swim test

Mice were placed individually into clear glass cylinders (i.e., 15 cm tall × 10 cm wide, 1 L beakers) containing 23 ± 1 °C water 12 cm deep (approximately 800 ml). The time the animal spent immobile was recorded over a 6 min trial. Immobility was described as the postural position of floating in the water.

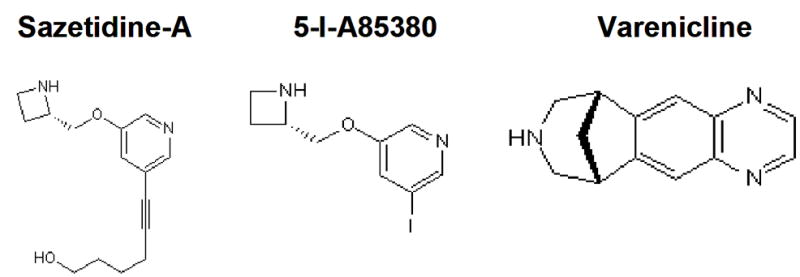

The antidepressant-like effects of the α4β2* full agonist 5-I-A85380 and the α4β2* partial agonists varenicline and sazetidine were compared in the forced swim test (see Figure 1 for structures). 5-I-A85380 and sazetidine were tested in the BALB strain and varenicline was tested in both BALB and C57 mice. Mice received a 30 min pretreatment with either 5-I-A85380 (0, 0.03, 0.1, 0.3 mg/kg) (n=8/group), varenicline (0, 0.3, 1, or 3 mg/kg) (n=9–10/group, BALB; (n = 10/group, C57), or sazetidine (0, 0.3, 1, 3, or 10 mg/kg) (n = 9–10/group). Positive controls were sertraline (10 mg/kg) in BALB mice and desipramine (20 mg/kg) in C57 mice.

Figure 1.

Chemical structural representations of sazetidine-A (A), varenicline (B) and 5-I-A85380 (C).

Sazetidine: Ex vivo binding to assess receptor occupancy of β2* nAChRs and potency in the forced swim test

To determine if β2* nAChR subunits mediate the behavioral effects of sazetidine in the forced swim test, occupancy of β2* nAChRs binding sites in the brain were compared with behavioral efficacy in the forced swim test. Sazetidine (0.3, 1, and 3 mg/kg) or vehicle was administered 30 min before brain collection (the same time point as forced swim testing) for analysis of receptor occupancy of the thalamus (n = 3/group). An additional group of mice was administered sazetidine (3mg/kg) or vehicle 30 min before brain collection for analysis of receptor occupancy various brain regions (thalamus, amygdala, prefrontal cortex (PFC), and the dorsal striatum) (n=4/group).

Mouse brains were sectioned with a Leica CM3050S cryostat (Leica, Germany). 20 μm sections were mounted on a poly-Lysine coated slide and instantly dried with a slide warmer. Six sections were taken in total with adjacent sections 300 μm apart.

[3H]-Cytisine binding

Matching sections from vehicle and drug treated mice were incubated with 1nM [3H]-Cytisine (Perkin Elmer, CT) on ice for 30 min in a binding buffer consisting of 50mM TrisHCl pH7.4, 120mM NaCl, 5mM KCl, 1mM MgCl2, 2.5mM CaCl2. After incubating, the slides were washed twice (1 min each wash) in ice cold binding buffer, dipped in ice cold deionized water and dried under a stream of cool air. Non-specific binding was not performed, due to the high specific binding for the ligand (98%).

Beta-imaging

Aluminum tapes were placed on the back of dried slides, the slides were loaded into the beta-imager 2000 (Biospace Lab, FR) and the images of the brains slices were acquired overnight.

Data quantification and receptor occupancy calculation

The intensity of [3H]-Cytisine binding in from vehicle or drug treated mice was quantified with beta-version+ software (Biospace Lab, FR).

Assessment of the role of β2* nAChRs in the antidepressant-like effects of sazetidine in the forced swim test

To confirm the role of β2* nAChRs in mediating the behavioral effects of sazetidine in the forced swim test, both pharmacological antagonists and genetic approaches were utilized. For pharmacological antagonist testing, BALB mice were administered either the non-selective, non-competitive nAChR antagonist mecamylamine (1 mg/kg) (n=10/group), the competitive α4β2/α4β4 nAChR antagonist dihydro-beta-erythroidine (Harvey et al. 1996), (DHβE; 3 mg/kg) (n=9–10/group) or the α7 antagonist methyllycaconitine (MLA; 10 mg/kg) (n=9–10/group), 5 min before treatment with sazetidine (3 mg/kg for mecamylamine study, and 1mg/kg for DHβE and MLA studies). For genetic testing, the effects of sazetidine (1 mg/kg, 30 min pretreatment) in the forced swim test were compared in the KO, HET, and WT littermates of mice lacking the β2 subunit of the nAChR (n = 5–8/group).

Sazetidine: Comparison of duration of action in the forced swim test, β2* ex vivo receptor occupancy, and drug levels in plasma and brain

The time course of sazetidine in the forced swim test was measured to determine if the duration of action in this test corresponded with sazetidine’s pharmacokinetic and receptor occupancy profile. BALB mice were tested in the forced swim assay following a 2, 3, 4, or 5 h pretreatment with either sazetidine (1 mg/kg) or vehicle (vehicle, n = 18; 2, 3, 4h pretreatment, n = 10/group; 5 h pretreatment, n = 6).

To determine the nAChR occupancy profile, BALB mice were treated with sazetidine (1 or 3mg/kg) and brains were collected 0.25, 4, 8, and 24 h following drug administration for ex vivo receptor occupancy studies (n = 5–6/group).

To determine the pharmacokinetic profile of sazetidine, BALB mice were treated with sazetidine (1 and 3 mg/kg) for 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, or 4 h (n = 3/group) before collection of trunk blood and brain samples. Concentrations of sazetidine were determined by reverse phase HPLC (Enthalpy Analytical Inc, Durham, NC).

5-I-A85380 and varenicline: Comparison of duration of action in the forced swim test and β2* ex vivo receptor occupancy

The effects a well-characterized α4β2* nAChR partial agonist (varenicline) and full agonist (5-I-A85380) were tested to determine the duration of action in the forced swim and the duration of receptor occupancy. BALB mice were administered 5-I-A85380 (0.3 mg/kg) or vehicle (n=10–12/group) and C57 mice were administered varenicline (0.3 mg/kg) or vehicle 0.5, 4, or 8 h before forced swim testing (n=8–12/group). Brains were collected for ex vivo receptor occupancy studies under the same conditions from a separate set of mice for 5-I-A85380 (0.3 mg/kg) in BALB mice (n = 5/group) and varenicline (0.3 mg/kg) in C57 mice (n = 4–5/group).

Assessment of behavior in the forced swim and locomotor activity tests following repeated administration of sazetidine

To determine whether repeated administration of sazetidine would produce behavioral tolerance in the forced swim test, BALB mice were administered sazetidine (1 or 3 mg/kg), sertraline (10 mg/kg) or vehicle once a day for 13 days and a final injection on the 14th day was given 30 min before forced swim testing (n = 9–10/group). “Acute” tolerance to sazetidine was determined by administering an 8 h pretreatment with either sazetidine (3 mg/kg) or vehicle and then administering a second dose of sazetidine (3 mg/kg) or vehicle 30 min before behavioral testing (n = 9–10/group). An 8 h pretreatment was chosen because high receptor occupancy did not translate into behavioral efficacy in the forced swim test at this time point. A subset of brains (n = 3/group) was collected immediately following the “acute tolerance” testing to access receptor occupancy.

Locomotor activity was assessed to determine if chronic administration of sazetidine altered locomotor activity. Locomotor activity was measured in Plexiglas square chambers (27.3 × 27.3 × 20.3 cm; Med Associates Inc., St Albans, VT) surrounded by infrared photobeams. Mice were administered sazetidine (1 or 3 mg/kg) or vehicle for two weeks and approximately 1 day after the last injection, mice were placed into the open field and locomotor activity was measured for 30 min. Mice were then administered either vehicle or sazetidine (1 or 3 mg/kg) and activity was measured for an additional 30 min (n=11–12/group).

Statistical Analyses

All data were analyzed with analysis of variance (ANOVA) with dependent variables as follows: forced swim test, total time immobile (sec/6 min); locomotor activity, distance traveled (cm/30min) pre and post drug administration; receptor occupancy, percent occupancy. All significant main effects and interactions were followed up with the Student Newman-Keuls post hoc test. An effect was considered significant if p<0.05 (Statview for Windows, Version 5.0).

RESULTS

5-I-A85380 and varenicline produced antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test

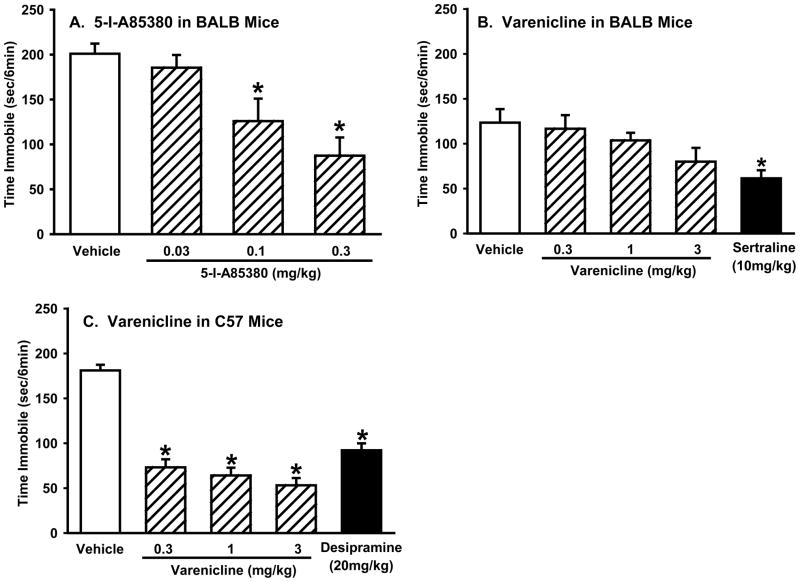

5-I-A85380 dose dependently decreased immobility in BALB mice (one-way ANOVA: F(3,28)=8.4, p<0.001), with significant decreases seen at 0.1 and 0.3 mg/kg but no effect of the 0.03 mg/kg dose (Figure 2A). Varenicline did not decrease immobility in BALB mice (one-way ANOVA: F(3,34)=1.8, p>0.1), although sertraline (10 mg/kg) produced the expected reduction in immobility (one-way ANOVA: F(1,18)=12.4, P<0.01) (Figure 2B). Varenicline reduced immobility in the C57 strain (one-way ANOVA: F(3,36)=53.9, p<0.0001) with significant reductions seen at all doses tested (0.3, 1, and 3 mg/kg), confirming the antidepressant-like activity in this strain (Rollema et al. 2009). Desipramine (20 mg/kg) produced the expected reduction in immobility in the C57 strain (one-way ANOVA: F(1,18)=79.0, P<0.0001) (Figure 2C). In addition to the partial agonists action at α4β2* receptors, varenicline is a full agonist at α7 receptors (Mihalak et al. 2006), an effect that could explain the strain differences in the response to varenicline in the forced swim test.

Figure 2. Acute treatment with 5-I-A85380 or varenicline has antidepressant-like activity in the forced swim test.

(A) Effects of 5-I-A85380 (0, 0.03, 0.1, or 0.3 mg/kg) in BALB mice in the forced swim test; (B) Effects of varenicline (0, 0.3, 1, or 3 mg/kg) and sertraline (10mg/kg) in BALB mice in the forced swim test. (C) Effects of varenicline (0, 0.3, 1, or 3 mg/kg) or desipramine (20 mg/kg) in C57 mice in the forced swim test. Values represent mean time immobile ±SEM. Asterisks (*p<0.05) indicate significant differences compared to vehicle.

Sazetidine produced high levels of β2* receptor occupancy that corresponded to potency in the mouse forced swim test

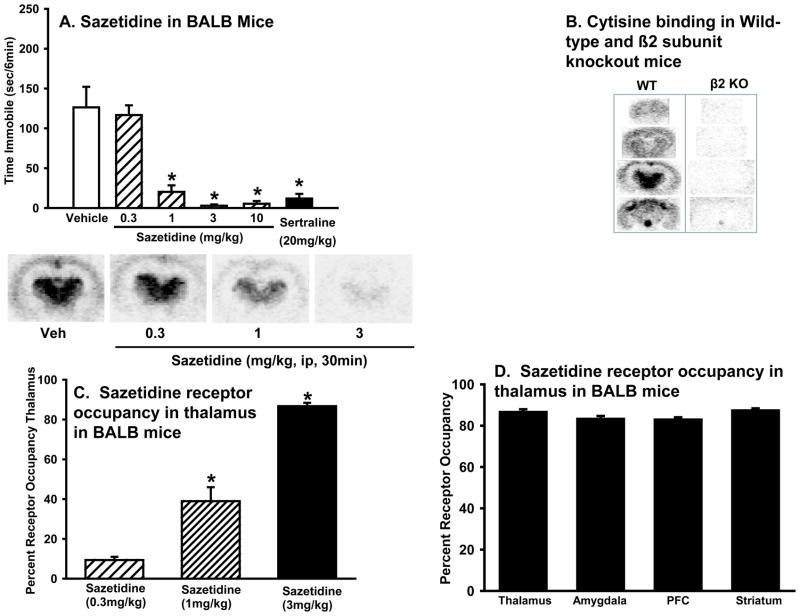

Sazetidine dose dependently reduced immobility in BALB mice (one-way ANOVA: F(4,44)=23.6, p<0.0001) (Figure 3A), with significant reductions seen at 1, 3, and 10 mg/kg, but not 0.3 mg/kg. The magnitude of the antidepressant-like response of the active doses of sazetidine was similar to that produced by sertraline (20 mg/kg; one-way ANOVA: F(1,17)=20.8, p<0.001).

Figure 3. Acute treatment with sazetidine has antidepressant-like activity in the forced swim test that corresponds with levels of β2* receptor occupancy in the brain.

(A) Effects of sazetidine (0, 0.3, 1, 3, or 10 mg/kg) or sertraline (20 mg/kg) in BALB mice in the forced swim test. Values represent mean time immobile ±SEM. Asterisks (*p<0.05) indicate significant differences compared to vehicle. (B) [3H]-Cytisine binding in various brain regions in wild type (WT) mice and knockout mice lacking the β2 subunit of the nAChR (β2 KO). (C) [3H]-Cytisine binding in the thalamus following sazetidine (0.3, 1, or 3 mg/kg) treatment. Data represent the mean (±SEM) percent receptor occupancy in the thalamus. Asterisks (*p<0.5) indicate differences from sazetidine (0.3 mg/kg). Images of representative brain slices are shown. It should be noted that receptor occupancy is calculated as competition of [3H]-Cytisine and cold sazetidine so that darker images correspond to lower occupancy. (D)[3H]-Cytisine binding following sazetidine (3 mg/kg) treatment in the thalamus, amygdala, prefrontal cortex (PFC), and dorsal striatum.

An ex vivo receptor occupancy study determined if the behavioral potency of sazetidine corresponded to the specific binding at β2* receptors. [3H]-Cytisine (1 nM) showed no specific binding in sections from the thalamus, amygdala, PFC, or striatum from β2 KO mice[3H]-demonstrating specific binding to β2* (Figure 3B). The Ki value for sazetidine binding (displacement of [3H]-Cytisine) to β2* nAChRs in the thalamus of WT mice was 0.2 nM (data not shown).

At 30 min after drug administration, a dose of sazetidine that was inactive in the forced swim test (0.3 mg/kg) resulted in very low levels of β2* nAChRs occupancy (~10%). In contrast, doses of sazetidine that produced efficacy in forced swim resulted in higher levels of receptor occupancy (~40% at 1 mg/kg; ~90% at 3 mg/kg). ANOVA confirmed that receptor occupancy varied according to dose (one-way ANOVA: F(3,8)=82.2, p<0.0001) with post hoc tests showing that the 0.3 mg/kg dose was not different from vehicle but that all other doses of sazetidine were significantly different from each other and from vehicle (Figure 3C). Analysis of receptor occupancy 30 min following a 3 mg/kg dose of sazetidine showed no differences between occupancy in the thalamus, amygdala, PFC or striatum. Although ANOVA showed a trend for differences between occupancy in various brain regions (one-way ANOVA: F(3,12)=3.3, p=.057) post hoc tests did not reveal any differences in occupancy in various brain regions. Therefore, the thalamus was used for quantification of receptor occupancy for all subsequent studies (Figure 3D).

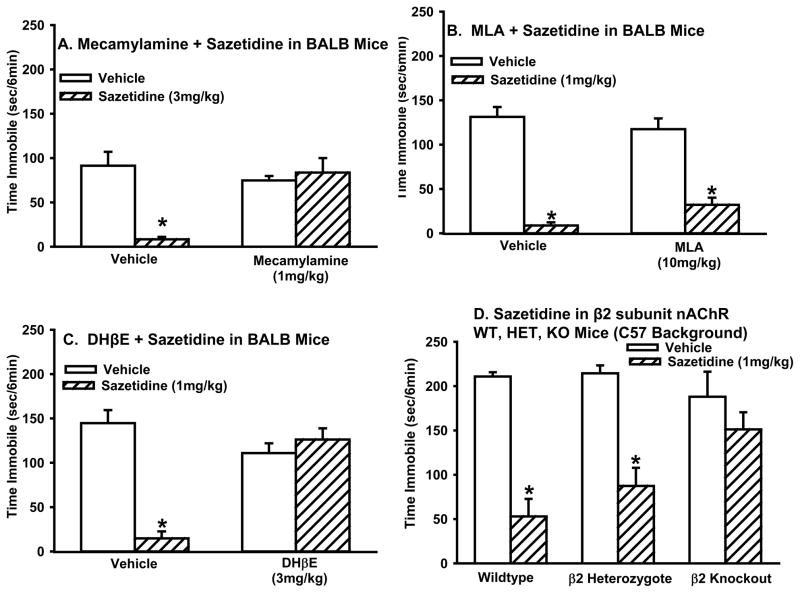

Sazetidine’s antidepressant-like effects in the forced swim test require β2* nAChRs

Mecamylamine completely blocked the antidepressant-like effect of sazetidine (two-way ANOVA: sazetidine × mecamylamine interaction (F(1,36)=15.4, p<0.001)). Sazetidine treated mice spent less time immobile compared to vehicle treated mice, but mice pretreated with mecamylamine were indistinguishable from vehicle treated mice (Figure 4A). These results demonstrate the nAChRs mediate the behavioral effects of sazetidine in the forced swim test.

Figure 4. The antidepressant-like activity of sazetidine is mediated by β2* receptors.

Effects of pretreatment with (A) mecamylamine (1 mg/kg); (B) MLA (10 mg/kg;), or (C) DHβE (3 mg/kg) on sazetidine’s (3 mg/kg (A) or 1 mg/kg (B and C)) antidepressant-like activity in the forced swim test. (D) Effects of sazetidine (1mg/kg) in the forced swim test in β2 subunit wild type, heterozygous or knockout mice (C57 background). Values represent mean time immobile ±SEM. Asterisks (*p<0.05) indicate significant differences compared to vehicle.

MLA did not block the antidepressant-like effect of sazetidine. Sazetidine reduced immobility in mice both with and without MLA pretreatment (main effect of sazetidine treatment (two-way ANOVA: F(1,35)=121.7, p<0.0001). Although the sazetidine × MLA interaction (two-way ANOVA: F(1,35)=3.9, p=.057) approached significance, post hoc tests showed that mice treated with MLA and sazetidine were not statistically different from mice treated with sazetidine alone (Figure 4B). These results suggest that α7 nAChRs are not involved in the behavioral effects of sazetidine in the forced swim test and are consistent with in vitro displacement binding data showing that sazetidine, at a concentration of 10 μM does not displace [125H] alpha-bungarotoxin binding (Cerep, catalog # 0567;(Sharples et al. 2000)).

DHβE completely blocked the antidepressant-like effect of sazetidine (sazetidine × DHβE interaction (two-way ANOVA: F(1,34)=37.5, p<0.0001). Sazetidine-treated mice spent less time immobile compared to vehicle treated mice, but mice that were pretreated with DHβE were indistinguishable from vehicle treated mice (Figure 4C). These results suggest that heteromeric nAChRs mediate the behavioral effects of sazetidine in the forced swim test.

β2 subunit KO mice did not respond to sazetidine in the forced swim (genotype × drug interaction (two-way ANOVA: F(2,34)=5.0, p<0.05). Sazetidine decreased immobility in both WT and HET mice, but KO mice treated with sazetidine were not different than vehicle controls (Figure 4D). These results confirm the role of β2* nAChRs in mediating the behavioral effects of sazetidine in the forced swim test.

Sazetidine showed a dissociation between duration of action in the mouse forced swim test, pharmacokinetic profile, and β2* receptor occupancy in the brain

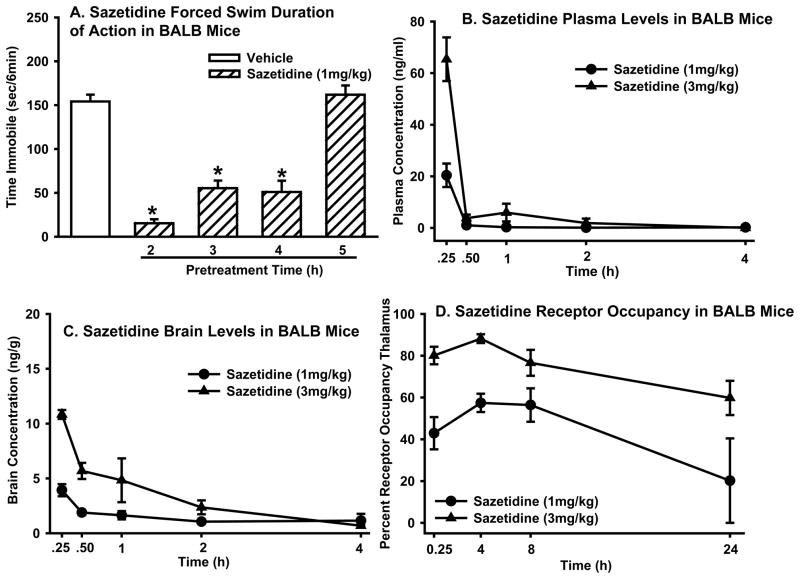

Sazetidine was long acting in the forced swim test with behavioral activity observed up to 4 h after pretreatment (one-way ANOVA: F(4,49)=50.5, p<0.0001) (pretreatment time did not influence immobility time in vehicle treated mice so all vehicle mice were combined analyses). Sazetidine (1mg/kg) significantly reduced immobility following 2, 3, and 4 h pretreatment, but activity was completely gone by 5 h (Figure 5A). The effects of sazetidine at a 3 mg/kg dose are also present at 4hr (data not shown) and completely absent by 8h (Figure 7B).

Figure 5. Dissociation between sazetidine duration of action in the forced swim test pharmacokinetic profile, and time course of β2* receptor occupancy.

(A) Effects of sazetidine (1mg/kg) in the forced swim test following 2, 3, 4, or 5 h pretreatment. Values represent mean time immobile ±SEM. Asterisks (*p<0.05) indicate significant differences compared to vehicle treatment. Plasma levels (ng/ml) (B) and brain levels (ng/g) (C) of sazetidine (1 or 3 mg/kg) following 0.25, 0.5, 1, 2, and 4 h pretreatment. Data represent the mean (±SEM) sazetidine levels. (D) [3H]-Cytisine binding following sazetidine (1 or 3 mg/kg) pretreatment (0.25, 4, 8, or 24 h). Data represent the mean (±SEM) percent receptor occupancy in the thalamus.

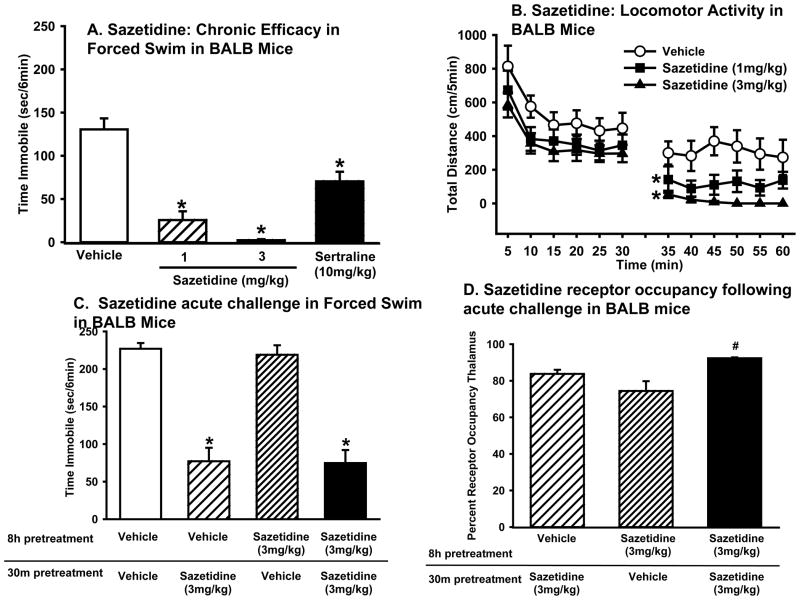

Figure 7. Sazetidine administration results in neither acute nor chronic tolerance, despite high levels of β2* receptor occupancy in the thalamus.

(A) Effects of a 2 week pretreatment of vehicle, sazetidine (1 or 3 mg/kg) or sertraline (10 mg/kg) followed by an acute 30 min challenge dose (n = 10/group) of sazetidine in the forced swim test. Data represent mean time immobile ±SEM. Asterisks (*p<0.05) indicate significant differences compared to vehicle (B) Effect of sazetidine (1 or 3 mg/kg) on locomotor activity following two week treatment prior to (0–30 min) and following a challenge dose (35–60 min) of sazetidine. Data represent mean distance traveled ±SEM. Asterisks (*p<0.05) indicate significant differences (35 –60 min collapsed) compared to vehicle. (C) Effects of an 8h pretreatment with either vehicle or sazetidine (3 mg/kg) and a second challenge injection of vehicle or sazetidine (3 mg/kg) 30 min before forced swim testing. Data represent mean time immobile ±SEM. Asterisks (*p<0.05) indicate significant differences compared to vehicle. (D) [3H]-Cytisine binding in a subset of mice from (C). Data represent the percent receptor occupancy ±SEM in the thalamus. Symbol (#p<0.05) indicates significant differences compared to sazetidine-vehicle.

Plasma and brain levels of sazetidine did not correspond to duration of action in the forced swim test. Although plasma levels showed a dose response relationship 15 min after administration (~20 ng/ml at 1 mg/kg, and ~60 ng/ml at 3 mg/kg), levels were nearly non-detectable by 30 min after administration (Figure 5B). Brain levels of sazetidine reached low levels 15 min after administration (~3 ng/g at 1 mg/kg and ~10 ng/g at 3 mg/kg) and were at or below detection level at the later time points (Figure 5C).

Because duration of action of sazetidine in the forced swim test did not correspond to plasma and brain levels of the drug, ex vivo β2* receptor occupancy in the thalamus was measured to determine if the time course of behavioral efficacy of sazetidine could be explained by occupancy of sazetidine at β2* receptors. Results showed a very slow dissociation rate of sazetidine from β2* receptors, with receptor occupancy varying according to dose and time (two-way ANOVA: treatment (1 or 3 mg/kg sazetidine) × time (0.25, 4, 8, 24 h) interaction (F(3,36)=4.3, p<0.05)]. Surprisingly, between 15 min and 4 h post dosing, receptor occupancy of both the 1 and 3 mg/kg doses of sazetidine increased by ~10%, but the increase reached statistical significance only for the 1 mg/kg dose (Figure 5D).

Although sazetidine was not behaviorally active in the forced swim test 8 h post-dosing, the receptor occupancy rates remained high at 8 h (~50% at 1 mg/kg, and ~80% at 3 mg/kg), and 24 h (~60% for the 3 mg/kg) post administration (Figure 5D). The high receptor occupancy of 3 mg/kg at 8 h post administration, however, did not translate to efficacy in the forced swim test (Figure 7C).

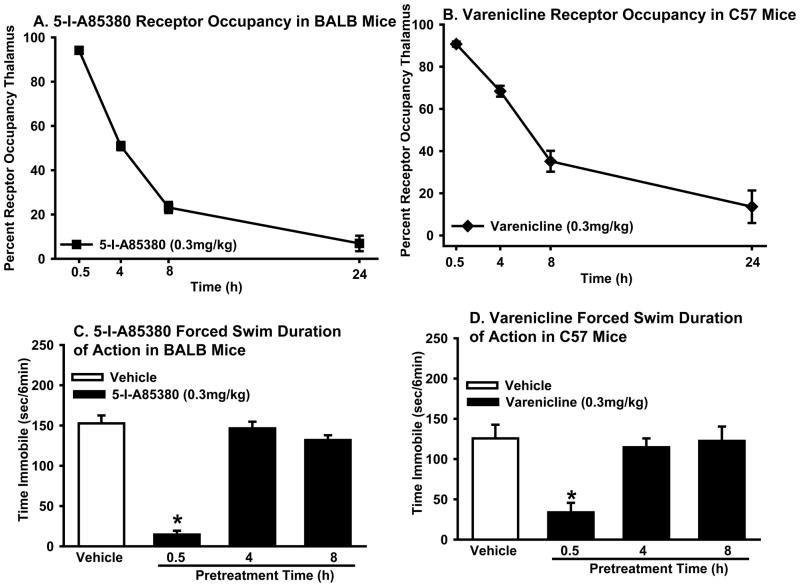

Varenicline and 5-I-A85380 showed a dissociation between duration of action in the mouse forced swim test and β2* receptor occupancy in the brain

Sazetidine’s receptor occupancy time course was compared with varenicline and 5-I-A85380, a compound with a core structure similar to sazetidine without sazetidine’s side chain (Figure 1). Doses of 5-I-A85380 (0.3 mg/kg) (Figure 2A) and varenicline (0.3 mg/kg) (Figure 2C) that were behaviorally active in the forced swim test were administered to mice and brains were harvested 0.5, 4, 8, and 24 h after drug administration. Results showed that both 5-I-A85380 (Figure 6A) and varenicline (Figure 6B) produced high levels of receptor occupancy at β2* receptors that varied across time (one-way ANOVA: 5-I-A85380: F(3,16)=258.7, p<0.0001; (one-way ANOVA: varenicline: F(3,15)=58.8, p<0.0001). Similar to sazetidine, both compounds produced very high levels of receptor occupancy at 30 min after drug administration, but unlike sazetidine, levels of occupancy diminished with each time point over 24 h. Both varenicline and 5-I-A85380 appeared to follow single site, one phase dissociation kinetics with the dissociation half life of varenicline ~5.4 h and 5-I-A85380 ~3.4 h. The short dissociation half life of 5-I-A85380 supports the hypothesis that the structural side chain of sazetidine likely contributes to its long receptor occupancy.

Figure 6. 5-I-A85380 and varenicline: β2* receptor occupancy in the brain is prolonged compared to duration of action in the forced swim test.

[3H]-Cytisine binding in mice administered 0.5, 4, 8, or 24 h pretreatment with (A) 5-I-85380 (0.3 mg/kg) or (B) varenicline (0.3 mg/kg). Data represent the mean (±SEM) percent receptor occupancy in the thalamus. Effects of 5-I-A85380 (0.3 mg/kg) (C) or varenicline (0.3 mg/kg) (D) following a 0.5, 4, or 8h pretreatment in the forced swim test. Data represent mean time immobile ±SEM. Asterisks (*p<0.05) indicate significant differences compared to vehicle.

The antidepressant-like effect of 5-I-A85380 (one-way ANOVA: F(3,38)=69.0, p<0.0001) and varenicline (one-way ANOVA: F(3,36)=7.0, p<0.001) (pretreatment time did not influence immobility time in vehicle treated mice so all vehicle mice were combined analyses) varied across time, with activity for both compounds seen at 0.5 h but not at 4 or 8 h after treatment. Like sazetidine, the duration of action of 5-I-A85380 (Figure 6C) and varenicline (Figure 6D) was short (0.5 h) compared to the receptor occupancy profile which showed high levels of binding (~70%) up to 4 h after treatment. These results suggest that prolonged binding at β2* receptors, extending beyond the duration of action in the forced swim test, may be a common feature of nicotinic agonists and partial agonists.

Sazetidine did not produce tolerance in the forced swim test

To determine if the prolonged binding of nAChR ligands would inhibit behavioral activity with repeated administration, we tested whether sazetidine would produce tolerance following chronic administration or following two acute injections, spaced 7.5 h apart. Sazetidine did not produce tolerance following chronic, once a day administration for two weeks. Sazetidine reduced immobility (one-way ANOVA: F(2,27)=52.9, p<0.0001) at both the 1 and 3 mg/kg doses following chronic administration to the same extent as acute dosing. Sertraline also produced the expected reduction in immobility following chronic treatment (one-way ANOVA: F(1,18)=12.5, p<0.01) (Figure 7A).

Chronic treatment with sazetidine did not affect baseline locomotor activity (one-way ANOVA: F(2,32)=1.88, p=.170) but an acute challenge decreased locomotor activity (one-way ANOVA: F(2,32)=6.70, p<0.01). Post hoc tests showed that the acute administration of both the 1 and 3 mg/kg doses of sazetidine produced a small decrease in locomotion (Figure 7B).

Sazetidine also did not produce acute tolerance with two doses administered at a 7.5 h interval (two-way ANOVA: significant main effect of the second drug treatment (F(1,35)=101.1, p<0.0001) with no significant main effect of the first treatment or interaction between the two treatments). Post hoc tests confirmed that the second dose of sazetidine reduced immobility equally in mice that received vehicle or sazetidine pretreatment (Figure 7C). Immediately following forced swim testing, a subset of brains was collected for assessment of receptor occupancy. Results showed that receptor occupancy varied according to sazetidine treatment (one-way ANOVA: F(2,6)=7.0, p<0.05). Post hoc tests showed that the level of receptor occupancy was increased in mice that received both the 8 h pretreatment and the challenge dose of sazetidine 30 min before forced swim testing (92% β2* nAChR occupancy) compared to mice that just received the 8 h pretreatment with sazetidine (74% β2* nAChR occupancy) (Figure 7D).

DISCUSSION

Sazetidine showed an acute antidepressant-like effect in BALB mice consistent with previous reports of activity in the forced swim test in both C57 (Kozikowski et al. 2009) and 129SvJ;C57BL/6J F1 hybrid mice (Turner et al. 2010). Sazetidine also exhibited an antidepressant-like profile following acute administration in the tail suspension test and following chronic, but not acute, treatment in the novelty-induced hypophagia paradigm (Turner et al. 2010), a response consistent with traditional antidepressants (Dulawa and Hen 2005). Sazetidine is a potent analgesic (Cucchiaro et al. 2008), with minimal abuse liability as indicated by weak positive reinforcing properties (Paterson et al.) and the lack of locomotor sensitization seen in the present study. Sazetidine may also have potential as an aid for smoking cessation and alcohol abuse, as indicated by data showing that sazetidine can reduce nicotine and ethanol self administration (Levin et al. 2010; Rezvani et al. 2010). These findings suggest that sazetidine-like molecules may have advantages over traditional antidepressants by treating pain, nicotine and alcohol dependence.

Sazetidine’s activity in the forced swim test is dependent on heteromeric nAChR as shown by blockade with mecamylamine and DHβE (Harvey et al. 1996), but not by the α7 antagonist MLA. The role of β2* nAChR was confirmed by results showing that sazetidine was inactive in β2 KO mice, although WT mice exhibited the expected antidepressant-like response. Ex vivo receptor occupancy studies, which showed a high correspondence between β2* receptor occupancy and potency of sazetidine in the forced swim test, further confirmed the role of β2* nAChR. Specifically, sazetidine was inactive in the forced swim test at 0.3 mg/kg and showed very low receptor occupancy at this dose (<10%). In contrast, doses of sazetidine that produced robust behavioral activity in the forced swim test corresponded with high levels of occupancy at β2* nAChRs (~40% at 1 mg/kg and ~90% at 3 mg/kg, 30 m post drug administration). These results suggest that ~10– 40% of β2* receptor occupancy is required upon initial exposure of sazetidine to achieve behavioral efficacy in the forced swim test.

The behavioral actions of sazetidine were short (4 h) compared to its receptor occupancy profile (up to 8 h for the 1 mg/kg dose and up to 24 h for the 3 mg/kg dose), but long in comparison to its pharmacokinetic profile (brain and plasma levels were not detectable by 30 min). This dissociation appears to be a common feature among β2* nAChR agonists and partial agonists as both 5-I-A85380 and varenicline also showed prolonged β2* nAChRs binding compared to their duration of action in the forced swim test. Sazetidine produced the longest β2* receptor occupancy (dissociation half life of ~8–24 h) in contrast to varenicline and 5-I-A85380 (dissociation half life of ~3–5 h). Despite prolonged β2* receptor occupancy, repeated sazetidine administration did not diminish the behavioral response in the forced swim test, demonstrating that sazetidine does not produce tolerance.

Several hypotheses might explain the dissociation between sazetidine’s duration of action, pharmacokinetics, and receptor occupancy. First, sazetidine may directly mediate the antidepressant-like effect in the forced swim as low levels of sazetidine, undetectable in whole brain, could be sufficient to produce high receptor binding. Second, the behavioral actions of sazetidine could be mediated by an active metabolite that binds to β2* nAChRs, although preliminary analysis detected no potential metabolites present at high levels in the brain (data not shown). Third, the discordance could be explained by desensitization (Ke et al. 1998; Reitstetter et al. 1999) but this explanation is not supported by our current findings that suggest an activation mechanism. Finally, downstream signaling mechanisms could inhibit antidepressant effect at later time points.

The results of the present study suggest that β2* nAChR activation is required for sazetidine’s antidepressant-like activity in the forced swim test as pretreatment with nAChRs antagonists mecamylamine or DHβE completely blocked sazetidine’s behavioral activity. As sazetidine is also a potent desensitizer in vitro, (Xiao et al. 2006; Zwart et al. 2008), it is possible that activation followed by sustained desensitization is critical to the long lasting antidepressant-like effects of sazetidine. However, our finding that a challenge dose of sazetidine given 7.5h following the initial dose is equally efficacious as a single dose of sazetidine in the forced swim test suggests that the nAChRs are not desensitized by the initial dose of sazetidine.

There is much evidence to support the hypothesis that blockade of nAChR is responsible for the antidepressant action of nicotinic ligands (Mineur and Picciotto 2010; Shytle et al. 2002). Clinical studies have shown that the cholinesterase inhibitor, physostigmine, produces depressive symptoms in humans (Janowsky et al. 1972) and that mecamylamine (George et al. 2008) and the muscarinic antagonist scopolamine (Drevets and Furey 2010; Furey and Drevets 2006) relieve depressive symptoms in humans. Preclinical studies provide additional support for the hypothesis that increased cholinergic activity leads to depressed mood states. Flinders sensitive rats, a line selectively bred for increased cholinergic sensitivity, exhibit several depressive-like behaviors (Overstreet 1986; Pucilowski et al. 1993).

Although the current findings, which suggest that sazetidine’s antidepressant effects are mediated by activation of nAChRs, appear in contrast to previous literature, it is possible that nAChR agonists and antagonists may both exert antidepressant action, but through independent mechanisms (Andreasen and Redrobe 2009). For example, both nicotine and mecamylamine have been shown to increase 5-HT release but presumably through distinct mechanisms (Kenny et al. 2000). Sazetidine may produce antidepressant-like effects by increasing NE and DA (Zwart et al. 2008), an effect that typically is not induced by nAChR antagonists. Furthermore, a balance of activation and inactivation in different brain regions may be critical in mediating the antidepressant effects of nicotinic ligands (Mineur and Picciotto 2010). Finally, various mouse strains or species may be more sensitive to detecting agonist or antagonist nicotinic antidepressant-like responses. For example, C57 are sensitive to the antidepressant-like effects of mecamylamine (Caldarone et al. 2004; Rabenstein et al. 2006) and varenicline (Rollema et al. 2009) but the BALB strain was insensitive to both in the present study. In addition, although mice show antidepressant like responses to both nAChR agonists(Buckley et al. 2004) and antagonists (Andreasen et al. 2008; Andreasen and Redrobe 2009; Caldarone et al. 2004; Lippiello et al. 2008; Mineur et al. 2007; Rabenstein et al. 2006), rats tend to exhibit greater sensitivity to the antidepressant-like effect of agonists (nicotine) rather than antagonists such as mecamylamine (Djuric et al. 1999; Semba et al. 1998; Tizabi et al. 1999; Tizabi et al. 2000; Vieyra-Reyes et al. 2008). It is likely that similar variations in responses to nicotinic agonists and antagonists will be observed in the human population.

These studies demonstrate that sazetidine’s robust activity in a behavioral model of antidepressant efficacy is mediated by β2* nAChRs and that activation of a small population of non-occupied β2* nAChRs (10–40%) is sufficient to elicit full behavioral antidepressant-like responses. Thus, activation of β2* nAChRs may be a trigger mechanism for crucial downstream effects such as CREB activation this is critical for both nicotine mediated conditioned reward (Brunzell et al. 2009) and antidepressant responsiveness (Carlezon et al. 2005). Understanding the mechanism by which nicotinic ligands such as sazetidine their antidepressant-like effects could lead to the development of novel antidepressants that could address unmet medical needs such as efficacy in treatment resistant populations.

Acknowledgments

Portions of this work were supported by MH085193 to APK. MRP was supported by MHMH77681.

References

- Andreasen JT, Nielsen EO, Christensen JK, Olsen GM, Peters D, Mirza NR, Redrobe JP. Subtype-selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonists enhance the responsiveness to citalopram and reboxetine in the mouse forced swim test. J Psychopharmacol. 2010 doi: 10.1177/0269881110364271. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen JT, Olsen GM, Wiborg O, Redrobe JP. Antidepressant-like effects of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor antagonists, but not agonists, in the mouse forced swim and mouse tail suspension tests. J Psychopharmacol. 2008;23:797–804. doi: 10.1177/0269881108091587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen JT, Redrobe JP. Antidepressant-like effects of nicotine and mecamylamine in the mouse forced swim and tail suspension tests: role of strain, test and sex. Behav Pharmacol. 2009;20:286–95. doi: 10.1097/FBP.0b013e32832c713e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreasen JT, Redrobe JP. Nicotine, but not mecamylamine, enhances antidepressant-like effects of citalopram and reboxetine in the mouse forced swim and tail suspension tests. Behav Brain Res. 2009;197:150–156. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunzell DH, Mineur YS, Neve RL, Picciotto MR. Nucleus accumbens CREB activity is necessary for nicotine conditioned place preference. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2009;34:1993–2001. doi: 10.1038/npp.2009.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckley MJ, Surowy C, Meyer M, Curzon P. Mechanism of action of A-85380 in an animal model of depression. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2004;28:723–30. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2004.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldarone BJ, Harrist A, Cleary MA, Beech RD, King SL, Picciotto MR. High-affinity nicotinic acetylcholine receptors are required for antidepressant effects of amitriptyline on behavior and hippocampal cell proliferation. Biol Psychiatry. 2004;56:657–64. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlezon WA, Jr, Duman RS, Nestler EJ. The many faces of CREB. Trends Neurosci. 2005;28:436–45. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2005.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cucchiaro G, Xiao Y, Gonzalez-Sulser A, Kellar KJ. Analgesic effects of Sazetidine-A, a new nicotinic cholinergic drug. Anesthesiology. 2008;109:512–9. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181834490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Djuric VJ, Dunn E, Overstreet DH, Dragomir A, Steiner M. Antidepressant effect of ingested nicotine in female rats of Flinders resistant and sensitive lines. Physiol Behav. 1999;67:533–7. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(99)00091-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Furey ML. Replication of scopolamine’s antidepressant efficacy in major depressive disorder: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:432–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulawa SC, Hen R. Recent advances in animal models of chronic antidepressant effects: the novelty-induced hypophagia test. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2005;29:771–83. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SM, Brodkin JD, Lloyd GK, Menzaghi F. Antidepressant-like effects of the subtype-selective nicotinic acetylcholine receptor agonist, SIB-1508Y, in the learned helplessness rat model of depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2000;152:295–303. doi: 10.1007/s002130000531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furey ML, Drevets WC. Antidepressant efficacy of the antimuscarinic drug scopolamine: a randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:1121–9. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.10.1121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatto GJ, Bohme GA, Caldwell WS, Letchworth SR, Traina VM, Obinu MC, Laville M, Reibaud M, Pradier L, Dunbar G, Bencherif M. TC-1734: an orally active neuronal nicotinic acetylcholine receptor modulator with antidepressant, neuroprotective and long-lasting cognitive effects. CNS Drug Rev. 2004;10:147–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1527-3458.2004.tb00010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George TP, Sacco KA, Vessicchio JC, Weinberger AH, Shytle RD. Nicotinic antagonist augmentation of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor-refractory major depressive disorder: a preliminary study. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:340–4. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e318172b49e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey SC, Maddox FN, Luetje CW. Multiple determinants of dihydro-beta-erythroidine sensitivity on rat neuronal nicotinic receptor alpha subunits. J Neurochem. 1996;67:1953–9. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1996.67051953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janowsky DS, el-Yousef MK, Davis JM, Sekerke HJ. A cholinergic-adrenergic hypothesis of mania and depression. Lancet. 1972;2:632–5. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(72)93021-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ke L, Eisenhour CM, Bencherif M, Lukas RJ. Effects of chronic nicotine treatment on expression of diverse nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subtypes. I. Dose- and time-dependent effects of nicotine treatment. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1998;286:825–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenny PJ, File SE, Neal MJ. Evidence for a complex influence of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors on hippocampal serotonin release. J Neurochem. 2000;75:2409–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2000.0752409.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozikowski AP, Eaton JB, Bajjuri KM, Chellappan SK, Chen Y, Karadi S, He R, Caldarone B, Manzano M, Yuen PW, Lukas RJ. Chemistry and pharmacology of nicotinic ligands based on 6-[5-(azetidin-2-ylmethoxy)pyridin-3-yl]hex-5-yn-1-ol (AMOP-H-OH) for possible use in depression. ChemMedChem. 2009;4:1279–91. doi: 10.1002/cmdc.200900079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kroes RA, Burgdorf J, Otto NJ, Panksepp J, Moskal JR. Social defeat, a paradigm of depression in rats that elicits 22-kHz vocalizations, preferentially activates the cholinergic signaling pathway in the periaqueductal gray. Behav Brain Res. 2007;182:290–300. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kudryavtseva NN, Bakshtanovskaya IV, Koryakina LA. Social model of depression in mice of C57BL/6J strain. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 1991;38:315–20. doi: 10.1016/0091-3057(91)90284-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin ED, Rezvani AH, Xiao Y, Slade S, Cauley M, Wells C, Hampton D, Petro A, Rose JE, Brown ML, Paige MA, McDowell BE, Kellar KJ. Sazetidine-A, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic receptor desensitizing agent and partial agonist, reduces nicotine self-administration in rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;332:933–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.109.162073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lippiello PM, Beaver JS, Gatto GJ, James JW, Jordan KG, Traina VM, Xie J, Bencherif M. TC-5214 (S-(+)-mecamylamine): a neuronal nicotinic receptor modulator with antidepressant activity. CNS Neurosci Ther. 2008;14:266–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-5949.2008.00054.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mihalak KB, Carroll FI, Luetje CW. Varenicline is a partial agonist at alpha4beta2 and a full agonist at alpha7 neuronal nicotinic receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:801–5. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.025130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineur YS, Picciotto MR. Nicotine receptors and depression: revisiting and revising the cholinergic hypothesis. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2010.09.004. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mineur YS, Somenzi O, Picciotto MR. Cytisine, a partial agonist of high-affinity nicotinic acetylcholine receptors, has antidepressant-like properties in male C57BL/6J mice. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1256–62. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2007.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NRC. Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. National Research Council; 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overstreet DH. Selective breeding for increased cholinergic function: development of a new animal model of depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1986;21:49–58. doi: 10.1016/0006-3223(86)90007-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paterson NE, Min W, Hackett A, Lowe D, Hanania T, Caldarone B, Ghavami A. The high-affinity nAChR partial agonists varenicline and sazetidine-A exhibit reinforcing properties in rats. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2010 doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2010.07.037. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Addy NA, Mineur YS, Brunzell DH. It is not “either/or”: Activation and desensitization of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors both contribute to behaviors related to nicotine addiction and mood. Prog Neurobiol. 2007;84:329–342. doi: 10.1016/j.pneurobio.2007.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Picciotto MR, Zoli M, Léna C, Bessis A, Lallemand Y, Le Novère N, Vincent P, Merlo-Pich E, Brulet P, Changeux J-P. Abnormal avoidance learning in mice lacking functional high-affinity nicotine receptor in the brain. Nature. 1995;374:65–7. doi: 10.1038/374065a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pucilowski O, Overstreet DH, Rezvani AH, Janowsky DS. Chronic mild stress-induced anhedonia: greater effect in a genetic rat model of depression. Physiol Behav. 1993;54:1215–20. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(93)90351-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabenstein RL, Caldarone BJ, Picciotto MR. The nicotinic antagonist mecamylamine has antidepressant-like effects in wild-type but not beta2- or alpha7-nicotinic acetylcholine receptor subunit knockout mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;189:395–401. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0568-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reitstetter R, Lukas RJ, Gruener R. Dependence of nicotinic acetylcholine receptor recovery from desensitization on the duration of agonist exposure. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:656–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rezvani AH, Slade S, Wells C, Petro A, Lumeng L, Li TK, Xiao Y, Brown ML, Paige MA, McDowell BE, Rose JE, Kellar KJ, Levin ED. Effects of sazetidine-A, a selective alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptor desensitizing agent on alcohol and nicotine self-administration in selectively bred alcohol-preferring (P) rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2010;211:161–74. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1878-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rollema H, Guanowsky V, Mineur YS, Shrikhande A, Coe JW, Seymour PA, Picciotto MR. Varenicline has antidepressant-like activity in the forced swim test and augments sertraline’s effect. Eur J Pharmacol. 2009;605:114–6. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Semba J, Mataki C, Yamada S, Nankai M, Toru M. Antidepressant-like effects of chronic nicotine on learned helplessness paradigm in rats. Biol Psychiatry. 1998;43:389–91. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(97)00477-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharples CG, Kaiser S, Soliakov L, Marks MJ, Collins AC, Washburn M, Wright E, Spencer JA, Gallagher T, Whiteaker P, Wonnacott S. UB-165: a novel nicotinic agonist with subtype selectivity implicates the alpha4beta2* subtype in the modulation of dopamine release from rat striatal synaptosomes. J Neurosci. 2000;20:2783–91. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-08-02783.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shytle RD, Silver AA, Lukas RJ, Newman MB, Sheehan DV, Sanberg PR. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptors as targets for antidepressants. Mol Psychiatry. 2002;7:525–35. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizabi Y, Overstreet DH, Rezvani AH, Louis VA, Clark E, Jr, Janowsky DS, Kling MA. Antidepressant effects of nicotine in an animal model of depression. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 1999;142:193–9. doi: 10.1007/s002130050879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tizabi Y, Rezvani AH, Russell LT, Tyler KY, Overstreet DH. Depressive characteristics of FSL rats: involvement of central nicotinic receptors. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2000;66:73–7. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(00)00236-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turner JR, Castellano LM, Blendy JA. Nicotinic Partial Agonists, Varenicline and Sazetidine-A, have Differential Effects on Affective Behavior. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2010;334:665–672. doi: 10.1124/jpet.110.166280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieyra-Reyes P, Mineur YS, Picciotto MR, Tunez I, Vidaltamayo R, Drucker-Colin R. Antidepressant-like effects of nicotine and transcranial magnetic stimulation in the olfactory bulbectomy rat model of depression. Brain Res Bull. 2008;77:13–8. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2008.05.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Y, Fan H, Musachio JL, Wei ZL, Chellappan SK, Kozikowski AP, Kellar KJ. Sazetidine-A, a novel ligand that desensitizes alpha4beta2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors without activating them. Mol Pharmacol. 2006;70:1454–60. doi: 10.1124/mol.106.027318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zwart R, Carbone AL, Moroni M, Bermudez I, Mogg AJ, Folly EA, Broad LM, Williams AC, Zhang D, Ding C, Heinz BA, Sher E. Sazetidine-A is a potent and selective agonist at native and recombinant alpha 4 beta 2 nicotinic acetylcholine receptors. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;73:1838–43. doi: 10.1124/mol.108.045104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]