Abstract

Liposarcomas are aggressive mesenchymal cancers with poor outcomes that exhibit remarkable histologic diversity, with five recognized subtypes. Currently, the mainstay of therapy for liposarcoma is surgical excision since liposarcomas are often resistant to traditional chemotherapy. In light of the high mortality associated with liposarcoma and the lack of effective systemic therapy, we sought novel genomic alterations driving liposarcomagenesis that might serve as therapeutic targets. ZIC1, a critical transcription factor for neuronal development, is overexpressed in all five subtypes of liposarcoma compared with normal fat and in liposarcoma cell lines compared with adipose-derived stem cells (ASC). Here we show that ZIC1 contributes to the pathogenesis of liposarcoma. ZIC1 knockdown inhibits proliferation, reduces invasion, and induces apoptosis in dedifferentiated and myxoid/round cell liposarcoma cell lines, but not in either ASC or a lung cancer cell line with low ZIC1 expression. ZIC1 knockdown is associated with increased nuclear expression of p27 protein, and the down-regulation of pro-survival target genes: BCL2L13, JunD, Fam57A, and EIF3M. Our results demonstrate that ZIC1 expression is essential for liposarcomagenesis and that targeting ZIC1 or its downstream targets may lead to novel therapy for liposarcoma.

Keywords: Liposarcoma, oncogenesis, ZIC1

Introduction

Liposarcoma is the most common type of soft tissue sarcoma, accounting for at least 20% of adult sarcomas (1). Based on morphologic features and cytogenetic aberrations, liposarcomas are classified into three biological types encompassing five subtypes: (1) well-differentiated/dedifferentiated, (2) myxoid/round cell (RC), and (3) pleomorphic. The histologic subtype of liposarcoma remains the most important prognostic factor for survival, while tumor location, size, and completeness of resection improve outcome prediction for the individual patient (2, 3). Although diagnosis and clinical management have improved over the past decade, 40% of newly diagnosed patients will eventually die of the disease and new treatments are urgently needed for patients (roughly 1,250 in the US each year) who will die from inoperable liposarcoma. Our group has been conducting a genome-wide molecular genetic analysis of liposarcoma. The goal is to discover the ‘driver’ genetic alterations necessary for liposarcomagenesis, with the expectation that identifying such genes will lead to the discovery of novel therapeutic targets, improve diagnosis of liposarcoma subtypes, and improve outcome prediction for the individual patient.

ZIC1, one of five ZIC-family genes (4), is a transcription factor notable for involvement in multiple developmental processes, including neurogenesis, myogenesis, and left-right axis establishment (5). In the normal adult, ZIC1 expression has been detected only in neural tissues, typically restricted to the cerebellum. The coordinated expression of ZIC1 during neural tube development is required for proper cerebellar development (6). Heterozygous ZIC1 deletion is associated with Dandy-Walker malformation (7).

All five ZIC-family members share five highly conserved tandem repeats known as C2H2 zinc finger motifs. Similar zinc finger domains have been described in the Gli family proteins, which can interact with ZIC-family members in both antagonistic and synergistic fashions (8). Surprisingly, given its importance in cerebellar development, little is known about how ZIC1 is regulated or how it controls the expression of downstream targets. ZIC1 induces expression of several wnt genes in Xenopus (9) and strongly activates the human apolipoprotein E gene (10). ZIC1 expression is regulated by bone morphogenetic protein (BMP)-related signals (11, 12).

In neurons, aberrant regulation of ZIC1 has a well-defined oncogenic role. ZIC1 is commonly expressed in medulloblastoma (13). ZIC1 overexpression in mice decreases neuronal differentiation and expands neural progenitors (6), functions that could underlie a role in tumor initiation and progression. Also, ZIC1 overexpression in chick neural tubes blocks differentiation (14), and when ZIC1 was aberrantly expressed in the ventral spinal cord (where it is normally absent), the cells failed to express markers normally seen on differentiated neuronal cells. However, in humans, aberrant ZIC1 expression is also seen in other solid tumors (15), including endometrial cancer (16) and desmoid tumors (15). However, neither the importance of ZIC1 nor its oncogenic role in these diseases has been clearly elucidated.

Here, we show that not only is ZIC1 overexpressed in all five liposarcoma subtypes, but also in additional genetically complex sarcoma types. We further demonstrate that the proliferation and survival of liposarcoma cell lines depends on ZIC1 overexpression. We also show that the lethal effects of ZIC1 knockdown are selective for liposarcoma cells, but not for cells that do not overexpress ZIC1. Furthermore, we demonstrate that the anti-proliferative effects of ZIC1 knockdown in liposarcoma cells may be, in part, due to increased expression and activation of p27 protein.

Materials and Methods

ZIC1 Gene Expression Profiling

Affymetrix U133A microarrays were used to compile gene expression profiles to compare patients’ liposarcomas [dedifferentiated (n=51), well-differentiated (n=51), myxoid (n=14), myxoid/RC (n=12), pleomorphic (n=22)] with subcutaneous or retroperitoneal normal fat (n=13). This comparison was expanded to include other soft tissue sarcomas, including leiomyosarcoma (n=23), malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH) (n=5), gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GIST) (n=99), and myxofibrosarcoma (n=36). We then combined our microarray data with data from the Novartis Gene Expression Atlas (http:// biogps.gnf.org) and various GEO sets (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo) to determine the relative expression of ZIC1 in soft tissue sarcoma and normal fat to other human tissues, including central nervous system tissues, and to epithelial-derived cancers, such as colorectal and breast cancers (17). All data were analyzed with Bioconductor packages for the R statistical programming system. Quantitation and normalization were done with the gcRMA package, and differential gene expression was computed with the LIMMA package. The Benjamini and Hochberg False Discovery Rate (FDR) method was used to correct for multiple testing.

ZIC1 Immunofluorescence on Tissue Microarray (TMA)

TMA slides were deparaffinized with xylene, followed by antigen retrieval by microwaving in sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) for 5 to 10 minutes. Samples were permeabilized with 10% triton/1X phosphate-buffered saline for 20 minutes. Rabbit anti-human/mouse Zic-1 (ab72694, Abcam, Cambridge, MA) was applied at 1:50 dilution, and incubated at room temperature for 4 hours, then goat-anti-rabbit-Alexa-594 (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA), was added at 5μg/ml and incubated at room temperature for 1.5 hours. The cells were then stained with DAPI (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), and mounted with vectorshield (Vector, Burlingame, CA). The results were viewed under Zeiss widefield microscopy and the images analyzed with Axiovision 4.6.

Cell Culture and Treatment

DDLS8817, LPS141, and ML2308 liposarcoma cell lines were established from dedifferentiated and myxoid/RC liposarcoma samples obtained from patients who signed informed consent. The dedifferentiated (DDLS8817 and LPS141) cell lines were confirmed by cytogenetic analysis and by DNA copy number arrays (Agilent 244K) to harbor 12q amplification. The myxoid/RC cell line (ML2308) was found to contain the TLS-CHOP fusion transcript variant type 8-2 by RT-PCR. Primary human adipocyte-derived stem cells (ASCs) were isolated as described (18) using subcutaneous fat tissue samples from consenting patients. Cell lines were maintained in DMEM HG:F12 supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Invitrogen). The lung adenocarcinoma cell line, A549 (ATCC, Manassas, VA) was maintained in F12K with 1.5g/L sodium bicarbonate and 10% FBS.

Quantitative Real-Time Reverse Transcription PCR

RNA was extracted from macro-dissected cryomolds of tissue samples and reverse transcription was performed as described(19) to detect ZIC1 (Hs00602749_m1) and 18s rRNA (Hs99999901_s1). Relative expression of ZIC1 was calculated by normalizing its expression to that of 18s rRNA. Statistical significance for all RT-PCR reactions was determined as described (20).

Immunofluorescence for ZIC1 in Cell Lines

Cells were seeded and grown overnight on chamber slides to approximately 75% confluence and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde. Cells were permeabilized, blocked, and incubated overnight with anti-ZIC1 (ab72694, Abcam) or anti-p27 (sc-528, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at a 1:100 dilution in 2% BSA/1XPBS in a humidified chamber at 4°C. Slides were developed with goat anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (A11034, Invitrogen) at 1:1000 dilution in 2% BSA/1XPBS for 1.5 hours in a humidified chamber then mounted with DAPI medium (sc-24941, Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Fluorescent images were captured using an Olympus IX71 microscope.

shRNA Infection

Four short-hairpin RNAs (shRNAs) in the pLKO.1 vector (Sigma-Aldrich, USA) were tested. Greatest knockdown of ZIC1 gene expression was achieved by ZIC1 Z1 “CGAGCGACAAGCCCTATCTTT” and ZIC1 Z4 “GCCATATTTGACTCTGAGAAA”. The negative control was a scramble (Scr) sequence not targeting any known human genes, “CAACAAGATGAAGAGCACCAA”. These constructs were produced in a lentivirus system by the transient cotransfection of 293T cells (ATCC) using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) with 10 µg of lentiviral plasmid, 9 µg of packaging plasmid psPAX2, and 1 µg of envelope plasmid pMD2.G. Viral supernatants (in HG-DMEM + 10% iFBS + 1.1g/100mL BSA + 1x Pen/Strep) were collected at 48, 72, and 96 h after transfection, pooled, and concentrated by centrifugation using an Amicon Ultra-15 100K cutoff filter device (Millipore, USA). Cells infected with lentivirus were selected for with 1 µg/ml puromycin. Knockdown of ZIC1 gene expression was confirmed by RT-PCR and IF.

Proliferation Assays

DNA content was estimated and data analyzed as described(19), except cells were plated in 96-well plates at a density of 103 cells per well and collected for four days.

BrdU Uptake

Cells (3 ×105) were plated in 10-cm culture plates. Adherent cells were incubated with 10uM of bromodeoxyuridine (Sigma-Aldrich) and fixed and analyzed using standard methods.

Annexin V/7-AAD Apoptosis Assay

Apoptosis was evaluated as described (19).

Cleaved Caspase3 Immunohistochemistry

Cleaved Caspase 3 was detected by immunohistochemistry using standard methods.

Matrigel Invasion Assay

The Matrigel invasion membrane (BD BioCoat™ Matrigel™ Invasion Chamber, BD Biosciences) was rehydrated, and 2.5×104 cells were added to a control or Matrigel invasion chamber in triplicate and placed in a humidified incubator for 22 hours. Non-invading cells were removed, and the membranes containing the invading cells were stained using the Diff-Quik™ staining kit (Dade Behring, U.S.). Cells were counted in three separate fields at 40X magnification and percent invasion was calculated as invasion through the Matrigel membrane relative to migration through the control membrane.

Immunoblot

Cell lysates containing 30 µg of protein were resolved by SDS-PAGE, transferred onto Immuno-Blot polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA), and probed with antibody for p27 (sc-528, Santa Cruz Biotechnology).

Microarray Analysis of ZIC1 shRNA Infected Cells

DDLS8817 and LPS141 cells were infected with ZIC1 Z1 and Scr constructs in triplicate. RNA was isolated and following confirmation of ZIC1 knockdown was submitted for Illumina gene expression analysis (Illumina, Inc., San Diego, CA).

Results

ZIC1 expression in diverse human tissue types and soft tissue sarcomas

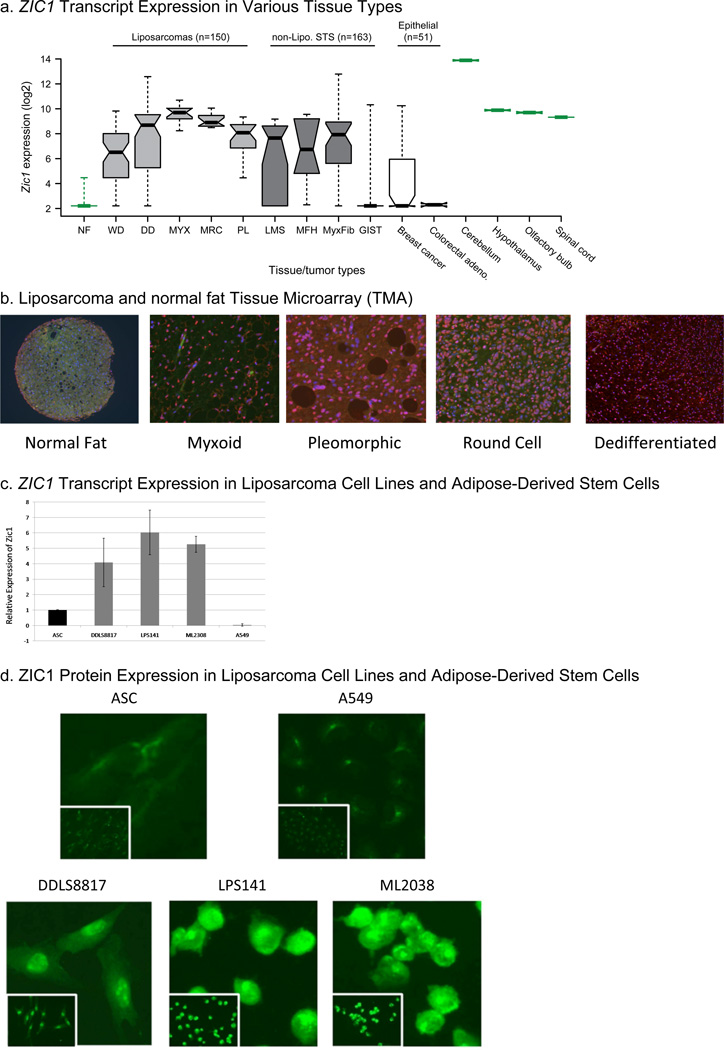

We determined ZIC1 expression levels from global gene expression analysis of normal fat and of 364 human tumors, including all five liposarcoma subtypes and other soft tissue sarcoma types. Well-differentiated, dedifferentiated, myxoid, RC, and pleomorphic liposarcoma tissue samples had 10.8- to 130.5-fold greater mean ZIC1 expression than did corresponding normal fat samples (FDR<2.7E-05 in all pair-wise comparisons) (Figure 1A). Leiomyosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma (MFH), and myxofibrosarcomas also demonstrated 12.2- to 24.5- fold increase in ZIC1 expression compared with normal fat (FDR<0.005). GIST, however, did not have an increase (fold change 1.2; FDR=0.80). When compared to publically available gene expression data for other tissue types, the fold-change of ZIC1 expression in the CNS compared with normal fat ranged from 110.0 (FDR=0.0004) in the spinal cord to 2598 (FDR=4.8E-10) in the cerebellum. Thus, for some liposarcoma subtypes, ZIC1 expression appears to be restored to the levels observed in non-cerebellar CNS tissues (Figure 1A). Unlike liposarcomas, epithelial-derived breast and colorectal cancers did not demonstrate significantly increased ZIC1 expression compared with normal fat (fold changes of 2.4 and −1.19, respectively [FDR>0.1]) (Figure 1a).

Figure 1.

(a) Box plot of ZIC1 expression as determined from Affymetrix U133A chip data in combination with data from the Novartis Gene Expression Atlas and various GEO sets. The expression data come from 21 normal tissue samples and 364 human tumors samples: 150 liposarcoma, 163 non-liposarcoma soft tissue sarcoma, and 51 epithelial tumors. The whiskers (dotted lines) show the data extremes. The boxes represent the interquartile range (from 25th to 75th percentile of the expression), with the dark bars representing the medians. The width of the notches approximate the 95% confidence interval for the difference in two medians. NF, normal fat; WD, well-differentiated; DD, dedifferentiated; MYX, myxoid; MRC, myxoid/RC; PL, pleomorphic; LMS, leiomyosarcoma; MyxFib, myxofibrosarcoma. (b) ZIC1 immunofluorescence on liposarcoma TMA. The images shown are representative of the ZIC1 staining pattern in all samples of that tissue type studied. (c) ZIC1 transcripts quantified by RT-PCR in ASCs, dedifferentiated liposarcoma cell lines (DDLS8817 and LPS141), a myxoid/RC cell line (ML2308), and a lung cancer cell line (A549). (d) Immunofluorescence for ZIC1 in the same cell lines.

To determine whether ZIC1 overexpression in these diverse sarcoma subtypes resulted from genomic amplification, we performed high-resolution DNA copy number profiling on 241 tumors across these subtypes with both Affymetrix 250K SNP arrays and Agilent 244K aCGH arrays. We found little evidence of recurrent, focal, or high-level amplification of the ZIC1 locus (3q24). Additionally, we sequenced the coding exons and adjacent splice junctions of ZIC1 in 51 dedifferentiated, 4 well-differentiated, 18 myxoid, and 23 RC liposarcoma samples and just found three synonymous mutations, which are likely SNPs.

ZIC1 Is Overexpressed in All Liposarcoma Sub-Types

To validate the overexpression of ZIC1 at the protein level in the five liposarcoma subtypes, we performed immunofluorescence for ZIC1 on a liposarcoma TMA. The TMA contained 10 to 15 representative tissue samples of each liposarcoma subtype. The fluorescent nuclear signal for ZIC1 was much stronger in all liposarcoma subtypes than in the normal fat tissue samples (Figure 1b). Therefore, both ZIC1 transcript and protein expression are greater in liposarcomas than in normal fat.

ZIC1 Is Overexpressed in Liposarcoma Cell Lines

To establish a laboratory model to study ZIC1 overexpression, we compared the relative expression of ZIC1 by RT-PCR in two dedifferentiated cell lines (DDLS8817 and LPS141), a myxoid/RC cell line (ML2308), a lung adenocarcinoma cell line (A549), and adipocyte-derived stem cells (ASCs) (Figure 1c). ZIC1 expression, relative to expression in ASCs, was 4.1–6.0 times higher (P<0.05, determined as described (20)) in the liposarcoma cell lines and 0.03 times as high in A549 cells (P<0.05). We next performed immunofluorescence for ZIC1 in the same cell lines. This confirmed that the ZIC1 protein expression was higher in the liposarcoma cell lines than in ASCs and A549 cells (Figure 1d), consistent with the U133A transcriptional results.

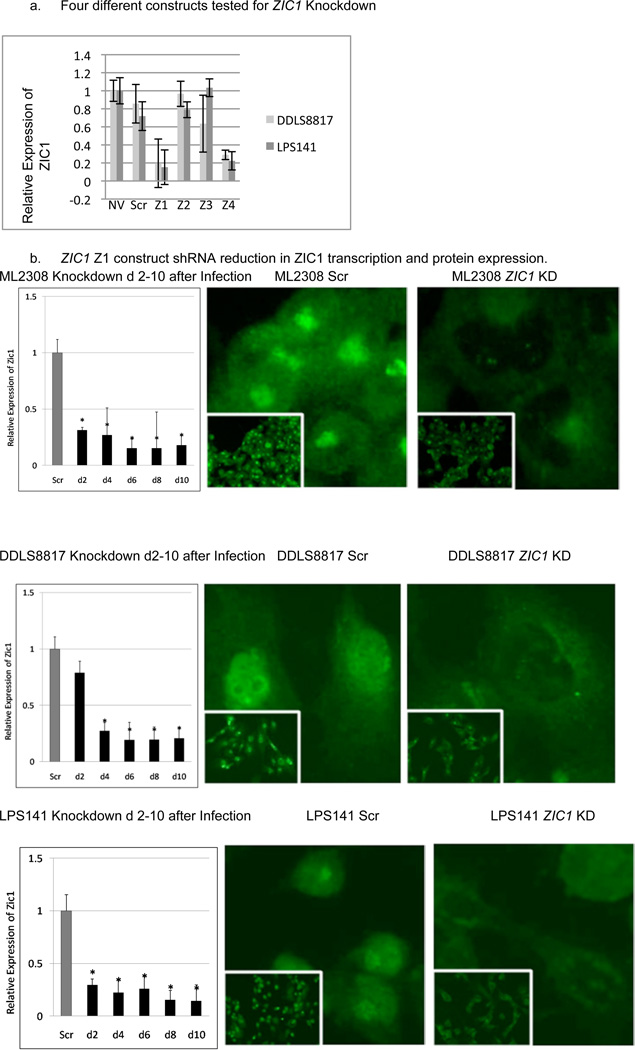

shRNA Knockdown of ZIC1

To study the dependence of liposarcoma cell survival on ZIC1 expression, we reduced its expression using an shRNA lentiviral system. We initially tested four different constructs and determined by RT-PCR that two constructs, labeled Z1 and Z4, were most effective in reducing ZIC1 mRNA levels (Figure 2a). This paper describes the results using construct Z1, but all functional studies were also conducted with Z4, with similar results (available on request). Z1 knocked down ZIC1 mRNA levels in all liposarcoma cell lines to approximately 30% of levels seen in control cells transduced with scramble shRNA by four days postinfection (P<0.05) (Figure 2b). ZIC1 immunofluorescence 8 days postinfection with the Z1 lentivirus indicated less nuclear signal than in the scramble controls in the liposarcoma cell lines. Knockdown with Z1 resulted in similarly reduced ZIC1 expression in ASCs and in the A549 lung cancer cell line.

Figure 2.

(a) Extent of knockdown of ZIC1 transcription with four different ZIC1 constructs, compared with no-virus (NV) and scramble (Scr) controls. (b). ZIC1 immunofluorescence 8 days postinfection in the ZIC1 knockdown liposarcoma cells.

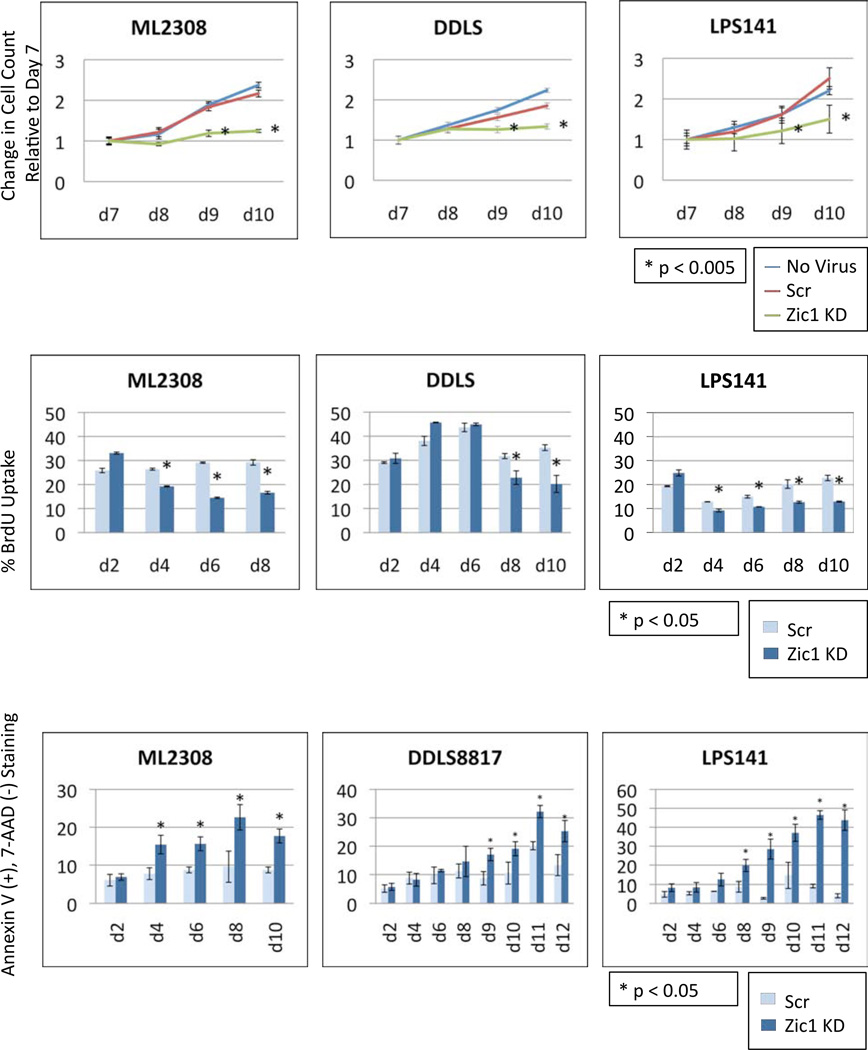

ZIC1 Knockdown Inhibits Proliferation of Liposarcoma Cells

Beginning seven days after lentiviral infection, a CyQuant DNA quantification assay (Figure 3a) showed a reduction in cell proliferation in the ZIC1 knockdown liposarcoma cells, compared with the scramble and no-virus controls. Ten days after knockdown, the number of ZIC1-knockdown cells relative to scramble controls was reduced 50% (P<0.001), 20% (P<0.001) and 40% (P<0.001) in ML2308, DDLS8817, and LPS141 cells, respectively. Thus, ZIC1 knockdown significantly reduced cell proliferation in all 3 liposarcoma cell lines.

Figure 3.

(a) Effects of ZIC1 knockdown on proliferation of liposarcoma cells. Cell proliferation postinfection with Z1 knockdown construct or Scr control and in no virus control was assessed by a DNA quantitation assay (CyQuant). Statistical differences between the ZIC1 knockdowns and the Scr control cells were analyzed using the 2-tailed unpaired t-test. (b) BrdU incorporation assays in liposarcoma cell lines postinfection with Z1 knockdown or Scr control constructs. The histograms show the percentage of cells actively synthesizing their DNA in S Phase. This experiment for ML2308 cells was stopped at day 8 because not enough viable cells remained at day 10. Statistical significance was assessed using the two-tailed unpaired t-test. (c) Early apoptosis, measured by Annexin V and 7-AAD staining.

To confirm the reduced proliferation of liposarcoma cells following ZIC1 knockdown, we determined the percentage of liposarcoma cells that incorporated BrdU, indicating active DNA replication. ZIC1 knockdowns were compared with scramble controls starting 2 days postinfection (Figure 3b). In both ML2308 and LPS141, BrdU uptake was reduced 30% beginning 4 days postinfection, and this peaked on day 6 in ML2308 and on day 10 in LPS141 with a 50% (P<0.001) reduction in the BrdU uptake in the ZIC1 knockdowns versus scramble controls. The results in DDLS8817 were similar, but the decrease in BrdU uptake began 8 days postinfection and peaked at 10 days with a 28% (P<0.05) and 43% (P<0.05) reduction, respectively. In each liposarcoma cell line studied, the reduction in BrdU uptake in ZIC1 knockdown compared with scramble controls was significant. Thus, ZIC1 knockdown resulted in reduced DNA replication and thus reduced proliferation in liposarcoma cells.

ZIC1 Knockdown Induces Apoptosis in Liposarcoma Cells

We measured apoptosis with Annexin V and 7-AAD staining and found the myxoid/RC cell line (ML2308) showed the earliest effects of decreased ZIC1 transcription with a 2.0-fold increase in Annexin V(+), 7-AAD(−) staining in the ZIC1 knockdowns compared with the scramble controls measured 6 days postinfection (P<0.001) (Figure 3c). This effect peaked at day 8 with a 2.3-fold increase in Annexin V(+), 7-AAD(−) staining (p<0.01). For DDLS8817, maximum Annexin V(+), 7-AAD(−) staining occurred 9 days postinfection, with a 1.9-fold increase in staining in the ZIC1 knockdowns compared with the scramble controls (P<0.001). In LPS141, Annexin V staining plateaued on day 12 with a 10.9-fold increase in Annexin V(+),7-AAD(−) staining (P<0.001). Thus, depending on the liposarcoma cell line, ZIC1 knockdown induced a 2- to 11-fold increase in apoptosis compared with scramble controls, which peaked 8-12 days postinfection.

To confirm the Annexin V/7-AAD apoptosis results, immunohistochemistry for cleaved caspase 3 was performed eight days after lentivirus infection. ZIC1 knockdown increased cleaved caspase 3 staining: 3.0 ± 0.3-fold in ML2308, 2.0 ± 0.7-fold in DDLS8817, and 2.4 ± 0.8-fold in LPS141 compared to the Scr controls (Supplemental Figure 2).

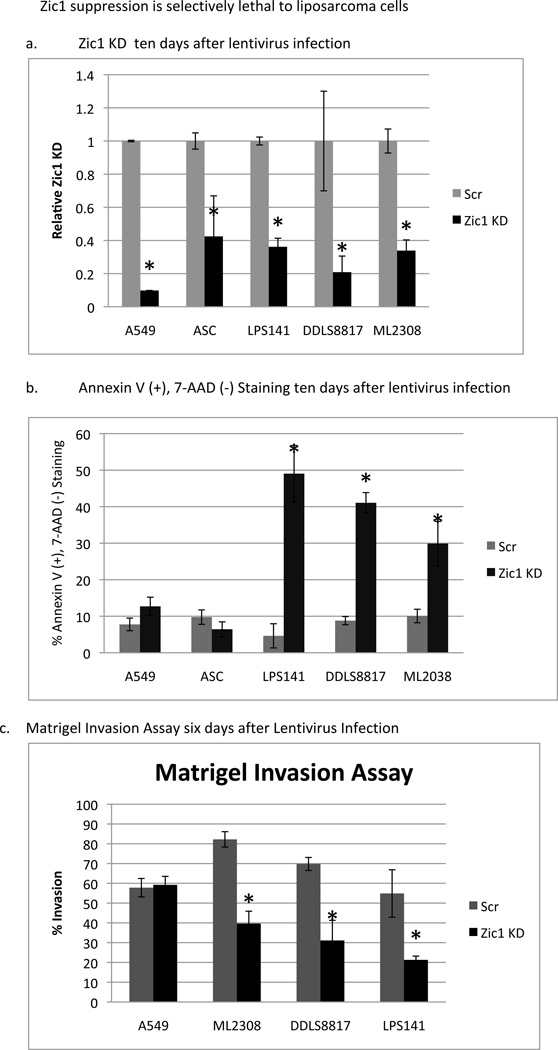

To determine if the induction of apoptosis following ZIC1 knockdown was specific to liposarcoma cells that overexpressed ZIC1, the same shRNA lentiviral system was used to knock down ZIC1 expression in ASCs and in A549 lung cancer cells, both of which have low levels of ZIC1 expression (Figure 4a). Ten days postinfection, Annexin V(+), 7-AAD(−) staining in these two cell types was compared with that in the three liposarcoma cells lines (Figure 4b). In the liposarcoma cell lines, the ZIC1 knockdowns resulted in a 3- to 11-fold increase in apoptosis compared with the scramble controls (P<0.05). In contrast, in the non-transformed ASCs and in the non-ZIC1 A549 cell line, apoptosis was not significantly increased in the ZIC1 knockdowns compared with controls. These results suggest that ZIC1 knockdown is specifically lethal to liposarcoma cells that overexpress ZIC1.

Figure 4.

Selective effects of ZIC1 knockdown on apoptosis and invasion of liposarcoma cells compared to ASCs and A549 lung cancer cells. (a) Verification of ZIC1 knockdown with the Z1 shRNA compared to Scr control by RT-PCR. (b) Annexin V and 7-AAD staining to measure apoptosis in the ZIC1 knockdown cells compared with Scr controls. (c) Effects of ZIC1 knockdown on the invasiveness of liposarcoma and lung cancer cells. At 6 days postinfection, cells were seeded into Matrigel invasion chambers, and invasion was assessed 22 hours later. Asterisks mark statistically significant differences (P<0.05) between ZIC1 knockdown and Scr control.

ZIC1 Knockdown Inhibits Liposarcoma Cell Invasion

To determine whether ZIC1 overexpression contributes to the invasiveness of liposarcoma cells, we seeded ZIC1-knockdown, scramble control liposarcoma, and A549 cells six days after knockdown into Matrigel invasion chambers. Twenty-two hours after seeding, ML2308, DDLS8817, and LPS141 ZIC1 knockdown cells demonstrated 21–40% invasion, which was lower than in scramble controls (55–82% invasion, respectively; P<0.01; Figure 4c). Thus, the percentage of invading cells was decreased after reducing ZIC1 expression in all three liposarcoma cell lines. There was no significant difference in invasion between the scramble and ZIC1-knockdown A549 cells.

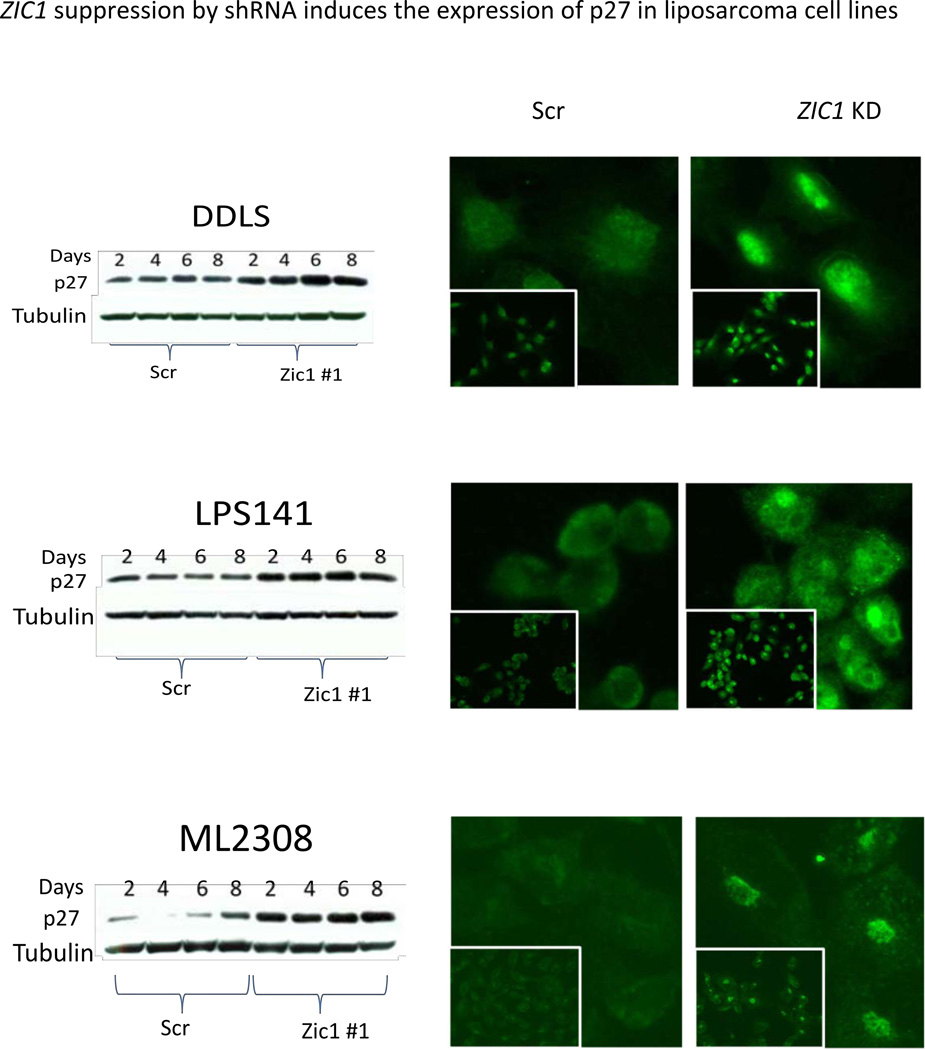

Knockdown of ZIC1 Is Associated with Increased in p27 Expression and Activation

Previous studies indicated that ZIC1-mutant mice have increased p27 protein expression, and that ZIC1 overexpression increases cell proliferation, inhibits neuronal differentiation, and decreases p27 expression in the cerebellum (6). Based on these findings, we postulated that the functional effects of ZIC1 overexpression in liposarcoma, driving proliferation and inhibiting differentiation, were partially mediated through p27 downregulation. To determine the effects of ZIC1 knockdown on p27 protein expression, we performed immunoblots of p27 for liposarcoma cells following ZIC1 knockdown and compared these with scramble controls. All three liposarcoma cell lines with ZIC1 knockdown showed an increase in p27 protein expression by as early as 2 days postinfection compared with scramble controls (Figure 5). The immunoblot results were validated by immunofluorescence, which identified not only an increase in p27 protein expression, but also increased nuclear localization of p27 in the ZIC1 knockdowns compared with controls in the three liposarcoma cell lines (Figure 5). These results suggest that ZIC1 knockdown is associated with increased levels of p27 in the nucleus, where it can act to inhibit cell proliferation.

Figure 5.

Left, immunoblots for p27 protein expression in ZIC1 knockdown and Scr control cells two to eight days after lentivirus infection. Right, p27 immunofluorescence.

Target Genes of ZIC1 Knockdown in Dedifferentiated Liposarcoma Cell Lines

To further address the pro-survival function of ZIC1, we investigated which genes were differentially expressed in a manner specific to ZIC1 knockdown. We performed expression array analysis using both LPS141- and DDLS8817-ZIC1 knockdown and compared the results with scramble controls at four and eight days following shRNA transfection, the time when apoptotic indices began to rise. Several genes were 2- to 4-fold down-regulated in both liposarcoma cell lines compared to scramble controls (Table 1 and Supplementary Table 1A-D) and were therefore considered putative ZIC1 target genes. For four of these genes that are novel as putative ZIC1 targets, we confirmed ZIC1-dependent expression by RT-PCR (Supplemental Figure 1). Both the JunD proto-oncogene and BCL2L13 may protect cells from apoptosis depending on the cellular context. FAM57A, a RAF/PI3K/AKT pathway activator, and EIF3M, an essential gene required for global protein synthesis, are known drivers of proliferation and survival. Thus, all four of these validated putative ZIC1 target genes are significantly reduced with ZIC1 knockdown in liposarcoma cell lines and are likely to mediate the reduced proliferation and enhanced apoptosis observed following ZIC1 knockdown.

Table 1. Potential Pro-Survival Target Genes of ZIC1.

Expression fold-change in potential pro-survival ZIC1 target genes discovered by expression array analysis of ZIC1 knockdown compared to scramble control dedifferentiated liposarcoma cells (DDLS8817 and LS141) at four and eight days following shRNA transfection.

| ZIC1 Target Gene | Expression fold-change in DDLS days 4 and 8, respectively, after ZIC1 knockdown | Expression fold-change in LPS141 days 4 and 8, respectively, after ZIC1 knockdown |

|---|---|---|

| BCL2L13 | −4.0; −4.4 | −2.0; NS |

| JunD | −2.4; −2.3 | −2.1; −2.1 |

| Fam57A (CT120) | −2.6; −2.2 | −2.5; −2.4 |

| EIF3M | −3.1; −3.1 | −2.7; −2.7 |

Discussion

Genetically, liposarcomas fall into two broad categories. Those with simple near-diploid karyotypes bear few chromosomal rearrangements, such as translocations in myxoid/round-cell liposarcoma [t(12;16)(q13;p11), t(12;22)(q13;q12)]. In contrast, liposarcomas with complex karyotypes, including well-differentiated/dedifferentiated and pleomorphic liposarcoma, have varying degrees of chromosomal instability (21). Most of these complex liposarcoma types have frequent abnormalities in the Rb, p53, and specific growth-factor signaling pathways, including amplification of the 12q14 chromosome region encompassing the MDM2 and CDK4 loci in dedifferentiated liposarcoma (22), but many of the key driver genes critical to liposarcomagenesis remain to be discovered. Here we show that ZIC1 is significantly overexpressed in all 5 liposarcoma subtypes compared with normal fat and that both genetically simple and complex liposarcoma types depend on ZIC1 overexpression for proliferation, invasion, and survival. We also discovered ZIC1 overexpression in other types of soft tissue sarcoma, including leiomyosarcoma, MFH, and myxofibrosarcoma. GIST is the only sarcoma type examined that did not overexpress ZIC1. As GIST tumorigenesis is primarily characterized by mutations in c-KIT and PDGFRA, lesions not characteristic of ZIC1-overexpressing subtypes, it is likely the pathogenesis of the latter is distinct in the requirement for ZIC1 overexpression (23–25). The overexpression of ZIC1 in eight of nine soft tissue sarcoma and liposarcoma subtypes studied here make this gene a promising biomarker associated with mesenchymal transformation, and a potential selective therapeutic target due to the low or absent ZIC1 expression in adult tissues outside of the CNS.

In the CNS ZIC1 inhibits premature neuronal differentiation and increases cell proliferation in neural development. However, the underlying molecular actions of ZIC1 protein remain a mystery. Some studies have raised the possibility that ZIC proteins can act as transcriptional cofactors and modulate the hedgehog-signaling pathway and that ZIC proteins inhibit neuronal differentiation by activating Notch signals (5). While the role of ZIC1 in the CNS has been investigated, the functional effects of ZIC1 overexpression in soft tissue sarcoma have, until now, not been examined.

Three different liposarcoma cell lines were used to model the potential proliferative role of ZIC1 overexpression in the liposarcoma human tumors. The functional effects of ZIC1 knockdown were consistent: decreases in proliferation, BrdU uptake, and Matrigel invasion and increase in apoptosis. Specificity of these responses are supported by ZIC1 knockdown having no effect on apoptosis or invasion in normal ASCs, which are neither immortal nor transformed, or in the A549 cell line, which does not to overexpress ZIC1 by RT-PCR and immunofluorescence. Thus, the overexpression of ZIC1 is essential for survival and proliferation in these liposarcoma cell lines and not in the normal progenitors or in proliferating cells in general.

The majority of ZIC1 studies have investigated its role in the CNS, and as previously mentioned, murine ZIC1 mutants were shown to express elevated p27 and Wnt7a, but decreased cyclin D1 (6). While we did not observe a correlation between ZIC1 expression and Wnt7A and/or Cyclin D1, we did demonstrate a relationship between ZIC1 knockdown and an increase in p27 protein expression in vitro. As previously reported, increases in p27 expression have been shown to reduce proliferation (26), reduce BrdU uptake(27), increase Annexin V staining (28), and decrease Matrigel invasion (29). Immunoblots demonstrated an increase in p27 protein expression in the ZIC1 knockdowns as early as 2 days after lentivirus infection and reached its maximal level 6 days postinfection. In addition, immunofluorescence showed that ZIC1 knockdown also appeared to activate p27 by its nuclear localization. Thus, the increase in p27 expression in all 3 liposarcoma cell lines following ZIC1 knockdown explains many of the observed early functional effects on cell proliferation and invasion. However, the observed maximal increases in p27 by 6 days does not account for marked increase in cell death observed following 8 days of ZIC1 knockdown suggesting that additional ZIC1 target genes may be mediating liposarcoma cell survival.

To discover putative ZIC1 target genes we then performed expression array analysis 4 and 8 days following ZIC1 knockdown and found that BCL2L13 was 4-fold and 2-fold downregulated in DDLS and LPS141, respectively. BCL2L13 shows overall structural homology to the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 family of proteins, but contains a C-terminal membrane anchor region that is preceded by a unique 250-amino acid insertion containing 2 tandem repeats. BCL2L13 induces significant apoptosis with caspase-3 activation when transfected into 293T cells (30). BCL2L13 overexpression has been associated with L-asparaginase resistance and unfavorable clinical outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia (31). This finding suggests that BCL2L13 may have a different apoptotic role in primary leukemic cells and in our dedifferentiated liposarcoma cell lines compared with the 293T cell lines, initially used to describe its apoptotic role. Four days following ZIC1 knockdown JunD was 2.4-fold and 2.1-fold downregulated in DDLS8817 and LPS141, respectively. The JunD proto-oncogene is a functional component of the AP1 transcription factor complex and exhibits a cell-dependent role in apoptosis. For example, JunD expression prevents cell death in adult mouse heart cells (32) and in UV/H2O2-stressed mouse embryonic fibroblasts (33). JunD has been proposed to protect cells from p53-dependent senescence and apoptosis (34) and its downregulation upon ZIC1 knockdown may account for the induction of apoptosis in our liposarcoma cell lines. Fam57A (CT120), a membrane-associated gene important for amino acid transport (35), was found to be 2.6- and 2.5-fold downregulated in DDLS8817 and LPS141, respectively. CT120 has been implicated in lung carcinogenesis and its ectopic expression in NIH3T3 cells has been associated with Raf/MEK/Erk and PI3K/Akt signaling pathways driving cell proliferation, cell survival, and anti-apoptotic pathways (36). EIF3M, eukaryotic initiation factor 3 subunit M, is an essential gene for global cellular protein synthesis and polysome formation and appears to be associated with the bulk of cellular mRNAs (37). The ectopic expression of the other EIF3 subunits, −3a, −3b, −3c, −3h, or −3i in stably transfected NIH3T3 cells has been shown to induce oncogenic transformation, enhance proliferation, and attenuate apoptosis (38). These findings suggest that the 3-fold downregulation of EIF3M following ZIC1 knockdown would inhibit protein synthesis and proliferation in liposarcoma cells.

We present here evidence that ZIC1 expression is necessary for liposarcoma proliferation, invasion, and survival and have identified several ZIC1 target genes that may mediate its functional effects. The overexpression of ZIC1 in both liposarcomas and, more broadly, other soft tissue sarcoma types and not in normal adult tissues outside of the CNS, makes this gene or its downstream targets a promising therapeutic target in these tumor types.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the members of the MSKCC Genomics Core Laboratory and N.H. Moraco for clinical data support. This work was supported in part by The Soft Tissue Sarcoma Program Project (P01 CA047179, S.S. and C.S.), The Kristen Ann Carr Fund, and a generous donation from Richard Hanlon.

References

- 1.Fletcher C, Unni K, Mertens F, editors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer Press; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dalal KM, Kattan MW, Antonescu CR, Brennan MF, Singer S. Subtype specific prognostic nomogram for patients with primary liposarcoma of the retroperitoneum, extremity, or trunk. Ann Surg. 2006;244:381–391. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000234795.98607.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Singer S, Antonescu CR, Riedel E, Brennan MF. Histologic subtype and margin of resection predict pattern of recurrence and survival for retroperitoneal liposarcoma. Ann Surg. 2003;238:358–370. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000086542.11899.38. discussion 70-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aruga J, Yokota N, Hashimoto M, Furuichi T, Fukuda M, Mikoshiba K. A novel zinc finger protein, zic, is involved in neurogenesis, especially in the cell lineage of cerebellar granule cells. J Neurochem. 1994;63:1880–1890. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1994.63051880.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aruga J. The role of Zic genes in neural development. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;26:205–221. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aruga J, Inoue T, Hoshino J, Mikoshiba K. Zic2 controls cerebellar development in cooperation with Zic1. J Neurosci. 2002;22:218–225. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.22-01-00218.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grinberg I, Northrup H, Ardinger H, Prasad C, Dobyns WB, Millen KJ. Heterozygous deletion of the linked genes ZIC1 and ZIC4 is involved in Dandy-Walker malformation. Nat Genet. 2004;36:1053–1055. doi: 10.1038/ng1420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Koyabu Y, Nakata K, Mizugishi K, Aruga J, Mikoshiba K. Physical and functional interactions between Zic and Gli proteins. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6889–6892. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C000773200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Merzdorf CS, Sive HL. The zic1 gene is an activator of Wnt signaling. Int J Dev Biol. 2006;50:611–617. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.052110cm. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Salero E, Perez-Sen R, Aruga J, Gimenez C, Zafra F. Transcription factors Zic1 and Zic2 bind and transactivate the apolipoprotein E gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:1881–1888. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M007008200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rohr KB, Schulte-Merker S, Tautz D. Zebrafish zic1 expression in brain and somites is affected by BMP and hedgehog signalling. Mech Dev. 1999;85:147–159. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(99)00044-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grinblat Y, Sive H. zic Gene expression marks anteroposterior pattern in the presumptive neurectoderm of the zebrafish gastrula. Dev Dyn. 2001;222:688–693. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.1221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Michiels EM, Oussoren E, Van Groenigen M, et al. Genes differentially expressed in medulloblastoma and fetal brain. Physiol Genomics. 1999;1:83–91. doi: 10.1152/physiolgenomics.1999.1.2.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ebert PJ, Timmer JR, Nakada Y, et al. Zic1 represses Math1 expression via interactions with the Math1 enhancer and modulation of Math1 autoregulation. Development. 2003;130:1949–1959. doi: 10.1242/dev.00419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pourebrahim R, Van Dam K, Bauters M, et al. ZIC1 gene expression is controlled by DNA and histone methylation in mesenchymal proliferations. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:5122–5126. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.09.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wong YF, Cheung TH, Lo KW, et al. Identification of molecular markers and signaling pathway in endometrial cancer in Hong Kong Chinese women by genome-wide gene expression profiling. Oncogene. 2007;26:1971–1982. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209986. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farmer P, Bonnefoi H, Becette V, et al. Identification of molecular apocrine breast tumours by microarray analysis. Oncogene. 2005;24:4660–4671. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Aust L, Devlin B, Foster SJ, et al. Yield of human adipose-derived adult stem cells from liposuction aspirates. Cytotherapy. 2004;6:7–14. doi: 10.1080/14653240310004539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Singer S, Socci ND, Ambrosini G, et al. Gene expression profiling of liposarcoma identifies distinct biological types/subtypes and potential therapeutic targets in well-differentiated and dedifferentiated liposarcoma. Cancer Res. 2007;67:6626–6636. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yuan JS, Reed A, Chen F, Stewart CN., Jr Statistical analysis of real-time PCR data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:85. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barretina J, Taylor BS, Banerji S, et al. Subtype-specific genomic alterations define new targets for soft-tissue sarcoma therapy. Nat Genet. doi: 10.1038/ng.619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.van de Rijn M, Fletcher JA. Genetics of soft tissue tumors. Annu Rev Pathol. 2006;1:435–466. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pathol.1.110304.100052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Heinrich MC, Corless CL, Duensing A, et al. PDGFRA activating mutations in gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 2003;299:708–710. doi: 10.1126/science.1079666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirota S, Isozaki K, Moriyama Y, et al. Gain-of-function mutations of c-kit in human gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Science. 1998;279:577–580. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5350.577. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tuveson DA, Willis NA, Jacks T, et al. STI571 inactivation of the gastrointestinal stromal tumor c-KIT oncoprotein: biological and clinical implications. Oncogene. 2001;20:5054–5058. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1204704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Halvorsen OJ, Haukaas SA, Akslen LA. Combined loss of PTEN and p27 expression is associated with tumor cell proliferation by Ki-67 and increased risk of recurrent disease in localized prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2003;9:1474–1479. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li X, Tang X, Jablonska B, Aguirre A, Gallo V, Luskin MB. p27(KIP1) regulates neurogenesis in the rostral migratory stream and olfactory bulb of the postnatal mouse. J Neurosci. 2009;29:2902–2914. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4051-08.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gabellini C, Pucci B, Valdivieso P, et al. p27kip1 overexpression promotes paclitaxel-induced apoptosis in pRb-defective SaOs-2 cells. J Cell Biochem. 2006;98:1645–1652. doi: 10.1002/jcb.20900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dai D, Wolf DM, Litman ES, White MJ, Leslie KK. Progesterone inhibits human endometrial cancer cell growth and invasiveness: down-regulation of cellular adhesion molecules through progesterone B receptors. Cancer Res. 2002;62:881–886. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kataoka T, Holler N, Micheau O, et al. Bcl-rambo, a novel Bcl-2 homologue that induces apoptosis via its unique C-terminal extension. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:19548–19554. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010520200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Holleman A, den Boer ML, de Menezes RX, et al. The expression of 70 apoptosis genes in relation to lineage, genetic subtype, cellular drug resistance, and outcome in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 2006;107:769–776. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-07-2930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hilfiker-Kleiner D, Hilfiker A, Kaminski K, et al. Lack of JunD promotes pressure overload-induced apoptosis, hypertrophic growth, and angiogenesis in the heart. Circulation. 2005;112:1470–1477. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.518472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zhou H, Gao J, Lu ZY, Lu L, Dai W, Xu M. Role of c-Fos/JunD in protecting stress-induced cell death. Cell Prolif. 2007;40:431–444. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2184.2007.00444.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Weitzman JB, Fiette L, Matsuo K, Yaniv M. JunD protects cells from p53-dependent senescence and apoptosis. Mol Cell. 2000;6:1109–1119. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.He X, Di Y, Li J, et al. Molecular cloning and characterization of CT120, a novel membrane-associated gene involved in amino acid transport and glutathione metabolism. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2002;297:528–536. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)02227-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.He XH, Li JJ, Xie YH, et al. Altered gene expression profiles of NIH3T3 cells regulated by human lung cancer associated gene CT120. Cell Res. 2004;14:487–496. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7290252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou C, Arslan F, Wee S, et al. PCI proteins eIF3e and eIF3m define distinct translation initiation factor 3 complexes. BMC Biol. 2005;3:14. doi: 10.1186/1741-7007-3-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang L, Pan X, Hershey JW. Individual overexpression of five subunits of human translation initiation factor eIF3 promotes malignant transformation of immortal fibroblast cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:5790–5800. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606284200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.