Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Internal hernias are a rare cause of bowel obstruction in the neonate and present with bilious vomiting. Newborns may be at risk of loss of significant length of bowel if this rare condition is not considered in the differential diagnosis of bilious emesis.

PRESENTATION OF CASE

We report a case of a twin with an internal hernia through a defect in the ileal mesentery who presented with neonatal bowel obstruction. The patient had a microcolon on the contrast enema suggesting that the likely etiology was an intra-uterine event most likely a vascular accident that prevented satisfactory meconium passage into the colon.

discussion

An internal hernia is rarely considered in the differential diagnosis of distal bowel obstruction in a neonate with a microcolon. Congenital trans-mesenteric hernias constitute only 5–10% of internal hernias. True diagnosis of trans-mesenteric hernias is difficult due to lack of specific radiology or laboratory findings to confirm the suspicion.

conclusion

When clinical and radiological findings are not classical, rare possibilities such as an internal hernia must be considered in the differential diagnosis, to avoid catastrophic bowel loss.

Keywords: Internal hernia, Congenital mesenteric defect, Neonatal bowel obstruction

1. Introduction

Herniation through a congenital mesenteric defect is a rare but extremely serious cause of intestinal obstruction. Although termed ‘congenital’ most patients with mesenteric herniation present symptomatically in adulthood and delays in diagnosis are common when the condition manifests in early childhood and infancy. As internal hernias are seldom recognized early due to the non specific accompanying symptoms intestinal obstruction, strangulation, and eventually, necrosis of the segment of bowel protruding through the defect can occur.1 This article describes a case of a neonate presenting with small bowel obstruction resulting from an internal hernia though a congenital mesenteric defect and discusses its management and reviews its pathogenesis.

2. Case report

A set of monozygotic (monochorionic) twins were delivered prematurely at 29 weeks gestation due to fetal distress secondary to knotted and intertwined umbilical cords. One of the twins was diagnosed with transposition of great vessels on the first day of life. The second twin, the subject of this report, was progressing well until the fourth day of life when enteral feeding was initiated. Almost immediately thereafter the patient was noted to have feeding intolerance, with bilious emesis, and a distended abdomen with visible peristalsis. The neonate had some passage of meconium after rectal stimulation. There were no clinical signs of sepsis such as temperature and hemodynamic instability. A presumptive diagnosis of necrotizing enterocolitis was made, based on clinical presentation and the finding of dilated loops on abdominal radiography, and the neonate was started on medical treatment for this. A surgical consultation was requested for persistent dilated loops on the abdominal X-rays (Fig. 1a).

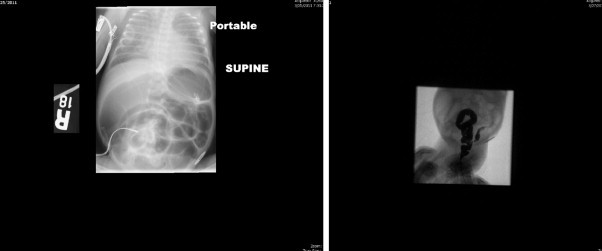

Fig. 1.

(a) Plain X-ray showing dilated loops of small intestine. Subsequent water soluble contrast enema (b) showed a microcolon that could not be visualized in its entirety.

A contrast water-soluble enema was performed to exclude common causes of distal partial small bowel obstruction such as meconium plug syndrome, meconium ileus, Hirschsprung's disease, small left colon syndrome, and intestinal stenosis. Significant findings on this study included a small caliber colon with no evidence of any of the differential diagnoses alluded to (Fig. 1b). Due to the presence of fixed dilated loops on the abdominal films and the presence of a microcolon a decision was taken to proceed to the operating room.

A right upper quadrant exploratory laparotomy was performed. Once the bowel was eviscerated, an internal herniation of 30 cm of proximal ileum through a 4 cm defect in the terminal ileal mesentery was found (Fig. 2). While the herniated bowel itself was viable the herniation had caused impairment in the venous return from the terminal ileum that remained dusky and congested despite reduction of the hernia. We noted that the perfusion of the ileum was based on an intact marginal vessel close to the ileal wall that served as bridging collateral between the ileal branch of the ileo-colic artery and the descending branch of the right colic artery. The terminal ileum was transected through the mesenteric defect with an Endo-GIA stapler, and 30 cm of dusky, dilated and congested terminal ileum was resected. An appendectomy was performed at the same time. The ileo-cecal valve and the last 5 cm of terminal ileum were left intact with its circulation being based on retrograde perfusion through collaterals from the right colic vessel. Saline solution was used to distend both the proximal and distal loops of remaining bowel, and showed no atretic segments. An ileostomy and mucous fistula was created. Rectal biopsies that were performed subsequently showed normal ganglion cells.

Fig. 2.

Mesenteric defect is visible with viable bowel that had herniated. A collateral vessel is seen running along the margin of the intestine and maintained perfusion to this segment of intestine.

3. Discussion

Congenital trans-mesenteric hernias are internal hernias that occur when part of the intestines pass through an abnormal defect in the mesentery of the small bowel or the colon, normally between 2 cm and 3 cm in size. As no hernia sac is involved a considerable length of bowel can protrude through the defect.2,3 Trans-mesenteric hernias are most commonly located in the ileo-cecal region; however, there are reports of herniation through defects in the sigmoid mesocolon. Congenital trans-mesenteric hernias constitute only 5–10% of internal hernias. 30% of the cases remain without symptoms for lifetime.4 The first case of trans-mesenteric hernia was reported in 1836 and was found at autopsy, showing herniation of the cecum through a mesenteric defect near the ileo-cecal valve.5 The exact pathogenesis of the defect formation is still uncertain. Many hypotheses were proposed such as regression of the dorsal mesentery, developmental enlargement of a hypo-vascular area, the rapid lengthening of a segment of mesentery, and compression of the mesentery by the colon during fetal mid-gut herniation into the yolk sac.6,7 Associated anomalies of the gastrointestinal tract have also been reported including Hirschsprung's disease, cystic fibrosis, and most commonly small bowel atresia.8 In one study small bowel atresia was found in 50% of the infants with two-thirds of these being ileal atresia. With the strong association with intestinal atresia it is possible that isolated mesenteric defects represent a forme fruste of intestinal atresia. Less severe vascular accidents cause mesenteric defects without atresia while the more severe ones lead to mesenteric defects and atresia. It is interesting to note that the bridging collateral vessel noted in our case came from the right colonic circulation similar to the persistent ileo-colic vessel that maintains circulation to the terminal ileum in apple peel atresia.

In children, the most common presenting symptom is sudden onset of abdominal pain located frequently in the epigastrium and the peri-umbilical area. As loops of bowel pass in and out through the defect, intermittent obstructive symptoms of abdominal pain, distension, nausea, vomiting, and constipation occur.4 On the other hand, in neonates, most patients remain relatively asymptomatic until they are started on enteral feeds when patients generally present with persistent vomiting and abdominal distention. In the case presented, the diagnosis early on was complicated by the patient's prematurity. Hence, the abdominal distention post enteric feeding was initially seen as a sign for development of necrotizing enterocolitis, which is common within this demographic. The abdominal X-rays performed could only suggest an incomplete distal bowel obstruction, and the demonstration of a microcolon using the contrast enema study left us with the differential diagnoses that included small and large bowel atresias, meconium ileus, meconium plug syndrome, and long segment Hirschsprung's disease.9

True diagnosis of trans-mesenteric hernias is difficult due to lack of specific radiology or laboratory findings to confirm the suspicion. Abdominal X-rays can be helpful as an initial screening tool to differentiate a proximal versus distal bowel obstruction. Once a distal obstruction is recognized, an urgent contrast enema study should be performed which could potentially be both diagnostic and therapeutic in the circumstance of a meconium plug or ileus. However, evidence of a microcolon, together with the failure of the contrast enema to decompress the obstruction should lead one to consider a diagnosis of bowel discontinuity such as an atresia or extraordinary diagnoses such as an internal hernia.8,9 Ultrasound may show dilated loops of meconium filled bowel proximal to the obstruction and collapsed loops distally. The use of CT scans to diagnose trans-mesenteric hernias in children had been proposed, but its role in neonates remains unclear.10 Angiography may show abrupt angulation and displacement of visceral branches as they traverse the mesenteric defect.2 Surgical exploration remains the only definitive way to establish the diagnosis and is considered as an emergency, as patients with acute symptoms and internal herniation have a mortality rate of up to 50%.11 The association of mesenteric defects with monozygotic twinning has been reported.12 One should consider the possibility of internal hernias in the clinical setting of feeding intolerance in monozygotic twins as many commonly done tests to evaluate bowel obstruction in neonates may be normal.

The exact surgical treatment is dependent on the viability of bowel. Volvulus and ischemia are more common in trans-mesenteric hernias as compared to other internal hernias.13,14 It is imperative to inspect the bowel starting from the ligament of Treitz, and follow it throughout the full length of the bowel. Simple untwisting or reduction of the bowel and closure of the mesenteric defect is warranted if the bowel appears viable; resection with either a primary anastamosis versus a creation of a stoma should be performed if the bowel appears gangrenous or perforation is imminent. We also advocate exclusion of associated bowel atresia by intra-luminal saline injection. The use of prophylactic intravenous antibiotics is unnecessary beyond 24 h after surgery, but a therapeutic antibiotic course would be recommended if bowel perforation is present.

4. Conclusion

Trans-mesenteric hernia is a rare but serious disease in the pediatric population, especially in neonates, due to lack of specific clinical signs and symptoms. A high degree of clinical suspicion is warranted to diagnose it in an accurate and timely fashion.

Conflict of interest statement

None.

Funding

None.

Ethical approval

Consent has been obtained from family.

Authors’ contribution

Burjonrappa took care of designing, writing, and revising the article and took complete control of the research.

Along with Burjonrappa, Malit too has contributed immensely in the research as well as in scripting the content.

References

- 1.Blachar A., Federle M.D. Internal hernia: an increasingly common cause of small bowel obstruction. Semin Ultrasound CT MRI. 2002;23:174–183. doi: 10.1016/s0887-2171(02)90003-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ghahremani G.G. Internal abdominal hernias. Surg Clin North Am. 1984;64:393–406. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)43293-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Winterscheid L.C. Mesenteric hernia. In: Nyhus L.M., Harkins H.N., editors. Hernia. JB Lippincott; Philadelphia: 1964. pp. 602–605. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Weber P., Von Lengerke H.J., Oleszczuk-Rascke K., Schleef J., Zimmer K.P. Internal abdominal hernias in childhood. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 1997;25:358–362. doi: 10.1097/00005176-199709000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ming Y.C., Chao H.C., Luo C.C. Congenital mesenteric hernia causing intestinal obstruction in children. Eur J Pediatr. 2007;166:1045–1047. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0377-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Federschmidt F. Embryonal origin of lacunae in mesenteric tissue; the pathologic changes resulting therefrom. Deutsche Ztschr F Chir. 1920;158:205–211. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Menegaux G. Les hernies dites trans-mesocoliques; mesocolon transverse. J Chir. 1934;43:321–325. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy D.A. Internal hernias in infancy and childhood. Surgery. 1964;55:311–315. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Amodio J., Berdon W., Abramson S., Stolar C. Microcolon of prematurirty: a form of functional obstruction. Am J Roentgenol. 1986;146:239–244. doi: 10.2214/ajr.146.2.239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blachar A., Federle M.P., Dodson S.F. Internal hernia: clinical and imaging findings in 17 patients with emphasis on CT criteria. Radiology. 2001;218:68–74. doi: 10.1148/radiology.218.1.r01ja5368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lough J.O., Estrada R.K., Wiglesworth F.W. Internal hernia into Treves’ Field Pouch. Report of two cases and review of literature. J Pediatr Surg. 1969;4:198–207. doi: 10.1016/0022-3468(69)90391-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Page M.P., Ricca R.L., Resnick S.A., Puder M., Fishman S.J. Newborn and toddler intestinal obstruction owing to congenital mesenteric defects. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43:755–758. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2007.11.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Janin Y., Stone A.M., Wise L. Mesenteric hernia. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1980;150:747–754. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaos G., Skondras C. Treves’ field congenital hernias in children: an unsuspected rare cause of acute small bowel obstruction. Pediatr Surg Int. 2007;23:337–342. doi: 10.1007/s00383-007-1877-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]