Abstract

This article is a critical appraisal of the literature on the oral complications of bulimia. The MEDLINE database yielded a total of 82 English-language reports published between 1966 and 2002 that were pertinent to the topic of oral manifestations and treatment of bulimia. The literature is composed primarily of reviews, letters, case reports with or without restorative management, and descriptive studies of small sample sizes. At present, retrospective case-control studies are the only studies available with levels of evidence in the vicinity of 3 to 4. From these studies it is apparent that bulimic women present with a variety of oral and pharyngeal signs and symptoms, including dental caries and tooth erosion, dental pain, increased levels of cariogenic bacteria, orthodontic abnormalities, xerostomia (the subjective complaint of a dry-mouth) and decreased saliva secretion (the objective measure), decreased salivary pH, decreased periodontal disease, parotid enlargement, and swallowing impairments. Dental erosion is the major finding associated with bulimia. Case reports describe restoration of damaged surfaces with porcelain-laminated veneers, dentin-bonded crowns with minimal tooth preparation, composites, and complete–coverage restorations. However, what is really needed is identification of oral markers of bulimic behavior for early detection of bulimic patients by dentists and by physicians that can prevent the deleterious effects of frequent vomiting on the oral/dental tissues.

Bulimia nervosa is a constellation of nutritional and psychological disorders that is characterized by uncontrollable eating binges usually followed by periods of fasting, purging, or vomiting. These bingeing/vomiting episodes presumably affect oral health. Oral symptoms related to bulimia nervosa that have been described in case reports, descriptive studies, and case-control studies include enamel erosion, dental caries, dental pain, orthodontic abnormalities, xerostomia, reduced saliva secretion, parotid enlargement and dysphagia, among others.1–21

All but 2 of the oral symptoms can be reversed: dental caries and tooth erosion. The dental profession can promptly diagnose these pathoses. However, this diagnosis reflects an established condition that leaves the professional with no other option than repair of damaged dental surfaces. Although it is important to diagnose erosion of the teeth in order to advise patients to seek medical treatment, the diagnosis of an established pathosis fails to anticipate its development and progression and does not permit the professional to implement interceptive and preventive strategies.

EPIDEMIOLOGY OF BULIMIA NERVOSA

The eating disorders anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and their variants affect an estimated 5 million Americans yearly.22 Although the prevalence of bulimia nervosa is unknown, the prevalence of dieting is very high. Modern women are bombarded with unrealistic images of what they should look like and what they should achieve. A recent survey of the San Francisco Bay area revealed that 80% of girls aged 8–10 years had already dieted.23 Bulimia nervosa develops as a nutritional imbalance in conjunction with psychological pressures and disorders.24,25 Bulimic women strive to maintain a good self-image by dieting to prevent a gain in weight, but uncontrollable cravings linked to the subjects’ nutritional and metabolic statuses26 lead to frequent bingeing followed by purging or vomiting.

The epidemiology of bulimia nervosa is not precisely known. Bulimia nervosa affects women in late adolescence and early adulthood.23,27–30 Cross-sectional observations indicate that this condition is reaching alarming proportions on college campuses. 30 Bulimic behaviors have been reported to be prevalent in 10% to 20% of all university women,23,28 and in 8% to 20% of high-school girls.27,29 A longitudinal survey of college freshmen women demonstrated that the incidence of bulimia nervosa was 4.2 new cases per 100 women a year.31 More recent data on large cohorts has revealed that the prevalence of bulimic behaviors that include vomiting ranges from 4.8% to 12.5%.32,33

ORAL DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT OF BULIMICS

DIAGNOSIS

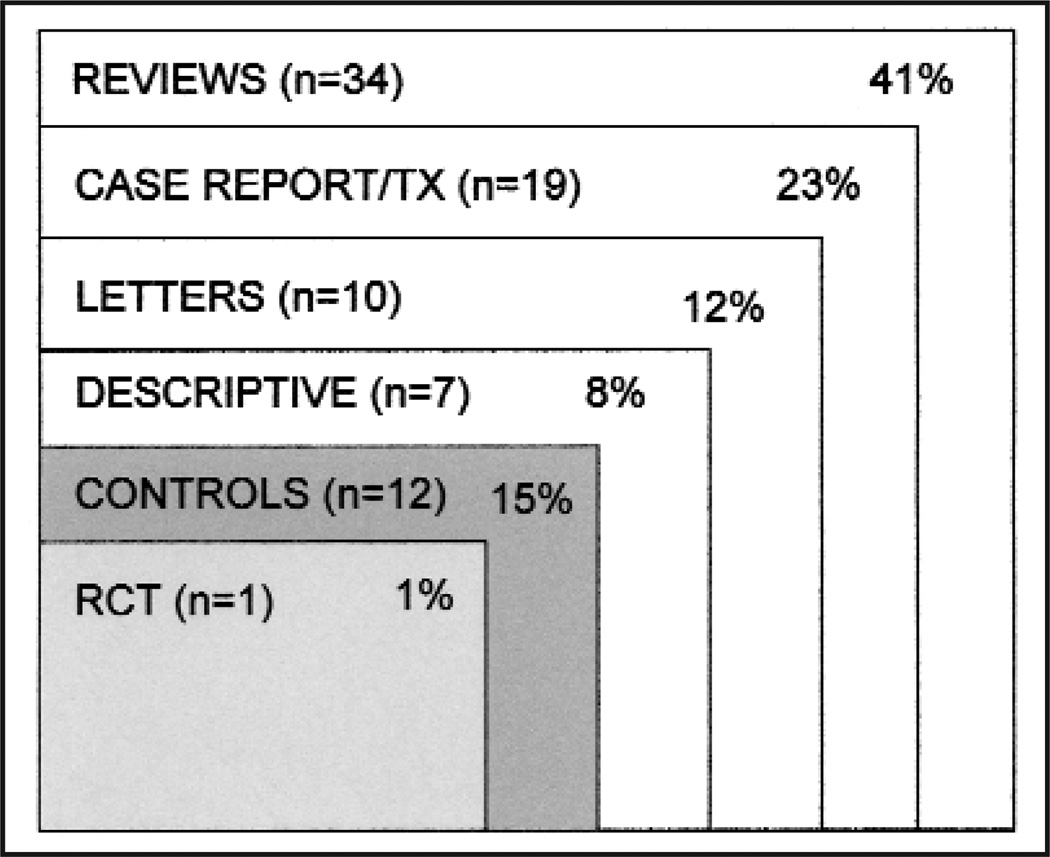

This review is a critical appraisal of the literature published between 1966 and 2002, not a systematic review. To identify relevant articles, the MEDLINE database was searched. Search terms included bulimia, dental and oral disorders, eating disorders, and the index to the dental literature. The search produced a total of 82 reports in the English language. The dental and medical literature pertinent to the topic of oral manifestations and treatment of bulimia nervosa (Fig 1) is basically composed of reviews, letters, case reports with or without restorative management, and descriptive studies of small sample sizes. Although the body of evidence in these reports can be thought-provoking and stimulate further research, it lacks the presence of comparison groups and cannot provide evidence for causality.

Fig 1.

Medline Search (1966–2002) on related literature of oral symptoms and management of patients with bulimia nervosa. TX, treatment; RCT, randomized clinical trial.

A powerful study design for investigating the oral manifestations of bulimia nervosa would be a cohort study in which exposed and nonexposed participants are followed overtime with the outcome of interest being studied. However, as of now, this type of study design on the oral manifestations of bulimia nervosa does not exist. At present, a relatively small number of retrospective case-control studies are the only studies available for assessment (Fig 1). Moreover, most of these studies were performed under less than ideal conditions (Table). All the studies lack randomization, cases are not always matched to controls, and blindness is often not apparent. Despite these limitations, the studies are the only evidence available on the oral manifestations of bulimia nervosa. It is apparent from them that bulimic women present with a variety of oral and pharyngeal signs and symptoms, including dental caries and tooth erosion, dental pain, increased levels of cariogenic bacteria, orthodontic abnormalities, xerostomia (the subjective complaint of a dry mouth) and decreased saliva secretion (the objective measurement of dry mouth), decreased salivary pH, decreased periodontal disease, parotid enlargement, and dysphagia, ie, swallowing impairment (Table).

Table.

Case-control studies on the oral manifestations of bulimia nervosa

| First author |

Publication year |

Cases/controls | Sample size blindness |

Randomization/ Study type |

Significant results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Milosevic | 1989 (10) | n=40/n=58 | No/Yes | Oral exam | Age-matched NS |

| Bretz | 1989 (46) | n=14 (bulimics)/ n=13 (high S mutans) n=12 (low S mutans) |

No/Yes | Oral flora | Age, SES-matched ↑levels of S sobrinus ↑levels of lactobacilli |

| Roberts | 1989 (7) | n=13/n=13 | No/No | Swallowing patterns | Age-matched ↑dysphagia |

| Altshuler | 1990 (2) | n=75/n=75 | No/No | Oral exam | Age-matched ↑erosion ↑dental caries ↑hypersensitivity ↑parotid enlargement ↑xerostomia |

| Tylenda | 1991 (11) | n=15/n=15 | No/No | Saliva chemistry | Age-, race-matched NS |

| O’Reilly | 1991 (4) | n=24/n=24 | No/Yes | Orthodontic exam | Age-matched ↑open-bite |

| Philipp | 1991 (5) | n=41/n=50 | No/No | Oral/serum exam | Not matched ↓gingival bleeding ↑erosion ↑parotid enlargement ↑serum amylase |

| Robb | 1995 (14) | n=39/n=39 | No/No | Oral exam | Age, SES-matched ↑erosion |

| Milosevic | 1996 (9) | n=9 (bul. with erosion)/ n=10 (bul. no erosion) |

No/No | Saliva chemistry/secretion | Not matched ↓stimulated saliva secretion ↓saliva bicarbonate ↑saliva viscosity ↓enamel calcium |

| Touyz | 1993 (15) | n=15/n=15 | No/No | Oral exam/flora | Age-matched ↓salivary pH ↓plaque levels ↓periodontal disease |

| Rytomaa | 1998 (8) | n=35/n=105 | No/Yes | Oral exam/saliva | Age, SES-matched ↓unstimulated saliva secretion ↑erosion ↑dental caries ↑hypersensitivity |

| Ohrn | 1999 (17) | n=81/n=52 | No/No | Oral Exam/saliva/flora | Not matched ↓unstimulated saliva secretion ↑erosion ↑DMFS ↑S mutans levels ↑lactobacilli levels |

NS, Findings between bulimics and controls not significantly different; S mutans, Streptococcus mutans salivary levels; SES, socioeconomic status; S sobrinus, Streptococcus sobrinus salivary levels; DMFS, number of decayed, missing and filled surfaces; ↑, significant increase compared to control(s); ↓, significant decrease compared to control(s).

The most frequent finding in these case-control studies was the presence of erosion or pathological wear on tooth surfaces. Dental erosion is defined as loss of dental tissue without the involvement of bacteria.34 The risk for dental erosion is increased in individuals who consume large amounts of citrus fruits, soft drinks and sports drinks, in gastric regurgitators or refluxers, and in vomiters.35 Bulimic women are known to be frequent vomiters and to present with high frequency and severity of erosion on tooth surfaces.36 The emergence of gastric contents in the oral cavity can lower the oral pH.1,5,15 The average pH upon analysis of gastric contents of bulimic patients is about 3.8.9 In addition, a decrease in saliva secretion rate is often observed in bulimics as a result of parotid dysfunction,2,5 the use of antidepressants,37 or a combination of both. Collectively, all of these factors can significantly contribute to enamel dissolution. Figs 2 and 3, exemplify the presence of erosion on tooth surfaces of bulimics. Unfortunately, the one option a dentist has upon making this clinical diagnosis is to restore the damaged surfaces and possibly make a referral for medical consultation.

Fig 2.

Erosion of dental surfaces in a bulimic patient: upper jaw.

Fig 3.

Erosion of dental surfaces in a bulimic patient: facial view.

TREATMENT

Dental erosion can alter the aesthetics of bulimic women (Figs 2 and 3), provoke dental hypersensitivity and pain,2,8 and result in tooth loss.1 The literature on the treatment of bulimic patients is restricted to case reports of restoration of the damaged surfaces with porcelain-laminated veneers, dentin-bonded crowns with minimal tooth preparation, composites, and complete–coverage restorations.18–21,36,38–45 Ideally, the interface of dentists and physicians in the management of bulimia nervosa would prevent further dental tissue damage. However, no one can predict whether the patient will undergo remission or relapse after medical treatment.

The reviews include several anecdotal suggestions on instructing bulimics in vomiting or after-vomiting procedures to prevent further enamel demineralization. Those include the use of fluorides to strengthen the enamel and to prevent further demineralization, rinsing with tap water, and custom trays with alkaline substances after or while vomiting, among others. These suggestions need to be tested in properly designed clinical trials.

EARLY DETECTION OF BULIMIC PATIENTS

MARKERS OF BULIMIC BEHAVIOR

It has previously been reported that the presence of Streptococcus sobrinus may be an indicator of bulimic behaviors that include vomiting.46 Bulimic patients exhibit high salivary levels of S sobrinus when compared with age-matched controls. S sobrinus is highly dependent for sucrose-mediated attachment to the pellicle on the tooth surface,47 so frequent bingeing (sucrose ingestion) would favor its colonization. It has also been shown that S sobrinus is highly active at low pH values.48 Accordingly, S sobrinus may be highly active in acidic environments reflecting current emetic activity. The potential for having a marker of bulimic behavior for early detection of bulimic patients in the dental setting is of interest and needs to be further confirmed by different groups of investigators.

EFFECTS OF MEDICAL TREATMENT ON MARKERS OF BULIMIC BEHAVIOR

Only one randomized clinical trial (Fig 1) evaluated the effects of medical treatment on the oral environment of bulimics with emphasis on the microbiota associated with dental caries.

This double-blind placebo-based clinical trial of the effects of fluoxetine (antidepressant) on fluctuations of salivary levels of S sobrinus36 demonstrated that the salivary levels of these organisms could serve as an objectively measured indicator of patient compliance with antibulimic therapy. Patients who were in the test group initially had high levels of S sobrinus in their saliva that were comparable to levels of patients of the placebo group. After 4 months patients taking fluoxetine had significantly decreased levels of S sobrinus that paralleled a decrease in binging and purging episodes. These findings can direct further research aimed at the early detection of markers of bulimic behavior and treatment managed concomitantly by physicians and dentists.

WHAT EVIDENCE IS NEEDED

At present it is fair to conclude that dental erosion is a marked characteristic of bulimic behavior that includes vomiting. Several research protocols in this field, however, need to be conducted. These include (1) longitudinal cohort studies designed to measure oral manifestations of bulimic behavior; (2) randomized clinical trials designed to evaluate the effects of treatment protocols on selected outcomes; and (3) identification of oral markers of bulimic behavior for early detection by dentists and physicians that can prevent the deleterious effects of frequent vomiting on the oral and dental tissues.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hurst PS, Lacey JH, Crisp AH. Teeth, vomiting and diet: a study of the dental characteristics of seventeen anorexia nervosa patients. Postgrad Med J. 1977;53:298–305. doi: 10.1136/pgmj.53.620.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Altshuler BD, Dechow PC, Waller DA, Hardy BW. An investigation of the oral pathologies occurring in bulimia nervosa. Internat J Eat Disorders. 1990;9:191–199. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Spigset O. Oral symptoms in bulimia nervosa. A survey of 34 cases. Acta Odontol Scand. 1991;49:335–339. doi: 10.3109/00016359109005929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.O’Reilly RL, O’Riordan JW, Greenwood AM. Orthodontic abnormalities in patients with eating disorders. Internat Dent J. 1991;41:212–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Philipp E, Willerhausen-Zonnchen B, Hamm G, Pirke KM. Oral and dental characteristics in bulimic and anorectic patients. Internat J Eat Disord. 1991;10:423–431. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Andrews FF. Dental erosion due to anorexia nervosa with bulimia. Br Dent J. 1982;152:89–90. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4804753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roberts MW, Tylenda CA, Sonies BC, Elin RJ. Dysphagia in bulimia nervosa. Dysphagia. 1989;4:106–111. doi: 10.1007/BF02407154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rytomaa I, Jarvinen V, Kanerva R, Heinonen OP. Bulimia and tooth erosion. Acta Odontol Scand. 1998;56:36–40. doi: 10.1080/000163598423045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Milosevic A, Dawson LJ. Salivary factors in vomiting bulimics with and without pathological tooth wear. Caries Res. 1996;30:361–366. doi: 10.1159/000262343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Milosevic A, Slade PD. The orodental status of anorexics and bulimics. Br Dent J. 1989;167:66. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4806915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Roberts WB, Li SH. Oral findings in anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa: a study of 47 cases. J Am Dent Assoc. 1987;115:407–410. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.1987.0262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tylenda CA, Roberts MW, Elin RJ, Li SH, Altemus M. Bulimia nervosa. J Am Dent Assoc. 1991;122:37. doi: 10.1016/s0002-8177(91)26015-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brady JP. Parotid enlargement in bulimia. J Fam Prac. 1985;20:496–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Robb ND, Smith BGN, Geidrys-Leeper E. The distribution of erosion in the dentitions of patients with eating disorders. Br Dent J. 1995;178:171–175. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4808695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Touyz SW, Liew VP, Tseng P, Frisken K, Williams H, Beumont PJV. Oral and dental complications in dieting disorders. Internat J Eat Disord. 1993;14:341–348. doi: 10.1002/1098-108x(199311)14:3<341::aid-eat2260140312>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bidwell HL, Dent D, Sharp JG. Bulimia-induced dental erosion in a male patient. Quintessence Internat. 1999;30:135–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Öhrn R, Enzell K, Angmar-Månsson B. Oral status of 81 subjects with eating disorders. Eur J Oral Sciences. 1999;107:157–163. doi: 10.1046/j.0909-8836.1999.eos1070301.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milosevic A, Jones C. Use of resin-bonded ceramic crowns in a bulimic patient with severe tooth erosion. Quintessence Internat. 1996;27:123–127. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Burke FJT. Treatment of loss of tooth substance using dentine-bonded crowns: report of a case. Dent Update. 1998;25:235–240. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bonilla ED, Luna O. Oral rehabilitation of a bulimic patient: A case report. Quintessence Internat. 2001;32:469–475. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Woodmansey KF. Recognition of bulimia nervosa in dental patients: implications for dental care providers. Gen Dent. 2000;48:48–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Becker AE, Grinspoon SK, Klibanski A, Herzog DB. Eating disorders. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1092–1098. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904083401407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Killen JD, Taylor CB, Telch MJ, Robinson TN, Maron DJ, Saylor KE. Depressive symptoms and substance use among adolescent binge eaters and purgers: a defined population study. Am J Pub Health. 1987;77:1539–1541. doi: 10.2105/ajph.77.12.1539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Taylor ME, Lawrence RW, Allen KGD. Nutritional assessment of college age women with bulimina. Int J Eat Disord. 1986;5:59–74. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beumont PJV, Chambers TL, Rouse L, Abraham SF. The diet composition and nutritional knowledge of patients with anorexia nervosa. J Hum Nutr. 1981;35:265–273. doi: 10.3109/09637488109143052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Roesenthal NE, Hefferman MM. Bulimia, carbohydrate craving and depression: a central connection? In: Wurtman RJ, Wurtman JJ, editors. Nutrition and the brain. Vol 7. New York: Raven Press; 1986. pp. 139–166. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Carter JA, Duncan PA. The practice of self-induced vomiting among high school females. J Sch Health. 54:450–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1746-1561.1984.tb08911.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Halmi KA, Falk JR, Schwartz E. Binge-eating and vomiting: a survey of a college population. Psychol Med. 1981;11:697–706. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700041192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schotte DE, Stunkard AJ. Bulimia vs bulimic behaviors on a college campus. JAMA. 1987;258:1213–1215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Drewnowski A, Yee DK, Krahn DD. Bulimia in college women: incidence and recovery rates. Am J Psychiatry. 1988;145:753–755. doi: 10.1176/ajp.145.6.753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pyle RL, Halvorson PA, Neuman PA, et al. The increasing prevalence of bulimia in freshman college students. Int J Eat Disord. 1986;5:631–647. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sullivan PF, Bulik CM, Kendler KS. The epidemiology and classification of bulimia nervosa. Psychol Med. 1998;28:599–610. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McNulty PA. Prevalence and contributing factors of eating disorder behaviors in a population of female Navy nurses. Mil Med. 1997;162:703–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pindborg JJ. Pathology of dental hard tissues. Copenhagen: Munksgaard; 1970. pp. 312–321. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jarvinen VK, Rytomaa II, Heinonen OP. Risk factors in dental erosion. J Dent Res. 1991;70:942–947. doi: 10.1177/00220345910700060601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jones RRH, Cleaton-Jones P. Depth and area of dental erosions, and dental caries, in bulimic women. J Dent Res. 1989;68:1275–1278. doi: 10.1177/00220345890680081201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Bretz WA, Krahn DD, Drury M, Schork N, Loesche WJ. Effects of fluoxetine on the oral environment of bulimics. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1993;8:62–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1993.tb00545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Little JW. Eating disorders: dental implications. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2002;93:138–143. doi: 10.1067/moe.2002.116598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schmidt U, Treasure J. Eating disorders and the dental practitioner. Eur J Prosthodont Restor Dent. 1997;5:161–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bouquot JE, Seime RJ. Bulimia nervosa: dental perspectives. Pract Periodontics Aesthet Dent. 1997;9:655–663. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Burke FJT, Bell TJ, Ismail N, Hartley P. Bulimia: Implications for the practising dentist. Brit Dent J. 1996;180:412–416. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4809109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Robb ND, Smith BGN. Anorexia and bulimia nervosa (the eating disorders): conditions of interest to the dental practitioner. J Dent. 1996;24:7–16. doi: 10.1016/0300-5712(95)00002-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zachariasen RD. Oral manifestations of bulimia nervosa. Women Health. 1995;22:67–76. doi: 10.1300/J013v22n04_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Milosevic A. Eating disorders and the dentist. Brit Dent J. 1999;186:109–113. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4800036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mueller JA. Eating disorders: identification and intervention. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2001;2:98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Bretz WA, Krahn DD, Drewnowski A, Loesche WJ. Salivary levels of putative cariogenic organisms in patients with eating disorders. Oral Microbiol Immunol. 1989;4:230–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-302x.1989.tb00258.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loesche WJ. Role of Streptococcus mutans in human dental decay. Microbiol Reviews. 1986;50:353–380. doi: 10.1128/mr.50.4.353-380.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeSoet JJ, Toors FA, DeGraaff J. Acidogenesis by oral streptococci at different pH values. Caries Res. 1989;23:14–17. doi: 10.1159/000261148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]