Abstract

BACKGROUND:

The aim of this study was to establish the incidence of postoperative complications after single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

MATERIALS AND METHODS:

A literature search was performed using the PubMed database. Search terms included single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy, single port cholecystectomy, minimal invasive laparoscopic cholecystectomy, nearly scarless cholecystectomy and complications.

RESULTS:

A total of 38 articles meeting the selection criteria were reviewed. A total of 1180 patients were selected to undergo single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Introduction of extra ports was necessary in 4% of the patients. Conversion to open cholecystectomy was required in 0.4% of the patients. Laparoscopic cholangiography was attempted in 4% of the patients. The incidence of major complications requiring surgical intervention or ERCP with stenting was 1.7%. The mortality rate was zero.

CONCLUSION:

Although the number of complications after single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy seems favourable, it is too early to conclude that single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy is a safe procedure. Large randomised controlled trials will be necessary to further establish its safety.

Keywords: Complications, laparoscopic cholecystectomy, single port access surgery, surgery

INTRODUCTION

Surgery of the gallbladder has evolved tremendously over the past decades. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy is considered the gold standard for gallbladder removal and is the most common laparoscopic procedure worldwide.[1] The tendency of minimising surgical trauma encourages the use of new approaches in laparoscopic surgery. In recent times, the innovative techniques of Natural Orifice Transluminal Endoscopic Surgery (NOTES) and Single Incision laparoscopic Surgery (SILS) have been applied in gallbladder removal as a step forward toward nearly scarless surgery.

Navarra et al. performed the first SILS cholecystectomy in 1997 using two trocars through one subumbilical incision and three abdominal stay sutures to aid in gallbladder retraction.[2]

Thereafter, other early experiences with single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy have been described. Although multiple groups have reported initial success with a single umbilical incision, no consensus exists concerning the optimum technique for this operation.[3]

The advantages of SILS are not yet clearly defined. It has been suggested that SILS has the potential advantages of reduced postoperative pain, faster return to work, reduced port-site complications and improved cosmesis.[4]

There are safety concerns regarding this technique due to the possible decreased visualisation or exposure, with a lack of triangulation and clashing of instruments. To date, no large safety and feasibility study has been published. It would be not acceptable to trade increased patient comfort for a higher complication rate, particularly if this involves common bile duct injury.

The objective of this study is to describe the cumulative experience of SILS with emphasis on the reported postoperative complications.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A literature search was performed using the Pubmed database. Search terms included single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy, single port cholecystectomy, minimal invasive laparoscopic cholecystectomy, nearly scarless cholecystectomy and complications. Articles including patients who underwent single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy were selected. Furthermore, references of these articles were checked for other relevant reports. Only English articles were reviewed, dated 1997 till February 2010. All cases described here concerned adult patients, aged 18 years and older. To date, there are no randomised controlled trials comparing single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy with multi-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Although there were individual variations in the precise operative techniques used, all procedures were intended to be performed through one single subumbilical incision.

Either specially developed ports or conventional trocars were inserted through this incision. There were individual variations in retraction of the gallbladder, which could be done by additional transabdominal wall sutures or K wires. It was considered the surgeon's preference to use a 0-degree or 30-degree laparoscope. Only those reports were considered in which the number of additional trocar insertion was given. We classified the complications as major or minor, depending on the consequences of the complications. If a complication could be managed with conservative treatment, we defined it as a minor complication. When intervention (drainage readmission or surgery) was necessary, the complication was defined as major.

RESULTS

A total of 38 articles meeting the selection criteria were reviewed. A total of 1180 patients undergoing single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy were described.

Selection of Patients

Indications for gallbladder removal varied from cholecystolithiasis, biliary colic, acute cholecystitis, biliary polyps, biliary dyskinesia and biliary pancreatitis. However, uncomplicated cholecystolithiasis was the main indication. In most articles, patients were preselected regarding indication and Body Mass Index (BMI). In five articles, patients with cholecystitis were included.[4–8] In two reports, patients were only selected if they were classified as American Society of Anaesthesiologists Classification (ASA I or II).[9,10] In seven others, it was explicitly stated that the selected patients had a BMI of 35 kg/m or less.[10–17] In five studies, no clear inclusion criteria were mentioned.[18–22]

Operative Technique

Introduction into the abdomen was performed through one single umbilical incision. A total of 1037 patients underwent a single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy, through one umbilical skin incision with several separate fascial incisions. The length of the umbilical skin incision varied from 12 to 20 mm.[3,5,11–13,19,21–25] Specially developed ports (e.g., SILS-port™, Covidien, Inc., Norwalk CT, USA Triport™ advanced surgical Concepts, W, Ireland, Airseal™ Surgiquest, Inc., Orange, CT, USA and Gelport™, Alexis, applied Medical, Rancho Santa margarita, CA, USA) or wound retractors (Alexis™, applied Medical, Rancho Santa margarita, CA, USA and SITRAC device™, Edlo company, Porto Alegre, Brazil) were used in 143 patients. With these devices, a single fascial incision is used.

Regarding retraction of the gallbladder, in 15 articles, no extra transabdominal sutures or retracting instruments were used. Instead, flexible instruments with articulating graspers were used. In nine articles, one transabdominal suture is placed at the right subcostal margin, which is then placed through the fundus of the gallbladder to retract it cephalad. This suture acts as the surgeon's left hand and can retract the gallbladder to the left or right during the procedure without the use of an extra laparoscopic grasper. In three articles, two transabdominal sutures were used for gallbladder retraction. One needle suture is placed subcostally in the midclavicular line at the right side, which is then placed through the fundus of the gallbladder and the second transabdominal suture was placed subxiphoidal through the infundibulum from medial to lateral. Clips are then applied to the medial and lateral aspects of the infundibulum at the insertion and exit of the latter suture. In three articles, three transabdominal sutures are placed. Two sutures at the right subcostal margin in the dome of the gallbladder and a third suture was placed at the infundibulum from the midline of the abdomen to the right upper quadrant. This final suture was held in place by a second pass through the gallbladder, locking the suture at the base of the gallbladder. Schlager et al. used transabdominal endoloops; these were introduced in the peritoneal cavity through a 5-mm trocar and attached to the gallbladder fundus, which is then retracted anteriorly to the abdominal wall and exits the abdomen at the right subcostal margin. They also used the Endograb, which is an internal anchored retracting device that can be introduced in the abdomen through a 5-mm port. Once deployed, one of the two grasping ends is attached to the gallbladder, while the other is anchored to the abdominal wall, leaving no visible marks.[6] In one article, a small 25-mm incision is made at the right upper quadrant to introduce a minigrasper (20 mm) to retract the gallbladder.[26]

In 49 cases, additional ports were inserted. Main reasons for extra port insertion were visualisation problems and bleeding.[6,7,9–14,18,23,27–30]

When additional ports were needed, in 22 cases, just one extra port was necessary to complete the procedure safely. In the other cases, a conventional multi-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy was performed. Conversion to the classic open cholecystectomy was indicated in five patients. Main reasons for this type of conversion were bleeding and adhesions. In 0.04% of the patients, an intraoperative cholangiogram was performed.[2,5,11]

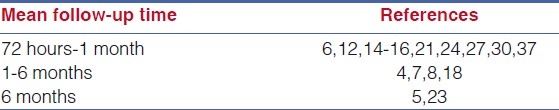

The mean time of follow-up was only described in 16 articles, follow-up varied from 72 hours to 24 months.

Complications

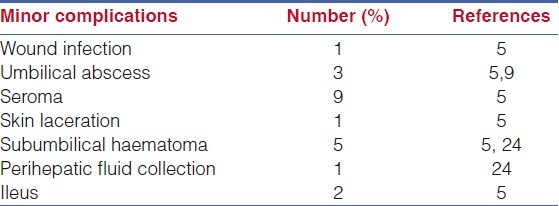

Minor complications, treated conservatively, are listed in Table 1. Intraoperative bile leakage due to gallbladder perforation was reported in 18 patients, although this parameter was not described in each article. Wound seroma was described in 17 patients, a subcutaneous wound infection in eight, a subumbilical haematoma in five, a paralytic ileus in two,[5] a skin laceration in one and a perihepatic fluid collection in another patient.[5,9,10,13,24] In one patient, a temporary bleeding from a mesenteric injury was caused due to grasping of the small bowel mesentery during removal of the wound retractor.[5] Conservative treatment was installed for all these complications and consisted of a wait and see policy or administration of antibiotics.

Table 1.

Minor complications, 24 cases, 2%

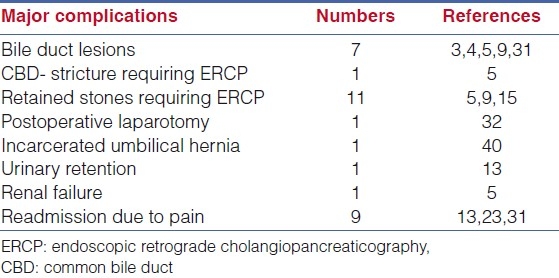

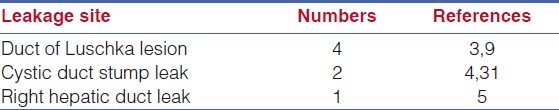

The major complications, defined as those requiring intervention or readmission, are listed in Table 2. In 11 patients, a retained stone was found in the common bile duct (CBD) for which an Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) -guided drainage with incision of the papilla was indicated.[5,9,15] There were nine readmissions due to pain, treated with extra painkillers. Seven postoperative symptomatic bile leaks (0.6%) were described. Four leaks were due to accessory duct leaks.[3,9] Two leaks were caused by a cystic duct stump leak.[4,31] There was one lesion of the right hepatic duct, caused by electrocautery. All these leaks were treated with an Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP) and stent placement [Table 3]. One patient had urinary retention and required catheter insertion.[13] One umbilical hernia was seen, which was treated surgically because of incarceration.[15] One patient suffered from renal failure.[5] No additional information regarding this renal failure was given. One biliary stricture was successfully treated 1 year after the primary operation with dilation through endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreaticography (ERCP), with resolution and normalisation of liver function tests [Table 2].[5] One laparotomy was necessary due to bleeding after injury of the vesical artery. This was noted 3 hours after single incision laparoscopy.[32] There were no reported deaths in these studies.

Table 2.

Major complications, 32 patients (2.7%)

Table 3.

Bile duct injuries (7 cases, 0.6%)

DISCUSSION

SILS marks the beginning of a new era in the field of surgery. SILS purports to offer reduced postoperative pain, faster return to work, less port-related complications and better cosmesis. Some reports suggest a promising future for this innovative technique.[1] This is a preliminary conclusion as long as the safety of this procedure has not been established yet.

One of the questions regarding safety of SILS is the difficulty to attain similar critical view of safety as in conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy due to limited instrumentation, clashing of instrumentation and lack of triangulation. It seems likely that these aspects result in a learning curve in which increased incidence of complications is likely to occur.

In order for a newly developed technique to be adopted or favoured above the gold standard, it should at least be as safe as this procedure with preferably extra advantages.[33]

The present study analyses the frequency of postoperative complications after single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy in order to elucidate its safety.

The most feared complication after laparoscopic cholecystectomy is bile duct injury. Other major, more frequent complications are haemorrhage, subhepatic abscesses and those lesions that require surgical intervention or stenting.[34–36]

Major complications, requiring any intervention of readmission, occurred in 2.7% of the patients, as listed in Table 3.

Intervention by either ERCP and stenting or surgery was necessary in 1.7% of the cases. The most feared complication after cholecystectomy, bile duct lesions (duct of Luschka, right hepatic duct and cystic duct stump leakage) occurred in 0.6% of patients. In addition, in 0.08% of patients, a biliary stricture occurred which may be due to missed bile duct injury and/or arterial laceration.

We could not extract from the articles whether the major complications were related to more demanding cases such as acute cholecystitis. Also, it was not mentioned whether they occurred in cases with obscured anatomy, requiring extra ports to be inserted.

One could assume that the lack of experience, and therefore the learning curve was a determining factor for causing complications. Indeed, in 17 articles, the experience of SILS was restricted to 15 patients or less.[7,8,18–22,25,26,33,37–41]

We noted one report of an umbilical hernia, which was incarcerated and needed surgery. Since the median follow-up time is very low, there is probably an underestimation of this complication. One could assume that the number of umbilical herniation would be higher in the single incision group due to the fact that the umbilical incision might be slightly longer than the umbilical incision seen in the conventional laparoscopic cholecystectomy. On top of the length of the incision, the introduction of the larger single-incision-ports may give extra pressure and tension on the tissue, causing more damage and leading to possible more herniation at the entry site.

Although the number of complications reported seems favourable, it is too early to conclude that SILS is a safe procedure. Operations were performed on preselected patients, as obese patients and those with acute cholecystitis were avoided in most studies. Moreover, it is likely that these early reports on a new technique originate from expert centres with special interest in endoscopic surgery. Finally, follow-up is relatively short in most series [Table 4], therefore some long-term complications as port site herniation may be underestimated. For these reasons, this review is biased by underreporting of complications as compared to the situation where the technique is performed in general practice on a wider selection of patients.

Table 4.

Mean follow-up period after single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy

This retrospective review of 1180 cases is too early to draw definite conclusions. The first results of cumulative experience on single incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy are promising. The exact position of the technique can only be established in a prospective randomised setting.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Chamberlain RS, Sakpal SV. A comprehensive review of single-incision laparoscopic surgery and natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery techniques for cholecystectomy. J Gastroint Surg. 2009;13:1733–40. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-0902-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Navarra G, Pozza E, Occhionorelli S, Carcoforo P, Doninin I. One-wound lapariscopic cholecystectomy. Br J Surg. 1997;84:695. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chow A, Purkayastha S, Aziz O, Paraskeva P. Single-insicion lasparoscopic surgery for cholecystectomy: An evolving technique. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:709–14. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0655-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Edwards C, Bradshaw A, Ahearne A, Dematos P, Humble T, Johnson R, et al. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy is feasible: Initial experience with 80 cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2241–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0943-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Curcillo PG, Wu SA, Podolsky E, Graybeal C, Katkhouda N, Saenz A, et al. Single-port-access (SPA) cholecystectomy: A multi-institutional report of the first 297 cases. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1854–60. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0856-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schlager A, Khalaileh A, Shussman N, Elazary R, Keidar A, Pikarsky A, et al. Providing more through less: Current methods of retraction in SIMIS and NOTES cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1542–6. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0807-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Podolsky ER, Rottman SJ, Curcillo PG. Single port access (SPA) cholecystectomy: Two year follow-up. JSLS. 2009;13:528–35. doi: 10.4293/108680809X12589998404245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Piskun G, Rajpal S. Transumbilical Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy utilizes no incisions outside the umbilicus. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 1999;9:361–4. doi: 10.1089/lap.1999.9.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Roberts KE, Solomon D, Duffy AJ, Bell RL. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A surgeon's initial experience with 56 consecutive cases and a review of the literature. J Gastroint Surg. 2010;14:506–10. doi: 10.1007/s11605-009-1116-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tsimoyiannis EC, Tsimogiannis KE, Pappas-Gogos G, Farantos C, Benetatos N, Mavridou P, et al. Different pain scores in single transumbilical incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy versus classic laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A randomized controlled trial. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1842–8. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0887-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuon Lee S, You PK, Park JH, Kim HJ, Lee KK, Kim DG. Single port transumbilical laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A preliminary Study in 37 patients with gallbladder disease. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2009;19:495–9. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ersin S, Firat O, Sozbilen M. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Is it more than a challenge? Surg Endosc. 2010;24:68–71. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0543-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hodgett SE, Hernandeze JM, Morton CA, Ross SB, Albrink M, Rosemurgy AS. Laparoendoscopic Single Site (LESS) cholecystectomy. J Gastroint Surg. 2009;13:188–92. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0735-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirschniak A, Bollman S, Pointner R, Granderath FA. Transumbilical single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Preliminary experiences. Surg Laparosc Endosc Perct Tech. 2009;19:436–8. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3181c3f12b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rivas H, Varela E, Scoot D. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Initial evaluation of a large series of patients. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1403–12. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0786-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hong TH, You YK, Lee KH. Trransumbilical single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Scarless cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1393–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0252-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hong T, You YK. Transumbilical single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1393–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0252-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Merchant AM, Cook MW, White BC, Davis SS, Sweeney JF, lin E. Transumbilical Gelportt Access techniques for performing single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) J Gastroint Surg. 2009;13:159–62. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0737-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Aftinos JN, Forrester GJ, Binenbaum SJ, Harvey EJ, Kim GJ, Teixeira JA. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy using flexible endoscopy: Saline infiltration gallbladder fossa dissection technique. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2610–4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0415-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Langwieler TE, Nimmesgern T, Back M. Single-port access in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1138–41. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0389-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Petrotos AC, Molinelli BM. Single-incision multiport laparoendoscopic surgery: Early evaluation of SIMPLE cholecystectomy in a community setting. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:2631–4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0369-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gumbs AA, Milone L, Sinba P. Totally transumbilical laparoscopic cholecystectomy. J Gastroint Surg. 2009;13:533–4. doi: 10.1007/s11605-008-0614-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Erbella J, Bunch G. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: The first 100 outpatients. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1958–61. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-0886-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tacchino R, Greco E, Matera D. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Surgery without a visible scar. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:866–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0147-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirano Y, Watanabe T, Uchida T, Yoshida S, Tawaraya K, Kato H, et al. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Single institution experience and literature review. World J Gatroenterol. 2010;16:270–4. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v16.i2.270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhu JF, Hu H, Ma YZ, Xu MZ, Li F. Transumbilical endoscopic surgery: A preliminary report. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:813–7. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Romanelli J, Roshek T, Lynn D, Earle D. Single-port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Initial experience. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:1374–9. doi: 10.1007/s00464-009-0781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Phillip SR, Miedema BW, Thaler K. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy using conventional instruments: Early experience in comparison with the gold standard. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;290:632–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.07.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rao PR, Bhagwat SM, Rane A, Rao PP. The feasibility of single port laparoscopic cholecystectomy: A pilot study of 20 cases. HPB (Oxford) 2008;10:336–40. doi: 10.1080/13651820802276622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhu JF, Hu H, Ma YZ, Xu MZ. Totally transumbilical endoscopic cholecystectomy without visible abdominal scar using improved instruments. Surg Endosc. 2009;23:1781–4. doi: 10.1007/s00464-008-0228-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernandez JM, Morton CA, Ross S, Albrink M, Rosemurgy AS. Laparoendoscopic single site cholecystectomy: The first 100 patients. Am Surg. 2009;75:681–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Misiak A, Szczepanik AB. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy with single incision laparoscopic surgery. Pol Merkur Lekarski. 2009;161:372–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Duca S, Baja, Al-Haijar N, Iancu C, Puia IC, Munteanu D, et al. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Incidents and complications: A retrospective analysis of 9542 consecutive laparoscopic operations. HPB (Oxford) 2003;5:152–8. doi: 10.1080/13651820310015293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dantas de Campos Martins M, Skinovsky J, Coelho DE, Ramos A, Galvão Neto MP, Rodrigues J, et al. Cholecystectomy by single trocar acces (SITRACC): The first multicentre study. Surg Innov. 2009;16:313. doi: 10.1177/1553350609353422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tuveri M. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy: Complications and conversions with the 3-trocar technique: A 10-year review. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percut Tech. 2007;17:380–4. doi: 10.1097/SLE.0b013e3180dca5d6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scott TS, Zucker KA, Bailey RW. Laparoscopic cholevcystectomy: A review of 12397 patients. Surg Laparosc Endosc. 1992;2:191–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cuesta MA, Berends F, Veenhof AF. The invisible cholecystectomy: A transumbilical laparoscopic operation without a scar. Surg Endosc. 2008;212:1211–3. doi: 10.1007/s00464-007-9588-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cugura JF, Jankovic J, Kullis T, Kirac I, Beslin MB. Single incision laparoscopic surgery (SILS) cholecystectomy: Where are we. Acta Clin Croat. 2008;47:245–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Podolsky ER, Rottman SJ, Poblete H, King SA, Curcillo PG. Single port access cholecystectomy: A completely transumbilical approach. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech. 2009;19:219–22. doi: 10.1089/lap.2008.0275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Romanelli JR, Mark L, Omotosho P. Single port laparoscopic cholecystectomy with the Triport system: A case report. Surg Innov. 2008;15:223–8. doi: 10.1177/1553350608322700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Binenbaum SJ, Teixeira JA, Forrester GJ, Harvey EJ, Afthinos J, Kim GJ, et al. Single-incision laparoscopic cholecystectomy using a flexible endoscope. Arch Surg. 2009;144:734–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2009.129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]