Abstract

Median arcuate ligament (MAL) syndrome, also known as the celiac axis compression syndrome, is rare. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, characterised by the clinical triad of postprandial abdominal pain, weight loss and vomiting. Computed tomographic angiography is the gold standard for making the diagnosis of MAL and colour Doppler is essential to confirm the diagnosis. The classic management involves the surgical division of the MAL fibres. We report successful management of two patients diagnosed as MAL syndrome and treated by laparoscopic release of the MAL.

Keywords: Laparoscopic, median arcuate ligament, coeliac artery compression

INTRODUCTION

Median arcuate ligament (MAL) syndrome, also known as the celiac axis compression syndrome (CACS), was first described by Harjola in 1963.[1] It is a diagnosis of exclusion, characterised by the clinical triad of postprandial abdominal pain, weight loss and vomiting.[1–3] Several treatment options have been described in the management of CACS, including transluminal dilatation, surgical division of the MAL and arterial bypass surgery.[3] The classic management of CACS involves the surgical division of the MAL fibres.

We present two patients diagnosed to have MAL syndrome.

CASE REPORTS

Case 1

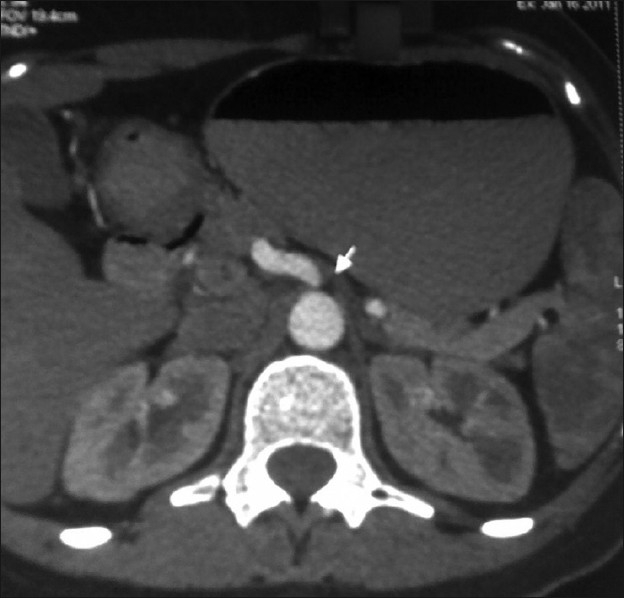

A 26-year-old housewife presented with pain in the upper abdomen, non-radiating, poorly localised since 2 months. Pain was aggravated by food. She had loose motions repeatedly since 2 months, but stool routine was normal and faecal occult blood was absent. Blood investigations and ultrasound abdomen were normal. Upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy was normal. Contrast-enhanced computerised tomography (CECT) of the abdomen was done for recurrent pain in abdomen, which showed the compression of celiac axis with post-stenotic dilatation [Figures 1 and 2].

Figure 1.

CT abdomen shows narrowing of celiac axis beyond its origin

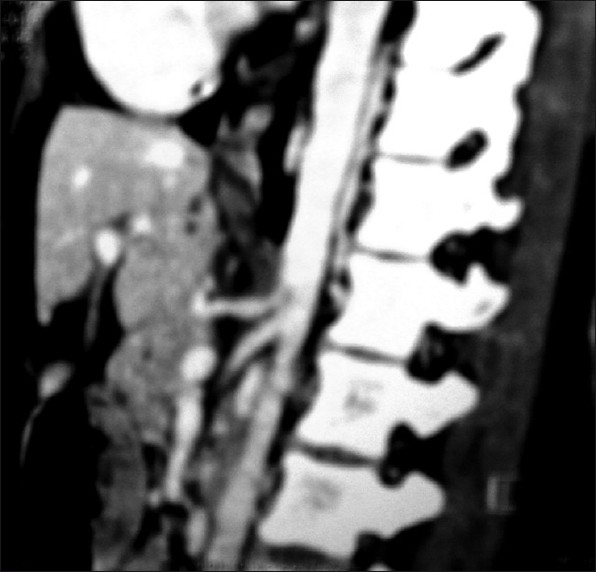

Figure 2.

CT abdomen showing indentation of its superior surface suggestive of compression due to MAL

Colour Doppler abdomen was done in supine and erect positions and in post-inspiratory and post-expiratory phases. It showed high velocities in celiac trunk in inspiration and expiration in supine position, with normal velocities in erect position classical of MALS.

Surgical technique

The patient was placed in flat lithotomy position with legs split and surgeon standing in between the legs. 10-mm camera port was placed at umbilicus by Veress needle technique. A 5-mm epigastric port was placed through which a Nathanson liver retractor was placed to lift the left lobe of the liver. Two 5-mm cannulas were introduced in the right and left upper abdomen in a manner similar to that used in a Nissen fundoplication. An additional 10-mm cannula was introduced in the left lateral abdomen. We used a 30° scope for better visualisation of the gastroesophageal junction.

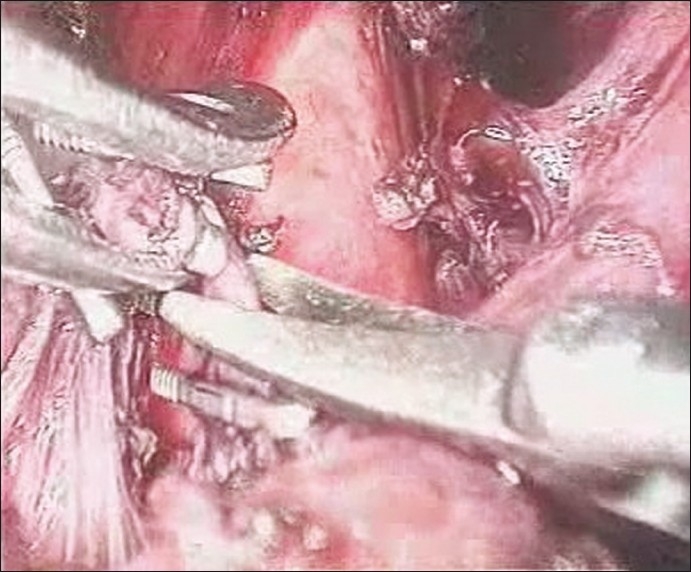

Pars flaccida was divided first, both crura dissected, oesophagus was looped with penrose drain and abdominal aorta was exposed. The dissection was started from above downward by identifying the aorta and tracing the celiac origin below. Also, the left gastric and hepatic artery dissection helped in identifying the celiac origin on the aorta. The stomach was retracted to the left to gain better exposure. Entire fibro-fatty tissue on either side of the celiac origin was removed to bare the celiac origin completely [Figures 3–5]. Once these maneuvers were completed, the celiac axis was clearly visualised without any residual kinking and uniform throughout its course. Operative time was 120 minutes and blood loss was minimal.

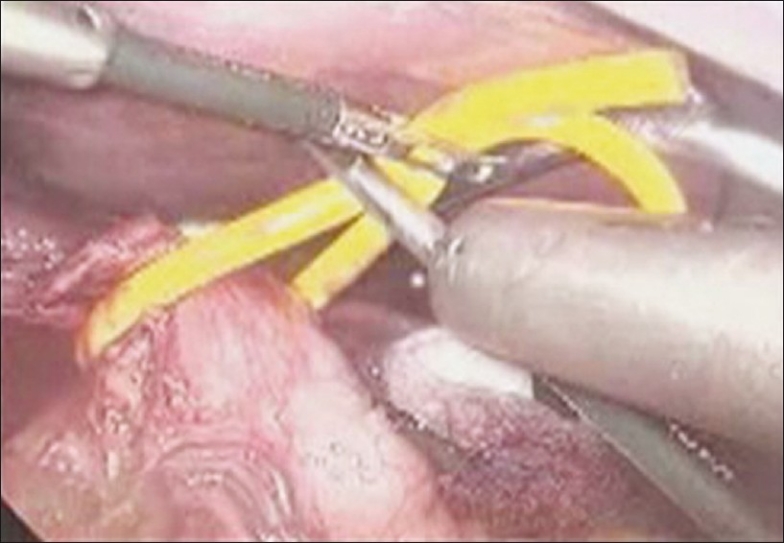

Figure 3.

Oesophagus looped

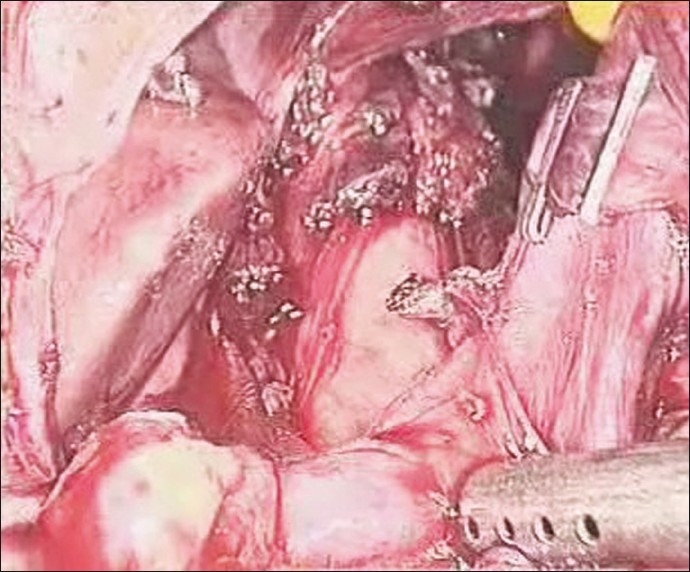

Figure 5.

Entire celiac axis bared of all fibro-fatty tissue

Figure 4.

Inferior phrenic vein clipped and cut

The postoperative period was characterised by complete relief of preoperative symptoms. Repeat Duplex ultrasound showed decreased and uniform celiac axis velocity of 145 cm/sec. The patient was discharged on postoperative day 4, and was completely symptom-free at one-, three- and 6-week follow-up visits.

Case 2

A 45-year-old widow presented with postprandial pain in upper abdomen since 3 months. All investigations were normal, except CECT abdomen which showed compression of celiac axis and post-stenotic dilatation. She underwent laparoscopic release of MAL.

Surgical technique

The dissection was started from below upward by identifying the left gastric artery and its origin to the celiac trunk was traced. This was contrary to the approach in first case. Upon further dissection, the aorta and celiac artery came into view. The fibrous attachments around the aorta and the origin of the celiac artery were carefully divided. Division of these fibres on the celiac artery was carried out circumferentially until the artery appeared to be free of any external compression.

DISCUSSION

MAL syndrome is a clinicopathologic entity. It is a diagnosis of exclusion, characterised by the clinical triad of postprandial abdominal pain, weight loss and vomiting.[1–3] An epigastric abdominal bruit can be present. Radiographic evidence of external compression of the celiac artery is needed to confirm the diagnosis, with recent reports of successful use of the computed tomographic angiography in the diagnosis of MAL.[4] The MAL normally crosses the aorta cephalad to the origin of the celiac trunk. The origin of the celiac trunk undergoes variable caudal migration in embryogenesis and may vary in location from the level of the eleventh thoracic to the first lumbar vertebra. In cases when the MAL inserts unusually low or the celiac axis is located unusually high, the MAL may compress the origin of the celiac artery.[5] With inspiration, the celiac artery descends in the abdominal cavity, resulting in a more vertical orientation of the celiac artery, which often relieves the compression.

Several studies established a correlation between syndrome suppression and decompression of the celiac trunk due to surgical sectioning of the MAL. Some authors assume that the interruption of somatic or sympathetic fibres in the course of dividing MAL may be responsible for the improvement of abdominal pain, because perivascular sympathectomy and denervation of the celiac ganglion result in increased blood flow through the celiac artery due to relief in vasospasm.

Until recently, open surgery was the mainstay therapy.[2,5] With the advent of minimally invasive surgery, increasing number of reports advocate the laparoscopic approach to CACS.[6–8] The use of intraoperative laparoscopic Doppler ultrasonography could also be helpful in confirming the adequacy of the dissection, as it allows for real-time determination of improvement in arterial flow characteristics.[6]

The technique of dissection of MAL from below upward is more beneficial, i.e., dissecting the left gastric artery and tracing its origin up to the celiac trunk than otherwise, i.e., identifying the aorta and tracing the celiac origin from above downward. From above downward, the aorta is at risk of injury which is not so in below up technique, though there is no reference in literature for either of these techniques.

The benefits of minimally invasive techniques include better visualisation of the aortic region and complete division of all the fibres of MAL and baring the celiac axis, as this is the key to successful resolution of symptoms. This also includes all the benefits of minimally invasive surgery, i.e., faster recovery and early return to diet and early discharge. The only risk is inadvertent injury to the aorta and major vessels in difficulty in controlling the bleeding.

CONCLUSIONS

Given the delicate balance between the risks and benefits in surgery for MAL syndrome, laparoscopic approach, with its superior visualisation and lack of morbidity, is the optimal treatment modality for MAL.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Harjola PT. A rare obstruction of the celiac artery: Report of a case. Ann Chir Gynaecol Fenn. 1963;52:547–50. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Reilly LM, Ammar AD, Stoney RJ, Ehrenfeld WK. Late results following operative repair for celiac artery compression syndrome. J Vasc Surg. 1985;2:79–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cina CS, Safar H. Successful treatment of recurrent celiac axis compression syndrome. A case report. Panminerva Med. 2002;44:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Horton KM, Talamini MA, Fishman EK. Median arcuate ligament syndrome: Evaluation with CT angiography. Radiographics. 2005;25:1177–82. doi: 10.1148/rg.255055001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Williams S, Gillespie P, Little JM. Celiac axis compression syndrome: Factors predicting a favorable outcome. Surgery. 1985;98:879–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Carbonell AM, Kercher KW, Heniford BT, Matthews BD. Multimedia article. Laparoscopic management of median arcuate ligament syndrome. Surg Endosc. 2005;19:729. doi: 10.1007/s00464-004-6010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Roayaie S, Jossart G, Gitlitz D, Lamparello P, Hollier L, Gagner M. Laparoscopic release of celiac artery compression syndrome facilitated by laparoscopic ultrasound scanning to confirm restoration of flow. J Vasc Surg. 2000;32:814–7. doi: 10.1067/mva.2000.107574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dordoni L, Tshomba Y, Giacomelli M, Jannello AM, Chiesa R. Celiac artery compression syndrome: Successful laparoscopic treatment-a case report. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 2002;36:317–21. doi: 10.1177/153857440203600411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]