Abstract

Background:

Anxiety disorders are common among children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. Among adults, anxiety disorder comorbidity is associated with a more severe form of bipolar disorder and a poorer outcome. There is limited data on the effect of comorbid anxiety disorder on bipolar disorder among children and adolescents.

Aim:

To study the prevalence of anxiety disorders among adolescents with remitted bipolar disorder and examine their association with the course and severity of illness, global functioning, and quality of life.

Materials and Methods:

We evaluated 46 adolescents with DSM IV bipolar disorder (I and II) who were in remission, using the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children. We measured quality of life using the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory and global functioning using the Children's Global Assessment Scale, and then compared these parameters between adolescents with and without current anxiety disorders. We also compared the two groups on other indicators of severity such as number of episodes, suicidal ideation, presence of psychotic symptoms, and response to treatment.

Results:

Among the 46 subjects, the prevalence of current and lifetime anxiety disorders were 28% (n=13) and 41% (n=19), respectively. Compared with others, adolescents with anxiety had more lifetime suicidal ideation, more number of episodes, lower physical, psychosocial, and total subjective quality of life, and lower global functioning.

Conclusions:

Among adolescents with bipolar disorder, anxiety disorders are associated with a poorer course, lower quality of life, and global functioning. In these subjects, anxiety disorders should be promptly recognized and treated.

Keywords: Adolescents, anxiety disorders, bipolar disorder, outcome, quality of life, severity

INTRODUCTION

Anxiety disorders are common among adults with bipolar disorder and influence their clinical and functional outcome.[1,2] In adults, they are associated with greater severity, earlier age-at-onset, mixed state presentations, poor symptomatic and functional recovery, suicidal behavior, diminished acute response to pharmacological treatment, decreased quality of life, and unfavorable course and outcome.[3,4]

Although the consequences of anxiety disorders comorbidity among adults are well elucidated, the data are inconclusive among children and adolescents.[5–9] Drug-induced hypomania was more common among children with anxiety disorders (30-36%), than those without comorbid anxiety disorders (22%).[8] In one study, those adolescents with anxiety had a lower age at onset and more hospitalizations than those without.[5] A later study has suggested that adolescents with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and comorbid bipolar disorder are more likely to have a substance use disorder compared with those who did not have PTSD.[9] Studies that have compared the illness severity among children and adolescents with or without anxiety disorders using the Clinical Global Impression severity scale have been inconsistent in their findings.[6,8] In two studies, presence of anxiety disorders had no influence on global functioning.[5,6] The studies that have determined the association of anxiety with outcomes among children and adolescents with bipolar disorder have two main limitations. First, they do not provide enough information regarding illness severity and quality of life of these children and adolescents. Second, they assessed study subjects during affective episodes. Anxiety symptoms may occur exclusively during mood episodes[10–13] and hence, the assessment of anxiety during mood episodes may result in overestimation of the prevalence of anxiety disorders. Only one study estimated the prevalence of anxiety disorders in remission.[14] However, remission from mood episodes was determined historically without a clear assessment of the same.

The study of the impact of anxiety disorder comorbidity among children and adolescents with bipolar disorder may have clinical and theoretical implications. Clinically, the presence of anxiety disorders may alter the pharmacotherapeutic choices, especially considering the higher rate of antidepressant-associated hypomania.[8] From the perspective of understanding the heterogeneity of bipolar disorders, it is possible that those subjects with bipolar and anxiety disorders may have a different subtype of bipolar disorder.[15]

In this study, we report the prevalence of anxiety disorders among adolescents with remitted bipolar disorder and their association with the course and severity of illness, global functioning, and quality of life. We hypothesized that adolescents with anxiety disorders would have a more severe course of bipolar disorder, poorer quality of life, and lower global functioning.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The ethics committee of the institute approved the study. Parents of the subjects gave written informed consent and consent was taken from the adolescents themselves, before participating in the study.

Subjects

We screened the clinical records of adolescents with bipolar disorder registered with the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (CAP) services of the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (NIMHANS) hospital, Bangalore, India, between October 01, 2004 and November 30, 2006 for possible inclusion in the study. Those aged between 12 and 16 years (both inclusive) with a primary diagnosis of DSM IV[16] bipolar disorder I or II, in remission, were included in the study. Clinical remission was determined as (a) the Childhood Depression Rating Scale score less than 29[17] and (b) the Young's Mania Rating Scale-(Parent and Child version) score less than 8.[18] We excluded children with mental retardation, pervasive developmental disorders, schizophrenia, organic affective disorder, and bipolar disorder NOS.

Of the 113 subjects who were registered for treatment of bipolar disorder, 47 (42%) did not meet inclusion criteria: 33 subjects had mental retardation, one had pervasive developmental disorder, three had organic affective disorder, and 10 had a clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder but did not meet criteria for DSM IV bipolar disorder I or II. Of the remaining 66 eligible subjects, 46 (63%) were then evaluated in detail. Subjects who were evaluated (n=46) did not differ from those who could not be evaluated (n=20), with respect to age, gender, income, residential status (urban vs rural), age at onset of illness, duration of illness at presentation, and polarity of the index episode. However, interviewed subjects had more number of episodes at initial presentation (median [range]: 2 [1-6] vs 1 [1-4]; P=0.028). Twenty subjects could not be evaluated because they did not come for assessment despite our best efforts to contact them.

Assessments

A clinical diagnosis of bipolar disorder had been made by a senior child and adolescent psychiatrist of the CAP unit after reviewing the information obtained by a postgraduate trainee and interviewing the adolescent and the parent (s). The principal author reconfirmed the diagnosis by administering the Schedule for Affective disorders and Schizophrenia for School age Children-Present and Lifetime version (K-SADS-PL).[19] The K-SADS-PL is a semi-structured diagnostic interview designed to assess current and past episodes of psychopathology in children and adolescents according to DSM-IV criteria. The reliability of this instrument has been reported to be kappa=0.92.[20] The K-SADS-PL was used to confirm diagnosis of bipolar disorder and to diagnose anxiety disorders and other comorbid disorders such as disruptive behavior disorders.

A life chart was drawn based on the data gathered during interview and from supplemental information from the case records.[21] We assessed the subjective quality of life with the pediatric quality of life inventory (Peds QL)[22] and the global functioning using the Children's Global Assessment Scale (CGAS).[23] The Peds QL is a modular instrument measuring the health-related quality of life of children and adolescents with acute and chronic health conditions. This tool has been used in child psychiatric conditions including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder[24] and developmental disorder,[25] and has a reliability of kappa=0.88-0.90.[22] CGAS is an instrument that provides a global measure of level of functioning among children and adolescents, with its reliability reported to be kappa=0.61.[26]

We used the data from the interviews and the clinical records to assess predetermined indices of severity of illness that included response to maintenance treatment, suicidal ideation, psychotic symptoms, and proportion of time spent in episodes.

Operational definitions

We defined good response to maintenance treatment[3,27] as (a) decrease in frequency and severity of episodes with treatment (objectively and subjectively maintaining improvement over the duration of treatment), OR (b) no relapses while on treatment, OR (c) a relapse following discontinuation of treatment. Chronic course was defined as an episode lasting 12 months or more.[20] We defined adequate compliance to mood stabilizers as the absence of history of drug default or dose reduction by the patients themselves based on the treatment history obtained during interview and from the clinical case record. All subjects with bipolar disorder had been recommended maintenance treatment with mood stabilizers.

Statistical analysis

We used Chi-square test/Fisher's exact test for categorical variables, unpaired t test for normally distributed continuous variables, and Mann Whitney U test for non-normally distributed continuous variables. Normality was tested using Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. We examined associations between anxiety disorders and indices of severity, course, quality of life, and global functioning using binary logistic regressions for categorical (good response to treatment, presence of suicidal ideation, and presence of psychotic symptoms) and linear regressions for continuous variables (quality of life, percentage of duration of illness spent in episodes, and global functioning), respectively. We performed linear regressions for the continuous variables as they were normally distributed. For linear regressions, discontinuous variables were used as indicator variables. The regression analyses were performed after controlling for the possible confounding effects of age, age at onset of bipolar disorder, gender, duration of illness, number of episodes, number of depressive episodes, and polarity of the most recent episode. All statistical analyses were performed using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) Version: 13.0. The correction for planned group comparisons was made using a domain-wise Bonferroni adjusted P value.[28,29] With five domains (demographic characteristics, illness course, illness severity, global functioning, and quality of life), the P value required for significance was 0.01 (0.05/5).

RESULTS

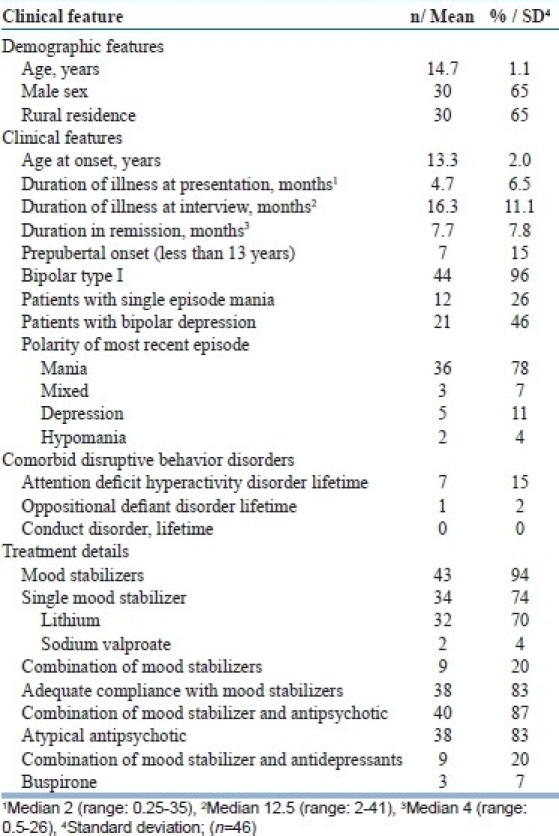

Demographic, clinical, and treatment characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the 46 adolescents, most were boys residing in a rural area and many had dropped out from school. Most (96%) had bipolar I disorder and had an adolescent onset. Rates of comorbid disruptive behavior disorders were very low. Chronicity or rapid cycling was uncommon (7%). The most recent episode was mania in most of the adolescents. A majority were treated with mood stabilizers, mostly with lithium and often in combination with atypical antipsychotic drugs. Antidepressants were used in nine (20%) subjects for the treatment of either depressive episodes or anxiety disorders. Overall, the adolescents interviewed were good responders to maintenance treatment (n=38, 83%).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of the adolescents

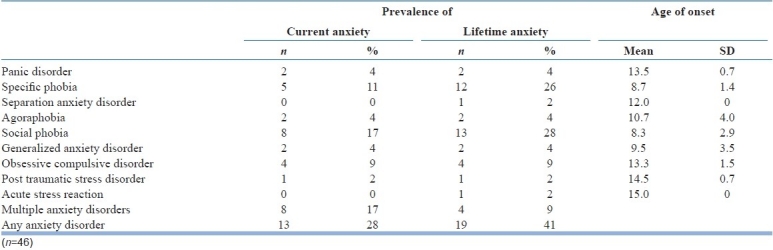

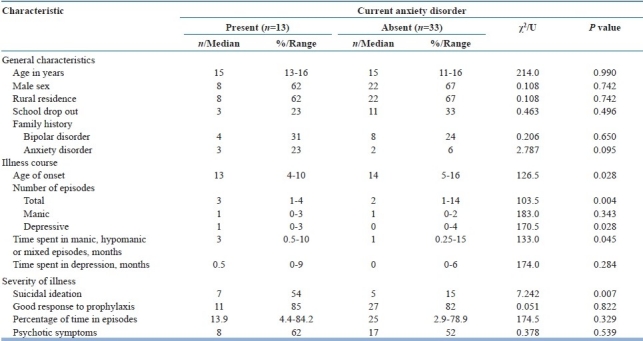

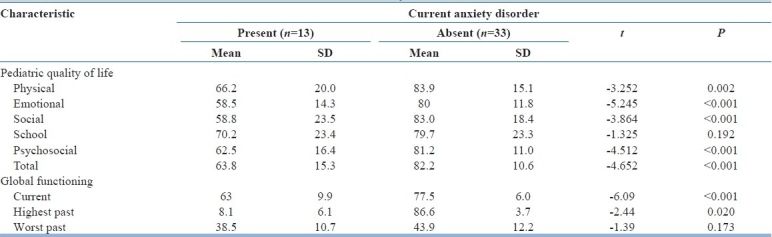

Nineteen subjects (41%) had had an anxiety disorder sometime during their life and 13 (28%) had an anxiety disorder diagnosis at the time of assessment [Table 2]. In a majority (n=17, 90%), anxiety disorder predated the onset of bipolar disorder. Comparison of clinical features in those with and without current anxiety is shown in Table 3. Those with a current anxiety disorder were comparable with those without, with respect to demographic features, schooling and family history, but had more number of episodes and greater suicidal ideation. Those with anxiety also had a trend toward an earlier age of onset, more depressive episodes, and more time being spent in manic, hypomanic, or mixed episodes. Subjects with current anxiety disorders also had poorer physical, emotional, social, and psychosocial quality of life and a lower level of global functioning [Table 4].

Table 2.

Prevalence and age of onset of anxiety among adolescents with bipolar disorders

Table 3.

Comparison of clinical features among adolescents with bipolar disorders with and without current anxiety disorder

Table 4.

Comparison of quality of life and global functioning among adolescents with and without current anxiety disorder

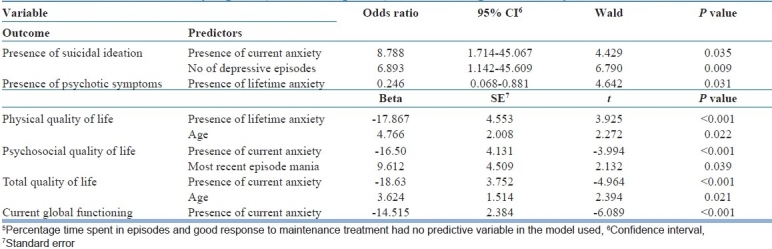

It is evident from the regression analysis that comorbid anxiety disorders was associated with presence of lifetime suicidal ideation and more number of mood episodes; lower physical, psychosocial, and total subjective quality of life; and lower global functioning [Table 5]. The adolescents’ response to maintenance treatment and the proportion of time spent in episodes were not predicted by any of the variables used in the model.

Table 5.

Binary logistic (forward step-wise) and linear regression analyses of outcome[5]

DISCUSSION

Among adolescents with predominantly type I bipolar disorder, almost one-third had a current anxiety disorder and less than half had had at least one anxiety disorder sometime during their life. Subjects with one or more anxiety disorders at the time of assessment were more likely to have had suicidal ideation, had a poorer quality of life, and had lower global functioning compared with those without an anxiety disorder.

Our study has several methodological merits. We studied anxiety disorders in subjects remitted from affective episodes. This may have decreased the confounding effect of mood symptoms on the assessment of anxiety disorders. A trained psychiatrist administered all instruments on direct interview with subjects and at least one parent, using a valid and reliable semi-structured interview schedule. We measured the subjective quality of life, an often ignored, but important outcome measure among adolescents with bipolar and anxiety disorders.

Prevalence of anxiety disorders

We estimated the prevalence of current anxiety during periods of remission. Lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders in the only other study in which remission from affective episodes was considered a requisite for the diagnoses of anxiety disorders was 18%,[14] a rate much lower than that reported in our study (41%). The lifetime prevalence of anxiety in our study, however, is lower than that reported in other studies (53-76%) of clinic-based populations.[6,20,30,31] The subjects in these studies had predominantly prepubertal onset (mean, 3.9-10.5 years) with high rates of disruptive behavior disorders (39-95%) and chronicity (70-83%). In contrast, our subjects mostly had adolescent onset illness with a low rate of disruptive behavior disorders (15%) and chronic course (7%). The differing sample characteristics may have contributed to the varying rates of anxiety disorders across studies. Low prevalence of disruptive disorders in our sample is consistent with the rates reported in previous studies from our center,[32–34] although it is not clear why the rates of disruptive behavior disorders in our samples are much lower than in the samples from USA and Europe. The prevalence of anxiety disorders in our study, however, is comparable with the lifetime anxiety rate of 33% reported in a community-based study.[35] Nonetheless, there is a possibility that we may have overestimated the lifetime prevalence of anxiety disorders because patients and relatives may have had problems in recalling whether past anxiety symptoms were part of mood episode or not.

Impact of anxiety disorders on the course and severity of bipolar disorder

Adolescents with anxiety disorders had a greater number of episodes, depressive episodes in particular, and a higher lifetime suicidal ideation, suggesting that comorbid anxiety is associated with a more severe course of bipolar disorder. Anxiety has been associated with poorer syndromal recovery in one,[36] but not in the other follow-up studies of bipolar disorder among children and adolescents.[32,37] A study of adults with bipolar disorder in remission from our center reported a greater severity of bipolar disorder in the anxious subgroup.[3] Studies among adults with bipolar disorder report greater number of episodes[38] and higher suicidal ideation[4] among those with anxiety. These findings suggest that anxiety disorders maybe associated with a more severe form of bipolar disorder.

Our sample had a shorter duration of illness at the time of assessment (median, 12.5 months) and this coupled with a relatively smaller sample size may have resulted in failure to identify differences with respect to certain course/severity measures such as time spent in episodes and response to maintenance treatment. It is possible that anxious bipolar subjects spend a longer time in episodes and have a poorer response to maintenance treatment as has been reported in adult bipolar subjects with comorbid anxiety.[1] A longer follow-up of a larger sample may identify further differences in course between anxious and nonanxious bipolar adolescents.

Among adults, anxiety symptoms and disorders are associated with a higher prevalence of suicidality.[4,39] There is paucity of data regarding the association between comorbid anxiety, depressive episodes, and suicidal ideation among children and adolescents with bipolar disorder. However, previous epidemiological studies of major depressive disorder reported a high prevalence of anxiety disorders (38 to 72%) among depressed children and adolescents indicating a strong association between depression and anxiety.[40] It is possible that comorbid anxiety disorders predispose to depression and suicidality among children and adolescents with bipolar disorder.

Influence of anxiety on functioning and quality of life

Anxiety was associated with a poorer quality of life and lower global functioning. This association remained significant when adjusted for other variables in the regression analyses. School-related quality of life was not different across anxious and nonanxious groups, possibly due to the high dropout rate and the reliance of the items on school attendance and performance. Our results differed from one study that reported no association between global functioning and presence of panic disorder in bipolar youths.[6] However, this study may not be fully comparable with ours as it only examined panic disorder, the prevalence of which was low in our study.

Implications

The observed bipolar-anxiety comorbidity and its association with poorer quality of life, lower global functioning, and somewhat more severe course highlight the need for recognition and treatment of anxiety disorders. Clinicians have to specifically enquire for symptoms of anxiety disorders routinely in the process of evaluation of young individuals with bipolar disorder, preferably with a structured interview schedule. Anxiety disorders are often ignored in the process of evaluation of bipolar disorders because of the traditional hierarchical method of diagnosis where anxiety symptoms are considered part of the primary diagnosis.

A comorbid diagnosis of an anxiety disorder leads to the difficult issue of management. Antidepressants effective in treating anxiety disorders can cause hypomanic/manic switch. A recent review suggested that switch rates are not unusually high with SSRIs.[41] However, there remain concerns about not only their ability to cause a switch, but also their association with cycle acceleration.[42,43] In routine clinical practice, patients with anxiety disorders are often prescribed antidepressants under the cover of mood stabilizers. It remains to be examined whether it is safe to prescribe antidepressants or consider alternative treatment options such as cognitive behavior therapy.

The exact nature of relationship between anxiety disorders comorbidity and bipolar disorder is unclear. In a majority of our subjects, anxiety disorders had an earlier age of onset than bipolar disorder. The impact of anxiety disorders on illness severity and the associated functional measures suggest that anxiety may be an indicator of a more severe bipolar subtype among adolescents. It is also possible that anxiety disorders are potential early markers for bipolar disorder in a subset of patients.[44] Alternatively, anxiety disorders and bipolar disorders may share an associated biology or genetic risk.[45] Further research into the biological and genetic correlates and treatment responses of anxious subjects with bipolar disorder may be necessary to explain the nature of this association. In addition, longitudinal studies may provide information on the sequence of onset and the impact of anxiety on the outcome of bipolar disorder.

Limitations

Our results have to be interpreted in the light of certain limitations. First, the study was cross-sectional; therefore, assessment of the course is open to recall bias. Second, the sample was relatively small and from a hospital-based population. Third, we did not include subjects with bipolar disorder not otherwise specified (NOS). A recent study provided evidence supporting the validity of diagnosis of bipolar disorder NOS among children and adolescents.[37] Fourth, the K-SADS-PL and the scale for measurement of quality of life have not been validated in the Indian population. Finally, the interviewer who measured the global functioning was not blind to the anxiety disorder diagnoses of the adolescents.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study has demonstrated that anxiety disorders are not only common comorbid conditions in adolescents with bipolar disorder, but are also associated with an earlier age of onset, somewhat severe course, poorer quality of life, and lower global functioning. Although our findings do not establish direct cause and effect relationship between anxiety disorders and poor outcome, there is a need for recognition and treatment of anxiety disorders among young people with bipolar disorder because it may perhaps improve outcome. Future studies should examine the impact of anxiety disorders on the long-term outcome of bipolar disorder prospectively. More importantly, treatment studies of bipolar disorder should specifically examine the impact of various comorbid disorders including anxiety disorders on treatment response and outcome.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.McIntyre RS, Soczynska JK, Bottas A, Bordbar K, Konarski JZ, Kennedy SH. Anxiety disorders and bipolar disorder: A review. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:665–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Albert U, Rosso G, Maina G, Bogetto F. Impact of anxiety disorder comorbidity on quality of life in euthymic bipolar disorder patients: Differences between bipolar I and II subtypes. J Affect Disord. 2008;105:297–303. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.05.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zutshi A, Reddy YC, Thennarasu K, Chandrashekhar CR. Comorbidity of anxiety disorders in patients with remitted bipolar disorder. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:428–36. doi: 10.1007/s00406-006-0658-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Simon NM, Otto MW, Wisniewski SR, Fossey M, Sagduyu K, Frank E, et al. Anxiety disorder comorbidity in bipolar disorder patients: Data from the first 500 participants in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2222–9. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.12.2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dickstein DP, Rich BA, Binstock AB, Pradella AG, Towbin KE, Pine DS, et al. Comorbid anxiety in phenotypes of pediatric bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2005;15:534–48. doi: 10.1089/cap.2005.15.534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Masi G, Perugi G, Millepiedi S, Toni C, Mucci M, Bertini N, et al. Clinical and research implications of panic-bipolar comorbidity in children and adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2007;153:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2006.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masi G, Perugi G, Toni C, Millepiedi S, Mucci M, Bertini N, et al. Obsessive-compulsive bipolar comorbidity: Focus on children and adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2004;78:175–83. doi: 10.1016/S0165-0327(03)00107-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Masi G, Toni C, Perugi G, Mucci M, Millepiedi S, Akiskal HS. Anxiety disorders in children and adolescents with bipolar disorder: A neglected comorbidity. Can J Psychiatry. 2001;46:797–802. doi: 10.1177/070674370104600902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinbuchel PH, Wilens TE, Adamson JJ, Sgambati S. Posttraumatic stress disorder and substance use disorder in adolescent bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:198–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2008.00652.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feske U, Frank E, Mallinger AG, Houck PR, Fagiolini A, Shear MK, et al. Anxiety as a correlate of response to the acute treatment of bipolar I disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:956–62. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.6.956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Young LT, Cooke RG, Robb JC, Levitt AJ, Joffe RT. Anxious and non-anxious bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 1993;29:49–52. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(93)90118-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Joffe RT, Bagby RM, Levitt A. Anxious and nonanxious depression. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1257–8. doi: 10.1176/ajp.150.8.1257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Swartz CM, Shen WW. Is episodic obsessive compulsive disorder bipolar? A report of four cases. J Affect Disord. 1999;56:61–6. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(99)00021-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Findling RL, Gracious BL, McNamara NK, Youngstrom EA, Demeter CA, Branicky LA, et al. Rapid, continuous cycling and psychiatric co-morbidity in pediatric bipolar I disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2001;3:202–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Freeman MP, Freeman SA, McElroy SL. The comorbidity of bipolar and anxiety disorders: Prevalence, psychobiology, and treatment issues. J Affect Disord. 2002;68:1–23. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0327(00)00299-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. Revised 4th ed. Washington DC: American Psychiatric Press; 2000. American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Poznanski EO, Grossman JA, Buchsbaum Y, Banegas M, Freeman L, Gibbons R. Preliminary studies of the reliability and validity of the children's depression rating scale. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1984;23:191–7. doi: 10.1097/00004583-198403000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ketter TA, Jones M, Paulsson B. Rates of remission/euthymia with quetiapine monotherapy compared with placebo in patients with acute mania. J Affect Disord. 2007;100:S45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2007.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, et al. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (K-SADS-PL): Initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–8. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Biederman J, Faraone SV, Wozniak J, Mick E, Kwon A, Cayton GA, et al. Clinical correlates of bipolar disorder in a large, referred sample of children and adolescents. J Psychiatr Res. 2005;39:611–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2004.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Post RM, Denicoff KD, Leverich GS, Altshuler LL, Frye MA, Suppes TM, et al. Morbidity in 258 bipolar outpatients followed for 1 year with daily prospective ratings on the NIMH life chart method. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:680–90. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v64n0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varni JW, Seid M, Rode CA. The PedsQL: Measurement model for the pediatric quality of life inventory. Med Care. 1999;37:126–39. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199902000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shaffer D, Gould MS, Brasic J, Ambrosini P, Fisher P, Bird H, et al. A children's global assessment scale (CGAS) Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1983;40:1228–31. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1983.01790100074010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Varni JW, Burwinkle TM. The PedsQL as a patient-reported outcome in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: A population-based study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2006;4:26. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-4-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lau KM, Chow SM, Lo SK. Parents’ perception of the quality of life of preschool children at risk or having developmental disabilities. Qual Life Res. 2006;15:1133–41. doi: 10.1007/s11136-006-0067-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hanssen-Bauer K, Gowers S, Aalen OO, Bilenberg N, Brann P, Garralda E, et al. Cross-national reliability of clinician-rated outcome measures in child and adolescent mental health services. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2007;34:513–8. doi: 10.1007/s10488-007-0135-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henry C, Van den Bulke D, Bellivier F, Etain B, Rouillon F, Leboyer M. Anxiety disorders in 318 bipolar patients: Prevalence and impact on illness severity and response to mood stabilizer. J Clin Psychiatry. 2003;64:331–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rao NP, Reddy YC, Kumar KJ, Kandavel T, Chandrashekar CR. Are neuropsychological deficits trait markers in OCD? Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:1574–9. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2008.05.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Purcell R, Maruff P, Kyrios M, Pantelis C. Neuropsychological deficits in obsessive-compulsive disorder: A comparison with unipolar depression, panic disorder, and normal controls. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:415–23. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.5.415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Harpold TL, Wozniak J, Kwon A, Gilbert J, Wood J, Smith L, et al. Examining the association between pediatric bipolar disorder and anxiety disorders in psychiatrically referred children and adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2005;88:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2005.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wilens TE, Biederman J, Forkner P, Ditterline J, Morris M, Moore H, et al. Patterns of comorbidity and dysfunction in clinically referred preschool and school-age children with bipolar disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharmacol. 2003;13:495–505. doi: 10.1089/104454603322724887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jairam R, Srinath S, Girimaji SC, Seshadri SP. A prospective 4-5 year follow-up of juvenile onset bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2004;6:386–94. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2004.00149.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jaideep T, Reddy YC, Srinath S. Comorbidity of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in juvenile bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2006;8:182–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2006.00293.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reddy YC, Srinath S. Juvenile bipolar disorder. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;102:162–70. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2000.102003162.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewinsohn PM, Klein DN, Seeley JR. Bipolar disorders in a community sample of older adolescents: Prevalence, phenomenology, comorbidity, and course. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1995;34:454–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.DelBello MP, Hanseman D, Adler CM, Fleck DE, Strakowski SM. Twelve-month outcome of adolescents with bipolar disorder following first hospitalization for a manic or mixed episode. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:582–90. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2007.164.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Birmaher B, Axelson D, Strober M, Gill MK, Valeri S, Chiappetta L, et al. Clinical course of children and adolescents with bipolar spectrum disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:175–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.2.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tamam L, Ozpoyraz N. Comorbidity of anxiety disorder among patients with bipolar I disorder in remission. Psychopathology. 2002;35:203–9. doi: 10.1159/000063824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bauer MS, Altshuler L, Evans DR, Beresford T, Williford WO, Hauger R. Prevalence and distinct correlates of anxiety, substance, and combined comorbidity in a multi-site public sector sample with bipolar disorder. J Affect Disord. 2005;85:301–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2004.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williamson DE, Forbes EE, Dahl RE, Ryan ND. A genetic epidemiologic perspective on comorbidity of depression and anxiety. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 2005;14:707–26. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2005.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Gijsman HJ, Geddes JR, Rendell JM, Nolen WA, Goodwin GM. Antidepressants for bipolar depression: A systematic review of randomized, controlled trials. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1537–47. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.9.1537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ghaemi SN. Treatment of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: Are antidepressants mood destabilizers? Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:300–2. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.07121931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schneck CD, Miklowitz DJ, Miyahara S, Araga M, Wisniewski S, Gyulai L, et al. The prospective course of rapid-cycling bipolar disorder: Findings from the STEP-BD. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:370–7. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.05081484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Johnson JG, Cohen P, Brook JS. Associations between bipolar disorder and other psychiatric disorders during adolescence and early adulthood: A community-based longitudinal investigation. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:1679–81. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.10.1679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Jolin EM, Weller EB, Weller RA. Anxiety symptoms and syndromes in bipolar children and adolescents. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2008;10:123–9. doi: 10.1007/s11920-008-0022-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]