Abstract

Context:

Longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) is known to be associated with poorer outcome of schizophrenia. DUP is also known to be longer in lower- and middle-income countries. Methodologically sound studies that have examined the association of DUP and outcome of schizophrenia in these countries are lacking.

Aim:

The aim was to evaluate the association between DUP and outcome of never-treated schizophrenia patients.

Setting and Design:

This study was conducted at the National Institute of Mental Health and Neurosciences, Bangalore, using a prospective cohort design.

Materials and Methods:

119 patients with schizophrenia/schizophreniform disorder diagnosed using the computerized diagnostic interview schedule for DSM-IV (CDIS-IV) were further assessed for DUP with the interview for retrospective assessment of onset of schizophrenia (IRAOS). After a mean (SD) follow-up period of 55.9 (37.2) weeks, the social and occupational functioning and psychopathology of 93 (80.2% of the surviving patients) patients were assessed using the social and occupational functioning scale (SOFS) and the positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS), by raters blind to the DUP data. Spearman's correlation and Kendall's tau-B test were used to analyze the relationship between DUP and the outcome variables.

Results:

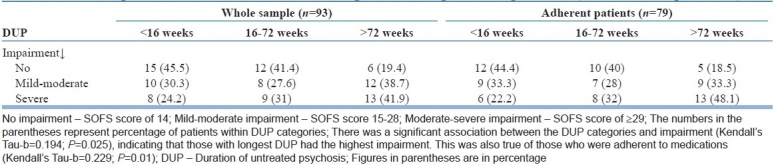

The mean DUP was 90.2 (median=30.1; SD=121.9) weeks. SOFS and PANSS scores at follow-up were statistically significantly associated with DUP, but not with other baseline variables (SOFS: rho=0.22, P=0.03; PANSS: rho=0.23, P=0.03). Among those with the shortest DUP (<16 weeks; n=33), 45.5%, 30.3%, and 24.2% had no impairment, mild-moderate impairment, and severe impairment, respectively. In contrast, 19.4%, 38.7%, and 41.9% of those with the longest DUP (>72 weeks; n=31) had no, mild-moderate, and severe impairment, respectively (Kendall's Tau-b=0.194; P=0.025).

Conclusions:

The delay in accessing treatment among patients with psychosis is considerable in India, a lower- to middle-income country. Longer DUP is associated with poorer psychopathological and functional outcomes in persons with schizophrenia/schizophreniform disorder.

Keywords: Duration of untreated psychosis, low- and middle-income countries, outcome, schizophrenia

INTRODUCTION

Research has consistently shown that longer duration of untreated psychosis (DUP) is associated with poorer outcomes among persons with schizophrenia.[1,2] Although the course of schizophrenia differs across countries, patients from low- and middle-income (LAMI) countries are reported to have better outcomes.[3,4] This result is surprising, given that mental healthcare delivery systems are poorer in the LAMI countries[5] and the average DUP tends to be longer in these countries.[6]

There is a need to examine the relationship between DUP and schizophrenia outcomes in LAMI countries. However, research is sparse in this aspect. Recently, Farooq and colleagues[7] reviewed the available research examining the association of DUP and outcome of schizophrenia in LAMI countries including India.[8,9] Though their meta-analysis suggested that delay in the initiation of treatment for psychosis and increased levels of DUP is associated with a poorer response to treatment and outcome in LAMI countries, the authors pointed out that these studies did not meet quality criteria suggested by Marshall and colleagues.[2] The criteria suggest that (a) participants be diagnosed according to the accepted standardized diagnostic criteria, (b) outcomes should be assessed blind to DUP status, (c) follow-up rates be at least 80%, and (d) there are standardized methods to determine DUP. Thus, the relationship between DUP and outcome in LAMI countries has remained equivocal. In this background, the aim of the article is to describe the results of a 1-year follow-up study, which meets all the quality criteria described above.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Patients

Consecutive patients attending one adult psychiatry unit's outpatient services of the national institute of mental health and neurosciences (NIMHANS), Bangalore, were recruited if they fulfilled the criteria for schizophrenia or schizophreniform disorder and had never received antipsychotic medications. The first author used the computerized diagnostic interview schedule for DSM-IV (CDIS-IV)[10] to confirm the diagnosis. Those with comorbid psychiatric diagnoses, including substance use disorders (except nicotine), organic brain disorder, and mental retardation were excluded.

Assessments

Assessments were chosen to evaluate how DUP affected social functioning and psychopathology at 1-year follow-up.

Duration of untreated psychosis

The interview for retrospective assessment of onset of schizophrenia (IRAOS)[11] was used to assess the onset of schizophrenia symptoms and the disorder. The IRAOS assesses the onset of psychotic and non-psychotic symptoms of schizophrenia in detail. The IRAOS was modified to suit the Indian context; a trained rater (RS; see Acknowledgments) used it to assess DUP. This tool has been used in an earlier study conducted in South India.[12] DUP was defined as the time since the onset of the first psychotic symptom to the time of the interview. Some of the patients (n=21) were also clinically evaluated by a resident doctor BM Veena and the data regarding the DUP as clinically assessed by the resident doctor had excellent concordance with DUP as established by IRAOS, with an intra-class correlation coefficient of 0.95 (P<0.001).

Symptoms

The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS)[13] was used to assess the severity of symptoms at both baseline and regular intervals at each follow-up (see text under the section “Treatment and follow-up”). For the purpose of this paper, PANSS rating at the 1-year follow-up point (when their social functioning was also assessed) was examined. The raters were trained in the use of PANSS using training videos. The inter-rater reliability was assessed between them for the subscores and total score of PANSS of eight patients who were not included in the study. Reliability was found to be excellent, with an intra-class correlation of 0.92 (P<0.001).

Social and occupational functioning

Functional outcome after 1 year was assessed using the social and occupational functioning scale (SOFS),[14] a scale specifically validated for assessing the level of functioning of schizophrenia patients in India. SOFS assesses patients’ functioning across 14 domains, including self-care, conversational skills, work, money management, etc., on a scale of 1 (no impairment) to 5 (extreme impairment). While administering the SOFS, both patients and their close family members were interviewed together for rating patients’ level of functioning. The SOFS was administered by the first author, who was blind to the DUP data. The rater achieved excellent inter-rater reliability in total SOFS score with another independent rater (33 patients; intra-class correlation=0.94; P<0.001). The mean (SD) interval between the recruitment and SOFS rating was 55.9 (37.2) weeks.

Treatment and follow-up

Patients received the following antipsychotics after their initial evaluation and through the follow-up period: risperidone (n=99), olanzapine (n=11), fluphenazine depot injections (n=7), chlorpromazine (n=2), haloperidol (n=2), and flupenthixol depot injections (n=2). All patients and their family members went through an hour-long psychoeducation session, which covered topics of causes, clinical features, course, and treatment of schizophrenia. At each clinical follow-up, which ranged from once in 2 months to once in 4 months, adherence to prescribed medication was checked. The information regarding this was collected both from the patient as well as from the caregivers who lived with the patient and supervised their medications. The SOFS could be administered reliably in 93 patients at the 1-year follow-up (i.e., they came with reliable family caregivers). Five patients came for follow-up visits without reliable caregivers, and thus we were unable to obtain SOFS data from them. A project social worker attempted home visits in the 21 remaining patients. Among the 11 patients contacted during home visits, one was symptomatic and the rest were symptom-free. None was interested in visiting the hospital. The visiting social worker was not trained on the use of the SOFS. Three patients had died: one from suicide. Seven patients were not traceable despite all efforts.

Statistical analysis

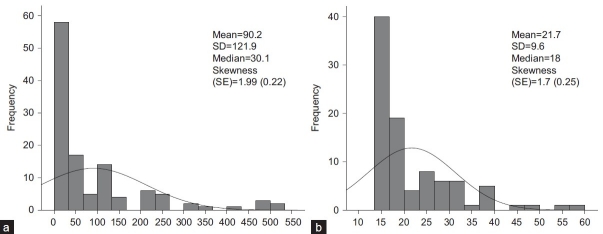

All variables were tested for normality of distribution. As DUP and functional impairment scores were not normally distributed [Figure 1], non-parametric tests were used while analyzing their association.[15] To examine the relationship between continuous variables, Spearman's correlation was used; Kendall's tau-b statistic was used to assess the association between ranked categories of DUP and functional impairment. In order to avoid the confounding effects of variable medication adherence on the outcome, separate analyses were conducted for those who had a minimum of 80% adherence.

Figure 1.

(a) Distribution of duration of untreated psychosis in weeks and (b) Social and occupational functioning scale total score

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the NIMHANS ethical committee. The subjects were recruited after obtaining the written informed consent from them as well as their guardians.

RESULTS

One hundred and nineteen patients [mean (SD) age=30.5 (8.8) years; females=55 (46.2%)] meeting these criteria were recruited between September 2005 and March 2006. Treatment adherence was assessed in 93 patients in whom the SOFS could be administered, as mentioned already. The adherence rates were as follows: 79 (84.9%) patients were adherent for 80-100% of the follow-up period, 4 (4.3%) patients for 60-79% of the period, 2 (2.2%) patients for 40-59% of the period, 2 (2.2%) patients for 20-39% of the period, and 6 (6.5%) patients for less than 20% of the period.

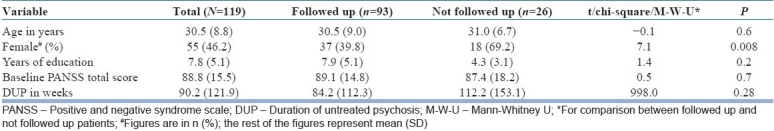

Baseline

Table 1 shows the comparison of patients who were followed up (n=93) and those who were not (n=26). There was no difference between the two with respect to any other variables except gender: females were significantly less likely to be followed up. DUP was positively correlated with the severity of symptoms at the baseline: Spearman's rho for correlation between DUP and PANSS total score at the baseline was 0.25 (n=119; P<0.01) for the entire sample and 0.23 (n=93; P=0.03) for the followed-up patients.

Table 1.

Comparison between followed up and not followed up patients

Symptomatic and functional outcome

The SOFS total score also had a positively skewed distribution [Figure 1]. It had a significant positive correlation with DUP (n=93; rho=0.22; P=0.03). Further, PANSS total score at the time of follow-up had a positive correlation with DUP (n=93; rho=0.23; P=0.03). A separate analysis was conducted for those who were adherent for at least 80% of the follow-up period (n=79). Specifically, social functioning and psychopathology at the end of 1-year follow-up was examined for its relationship to DUP: the correlation between SOFS total score and DUP was statistically significant (n=79; rho=0.24; n=0.03), as was the correlation between psychopathology and DUP (n=78; rho=0.27; P=0.02). SOFS and PANSS scores had no significant correlation with age (PANSS: rho=–0.007, P=0.95; SOFS: rho=–0.20, P=0.08), years of education (PANSS: rho=–0.19, P=0.1; SOFS: rho=–0.08, P=0.49), and PANSS baseline scores (PANSS: rho=0.01, P=0.92; SOFS: rho=–0.03, P=0.77). With respect to the age at onset, PANSS scores did not have a significant correlation (rho=–0.05; P=0.64) while SOFS scores did have (rho=–0.27; P=0.02).

SOFS total score was 14 (indicating no impairment) in 27 (29%), 15-28 (indicating mild-moderate impairment) in 39 (41.9%), and 29 or more (indicating moderate-extreme impairment) in 27 (29%). We divided the patients into three equal groups with increasing order of DUP. Table 2 shows the number of patients with different degrees of impairment across these three groups. There was a significant association between the DUP categories and functional impairment (Kendall's Tau-b=0.194; P=0.025), indicating that those with the longest DUP had the highest functional impairment. This was also true of those who were adherent for at least 80% of the follow-up period (Kendall's Tau-b=0.229; P=0.01).

Table 2.

Comparison between different DUP categories and degrees of impairment (at the follow-up interval)

DISCUSSION

The most important finding of this study is that longer duration of untreated psychosis is associated with poorer symptomatic and functional outcome at 1-year follow-up in a sample of treatment-naοve schizophrenia patients in south India.

The study has several methodological strengths: the diagnosis of schizophrenia was established using a structured interview schedule (CDIS-IV) by a trained psychiatrist; DUP was measured using a standardized scale (IRAOS); both symptomatic and functional outcomes were assessed using standardized scales by raters blind to the information about DUP; and the follow-up rate was high (78.2% of the initial cohort and 80.2% of the surviving patients). Thus, the study meets all the methodological criteria suggested by Marshall and colleagues[2] in researching DUP and outcome in schizophrenia. This provides a firm evidence for the DUP in being a predictor of the outcome of schizophrenia in a LAMI country like India.

The mean DUP in our sample (90.2 weeks) was comparable to that reported in earlier studies in India (98.8 weeks,[16] 85.8 weeks,[17] 97.2 weeks[18]). It may be noted that mean DUP in India is lower than that in many other low-income countries[6] like Argentina (468 weeks), Nigeria (152 weeks), and Pakistan (110 weeks). However, it is considerably higher than that in high-income countries with arguably better healthcare delivery systems. This calls for urgent and comprehensive approaches to reduce DUP in LAMI countries.

The association between DUP and functional impairment was fairly modest in our study. Studies have shown that the beneficial effect of reducing DUP is also fairly modest.[19] However, when seen in the background of the fact that schizophrenia is one of the leading causes of disability despite advances in its treatment and that DUP is one of the few modifiable prognostic indicators of outcome, no effort to reduce DUP should be spared in ensuring a better outcome.

One reason for a modest correlation between DUP and outcome in our sample could be the “flooring effect:” the level of functional impairment was very low in a majority of patients at 1-year follow-up. Though no specific and structured psychosocial services were provided, nearly three-fourths of the patients had either no or mild functional impairment, in the entire sample. All patients lived with their family members, most of whom took keen interest in patients’ recovery. Additionally, lack of co-morbid substance use disorder, which is associated with poor outcome of schizophrenia even in the short term,[20,21] could have contributed to a satisfactory outcome in these patients. Such a situation, where there is little variability in the outcome measures, does not yield itself to the exploration of robust associations between predictor and outcome variables.

There was a positive correlation between DUP and severity of the illness in the baseline. However, at 1-year follow-up, neither psychopathology score nor social functioning score was correlated with baseline psychopathology score. It is unlikely that the association between DUP and outcome was confounded by baseline severity. One cannot, however, rule out the possible role for other confounding factors, which could have led some patients to have longer DUP as well as poorer outcome. For instance, all patients were living with their families. It is conceivable that the quality of family members’ relationship and attitude toward the ill persons could have influenced the time taken in seeking help as well as the outcome. This may be tested in further studies.

We had an attrition of about 20% in our sample. Patients’ experience of substantial reduction in their symptoms was the most common cause for this. This is consistent with the previous literature on failure to follow-up among schizophrenia patients in India.[22] These patients were not significantly different from those who were followed up, except the fact that there was female preponderance in those who could not be followed up. The association of DUP with outcome is not known to be different between the sexes. Hence, non-inclusion of these patients could not have substantially influenced the results. However, we cannot rule out the possibility that women who dropped out could have been non-adherent to treatment and could have had poor outcome. Generalizability of the study findings may be limited by this factor. Another limitation of the study is that the sample size was not calculated formally. Rather, all consecutive patients meeting the study criteria within the recruitment period were included.

In summary, this study examined the association of DUP and outcome of patients with never-treated schizophrenia and found that longer DUP is associated with poorer outcomes in the context of a LAMI country. Measures to reduce the inordinate delay experienced by some patients in reaching treatment centers may improve their outcome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge the contribution of the raters, Drs. R Shankar and B M Veena and social workers, Prabhanna and Mounesh.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Perkins DO, Gu H, Boteva K, Lieberman JA. Relationship between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in first-episode schizophrenia: A critical review and meta-analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1785–804. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.10.1785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marshall M, Lewis S, Lockwood A, Drake R, Jones P, Croudace T. Association between duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in cohorts of first-episode patients: A systematic review. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:975–83. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.9.975. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hopper K, Wanderling J. Revisiting the developed versus developing country distinction in course and outcome in schizophrenia: Results from ISoS, the WHO collaborative follow up project: International Study of Schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2000;26:835–46. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Harrison G, Hopper K, Craig T, Laska T, Siegel C, Wanderling J, et al. Recovery from psychotic illness: A 15- and 25-year international follow-up study. Br J Psychiatry. 2001;178:506–17. doi: 10.1192/bjp.178.6.506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Alem A, Kebede D, Fekadu A, Shibre T, Fekadu D, Beyero T, et al. Clinical course and outcome of schizophrenia in a predominantly treatment-naïve cohort in rural Ethiopia. Schizophr Bull. 2009;35:646–54. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbn029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Large M, Farooq S, Nielssen O, Slade T. Relationship between gross domestic product and duration of untreated psychosis in low- and middle-income countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2008;193:272–8. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.041863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Farooq S, Large M, Nielssen O, Waheed W. The relationship between the duration of untreated psychosis and outcome in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Schizophr Res. 2009;109:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2009.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Philip M, Gangadhar BN, Jagadisha, Velayudhan L, Subbakrishna DK. Influence of duration of untreated psychosis on the short-term outcome of drug-free schizophrenia patients. Indian J Psyhciatry. 2003;45:158–60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tirupati NS, Rangaswamy T, Raman P. Duration of untreated psychosis and treatment outcome in schizophrenia patients untreated for many years. Aust NZJ Psychiatry. 2004;38:339–43. doi: 10.1080/j.1440-1614.2004.01361.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Robins LN, Cottler LB, Bucholz KK, Comptom WM, North CS, Rourke KM. Diagnositc interview schedule for the DSM-IV (DIS-IV) 2000 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hafner H, Riecher-Rossler A, Hambrecht M. IRAOS: An instrument for the assessment of onset and early course of schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 1992;6:209–23. doi: 10.1016/0920-9964(92)90004-o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Venkatesh BK, Thirthalli J, Naveen MN, Kishore Kumar KV, Arunachala U, Venkatasubramanian G, et al. Sex difference in age of onset of schizophrenia: Findings from a community-based study in India. World Psychiatry. 2008;7:173–6. doi: 10.1002/j.2051-5545.2008.tb00191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA. The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 1987;13:261–76. doi: 10.1093/schbul/13.2.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saraswat N, Rao K, Subbakrishna DK, Gangadhar BN. The social occupational functioning scale (SOFS): A brief measure of functional status in persons with schizophrenia. Schizophr Res. 2006;81:301–9. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.09.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Norman RM, Malla AK. Duration of untreated psychosis: A critical examination of the concept and its importance. Psychol Med. 2001;31:381–400. doi: 10.1017/s0033291701003488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gangadhar BN, Panner SC, Subbakrishna DK, Janakiramaiah N. Age-at-onset and schizophrenia: Reversed gender effect. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2002;105:317–19. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2002.1153.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murthy GV, Janakiramaiah N, Gangadhar BN, Subbakrishna DK. Sex difference in age at onset of schizophrenia: Discrepant findings from India. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1998;97:321–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1998.tb10010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thirthalli J, Phillip M, Gangadhar BN. Influence of duration of untreated psychosis on treatment response in schizophrenia: A report from India. Schizphr Bull. 2005;31:183. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Larsen TK, Friis S, Haahr U, Joa I, Johannessen JO, Melle I, et al. Early detection and intervention in first-episode schizophrenia: A critical review. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2001;103:323–34. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2001.00131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Green AI, Tohen MF, Hamer RM, Strakowski SM, Lieberman JA, Glick I, et al. First episode schizophrenia-related psychosis and substance use disorders: Acute response to olanzapine and haloperidol. Schizophr Res. 2004;66:125–35. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sorbara F, Liraud F, Assens F, Abalan F, Verdoux H. Substance use and the course of early psychosis: A 2-year follow-up of first-admitted subjects. Eur Psychiatry. 2003;18:133–6. doi: 10.1016/s0924-9338(03)00027-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thara R, Rajkumar S. A study of sample attrition in follows up of schizophrenia. Indian J Psychiatry. 1990;32:217–2. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]