Abstract

Objectives:

To assess the myths, beliefs and perceptions about mental disorders and health-seeking behavior in general population and medical professionals of India.

Materials and Methods:

A cross-sectional study was carried out with a sample of 436 subjects (360 subjects from urban and rural communities of Delhi and 76 medical professionals working in different organizations in Delhi). A pre-tested questionnaire consisting items on perceptions, myths, and beliefs about causes, treatment, and health-seeking behavior for mental disorders was used. The collected data were statistically analyzed using computer software package Epi-info. Appropriate tests of significance were applied to detect any significant association.

Results:

The mental disorders were thought to be because of loss of semen or vaginal secretion (33.9% rural, 8.6% urban, 1.3% professionals), less sexual desire (23.7% rural, 18% urban), excessive masturbation (15.3% rural, 9.8% urban), God's punishment for their past sins (39.6% rural, 20.7% urban, 5.2% professionals), and polluted air (51.5% rural, 11.5% urban, 5.2% professionals). More people (37.7%) living in joint families than in nuclear families (26.5%) believed that sadness and unhappiness cause mental disorders. 34.8% of the rural subjects and 18% of the urban subjects believed that children do not get mental disorders, which means they have conception of adult-oriented mental disorders. 40.2% in rural areas, 33.3% in urban areas, and 7.9% professionals believed that mental illnesses are untreatable. Many believed that psychiatrists are eccentric (46.1% rural, 8.4% urban, 7.9% professionals), tend to know nothing, and do nothing (21.5% rural, 13.7% urban, 3.9% professionals), while 74.4% of rural subjects, 37.1% of urban subjects, and 17.6% professionals did not know that psychiatry is a branch of medicine. More people in rural areas than in urban area thought that keeping fasting or a faith healer can cure them from mental illnesses, whereas 11.8% of medical professionals believed the same. Most of the people reported that they liked to go to someone close who could listen to their problems, when they were sad and anxious. Only 15.6% of urban and 34.4% of the rural population reported that they would like to go to a psychiatrist when they or their family members are suffering from mental illness.

Conclusion:

It can be concluded from this study that the myths and misconceptions are significantly more prevalent in rural areas than in urban areas and among medical professionals, and the people need to be communicated to change their behavior and develop a positive attitude toward mental disorders so that health-seeking behavior can improve.

Keywords: Mental illness, misconceptions, stigma, faith-healer, health-seeking behavior

INTRODUCTION

Mental and behavioral disorders are present at any point in time in about 10% of the adult population worldwide. The burden of mental disorders is maximal in young adults, the most productive section of the population. Neuropsychiatry conditions together account for 10.96% of the global burden of disease as measured by disability-adjusted life years (DALYs). Projections estimate that by the year 2020, neuropsychiatric conditions will account for 15% of disabilities worldwide, with unipolar depression alone accounting for 5.7% of DALYs and will stand second in top 10 leading causes of disability.[1] The total economic costs of mental disorders are substantial in terms of gross national product (GNP) loss. In most countries, families bear a significant proportion of these economic costs because of the absence of public funded comprehensive mental health service networks. Families also incur social costs, such as the emotional burden of looking after disabled family members, diminished quality of life for carers, social exclusion, stigmatization, and loss of future opportunities for self-improvement.[2] This burden emphasizes the need of scientific studies in various aspects of mental disorders.

In India, the prevalence of mental disorders ranges from 10 to 370 per 1000 population in different parts of the country.[3,4] The median conservative estimate of 65 per 1000 population has been given by Gururaj et al.[5] The rates are higher in females by approximately 20-25%. As far as causation of mental morbidity is concerned, there are many factors similar to any other world community, but delayed health-seeking behavior, illiteracy, cultural and geographic distribution of people are special for India.

Access to adequate mental health care always falls short of both implicit and explicit needs. This can be explained in part by the fact that mental illness is still not well understood, often ignored, and considered a taboo. The mentally ill, their families and relatives, as well as professionals providing specialized care, are still the object of marked stigmatization. These attitudes are deeply rooted in society. The concept of mental illness is often associated with fear of potential threat of patients with such illnesses. Fear, adverse attitude, and ignorance of mental illness can result in an insufficient focus on a patient's physical health needs. The belief that mental illness is incurable or self-inflicted can also be damaging, leading to patients not being referred for appropriate mental health care.[6] It is found that current treatment coverage ranges from 15 to 45% only and there is, therefore, gross underutilization of services.[7–9] Many factors contribute to such underutilization of services. The attitude of individual patient toward his or her mental disorders is important as far as health seeking is concerned. Adverse attitude toward psychiatry and psychiatrists has been observed among medical professionals,[10] which could be another hindrance in providing adequate mental health services. It is pertinent to study the perceptions, myths, beliefs, and health-seeking behavior for mental health of population.

“Myth” usually refers to a story of forgotten or vague origin, basically religious or supernatural in nature, which seeks to explain or rationalize one or more aspects of the world or a society. The study of myth must not and cannot be separated from the study of religion, religious beliefs, or religious rituals.[11] Belief is usually defined as a conviction of the truth of a proposition without its verification; therefore, a belief is a subjective mental interpretation derived from perception, contemplation (reasoning), or communication. Belief is always associated with a denial of reality. The renunciation of belief is then an educational task and a psychological struggle, both liable to encounter much resistance. Psychoanalytic treatment cannot itself dispense with belief, for the transference, which reactivates infantile processes, demands that the patient lend credence to the analyst's words even though these do not belong to the realm of demonstrable truth. Therefore, in most of the cases, psychoanalysis is temporarily replacing one belief by another.[12] Some proposed an idea that many (if not most) faith-based religious beliefs are actually delusional beliefs.[13,14] Myths and beliefs are also responsible for practices which could be harmful to health. The objective of scientific study on myths and belief should be to identify and replace them with truth to ensure better health based on scientific knowledge.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

A comparative cross-sectional study was designed, which is the part of ongoing multiple studies, with the objective to assess belief, myths, perception, and health-seeking behavior of the population. The sample size was calculated on the basis of expected frequency of myths and health-seeking behavior for mental disorders in population, which was taken as 50%. Taking a worst acceptable frequency of 45% with 95% confidence, it came out to be 384.[15] To get this sample, three groups were selected conveniently consisting of the following: a) a sample of 180 adult subjects (more than 15 years of age) randomly selected during house-to-house visit from a rural community having a population of approximately 5000; b) 180 adults from an urban community consisting of a population of approximately 5500; and c) 76 medical professionals from different health organizations of Delhi.[16] The purpose of inclusion of data on medical professionals was to make comparison with the general population. It is to elucidate whether their medical scientific knowledge has any bearing on belief system related to mental health. Data on myths, religion, cultural belief system, and causes and treatment of mental disorders were collected using a pre-tested questionnaire. The questionnaire consists of various components: A. socio-demographic characteristics (10 items); B. attitude, belief, myths, and perception about mental diseases (11 items); C. causes of mental disorders (1 item having multiple responses); D. treatment of mental disorders (1 item having multiple responses); E. opinion about psychiatry and psychiatrists (2 items); F. religion and belief system of people (21 items): only 5 were analyzed; and G. health-seeking behavior (4 items): 3 were directly related to mental disorder and were analyzed. Components B-E were adopted from a validated questionnaire.[10,16] Scoring for questions on attitude, belief, and perception was taken on 3-point or 5-point Likert scale and analysis of such questions was carried out using only affirmative responses. Terms such as neurotransmitter, Intelligence Quotient (IQ), eccentric, etc. were explained in the questionnaire itself to reduce the interviewer bias. Data from the general population were obtained using the structured questionnaire by two trained doctors to decrease the reporting bias. In a pilot testing, inter-observer reliability was good as kappa was 65%. Unacceptability bias was minimized by standardizing the questionnaire. Test-retest reliability of questionnaire was 52% when the same questionnaire was applied after a 2-week interval. The questionnaire was translated from English to Hindi with the help of Hindi experts and then re-translated into English by another expert of public health who was not aware of the English version. It was checked with the original English version and any discrepancy was removed with discussion. Again, it was translated by a bilingual expert into Hindi version to suit the language understanding of the study subjects.

Data were analyzed with the help of Epi-info software package of world health organization (WHO). Tests of significance such as chi-square test for qualitative data were used for comparison within three groups. The purpose of the study was explained to all subjects and voluntary verbal informed consent was obtained from them before filling up of questionnaire. The responses were kept anonymous to encourage candid opinions. Each adult subject in the family in community survey and hospital in medical professional groups was interviewed while keeping maximum possible privacy.

RESULTS

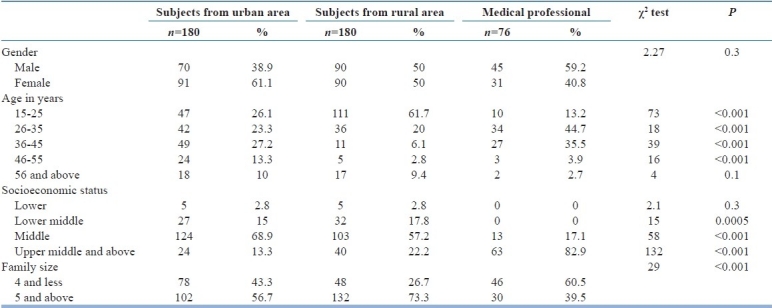

The sample from urban and rural areas and medical professionals were significantly different when their age groups, socioeconomic status, and family size were compared [Table 1]. However, gender-wise distribution of study subjects in different samples was not significantly different. Rural sample was much younger in age, belonged to middle class and bigger family size as compared to urban and medical professionals.

Table 1.

Socioeconomic characteristics of the study population

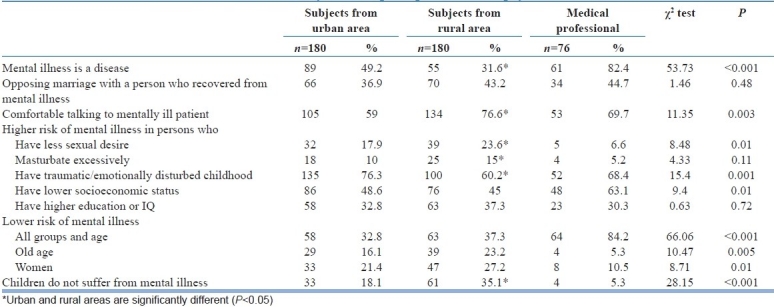

Half of the urban subjects had considered mental illness as a disease, as compared to just 31.6% people from rural area. Despite this, 76.6% of rural respondents claimed that they would feel comfortable talking to a person with mental disorder, but only 59% of urban respondents agreed to this. More medical professionals (69.7%) agreed to be comfortable.

As far as risk of mental disorders is concerned, 23.6% believed that having less sexual desire makes a person prone to mental illness, but only 17.9% of urban subjects agreed to it and even lesser (6.6%) proportion of professionals believed so. One-third of the subjects believed that higher education and high IQs could be the cause of mental disorders [Table 2].

Table 2.

Attitude, beliefs, myths, and perception toward psychiatric disorders

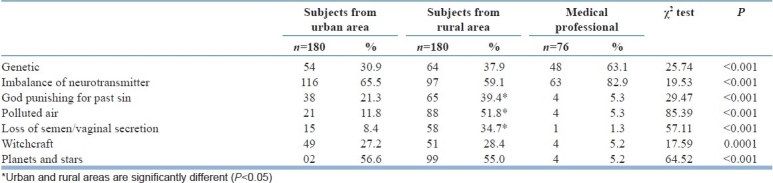

A significantly higher proportion of rural subjects (34.7%) believed that loss of semen/vaginal secretion is a cause of mental disorder, as compared to 8.4% of urban subjects and 1.3% of professionals (χ2 =57.1, df=2, P<0.001). Similarly, 52% of rural population believed that polluted air causes mental illness, as compared to 11.8% urban subjects and 5.3% professionals who thought so (χ2 =85.3, df=2, P<0.001). Similarly, significantly higher proportion (39.4%) of rural respondents believed that mental illness is the punishment given to patients by God for their past sin, as compared to urban subjects and professionals (χ2 =29.4, df=2, P<0.001). Biological reasons such as genetic and imbalanced neurotransmitters were also mentioned by the respondents to be the cause of mental disorders [Table 3].

Table 3.

Causes of psychiatric disorders

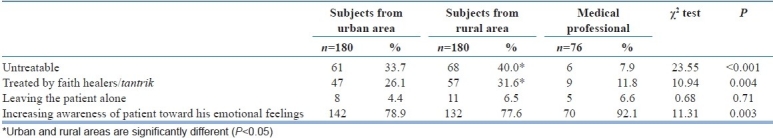

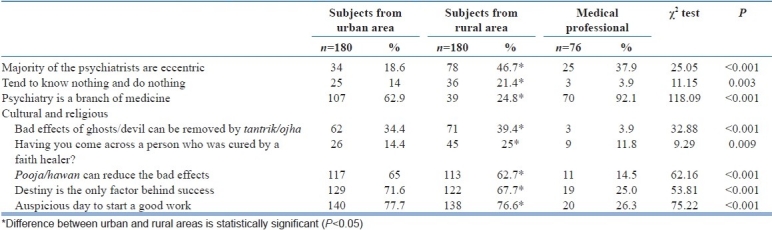

The results of their attitudes toward treatment of mental disorders highlighted the ignorance prevailing in Indian society and urgent need of awareness among people. 33.7% subjects in rural areas and 40% in urban areas and 8% of the professionals believed that mental illnesses are untreatable. This difference was statistically significant (χ2 =23.5, df=2, P<0.001). 26.1% in rural areas, 31.6% in urban areas, and 11.8% of the professionals believed that the disease can be treated by faith healers or tantriks (χ2 =10.9, df=2, P=0.004) [Table 4]. This could be due to having an adverse attitude toward psychiatrists because 18.6% of the urban population believed psychiatrists to be eccentric, as compared to about 47% of the rural population. Very high proportion of professionals also believed the same (37.9%).

Table 4.

Attitude toward treatment of psychiatric disorders

Regarding cultural and religious beliefs, significant differences were seen between the three communities [Table 5]. A large number of people in all three groups believed that daily worshipping and keeping fasts can reduce the bad effects. A significant proportion of people believed that destiny or work started on an auspicious day can be the only factors behind one's successes. 39.4% people in rural areas, 34.4% in urban areas, and 4% of the professionals believed in bad effects of ghosts/devil/witches. 25% of the rural respondents even claimed to have come across a person getting cured this way, but only 14% of the urban respondents believed so.

Table 5.

Opinion about psychiatry and psychiatrists and beliefs system

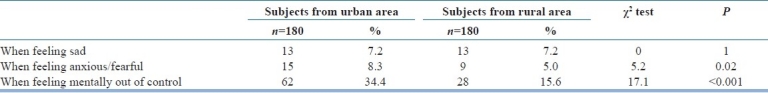

Health-seeking behavior was assessed in urban and rural sample only. The health-seeking behavior of people yielded highly unfavorable results as less than 13.6% of people said that they would prefer going to a psychiatrist when they feel sad or anxious and 25% would prefer the same when they feel out of control. These proportions of mental health seeking except for feeling sad were significantly more in urban population than in rural population (for anxiety: χ2 =5.2, df=1, P<0.02; for out of control situation: χ2 =17.1, df=1, P<0.001) [Table 6].

Table 6.

Reasons given by subjects for visiting a psychiatrist

DISCUSSION

In the present study, 36.9% of rural subjects, 43.2% of urban subjects, and 44.7% of the medical professionals reported that they would oppose marriage with a person recovered from mental illness. One-third of the subjects stated that they would not be comfortable talking to a recovered person. This indicates that in addition to the obvious suffering caused by mental disorders, there is a hidden burden of stigma and discrimination. In both low-income and high-income countries, the stigmatization of people with mental disorders has persisted throughout history. Stigma is manifested as bias, stereotyping, fear, embarrassment, anger, rejection, or avoidance. For people suffering from mental disorders, there have been violations of basic human rights and freedoms, as well as denials of civil, political, economic, and social rights, in both institutions and communities. Physical, sexual, and psychological abuses are everyday experiences for many people with mental disorders. They face rejection, unfair denial of employment opportunities, and discrimination in access to services, health insurance, and housing. Much of this goes unreported, and therefore the burden remains unquantified.[17]

Generally, people do not sympathize with a mentally ill person because they impart value to the patient and believe that the person lacks the will power to pull himself or herself up and is just not making an effort.[18] Many times patients are ignored, isolated, or taken to sorcerers and faith healers, and treated with rituals rather than with appropriate medications. It is also recognized that labeling such people, and then drugging them, is destructive and morally wrong.[18] Problem is lying in the society that lacks knowledge of coping methods. Gadit and Reed[19] reported that only 5% people in Pakistan came to the attention of a psychiatrist. This difference could be due to the cultural and religious differences existing and lack of availability of adequate number of psychiatrists in Pakistan. It was found that faith healers are important health care providers, especially with regard to treatment in less-privileged and less-resourceful people. This finding correlates with the finding of a study conducted by Jiloha and Kishore.[20] The present study also revealed that many people have belief in supernatural powers as the causative agents of mental illness, which has remained the same more than three decades after Neiki[21] had reported. In our study, the majority of patients who believed in supernatural agents as the causative factors of their illness were from rural areas having low socioeconomic status. These findings are similar to the documented findings of Sethi et al. and Trivedi and Sethi.[22–24]

When it comes to urban India, even university graduates and some patients who did not finally believe in supernatural causes of mental illness had consulted faith healers. A similar practice was observed by Kua et al. and Rizali et al.[25,26]

There are various other myths regarding the causes of mental illness. Bad parenting, air pollution, loss of semen, poor diet, past sin, curse of God, and evil eye are some of the important myths related to its causation. People usually do not accept the medical reasons for mental disorders. That is why, they always criticize medical treatment modalities, particularly, electroconvulsive therapy. Many people believed that children and adolescents do not develop severe illness as frequently as adults.

The present study indicates that large numbers of subjects have belief that prayer or pooja or hawan can reduce the bad effects and that ghost can be removed by tantriks/ojha. Such belief systems in all sections of the society prevent the patients from coming forward to seek psychiatric help when they suffer from abnormal behaviors. Another reason of not seeking help is having the adverse attitude toward psychiatry and psychiatrists. In the present study, a large proportion of subjects, particularly from rural area, believed that psychiatrists are eccentric and do nothing.

There are some positive outcomes as well from our study, such as that more people now recognized mental illness as a disease (49.2% urban, 31.6% rural, and 82.4% professionals). More people were comfortable talking to a patient who recovered from mental illness, among rural (76.6%) than urban subjects (59%) and medical professionals (69.7%). This could be due to the acceptance of mentally ill person in the rural society.

Myths and misconceptions about mental illness contribute to the stigma, which leads many people to be ashamed and prevents them from seeking help. Stigma is something about a person that causes her or him to have a deeply compromised social standing, a mark of shame or discredit. Generally, people who have mental disorders are considered lazy, unintelligent, worthless, stupid, unsafe to be with, violent, always in need of supervision, possessed by demons, recipients of divine punishment, unpredictable, unreliable, irresponsible, without conscious, incompetent to marry and raise children, unable to work, affects rich people, increasingly unwell throughout life, and in need of hospitalization.[17] Unfortunately, such misconceptions remain predominant in people who are supposed to deliver the health care services. It is found that medical professionals share high proportion of misconceptions and have discriminatory attitude toward psychiatry and patients of mental disorders.[10,16] This should not happen because effective treatment exists for almost all mental illnesses. Worse, the stigma experienced by people with a mental illness can be more destructive than the illness itself. Widespread social stigma, myths, and adverse belief systems of mental illness cannot be removed by just increasing the public awareness, but rather requires a comprehensive community-based program based on psychosocial understanding of the disease.

Footnotes

Source of Support: Nil

Conflict of Interest: None declared

REFERENCES

- 1.Mathers CD, Lopez AD, Murray CJL. The burden of disease and mortality by condition: Data, methods, and results for 2001. In: Lopez AD, Mathers CD, Ezzati M, Jamison DT, Murray CJ, editors. Global burden of disease and risk factors. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Investing in mental health. Magnitude and burden of mental disorders. Geneva: WHO; 2003. WHO; p. 8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Reddy MV, Chandrashekhar CR. Prevalence of mental and behavioural disorders in India: A meta-analysis. Indian J Psychiatry. 1998;40:149–57. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murali MS. Epidemiological study of prevalence of mental disorders in India. Indian J Commun Med. 2001;9:34–8. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gururaj G, Girish N, Issac MK. Mental, neurological and substance abuse disorders: Strategies towards a systems approach. In. Burden of disease in India. National Commission on Macroeconomics and Health. Government of India. 2005 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kishore J. Schizophrenia: Myths and reality. Rationalist Voice. 2004:23–6. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferris TG. An epidemic of discontinuity in health care. Ambulat Pediatr. 2004;4:197–8. doi: 10.1367/1539-4409(2004)4<197:TEODIH>2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chisholm D, Lund C, Saxena S. Cost of scaling up mental healthcare in low- and middle-income countries. Br J Psychiatry. 2007;191:528–35. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.107.038463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gater R, de Almeida e Sousa B, Barrientos G, Caraveo J, Chandrashekar CR, Dhadphale M, et al. The pathways to psychiatric care: A cross-cultural study. Psychol Med. 1991;21:761–74. doi: 10.1017/s003329170002239x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mukherjee R, Kishore J, Jiloha RC. Attitude towards psychiatry and psychiatric illness among medical professionals. Delhi Psychiatry Bull. 2006;9:34–8. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bascom W. The forms of folklore: Prose narratives. In: Alan Dundes., editor. Sacred Narrative: Readings in the Theory of Myth. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1984. pp. 5–29. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Freud S, Breuer J. Studies on hysteria. Standard Edi. 1895:2. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dawkins R. Has the world changed? The Guardian. 2001-10-11 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harris S. The end of faith: Religion, terror, and the future of reason. W.W. Norton and Company. 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sample size determination in health studies: A practical Manual. Geneva: WHO; 1991. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kishore J, Mukherjee R, Parashar M, Jiloha RC, Ingle GK. Beliefs and Attitudes towards mental health among medical professionals in Delhi. Indian J Commun Med. 2007;32:198–200. [Google Scholar]

- 17.The Mental Health Context (Mental Health Policy and Service Guidance Package) Geneva: WHO; 2003. WHO. [Google Scholar]

- 18.WHO. Mental health and substance abuse, including Alcohol in the South-East Asia Region of WHO. WHO Regional Office of South-East Asia New Delhi. 2001 Jul 1; [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gadit A, Reed V. Culture and mental health-Pakistan's perspective. 1st ed. Karachi: Hamdard Foundation; 2004. pp. 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiloha RC, Kishore J. Supernatural beliefs, mental illness and treatment outcome in Indian Patients. Indian J Soc Psychiatry. 1997;13:106–13. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Neki JS. Psychiatry in South East Asia. Br J Psychiatry. 1973;123:257. doi: 10.1192/bjp.123.3.257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sethi BB, Sachdeva S, Nag D. Socio-cultural factors in practice of psychiatry in India. Am J Psychother. 1965;3:445–54. doi: 10.1176/appi.psychotherapy.1965.19.3.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sethi BB, Trivedi JK, Sitholey P. Traditional healing practices in psychiatry. Indian J Psychiatry. 1977;19:9–13. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Trivedi JK, Sethi BB. A psychiatric study of traditional healers in Lucknow city. Indian J Psychiatry. 1979;21:133–7. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kua EH, Chew PH, Ko SM. Spirit possession and healing among Chinese psychiatric patients. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;88:447–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1993.tb03489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rizali SM, Khan U, Hasanah CI. Belief in supernatural causes of mental illness male patients: Impact on treatment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1996;94:229–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1996.tb09854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]