Abstract

Objective: International differences in disease prevalence rates are often reported and thought to reflect different lifestyles, genetics, or cultural differences in care-seeking behavior. However, they may also be produced by differences among health care systems. We sought to investigate variation in the diagnosis and management of a “patient” with exactly the same symptoms indicative of depression in 3 different health care systems (Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States).

Method: A factorial experiment was conducted between 2001 and 2006 in which 384 randomly selected primary care physicians viewed a video vignette of a patient presenting with symptoms suggestive of depression. Under the supervision of experienced clinicians, professional actors were trained to realistically portray patients who presented with 7 symptoms of depression: sleep disturbance, decreased interest, guilt, diminished energy, impaired concentration, poor appetite, and psychomotor agitation or retardation.

Results: Most physicians listed depression as one of their diagnoses (89.6%), but German physicians were more likely to diagnose depression in women, while British and American physicians were more likely to diagnose depression in men (P = .0251). American physicians were almost twice as likely to prescribe an antidepressant as British physicians (P = .0241). German physicians were significantly more likely to refer the patient to a mental health professional than British or American physicians (P < .0001). German physicians wanted to see the patient in follow-up sooner than British or American physicians (P < .0001).

Conclusions: Primary care physicians in different countries diagnose the exact same symptoms of depression differently depending on the patient's gender. There are also significant differences between countries in the management of a patient with symptoms suggestive of depression. International differences in prevalence rates for depression, and perhaps other diseases, may in part result from differences among health care systems in different countries.

International differences in the diagnosis and management of diseases are of increasing interest to epidemiologists and health services researchers. Reported country differences in disease prevalence rates are assumed to be real, and the ensuing search for underlying reasons has focused on family history and genetics and on cultural differences in lifestyles and risk behaviors. However, it is equally possible that the same signs and symptoms of disease are diagnosed and managed differently in various countries (or health care systems), hence the international differences in disease prevalence rates (Table 1).1–4 Variability in provider behavior is increasingly invoked as an explanation for within-country health disparities; however, this explanation is seldom extended to an understanding of international health and medical care variations.5,6 Furthermore, as health care reform is debated in the United States, there is interest in lessons to be learned from the way other countries organize and finance their health care systems and how this affects health outcomes and the costs of care.7–9 International comparative health services and policy research remains limited by reliance on existing medical records with their well-known deficiencies: they are collected for various administrative and billing purposes, they may not reflect what actually occurs during any clinical encounter (eg, legal and financial pressures to “code up”), and subtle processes of medical care are seldom captured in the medical record (eg, the number and types of questions asked). Sophisticated statistical analyses of such data can never produce unconfounded estimates of relative contributors to health care variations. Moreover, differences among patients and in the severity of symptoms presented for diagnosis and management always bedevil the explanation of health care variations.

Table 1.

Mental Health Disorders and Resources by Countrya

| Variable | Germany | United Kingdom | United States |

| Age-standardized disability-adjusted life years per 100,000 (in 2004) | |||

| Unipolar depressive disorders | 955 | 961 | 1,455 |

| Bipolar disorder | 184 | 184 | 184 |

| Prevalence (12 mo) World Mental Health Composite International Diagnostic Interview/DSM-IV disorders, (%) | 9.1 | NA | 26.3 |

| Lifetime risk at age 75 y of DSM-IV disorders, (%) | 33.0 | NA | 55.3 |

| Mental health resources, mean number | |||

| Total psychiatric beds per 10,000 population | 7.5 | 5.8 | 7.7 |

| Psychiatrists per 100,000 population | 11.8 | 11.0 | 13.7 |

| Psychiatric nurses per 100,000 population | 52.0 | 104.0 | 6.5 |

| Neurologists per 100,000 population | 3.4 | 1.0 | 4.5 |

| Psychologists per 100,000 population | 51.5 | 9.0 | 31.1 |

| Social workers per 100,000 population | 477 | 58 | 35 |

In contrast to earlier observational research, we conducted an experiment to simultaneously estimate the unconfounded effect of patient attributes (gender, age, race, and socioeconomic status), physician characteristics (gender and years of clinical experience), and country setting (health care system) on the diagnosis and management of a “patient” presenting with signs and symptoms suggestive of depression. Our factorial experiment sought to address the following questions:

Do primary care doctors in Germany, the United Kingdom, and the United States diagnose patients differently when exactly the same symptoms suggestive of depression are present?

Is the clinical management of depression different between the 3 countries, and, if so, what may explain any such differences?

Clinical Points

♦International differences in disease prevalence rates are often reported and are thought to reflect variations in lifestyles, genetics, or culture.

♦American physicians were more likely than British or German physicians to diagnose depression in men and almost twice as likely as British physicians to prescribe an antidepressant.

♦Primary care physicians in different countries diagnose depression differently depending on the patient's gender even when the same symptoms are present.

METHOD

Our factorial experiment was conducted between 2001 and 2006 in 3 countries with very different health care systems: Germany with decentralized care administered by social security agencies; the United Kingdom with its government-supported, tax-based National Health Service; and the United States with a largely employment-based private insurance system. Randomly sampled primary care doctors from each of these 3 countries viewed a clinically authentic videotape of a patient presenting signs and symptoms strongly indicative of depression.

Under the supervision of experienced clinicians, professional actors were trained to realistically portray a patient who presents with the signs and symptoms of depression. Vignette content was developed with input from experienced clinicians. Patients presented with 7 symptoms of depression (sleep disturbance, decreased interest, guilt, diminished energy, impaired concentration, poor appetite, and psychomotor agitation or retardation); suicidal ideation was omitted as being too indicative of depression (Table 2).10 Video presentations permit the inclusion of often subtle nonverbal clues (eg, a dejected affect and anxiety). Since patients seldom present as textbook cases, several other symptoms (eg, diffuse pain, dyspnea) were also included to increase the authenticity of the case.

Table 2.

Signs/Symptoms of Depression (SIGECAPS) Embedded (and excluded) and Distractions in the Clinical Vignette Presentation

| Classic symptoms of depression that were included |

| Sleep Disturbance |

| Decreased Interest |

| Guilt |

| Reduced Energy |

| Inability to Concentrate |

| Poor Appetite |

| Psychomotor Retardation |

| Symptoms of depression that were not included |

| Suicidal Ideation |

| Nonverbal clues |

| Dejected affect |

| Anxiety |

| Distractions added to vignette |

| Diffuse pain |

| Recently stopped smoking |

| Shortness of breath had sent patient to emergency room recently |

| Headaches |

Patients depicted in the vignette spoke directly to the camera and to an unseen physician. The vignettes varied 5 factors: (1) patient age (55 or 75 years); (2) patient gender; (3) patient socioeconomic status (depicted by their current or former occupation as a janitor or school teacher); (4) patient race (black or white) in the United Kingdom and United States, but not in Germany because black patients are infrequently encountered; and (5) unseen physician gender. In the United Kingdom and United States, the design was a half replicate of a 25 factorial with 16 vignettes. In Germany, the design was a full replicate of a 24 factorial, also 16 vignettes. For the vignettes viewed in the United Kingdom, patients and the unseen physician had British accents and vocabulary, while an American accent and vocabulary was portrayed by the same actors in the vignettes viewed in the United States. The vignettes were dubbed into German for those viewed in Germany. The physicians were asked open-ended questions such as, would you refer the patient, would you prescribe any medication, or would you recommend any lifestyle change? Additional details concerning this experimental approach and the use of clinical vignettes are presented elsewhere.5,6

The physician subjects were randomly selected from country-specific lists of physicians. The physicians were told that the study was investigating clinical decision making. One of the 2 video vignettes presented a patient with symptoms suggestive of depression and the other presented a patient with symptoms suggestive of coronary heart disease (not included here). In Germany, generalist or family physicians practicing in the North Rhine-Westphalia region were sampled. In the United Kingdom, general practitioners were sampled from health authority lists in the Midlands or Surrey (half of the interviews were in each area). In the United States, internists and family practitioners were sampled from physicians practicing in Massachusetts. The physicians were recruited into 4 strata representing gender by 2 levels of clinical experience. Experience was defined by the year of graduation from medical school in the United Kingdom and United States and the year of licensure in Germany. Less experienced physicians were recognized as having graduated from medical school (in the United Kingdom or United States) between 1989 and 1996 (or were licensed in Germany between 1998 and 2004) and more experienced physicians as having graduated from medical school (in the United Kingdom or United States) between 1965 and 1979 (or were licensed in Germany between 1974 and 1988).

Given our interest in comparing physician behavior in the 3 countries, subjects were eligible only if they had completed their medical training in the country in which they practiced. The balanced design required 128 physician subjects from each country: 32 of each gender by experience strata with 2 physicians to view each of the 16 vignettes. There were a total of 384 physicians. Phone calls were made to randomly selected physicians to screen for eligibility. Interviews took place in the physician's office generally between appointments with real patients. Physicians received a modest financial acknowledgment for their participation (€100 in Germany, ₤50 in the United Kingdom, and $100 in the United States). All physicians signed informed consent prior to their participation. The study was approved by New England Research Institutes’ Institutional Review Board and the ethics committees in Germany and the United Kingdom.

To preserve the orthogonal (independent) associations of patient factors, physician factors, and the country of care (or health care system) factor from our balanced factorial design, we used an analysis of variance (ANOVA) for both dichotomous and continuous outcomes. The error term was the residual after specifying the full factorial model (pure error due to replication) with 192 degrees of freedom. While logistic regression might have been more appropriate (technically) for dichotomous outcomes, we used ANOVA for several reasons: (1) the full factorial model could not be specified using logistic regression due to data sparseness (with only 2 observations in each of the 16 × 3 × 4 cells; there were likely to be many cells with no data when considering a dichotomous outcome; as our sample size was 2 × 16 × 3 × 4= 384); (2) this Fisherian regression was equivalent to discriminant analysis11; (3) the models were equivalent due to the Central Limit Theorem; (4) comparison of P values from a full factorial ANOVA model, an ANOVA model with main effects and 2-way interactions, and a logistic regression model with main effects and 2-way interactions produced similar values; and (5) ANOVA results appeared to be more easily understood.

Since we were primarily interested in the main effect due to country of care (or health care system) and the 2-way interactions of country and patient/physician factors and since there were no significant main effects due to patient race for the 2-country analysis (United Kingdom and United States), we considered a full factorial model including patient age, gender, and socioeconomic status; audio gender of the unseen physician; physician gender and experience; and country of care. The only exception was when we considered 2-way interactions of country of care and patient race, for which we restricted the analysis to 2 countries using the full factorial model specified above with the addition of a factor for patient race. We found a statistically significant (P < .05) effect due to country; thus, we employed Tukey's studentized range multiple comparisons procedure12 to determine which countries were significantly different. Given our sample size of 384, we had 80% power to detect an absolute difference of 17% between the means of 3 groups (eg, 20% of physicians from country A versus 37% of physicians from country B would ask questions about alcohol).

RESULTS

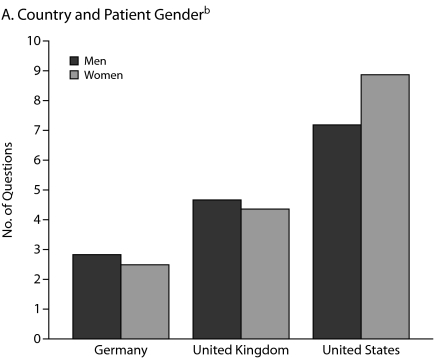

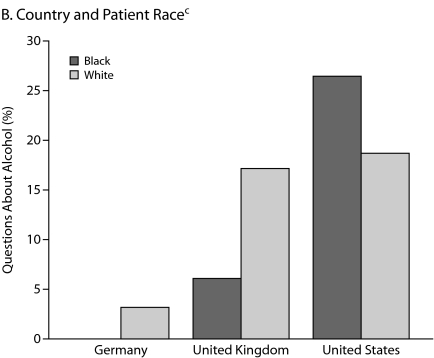

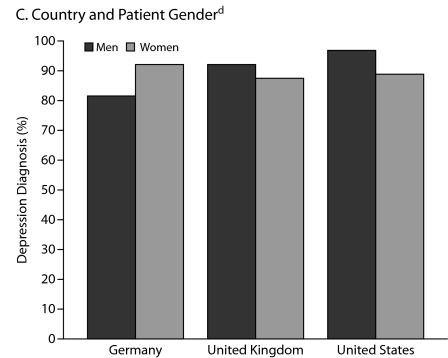

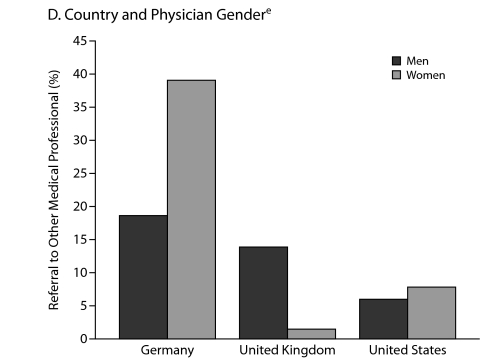

The response rates were similar in the 3 countries: 65.0% in Germany, 64.9% in the United States, and 59.6% in the United Kingdom. Table 3 (information gathering and diagnosis) and Table 4 (management) summarize the main effect due to country of care (or health care system). The P value from the ANOVA is given, along with Tukey's multiple comparisons (means with a common letter superscript were not significantly different at the .05 level). Significant interactions are indicated by a letter in the last column of Tables 3 and 4 and presented graphically in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Diagnostic Strategies (information gathering, percent with a depression diagnosis, and certainty of depression diagnosis) by Country (health care system)

| Country1 |

|||||

| Diagnostic Strategies | Germany | United Kingdom | United States | P Value | Significant Interactions2 |

| Information gathering | |||||

| No. of questions | 2.6a | 4.5b | 8.0c | < .0001 | A |

| Questions about, % | |||||

| Pathology | 28.9a | 60.9b | 74.2c | < .0001 | |

| Medical history | 23.4a | 39.1b | 64.0c | < .0001 | |

| Pain | 23.4a | 24.2ab | 37.5b | .0243 | |

| Alcohol | 3.1a | 11.7a | 22.7b | < .0001 | B |

| Psychological state | 25.0a | 45.3b | 52.3b | < .0001 | |

| Social situation | 37.5a | 47.7ab | 54.7b | .0209 | |

| General | 32.8a | 52.3b | 69.5c | < .0001 | |

| Complete physical, % | 46.9a | 11.7b | 39.0a | < .0001 | |

| Depression diagnosis, % | 86.7a | 89.8a | 92.3a | .2361 | C |

| Certainty of depression diagnosis, % | 68.9ab | 65.4a | 74.0b | .0578 | |

Means (by country) with the same superscript letter cannot be considered statistically different at the .05 level using Tukey's multiple comparisons.

Significant 2-way interactions of country and another design variable that modify the country effect are indicated in the last column; the letter refers to the panel of Figure 1 wherein the interaction is plotted.

Table 4.

Management Strategies (prescription, referral, lifestyle advice, and time to follow-up) of a Patient With Symptoms Strongly Suggestive of Depression by Country (health care system)

| Country1 |

|||||

| Management Strategies | Germany | United Kingdom | United States | P Value | Significant Interactions2 |

| Antidepressant prescription, % | 25.8ab | 18.0a | 33.6b | .0241 | |

| Referral, % | |||||

| Mental health professional | 28.9a | 5.5b | 18.0a | < .0001 | |

| Other medical professional | 28.9a | 7.8b | 7.0b | < .0001 | D |

| Lifestyle advice, % | 1.3a | 1.4a | 1.7b | < .0001 | |

| Exercise | 13.3a | 6.2b | 28.9a | < .0001 | |

| Alcohol | 1.6a | 7.8ab | 9.4b | .0321 | |

| Diet | 6.2a | 7.0a | 12.5a | .1050 | |

| Time to next appointment (days) | 7.6a | 11.0b | 16.4c | < .0001 | |

Means (by country) with the same superscript letter cannot be considered statistically different at the .05 level using Tukey's multiple comparisons.

Significant 2-way interactions of country and another design variable that modify the country effect are indicated in the last column; the letter refers to the panel of Figure 1 wherein the interaction is plotted.

Figure 1.

Significant 2-Way Interactions of Country and Other Design Factorsa

aThe panel letter (A–D) reflects the corresponding letter from the last column of Tables 3 and 4.

bP = .0342.

cP = .0476.

dP = .0251.

eP = .0007.

Information Gathering

American physicians asked more questions than their European counterparts. The significant 2-way interaction of country of care and patient gender (P = .0342, Figure 1A) was due to the propensity of American physicians to ask more questions of women, while European physicians asked more questions of men. Since American physicians were more likely to ask the most questions, they were also the most likely to ask about pathology, medical history, pain, alcohol use, and the patient's psychological state and social situation, as well as more general questions. German physicians asked the fewest questions and were least likely to inquire about these items. The main effect due to country of care related to questions about alcohol use was modified by a 2-way interaction of country and patient race (P = .0476, Figure 1B), where British and American physicians were equally likely to ask white patients about alcohol; if the patient was black, British physicians were less likely to ask him/her about alcohol. British physicians were least likely to want to perform a complete physical (11.7%) compared to American (39.0%) or German (46.9%) physicians.

Diagnosis

The vast majority of physicians (89.6%) gave depression as one of their diagnoses. While there was no main effect due to country (P = .2361, Table 3), there was a significant 2-way interaction of country of care and patient gender (P = .0251, Figure 1C). German physicians were more likely to diagnose depression in women, but British and American physicians were more likely to diagnose depression in men. American physicians were the most certain of their depression diagnosis, and British general practitioners were the least certain of their depression diagnosis.

Clinical Management

British physicians were least likely to prescribe an antidepressant or to refer the patient to a mental health professional (Table 4). In addition to variations in referrals to a mental health professional by country of care, there was also variation in the type of professional referral. In Germany, 19 of the 37 (51%) physician referrals to a mental health professional were to a neurologist,13 14 (38%) were to a psychiatrist, and 4 (11%) were to a therapist. In the United Kingdom, of the 7 referrals to a mental health professional, 4 (57%) were to a therapist and 3 (43%) were to a psychiatric practice nurse. In the United States, of the 23 referrals to a mental health professional, 13 (57%) were to a therapist, 5 (22%) were to a psychiatrist, and 5 (22%) were to a psychologist.

There was also considerable variation in the type of antidepressant medication prescribed in the 3 countries (Table 4). Of the 33 antidepressant prescriptions in Germany, 11 (33%) were for St John's wort and/or valerian, 8 (24%) were for a tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), 6 (18%) were for a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI)/serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI), 7 (21%) were unspecified, and 1 (3%) was for a benzodiazepine. In the United Kingdom, of the 23 antidepressants prescribed, 18 (78%) were for a SSRI/SNRI, 2 (9%) were for a TCA, and 3 (13%) were unspecified. In the United States, of the 42 antidepressants prescribed, 38 (90%) were for a SSRI/SNRI and 4 (10%) were for a TCA.

There was a significant 2-way interaction of country of care and physician gender when considering referral to another medical (non–mental health) professional (P = .0007, Figure 1D). Female German physicians were more likely to refer to another medical professional than were male German physicians, but male British physicians were more likely to refer to another medical professional than were female British physicians, with little variation by gender seen for American physicians. American physicians gave more lifestyle advice (including more advice about exercise).

With regard to follow-up, 1 British and 1 American physician reported no need to see the patient again. For those suggesting a follow-up visit, the German physicians would, on average, see the patient again in about a week, while their American counterparts were content to wait more than 2 weeks (P < .0001, Table 4).

DISCUSSION

We found considerable variation by country (and health care system) in the diagnosis and management of a patient with symptoms strongly suggestive of depression. German physicians were more likely to diagnose depression in women than were British and American physicians, who were more likely to diagnose depression in men. This finding may be attributable to differences in the content of medical education among the 3 countries. Medical education has recently emphasized that depression may be as common in men as in women and is frequently underdiagnosed.14 The certainty of a depression diagnosis, which was highest in the United States, may be important, as we have found that certainty drives test ordering, prescriptions, and referrals.15,16 Physicians in the United States are significantly more likely to prescribe antidepressants than are British physicians, which may be a response to several influences: direct-to-consumer advertising, defensive medical practices, or rewards for doing more, in contrast to general practitioners in the United Kingdom who are rewarded more for doing less. Between-country differences related to which professional the patient would be referred to may reflect variation in the availability of different types of practitioners in the countries studied (see Table 1). American physicians may ask more questions of patients secondary to their need to explore more options to avoid downstream complications. German physicians asked fewer questions and offered less lifestyle advice, possibly because of the shorter mean time allocated for appointments: 5.5 minutes was allocated for a routine appointment in Germany compared to 9.7 minutes in the United Kingdom and 18.1 minutes in the United States.17 Although German physicians were also the most likely of the 3 groups to do a complete physical, the definition of a complete physical varied by country (as German physicians have 12.5 minutes allocated for a complete physical versus 19.8 minutes in the United Kingdom and 36.0 minutes in the United States).17 Variability in when patients would be seen for a follow-up visit may also be a function of the mean time allocated for a visit—having a shorter time allocated for a visit in Germany may result in more frequent visits.

Our research has both strengths and limitations. Well-designed and carefully conducted experiments can provide unconfounded estimates and permit cause-and-effect statements. Use of a random community-based sample rather than a convenience sample at a local medical institution or professional conference enhances the generalizability of our results. Because all physician subjects encountered exactly the same patient and constellation of symptoms of depression, any differences among the 3 countries cannot be attributed to variation among patients or the seriousness of the symptoms. While an experiment may have excellent internal validity, there is always a threat to external validity (eg, a physician may act differently with the vignette patient than with real patients seen in his/her everyday practice). We deliberately attempted to strengthen external validity by (1) specifically instructing the physician subjects to respond as they would with a real patient in their practice or surgery, (2) having physicians view the vignettes in the context of their clinic practice rather than at home or at a professional meeting so it is likely that they saw real patients before and after the vignettes, and (3) conducting role-play sessions and field testing with experienced clinicians to ensure that the vignettes were clinically authentic. When asked how typical the vignette patient was compared to their own patients, 81.2%, 80.3%, and 85.2% of German, British, and American physicians, respectively, thought that the presentation was either very or reasonably typical. There is evidence of a secular decline in response rates for social surveys, especially those attempting to recruit physicians, which now run around 50%. Diligent efforts were made to achieve the response rates for our study (60%–65%). However, there is always a possibility that the generalizability of our results may be threatened by selection bias. Generalizability to national samples may be poor if the selected sampling areas do not reflect the nation as a whole. Also, it is impossible to separate any cultural variation from country or health care system variation.

CONCLUSION

There are significant differences between countries (and health care systems) in the way primary care physicians diagnose and manage patients with depression, even when the same “patients” present exactly the same symptoms strongly suggestive of the disease. Such variations may result from international differences in (1) medical education, (2) attitudes toward patients, (3) the availability of other practitioners, and (4) different methods of reimbursement. Whether similar differences in diagnosis and management occur with other illnesses, like arthritis and cancer, remains to be investigated. Some of the reported international differences in disease rates and health care outcomes may be a result of differences in the manner in which physicians in different countries (and health care systems) diagnose and manage the same symptoms of disease.

Potential conflicts of interest: Dr Stern is an employee of the Academy of Psychosomatic Medicine, has served on the speaker's board of Reed Elsevier, is a stock shareholder in WiFiMD (Tablet PC), and has received royalties from Mosby/Elsevier and McGraw Hill. Dr Arber has received grant/research support from the National Institute of Aging. Drs Link, Adams, Siegrist, Knesebeck, and McKinlay and Mss Piccolo and Marceau report no conflicts of interest related to the subject of this article.

Funding/support: This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (grant no. AG16747), Bethesda, Maryland.

Disclaimer: The content of this article is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Aging or the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.World Health Organization, Department of Measurement and Health Information. Death and DALY estimates for 2004 by cause for WHO Member States, Table 6. http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/estimates_country/en/index.html. Accessed July 8, 2011.

- 2.Demyttenaere K, Bruffaerts R, Posada-Villa J, et al. WHO World Mental Health Survey Consortium. Prevalence, severity, and unmet need for treatment of mental disorders in the World Health Organization World Mental Health Surveys. JAMA. 2004;291(21):2581–2590. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.21.2581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Angermeyer M, Anthony JC, et al. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions of mental disorders in the World Health Organization's World Mental Health Survey Initiative. World Psychiatry. 2007;6(3):168–176. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.World Health Organization. Mental Health Atlas 2005. Geneva, Switzerland: Department of Mental Health and Substance Abuse, World Health Organization; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.McKinlay J, Link C, Marceau L, et al. How do doctors in different countries manage the same patient? results of a factorial experiment. Health Serv Res. 2006;41(6):2182–2200. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2006.00595.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.von dem Knesebeck O, Bönte M, Siegrist J, et al. Country differences in the diagnosis and management of coronary heart disease: a comparison between the US, the UK and Germany. BMC Health Serv Res. 2008;8(1):198. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blendon RJ, Schoen C, DesRoches C, et al. Common concerns amid diverse systems: health care experiences in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood). 2003;22(3):106–121. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.22.3.106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blendon RJ, Schoen C, DesRoches CM, et al. Confronting competing demands to improve quality: a five-country hospital survey. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004;23(3):119–135. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.23.3.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoen C, Osborn R, Huynh PT, et al. Primary care and health system performance: adults’ experiences in five countries. Health Aff (Millwood) 2004 doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.w4.487. (suppl web exclusives):W4-487–503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Fourth Edition, Text Revision. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kendall M, Stuart A, Ord JK. The Advanced Theory of Statistics. 4th ed. Vol. 3. New York, NY: Macmillan; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller RG. Simultaneous Statistical Inference. 2nd ed. New York, NY: Springer; 1981. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Arolt V. Psychiatrische Erkrankungen. In: Schwartz FW, Badura B, Busse R, et al., editors. Das Public Health Buch: Gesundheit und Gesunheit Wesen. Munich, Germany: Urban & Fischer; 2003. pp. 605–613. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cochran SV, Rabinowitz FE. Men and Depression: Clinical and Empirical Perspectives. San Diego, CA: Academic Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lutfey KE, Link CL, Grant RW, et al. Is certainty more important than diagnosis for understanding race and gender disparities? an experiment using coronary heart disease and depression case vignettes. Health Policy. 2009;89(3):279–287. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2008.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lutfey KE, Link CL, Marceau LD, et al. Diagnostic certainty as a source of medical practice variation in coronary heart disease: results from a cross-national experiment of clinical decision making. Med Decis Making. 2009;29(5):606–618. doi: 10.1177/0272989X09331811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Konrad TR, Link CL, Shackelton RJ, et al. It's about time: physicians’ perceptions of time constraints in primary care medical practice in three national healthcare systems. Med Care. 2010;48(2):95–100. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181c12e6a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]