Abstract

Objective

To describe models used in successful clinical initiatives to improve the quality of palliative care in critical care settings.

Data Sources

We searched the MEDLINE database from inception to April 2010 for all English language articles using the terms “intensive care,” “critical care,” or “ICU” and “palliative care”; we also hand-searched reference lists and author files. Based on review and synthesis of these data and the experiences of our interdisciplinary expert Advisory Board, we prepared this consensus report.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

We critically reviewed the existing data with a focus on models that have been used to structure clinical initiatives to enhance palliative care for critically ill patients in intensive care units and their families.

Conclusions

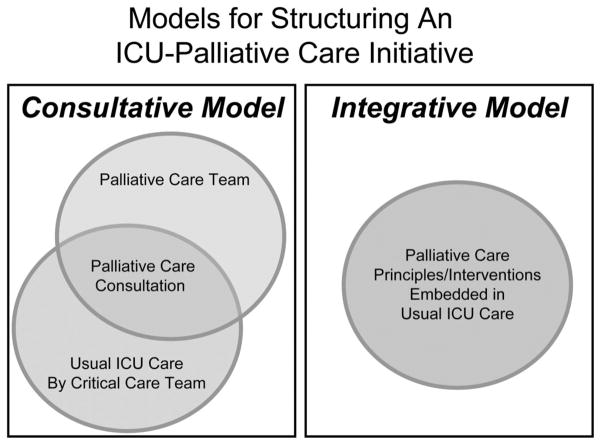

There are two main models for intensive care unit–palliative care integration: 1) the “consultative model,” which focuses on increasing the involvement and effectiveness of palliative care consultants in the care of intensive care unit patients and their families, particularly those patients identified as at highest risk for poor outcomes; and 2) the “integrative model,” which seeks to embed palliative care principles and interventions into daily practice by the intensive care unit team for all patients and families facing critical illness. These models are not mutually exclusive but rather represent the ends of a spectrum of approaches. Choosing an overall approach from among these models should be one of the earliest steps in planning an intensive care unit–palliative care initiative. This process entails a careful and realistic assessment of available resources, attitudes of key stakeholders, structural aspects of intensive care unit care, and patterns of local practice in the intensive care unit and hospital. A well-structured intensive care unit–palliative care initiative can provide important benefits for patients, families, and providers.

Keywords: intensive care, critical care, palliative care

Palliative care focuses on complex pain and symptom management, communication about care goals, alignment of treatments with patient values and preferences, transitional planning, and support for the family. Increasingly, this type of care is seen as an essential component of comprehensive care for patients with critical illness, including those receiving aggressive intensive care therapies (1–4). Although prior literature has illuminated why palliative care should be integrated in the intensive care unit (ICU) and which aspects of ICU palliative care could be improved, guidance on how this might be effectively accomplished in practice remains limited. This article focuses on practical approaches to ICU palliative care, which extend across a spectrum that is defined at either end by models we refer to as “consultative” and “integrative.” We describe key features of these models, which can be combined; discuss their advantages and disadvantages; provide examples of initiatives using the different models; address the process of choosing an appropriate model; and review outcomes of effective integration of palliative care in the ICU setting.

This article does not report a research study involving human or animal subjects. As such, no approval was required from the Institutional Review Board.

Main Models for Palliative Care Integration in the ICU

There are two main models for ICU–palliative care integration. One, the “consultative model,” focuses on increasing the involvement and effectiveness of palliative care consultants in the care of ICU patients and their families, particularly those patients identified as at highest risk for poor outcomes (e.g., death in the hospital or early postdischarge period; severe functional and/or cognitive impairment). The second approach, the “integrative model,” seeks to embed palliative care principles and interventions into daily practice by the ICU team for all patients and families facing critical illness. These models are shown in Figure 1 and described more fully subsequently.

Figure 1.

This figure illustrates the two main models for integration of palliative care in the intensive care unit (ICU). The “consultative model” focuses on increasing the involvement and effectiveness of palliative care consultants in the care of ICU patients and their families. The “integrative model” seeks to embed palliative care principles and interventions into daily practice by the ICU team for all patients and families facing critical illness.

Consultative Model: Palliative Care Consultation in the ICU

Expert palliative care through a consultation service is currently available at the majority of US hospitals, including >75% of large hospitals, all Veterans’ Affairs medical centers, and an increasing number of smaller and community-based hospitals (5). The National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (www.nationalconsensusproject.org), a consortium of the nation’s leading palliative care organizations, has developed and updated Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care to describe the core elements of clinical palliative care programs (6); these standards were adopted by the National Quality Forum (www.qualityforum.org) within its Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care (7) and recently operationalized by the Center to Advance Palliative Care (www.capc.org) (8). Qualified physicians can become certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine as subspecialists in hospice and palliative medicine through any of ten cosponsoring boards in the American Board of Medical Specialties. Palliative care nurses are certified by the National Board for Certification of Hospice and Palliative Nurses (www.nbchpn.org).

Over two decades ago, clinicians at Detroit Receiving Hospital described efficiencies and savings in critical care resource use measured by reduction of Therapeutic Intervention Severity Scores, bed costs, and lengths of ICU and hospital stay with referrals of ICU patients who were “not expected to survive hospitalization” by the primary team to a “Comprehensive Supportive Care Team” (9, 10). This specialized team, including an advanced practice nurse as the main provider in collaboration with a rotating attending physician, accepted primary care responsibility for patients, who were moved to general medical/surgical wards for implementation of the supportive care plan (9, 10). Subsequent reports from the same institution and others describe additional initiatives involving proactive referrals by ICUs to the hospital’s palliative care consultation service (11–14). Features of these initiatives are summarized in Table 1. Typically, the consultative model for integrating palliative care in the ICU addresses a subset of ICU patients at highest risk for poor outcomes rather than all patients in the ICU. Many successful initiatives using this consultative model have identified clinical “triggers” for palliative care consultation. Even if consultation is triggered only for specific groups of ICU patients, however, the “ripple effect” resulting from an increased presence of palliative care consultants in the ICU may stimulate referrals for other patients and help to enculturate palliative care within the usual care of the ICU.

Table 1.

Palliative care consultation model for the intensive care unit

| Reference | Triggering Criteria | Consultants/Team | Consultation/Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|

| Campbell et al (11) |

|

|

Proactive consultation with

|

| Campbell et al (32) |

|

|

|

| Billings et al (12) | (Regular presence of palliative care consultation service in ICU, leading to referrals; no specific patient criteria) |

|

|

| Norton et al (13) |

|

|

|

| O’Mahony et al (14) |

|

|

|

ICU, intensive care unit; MV, mechanical ventilation; APN, advanced practice nurse; SW, social worker; PC, palliative care.

Triggering criteria

Triggers for palliative care consultation can include baseline patient characteristics (e.g., pre-existing functional dependence, age >80 yrs, advanced-stage malignancy), selected acute diagnoses (e.g., global cerebral ischemia after cardiac arrest, prolonged dysfunction of multiple organs), and/or healthcare use criteria (e.g., specified duration of ICU treatment, referral for tracheotomy or gastrostomy, decision to forgo life-sustaining therapy such as renal replacement). For pediatric ICUs, extreme prematurity, severe traumatic brain injury, and Trisomy 13 are illustrative trigger criteria. For some ICUs, the trigger is the judgment of the critical care physician that a poor outcome is likely or the failure of initial ICU efforts to address palliative care needs of the patient or family. Triggers can be used to initiate a full palliative care consultation or a preliminary review with a palliative care clinician to determine whether such a consultation is needed (13). In some ICUs, a palliative care clinician joins ICU rounds on a regular basis to help with timely identification of patients and families who could benefit from expert palliative care input (12, 14).

Consultants

The palliative care professionals who provide consultative service vary by institution. In some ICUs, the service is provided by a single consultant, often an advanced practice nurse, whereas in others, consultations are performed by an interdisciplinary team of palliative care clinicians, including a physician, nurse, social worker, psychologist, and/or chaplain. A child life specialist may join a pediatric palliative care consultation team. The National Consensus Project Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care and the Consensus Recommendations on Hospital Palliative Care Programs from the Center to Advance Palliative Care have established standards for palliative care services, including their composition and availability (6, 8). Some hospitals do not yet have palliative care consultation services but do have clinical ethics consultants who can assist in meeting certain palliative care needs of ICU patients and families such as discussion of appropriate care goals and resolution of conflict over such goals (15, 16).

Scope of consultation

Using a synthesis of empirical evidence and expert consensus, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care End-of-Life Peer Workgroup identified seven key domains of ICU palliative care: 1) patient- and family-centered decision making; 2) communication within the team and with patients and families; 3) continuity of care; 4) emotional and practical support for patients and families; 5) symptom management and comfort care; 6) spiritual support for patients and families; and 7) emotional and organizational support for ICU clinicians (17). These domains map to those addressed by the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care in its Clinical Practice Guidelines (6), which are premised on the “expectation … that palliative care services delivered by all healthcare professionals within the scope of their disciplines and care settings will rise to the level of ‘best practice’ to meet the needs of their patients” (p 8). A comprehensive palliative care consultation includes all of these domains. In the ICU, however, palliative care consultants may be asked to focus on a narrower range of issues; most common among these are goal setting, withdrawal of unwanted life-prolonging therapies, do not resuscitate designation, conflict resolution, and transitional planning. Expertise in palliative care does not substitute for primary intensive care in any area but may be helpful to the critical care team for complex or refractory problems across the domains of palliative care, just as expert input enhances primary intensive care in cardiology, nephrology, infectious diseases, or other relevant fields. Depending on the care model of the ICU and the relationship between the critical care and palliative care teams, responsibility for implementation of consultants’ recommendations may remain solely with the ICU team or be shared with or delegated to the palliative care consultants (e.g., palliative care consultants might join or lead ICU family meetings to establish goals of care).

Integrative Model: Integration of Palliative Care in Daily ICU Practice

Because rates of mortality and other unfavorable outcomes are high in ICUs and virtually all critically ill patients and their families have palliative needs, many critical care professionals and others believe that the critical care team itself should integrate palliative care principles into daily ICU practice. An initiative starting from this premise emphasizes internal efforts to enhance systems of care as well as ICU clinicians’ knowledge and skills in palliative care; Table 2 provides examples. Changes in the ICU’s routine typically affect all patients but can be focused on specific subgroups, like those targeted by triggering criteria for palliative care consultation (examples in Table 1).

Table 2.

ICU integration of palliative care in daily practice: Examples of initiatives

| Initiative/Reference | Main Components |

|---|---|

| “Intensive Communication Intervention”/Lilly et al (27) |

|

| “Transformation of the ICU” (“TICU”) Multi-ICU Performance Improvement Initiative Using “Care & Communication Bundle”/Nelson et al (28) |

|

| Veterans’ Integrated Service Network 3 Multi-ICU Palliative Care Initiative/Nelson et al (25) |

|

| Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care Demonstration Project—Integrating Palliative Medicine and Critical Care in a Community Hospital/Ray et al (47) |

|

| Robert Wood Johnson Foundation/Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care Demonstration Project—Integrating Palliative Care into the Surgical and Trauma Intensive Care Unit/Mosenthal et al; Mosenthal and Murphy (23, 30) |

|

| Quality Improvement Intervention in ICUs at a University-Based, Urban Hospital/Curtis et al (48) |

|

ICU, intensive care unit.

Knowledge and skills

Although many ICU clinicians have experience in addressing certain palliative care needs of patients and families, few have been specifically trained to provide this type of care. Such training is valuable, however, for clinical challenges like managing multiple symptoms in the context of organ failure and adverse effects from first-line analgesic therapy, and communicating with families about limitation of intensive care therapies. In addition, these areas are explicitly included among competencies for critical care physicians that were recommended by a Task Force representing the Society of Critical Care Medicine, American College of Chest Physicians, American Thoracic Society, American Board of Internal Medicine, and the Association of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine Program Directors (16). Thus, educational efforts targeted to physicians, nurses, and other members of the critical care team are a key component of initiatives to strengthen internal capability for ICU palliative care. Some ICUs have developed or accessed palliative care specialists and other experts in their own institution as educators. Critical care professionals can also attend national programs with relevant content such as the End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC)–Critical Care training program (18), the Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care program (19), and postgraduate courses at annual meetings of societies representing critical care professionals. A team of intensivists and palliative care experts has created and piloted a new Critical Care Communication skills program (“C-3”) for fellows training in critical care (20); curricular modules used in this course will be available online (21). An ongoing initiative in Veterans’ Integrated Service Network 3 includes a novel program of communication skills training for ICU staff nurses to enhance their participation in interdisciplinary meetings with families of critically ill patients.

Systems of care

Dramatic successes in ICU patient safety have been achieved by recent ICU initiatives emphasizing systematization of work processes to achieve the targeted objectives (22). This approach is applicable to palliative care integration by ICUs, which also requires design and implementation of effective systems to support best clinical practice. Like the checklists and other technical supports that have been essential to reduction of catheter-related bloodstream infections, simple tools can facilitate assessment and management of palliative needs of ICU patients and families. Some ICUs have implemented comprehensive systems incorporating multiple tools to ensure integration of palliative care. For example, a trauma ICU implemented a multifaceted intervention including palliative care assessment of all patients within 24 hrs followed by a family meeting within 72 hrs and, for patients receiving care focused exclusively on comfort, a palliative care order set and clinical practice guidelines for ventilator withdrawal (23). Other ICUs have developed a standardized order set for withdrawal of mechanical ventilation in patients who are not expected to survive (“palliative” or “terminal” extubation) (24). A Family Meeting Planner, Guide for Families in booklet form, and Documentation Template comprise a tool kit that can be used along with other strategies to improve the frequency and quality of ICU family meetings (25, 26). The new IPAL-ICU Project, supported by the National Institutes of Health and the Center to Advance Palliative Care, is designed to serve as a comprehensive, online repository of practical resources for improving palliative care in the ICU, including prototypes of selected tools that can be adapted and refined for use by specific ICUs (21).

Several initiatives have focused on improving the ICU’s performance of specific palliative care processes. For example, Lilly et al (27) used an “intensive communication intervention” involving pro-active family meetings within 72 hrs of ICU admission for patients for whom the ICU attending physician predicted a length of ICU stay >5 days, risk of death >25%, or potentially irreversible change in function precluding eventual return to home; meetings included the attending intensivist, house staff, ICU nurse, family, and patient whenever possible. A before–after comparison showed a 1-day reduction in median length of ICU stay for patients receiving this intervention and shorter time to consensus about appropriate goals of care (27). A new “bundle” of ICU–palliative care process measures provided the basis for a large-scale performance improvement initiative by ICUs in the Transformation of the ICU Project by the Voluntary Hospital Association, Inc (28) and for an ongoing initiative by ICUs in Veterans’ Integrated Service Network 3 (25). Processes measured by this tool include identification of the patient’s surrogate medical decision maker and resuscitation status; offers of emotional, practical, and spiritual support; and an interdisciplinary family meeting to discuss the patient’s condition, prognosis, and goals of care (29) (Table 3). Performance of these care processes is evaluated by medical record documentation and is reviewed with ICU clinicians as feedback for performance improvement.

Table 3.

Intensive Care Unit Palliative Care Processes in the Voluntary Hospital Association, Inc “Care and Communication Bundle”a

| By ICU day 1 |

| Identify medical decisionmaker |

| Address advance directive status |

| Address resuscitation status |

| Distribute family information leaflet |

| Assess pain regularly |

| Manage pain optimally |

| By ICU day 3 |

| Offer social work (emotional/practical) support |

| Offer spiritual support |

| By ICU day 5 |

| Conduct interdisciplinary family meeting |

ICU, intensive care unit.

Processes are to be performed no later than the specified day in the ICU; day of ICU admission is day 0. Detailed criteria have been developed for evaluation of performance (28).

Pros and Cons of the Main Models

Both models we describe for assimilating palliative care in the ICU have advantages and disadvantages, which we summarize in Table 4. Given the challenges inherent in the individual models, a combined approach using elements from both models may be optimal and has been described for a medical ICU (12) and a surgical ICU (30). This hybrid approach requires availability of palliative care consultants, commitment by the critical care team to strengthening internal capability for palliative care delivery, and a willingness to collaborate.

Table 4.

Pros and cons of the main models for integrating palliative care in the intensive care unit

| Model | Consultation by Palliative Care Service | Integration by Critical Care Team in Daily ICU Practice |

|---|---|---|

| Advantages |

|

|

| Disadvantages |

|

|

ICU, intensive care unit.

Choosing an Approach

Choosing an overall approach from among these models should be one of the earliest steps in planning an ICU–palliative care initiative. This process will entail a careful and realistic assessment of available resources, attitudes of key stakeholders, structural aspects of ICU care, and patterns of local practice in the ICU and hospital. For an initiative based mainly on the consultative model, the palliative care service must have sufficient staffing to meet increased demand from the ICU, knowledge and skill to address unique needs of critically ill patients and their families, and a commitment to support structures, processes, and plans of care established by the critical care team. This approach also requires a reasonable level of receptivity on the part of ICU clinicians to input from palliative care experts. Often, the critical care nurses are the earliest team members to embrace palliative care consultation, with intensive care physicians taking longer to acknowledge the need for or value of expert consultation in this area; in time, the nurses’ enthusiasm usually spreads across disciplines, especially if an ICU physician with leadership responsibility provides support and direction. One way to evaluate and enhance the readiness of both the palliative care and ICU teams for collaboration is to invite participation by palliative care consultants in ICU patient care rounds, for example, several days each week, at least for a trial period. Although time-consuming for the consultants, their presence on rounds provides a valuable opportunity to demonstrate the feasibility, acceptability, and benefits of regular collaboration and to build mutual trust for use of the consultative model in an ongoing initiative. This trust is enhanced by acknowledgment from palliative care consultants of the value of life-sustaining treatments for appropriate patients with severe illness, even some with underlying chronic and life-limiting illness. It is also strengthened by education of ICU clinicians about the value of early integration of palliative care during critical illness, even when intensive care therapies are to continue.

Success of the integrative model will require a strong and sustained commitment from ICU physicians and nurses to strengthen their knowledge, skills, and systems for incorporating palliative care into daily practice. If a social worker, psychologist, or chaplain is assigned or accessible to the unit, this individual can help to facilitate palliative care integration. In addition, this approach depends on a supportive culture in which all disciplines on the critical care team endorse a central role for palliative care principles within regular ICU practice. In planning successful initiatives to improve patient safety, interdisciplinary discussions in which participants identify possible barriers to implementation and suggest strategies for overcoming barriers have been helpful in building a culture that is conducive to improvements in care (31). Presentation of baseline data related to palliative care performance (e.g., data on adherence to important processes of care such as clinician meetings with families; on family psychological well-being; or on relevant aspects of resource use) highlights opportunities for improvement. A meeting of this kind may similarly help those planning a palliative care initiative both to evaluate and to expand the ICU’s capabilities for implementation using an integrative approach.

In the end, most ICUs will choose a combined approach. The appropriate “balance” between activities by palliative care consultants and those by clinicians on the critical care team needs to be determined for each specific ICU, even within a single institution, and may shift over time depending on a range of factors, including the results of early efforts, changes in resources available from the palliative care service, and/or increasing internal capability of the ICU for palliative care delivery. A project team representing key stakeholders in an ICU–palliative care initiative (e.g., critical care and palliative care physician and nurse leaders; members of other relevant disciplines such as social work and chaplaincy; hospital leadership) is in the best position to set this balance and adjust it as needed over time.

Impact of Palliative Care Integration in the ICU

A well-structured initiative to enhance palliative care in the ICU can provide important benefits for patients, families, and providers, as summarized in Table 5. Several studies have shown that palliative care consultation for patients meeting trigger criteria and proactive communication interventions by palliative care or ethics consultants or by the ICU team are associated with reductions in use of non-beneficial ICU treatments, length of ICU stay, and/or conflict over care goals (11, 13, 15, 27, 32, 33). The primary mechanism for efficiencies in use is earlier clarification of patients’ preferences and consensus in decision making, allowing timely implementation of an appropriate plan of care. This explains how ICUs have achieved these favorable outcomes without increasing ICU mortality. The use of a brochure about the ICU increased levels of satisfaction and comprehension of relevant medical information among families (34) and an intervention combining proactive clinician meetings and a brochure for families of patients dying in the ICU reduced family anxiety, depression, and posttraumatic stress disorder 3 months after the patient’s death (35). Systematic assessment improved ratings of pain, increased therapeutic adjustments of analgesics (escalation and de-escalation), and decreased the duration of mechanical ventilation (36–38). Further research is needed to evaluate impact on other outcomes including job satisfaction of intensive care clinicians.

Table 5.

Benefits of integrating palliative care in the intensive care unit

| Outcome | Selected Relevant Studies | |

|---|---|---|

| ↓ | Intensive care unit/hospital length of stay | Campbell et al (11); Campbell et al (32); Norton et al (13); Curtis et al (48) |

| ↓ | Use of nonbeneficial treatments | Campbell et al (11); O’Mahony et al (14); Pierucci et al (33) |

| ↓ | Duration of mechanical ventilation | Payen et al (38) |

| ↑ | Family satisfaction/comprehension | Azoulay et al (34) |

| ↓ | Family anxiety/depression, posttraumatic stress disorder | Lautrette et al (35) |

| ↓ | Conflict over goals of care | Lilly et al (27) |

| ↓ | Time from poor prognosis to comfort-focused goals | Campbell et al (11) |

| ↑ | Symptom assessment/patient comfort | Erdek and Pronovost (36); Chanques et al (37) |

↓ decreased; ↑, increased.

CONCLUSION

More patients die in ICUs than anywhere else in US hospitals (39). Half a million Americans die in or after ICU treatment each year (39), whereas many others remain chronically critically ill with severe functional and cognitive impairments. Over the last decade, well-conducted research has contributed important evidence of opportunities to improve palliative care in ICUs and of effective strategies for this purpose. Practical application of this evidence has lagged behind, as shown by recent data demonstrating persistent problems in symptom management (40), communication between clinicians and families and within clinical teams (41, 42), family experience (43, 44), and burnout and moral distress among ICU physicians and nurses (45, 46). To address this “quality gap” between knowledge and practice, the National Institute on Aging and the Center to Advance Palliative Care have sponsored the new “IPAL-ICU” Project to Improve Palliative Care in the ICU. This program, under the aegis of an interdisciplinary Advisory Board composed of national experts in the field, will disseminate tools shared by successful programs as well as a wide range of other resources, including technical assistance monographs such as the present article. The staggering rise in the cost of health care generally and ICU care specifically obligates all critical care professionals to explore the efficiencies that palliative care can provide along with other benefits without increasing ICU or hospital mortality rates. This process begins with consideration of the structure of a palliative care initiative that can best meet the needs of ICU patients, their loved ones, clinicians, and the hospital either by expanding the involvement of expert palliative care consultants, the internal capabilities of the ICU for palliative care delivery, or both. As discussed in more detail in this article, our recommendations for structuring such an initiative are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Recommendations for choosing a model to structure an intensive care unit–palliative care initiative

|

ICU, intensive care unit.

Acknowledgments

The IPAL-ICU Project is based at Mount Sinai School of Medicine with support from the National Institute on Aging (K07 Academic Career Leadership Award AG034234 to Dr. Nelson) and the Center to Advance Palliative Care.

We are grateful to Dr. Diane E. Meier for her counsel to and support of the IPAL-ICU Project and her insightful comments on the manuscript.

Footnotes

See also p. 1904.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Truog RD, Campbell ML, Curtis JR, et al. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: A consensus statement by the American College [corrected] of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:953–963. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lanken PN, Terry PB, Delisser HM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society clinical policy statement: Palliative care for patients with respiratory diseases and critical illnesses. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;177:912–927. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200605-587ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Selecky PA, Eliasson CA, Hall RI, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care for patients with cardiopulmonary diseases: American College of Chest Physicians position statement. Chest. 2005;128:3599–3610. doi: 10.1378/chest.128.5.3599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, et al. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU/Statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:770–784. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Goldsmith B, Dietrich J, Du Q, et al. Variability in access to hospital palliative care in the United States. J Pall Med. 2008;11:1094–1102. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. [Accessed June 15, 2010];Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. (2). 2009 Available at http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org.

- 7.National Quality Forum. [Accessed June 15, 2010];A National Framework and Preferred Practices for Palliative and Hospice Care Quality: A Consensus Report. 2006 Available at http://www.qualityforum.org/Publications/2006/12/A_National_Framework_and_Preferred_Practices_for_Palliative_and_Hospice_Care_Quality.aspx.

- 8.Weissman DE, Meier DE. Operational features for hospital palliative care programs: Consensus recommendations. J Palliat Med. 2008;11:1189–1194. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2008.0149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Campbell ML, Frank RR. Experience with an end-of-life practice at a university hospital. Crit Care Med. 1997;25:197–202. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199701000-00034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carlson RW, Devich L, Frank RR. Development of a comprehensive support care team for the hopelessly ill on a university hospital medical service. JAMA. 1988;259:378–383. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell ML, Guzman JA. Impact of a pro-active approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical ICU. Chest. 2003;123:266–271. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Billings JA, Keeley A, Bauman J, et al. Merging cultures: Palliative care specialists in the medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(Suppl):S388–S393. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237346.11218.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Norton SA, Hogan LA, Holloway RG, et al. Proactive palliative care in the medical intensive care unit: Effects on length of stay for selected high-risk patients. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:1530–1535. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000266533.06543.0C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.O’Mahony S, McHenry J, Blank AE, et al. Preliminary report of the integration of a palliative care team into an intensive care unit. Palliat Med. 2010;24:154–165. doi: 10.1177/0269216309346540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1166–1172. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Buckley JD, Addrizzo-Harris DJ, Clay AS, et al. Recommendations of competencies in pulmonary and critical care medicine. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:290–295. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200904-0521ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke EB, Curtis JR, Luce JM, et al. Quality indicators for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2255–2262. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000084849.96385.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. [Accessed June 15, 2010];End of Life Nursing Education Consortium (ELNEC)—Critical Care train the trainer program. Available at http://www.aacn.nche.edu/ELNEC/CriticalCare.htm.

- 19. [Accessed June 15, 2010];Initiative for Pediatric Palliative Care Curriculum. Available at http://www.ippcweb.org/curriculum.asp.

- 20. [Accessed March 1, 2010];Critical Care Communication (C-3) Skills Training Program for Intensive Care Fellows. Available at http://www.upmc.edu/palliativecare/resources.htm.

- 21.Center to Advance Palliative Care. [Accessed June 15, 2010]; Available at http://www.capc.org/

- 22.Pronovost P, Needham D, Berenholtz S, et al. An intervention to decrease catheter-related bloodstream infections in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2006;355:2725–2732. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA, Barker LK, et al. Changing the culture around end-of-life care in the trauma intensive care unit. J Trauma. 2008;64:1587–1593. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e318174f112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Treece PD, Engelberg RA, Crowley L, et al. Evaluation of a standardized order form for the withdrawal of life support in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1141–1148. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000125509.34805.0c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nelson JE, Walker AS, Luhrs CA. Family meetings made simpler: A toolkit for the intensive care unit. J Crit Care. 2009;24:626.e7–e14. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.02.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gay E, Pronovost P, Bassett R, et al. The ICU family meeting: Making it happen. J Crit Care. 2009;24:629.e1–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med. 2000;109:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nelson JE, Mulkerin CM, Adams LL, et al. Improving comfort and communication in the ICU: A practical new tool for quality improvement and performance feedback. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:264–271. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.VHA Inc. Transformation of the ICU (TICU) Care and Communication bundle of ICU Palliative Care Quality Measures. National Quality Measures Clearinghouse of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality; [Accessed March 1, 2010]. Available at: http://www.qualitymeasures.org/summary/summary.aspx?doc_id=9943&string=palliative+AND+care. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mosenthal AC, Murphy PA. Interdisciplinary model for palliative care in the trauma and surgical intensive care unit: Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Demonstration Project for Improving Palliative Care in the Intensive Care Unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(Suppl):S399–S403. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237044.79166.E1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Needham DM. Translating evidence into practice: A model for large scale knowledge translation. BMJ. 2008;337:a1714. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Campbell ML, Guzman JA. A proactive approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical intensive care unit for patients with terminal dementia. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1839–1843. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000138560.56577.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pierucci RL, Kirby RS, Leuthner SR. End-of-life care for neonates and infants: The experience and effects of a palliative care consultation service. Pediatrics. 2001;108:653–660. doi: 10.1542/peds.108.3.653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Impact of a family information leaflet on effectiveness of information provided to family members of intensive care unit patients: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:438–442. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.200108-006oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Erdek MA, Pronovost PJ. Improving assessment and treatment of pain in the critically ill. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16:59–64. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chanques G, Jaber S, Barbotte E, et al. Impact of systematic evaluation of pain and agitation in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1691–1699. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000218416.62457.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Payen JF, Bosson JL, Chanques G, et al. Pain assessment is associated with decreased duration of mechanical ventilation in the intensive care unit: A post hoc analysis of the DOLOREA study. Anesthesiology. 2009;111:1308–1316. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181c0d4f0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: An epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gelinas C. Management of pain in cardiac surgery ICU patients: Have we improved over time? Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2007;23:298–303. doi: 10.1016/j.iccn.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nelson JE, Mercado AF, Camhi SL, et al. Communication about chronic critical illness. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2509–2515. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.22.2509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Azoulay E, Timsit JF, Sprung CL, et al. Prevalence and factors of intensive care unit conflicts: The Conflicus study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;180:853–860. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200810-1614OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, et al. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1722–1728. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174da72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Anderson WG, Arnold RM, Angus DC, et al. Posttraumatic stress and complicated grief in family members of patients in the intensive care unit. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1871–1876. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0770-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Embriaco N, Azoulay E, Barrau K, et al. High level of burnout in intensivists: Prevalence and associated factors. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:686–692. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200608-1184OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Poncet MC, Toullic P, Papazian L, et al. Burnout syndrome in critical care nursing staff. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2007;175:698–704. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200606-806OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ray D, Fuhrman C, Stern G, et al. Integrating palliative medicine and critical care in a community hospital. Crit Care Med. 2006;34(Suppl):S394–S398. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237046.62046.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Curtis JR, Treece PD, Nielsen EL, et al. Integrating palliative and critical care: Evaluation of a quality-improvement intervention. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2008;178:269–275. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200802-272OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]