Abstract

Objective

Although the majority of hospital deaths occur in the intensive care unit and virtually all critically ill patients and their families have palliative needs, we know little about how patients and families, the most important “stakeholders,” define high-quality intensive care unit palliative care. We conducted this study to obtain their views on important domains of this care.

Design

Qualitative study using focus groups facilitated by a single physician.

Setting

A 20-bed general intensive care unit in a 382-bed community hospital in Oklahoma; 24-bed medical–surgical intensive care unit in a 377-bed tertiary, university hospital in urban California; and eight-bed medical intensive care unit in a 311-bed Veterans’ Affairs hospital in a northeastern city.

Patients

Randomly-selected patients with intensive care unit length of stay ≥5 days in 2007 to 2008 who survived the intensive care unit, families of survivors, and families of patients who died in the intensive care unit.

Interventions

None.

Measurements and Main Results

Focus group facilitator used open-ended questions and scripted probes from a written guide. Three investigators independently coded meeting transcripts, achieving consensus on themes. From 48 subjects (15 patients, 33 family members) in nine focus groups across three sites, a shared definition of high-quality intensive care unit palliative care emerged: timely, clear, and compassionate communication by clinicians; clinical decision-making focused on patients’ preferences, goals, and values; patient care maintaining comfort, dignity, and personhood; and family care with open access and proximity to patients, interdisciplinary support in the intensive care unit, and bereavement care for families of patients who died. Participants also endorsed specific processes to operationalize the care they considered important.

Conclusions

Efforts to improve intensive care unit palliative care quality should focus on domains and processes that are most valued by critically ill patients and their families, among whom we found broad agreement in a diverse sample. Measures of quality and effective interventions exist to improve care in domains that are important to intensive care unit patients and families.

Keywords: intensive care, critical care, palliative care, quality assessment, health care, quality indicators, qualitative research

Improving the quality of palliative care is identified by those who receive, deliver, pay for, and evaluate health care in the US as a top health priority (1, 2). Although the majority of hospital deaths occur in the intensive care unit (ICU) (3) and virtually all critically ill patients and their families have palliative needs (4, 5), we know little about how patients and families, the most important “stakeholders,” perceive or define high-quality palliative care in the ICU. A consortium of organizations led by professionals, the National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care, identified eight “domains of quality palliative care” supporting guidelines for practice across a spectrum of clinical settings (6). The Critical Care Peer Workgroup of Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life care addressed the ICU specifically, deriving seven domains of palliative care quality through professional consensus (7).

In this qualitative study, we asked patients and families who experienced ICU care for at least 5 days to define high-quality palliative care. We used focus groups with a diverse sample across three institutions for direct, open-ended exploration of participants’ views. This report presents our findings and discusses implications for evaluating and improving the quality of palliative care in critical care settings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

In 2007 to 2008, we convened focus groups of randomly selected patients who survived the ICU, families of survivors, and families of patients who died in ICU, at each of three sites: 20-bed general ICU in a 382-bed community hospital in Oklahoma; 24-bed medical–surgical ICU in a 377-bed tertiary, university hospital in urban California; and eight-bed medical ICU in 311-bed Veterans’ Affairs hospital in northeastern city. We used hospital databases to identify all ICU patients 21 yrs or older with ≥5 consecutive ICU days between January 1, 2006 and June 1, 2007. We created three randomized lists for recruitment in the specified categories (patients, families of survivors, families of non-survivors).

We excluded subjects with more than an hour’s drive to the hospital and families of patients who died after ICU discharge. By telephone, a research nurse determined subjects’ English proficiency and physical and cognitive ability to participate. Family members were included if they visited the patient in the ICU. Eligible subjects were invited to a focus group discussing quality of ICU care. We targeted a group size of approximately 6. Participants received a $50 stipend. The research received Institutional Review Board approval at all sites and all participants provided written informed consent.

Meetings

One experienced facilitator (JN) conducted all focus groups across all sites using a written guide containing open-ended questions followed by scripted probes (Appendix). Participants were asked to consider the quality of ICU care other than medical or surgical treatments to stabilize the patient, reverse illness, restore physical health, prolong life, or prevent complications. The facilitator initially asked participants to define “high-quality care” by the ICU and to identify care components with the greatest impact and those most valued during their ICU experience. The facilitator did not initiate use of the term “palliative care” in the focus group meetings because this term might not be familiar to participants who were not healthcare professionals, and because use of this term might limit a full and open discussion of components of care that participants considered important. Probe questions were deferred until after all participants had a full opportunity to respond to open-ended questions and to comments by other participants. Probes addressed palliative care attributes that were identified as important by patients and families in previous research outside the ICU setting (8–10). Probes also addressed participants’ views of ICU palliative care domains established through professional consensus (6, 7, 11, 12). Table 1 summarizes those domains. The facilitator asked participants to discuss “actions by ICU clinicians that are indicators or examples of high-quality ICU care.” Probes addressed specific care processes endorsed by critical care professionals (7, 11–13). The initial written guide was refined as successive focus groups were conducted to include items that participants identified as important. The same overall approach was used with all groups. At each meeting, attendance by another health care professional (nurse or social worker) helped to ensure that facilitation adhered to the open-ended protocol and avoided bias. Meetings were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Demographic information about participants was obtained with a brief questionnaire on-site before the meeting.

Table 1.

Domains of palliative care from (selected) prior literature

| Study/Method | Subjects | Domains |

| Singer et al (10) | Outpatients on dialysis or with human immunodeficiency virus | Receiving adequate pain and symptom management |

| Qualitative: In-person, open-ended interviews | Residents of long term care facility | Avoiding inappropriate prolongation of dying |

| Achieving a sense of control | ||

| Relieving burden | ||

| Strengthening relationships with loved ones | ||

| Steinhauser et al (9) | Outpatients with cancer or human immunodeficiency virus | Pain and symptom management |

| Qualitative: Focus groups and in-person interviews | Bereaved family members | Clear decision making |

| Healthcare professionals and volunteers | Preparation for death | |

| Completion | ||

| Contributing to others | ||

| Affirmation of the whole person | ||

| Teno et al (8) | Bereaved family members | Provides physical comfort to patients |

| Qualitative: Focus groups | Helps patients take control over decisions about medical care and daily routines | |

| Relieves family burden of being present at all times to advocate for the patient | ||

| Educates family to care for their loved ones at home | ||

| Provides family with emotional support before and after the patient’s death | ||

| Heyland et al (16) | Hospital in-patients with “serious illness” and their families (50% risk of death within 6 months) | Highest ratings among 28 items: |

| Quantitative: Questionnaire-based interview | Trust and confidence in physicians | |

| Avoidance of unwanted life support | ||

| Communication with physician | ||

| Life completion including life review, resolving conflicts, and saying goodbye | ||

| Symptom relief | ||

| National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care (6) | Professional consensus | Structure and processes of care |

| Consortium of U.S. palliative care organizations | Physical aspects of care | |

| Psychological and psychiatric aspects of care | ||

| Social aspects of care | ||

| Spiritual, religious, and existential aspects of care | ||

| Cultural aspects of care | ||

| Care of the imminently dying patient | ||

| Ethical and legal aspects of care | ||

| Critical Care Peer Workgroup - Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Promoting Excellence in End-of-Life Care Project (7) |

Professional consensus | Symptom management and comfort care |

| Patient and family-centered decision making | ||

| Communication within the team and with patients and families | ||

| Emotional and practical support for patients and families | ||

| Spiritual support for patients and families | ||

| Continuity of care | ||

| Emotional and organizational support for intensive care unit clinicians |

Analysis

Three investigators independently reviewed each transcript, coding all passages of speech (entire segment before change of speaker; segment in which initial speaker continued with only a brief interruption; segment in which several speakers exchanged a series of comments on same topic). We used the facilitator’s guide with palliative care domains and processes as a preliminary coding framework. We revised domains to reflect the focus group discussions. After independent coding of several transcripts, reviewers met to compare initial results, achieving consensus on interpretation of each passage. We used ATLAS.ti software to sort passages according to codes and examine relationships among codes and coded passages to elaborate our coding framework. First independently and then together, reviewers continued this process, using the newest version of the framework to code additional transcripts. For inclusion as a key domain of palliative care quality, we required that the domain arise spontaneously in discussion by participants; that the spontaneous discussion reflect agreement among participants on the importance of this domain; and that no participant expressed disagreement about the domain’s importance. We continued focus groups and transcript analysis until no new codes emerged and the framework stabilized. Our final framework thus represented an inductive product, grounded in data collected over multiple meetings with ICU patients and families across all sites. Using the ATLAS.ti searching function with this framework, we selected representative quotes for presentation here. We removed some repeated words and grammatical errors but made no substantive changes in quotation content.

RESULTS

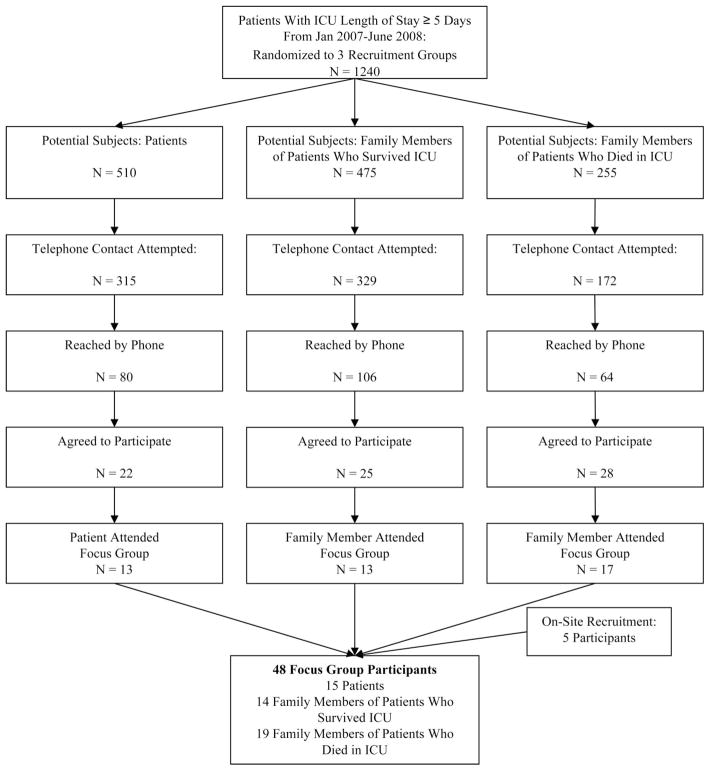

Recruitment is summarized in Figure 1. In total, nine focus groups (three per site) included 48 participants (15 patients, and 33 family members of patients who survived [n = 14] or who died [n = 19]); the average (SD) number of participants per group was 5.3 (1.5). These subjects included five individuals who escorted relatives to the meetings, were themselves eligible for the group, and expressed interest in participating; they provided research consent and enrolled on site. Family member focus groups included either bereaved relatives of patients who died in ICU or families of survivors, but not both in the same meeting; patients participated in their own groups, except for one who mistakenly arrived for a family focus group, which she was allowed to join. To resolve a scheduling conflict, the facilitator used the focus group guide to conduct a single structured interview with one family member. Meetings lasted 123 ± 29.7 minutes on average.

Figure 1.

Recruitment to focus groups of randomly-selected patients, families of survivors, and families of patients who died in the intensive care unit (ICU).

Table 2 shows participant characteristics. There were no significant differences in age, gender, or ICU length of stay between patients who participated or whose family members participated vs. those who declined to participate or whose families declined.

Table 2.

Patient and family participants in focus groups (n = 48)a

| Focus Group Sites: OK, CA, NY | Patients n = 15 |

Family Members n = 33 |

Total n = 48 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, yrs, mean (range) | 58.5 (34–87) | 60.4 (26–86) | 59.7 (26–87) |

| Female, n (%) | 7 (46.7) | 26 (78.8) | 32 (66.7) |

| Race/ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 11 (73.3) | 20 (60.6) | 31 (64.6) |

| Black | 1 (6.7) | 7 (21.9) | 8 (16.7) |

| Hispanic | 1 (6.7) | 4 (12.5) | 5 (10.4) |

| Other | 2 (13.3) | 2 (6.3) | 4 (8.3) |

| Religion, n (%) | |||

| Catholic | 4 (26.7) | 8 (25.8) | 12 (26.1) |

| Protestant | 3 (20.0) | 14 (45.2) | 17 (36.9) |

| Jewish | 2 (13.3) | 2 (6.5) | 4 (8.7) |

| Other | 6 (40.0) | 7 (22.6) | 13 (28.3) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Married | 9 (60.0) | 15 (48.4) | 24 (52.2) |

| Divorced/separated | 2 (13.3) | 3 (9.7) | 5 (10.9) |

| Widowed | 1 (6.7) | 11 (33.3) | 11 (23.9) |

| Never married | 3 (20.0) | 3 (9.7) | 6 (13.0) |

| Patient length of ICU stay, median (IQR) | 8.0 (7.0, 10.3) | 9.8 (7.0, 17.0) | 9.0 (7.0, 13.4) |

| Family relationship to patient, n (%) | |||

| Spouse | 14 (43.8) | 14 (43.8) | |

| Adult child | 7 (21.9) | 7 (21.9) | |

| Other family | 11 (34.4) | 11 (34.4) | |

| Number of visits by family subject to ICU, n (%)b | |||

| Once | 1 (3.2) | 1 (3.2) | |

| 2–5 times | 7 (22.6) | 7 (22.6) | |

| >5 times | 23 (74.2) | 23 (74.2) | |

| Education, n (%) | |||

| Some high school | 0 | 2 (6.5) | 2 (4.3) |

| High school graduate | 2 (13.3) | 5 (16.1) | 7 (15.2) |

| Some college | 9 (60.0) | 7 (22.6) | 16 (34.8) |

| College graduate | 4 (26.7) | 17 (54.8) | 21 (45.7) |

| Employment, n (%) | |||

| Full-time | 2 (13.3) | 6 (19.4) | 8 (17.4) |

| Part-time | 0 | 4 (12.9) | 4 (8.7) |

| Retired | 6 (40.0) | 17 (54.8) | 23 (50.0) |

| Unemployed | 7 (46.7) | 4 (12.9) | 11 (23.9) |

| Income, n (%) | |||

| <$25,000 | 4 (26.7) | 6 (20.0) | 10 (22.2) |

| $25,000–$50,000 | 3 (20.0) | 11 (36.7) | 14 (31.1) |

| >$50,000 | 4 (26.7) | 5 (16.7) | 9 (20.0) |

| Rather not say | 4 (26.7) | 8 (26.7) | 12 (26.7) |

Not all variables in the table add to 48 because some data were missing for one family subject;

at least one visit by family was an entry criterion for the study.

Patients and families in our focus groups identified four aspects of ICU palliative care that were most important to them: communication by clinicians about the patient’s condition, treatment, and prognosis; patient-focused medical decision-making; clinical care of the patient to maintain comfort, dignity, personhood, and privacy; and care of the family. Table 3 presents the specific processes and components of care representing these domains, which are discussed more fully.

Table 3.

Definition of high-quality intensive care unit palliative care by patients and families

| Important Domains of High-Quality ICU Palliative Care as Identified by Patients and Families |

|---|

| Communication by clinicians: |

| Timely, ongoing, clear, complete, compassionate |

| Addressing condition, prognosis, and treatment |

| Patient-focused medical decision-making: |

| Aligned with patient values, care goals, treatment preferences |

| Clinical care of the patient: Maintaining comfort, dignity, personhood, privacy |

| Responsive and sensitive to patient’s needs |

| Maintaining physical comfort |

| Respecting dignity |

| Treating the patient as a person—somebody’s loved one |

| Protecting privacy |

| Care of the family: Providing access, proximity, and support |

| Allowing liberal, flexible visiting |

| Valuing family input about patient needs and care |

| Offering practical, emotional, spiritual support to family |

| Offering bereavement support |

| Important Care Processes and Structural Aspects of High-Quality ICU Palliative Care as Identified by Patients and Families |

| Regular family meetings with attending physician and nurse |

| Flexible, liberal, policy on visiting |

| Early identification of surrogate decision-maker/advance directive/resuscitation status |

| Frequent assessment of pain and titration of analgesia to maximize comfort and achieve desired level of consciousness |

| Offer of pastoral care with sensitivity and without mandate |

| Offer of practical and emotional (social work) support |

| Printed information about ICU for families |

| Offer of bereavement support to families of patients dying in the ICU |

| Waiting room affording comfort and privacy to families |

Communication

In all focus groups, communication was the dominant theme of the discussion by patients, families of ICU survivors, and bereaved families. As a patient’s widow said, with all group members nodding vigorously, “Nothing, nothing was important to me as much as just being able to talk to the doctor and to get the information there.” The wife of another patient, who reported receiving frequent and effective communication in meetings that included the ICU physician, bedside nurse, and hospital chaplain, agreed: “It’s very important that you know every day what is happening, because every day in an ICU is different.” According to one patient, the top priority was clinician “communication, with compassion … because, being in the dark is like being in oil.”

Participants expressed confusion and frustration with clinicians’ use of medical terminology. “I do not have a medical background,” said a family member, “so … I would be saying, please, tell me in English.” Another observed, ICU clinicians “are used to abbreviating long words with letters. So you get alphabet soup and go, what’s that?” Patients and families particularly valued clarity in communication about burdens and benefits of critical care treatments: “Put this in layman’s terms for my family to understand. Why are you doing these tests and things that are painful and intrusive? Is there really reason enough to do it?” Clinicians in one ICU were praised for “using terms that a person that’s not a doctor could understand … You did not need to go get a dictionary to look it up … they explained themselves well.”

Another source of confusion was information from multiple clinicians that seemed inconsistent to patients and families. Many participants had interacted with caregivers from various specialties and disciplines. Some regretted what they perceived as an absence of coordination and leadership by a single physician: “A lot of times, we did not know who was in charge … Do they ever sit down and have somebody leading the discussion that’s the patient’s main doctor? You had all kinds of specialists.” One family member commented, “if you gotta talk to two or three specialists, they come in with conflicting information.” Another, who had a “very positive experience,” attributed consistent communication with the family to better communication within the ICU team: “So many different teams of doctors and nurses were involved … but those people were all communicating … were all on the same page.” A patient emphasized, “the communication between doctors and nurses, that’s paramount … You want to make sure that the chain of communication between doctors, nurses, and patients is not broken, because if it is broken, the patient is gonna get lost.”

Participants discussed implications of inadequate communication between ICU physicians and families. A patient expressed concern about consequences for medical decision-making by his wife:

“The lack of communication was so severe that my wife could not even make informed decisions as to my care. She could not find out enough … Nobody told her anything, and this went on for eight days. Nothing. The doctors wouldn’t come by. If they did, they wouldn’t tell her anything. She had no idea what was going on.”

Another patient spoke about emotional consequences for his family: “The family’s stress level is so high to begin with, and this just adds more stress, not knowing what my condition is.” For the brother of a patient who died, the family’s failure to appreciate the imminent risk of a poor outcome, which he attributed to the physician’s delayed delivery of prognostic information, impeded psychological preparation for the death and foreclosed an opportunity to say goodbye:

“Right up until the last time that the doctor called me, I always thought my brother was gonna get better and come home. It would have been advantageous for me and my family if, at a point, of the better than 2 weeks that he was in ICU, we could have had some kind of counseling on end of life issues. Because I never thought of it, and then the doctor called us … and said, your brother is not doing well … he is not responding to anything. This was the first time that I had to come face-to-face with this possibility, that this was the last time I was going to see my brother. And, I believe I would have benefited greatly, if previous to this, I had been told by the doctor that this is the possibility, you need to start thinking about this. I just wasn’t ready for it … We got a call at 5 AM and my brother was gone. And I never had the chance, you know. Looking back you always see what ifs, but I’ve, I’ve agonized over this … Every time they called, it was surgery to fix something. When they’re doing surgery to fix something, you assume it’s going to be fixed … you get well and you go home, so consequently, every time, I was called up for surgery, to sign the papers … it was, my brother is gonna be fixed … I wasn’t aware until that last day … [Discussing the prognosis sooner] might have helped me prepare mentally.”

Participants understood that discussion of prognosis was difficult for clinicians, requiring sensitivity and adaptation to needs of individual patients and families. As one family member noted, “It depends on the type of individual you are and how you can handle hearing what they have to tell you.” There was broad agreement about the value of open and complete communication, even if the physician was unsure or pessimistic about the patient’s prospects: “We all want to know what’s going on, how bad are they, how quickly are they going to get better, or are they going to get worse?” A surviving patient explained:

“Suppose your mate or whoever is close to you expects you to make it … Now if you do not make it, this is going to be a surprise and everyone would be angry with the doctor … If the doctor is reluctant to talk about this, he is not being honest with you or himself … There might be some complications, you can never tell. . . . Be honest, so, if you do not come out alive, [the family members] are not surprised, they expected that, they are going to be disappointed, but they realized that you might not make it.”

Describing “a great physician,” one who “defines the good quality of care,” a family member captured a central group theme: “She’s going to tell you, she’s not going to give you a line, but she’s still sensitive. That’s the key.”

Participants placed high value on the ICU family meeting, which they believed improved communication and should be held proactively and frequently. A patient observed: “Knowledge is power, and if my family is informed, then they could have comfort knowing what my status is and how I am progressing or not progressing, day to day, what to expect in the near future.” Asked for his view of regular meetings with the doctor in charge and another ICU team member, a patient’s brother stated “that would be the very best thing that I can say all day today. If they would just say, okay, we’re real busy, but we can be there at 10:20, then the family member can make it there. We’ll go along with their schedule. We know they’re busy, but man, would that be helpful.” Many participants suggested that nurses join meetings; one family member said “that would be perfect,” while the whole group nodded approvingly. Another expressed this view of the importance of coherent communication from the ICU team, suggesting a regularly scheduled and interdisciplinary process:

“ICU has rounds at a certain time in the morning. And after that time, when everybody that works there has met and talked, that would be a good time to arrange a family meeting, so we could find out what are they all thinking, what are their plans, just for today, to know what’s going on, instead of day after day, not being sure, not being able to get a hold of the doctor.”

Patient-Focused Decision-Making

Participants saw decision-making for ICU patients as complex, encompassing multiple components. The task for surrogate decision-makers seemed especially challenging, and some families looked for clearer recommendations from physicians:

“The doctor would tell you, you can do this or this or this or this or this. And, it’s a medical decision, but it’s also an emotional decision and a financial decision, and … I did not know what was best. The doctor would say, ‘well, I cannot advise you, but these are your options.’ But if I asked, ‘what would you do?’, then he could answer that question. And then I had more information to make my decision on, whereas he was, ‘you’ve got these choices.’”

Patients and families agreed that the ICU should attempt early to elicit the patient’s values and treatment preferences. One patient thought it was crucial for the ICU to “know what I prefer” so that her family “would never feel guilty about having to make a decision.” Another, whose preeminent concern was to avoid “being a burden to my family,” stressed that she “would want the ICU to know that … at the beginning, absolutely,” and when asked if investigation of patient preferences should occur on admission to ICU, replied, “they should know before you even get into ICU.” For patients who had previously expressed preferences in an advance directive, there was agreement among participants that “the ICU needs to know immediately” before major decisions were actually at hand, if possible, “before something tragic happens.” “What’s the point of making one out if the information’s not passed on?” in a timely way, a family member asked, rhetorically. Participants reported, with regret, that investigation of patient preferences was deferred until late in the ICU stay. The brother of a patient who died stated:

“Nobody took me off to one side, until that very last day, when the two doctors, and I guess the head nurse, went down into the room and discussed, okay, do you want us to pull the plug, or, and we discussed at that moment, that [my brother] and I, both of us, had talked it over with each other, years before, when we were discussing my mother’s passing, that that’s the way we wanted it, if I can get better and have a normal life, then fix me, if not, do not extend it artificially.”

Delay deepened the distress of the family of another patient, whose advance directive not to initiate mechanical ventilation or attempt resuscitation was unavailable when he began to rapidly deteriorate:

“He had esophageal cancer, so we know it’s got a very, very low survival rate, so, as soon as he was diagnosed, he got [an advance directive] in place … One of the nurses came out and said, ‘it’s getting to the time where we need to decide’ … and I said, we’re not going to prolong this, and she said, ‘do you have paperwork?’ I said, yes, I’ve got paperwork, it’s on file here. She called downstairs to medical records, they could not find it, and so I am just panicking, because I’m thinking he’s going to code, and they’re going to try, and he only weighs 80 pounds, so I sent my husband immediately to get it, and we live in another city. An hour and a half of anguish, and it wasn’t necessary.”

Clinical Care of the Patient: Comfort, Dignity, Personhood

A definition of high-quality clinical care of the patient emerged as encompassing two key components: assurance of comfort and attention to dignity and personhood.

Comfort

Participants discussed the importance of assuring that patients were not in pain. Patients recalled pain and stressed the need for timely and effective analgesia. A man who received surgical ICU care stated:

“I came to know what pain is. Once that pain came, man, I knew it was pain. Give me something. And the one thing I used to hate, when it’s coming on and you’re pressing the button, and they do not come, and you’re in a lot of pain. Being Latino, you know, in the culture, is like, you gotta be a man … you do not take nothing. Hey, that went out the window, right away, I said, man, I’m gonna confess, I got some pain here … I do not like pain. I have come to know it.”

A medical patient stressed the importance of frequent assessment for pain:

“How can they expect the doctors and the nurses to know what your pain is? They do not know, unless you tell them … and it will change … Every time they come in the room they should ask, ‘How is your pain today, how is your pain tonight, what can we do to help you with it?’.”

Family members also prioritized the comfort of patients. “On the pain issue,” said the mother of an ICU patient who recovered, “I think it’s inhumane to let a patient suffer, even if they are in a coma, from pain. Because my daughter says she cannot remember anything from her ICU experience except the pain.” Families could not feel comfortable without assurance of the patient’s comfort. As an ICU patient’s widow reported, “Because of a lot of the cords and everything that was going in him … I told [the doctor] I need to know that [my husband] is not hurting and cannot communicate this to me or to you.” Patients and families viewed comfort as an essential component of restorative ICU care. A patient commented, “I would have liked to have told them, gee, I really, really am hurting, on a scale of one to ten, can you do something about it? … [Relief of pain] is very important to your recovery. You do not feel good, you just do not care.” The wife of another patient agreed, “I think it’s very important that they take care of the patient’s pain level. I do not think you can heal if you’re in a great deal of pain constantly.”

Dignity and Personhood

There was also broad agreement about the importance of patient dignity. Many family members were distressed to see patients exposed in open or glass-walled ICU cubicles, without efforts to shield private areas of the body from public view. A young patient defined a key attribute of quality ICU care through this description of her primary nurse:

“What really made it different was she treated me with respect and dignity, and the dignity was what made it above and beyond. There were certain things that I could not do, I was not able to physically do, that were humiliating, that she had to do for me, and it was very, very, not pretty, it was very gross. But she treated me with respect and dignity and I thanked her profusely. She said it was just my job, and I know, but, thank you. You really make the difference … And that really contributed to my healing, and getting better, and, she did a great job.”

In every group, multiple participants stressed attention to personhood, defined in the literature as the belief that “each person is unique, has inherent value, and is worthy of respect and honor regardless of disease or disability” (14). Patients and families repeatedly noted the importance of clinicians “treating the patient as a person.” From a man whose mother died in the ICU:

“My mother had a team of doctors … Some were good, and I thought some had a blank face, looking at my mother as just a number, number 35. So what I did, I said, my mother is not just an old lady, my mother had a life, of course now she’s hooked up to a million cables. I brought in pictures of my mother when she was born, and when she got married to my father in 1936, and how she looked later on. And they saw her differently. It’s not just a piece of meat that is sitting in that hospital bed. It’s a life. That is 100% important.”

Others saw it as a measure of excellence for ICU clinicians to treat patients with the same care and concern they would give to a member of their own family, or at least to approach the patient as another’s loved one—someone’s mother, father, sibling, or child. One participant, however, offered the insight that clinicians might remain more impersonal, “distant,” and detached “as a defense mechanism.” As this family member observed, “Their job is very hard … So that is the way of saying, I am not going to get involved. I am not going to feel it. Because, you know, they see people die every day. And if they get involved emotionally, they could not function.” Another family member suggested this approach for clinicians, “That was my mother. They need to realize that that’s somebody’s loved one in there … It’s not like they need to have an emotional bond with each and every one of our relatives, but they need to have some compassion for these people.”

Care of the Family: Access and Proximity, and Support Including Bereavement Care

Support for families was identified by patients and family members as an important part of ICU care. As a woman whose father died in the ICU commented:

“I think that while their focus is medical and saving lives and, you know, the science, I think also, along with that comes the responsibility of some kind of support to a relative or a family, that patient’s loved one or caregiver. Yeah, and they actually did that, and that is part of high-quality care.”

A patient suggested that he and others were more concerned about their families than themselves: “The mind of the patient is not on himself only; his mind is also toward the family that is beside him, that is caring for him. Most times, most of the patients do not care much about themselves. But they care for the family that has been giving them support.” Focus group participants identified attention to families’ emotional, practical, and spiritual needs as high-quality ICU care.

Access and Proximity

Both patients and families placed high value on family access and proximity to the patient. Participants recognized that visitation might be appropriately limited for short periods to facilitate changes of shift or reporting, address emergency issues, or encourage family members to rest. However, support was overwhelming for maximal openness and flexibility for family visiting. Patients emphasized their awareness of family presence and the comfort and strength they derived from it. Whereas they might appear unconscious, said one patient, “we do hear. I knew each and every person that visited me, and talked to me, and touched me. I do not know why people say, go away, they cannot hear you; they do not have any brain activity. Because, yes we do. We do hear.” This patient spoke of her need for, and benefit from, the presence of family at her bedside:

“My friends and, more importantly, my family played a very, very big part in my, in my comfort level, and my emotional healing. And for me, the emotional healing is high, right there with physical healing. It’s all one. I would stare at the clock, and wait for visiting hours to come, and that was just very, very crucial for my personal healing, to get better and get out of here.”

Families offered many reasons why they should be able to visit freely, including their role in supporting patients emotionally, serving as advocates, protecting patients from potential medical errors, recognizing and interpreting signs that might otherwise be missed or misunderstood, conveying the patient’s personal qualities and family context, assisting in care within their capabilities, and participating in decision-making. As described by the brother of an ICU patient who survived, “I probably made a nuisance of myself, but I really feel that my sister got much better care because I was there every day. I was a decision-maker, and I was a prodder, and I was a nagger, and I was an everything else.” Families also saw their presence as essential for communication with physicians, whose visits were unpredictable, as well as for addressing their own emotional distress, which they felt was intensified by restrictions on visiting.

Support From Multiple Disciplines

Families valued contributions not only of physicians and nurses but of other disciplines providing support in the ICU. Participants across a spectrum of religions and cultures suggested that pastoral care should be available for patients or families who want it. As stated by the sister of a patient who recovered after a prolonged critical illness, “The power of prayer cannot be outdone, especially in times of crisis, that is when people are looking for some place to go, for help. . . . Having someone that is going to come by and offer you prayers, it should not be forced upon anybody but it should be looked upon as a part of treatment that can help people.” Patients and families also noted the wide-ranging help they received from social workers. A family member summarized social workers’ role this way:

“If anybody has the story down and the plot and how it is going to turn out, the social worker does. They know what they need to bring to the table and what you are going to need help with … especially when you have a family member that is critically ill … They say the right things, know what to do … It should be an integral part of the care.”

Bereavement Care

Families of patients who died in the ICU stressed the importance of bereavement care, although few reported receiving this care. Those who experienced clinicians as supportive during the ICU stay nonetheless perceived an abrupt and distressing shift at the time of death. A patient’s daughter commented:

“I think that I did get very good attention and my father had the best of care, but … they just came and closed his eyes, started doing whatever they do when somebody dies, and basically just said to move. And, I just left. I did not know what else to do. . . . I would’ve liked a piece of follow-up, somehow. A call: ‘Ms.___, I know your father just recently died, how are you doing? Did you know there’s a group? Would you be interested in talking to someone? … It’s important for people who have recently lost their loved ones,’ or something like that.”

A man who had authorized withdrawal of mechanical ventilation from his dying mother described the challenge of coping without bereavement support from the ICU or hospital:

“At 8:00 PM, I went out there and felt like I was going into a war zone. I was put out like, out on the street. No one told me anything. They knew several days beforehand that I had arranged the date [for ventilator withdrawal], but nobody approached me … Nothing was addressed at all … Nobody asked, ‘Are you able to take care of yourself; are you able to find a place to go to, as far as for grief, for death of your mother?’ Where do you go, what do you do? … Prepare one for it a little bit. Not to walk out into the cold night.”

For a woman whose father died in the ICU, unmet need for bereavement care had long-lasting consequences:

“After he died, they just came in there and pronounced him dead, and started covering him up and moving him, and pulling out all these things. And, I thought, do they need the room right now? They do not give me a minute to just kind of get up and grab my stuff and get out? So, I just left. I would have appreciated some follow-up or grief support or social work or anything. Because I did not cry over my father. . . . I did not cry at all, until 2 months ago, I finally had myself a good little fit. I did not know that I was so messed up. I wished that I had spoken with someone. Or someone had reached out to me. In some way.”

DISCUSSION

To our knowledge, this is the first direct investigation of the perspectives of both patients and families, as described in their own words, on domains of palliative care quality in the ICU setting. Our cohort included 48 participants in nine focus groups in three locations across the country, following their exposure to different types of ICUs, hospitals, and local environments. The cohort comprised participants of different ethnic and religious backgrounds. Despite this diversity, and the open-ended focus group discussions, common themes emerged clearly and consistently. Participants in this study included four main domains in their definition of high-quality ICU palliative care: timely, clear, and compassionate communication by clinicians; clinical decision-making focused on patients’ preferences, goals, and values; patient care maintaining comfort, dignity, and personhood; open access and proximity of families to patients; and interdisciplinary support of families during the critical illness and, for families of patients who died in ICU, in the bereavement period (Table 3). They also endorsed specific processes to operationalize the care they considered important (Table 3).

Domains and processes of care defined in these focus group discussions are similar in important respects to those identified by professionals in critical care and other fields (Table 1) (6, 7, 15). In previous studies, patients or families in other clinical settings have also expressed similar views (Table 1) (8–10, 16). However, the definition of high-quality care provided by our focus group participants is significant because it comes directly from ICU patients and families, who are the focus of efforts to improve the quality of palliative care in the critical care setting and ultimately the “gold standard” for measuring our success. Although some past research suggests that ethnicity or other characteristics may influence certain attitudes about end-of-life care, diverse participants in our study, who had actually experienced ICU treatment over a prolonged period, expressed broad agreement about important aspects of palliative care in this setting.

Across all sites and focus groups that were part of this study, effective clinician communication received particular emphasis from participants. Such communication is known to promote more efficient utilization of critical care resources by helping patients and families establish appropriate goals of care and avoid prolonged use of non-beneficial treatments (17–19). Communication is also associated with favorable patient-focused and family-focused outcomes, including satisfaction with care, psychological well-being, and consensus related to decision-making (19–21). In interviews by Kirchhoff (22) of eight family members about the death of a loved one, subjects spoke of inadequate communication by clinicians as contributing to their sense of the ICU as a “vortex” of difficult experiences; those receiving more information described the overall outcome favorably. Respondents to Heyland’s questionnaire (21) emphasized adequate information as a key determinant of ICU family satisfaction. In our study, ICU patients and families illuminated the importance of timely, clear, and compassionate communication from the care team. They were clear that communication with the doctor and other ICU team members was what they waited for every day in the ICU. They wanted a mutual exchange of information to arrive at a care plan informed by the patient’s prognosis, preferences, and values. Taking part in a meeting with the ICU team helped families shoulder the responsibilities of surrogate decision-making, which often engendered confusion and guilt.

Effective, feasible, and resource-efficient interventions exist to improve ICU care in the ways that patients and families have identified as important. Simple tools have long been available to assess pain in patients who can self-report, and newer methods can be used for assessment of pain in those who cannot (23, 24). Use of these tools with a practical, protocol-driven, interdisciplinary approach to ICU care can reduce the incidence and severity of pain and increase therapeutic changes that achieve closer titration of analgesia and reduction of mechanical ventilation (25, 26). Evidence and consensus guidelines on analgesia and sedation can serve as a foundation for systematic ICU initiatives to promote patient comfort (27–29).

Leaflets and brochures can meet specific informational needs of ICU families. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated that appropriate printed materials improve comprehension of critical illness and contribute to longer-term psychological adjustment by ICU families (20, 30). Although printed information is not a substitute for direct clinician counseling, it augments it at a low-cost and helps families make informed decisions and cope with their own stresses in the ICU. Recent research outlines practical implementation strategies to improve timeliness, reliability, and quality of implementation of family meetings (31, 32). Evidence-based templates and tools are available to facilitate these efforts (33).

Patients and families in our study gave voice to a paradigm of person-centered care that stresses the uniqueness and worth of each individual and the necessity to respect distinct histories, values, and preferences (14). One strategy is a simple and inexpensive “Get to Know Me Poster” at the ICU bedside (34), that describes the patient as a person. Preservation of patients’ privacy during personal care requires little more than routine, systematic vigilance by professional care-givers. A survey of families of patients who died in ICU elicited strongly positive reactions to bereavement interventions including support group information, mailing a sympathy card several weeks after the death, and a follow-up phone call and letter to the family (35). Such interventions require few resources while helping to address needs strongly expressed by participants in our groups. Proactive bereavement care attenuates longer-term anxiety, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder, and complicated grief for families (20, 36–38).

There is increasing support in the critical care community for greater flexibility and openness for family visiting (13, 15, 39, 40). A recent randomized controlled trial showed an association between liberal family visiting and fewer cardiocirculatory complications in ICU patients (41). Some healthcare professionals have taken a strong stand in favor of unrestricted visiting by families (42, 43). A substantial minority of others endorses continued restrictions in the belief that these are necessary for proper patient care and staff efficiency (42). In our focus groups, it was not only families who spoke of the importance of their access and proximity to patients but also patients. Family members in this study, as in previous research (44), described many useful roles they could perform if permitted to be present, and explained how essential they considered this presence both for the patients’ and their own well-being. We also heard clearly from patients for whom closeness of their loved ones was crucial for relief and recovery.

The views and experiences of our focus group participants add personal, vivid, first-hand descriptions of the need for effective strategies by critical care clinicians to address palliative needs of patients and families. They also contribute to a framework for evaluating the quality of ICU palliative care. ICU patients and families told us what they think are key attributes of palliative care quality and what clinician behaviors and care processes are indicators of the quality of ICU palliative care. We can use these empirical data, along with perspectives of professionals (6, 7) and other sources, to assess validity of quality measures already developed and to guide further efforts to evaluate and improve palliative care. For the ICU specifically, a set of nine process measures of palliative care quality has been posted on the National Quality Measures Clearinghouse web site maintained by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (1, 12). The findings reported here suggest that those process measures address attributes of palliative care that are important to patients and families. Our focus group participants also valued maximum family access to the patient (13), bereavement support for families of patients dying in the ICU, and attention to dignity and personhood.

Attributes of quality can be operationalized as either care process measures or structural measures (45–47). Well-specified measures that are both scientifically sound and feasible are essential for improvement of quality of care (48). Such measures identify opportunities to improve and direct our attention and resources to areas most needing intervention. In addition, measures of care can be used to evaluate the effects of interventions and guide additional efforts. Quality measurement needs to be part of a larger initiative to educate clinicians about relevant scientific evidence, to engage them in identification of barriers and strategies for improvement in the local setting, implement interventions, and provide feedback about quality and performance with strategies for further improvement (49).

This study has limitations. Perspectives of eligible subjects who could not be recruited might be different from those expressed by participants. Because English fluency was required, we do not have the views of non-English-speaking individuals, whose ICU experiences might be influenced by ethnic and cultural factors and language discordance with care-givers. Comments by some participants may reflect memories of ICU experiences that lost clarity or accuracy over time, or fail to reflect experiences that occurred but were not remembered. Five of our 48 participants were relatives of other participants and therefore may have been predisposed to share views with those others. We sampled three areas of the country and these may not represent norms and values across the US. It was not feasible to perform “member checking” (i.e., reviewing passages with participants for their affirmation), which might have further strengthened our methods ensuring trustworthiness. Exposure to previous research in the field may have unconsciously influenced the approach of the facilitator in focus group meetings or the analysis of transcripts by reviewers. However, we used several strategies to maximize the validity of our methods (50). We used random and representative sampling for recruitment; the cohort included patients and families from multiple ICUs in different hospitals. The same individual facilitated all group meetings; potential facilitator bias was minimized by use of a written guide, emphasis on open-ended questions, and the presence at all meetings of a health care professional from a discipline other than that of the facilitator. After independent coding of verbatim meeting transcripts by three investigators using an inductive, grounded theory method, our analysis reflects an exhaustive process informed and corroborated by multiple sources. The high level of agreement by participants across groups and settings about important attributes of ICU palliative care suggests that we elicited a valid description.

CONCLUSION

Critical care professionals have committed energy and resources to improve quality and safety in every major area of their practice, from ventilator management to prevention of catheter-related bloodstream infection. Recently, several large-scale collaboratives, including the Transformation of the ICU program of the Voluntary Hospital Association, Inc. (12), and a multi-ICU project of Veterans’ Integrated Service Network 3, have turned attention to performance improvement in palliative care, using systems-oriented, pragmatic, interdisciplinary approaches that achieved success in other ICU practice areas (49). It is essential that such efforts focus on aspects of palliative care that are most valued by critically ill patients and their families, among whom we found broad agreement in our sample from heterogeneous institutions. Although the field is relatively young, research has already provided robust evidence for interventions to meet palliative needs in the ICU. With direct information from patients and families who have experienced intensive care for a sustained period, we are in a better position to move ahead with effective implementation.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by R21-AG029955 from the National Institute on Aging (NIA). Dr. Nelson received an Independent Scientist Award from NIA, K02-AG024476. Dr. Penrod was supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Health Services Research and Development Service (project no. REA 08-260). Dr. Nelson and Dr. Pronovost served as consultants to the Voluntary Hospital Association, Inc., a national cooperative of not-for-profit, community-based hospitals, for development of ICU palliative care quality indicators.

The authors are grateful to Elayne Livote, MPH, MS, MA, Veleka Allen, BS, MPH, MS, and Jennifer Kwak, BA, for their assistance with analyses of the participant characteristics and summary of the recruitment; and we thank Daniel Ceusters for technical support.

APPENDIX: SUMMARY OF THE FACILITATOR’S FOCUS GROUP MEETING GUIDE

Initial Open-Ended Questions

Think about your experiences as a patient/family member in the ICU. Focus on care other than medical or surgical treatments to stabilize the patient, reverse the illness, restore physical health, save or prolong life, or prevent complications.

How would you define “high-quality care” by the ICU?

What aspects of your experience in the ICU would you call “high-quality care?”

What aspects of the care did you value the most?

What aspects of the care were (or would have been) most helpful to you?

What aspects of the care had the most impact on your ICU experience?

Probe Items

Are there other aspects/attributes/types of care that you want to include in your definition of “high-quality ICU care”?

Anything related to the patient’s experience of pain or other symptoms (physical or emotional)?

Thoughts about communicating with doctors or nurses or others who work in the ICU?

Aspects related to the process of making decisions about patient care/treatments in the ICU?

Aspects related to the family’s experience?

Comments about spiritual needs of the patient or the family?

What about practical concerns you may have had?

Questions About Clinician Behaviors/Care Processes

Let’s focus directly now on things (actions, behaviors, ways of acting or behaving) that ICU clinicians do (or don’t do) and how those things may relate to your ideas about what is “high-quality ICU care.”

Can you give any examples of things that clinicians in the ICU (doctors, nurses, others) did (actions, behaviors, ways of acting or behaving) that you thought were “high-quality care”?

What other things can you think of (whether they were done or not for you or your loved one) that you consider to be “high-quality ICU care”?

What actions/behaviors by clinicians did you most value?

If you had a “wish list” of things that clinicians in the ICU would do or provide, what would be on that list?

Probe Items Addressing Clinician Behaviors/Care Processes

Are there other actions/behaviors by clinicians that you want to include in your definition of “high-quality ICU care”?

Anything related to the patient’s experience of pain or other symptoms?

Communication/information?

Making decisions about patient care/treatments?

Providing support? What kind?

Probe Items Addressing Specific Care Processes

Let’s focus directly now on some specific things (actions, behaviors) that ICU clinicians do (or don’t do) and how those things may relate (or not) to your ideas about what is “high-quality ICU care.”

Finding out who is the legal decision-maker for the patient (when patient lacks capacity)?

Handing out a printed brochure or leaflet with ICU information? What kind of information?

Meeting with ICU clinicians to discuss the patient’s condition and care?

Making social work support available? Spiritual support?

Inquiring about advance directives?

Asking the views of the patient/family about whether cardiopulmonary resuscitation should be attempted if the patient’s heart stopped?

Evaluating pain? Treating pain?

If you were creating a “report card” for an ICU, what things should be evaluated?

Footnotes

See also p. 987.

Dr. Nelson had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Preliminary data from this study were presented in abstract form at the 2008 American Thoracic Society International Conference

The study was conducted at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York, NY; University of California Medical Center in San Francisco, CA; Norman Regional Hospital in Norman, OK; and the James J. Peters VA Medical Center in Bronx, NY.

The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

The authors have not disclosed any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. [Accessed June 30, 2009];National Priorities Partnership convened by the National Quality Forum. Available online at: http://www.qualityforum.org/about/NPP/

- 2.Field MJ, Cassel CK, editors. Approaching death: Improving care at the end-of-life. Washington DC: National Academy Press; 1997. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Angus DC, Barnato AE, Linde-Zwirble WT, et al. Use of intensive care at the end of life in the United States: An epidemiologic study. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:638–643. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000114816.62331.08. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlet J, Thijs LG, Antonelli M, et al. Challenges in end-of-life care in the ICU/Statement of the 5th International Consensus Conference in Critical Care: Brussels, Belgium, April 2003. Intensive Care Med. 2004;30:770–784. doi: 10.1007/s00134-004-2241-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nelson JE, Danis M. End-of-life care in the intensive care unit: Where are we now? Crit Care Med. 2001;29:N2–N9. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200102001-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. [Accessed June 30, 2009];National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care: Clinical Practice Guidelines for Quality Palliative Care. (2). Available online at: http://www.nationalconsensusproject.org.

- 7.Clarke EB, Curtis JR, Luce JM, et al. Quality indicators for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2003;31:2255–2262. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000084849.96385.85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Teno JM, Casey VA, Welch LC, et al. Patient-focused, family-centered end-of-life medical care: Views of the guidelines and bereaved family members. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2001;22:738–751. doi: 10.1016/s0885-3924(01)00335-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Steinhauser KE, Clipp EC, McNeilly M, et al. In search of a good death: Observations of patients, families, and providers. Ann Intern Med. 2000;132:825–832. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-132-10-200005160-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Singer PA, Martin DK, Kelner M. Quality end-of-life care: Patients’ perspectives. JAMA. 1999;281:163–168. doi: 10.1001/jama.281.2.163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson JE, Angus DC, Weissfeld L, et al. End-of-life care for the critically ill: A national ICU survey. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:2547–2553. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000239233.63425.1D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nelson JE, Mulkerin CM, Adams LL, et al. Improving comfort and communication in the ICU: A practical new tool for palliative care performance measurement and feedback. Qual Saf Health Care. 2006;15:264–271. doi: 10.1136/qshc.2005.017707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mularski RA, Curtis JR, Billings JA, et al. Proposed quality measures for palliative care in the critically ill: A consensus from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Critical Care Workgroup. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S404–S411. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000242910.00801.53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.White DL, Newton-Curtis L, Lyons KS. Development and initial testing of a measure of person-directed care. Gerontologist. 2008;48:114–123. doi: 10.1093/geront/48.supplement_1.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Davidson JE, Powers K, Hedayat KM, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for support of the family in the patient-centered intensive care unit: American College of Critical Care Medicine Task Force 2004–2005. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:605–622. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254067.14607.EB. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Heyland DK, Dodek P, Rocker G, et al. What matters most in end-of-life care: Perceptions of seriously ill patients and their family members. CMAJ. 2006;174:627–633. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.050626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schneiderman LJ, Gilmer T, Teetzel HD, et al. Effect of ethics consultations on nonbeneficial life-sustaining treatments in the intensive care setting: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2003;290:1166–1172. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.9.1166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Campbell ML, Guzman JA. Impact of a pro-active approach to improve end-of-life care in a medical ICU. Chest. 2003;123:266–271. doi: 10.1378/chest.123.1.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lilly CM, De Meo DL, Sonna LA, et al. An intensive communication intervention for the critically ill. Am J Med. 2000;109:469–475. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(00)00524-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lautrette A, Darmon M, Megarbane B, et al. A communication strategy and brochure for relatives of patients dying in the ICU. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:469–478. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa063446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Heyland DK, Rocker GM, O’Callaghan CJ, et al. Dying in the ICU: Perspectives of family members. Chest. 2003;124:392–397. doi: 10.1378/chest.124.1.392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kirchhoff KT, Walker L, Hutton A, et al. The vortex: Families’ experiences with death in the intensive care unit. Am J Crit Care. 2002;11:200–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gelinas C, Fillion L, Puntillo KA, et al. Validation of the critical-care pain observation tool in adult patients. Am J Crit Care. 2006;15:420–427. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Payen JF, Bru O, Bosson JL, et al. Assessing pain in critically ill sedated patients by using a behavioral pain scale. Crit Care Med. 2001;29:2258–2263. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200112000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chanques G, Jaber S, Barbotte E, et al. Impact of systematic evaluation of pain and agitation in an intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:1691–1699. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000218416.62457.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Erdek MA, Pronovost PJ. Improving assessment and treatment of pain in the critically ill. Int J Qual Health Care. 2004;16:59–64. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzh010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mularski RA, Varkey B, Puntillo KA. Pain management within the palliative and end-of-life care experience in the ICU. Chest. 2009;135:1360–1369. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-2328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Puntillo KA, Weiss SJ. Pain: Its mediators and associated morbidity in critically ill cardiovascular surgical patients. Nursing Research. 2004;43:31–36. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hawryluck LA, Harvey WR, Lemieux-Charles L, et al. Consensus guidelines on analgesia and sedation in dying intensive care unit patients. BMC Med Ethics. 2002;3:E3. doi: 10.1186/1472-6939-3-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azoulay E, Pochard F, Chevret S, et al. Impact of a family information leaflet on effectiveness of information provided to family members of intensive care unit patients: A multicenter, prospective, randomized, controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;165:438–442. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.165.4.200108-006oc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gay E, Pronovost P, Bassett R, et al. The ICU family meeting: Making it happen. J Crit Care. 2009 Feb 12; doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2008.10.003. [Epub head of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Curtis JR, White DB. Practical guidance for evidence-based ICU family conferences. Chest. 2008;134:835–843. doi: 10.1378/chest.08-0235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nelson J, Walker AS, Luhrs CA, et al. Making family meetings simpler: A toolkit for the ICU. J Crit Care. 2009 doi: 10.1016/j.jcrc.2009.02.007. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Billings JA, Keeley A, Bauman J, et al. Merging cultures: Palliative care specialists in the medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:S388–S393. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000237346.11218.42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ross MW. Implementing a bereavement program. Crit Care Nurse. 2008;28:87–88. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Siegel MD, Hayes E, Vanderwerker LC, et al. Psychiatric illness in the next of kin of patients who die in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:1722–1728. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e318174da72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang B, El-Jawahri A, Prigerson HG. Update on bereavement research: Evidence-based guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of complicated bereavement. J Palliat Med. 2006;9:1188–1203. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.1188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fauri DP, Ettner B, Kovacs PJ. Bereavement services in acute care settings. Death Stud. 2000;24:51–64. doi: 10.1080/074811800200694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Garrouste-Org, Philippart F, Timsit JF, et al. Perceptions of a 24-hour visiting policy in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2008;36:30–35. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000295310.29099.F8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Davidson JE. Presence of family liaison might build case for family presence. Am J Crit Care. 2007;16:333–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fumagalli S, Boncinelli L, Lo NA, et al. Reduced cardiocirculatory complications with unrestrictive visiting policy in an intensive care unit: Results from a pilot, randomized trial. Circulation. 2006;113:946–952. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.572537. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee MD, Friedenberg AS, Mukpo DH, et al. Visiting hours policies in New England intensive care units: Strategies for improvement. Crit Care Med. 2007;35:497–501. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000254338.87182.AC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Berwick DM, Kotagal M. Restricted visiting hours in ICUs: Time to change. JAMA. 2004;292:736–737. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.6.736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McAdam JL, Arai S, Puntillo KA. Unrecognized contributions of families in the intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2008;34:1097–1101. doi: 10.1007/s00134-008-1066-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pronovost PJ, Miller MR, Dorman T, et al. Developing and implementing measures of quality of care in the intensive care unit. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2001;7:297–303. doi: 10.1097/00075198-200108000-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Brook RH, McGlynn EA, Cleary PD. Quality of health care. Part 2: Measuring quality of care. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:966–97. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199609263351311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Donabedian A. Evaluating the quality of medical care. Milbank Mem Fund Q. 1966;44:166–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Care and Communication Quality Measures at the National Quality Measures Clearing-house sponsored by the Agency for Health-care Research and Quality. [Accessed June 30, 2009]; Available online at: http://www.qualitymeasures.ahrq.gov.

- 49.Pronovost PJ, Berenholtz SM, Needham DM. Translating evidence into practice: A model for large-scale knowledge translation. BMJ. 2008;337:a1714. doi: 10.1136/bmj.a1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Giacomini MK, Cook DJ. Users’ guides to the medical literature: XXIII. Qualitative research in health care A. Are the results of the study valid? Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA. 2000;284:357–362. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.3.357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]