Abstract

Although oligomeric intermediates are transiently formed in almost all known amyloid assembly reactions, their mechanistic roles are poorly understood. Recently we demonstrated a critical role for the 17 amino acid N-terminal segment (httNT) of huntingtin (htt) in oligomer-mediated amyloid assembly of htt N-terminal fragments. In this mechanism, the httNT segment forms the α-helix rich core of the oligomers, leaving most or all of each polyglutamine (polyQ) segment disordered and solvent-exposed. Nucleation of amyloid structure occurs within this local high concentration of disordered polyQ. Here we demonstrate the kinetic importance of httNT self-assembly by describing inhibitory httNT-containing peptides that appear to work by targeting nucleation within the oligomer fraction. These molecules inhibit amyloid nucleation by forming mixed oligomers with the httNT domains of polyQ-containing htt N-terminal fragments. In one class of inhibitor, nucleation is passively suppressed due to the reduced local concentration of polyQ within the mixed oligomer. In the other class, nucleation is actively suppressed by a proline-rich polyQ segment covalently attached to httNT. Studies with D-amino acid and scrambled sequence versions of httNT suggest that inhibition activity is strongly linked to the propensity of inhibitory peptides to make amphipathic α-helices. HttNT derivatives with C-terminal cell penetrating peptide segments, also exhibit excellent inhibitory activity. The httNT-based peptides described here, especially those with protease-resistant D-amino acids and/or with cell penetrating sequences, may prove useful as lead therapeutics for inhibiting nucleation of amyloid formation in Huntington’s disease.

Keywords: amyloid, polyglutamine, inhibitor, α-helical intermediate, cell penetrating peptide

In Huntington’s disease (HD), inheritance of an expanded version of a polyglutamine (polyQ) encoding CAG repeat in the gene for the ~ 3,200 amino acid huntingtin (htt) protein is tightly linked to devastating neurodegeneration 1. As in the case of the eight or nine 2 other expanded CAG repeat diseases, various aggregated forms (i.e., larger than monomer) of htt are found in brain tissue from patients and from experimental animals 3; 4. A strong correlation in vitro 5; 6 and in vivo 7 between polyQ repeat expansion and aggregation provided further links between pathology and protein misfolding and/or aggregation 8; 9; 10. Many studies in a variety of mutant htt-expressing model organisms, including transgenic mice 11; 12; 13; 14; 15, report the detection in the brain of insoluble and/or aggregated forms of huntingtin occurring roughly in the same time frames as the development of disease symptoms. Although correlations between the appearance of aggregates and of pathology in cell and animal models are not universally observed 16, this may be due in part to current limitations on our ability to observe micro-aggregates in cells and/or tissues. In any case, it is clear that more work must be done to further probe the roles of aggregated huntingtin in the HD mechanism. One approach to testing this hypothesis is to develop tools for preventing or changing the course of aggregation in cell and animal models.

The N-terminal 3% of the huntingtin protein consists of a 17-amino acid N-terminus (the httNT segment) followed by the polyQ repeat, followed by a proline-rich segment 11. The remaining 97% of htt appears to be rich in HEAT repeats often involved in assembly of protein complexes, but has no other evident folding units 17; 18. Proteolytic events that release, from full-length htt, N-terminal fragments that contain the httNT, polyQ and Pro-rich segments have been implicated as an early step in pathogenesis 19; 20, and transgenic animals expressing similar short, N-terminal fragments exhibit particularly aggressive neuropathology 1; 21. These observations together suggest that some property of htt that is enhanced in polyQ-containing N-terminal fragments must play an important role in disease.

Simple polyQ peptides aggregate according to a classical nucleated growth polymerization mechanism with no non-amyloid intermediates 22; 23; 24; 25; 26; 27. Some polyQ flanking sequences, however, can substantially alter polyQ aggregation mechanism and/or kinetics 28; 29; 30; 31; 32; 33. In particular, the N-terminal httNT segment of htt has a dramatic enhancing effect on the aggregation and toxicity of polyQ.

The httNT segment possesses a mix of hydrophobic and hydrophilic amino acids (Table 1) and is predicted to have both significant α-helix potential 34; 35; 36 and a moderate tendency toward compact structure 32, two characteristics typical of MoRF sequences 37. MoRF (Molecular Recognition Features) sequence elements exist in isolation as intrinsically disordered elements, but can acquire structure in the presence of a binding partner 38. Thus, proton NMR shows that there is no stable secondary structure in this peptide in native aqueous solutions 32, but CD spectra 32; 34 and MD simulations 36 suggest that the httNT sequence by itself has a tendency to take on some α-helical secondary structure. In spite of, or perhaps because of, this ambiguous structure, the short httNT sequence appears to play an important role in the biological life of the huntingtin protein. Post-translational modifications of the httNT sequence in full-length or N-terminal fragments of htt, in cell and animal models, have been implicated in playing important roles in normal and abnormal htt cell biology and in htt pathology 15; 35; 39; 40; 41.

Table 1.

Peptide sequences studied

| Name | Sequence |

|---|---|

| HttNT | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSF |

| HttNTQ3 (F17W) | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ |

| HttNTG5K8 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSFGGG GGKKKKKKKK |

| HttNTG4CK8 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSFGGG GCKKKKKKKK |

| HttNTQ30P6K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSFQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQPPP PPPKK |

| HttNTQ30P6K2 (F17W) | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQPPP PPPKK |

| HttNTQ30P10K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSFQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQPPP PPPPPPPKK |

| HttNTQ37P10K2 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSFQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQPPPPPP PPPPKK |

| SWQ37P10K2 | SWQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQ PPPPPPPPPP KK |

| K2Q35P10K2 | KKQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQPPP PPPPPPPKK |

| K2Q41K2 | KKQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQQQQQQQQ QQQKK |

| PGQ9P1,2,3 | KKQQQQPQQQ QPGQQQQPQQ QQPGQQQQPQ QQQPGQQQQQ QQQQKK |

| HttNTPGQ9P1,2,3 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSFQQQ QPQQQQPGQQ QQPQQQQPGQ QQQPQQQQPG QQQQQQQQQK K |

| HttNTPGQ9P1,2,3 (F17W) | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSWQQQ QPQQQQPGQQ QQPQQQQPGQ QQQPQQQQPG QQQQQQQQQK K |

| HttNTPGQ9P1,2,3K8 | MATLEKLMKA FESLKSFQQQ QPQQQQPGQQ QQPQQQQPGQ QQQPQQQQPG QQQQQQQQQK KKKKKKK |

Consistent with this, the httNT segment exhibits a striking effect on polyQ aggregation 32; 42. Peptides with the structure httNTQN aggregate with much higher rates than the identical repeat length simple polyQ sequences at similar concentrations 32. They accomplish this via a radically altered aggregation mechanism. Thus, httNTQN peptides first assemble into small, oligomeric structures that serve as the medium within which nucleation of amyloid structure occurs 32. In these oligomers, consistent with their MoRF-like character, the httNT segments self-associate to form an α-helix rich 43(Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted) core from which unstructured polyQ is largely excluded 32. Presumably facilitated by the high local concentration of disordered polyQ, amyloid structure is nucleated within some of these oligomers, leading to a burst in aggregation rate 32 and a polyQ-repeat length dependent transition from α-helix-rich to β-sheet-rich aggregate (M. Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted).

In this paper we show that the aggregation of htt N-terminal fragments can be strongly inhibited by molecules that compromise the role these α-helix rich oligomers play in the aggregation mechanism. We show that the httNT peptide itself, with or without very short polyQ extensions, co-assembles with httNTQN peptides to make mixed oligomers whose nucleation efficiency is much reduced, presumably due to the reduction in the local concentration of polyQ within the oligomers. We also show that even greater inhibition can be obtained if a Pro-containing polyQ sequence 23 is attached to the httNT, creating a molecule that can co-assemble into oligomers with htt N-terminal fragments where it actively inhibits polyQ amyloid nucleation. Further experiments with sequence analogs of httNT suggest that httNT co-assembly depends on the ability of this sequence to form amphipathic α-helix. These httNT-related molecules exhibit a novel means of inhibiting htt amyloid assembly, providing insights into the normal aggregation mechanism as well as potential tools for both understanding the molecular basis of expanded polyQ pathogenicity and for drug discovery. In fact, modifications designed to improve the cell uptake and stability of these peptides were found to not disrupt their inhibitory activities.

RESULTS

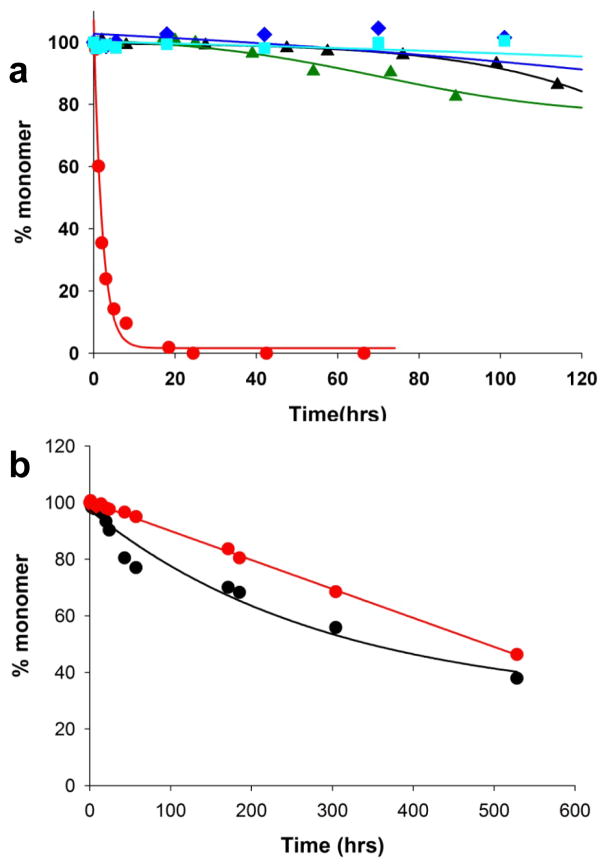

After discovering that the httNT component in cis confers onto polyQ a dramatic increase in aggregation kinetics with a substantial change in mechanism 32, we conducted experiments to test whether this effect might operate in trans as well. An example of the strong cis effect is shown in Figure 1a, where the htt N-terminal fragment httNTQ37P10K2 (

) aggregates to completion over a period of a few hours, while similar peptides lacking some (

) aggregates to completion over a period of a few hours, while similar peptides lacking some (

) or all (▴) of the httNT sequence do not progress beyond 20% aggregation even after 120 hrs. In contrast, we observe no trans effect, in that an equimolar amount of httNT incubated with the K2Q41K2 peptide (

) or all (▴) of the httNT sequence do not progress beyond 20% aggregation even after 120 hrs. In contrast, we observe no trans effect, in that an equimolar amount of httNT incubated with the K2Q41K2 peptide (

) produces no change in the relatively slow aggregation rate seen for the K2Q41K2 peptide alone (

) produces no change in the relatively slow aggregation rate seen for the K2Q41K2 peptide alone (

) (Fig. 1a). This latter result is in contrast to a recent report claiming such a trans effect 42. Because this recent contradictory report was based on a significantly modified polyQ peptide 42, we considered the possibility that the discrepancy in results might derive from major differences in the sequence context of the polyQ peptides in the two studies. We therefore obtained by chemical synthesis exactly the same sequence reported to be enhanced by httNT in trans 42 and studied its aggregation. We found that the peptide alone aggregates slowly (Fig. 1b, ●), at an initial rate that is comparable to that of a simple polyQ peptide of similar repeat length and concentration 27. We also found, however, that equimolar httNT, if anything, slightly inhibits aggregation of this peptide (Fig. 1b,

) (Fig. 1a). This latter result is in contrast to a recent report claiming such a trans effect 42. Because this recent contradictory report was based on a significantly modified polyQ peptide 42, we considered the possibility that the discrepancy in results might derive from major differences in the sequence context of the polyQ peptides in the two studies. We therefore obtained by chemical synthesis exactly the same sequence reported to be enhanced by httNT in trans 42 and studied its aggregation. We found that the peptide alone aggregates slowly (Fig. 1b, ●), at an initial rate that is comparable to that of a simple polyQ peptide of similar repeat length and concentration 27. We also found, however, that equimolar httNT, if anything, slightly inhibits aggregation of this peptide (Fig. 1b,

), rather than enhancing it. It is not clear why the results of Tam et al. 42 differ from ours; it might be due to differences in peptide handling or substantial differences in the aggregation assay.

), rather than enhancing it. It is not clear why the results of Tam et al. 42 differ from ours; it might be due to differences in peptide handling or substantial differences in the aggregation assay.

Figure 1.

Kinetic effects of httNT on aggregation of polyQ-containing peptides by the sedimentation assay. (a) Aggregation of 23.3 μM httNTQ37P10K2 (

); 25.2 μM SWQ37P10K2 (

); 25.2 μM SWQ37P10K2 (

); 25.6 μM K2Q35P10K2 (▴); 7.5 μM K2Q41K2 alone (

); 25.6 μM K2Q35P10K2 (▴); 7.5 μM K2Q41K2 alone (

); and 7.0 μM K2Q41K2 plus 17.4 μM httNT (

); and 7.0 μM K2Q41K2 plus 17.4 μM httNT (

). (b) Aggregation of 18.8 μM of the peptide ESLKSF-Q35-PPPSKETAAAKFERQHMDS incubated alone (●) or with 29.6 μM httNT (

). (b) Aggregation of 18.8 μM of the peptide ESLKSF-Q35-PPPSKETAAAKFERQHMDS incubated alone (●) or with 29.6 μM httNT (

).

).

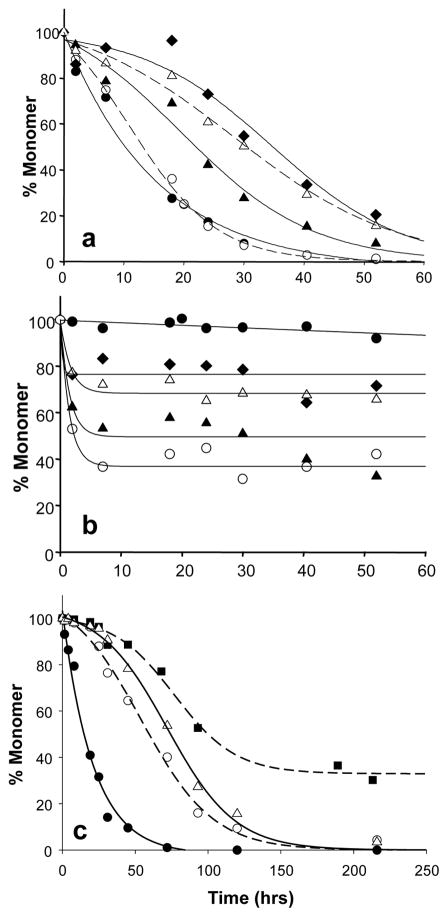

In any case, as a control in the Figure 1 experiments, we also incubated httNT with the htt N-terminal fragment httNTQ30P6K2 and found, surprisingly, that httNT inhibits aggregation of this htt N-terminal fragment in a concentration-dependent manner (Fig. 2a). Furthermore, early in the inhibited reaction, a portion of the httNT inhibitor becomes susceptible to sedimentation (Fig. 2b), suggesting possible formation of a co-aggregate between httNT and httNTQ30P6K2 (compare Fig. 2b to Fig. 2a). After this initial drop, little or no additional httNT co-aggregates. Note that in the absence of httNTQ30P6K2, very little httNT aggregates under these conditions (Fig. 2b, ●). The inhibition of httNTQ30P6K2 aggregation by httNT can be characterized as a delay in the inevitable; that is, although increasing concentrations of httNT lead to longer delay times in the aggregation reaction, robust aggregation nonetheless eventually occurs, going essentially to completion regardless of the amount of httNT inhibitor present (Fig. 2a). This is also true when a stoichiometric excess of httNT over httNTQ30P6K2 is used (Fig. 2c). Further, multiple equimolar doses of httNT given over the reaction time course further slow aggregation, so that, within the reaction time monitored, amyloid formation did not go to completion (Fig. 2c, ■).

Figure 2.

HttNT inhibition of aggregation. (a, b) Incubation of 9 μM httNTQ30P6K2 with different molar ratios of httNT to httNTQ30P6K2: 0.05:1 (○); 0.16:1 (▴); 0.43:1 (▵); 0.89:1 (◆). (a) Soluble httNTQ30P6K2 after centrifugation; control incubation of httNTQ30P6K2 without inhibitor (●); (b) Soluble httNT inhibitor after centrifugation; control incubation of httNT alone (●); (c) Effect of higher ratios and multiple additions of httNT on httNTQ30P6K2 aggregation: 7.0 μM httNTQ30P6K2 alone (●); 5.33 μM httNTQ30P6K2 with either 7.5 μM httNT (i.e., ~ 1.4 fold molar excess) (○) or 13.3 μM httNT (i.e., ~ 2.5 fold molar excess) (▵) added at t = 0; 5.33 μM httNTQ30P6K2 plus 7.5 μM httNT reaction in which fresh, additional aliquots of httNT were added at 7 hrs (11.2 μM), 24 hrs (7.0 μM), 31 hrs (7.3 μM), and 68 hrs (6.4 μM) (■). Peptides were incubated at 37 °C in PBS, with aggregation monitored by the sedimentation assay.

Mechanism of inhibition

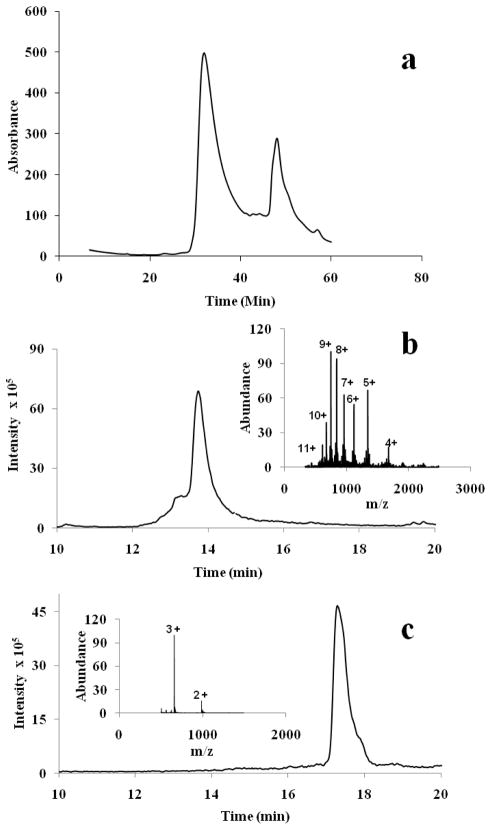

To probe the mechanism of these inhibitory effects, we first tested whether httNT can form mixed low MW co-oligomers, such as heterodimer, with httNTQ30P6K2. We incubated a mixture of these two peptides and subjected the mixture to size exclusion chromatography (SEC) with the column fractions being subjected to LC—MS analysis (Fig. 3). The SEC profile shows two major peaks eluting at the MW positions of monomeric httNTQ30P6K2 and httNT (Fig. 3a). Each peak was collected and injected into an analytical reverse phase HPLC column with MS detection. We found that the early eluting SEC peak (Fig. 3a) gives LC-MS data consistent with homogeneous httNTQ30P6K2 (Fig. 3b), and the later eluting peak gives data consistent with homogeneous httNT (Fig. 3c). Thus, there is no evidence for stable low MW complexes of these two proteins, which, if present, should elute earlier than httNTQ30P6K2 in Figure 3a and give LC-MS signals for both peptides in the same SEC fraction. This experiment does not rule out the possible existence of stable complexes that do not chromatograph well, or of less stable complexes that might disintegrate early in the SEC run time.

Figure 3.

The SEC profile of an incubated mixture of httNTQ30P6K2 (F17W) and httNT was analyzed by LC-MS. The peak eluting at ~ 32 mins gave the HPLC profile shown in part B, and the mass spectrum at the intensity peak (inset) gave a mass of 6697 Da consistent with httNTQ30P6K2 (F17W). The peak eluting at ~49 mins gave the HPLC profile shown in Part C, and the mass spectrum at the intensity peak (inset) gave a mass of 1972.8 Da, consistent with httNT. The absence of a SEC peak containing both peptides indicates that there is no significant low molecular weight complex formation under these conditions.

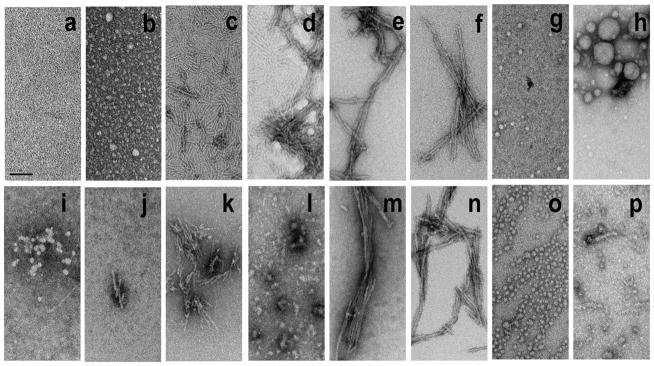

Although the above experiment suggests that these two peptides do not form stable, low MW complexes with each other, electron microscopy suggests that upon incubation they quickly form large spherical co-oligomers. As reported previously for other htt N-terminal fragments, we found that httNTQ30P6K2 incubated alone forms small spherical oligomers within 15 mins of incubation (Fig. 4b), to be replaced at 5.5 hrs with small fibril structures (Fig. 4c) that eventually grow to intermediate fibrils at 24 hrs (Fig. 4d) and longer and thicker fibrils (Fig. 4e, f) at later times. In contrast, when co-incubated with httNT, some of the early oligomers are much larger (Fig. 4g, h) and persist long beyond 15 mins, exhibiting a mixture of oligomers (Fig. 4i,l) and fibrils (Fig. 4j,k) at both 5.5 (Fig. 4i,j) and 24 (Fig. 4k,l) hrs, before reaching a point of uniform fibril morphology at 48 (Fig. 4m) and 72 (Fig. 4n) hrs that is indistinguishable from httNTQ30P6K2 alone (Fig. 4e,f). In contrast, as previously reported, httNT incubated by itself aggregates very slowly, forming oligomeric clusters only after hundreds of hours of incubation 32. The uncharacteristically large oligomers uniquely formed rapidly in the httNT inhibited httNTQ30P6K2 aggregation reaction suggest that these oligomers represent co-aggregates of the two component peptides.

Figure 4.

Electron micrographs of aggregates of htt N-terminal fragments. Aggregates from HttNTQ30P6K2 alone incubated in PBS at 37 °C and sampled at 0 hrs (a), 15 min (b), 5.5 hrs (c), 24 hrs (d), 48 hrs (e), and 100 hrs (f). HttNTQ30P6 incubated with httNT in 1:1 ratio in PBS, 37 °C and sampled at 3 hrs (g, h), 5.5 hrs (i, j), 24 hrs (k, l), 48 hrs (m) and 72 hrs (n). httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 incubated alone for 120 hrs (o), httNTQ30P6K2 and httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 co-incubated in 1:4 ratio in PBS, 37 °C for 120 hrs (p). Scale bar represents 50 nm.

Confirmatory evidence for co-aggregate formation comes from experiments with peptides containing an F17W replacement within the httNT component. Previously we used tryptophan intrinsic fluorescence to probe the burial of a Trp probe in aggregate structure 32. Here, when we incubated a 1:1 mix of httNTQ30P6K2 and httNT (F17W) for 4 hrs, a time frame when only oligomers are present by EM (Fig. 4g,h), we found that the isolated aggregates exhibit strong Trp fluorescence (Fig. 5a, blue) consistent with the presence of the httNT inhibitor in the aggregate. Since httNT peptides incubated in isolation aggregate only very slowly 32, to find httNT (F17W) fluorescence in the early aggregate pool suggests that its aggregation has been somehow stimulated by the presence of httNTQ30P6K2, and the simplest rationale for such stimulation is co-aggregation with httNTQ30P6K2. This indirect evidence for an intimate co-aggregate is confirmed by the details of the fluorescence spectrum.

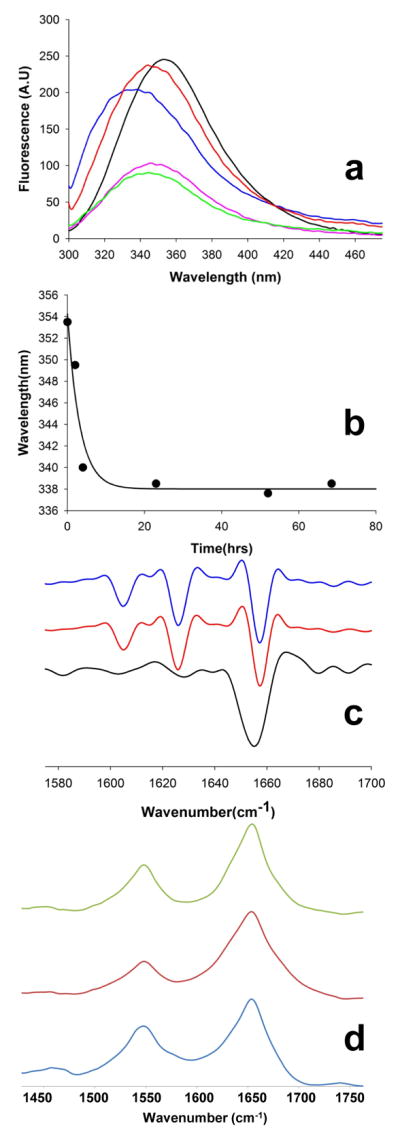

Figure 5.

Spectroscopic probes of aggregate structure. (a) Tryptophan fluorescence spectra of isolated and resuspended aggregates from the following reactions: monomeric httNTQ30P6K2 (F17W), λem = 355 nm (black); aggregated httNTQ30P6K2 (F17W) alone, λem = 347.5 nm, (green); httNT plus httNTQ30P6K2 (F17W), λem = 349 nm, (magenta); httNTQ3 (F17W) inhibitor plus httNTQ30P6K2, λem = 337 nm, (blue); httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 (F17W) plus httNTQ30P6K2, λem = 347.5 nm, (orange). (b) Time course of the Trp fluorescence peak shift in isolated aggregates when the httNTQ3 (F17W) inhibitor is incubated with httNTQ30P6K2 at a 1.1:1 ratio; (c) Second deriviative FTIR spectra of aggregates isolated at about 100 hrs from incubation reactions of httNT (black), httNTQ30P6K2 (red), and a reaction with a 1:1 mixture of httNT and httNTQ30P6K2 (blue); (d) primary FTIR spectra of aggregates generated upon incubation of either all-L httNT (blue), all-D httNT (red), and retro-inverso httNT (green).

While Trp is solvent exposed (i.e., the fluorescence maximum is 355 nm, unshifted from that of the monomer 32) in oligomers slowly produced when httNT (F17W) is incubated alone 32, the Trp fluorescence of rapidly formed aggregates isolated from the co-mixture with httNTQ30P6K2 (Fig. 5a, blue) is dramatically shifted to 337 nm, indicating a solvent-excluded environment for the Trp in these aggregates. These aggregates are almost certainly oligomeric (i.e., not fibrillar), since the time course of the fluorescence shift within the aggregate fraction goes essentially to completion within 5 hrs (Fig. 5b); in equivalent reactions, the aggregates at 5 hrs are mostly oligomeric (Fig. 4), and the rapid amyloid formation phase has not yet commenced (Fig. 2a). These data suggest that httNT (F17W) forms aggregates in this mixed reaction via an intimate oligomeric co-aggregate with httNTQ30P6K2. Interestingly, the fluorescence maximum for the co-mixture of httNT and httNTQ30P6K2 is much more shifted when Trp17 is in the inhibitor (Fig. 5a, blue, 337 nm) than when it is in the httNTQ30P6K2 (Fig. 5a, magenta, 349 nm). Thus, the local environment around position 17 in the httNT inhibitor is solvent-excluded in co-aggregates with a huntingtin fragment, a qualitatively different result from either aggregates of httNT alone 32 or co-aggregates in which it is the httNTQ30P6K2 peptide that contains a Trp (Fig. 5a, magenta).

In contrast to these oligomeric intermediates, the final aggregated product of httNT-inhibited reactions is amyloid in nature, and is in fact indistinguishable from the product of the uninhibited reaction, by FTIR (Fig. 5c) as well as EM (Fig. 4). While, as previously reported 43, the slowly formed aggregates of httNT incubated alone are rich in α-helix by FTIR (Fig. 5c, black), the spectrum of httNTQ30P6K2 aggregates (Fig. 5c, red) is dominated by the three bands characteristic of polyQ amyloid absorbing at 1604.6 cm−1 (Gln side chain N-H bending), 1626 cm−1 (β-sheet), and 1656.8 cm−1 (Gln side chain C=O stretching). The FTIR spectrum of the final aggregated product of the httNT-inhibited reaction of httNTQ30P6K2 (Fig. 5c, blue) is identical to that of the uninhibited aggregation product. (Because of the very small mass of oligomeric co-aggregates formed in the inhibited reactions, it has not been possible to obtain FTIR spectra on these pre-amyloid assemblies.)

These data support a model in which httNT inhibitors co-assemble with the httNT segments of httNTQ30P6K2 peptides into mixed, α-helix rich oligomers, thereby decreasing the local concentration of exposed polyQ segments in comparison to homogeneous httNTQ30P6K2 oligomers; this reduced local polyQ concentration restricts the polyQ interchain interactions that drive nucleation of amyloid structure 32. To further characterize this proposed mechanism, we conducted a detailed series of experiments with structurally modified httNT analogs.

Structure-function relationships in httNT inhibition

To investigate the structural specificity of httNT inhibition, we obtained an all-D version of httNT as well as a “retro-inverso” 44 version of httNT, in which the httNT sequence is not only constructed with D amino acids but is also inverted (Table 1). Such retro-inverso peptides are sometimes used in an attempt to partially restore the side chain orientations of the wild type all-L peptide in an all-D peptide analog 44. {It should be noted that optimal retro-inverso sequences also include modifications at the N- and C- termini to restore the terminal charge identity, with respect to sequence, found in the parent, L-version 45; this was not done in our peptide.} Our expectation in designing this experiment was that there must be important stereochemical specificity in httNT mixed oligomer formation that would be compromised when D-httNT interacts with L-httNTQN. We were therefore surprised to find that both the all-D and retro-inverso versions of httNT are also effective inhibitors of L-htt N-terminal fragment aggregation (Fig. 6a). In this experiment we used the slower aggregating P10 version of the Q30 N-terminal fragment, which probably explains the apparently improved inhibition by the all-L httNT peptide in this experiment. In any case, under the same conditions, both the all-D and the retro-inverso versions of httNT are equally effective inhibitors of httNTQ30P10K2 aggregation (Fig. 6a). Consistent with our hypothesis that inhibition requires the ability to form an α-helix rich oligomer, we found that the all-D and retro-inverso forms of httNT form aggregates at the same slow rates (not shown) as seen previously for all-L httNT (Fig. 2b), and that FTIR spectra of the aggregates formed are identical to aggregates of all-L httNT (Fig. 5d) in suggesting highly α-helical structures.

Figure 6.

Abilities of approximately equimolar httNT analogs to inhibit aggregation of htt N-terminal fragments in PBS at 37 °C, as determined by a sedimentation assay. (a) inhibition of 7.6 μM httNTQ30P10K2 aggregation by all-L httNT (15 μM), all-D httNT (11.1 μM) and retroinverso-httNT (9.5 μM) (b, c) inhibition of 5–10 μM httNTQ30P6K2 aggregation by 1:1 molar amounts of wild type and scrambled httNTQ sequences.

One interpretation of this result is that the inhibition we observe with httNT has no real structural specificity, and may simply depend on the net hydrophobicity and charge characteristics of this collection of amino acids in a short peptide. To test this hypothesis, we designed and obtained a series of scrambled sequence variants of the inhibitory peptide httNTQ. A list of 49 random sequences (Supporting Table 1) was generated using MATLAB (Methods). This list was then visually edited (Methods) to produce 20 scrambled sequences with a variety of distributions of charged and hydrophobic residues (Supporting Table 1). These 20 sequences (Table 2) were obtained by custom synthesis and purified by HPLC (Methods). Some of the peptides gave inadequate yields after purification and were not pursued. In addition, two of the peptides co-migrated in HPLC with the htt N-terminal fragment aggregation substrate, complicating aggregation kinetics analysis, and were therefore not pursued. Three others readily grew into amyloid fibrils under PBS, 37 °C conditions and were not pursued as part of these experiments. After attrition of candidate peptides for the above reasons, we were left with 10 scrambled peptides (Table 2) amenable to further analysis, and these were tested, along with control httNT, as potential inhibitors of httNTQ30P6K2 (Fig. 6b,c) at a 1:1 stoichiometric ratio. Of these 11 peptides, the wild type httNT sequence (○) proved to be the best inhibitor. Furthermore, five of the random peptides (peptides # 2, 4, 5, 6, and 9) exhibited no inhibitory activity under these conditions. Interestingly, however, the other five peptides (# 3, 7, 8, 11, and 12) gave good to very good inhibitory activity, with one inhibitor, peptide # 11, delaying the time to 50% aggregation almost as long as httNT itself (Fig. 6c; Table 2).

Table 2.

Sequences and properties of scrambled httNT sequence peptidesa

| Peptide Number | Sequence | AGADIR scoreb | % helix, CDc | Hydrophob. moment (μH)d | t½ e |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WT | MATLEKLMKAFESLKSF | 4.27 | 8.7 | 0.398 | 90 |

| 2 | MLSLKESAKMFFATKELQ | 0.49 | 4.3 | 0.118 | 20 |

| 3 | KQFTLEMAFLSKALSEMK | 1.74 | 8.7 | 0.342 | 40 |

| 4 | KLAFMLKQAELSSEKTFM | 0.60 | 5.3 | 0.154 | 25 |

| 5 | FAKFASEKKLESMTLMLQ | 0.56 | 3.5 | 0.092 | 18 |

| 6 | MLTFAEFKSMELKSQLAK | 1.12 | 0.0 | 0.137 | 20 |

| 7 | ASMFEAQLSKEKKMFTLL | 1.60 | 8.7 | 0.335 | 60 |

| 8 | ELLAKSEQAKSMLFTFMK | 0.59 | 3.9 | 0.305 | 35 |

| 9 | TKFSSFALLAQKEMLKME | 1.29 | 6.2 | 0.203 | 25 |

| 11 | ASSQKKMKEMLAFFTLEL | 2.97 | 5.8 | 0.287 | 80 |

| 12 | MFSKMAKSLFLLAEKTQE | 1.10 | 3.7 | 0.414 | 50 |

| - | No addition | - | 20 |

Scrambled sequence peptides, plus wild type httNT, investigated for ability to inhibit aggregation of httNTQ30P6K2 when present in 1:1 stoichiometry. Not shown are peptides that exhibited poor synthetic yields, co-migration with httNTQ30P6K2 in analytical HPLC, or facile amyloid formation when incubated alone in PBS at 37 °C.

See Methods.

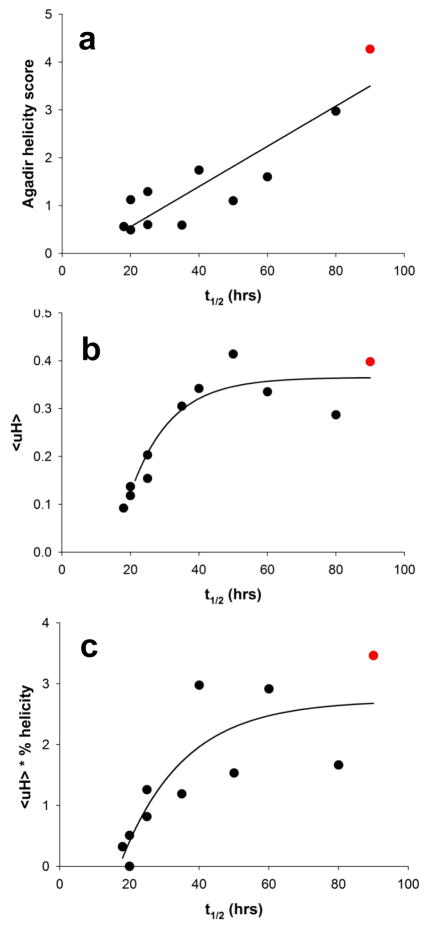

This scrambed sequence experiment produced the counter-intuitive result that while httNT inhibition is impervious to a universal L to D switch at the amino acid level (Fig. 6a), it nonetheless exhibits significant sequence selectivity within a series of scrambled sequences. One possible way to rationalize these two sets of results is the hypothesis that inhibition depends on the formation of an α-helix displaying a particularly effective pattern of surface charge and/or hydrophobicity, a condition unlikely to be equally achievable by all of scrambled sequences. To test this α-helix hypothesis, we first calculated an α-helix potential for each scrambled sequence using AGADIR 46 (Table 2). A plot of these values against the inhibitory activities (time to 50% aggregation; Table 2) of the each peptide (Fig. 7a) shows a good linear correlation with R2 = 0.80. We next considered whether the amphipathicity or hydrophobic moments 47 of such α-helices might play a role in inhibitory activity. We calculated the hydrophobic moments (μH) of α-helices populated by the different scrambled sequences (Table 2) and plotted the results against inhibitory activity. The results (Fig. 7b) show a very good correlation with R2 = 0.88. Based on these encouraging results, we determined CD spectra of each scrambled peptide alone at 100 μM and calculated the % α-helix (Methods) (Table 2). The actual predicted α-helix formation for each peptide was then used to normalize the hydrophobic moment values (which of course are obtained by assuming 100% α-helix formation) and the resulting “normalized μH” values were plotted against inhibitory activity. The results (Fig. 7c) exhibit a good correlation with R2 = 0.70. This latter plot features a very good correlation among peptides with very low α-helix potential, consistent with the importance of α-helix formation in the mechanism of inhibition. It also links the highest normalized μH with the highest inhibitory activity, corresponding to the wild type sequence (

). At the same time, the higher departure from the fitted line among the more strongly inhibiting peptides shows that the calculated normalized μH values have a lower predictive value in this regime. There are several possible explanations for this. It might be due to experimental uncertainty in the α-helix contents calculated from the CD spectra. It is also quite likely that estimates of α-helix formation in these peptides as monomers in solution poorly describes their ultimate abilities to form α-helix when mixed with htt N-terminal fragments. Finally, it is likely that gross amphipathicity is not an adequate description of optimal hydrophobic topology for mixed oligomer formation and inhibition.

). At the same time, the higher departure from the fitted line among the more strongly inhibiting peptides shows that the calculated normalized μH values have a lower predictive value in this regime. There are several possible explanations for this. It might be due to experimental uncertainty in the α-helix contents calculated from the CD spectra. It is also quite likely that estimates of α-helix formation in these peptides as monomers in solution poorly describes their ultimate abilities to form α-helix when mixed with htt N-terminal fragments. Finally, it is likely that gross amphipathicity is not an adequate description of optimal hydrophobic topology for mixed oligomer formation and inhibition.

Figure 7.

Scatterplot analyses of inhibitory activities of wild type httNT and scrambled peptides (Table 2). (a) aggregation inhibition vs. AGADIR α-helix propensity (linear fit; R2 = 0.80); (b) aggregation inhibition vs. hydrophobic moment (μH) score (exponential fit; R2 = 0.88); (c) aggregation inhibition vs. normalized μH values determined by multiplying the hydrophobic moment times the measured % α-helix as determined by CD spectroscopy (three parameter exponential fit; R2 = 0.70) (see Table 2). In each plot the position of the httNT wild type sequence is in red.

In spite of the imperfect correlation with α-helix parameters, overall – given the established structures of the httNT oligomers and the strong inhibitory activity of the D-versions of httNT - the data imply an important role for amphipathic helix formation in controlling the ability of peptides to inhibit the aggregation of htt N-terminal fragments.

Hybrid inhibitors

As shown in Figure 2, under most conditions httNT inhibitors are effective at delaying nucleation of amyloid formation in htt N-terminal fragment peptides, but cannot completely eliminate nucleation. This is likely because of the statistical probability that nucleation will at some point occur even within mixed oligomers, especially the sub-population of oligomers containing a relatively low percentage of inhibitor molecules. We hypothesized that nucleation inhibition might be enhanced if the inhibitor httNT peptide were fused to a powerful elongation inhibitor. We previously described such elongation inhibitors, in the form of mutated polyQ peptides that contain not only regularly spaced Pro-Gly residues, to dictate the points at which the chain can form β-turns, but also intervening Pro residues, to interfere with β-sheet formation in these β-hairpin structures 23; 48. We provided evidence that these peptides are reversible inhibitors of seeded polyQ elongation 48. For the present experiment, we fused such an inhibitor peptide, PGQ9P1,2,3, to httNT to produce a highly mutated htt N-terminal fragment analog (Table 1).

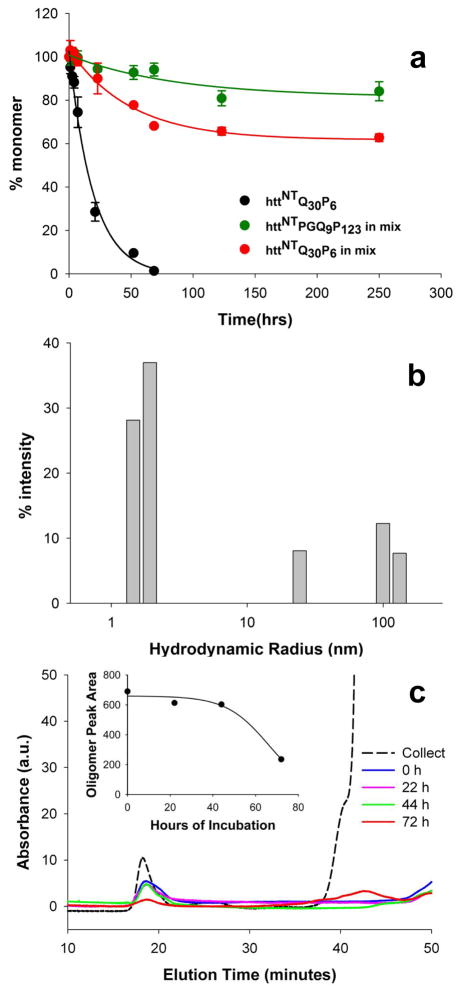

We found that a slight molar excess of this peptide with respect to httNTQ30P6K2 inhibits aggregation of this htt N-terminal fragment with far greater potency than httNT alone (compare Fig. 8a,

, to Fig. 2a, ◆). Pelletable aggregates containing up to 30% of the N-terminal fragments are formed within 50 hrs, but then no further aggregation takes place in this time frame. This transpires in parallel with the incorporation of about 20% of the inhibitor peptide httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 over the same time frame (Fig. 8a,

, to Fig. 2a, ◆). Pelletable aggregates containing up to 30% of the N-terminal fragments are formed within 50 hrs, but then no further aggregation takes place in this time frame. This transpires in parallel with the incorporation of about 20% of the inhibitor peptide httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 over the same time frame (Fig. 8a,

). Electron micrographs show that the aggregates produced in this co-incubation are almost entirely oligomeric even after 120 hrs (Fig. 4p).

). Electron micrographs show that the aggregates produced in this co-incubation are almost entirely oligomeric even after 120 hrs (Fig. 4p).

Figure 8.

Properties of httNTPGQ9P1,2,3. (a) inhibition httNTQ30P6K2 aggregation by equimolar httNTPGQ9P1,2,3; (b) DLS of httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 incubated alone for three hrs; (c) SEC analysis of oligomer assembly and disassembly of httNTPGQ9P1,2,3. 300 μM peptide was incubated for 24 hrs, then separated by SEC in PBS running buffer (dashed line). The oligomer peak (~18 mins) was collected and incubated at 37°C, then analyzed at the times shown. Between 44 and 72 hrs a substantial portion of oligomer (~18 mins) dissociates to monomer (~42 mins).

HttNTPGQ9P1,2,3 incubated alone generates very little pelletable aggregate in kinetics analysis (not shown), and only monomer and small aggregates in a dynamic light scattering (DLS) analysis at 3 hrs (Fig. 8b). Incubation of this peptide in isolation for 120 hrs shows a uniform population of regular oligomeric aggregates in the 10–30 nm range by EM (Fig. 4o), in good agreement with the 3 hr DLS measurement. Incubation of this peptide for 24 hrs followed by SEC gives two major peaks, one at the void (>700 KDa) corresponding to well-behaved aggregates and one at ~ 14 KDa, corresponding to the monomer (Fig. 8c). Collection of the void peak followed by incubation at 37 °C showed that this oligomeric fraction is moderately stable, not decaying for the first 24 hrs but diminishing after 72 hrs with concomitant regeneration of monomer (Fig. 8c inset). These data suggest that httNT fused to PGQ9P1,2,3 produces a molecule that is about as capable of making oligomers as are polyQ-containing htt N-terminal fragments of similar size 32, but which, in contrast to the unbroken polyQ versions, cannot progress to make amyloid fibrils. Interestingly, these isolated oligomers dissociate to monomer only slightly more slowly than the dissociation of isolated httNTQ8K2 oligomers (M. Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted), consistent with a dominant role of httNT packing in determining oligomer stability.

Intrinsic fluorescence confirms the compatibility of the httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 molecule with regular oligomer structure. Fluorescence of isolated aggregates from an incubated mixture of httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 (F17W) and httNTQ30P6K2 (Fig. 5a, orange) yields a strong fluorescence spectrum (confirming the presence of the Pro-rich analog in the aggregates) with an emission maximum identical to that of homogeneous httNTQ30P6K2 (F17W) oligomers (Fig. 5a, green). This suggests that, in contrast to simple httNT inhibitors, httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 inhibitors co-assemble with httNTQ30P6K2 peptides as a true structural analog of httNTQ30P6K2.

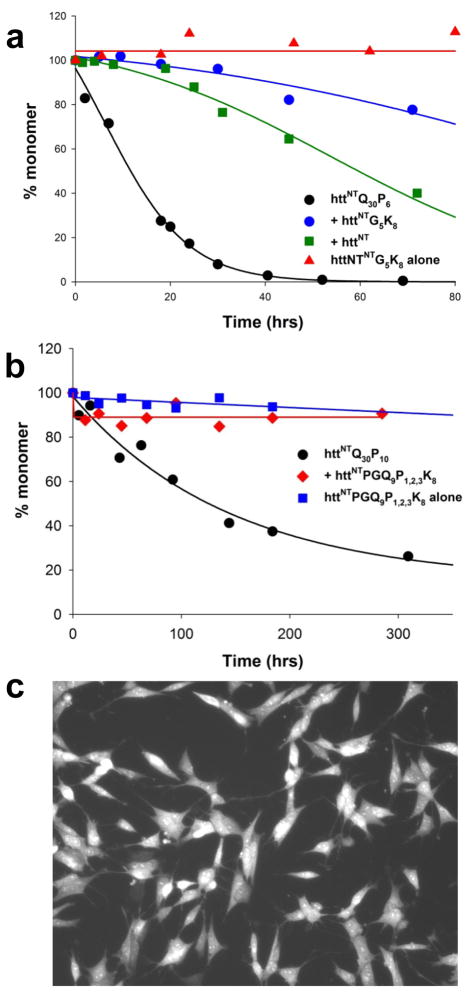

Cell-penetrating versions of oligomer-targeted inhibitors

The ability of httNT and derivatives to slow or block nucleation of amyloid structure within oligomeric intermediates of htt N-terminal fragments suggests possible therapeutic applications. One means to deliver peptides into cells is by fusion to cell-penetrating peptide (CPP) sequences 49. We designed inhibitors in which the CPP sequence is placed on the C-terminus of the inhibitors, and chose as a CPP the artificial Lys8 sequence 50, since Lys8 merely extends the Lys2 moiety we typically add to our peptides to improve kinetic solubility 51 (Table 1). In the case of the httNT peptide, we also incorporated a Gly5 spacer. We thus tested C-terminal Lys8 extensions of both httNT (Fig. 9a) and httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 (Fig. 9b). The results show that the inhibitory activity of the httNT-based molecules is not negatively affected by the C-terminal Lys8 extension, and, at least in the case of httNT itself, appears to be somewhat improved by it (Fig. 9a). We also confirmed the ability of one of these peptides to readily enter mammalian cells by obtaining a Cys analog, httNTG4CK8, modifying it with Alexa633 (Methods), and adding the purified peptide to SHSY5Y cells in culture. After 10 mins incubation, followed by cell washes, the cells exhibited a strong fluorescence indicating cell-penetrance (Fig. 9c). As previously found for other cell penetrating peptides, cell uptake was improved, and cytoplasmic localization facilitated, with the inclusion of 1-pyrenebutyric acid in the medium 52.

Figure 9.

Properties of cell penetrating peptide versions of inhibitors. (a) Inhibition of httNTQ30P6K2 aggregation by httNTG5K8 and controls; (b) Inhibition of httNTQ30P10K2 aggregation by httNT PGQ9P1,2,3 K8 and controls; c) Cytosolic delivery of httNTG4CK8-Alexa633 into SHSY5Y cells (Methods). After 10 mins exposure to peptide plus 1-pyrenebutyric acid, cells were washed extensively with PBS and imaged.

DISCUSSION

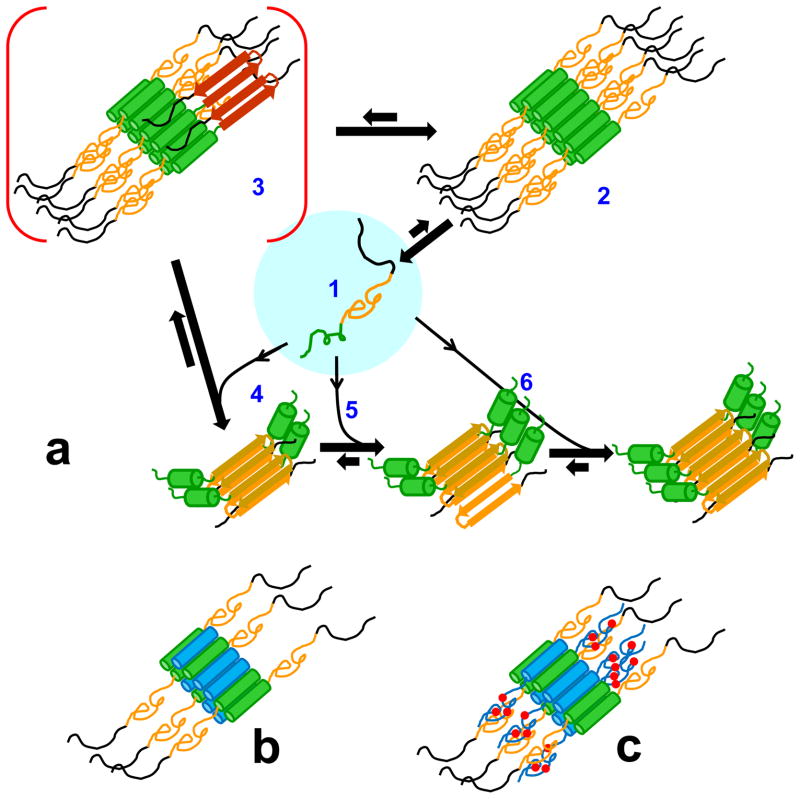

The precise role of early, non-amyloid, oligomeric intermediates in amyloid assembly has long been debated. In different amyloid systems, evidence has been presented for their being either on-pathway 53; 54 or off-pathway 55; 56. In the case of polyQ-containing htt N-terminal fragments, we have made a case for the initial α-helix rich oligomers being both on-pathway and off-pathway (Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted). These roles are reflected in the current working model Fig. 10a).

Figure 10.

α-Helix rich molecules in htt N-terminal fragment aggregation and its inhibition. (a) A model for nucleated growth in htt N-terminal fragment aggregation (modified from Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted). When the htt N-terminal fragment monomer (a1: httNT, green; polyQ, orange; Pro-rich domain, black) assembles into the oligomeric intermediate (a2), the httNT segment takes on α-helix structure whose packing with other httNT segments into a helical bundle stabilizes the oligomer. As a consequence, the disordered polyQ chains are brought together closely in space within the oligomer, which lowers the barrier to formation of nuclei with amyloid structural elements (a3, polyQ extended chain, red). Monomers present at this stage facilitate elongation into growing amyloid fibrils (a4, a5, a6). In the final stages of amyloid growth, as the monomer pool is depleted, oligomers that have not undergone nucleation dissociate (a2 -> a1) to generate more monomers to support fibril elongation. (b) structural model for the inhibition complex (oligomer) between httNT (blue cylinders) and an htt N-terminal fragment; (c) structural model for the inhibition complex between an htt N-terminal fragment and a C-terminally extended httNT inhibitor, such as httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 or httNTPGQ9P1,2,3K8 (blue cylinders = httNT helices; blue lines = PGQ9 sequence; red circles = additional Pro residues (see Table 1)).

Previously we reported that, for htt N-terminal fragment aggregation, a number of aggregate structural parameters, including Trp fluorescence quenching, ThT binding, polyQ accessibility, seeding capability, and fibrillar morphology all begin to change just at the time where aggregation kinetics dramatically increase 32. In more recent work (Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted), we provided evidence for an initial build-up of α-helix rich aggregates based on tetrameric building blocks in equilibrium with monomers. These early aggregates begin to accumulate β-structure in FTIR spectra contemporaneously with a fluorescence change associated with onset of amyloid formation. We interpreted these data to indicate the existence of a key structural conversion (i.e., nucleation) within the oligomer population that is required for onset of rapid fibril growth (Fig. 10a, structure 3). Since, in analogy to httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 oligomers (Fig. 8c), isolated httNTQN oligomers readily dissociate to monomers (Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted), we hypothesized that some oligomers never undergo the structural conversion of nucleation, instead serving as a reservoir for monomer release to sustain late-stage amyloid growth (M. Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted). Thus, some α-helix rich oligomers may serve an on-pathway role, and some an off-pathway role (M. Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted) (Fig. 10a). Since the httNT sequence alone undergoes a regular tetramerization and forms α-helix rich aggregates (M. Jayaraman, Ms. submitted), it is likely that self-associated α-helical httNT segments serve as the core of httNTQN oligomers. Interestingly, part of the httNT sequence remains in α-helix throughout nucleation and elongation (Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted) and is even retained in the mature amyloid fibrils as a stable, water accessible structural element 43 (Jararaman et al., Ms. submitted) (Fig. 10a).

In this paper we describe the characterization of two classes of inhibitors that interfere with the nucleation mechanism discussed above. One class of inhibitor includes molecules that are capable of co-assembling with polyQ-containing htt N-terminal fragments into mixed oligomers, resulting in a decreased local concentration of polyQ within these oligomers (Fig. 10b). The lower density of polyQ in these mixed oligomers decreases the frequency of interactions between polyQ segments and thereby reduces the effectiveness of either nucleus formation and/or nucleus elongation, and therefore the overall efficiency of nucleation. This class of inhibitors includes httNT and its short polyQ and Lys8 extensions, as well as various analogs of httNT, including all-D httNT, retro-inverso httNT, and some httNT scrambled sequences. The other class of inhibitor consists of molecules that contain an httNT segment plus a mutated polyQ sequence designed so that, within the mixed oligomer (Fig. 10c), they can directly inhibit polyQ aggregate formation and elongation. This class is represented in this paper by the peptides httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 and httNTPGQ9P1,2,3K8. A number of small molecules have been identified that are capable of slowing huntingtin N-terminal fragment amyloid formation in vitro. One compound, (−)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), was shown to lead to increased the sizes of oligomeric intermediates in the process of reducing amyloid formation 57. Although details may be substantially different, it is interesting that enlarged oligomers accumulate in reactions inhibited by both httNT-related peptides and EGCG.

These httNT-related inhibitor peptides may have therapeutic applications, depending on the structural nature of the HD toxic species. Thus, if some form of mature amyloid aggregate is responsible for HD pathology, then peptides that inhibit the nucleation of amyloid structure should be protective. While delivery and stability of peptide drugs is always an issue, we show here that the inhibitory activity of httNT is maintained when the peptide is synthesized from D amino acids (expected to stabilize the peptide against proteases), and inhibitory activity is actually enhanced when the cell-penetrating peptide sequence Lys8 is appended to httNT. On the other hand, if the toxic species is an oligomer 10, then the inhibitors described in this paper might be counterproductive, since they actually function by stimulating the formation of mixed oligomers with extended lifetimes and restricted abilities to mature into amyloid. Interestingly, a molecule similar to httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 has already been tested in a cell model. Subsequent to our reports of the aggregation properties of Pro-Gly interrupted polyQ molecules 23; 48, Poirier et al. expressed htt exon1 analogs containing very similar hypermutated polyQ sequences, including one resembling httNTPGQ9P1,2,3, in cultured cells and primary cortical neurons. Cells producing these proline/glycine polyQ mutants exhibited only minor levels of both visible aggregates and cytotoxicity 58. Our characterization in this paper of the aggregation properties of httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 suggests that the protein expressed in the Poirier et al. experiments, while limiting the amount of accumulated amyloid, may have produced significant amounts of oligomers, such as those shown in Figure 3o. Considering the Poirier et al. 58 report in the context of the results described here, the simplest interpretation is that oligomers of htt N-terminal fragments are not toxic. However, it is possible that the hypermutated polyQ, while not diminishing oligomer formation, somehow diminishes oligomer toxicity (in ways other than by inhibiting amyloid formation). Based on our results, it would now be interesting to investigate cell models co-expressing a normal expanded polyQ htt N-terminal fragment along with an httNTPGQ9P1,2,3-like inhibitor.

Regardless of their prospects as therapeutics, the molecules described here are important in helping to validate the mechanism for htt N-terminal fragment aggregation nucleation (Fig. 10a) as well as support a recent, general model for amyloid formation by disordered peptides like Aβ and islet amyloid polypeptide 59. In their step-wise model, Abendini and Raleigh propose initial formation of oligomeric intermediates composed of peptides in which one segment is bundled into α-helix rich cores while another segment is left disordered. In a following step, the highly concentrated disordered segments interact to initiate amyloid structure formation. In their model, the initial α-helical segment later reshapes to become incorporated into the amyloid β-sheet. In contrast, in the case of htt fragments, the httNT segment appears to remain in α-helix in the mature amyloid fibril product 43(Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted). In this paper, we provide further support for this general mechanism by demonstrating the efficacy of inhibitor molecules designed to co-assemble into mixed α-helical oligomers.

For example, httNT and a variety of analogs appear to inhibit amyloid nucleation by efficiently co-assembling with htt N-terminal fragments into mixed oligomers. This leads to a reduction in the local concentration of polyQ elements on the surface of the oligomers, which reduces their ability to interact to form β-sheet rich nuclei for amyloid formation. Although a similar mechanism may be at work in the ability of C-terminal fragments of the Aβ molecule to make mixed oligomers with full length Aβ and to inhibit Aβ toxicity 60, detailed studies have not revealed any correlation of inhibitory activity with the ability to make α-helical oligomers 61; 62.

In this paper we also describe how httNT derivatives with an attached inhibitor of polyQ elongation, like httNTPGQ9P1,2,3, are particularly strong inhibitors of nucleation of amyloid structure in htt N-terminal fragments. These inhibitors most likely act by co-assembling with htt N-terminal fragments to make oligomers in which nucleation by surface-exposed polyQ elements is actively inhibited by the ability of the PGQ9P1,2,3 element to interfere with polyQ amyloid formation. This makes this class of inhibitor conceptually identical to a recently described inhibitor of IAPP amyloid formation 59; 63. In that case, one or more proline residues were inserted into a portion of IAPP that did not disrupt its ability to make oligomers or co-oligomers, but did interfere with nucleation of amyloid formation 59; 63.

The structural details by which α-helix rich oligomers are held together remain to be elucidated. Feasible models for tetramer structure include parallel and anti-parallel helical bundles, as well as hemoglobin type folds in which α-helices are more orthogonally packed. Tetramers might assemble further into sedimentable oligomers either through the httNT segments, the polyQ segments, or both. However, since httNT alone forms tetramers, regular higher multimers, and sedimentable α-helical oligomers (M. Jayaraman et al., Ms. submitted), and since, as shown here, httNT itself co-assembles with httNTQN sequences and effectively inhibits amyloid nucleation, the simplest model consistent with the accumulated experimental data requires only httNT contacts for oligomer formation.

Besides these implications for the specificity of mixed oligomer formation, the scrambled peptide results make an additional point. The fact that a collection of scrambled sequences exhibits three different behaviors, i.e. (a) no effect, (b) amyloid formation, and (c) nucleation inhibition, points out the limitations of the common practice of constructing only a single scrambled sequence control as a test for specificity in the behavior of a bioactive peptide.

METHODS

Materials and general methods

Synthetic peptides were obtained crude and purified by reverse phase HPLC and confirmed by mass spectrometry as described previously 64. Most peptides were from the Keck Biotechnology Center at Yale University; the scrambled httNT sequences were commissioned from GenScript, Inc. and Sigma, Inc. Acetonitrile, hexafluoroisopropanol (99.5%, spectrophotometric grade), and formic acid were from Acros Organics, and trifluoroacetic acid (99.5%, Sequanal Grade) from Pierce. Most peptides were disaggregated using a 1:1 mixture of HFIP and TFA, as described 64. The exceptions are the random sequences listed in Table 2, which were available in too low an amount for our normal disaggregation protocol. The scrambled sequence peptides were dissolved in pH 3 water and centrifuged at 386,000 g for two hrs in a table top ultracentrifuge to remove any aggregates. HttNT gave identical inhibition whether disaggregated by centrifugation only or by our standard TFA/HFIP protocol. Aggregation rates were determined by a sedimentation assay in which aliquots of ongoing reaction mixtures were centrifuged, and the amount of monomer remaining determined by analytical reverse phase HPLC of the supernatant 64. Some peptides contained a Phe17->Trp replacement in order to use Trp fluorescence to gauge the residue’s solvent accessibility in aggregates. This replacement was previously shown to have only a very small effect, at best, on aggregation kinetics 32. The isolation of aggregates for seeding and fluorescence analysis was conducted by centrifuging a reaction aliquot at 20817 × g in an Eppendorf centrifuge at 4 ° C for 30 mins, washing the pellet 2–3 times with PBS, resuspending in buffer, and determining the aggregate concentration by an HPLC analysis of a formic acid dissolved aliquot, as described 64. Intrinsic tryptophan fluorescence of isolated aggregates was determined as described 65. DLS was performed on a Wyatt Dynapro microplate system using the built in software. Scrambled sequences were generated by using the randperm function in MATLAB. The input consisted of the wild type httNTQ sequence and the required number of scrambled versions was set at 50. The inbuilt randperm function was then used to rearrange the sequence randomly and generate 50 permutations. Theoretical helical propensities were calculated using the AGADIR program online (http://agadir.crg.es/). The conditions used for the calculations were pH 7.4, 298K and 0.1 ionic strength. Hydrophobic moments 47 were calculated by assuming entirely α-helical structure and analyzing the sequence using the Analysis module of the Heliquest program (http://heliquest.ipmc.cns.fr) with a window size of 18.

Electron microscopy

Aliquots of aggregation reaction mixtures were taken at different time points and visualized by electron microscopy. A 3 μl sample was placed on a freshly glow-discharged carbon-coated grid, allowed to adsorb for 2 minutes, and washed with deionized water before staining with 2 μl of 1% uranyl acetate and blotting. Grids were imaged on a Tecnai T12 microscope (FEI Co., Hillsboro, Oregon) operating at 120kV and 30,000x magnification, and equipped with an UltraScan 1000 CCD camera (Gatan, Pleasanton, California) with post-column magnification of 1.4x.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR)

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy of various samples was performed using MB series spectrophotometer with PROTA software (ABB Bomem). Protein aggregates were harvested by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm and the pellet was washed 3 times with PBS. Spectra of re-suspended aggregates were recorded at 4 cm−1 resolution (400 scans at room temperature). Spectra were corrected for the residual buffer absorption by subtracting the buffer alone spectrum interactively until a flat baseline was obtained between 1700–1800 cm-1. Second-derivative spectra for the Amide I region were calculated from the primary spectrum by using PROTA software.

Circular dichroism spectroscopy and spectral analysis

Far-UV CD measurements were performed on a JASCO J-810 spectropolarimeter using a 0.1 cm path length cuvette. Peptide samples were prepared by dissolving pure peptide in acidic water (pH 3) and centrifuging at 435,680 × g for 2 hrs, using the top 50% of the supernatant as the stock solution. All samples were prepared in 10mM Tris, pH 7.4 at concentrations between 76 μM −150 μM. Far-UV CD spectra were collected at 1nm resolution with a scan rate of 100nm/min and averaged over four scans and corrected for the buffer signal. % helicity values were calculated using the CONTINLL program in the CDPRO package with the SP37A (ibasis 5) reference set.

Test for low molecular weight complex formation

A mixture of 28.9 μM httNTQ30P6K2 (F17W) and 34.5 μM httNT in 10 mM sodium phosphate, 150 mM NaCl with 0.05% sodium azide, pH 7.4, was incubated at 37 °C for 3 hrs, then centrifuged (5000 rpm) and 200 μL of the supernatant injected onto a Superdex 75 10/200 column (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) equilibrated in the same buffer. 500 μL portions of the peak fractions were then analyzed on a reverse phase HPLC column on an Agilent 1100 LC-MS system.

Fluorescence labeling of cell penetrating peptide

Purified httNTG4CK8 was disaggregated 64 and the resulting dried film (~1.5mg) was resuspended in 1ml of deoxygenated labeling buffer (20mM HEPES pH 8.2, 5mM EDTA, 25mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP; Pierce, Inc.)). The peptide solution was centrifuged 1 hr at 100,000 g and the concentration was checked by HPLC. A 5:1 molar excess of Alexa Fluor® 633 C5-maleimide (Invitrogen/Molecular Probes) was dissolved in 50 μl of labeling buffer and added drop-wise to the peptide solution. The labeling reaction, incubated with constant stirring at 23 °C, was ~50% complete after 1 hr, and complete after overnight reaction, by analytical HPLC. Peptide components were separated from buffer and excess labeling reagent on a D-Salt™ Polyacrylamide Desalting Column (Pierce) equilibrated in 20mM HEPES pH 8.2, 5mM EDTA buffer. Fractions (0.5 ml) were collected and checked by HPLC-mass spectrometry to confirm the identity and purity of the Alexa labeled peptide. Peptide fractions were pooled and aliquots containing desired amounts of peptide were lyophilized and stored at −80 °C.

Cell uptake of fluorescent cell penetrating peptide

SHSY5Y neuroblastoma cells were seeded at 5 × 105 cells per well in a 96 wells plate and cultured for 24hr in complete growth medium (DMEM (Cellgro) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (HyClone), 2 mM L-glutamine (GIBCO) and Penicillin-Streptomycin (HyClone)). A frozen sample of the labeled inhibitor peptide (see above) was disaggregated overnight in TFA-HFIP and the solvents were evaporated under a stream of argon. The peptide film was further dried under vacuum for 1 hour and resuspended in PBS 64. The peptide concentration of the PBS solution was calculated from the absorbance at 633nm using the extinction coefficient reported by the manufacturer. Prior to the experiment, cells were washed with warm PBS and incubated with 50 μl of 100 μM 1-pyrenebutyric acid (Sigma) in PBS for 5 mins at 37°C after which 50 μl of 10 μM inhibitor peptide was added to achieve a final concentration of 5 μM. After 10 minutes of incubation at 37°C, cells were washed four times with warm PBS and imaged using an Olympus IX71 inverted fluorescent microscope equipped with a cy5 filter.

Curve fitting

The aggregation kinetics of all the control substrate reactions were fit to a three-parameter exponential decay function in keeping with our current understanding of the aggregation of these peptides. Similarly, the aggregation kinetics of the substrates in the presence of the httNT and its analogs were fitted with a three parameter sigmoidal function in order to describe the lag-phase that is observed in such inhibition. On the other hand, in the inhibition reaction with the httNTPGQ9P1,2,3 inhibitor, in which the only detectible aggregate formed is an apparently stable population of mixed oligomers, the aggregation kinetics of the substrate were fit to a three-parameter exponential. It should be noted that curve fits have been conducted here both to visually organize the data to improve accessibility, and to allow objective estimation of t½ times of aggregation, but not to support any particular mechanistic hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge funding support from NIH R01 AG019322. EMs were collected in the Structural Biology Department’s EM facility administered by Drs. James Conway and Alexander Makhov. We thank S.J.A Prakash for help with the random sequence generator.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Zuccato C, Valenza M, Cattaneo E. Molecular mechanisms and potential therapeutical targets in Huntington’s disease. Physiol Rev. 2010;90:905–81. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00041.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wilburn B, Rudnicki DD, Zhao J, Weitz TM, Cheng Y, Gu XF, Greiner E, Park CS, Wang N, Sopher BL, La Spada AR, Osmand A, Margolis RL, Sun YE, Yang XW. An antisense CAG repeat transcript at JPH3 locus mediates expanded polyglutamine protein toxicity in Huntington’s disease-like 2 mice. Neuron. 2011;70:427–440. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.03.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bates GP, Benn C. The polyglutamine diseases. In: Bates GP, Harper PS, Jones L, editors. Huntington’s Disease. Oxford University Press; Oxford, U.K: 2002. pp. 429–472. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sathasivam K, Lane A, Legleiter J, Warley A, Woodman B, Finkbeiner S, Paganetti P, Muchowski PJ, Wilson S, Bates GP. Identical oligomeric and fibrillar structures captured from the brains of R6/2 and knock-in mouse models of Huntington’s disease. Human Molecular Genetics. 2010;19:65–78. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddp467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scherzinger E, Sittler A, Schweiger K, Heiser V, Lurz R, Hasenbank R, Bates GP, Lehrach H, Wanker EE. Self-assembly of polyglutamine-containing huntingtin fragments into amyloid-like fibrils: implications for Huntington’s disease pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:4604–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen S, Berthelier V, Yang W, Wetzel R. Polyglutamine aggregation behavior in vitro supports a recruitment mechanism of cytotoxicity. J Mol Biol. 2001;311:173–182. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morley JF, Brignull HR, Weyers JJ, Morimoto RI. The threshold for polyglutamine-expansion protein aggregation and cellular toxicity is dynamic and influenced by aging in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:10417–22. doi: 10.1073/pnas.152161099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bates G. Huntingtin aggregation and toxicity in Huntington’s disease. Lancet. 2003;361:1642–4. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13304-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Michalik A, Van Broeckhoven C. Pathogenesis of polyglutamine disorders: aggregation revisited. Hum Mol Genet. 2003;12(Suppl 2):R173–86. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddg295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross CA, Poirier MA. Opinion: What is the role of protein aggregation in neurodegeneration? Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:891–8. doi: 10.1038/nrm1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies SW, Turmaine M, Cozens BA, DiFiglia M, Sharp AH, Ross CA, Scherzinger E, Wanker EE, Mangiarini L, Bates GP. Formation of neuronal intranuclear inclusions underlies the neurological dysfunction in mice transgenic for the HD mutation. Cell. 1997;90:537–48. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80513-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wheeler VC, Gutekunst CA, Vrbanac V, Lebel LA, Schilling G, Hersch S, Friedlander RM, Gusella JF, Vonsattel JP, Borchelt DR, MacDonald ME. Early phenotypes that presage late-onset neurodegenerative disease allow testing of modifiers in Hdh CAG knock-in mice. Hum Mol Genet. 2002;11:633–40. doi: 10.1093/hmg/11.6.633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Menalled LB, Sison JD, Dragatsis I, Zeitlin S, Chesselet MF. Time course of early motor and neuropathological anomalies in a knock-in mouse model of Huntington’s disease with 140 CAG repeats. J Comp Neurol. 2003;465:11–26. doi: 10.1002/cne.10776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tanaka Y, Igarashi S, Nakamura M, Gafni J, Torcassi C, Schilling G, Crippen D, Wood JD, Sawa A, Jenkins NA, Copeland NG, Borchelt DR, Ross CA, Ellerby LM. Progressive phenotype and nuclear accumulation of an amino-terminal cleavage fragment in a transgenic mouse model with inducible expression of full-length mutant huntingtin. Neurobiol Dis. 2006;21:381–91. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2005.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gu X, Greiner ER, Mishra R, Kodali R, Osmand A, Finkbeiner S, Steffan JS, Thompson LM, Wetzel R, Yang XW. Serines 13 and 16 are critical determinants of full-length human mutant huntingtin induced disease pathogenesis in HD mice. Neuron. 2009;64:828–40. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Arrasate M, Mitra S, Schweitzer ES, Segal MR, Finkbeiner S. Inclusion body formation reduces levels of mutant huntingtin and the risk of neuronal death. Nature. 2004;431:805–10. doi: 10.1038/nature02998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Takano H, Gusella JF. The predominantly HEAT-like motif structure of huntingtin and its association and coincident nuclear entry with dorsal, an NF-kB/Rel/dorsal family transcription factor. BMC Neurosci. 2002;3:15. doi: 10.1186/1471-2202-3-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tartari M, Gissi C, Lo Sardo V, Zuccato C, Picardi E, Pesole G, Cattaneo E. Phylogenetic comparison of huntingtin homologues reveals the appearance of a primitive polyQ in sea urchin. Mol Biol Evol. 2008;25:330–8. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msm258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang CE, Tydlacka S, Orr AL, Yang SH, Graham RK, Hayden MR, Li S, Chan AW, Li XJ. Accumulation of N-terminal mutant huntingtin in mouse and monkey models implicated as a pathogenic mechanism in Huntington’s disease. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:2738–51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddn175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ratovitski T, Gucek M, Jiang H, Chighladze E, Waldron E, D’Ambola J, Hou Z, Liang Y, Poirier MA, Hirschhorn RR, Graham R, Hayden MR, Cole RN, Ross CA. Mutant huntingtin N-terminal fragments of specific size mediate aggregation and toxicity in neuronal cells. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:10855–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M804813200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tebbenkamp AT, Swing D, Tessarollo L, Borchelt DR. Premature death and neurologic abnormalities in transgenic mice expressing a mutant huntingtin exon-2 fragment. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:1633–42. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen S, Ferrone F, Wetzel R. Huntington’s Disease age-of-onset linked to polyglutamine aggregation nucleation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:11884–11889. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182276099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thakur A, Wetzel R. Mutational analysis of the structural organization of polyglutamine aggregates. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:17014–17019. doi: 10.1073/pnas.252523899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhattacharyya AM, Thakur AK, Wetzel R. polyglutamine aggregation nucleation: thermodynamics of a highly unfavorable protein folding reaction. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15400–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501651102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Slepko N, Bhattacharyya AM, Jackson GR, Steffan JS, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Wetzel R. Normal-repeat-length polyglutamine peptides accelerate aggregation nucleation and cytotoxicity of expanded polyglutamine proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:14367–72. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0602348103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jayaraman M, Kodali R, Wetzel R. The impact of ataxin-1-like histidine insertions on polyglutamine aggregation. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2009;22:469–78. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kar K, Jayaraman M, Sahoo B, Kodali R, Wetzel R. Critical nucleus size for disease-related polyglutamine aggregation is repeat-length dependent. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2011;18:328–36. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Chiara C, Menon RP, Dal Piaz F, Calder L, Pastore A. Polyglutamine is not all: the functional role of the AXH domain in the ataxin-1 protein. J Mol Biol. 2005;354:883–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2005.09.083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellisdon AM, Thomas B, Bottomley SP. The two-stage pathway of ataxin-3 fibrillogenesis involves a polyglutamine-independent step. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:16888–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M601470200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ignatova Z, Gierasch LM. Extended polyglutamine tracts cause aggregation and structural perturbation of an adjacent beta barrel protein. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:12959–67. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511523200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ignatova Z, Thakur AK, Wetzel R, Gierasch LM. In-cell aggregation of a polyglutamine-containing chimera is a multistep process initiated by the flanking sequence. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:36736–43. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M703682200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thakur AK, Jayaraman M, Mishra R, Thakur M, Chellgren VM, Byeon IJ, Anjum DH, Kodali R, Creamer TP, Conway JF, Gronenborn AM, Wetzel R. Polyglutamine disruption of the huntingtin exon 1 N terminus triggers a complex aggregation mechanism. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:380–9. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Saunders HM, Bottomley SP. Multi-domain misfolding: understanding the aggregation pathway of polyglutamine proteins. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2009;22:447–51. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Atwal RS, Xia J, Pinchev D, Taylor J, Epand RM, Truant R. Huntingtin has a membrane association signal that can modulate huntingtin aggregation, nuclear entry and toxicity. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:2600–15. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddm217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rockabrand E, Slepko N, Pantalone A, Nukala VN, Kazantsev A, Marsh JL, Sullivan PG, Steffan JS, Sensi SL, Thompson LM. The first 17 amino acids of Huntingtin modulate its sub-cellular localization, aggregation and effects on calcium homeostasis. Hum Mol Genet. 2007;16:61–77. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kelley NW, Huang X, Tam S, Spiess C, Frydman J, Pande VS. The predicted structure of the headpiece of the Huntingtin protein and its implications on Huntingtin aggregation. J Mol Biol. 2009;388:919–27. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2009.01.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mohan A, Oldfield CJ, Radivojac P, Vacic V, Cortese MS, Dunker AK, Uversky VN. Analysis of molecular recognition features (MoRFs) J Mol Biol. 2006;362:1043–59. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.07.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sugase K, Dyson HJ, Wright PE. Mechanism of coupled folding and binding of an intrinsically disordered protein. Nature. 2007;447:1021–5. doi: 10.1038/nature05858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steffan JS, Agrawal N, Pallos J, Rockabrand E, Trotman LC, Slepko N, Illes K, Lukacsovich T, Zhu YZ, Cattaneo E, Pandolfi PP, Thompson LM, Marsh JL. SUMO modification of Huntingtin and Huntington’s disease pathology. Science. 2004;304:100–4. doi: 10.1126/science.1092194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aiken CT, Steffan JS, Guerrero CM, Khashwji H, Lukacsovich T, Simmons D, Purcell JM, Menhaji K, Zhu YZ, Green K, Laferla F, Huang L, Thompson LM, Marsh JL. Phosphorylation of threonine 3: implications for Huntingtin aggregation and neurotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:29427–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.013193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thompson LM, Aiken CT, Kaltenbach LS, Agrawal N, Illes K, Khoshnan A, Martinez-Vincente M, Arrasate M, JG, OSR, Khashwji H, Lukacsovich T, Zhu YZ, Lau AL, Massey A, Hayden MR, Zeitlin SO, Finkbeiner S, Green KN, Laferla FM, Bates G, Huang L, Patterson PH, Lo DC, Cuervo AM, Marsh JL, Steffan JS. IKK phosphorylates Huntingtin and targets it for degradation by the proteasome and lysosome. J Cell Biol. 2009;187:1083–1099. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200909067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Tam S, Spiess C, Auyeung W, Joachimiak L, Chen B, Poirier MA, Frydman J. The chaperonin TRiC blocks a huntingtin sequence element that promotes the conformational switch to aggregation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2009;16:1279–85. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Sivanandam VN, Jayaraman M, Hoop CL, Kodali R, Wetzel R, van der Wel PC. The aggregation-enhancing huntingtin N-terminus is helical in amyloid fibrils. J Am Chem Soc. 2011;133:4558–66. doi: 10.1021/ja110715f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chorev M, Goodman M. A dozen years of retro-inverso peptidomimetics. Acc Chem Res. 1993;26:266–273. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Goodman M, Chorev M. On the concept of linear modified retro-peptide structures. Acc Chem Res. 1979;12:1–7. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Munoz V, Serrano L. Elucidating the folding problem of helical peptides using empirical parameters. Nat Struct Biol. 1994;1:399–409. doi: 10.1038/nsb0694-399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eisenberg D, Weiss RM, Terwilliger TC. The hydrophobic moment detects periodicity in protein hydrophobicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984;81:140–4. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.1.140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Thakur AK, Yang W, Wetzel R. Inhibition of polyglutamine aggregate cytotoxicity by a structure-based elongation inhibitor. FASEB J. 2004;18:923–925. doi: 10.1096/fj.03-1238fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wagstaff KM, Jans DA. Protein transduction: cell penetrating peptides and their therapeutic applications. Curr Med Chem. 2006;13:1371–87. doi: 10.2174/092986706776872871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tilstra J, Rehman KK, Hennon T, Plevy SE, Clemens P, Robbins PD. Protein transduction: identification, characterization and optimization. Biochem Soc Trans. 2007;35:811–5. doi: 10.1042/BST0350811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen S, Berthelier V, Hamilton JB, O’Nuallain B, Wetzel R. Amyloid-like features of polyglutamine aggregates and their assembly kinetics. Biochemistry. 2002;41:7391–9. doi: 10.1021/bi011772q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takeuchi T, Kosuge M, Tadokoro A, Sugiura Y, Nishi M, Kawata M, Sakai N, Matile S, Futaki S. Direct and rapid cytosolic delivery using cell-penetrating peptides mediated by pyrenebutyrate. ACS Chem Biol. 2006;1:299–303. doi: 10.1021/cb600127m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Harper JD, Lieber CM, Lansbury PT., Jr Atomic force microscopic imaging of seeded fibril formation and fibril branching by the Alzheimer’s disease amyloid-beta protein. Chem Biol. 1997;4:951–9. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(97)90303-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Serio TR, Cashikar AG, Kowal AS, Sawicki GJ, Moslehi JJ, Serpell L, Arnsdorf MF, Lindquist SL. Nucleated conformational conversion and the replication of conformational information by a prion determinant. Science. 2000;289:1317–21. doi: 10.1126/science.289.5483.1317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Goldsbury CS, Wirtz S, Muller SA, Sunderji S, Wicki P, Aebi U, Frey P. Studies on the in vitro assembly of a beta 1–40: implications for the search for a beta fibril formation inhibitors. J Struct Biol. 2000;130:217–31. doi: 10.1006/jsbi.2000.4259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chen YR, Glabe CG. Distinct early folding and aggregation properties of Alzheimer amyloid-beta peptides Abeta40 and Abeta42: stable trimer or tetramer formation by Abeta42. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:24414–22. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M602363200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ehrnhoefer DE, Duennwald M, Markovic P, Wacker JL, Engemann S, Roark M, Legleiter J, Marsh JL, Thompson LM, Lindquist S, Muchowski PJ, Wanker EE. Green tea (−)-epigallocatechin-gallate modulates early events in huntingtin misfolding and reduces toxicity in Huntington’s disease models. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:2743–51. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddl210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Poirier MA, Jiang H, Ross CA. A structure-based analysis of huntingtin mutant polyglutamine aggregation and toxicity: evidence for a compact beta-sheet structure. Hum Mol Genet. 2005;14:765–74. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Abedini A, Raleigh DP. A critical assessment of the role of helical intermediates in amyloid formation by natively unfolded proteins and polypeptides. Protein Eng Des Sel. 2009;22:453–9. doi: 10.1093/protein/gzp036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fradinger EA, Monien BH, Urbanc B, Lomakin A, Tan M, Li H, Spring SM, Condron MM, Cruz L, Xie CW, Benedek GB, Bitan G. C-terminal peptides coassemble into Abeta42 oligomers and protect neurons against Abeta42-induced neurotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:14175–80. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0807163105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Li H, Monien BH, Fradinger EA, Urbanc B, Bitan G. Biophysical characterization of Abeta42 C-terminal fragments: inhibitors of Abeta42 neurotoxicity. Biochemistry. 2010;49:1259–67. doi: 10.1021/bi902075h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Li H, Monien BH, Lomakin A, Zemel R, Fradinger EA, Tan M, Spring SM, Urbanc B, Xie CW, Benedek GB, Bitan G. Mechanistic investigation of the inhibition of Abeta42 assembly and neurotoxicity by Abeta42 C-terminal fragments. Biochemistry. 2010;49:6358–64. doi: 10.1021/bi100773g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Abedini A, Meng F, Raleigh DP. A single-point mutation converts the highly amyloidogenic human islet amyloid polypeptide into a potent fibrillization inhibitor. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:11300–1. doi: 10.1021/ja072157y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.O’Nuallain B, Thakur AK, Williams AD, Bhattacharyya AM, Chen S, Thiagarajan G, Wetzel R. Kinetics and thermodynamics of amyloid assembly using a high-performance liquid chromatography-based sedimentation assay. Methods Enzymol. 2006;413:34–74. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(06)13003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]