Abstract

Objective

MAPK kinases MKK3 and MKK6 regulate p38 MAPK activation in inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis. Previous studies demonstrated that MKK3- or MKK6-deficiency inhibits K/BxN serum-induced arthritis. However, the role of these kinases in adaptive immunity-dependent models of chronic arthritis is not known. The goal of this study was to evaluate MKK3- and MKK6-deficiency in the collagen induced arthritis model.

Methods

Wildtype, MKK3−/−, and MKK6−/− mice were immunized with bovine type II collagen (CII). Disease activity was evaluated by semiquantitative scoring, histology, and microcomputed tomography. Serum anti-collagen antibody levels were quantified by ELISA. In-vitro T cell cytokine response was measured by flow cytometry and multiplex analysis. Expression of joint cytokines and matrix metalloproteinase was determined by qPCR.

Results

MKK6-deficiency markedly reduced arthritis severity compared with WT mice, while absence of MKK3 had an intermediate effect. Joint damage was minimal in arthritic MKK6−/− mice and intermediate in MKK3−/− mice compared with wild type mice. MKK6−/− mice had modestly lower levels of pathogenic anti-collagen antibodies than WT or MKK3−/− mice. In vitro T cell assays showed reduced proliferation and IL-17 production by MKK6−/− cells in response to type II collagen. Gene expression of synovial IL-6, matrix metalloproteinases MMP3, and MMP13 was significantly inhibited in MKK6-deficient mice.

Conclusion

Reduced disease severity in MKK6−/− mice correlated with decreased anti-collagen responses indicating that MKK6 is a crucial regulator of inflammation joint destruction in CIA. MKK6 is a potential therapeutic target in complex diseases involving adaptive immune responses like rheumatoid arthritis.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease characterized by synovial hyperplasia and joint destruction (1). The cellular processes that contribute to RA pathogenesis are regulated by 3 families of MAPKs, namely, ERK, JNK and p38 (2, 3). Of these kinases, p38 is a key regulator of pro-inflammatory cytokines (4), and inhibitors of p38 activity are effective in animal models of arthritis (5, 6). However, the same compounds are minimally effective in RA despite increased activation of the p38 pathway in rheumatoid synovium (7). Although the reasons for this paradox are unclear, several explanations have been proposed (8). Recent studies show that exposure to p38 inhibitors can decrease expression of anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10 and enhance pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-6 (9). The clinical success of compounds that inhibit proximal pathways, such as spleen tyrosine kinase (Syk) and Janus kinases (JAK), suggest that targeting upstream kinases might be more effective in RA therapy (10, 11).

A possible alternative to direct p38 inhibition is to target its upstream regulators, such as MAPK kinases MKK3 or MKK6, which phosphorylate p38 in response to cellular stress and cytokines (12). Although both kinases can activate p38, their relative contributions to inflammation vary substantially depending on cell type and stimulus. For instance, MKK3 and MKK6 are essential for TNF-stimulated p38 activation in vivo (13), while only MKK3 is required for TNF-mediated IL-6 production in murine embryonic fibroblasts (14). This signaling diversity provides an opportunity to target either kinase to inhibit inflammatory processes while limiting the effect on host defense.

Previous studies showed that MKK3 and MKK6 are activated in RA synovium and that they regulate metalloproteinase and pro-inflammatory cytokine production in cultured synoviocytes (15, 16). Either MKK3 or MKK6-deficiency reduces clinical severity and cytokine production in a passive model of arthritis, albeit through different mechanisms (17, 18). For instance, p38 phosphorylation is nearly abolished in MKK3-deficient mice, while normal p38 activation is observed in MKK6−/− mice. While these studies demonstrated the role of MKK3 and MKK6 in a model strictly dependent on innate immunity, there is no information in chronic arthritis models that require adaptive immune responses. Therefore, we assessed the function of MKK3 and MKK6 in murine collagen-induced arthritis (CIA) model. The data indicate that targeting MKK6, in particular, could be effective in diseases involving adaptive immunity.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Mice and synoviocytes

WT DBA/1 mice (6 weeks old) were purchased from Harlan Laboratories (Placentia, CA). MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice on C57/B6 background were originally obtained from Dr. Richard Flavell, Yale University. These mice were backcrossed onto DBA/1 background for 8 generations. DBA/1 background was confirmed through marker-assisted accelerated backcrossing (MAX-BAX, Charles River Laboratories, Wilmington, MA). All experimental protocols involving animals were reviewed and approved by the UCSD Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) (La Jolla, CA). Synoviocytes isolated from WT, MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice were cultured as described previously (19).

Induction and evaluation of collagen-induced arthritis (CIA)

Mice (6–8 weeks old) were immunized with bovine type II collagen in complete Freund’s adjuvant (Chondrex, Redmond, WA) as described previously (20). Ankle widths and scores were measured once weekly from day 0 to day 28, at which point measurements were made every other day. Mice were euthanized on day 35 or day 40. Clinical symptoms of arthritis were evaluated visually for each paw using a semiquantitative scoring system graded on a scale of 0–4 per paw, where 0 = no erythema or swelling, 1= erythema and mild swelling confined to the midfoot or ankle joint, 2 = mild swelling extending from ankle to midfoot, 3 = moderate swelling extending from ankle to metatarsal joints, 4 = severe swelling in the ankle, foot and digits (21). The clinical score for each mouse was the sum of the 4 paw scores for a maximum score of 16.

Microcomputed tomographical (Micro-CT) analyses

Ankle joints of naïve and arthritic WT, MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice were imaged on day 42 using Skyscan 1076 microCT-40 system (Kontich, Belgium). Samples were immersed in PBS and scanned at 9μm voxel size, applying 70 kVp, 141μA, and 1750ms exposure time, using a 1mm aluminum filter. Resulting images were filtered during reconstruction using a ring correction factor of 4, smoothing of 1 and 40% beam hardening correction. Skyscan software (Dataviewer, CTAn and CTVox) was used to reorient and analyze samples in different planes. The images were then evaluated using a semi-quantitative visual scoring scale of 0–4 for calcaneus erosion, midfoot osteopenia, midfoot erosion, midfoot cartilage damage, metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint osteopenia, MTP erosion, and MTP cartilage damage, for a maximum score of 28 for each mouse. Trabecular bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV) and cortical bone area/total area (BA/TA) values were determined using Skyscan software and represented as percent average±SEM.

Gene and protein expression in arthritic mice joints

Ankles were frozen, pulverized and RNA was isolated using Rneasy® Lipid Tissue kit per manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen, Valencia, CA). Cytokine expression was measured by quantitative real-time PCR using the GeneAmp 7300 sequence detection system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) as previously described (22). The threshold cycle (Ct) values were normalized to hypoxanthine-guanine phosphoribosyl transferase (HPRT) expression. Ankle joints from WT, MKK3−/−, and MKK6−/− arthritic mice (day 40) were snap-frozen, pulverized, and protein was extracted using modified radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM HEPES (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 10% glycerol, 2.5 mM MgCl2, 1.0 mM EDTA (pH 8.0), 20 mM β-glycerophosphate, 10 mM NaF, 1 mM Na2VO4, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μM pepstatin A, 1 mM PMSF) (23). Whole tissue lysates were fractionated by Tris-glycine buffered 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to nitrocellulose membranes followed by incubation with antibody to P-p38, p38, P-STAT3, STAT3 and actin overnight at 4°C. After washing, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibody for 2 hour at room temperature. Immunoreactive protein was detected with Immun-Star WesternC Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) using VersaDoc MP4000 imaging system (Bio-Rad). The densitometry analysis was performed using Quantity One 1-D analysis software (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Serum analytes

Serum was collected on day 40 and levels of anti-type II collagen antibodies (total IgG, IgG1 and IgG2a) were measured using ELISA kits purchased from Chondrex (Redmond, WA). Serum cytokines were quantified using multiplex bead-based Luminex assays (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA).

Lymphocyte cell proliferation and cytokine analysis

Ten days after one bovine CII injection, lymph nodes from arthritic WT, MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice were removed. The cells were isolated, counted, and resuspended in RPMI medium supplemented with 10% horse serum, HEPES, sodium pyruvate, β-mercaptoethanol, penicillin, streptomycin, glutamine and gentamicin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA). The cells (5×105/well) were treated with 50 μg/ml CB11 fragment of CNBr cleaved collagen II for 72h (Chondrex, Redmond, WA). The culture supernatants were collected and IL-17 levels were quantified by multiplex bead assays (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). For proliferation assays, 3H-thymidine was added after 72h for 24h, when the cells were harvested and analyzed using a scintillation counter. The data are represented as mean cpm ±SEM.

Statistical analysis

Data are expressed as mean±SEM. Arthritis scores of WT, MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice were analyzed using the Kruskal-Wallis test and Dunn’s multiple comparison post-hoc test. Comparisons between WT, MKK3−/− and MKK6−/−gene expression were analyzed by one-way ANOVA and Dunnett’s multiple comparison post-hoc test. Comparisons between WT and MKK6−/− groups were analyzed by two-tailed Student’s t-test. In all tests, p value <0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Effect of MKK3- and MKK6-deficiency on collagen-induced arthritis (CIA)

We previously demonstrated that the severity of K/BxN passive arthritis is markedly lower in MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice compared with WT (18). In this study, we evaluated mice deficient in MKK3 or MKK6 in the CIA model to determine the contribution of MKKs to adaptive immunity-mediated arthritis. Figure 1A shows that MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice have significantly lower arthritis scores than WT mice throughout the course of disease. Arthritis severity in the MKK6−/− group was significantly lower than MKK3−/− mice on and after day 38, suggesting that MKK6 might be more important than MKK3 in CIA.

Figure 1.

Inhibition of CIA in MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice. (A) WT (n=38), MKK3−/− (n=30), and MKK6−/− (n=25) mice were immunized with bovine CII collagen as described in Materials and Methods. Disease severity was scored by visual inspection on a scale of 0–4/paw at various times. The data are represented as average ± SEM. Arthritis scores were significantly lower at peak disease in MKK6−/− and MKK3−/− mice compared with WT (Kruskal-Wallis, p<0.001; Dunn’s multiple comparison test - WT vs. MKK6−/− p<0.005, WT vs. MKK3−/− p<0.01. Clinical scores of MKK6−/− mice were significantly lower than MKK3−/− mice after day 38 (p<0.05, n≥26/group). (B) Visualization and quantification of CIA-induced joint damage by micro-CT imaging. Representative images of naive, arthritic WT, MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice hind paw were scored on a scale of 0–4 for 7 criteria for a maximum score of 28. Data are represented as average±SEM. WT arthritic mice had significantly higher bone erosion and cartilage damage compared with MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice on day 40 (n=4/arthritic group, *p<0.03, Mann-Whitney).

Analysis of cartilage and bone damage in CIA

We then evaluated cartilage loss and bone erosion in naïve and arthritic mice using microcomputer tomography (micro-CT) at day 40 (Figure 1B). MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− arthritic mice had significantly lower cartilage loss and bone erosion (percent decrease MKK3−/−: 65% and MKK6−/−: 85%) compared with WT mice. Three-dimensional reconstruction of the calcaneus showed significantly decreased trabecular bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV) in arthritic WT mice compared with MKK6−/− mice (Figure 2A). Arthritic MKK3−/− animals showed a modest preservation of bone volume compared with WT mice. The cortical bone area/total area (BA/TA) was elevated in naïve MKK−/− compared with naïve WT mice (Figure 2B). Arthritic WT cortical BA/TA was significantly reduced compared with the MKK6−/− group. Together, these data show that either MKK3 or MKK6 deficiency protected the extracellular matrix in CIA with a rank order that was similar to the clinical effects.

Figure 2.

Visualization and quantification of CIA-induced bone erosion by micro-CT imaging. (A) Three-dimensional reconstructions of calcaneus trabecular bone volume. Percent bone volume/tissue volume (BV/TV) is shown for each group as average ± SEM. Arthritic WT mice had significantly lower trabecular percent BV/TV compared with MKK6−/− mice (n=7/arthritic group, n=2/naïve group), *p<0.02, t-test. (B) Cortical bone area in representative naive, arthritic WT, MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice. Percent cortical BA/TA was significantly lower in arthritic WT compared to MKK6−/− mice (n=7/arthritic group, n=2/naïve group, *p<0.02, t-test).

Cytokine expression in arthritic MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice

In the K/BxN model, MKK3 and MKK6 regulated synovial gene expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines and MMPs (18). In CIA, IL-6 gene expression was significantly reduced in both MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− arthritic joints compared with WT (Figure 3A). A similar pattern was observed in serum IL-6 levels in the arthritic mice (Figure 3B). MMP3 and MMP13 expression was also significantly reduced in MKK6−/− joints (Figure 3C). IL-17 gene expression was not detected in the arthritic joints of all three groups. Interestingly, TNFα and IL-1β gene expression in the arthritic joints was similar in WT, MKK3−/−, and MKK6−/− mice (data not shown).

Figure 3.

Cytokine expression in CIA mice. (A) Gene expression in arthritic joints. Naive (n=3) and arthritic ankles (n≥10/group) were pulverized and gene expression was evaluated by quantitative PCR and normalized to HPRT. IL-6 expression was decreased in both MKK-deficient groups compared with WT (*p<0.05, One-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparison). (B) Serum IL-6 levels were measured using multiplex assays. Both MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice showed significantly lower IL-6 production compared with WT (n=18 WT, 12 MKK3−/−, 12 MKK6−/−, 3 naive, one-way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparison test, *=p<0.0002). (C) MMP3 and MMP13 expression was significantly reduced in MKK6−/− joints (*p<0.05).

Effect of MKK3- and MKK6-deficiency on p38 phosphorylation in CIA

In the K/BxN model, p38 phosphorylation was inhibited in MKK3−/− but not MKK6−/− arthritic joints (18). To determine the effect of MKK-deficiency on p38 phosphorylation in CIA, arthritic joint lysates were subjected to Western blot analysis (Figure 4). Similar to the K/BxN model, phospho-p38 (P-p38) expression was significantly lower in MKK3−/− compared with WT. However, P-p38 levels in MKK6−/− were comparable to WT mice. We next evaluated the phosphorylation status of STAT3, a key regulator of the IL-6 signaling pathway. Expression of P-STAT3 was significantly reduced in both MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− compared to WT mice, indicating that these kinases regulate both IL-6 production as well as signaling.

Figure 4.

Effect of MKK-deficiency on synovial kinase phosphorylation. Joint lysates from arthritic WT, MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice were evaluated by Western blot analysis. P-p38 levels were significantly lower in MKK3−/−, but not MKK6−/−, compared with WT mice (0.29±0.04 (n=9), 0.43±0.06 (n=8), 0.52±0.04 (n=13), respectively, p=0.008, one way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparison test). Expression of P-STAT3 was reduced significantly in both MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− arthritic joints compared with WT (2.0±0.3, 1.9±0.2, 3.6±0.4, respectively, p=0.005, one way ANOVA, Dunnett’s multiple comparison test).

Reduced anti-collagen antibody response in MKK6−/− mice

CIA pathogenesis is characterized by the generation of anti-type II collagen antibody production. The IgG2 subclass is particularly effective at binding complement and forming anti-collagen immune complexes in the synovium. Anti-collagen antibodies in serum were measured by ELISA (Figure 5). Total anti-type II collagen IgG antibody concentration was significantly reduced in MKK6−/− compared with WT mice. In contrast, total anti-collagen IgG1 was similar in MKK3−/− and WT mice even though disease severity was decreased in these mice. Regardless of isotype, anti-collagen antibodies were undetectable in naïve mice. These results suggest a potential role for MKK6 in regulating B cell responses and/or immunoglobulin isotype switching in response to collagen.

Figure 5.

Reduced anti-collagen response in MKK6−/− mice. Anti-collagen IgGs were measured in serum obtained on day 40 by ELISA. Total anti-collagen IgG as well as IgG2a subtype levels were significantly reduced in MKK6−/− but not MKK3−/− mice compared with WT (*p=0.024, p=0.037, t-test, n=12). In contrast, anti-collagen IgG1 levels were unaffected by MKK-deficiency.

T cell responses in MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− arthritic mice

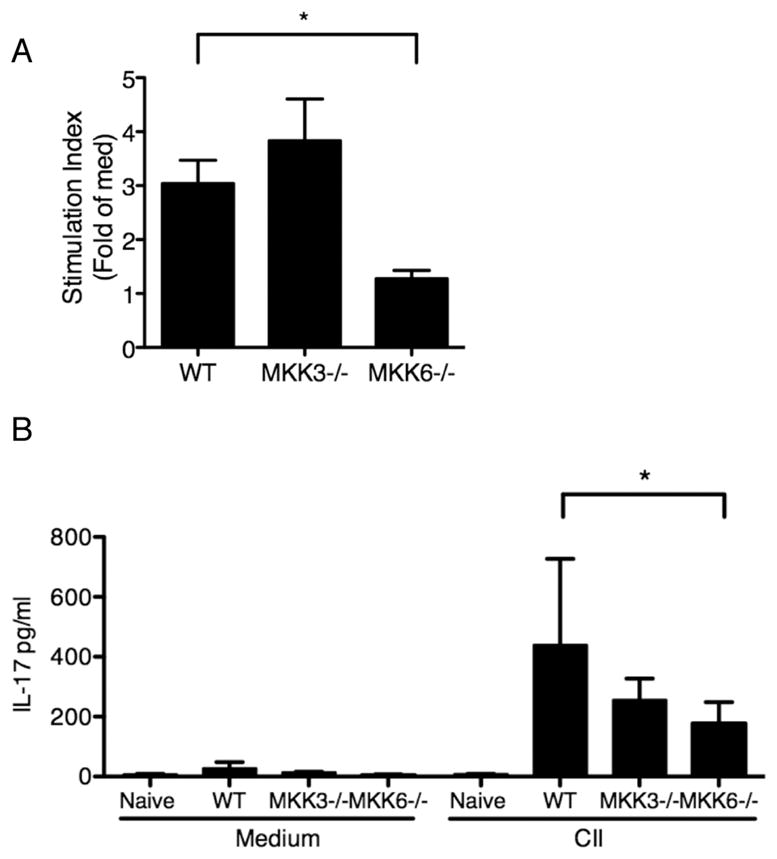

Induction and propagation of CIA requires functional T and B cells, and the anti-collagen antibody data show that this axis is suppressed in MKK6−/− mice. To evaluate the mechanism, we determined whether MKK3 and MKK6 regulate collagen-specific T-cell response in CIA Splenocytes and lymph node (LN) cells were isolated from collagen II-injected mice and cultured in vitro with the immunodominant CB11 collagen peptide. Proliferative response was assayed by 3H-thymidine incorporation (Figure 6A). MKK6−/− cells had significantly lower collagen-specific proliferative response compared with WT or MKK3−/− groups. Cytokine production in culture supernatants was quantified using multiplex bead analysis. IL-17 response to type II collagen peptide was significantly reduced in MKK6−/− compared with WT (Figure 6B). MKK3−/− cells showed a modest inhibition of IL-17 production compared with WT but did not reach statistical significance. IL-4 and IFNγ response to type II collagen peptide was low or undetectable in WT or MKK−/− cells. To determine if low IL-17 production by MKK6−/− cells was due to a deficiency in Th17 differentiation, WT and MKK−/− splenocytes and LN cells were cultured under Th17 polarizing conditions and analyzed by flow cytometry. The frequency of CD4+IL-17+ cells was similar in WT and MKK6−/− mice (5.14±1.83 and 3.84±2.21 fold of unstimulated cells, n=3 mice/group). Interestingly, the number of Th17 cells was modestly but consistently elevated in MKK3−/− mice (9.29±0.74, p=0.10, n=3). Together, these data indicate that MKK6 is an important regulator of collagen-specific Th17 response but not Th17 differentiation in CIA.

Figure 6.

Proliferation and cytokine analysis of splenocytes and lymph node cells from MKK−/− mice. (A) Animals were immunized with bovine collagen II and 10 days later the lymph node cells were isolated (n=3/group). The cells were stimulated in-vitro with collagen II peptide for 72h in triplicate and then incubated with 3H-thymidine for 24h. The cells were harvested and analyzed using a scintillation counter. Data are represented as stimulation index (CII cpm/med cpm). Proliferation was significantly reduced in MKK6−/− cells compared with WT. (B) IL-17 levels in cell culture supernatants were quantified using multiplex bead analysis. IL-17 production was significantly reduced in MKK6−/− group compared with WT cells in response to either stimulation. *p=0.037, t-test.

DISCUSSION

RA is a chronic inflammatory disease marked by synovial hyperplasia with local invasion of bone and cartilage. Synovitis is regulated by cytokines such as IL-6, TNF and IL-1 which trigger signaling cascades leading to the induction of inflammatory mediators, such as metalloproteinases (24). MAPKs, p38 in particular, can regulate expression and stability of pro-inflammatory cytokines that are expressed by RA synovium by activating downstream transcription factors such as activating transcription factor 2 (ATF2), AP-1, and MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MK2) (25).

p38 is activated by two homologous upstream kinases, MKK3 and MKK6, which are expressed and phosphorylated in the RA synovial lining (15). Phosphorylation of MKK3 and MKK6 is rapidly induced in FLS upon cytokine stimulation and inhibition of both kinases suppressed production of pro-inflammatory cytokines and proteases as efficiently as the p38 inhibitor, SB203580 (16). The functions of MKK3 and MKK6 vary considerably depending on the cell lineage and type of stimulus. To understand the contribution of these MKKs in inflammatory diseases, we previously evaluated K/BxN serum transfer arthritis in MKK3−/− or MKK6−/− mice (18). MKK3- or MKK6-deficient mice are healthy and viable while the absence of both MKKs is lethal (14, 26). MKK3-deficiency markedly decreased synovial inflammation without hindering innate immune responses to LPS (17). MKK6−/− mice exhibited reduced synovial inflammation, bone erosion and cartilage loss, similar to MKK3−/− mice (18). While MKK3 and MKK6 activated the p38 pathway, they regulated distinct subsets of pro-inflammatory cytokine production (18), possibly related to the specific phosphorylation sites on p38 and their contribution to stabilizing the p38-substrate complex.

The goal of the present study was to dissect the role of MKK3 and MKK6 in the CIA model. Unlike the K/BxN passive arthritis model, where innate immunity is necessary for synovial inflammation, CIA requires intact adaptive immune response, particularly through the generation of pathogenic collagen-specific T cells and anti-collagen antibodies (27). We showed that MKK3- or MKK6-deficiency markedly reduced arthritis scores compared with WT mice, with an especially prominent role for MKK6. Using micro-CT, the effects of CIA on bone morphometry were quantified and showed dramatic protection in the MKK6−/− mice. MKK3−/− mice also showed less damage than wild type mice, albeit less so. Three-dimensional reconstructions showed increased preservation of trabecular and cortical bone in arthritic MKK6−/− than WT mice. These data are consistent with the role of MKK6 in inducing osteoclast differentiation in vivo (28). Interestingly, MKK3-deficiency significantly reduced bone erosion, despite a more modest effect on inflammation, indicating that MKK3 has an important role in bone loss. Several groups have shown that MKK3 and p38α regulate osteoclast formation in response to DKK1 and RANK. We have also observed that MKK3 deficiency plays a more important role in in vitro osteoclast formation (manuscript in preparation). Inhibition of the p38 pathway using MKK3 siRNA or SB203580 significantly reduced TNF-induced osteoclastogenesis (29). Surprisingly, this effect was not observed with MKK6 siRNA. Others have shown that MKK6 is important for osteoclast differentiation and survival but not bone resorption activity by RANKL (28, 30). Together, our data indicate that MKK6 is more potent than MKK3 in regulating both inflammation and bone loss in CIA.

Expression of pro-inflammatory mediators in arthritic joints was evaluated to determine if the reduced disease activity in MKK6−/− was associated with a corresponding decrease in cytokines and MMPs. IL-6 gene expression was reduced in MKK6−/− and MKK3−/− arthritic joints mirroring serum IL-6 levels as well as disease scores. Interestingly, MMP3 and MMP13 gene expression in arthritic joints was significantly inhibited in MKK6−/− but not MKK3−/− mice. These data suggest that targeting MKK6 might inhibit IL-6 and MMP production in RA.

The marked inhibition of IL-6 production in MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice prompted our evaluation of IL-6-mediated signaling. A key regulator of the IL-6 pathway is STAT3, which dimerizes upon phosphorylation and induces transcription of pro-inflammatory IL-6 response genes (31). In this study, P-STAT3 levels were inhibited in arthritic MKK3−/− and MKK6−/− mice, reflecting deficiencies in local and systemic IL-6 expression. We also examined the effect of MKK3- and MKK6-deficiency on p38 activation in CIA. Phospho-p38 expression was significantly reduced in arthritic joints from MKK3−/− mice but not MKK6−/− animals. These data are consistent with our previous passive arthritis studies demonstrating that MKK3 and MKK6 differentially activate p38 (18). While MKK3 is required for p38 phosphorylation, MKK6 functions as a scaffold, enhancing interactions between p38 and its substrates.

Next, we evaluated the effect of MKK-deficiency on B and T cell function. MKK6−/− mice showed lower levels of total anti-collagen antibody than WT or MKK3−/− groups. In particular, anti-collagen IgG2a isotype, which efficiently fixes complement, was reduced in MKK6−/− mice. Interestingly, unlike MKK6, deficiency of MK2, a key p38 substrate that regulates cytokine production, does not affect anti-collagen antibody production in CIA (32). The effects that we observed on anti collagen antibodies were modest and did not correlate with the clinical benefit, especially in MKK3 deficient mice, suggesting alternate mechanisms. Previous studies show that MKK3 and MKK6 differentially regulate T cell development and function (33). MKK3−/− T cells are more resistant to activation-induced cell death than WT or MKK6−/− T cells, indicating that MKK3-deficiency might contribute to autoimmunity. However, we observed that MKK3−/− mice had reduced arthritis scores, indicating a more complex role for MKK3 in disease pathogenesis.

In vitro assays of T cell activity demonstrated decreased proliferative response to collagen peptide in MKK6−/− compared with WT or MKK3−/− cells. This contrasts other studies showing that neither MKK3 nor MKK6 is required for maximal proliferation of T cells in some circumstances (33), possibly due differences in the mice genetic background or the location of the T cells. Collagen-induced IL-17 production in the lymph node was significantly reduced in MKK6−/− culture supernatants, although a modest decrease was also observed in MKK3−/− group. Surprisingly, IL-17 gene expression was not detected in the arthritic joints despite the clear effects observed with ex vivo stimulation of draining lymph node T cells. The effect of MKK6 on Th17-mediated immunity, therefore, might occur in central lymphoid tissues rather than the joint, an observation consistent with a recent study showing that most of the IL-17 protein in RA synovial tissue is found in mast cells (34). It is intriguing that the absence of MKK3 or MKK6 did not inhibit Th17 differentiation, despite reduced IL-6 levels in these mice. However, others have shown that IL-21 can compensate for IL-6 in initiating Th17 differentiation (35). Together, these data demonstrate that MKK6-deficiency suppresses anti-collagen B and T cell responses, most likely through the inhibition of IL-17 production but not Th17 differentiation.

IL-17, derived mainly from Th17 cells, is a very critical regulator of joint inflammation, bone erosion and humoral response (36). IL-17− or IL-17-receptor deficiency suppresses inflammation and joint damage in CIA and IL-17 injection in normal mouse ankles induces synovitis and cartilage destruction (37–39). Decreased production of anti-collagen IgG2a in MKK6−/− serum might also be IL-17-dependent, since antibody class-switching to IgG2a is mediated by IL-17 (40). It is conceivable that the ameliorative effect of MKK6-deficiency in CIA is due to the combined inhibition of IL-6 and IL-17. This is consistent with studies demonstrating that IL-6 and IL-17 regulate each other through a positive feedback mechanism. In CIA, blocking IL-6 signaling preferentially inhibits Th17 responses and conversely, administration of anti-IL-17 antibody leads to a reduction in serum IL-6 levels (38, 41).

In conclusion, MKK3 and MKK6 regulate the adaptive immune response in CIA and suppress clinical disease and bone destruction. The effects on IL-17 production are especially interesting in light of recent studies demonstrating the benefit of an anti-IL-17 antibody in RA (42). The crucial role of MKK6 in synovial inflammation, cartilage loss, bone erosion as well as IL-17 production suggests that it might serve as a target of therapy in RA as an alternative to traditional p38 inhibitors.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health (AI070555 and AI067752)

We thank Dr. Maripat Corr and Josh Hillman for their assistance in this project.

Footnotes

Disclosures: none

References

- 1.Firestein GS. Evolving concepts of rheumatoid arthritis. Nature. 2003;423:356–61. doi: 10.1038/nature01661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bartok B, Firestein GS. Fibroblast-like synoviocytes: key effector cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:233–55. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00859.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen P. Targeting protein kinases for the development of anti-inflammatory drugs. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2009;21:317–24. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.01.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Schett G, Zwerina J, Firestein G. The p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) pathway in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008;67:909–16. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.074278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kumar S, Boehm J, Lee JC. p38 MAP kinases: key signalling molecules as therapeutic targets for inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:717–26. doi: 10.1038/nrd1177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee JC, Kumar S, Griswold DE, Underwood DC, Votta BJ, Adams JL. Inhibition of p38 MAP kinase as a therapeutic strategy. Immunopharmacology. 2000;47:185–201. doi: 10.1016/s0162-3109(00)00206-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Korb A, Tohidast-Akrad M, Cetin E, Axmann R, Smolen J, Schett G. Differential tissue expression and activation of p38 MAPK alpha, beta, gamma, and delta isoforms in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2006;54:2745–56. doi: 10.1002/art.22080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hammaker D, Firestein GS. “Go upstream, young man”: lessons learned from the p38 saga. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69 (Suppl 1):i77–82. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.119479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Page TH, Brown A, Timms EM, Foxwell BM, Ray KP. Inhibitors of p38 suppress cytokine production in rheumatoid arthritis synovial membranes: does variable inhibition of interleukin-6 production limit effectiveness in vivo? Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:3221–31. doi: 10.1002/art.27631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weinblatt ME, Kavanaugh A, Burgos-Vargas R, Dikranian AH, Medrano-Ramirez G, Morales-Torres JL, et al. Treatment of rheumatoid arthritis with a Syk kinase inhibitor: a twelve-week, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3309–18. doi: 10.1002/art.23992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Riese RJ, Krishnaswami S, Kremer J. Inhibition of JAK kinases in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: scientific rationale and clinical outcomes. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol. 2010;24:513–26. doi: 10.1016/j.berh.2010.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raingeaud J, Whitmarsh AJ, Barrett T, Derijard B, Davis RJ. MKK3- and MKK6-regulated gene expression is mediated by the p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase signal transduction pathway. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:1247–55. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.3.1247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brancho D, Tanaka N, Jaeschke A, Ventura JJ, Kelkar N, Tanaka Y, et al. Mechanism of p38 MAP kinase activation in vivo. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1969–78. doi: 10.1101/gad.1107303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wysk M, Yang DD, Lu HT, Flavell RA, Davis RJ. Requirement of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 (MKK3) for tumor necrosis factor-induced cytokine expression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:3763–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.7.3763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chabaud-Riou M, Firestein GS. Expression and activation of mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases-3 and -6 in rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Pathol. 2004;164:177–84. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)63108-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Inoue T, Hammaker D, Boyle DL, Firestein GS. Regulation of p38 MAPK by MAPK kinases 3 and 6 in fibroblast-like synoviocytes. J Immunol. 2005;174:4301–6. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.7.4301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inoue T, Boyle DL, Corr M, Hammaker D, Davis RJ, Flavell RA, et al. Mitogen-activated protein kinase kinase 3 is a pivotal pathway regulating p38 activation in inflammatory arthritis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:5484–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509188103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yoshizawa T, Hammaker D, Boyle DL, Corr M, Flavell R, Davis R, et al. Role of MAPK kinase 6 in arthritis: distinct mechanism of action in inflammation and cytokine expression. J Immunol. 2009;183:1360–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosengren S, Boyle DL, Firestein GS. Acquisition, culture, and phenotyping of synovial fibroblasts. Methods Mol Med. 2007;135:365–75. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-401-8_24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Simelyte E, Rosengren S, Boyle DL, Corr M, Green DR, Firestein GS. Regulation of arthritis by p53: critical role of adaptive immunity. Arthritis Rheum. 2005;52:1876–84. doi: 10.1002/art.21099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Han Z, Boyle DL, Manning AM, Firestein GS. AP-1 and NF-kappaB regulation in rheumatoid arthritis and murine collagen-induced arthritis. Autoimmunity. 1998;28:197–208. doi: 10.3109/08916939808995367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boyle DL, Rosengren S, Bugbee W, Kavanaugh A, Firestein GS. Quantitative biomarker analysis of synovial gene expression by real-time PCR. Arthritis Res Ther. 2003;5:R352–60. doi: 10.1186/ar1004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hammaker DR, Boyle DL, Inoue T, Firestein GS. Regulation of the JNK pathway by TGF-beta activated kinase 1 in rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes. Arthritis Res Ther. 2007;9:R57. doi: 10.1186/ar2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McInnes IB, O’Dell JR. State-of-the-art: rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:1898–906. doi: 10.1136/ard.2010.134684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Neininger A, Kontoyiannis D, Kotlyarov A, Winzen R, Eckert R, Volk HD, et al. MK2 targets AU-rich elements and regulates biosynthesis of tumor necrosis factor and interleukin-6 independently at different post-transcriptional levels. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:3065–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100685200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kang YJ, Seit-Nebi A, Davis RJ, Han J. Multiple activation mechanisms of p38alpha mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:26225–34. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606800200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brand DD, Kang AH, Rosloniec EF. Immunopathogenesis of collagen arthritis. Springer Semin Immunopathol. 2003;25:3–18. doi: 10.1007/s00281-003-0127-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Huang H, Ryu J, Ha J, Chang EJ, Kim HJ, Kim HM, et al. Osteoclast differentiation requires TAK1 and MKK6 for NFATc1 induction and NF-kappaB transactivation by RANKL. Cell Death Differ. 2006;13:1879–91. doi: 10.1038/sj.cdd.4401882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diarra D, Stolina M, Polzer K, Zwerina J, Ominsky MS, Dwyer D, et al. Dickkopf-1 is a master regulator of joint remodeling. Nat Med. 2007;13:156–63. doi: 10.1038/nm1538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yamashita T, Kobayashi Y, Mizoguchi T, Yamaki M, Miura T, Tanaka S, et al. MKK6-p38 MAPK signaling pathway enhances survival but not bone-resorbing activity of osteoclasts. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2008;365:252–7. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.10.169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nowell MA, Williams AS, Carty SA, Scheller J, Hayes AJ, Jones GW, et al. Therapeutic targeting of IL-6 trans signaling counteracts STAT3 control of experimental inflammatory arthritis. J Immunol. 2009;182:613–22. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hegen M, Gaestel M, Nickerson-Nutter CL, Lin LL, Telliez JB. MAPKAP kinase 2-deficient mice are resistant to collagen-induced arthritis. J Immunol. 2006;177:1913–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.177.3.1913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tanaka N, Kamanaka M, Enslen H, Dong C, Wysk M, Davis RJ, et al. Differential involvement of p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase kinases MKK3 and MKK6 in T-cell apoptosis. EMBO Rep. 2002;3:785–91. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hueber AJ, Asquith DL, Miller AM, Reilly J, Kerr S, Leipe J, et al. Mast cells express IL-17A in rheumatoid arthritis synovium. J Immunol. 2010;184:3336–40. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Korn T, Bettelli E, Gao W, Awasthi A, Jager A, Strom TB, et al. IL-21 initiates an alternative pathway to induce proinflammatory T(H)17 cells. Nature. 2007;448:484–7. doi: 10.1038/nature05970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Peck A, Mellins ED. Breaking old paradigms: Th17 cells in autoimmune arthritis. Clin Immunol. 2009;132:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.03.522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lubberts E, Joosten LA, van de Loo FA, Schwarzenberger P, Kolls J, van den Berg WB. Overexpression of IL-17 in the knee joint of collagen type II immunized mice promotes collagen arthritis and aggravates joint destruction. Inflamm Res. 2002;51:102–4. doi: 10.1007/BF02684010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lubberts E, Koenders MI, Oppers-Walgreen B, van den Bersselaar L, Coenen-de Roo CJ, Joosten LA, et al. Treatment with a neutralizing anti-murine interleukin-17 antibody after the onset of collagen-induced arthritis reduces joint inflammation, cartilage destruction, and bone erosion. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:650–9. doi: 10.1002/art.20001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chabaud M, Lubberts E, Joosten L, van Den Berg W, Miossec P. IL-17 derived from juxta-articular bone and synovium contributes to joint degradation in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. 2001;3:168–77. doi: 10.1186/ar294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mitsdoerffer M, Lee Y, Jager A, Kim HJ, Korn T, Kolls JK, et al. Proinflammatory T helper type 17 cells are effective B-cell helpers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:14292–7. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009234107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujimoto M, Serada S, Mihara M, Uchiyama Y, Yoshida H, Koike N, et al. Interleukin-6 blockade suppresses autoimmune arthritis in mice by the inhibition of inflammatory Th17 responses. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:3710–9. doi: 10.1002/art.24126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Genovese MC, Van den Bosch F, Roberson SA, Bojin S, Biagini IM, Ryan P, et al. LY2439821, a humanized anti-interleukin-17 monoclonal antibody, in the treatment of patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A phase I randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, proof-of-concept study. Arthritis Rheum. 2010;62:929–39. doi: 10.1002/art.27334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]