Summary

Most patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) die from progressive disease after relapse, which is associated with clonal evolution at the cytogenetic level1,2. To determine the mutational spectrum associated with relapse, we sequenced the primary tumor and relapse genomes from 8 AML patients, and validated hundreds of somatic mutations using deep sequencing; this allowed us to precisely define clonality and clonal evolution patterns at relapse. Besides discovering novel, recurrently mutated genes (e.g. WAC, SMC3, DIS3, DDX41, and DAXX) in AML, we found two major clonal evolution patterns during AML relapse: 1) the founding clone in the primary tumor gained mutations and evolved into the relapse clone, or 2) a subclone of the founding clone survived initial therapy, gained additional mutations, and expanded at relapse. In all cases, chemotherapy failed to eradicate the founding clone. The comparison of relapse-specific vs. primary tumor mutations in all 8 cases revealed an increase in transversions, probably due to DNA damage caused by cytotoxic chemotherapy. These data demonstrate that AML relapse is associated with the addition of new mutations and clonal evolution, which is shaped in part by the chemotherapy that the patients receive to establish and maintain remissions.

Results

To investigate the genetic changes associated with AML relapse, and to determine whether clonal evolution contributes to relapse, we performed whole genome sequencing of primary tumor-relapse pairs and matched skin samples from 8 patients, including UPN 933124, whose primary tumor mutations were previously reported3. Informed consent explicit for whole genome sequencing was obtained for all patients on a protocol approved by the Washington University Medical School Institutional Review Board. We obtained >25X haploid coverage and >97% diploid coverage for each sample (Supplementary Table 1 and Supplementary Information). These patients were from five different French-American-British (FAB) hematologic subtypes, with elapsed times of 235 to 961 days between initial diagnosis and relapse (Supplementary Table 2a and 2b).

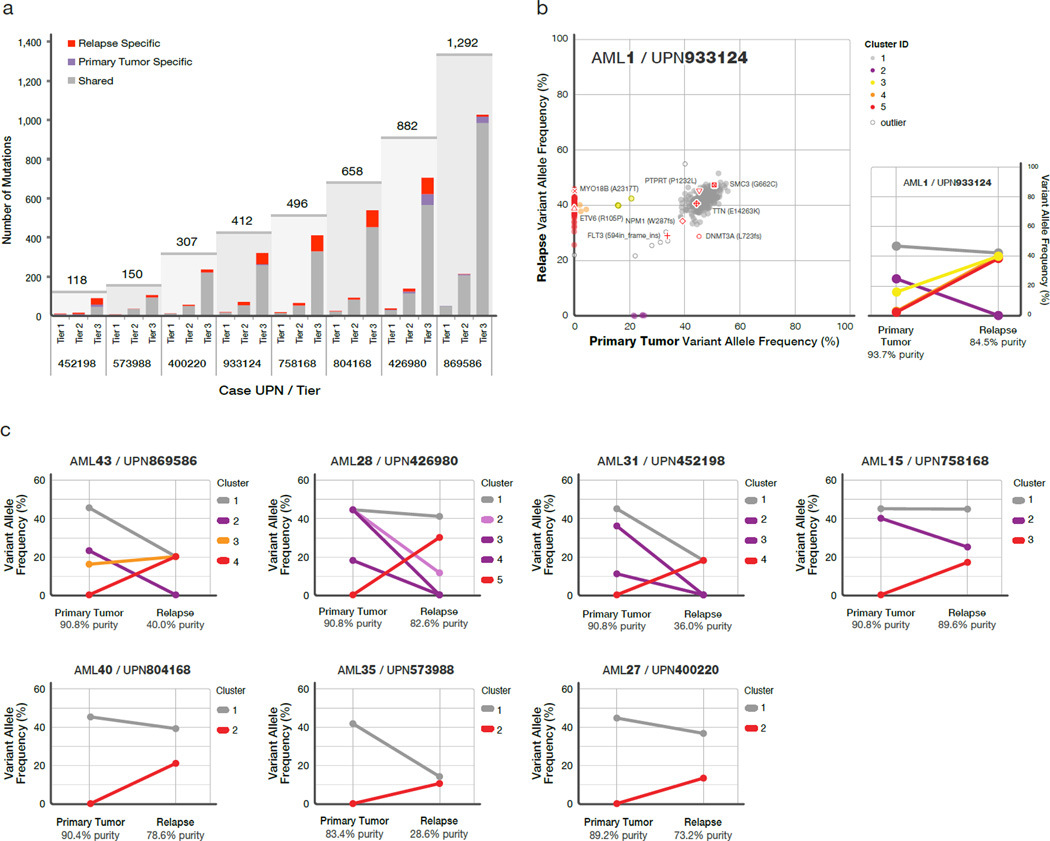

Candidate somatic events in the primary tumor and relapse genomes were identified4,5 and selected for hybridization capture-based validation using methods described in Supplementary Information. Deep sequencing of the captured target DNAs from skin (the matched normal tissue), primary tumor, and relapse tumor specimens6 (Supplementary Table 3) yielded a median of 590 fold coverage per site. The average number of mutations and structural variants was 539 (range 118 – 1,292) per case (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1. Somatic mutations quantified by deep sequencing of capture validation targets in 8 acute myeloid leukemia primary tumor and relapse pairs.

a) Summary of tier 1–3 mutations detected in 8 cases. All mutations shown were validated using capture followed by deep sequencing. Shared mutations are in gray, primary tumor specific mutations in purple, and relapse-specific mutations in red. The total number of tier 1–3 mutations for each case is shown above the light gray rectangle. b) Mutant allele frequency distribution of validated mutations from tier 1–3 in the primary tumor and relapse of case UPN 933124 (left). Mutant allele frequencies for 5 primary tumor specific mutations were obtained from a 454 deep readcount experiment. Four mutation clusters were identified in the primary tumor, and one was found at relapse. Five low-level mutations from known copy number variable regions were excluded from clustering analysis. Non-synonymous mutations from genes that are recurrently mutated in AML are shown. The change of mutant allele frequencies for mutations from the 5 clusters is shown (right) between the primary tumor and relapse. c) The mutation clusters detected in the primary tumor and relapse samples from 7 additional AML patients. The relationship between clusters in the primary tumor and relapse samples are indicated by lines linking them. Cluster: a group of mutations with similar allele frequencies, likely derived from the same clone. Clone: a group of cells with identical mutation content.

The general approach for relapse analysis is exemplified by the first sequenced case (UPN 933124). A total of 413 somatic events from tiers 1 to 3 were validated (see Mardis et al.7 for tier designations; Supplementary Fig. 1a, Supplementary Tables 4a and 5). Of these, 78 mutations were relapse-specific (63 point mutations, 1 dinucleotide mutation, 13 indels, and 1 translocation; relapse-specific criteria described in Supplementary Information and shown in Supplementary Fig. 1b), 5 point mutations were primary tumor-specific, and 330 (317 point mutations and 13 indels) were shared between the primary tumor and relapse samples (Fig. 1a, Fig. 1b, and Supplementary Fig. 2). The skin sample was contaminated with leukemic cells for this case (peripheral WBC count was 105,000 cells/mm^3 when the skin sample was banked), with an estimated tumor content in the skin sample of 29% (Supplementary Information). In addition to the ten somatic nonsynonymous mutations originally reported for the primary tumor sample3, we identified one deletion that was not detected in the original analysis (DNMT3A L723fs8) and three missense mutations previously misclassified as germline events (SMC3 G662C, PDXDC1 E421K, and TTN E14263K) (Fig. 1b, Table 1, and Supplementary Table 4b).

Table 1.

Coding mutations identified in 8 primary tumor-relapse pairs.

| UPN | Tier 1 mutations (primary/relapse) | Total mutations (primary/relapse) | Recurrently mutated genes in primary tumor | Relapse-specific nonsynonymous somatic mutations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 452198 | 9/9 | 76/99 | DNMT3A, NPM1, FLT3, IDH1 | none |

| 573988 | 6/8 | 135/150 | NPM1, IDH2 | STOX2 |

| 804168 | 22/26 | 558/658 | FLT3, WT1, PHF6, FAM5C, TTC39A | SLC25A12, RIPK4, ABCD2 |

| 933124 | 16/19 | 336/407 | DNMT3A, NPM1, FLT3, TTN, SMC3, PTPRT | ETV6*, MYO18B*, WAC** *, STK4 |

| 400220 | 12/13 | 285/306 | FLT3, RUNX1, WT1, PLEKHH1 | none |

| 426980 | 32/35 | 777/816 | IDH2, MYO1F, DDX4 | GBP4, DCLK1, IDH2*, DCLK1*, ZNF260 |

| 758168 | 15/19 | 397/496 | DNAH9, DIS3, CNTN5, PML-RARA** | ENSG00000180144, DAGLA* |

| 869586 | 51/50 | 1280/1254 | RUNX1, WT1, TTN, PHF6, NF1, SUZ12, NCOA7, EED, DAXX, ACSS3, WAC, NUMA1 | none |

Tier 1 mutation counts exclude RNA genes.

Recurrent mutations occurring in relapse sample.

Translocations were not included in tier 1 mutation counts

A total of 169 tier 1 coding mutations (approximately 21 per case) were identified in the 8 patients (Table 1, Supplementary Tables 4b and 6), of which 19 were relapse-specific. In addition to mutations in known AML genes such as DNMT3A8, FLT39, NPM110, IDH17, IDH211, WT112, RUNX113,14, PTPRT3, PHF615, and ETV616 in these 8 patients, we also discovered novel, recurring mutations in WAC, SMC3, DIS3, DDX41, and DAXX using 200 AML cases whose exomes were sequenced as part of the The Cancer Genome Atlas AML project (Table 1, Supplementary Table 4b, and Supplementary Fig. 3; T.J. Ley, R.K. Wilson, and The Cancer Genome Atlas working group on AML, unpublished). Details regarding the novel recurring mutations are provided in the Supplementary Information, Table 1, Supplementary Tables 4b and 7, and Supplementary Figures 3 and 4.

Structural and functional analyses of structural variants are presented in the Supplementary Information (Supplementary Figures 5–10 and Supplementary Tables 2, 8, and 9).

The generation of high depth sequencing data allowed us to accurately quantify mutant allele frequencies in all cases, permitting estimation of the size of tumor clonal populations in each AML sample. Based on mutation clustering results, we inferred the identity of four clones having distinct sets of mutations (clusters) in the primary tumor of AML1/UPN 933124 (Supplementary Information). The median mutant allele frequencies in the primary tumor for clusters 1 to 4 were 46.86%, 24.89%, 16.00%, and 2.39%, respectively (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Table 5c). Clone 1 is the “founding” clone (i.e. the other subclones are derived from it), containing the cluster 1 mutations; assuming that nearly all of these mutations are heterozygous, they must be present in virtually all the tumor cells at presentation and at relapse, since the variant frequency of these mutations is ~40–50%. Clone 2 (with cluster 2 mutations) and clone 3 (with cluster 3 mutations) must be derived from clone 1, since virtually all the cells in the sample contain the cluster 1 mutations (Fig. 2a). It is likely that a single cell from clone 3 gained a set of mutations (cluster 4) to form clone 4: these survived chemotherapy and evolved to become the dominant clone at relapse. We do not know whether any of the cluster 4 mutations conferred chemotherapy resistance; although none had translational consequences, we cannot rule out a relevant regulatory mutation in this cluster.

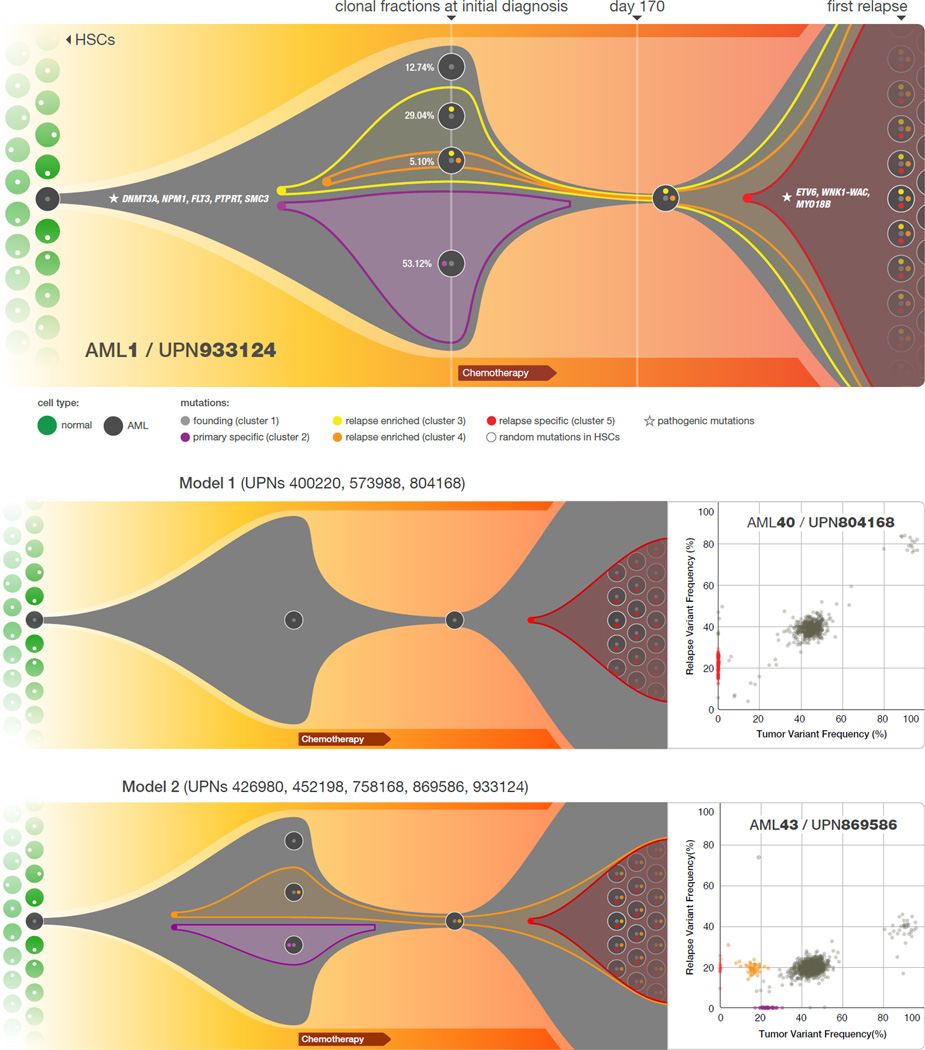

Figure 2. Graphical representation of clonal evolution from the primary tumor to relapse in UPN 933124, and patterns of tumor evolution observed in 8 primary tumor and relapse pairs.

a) The founding clone in the primary tumor in UPN 933124 contained somatic mutations in DNMT3A, NPM1, PTPRT, SMC3, and FLT3 that are all recurrent in AML and probably relevant for pathogenesis; one subclone within the founding clone evolved to become the dominant clone at relapse by acquiring additional mutations, including recurrent mutations in ETV6 and MYO18B, and a WNK1-WAC fusion gene. HSC: hematopoietic stem cell. b) Examples of the two major patterns of tumor evolution in AML: Model 1 shows the dominant clone in the primary tumor evolving into the relapse clone by gaining relapse-specific mutations; this pattern was identified in 3 primary tumor and relapse pairs (UPNs 804168, 573988, and 400220). Model 2 shows a minor clone carrying the vast majority of the primary tumor mutations survived and expanded at relapse. This pattern was observed in 5 primary tumor and relapse pairs (UPNs 933124, 452198, 758168, 426980, and 869586).

Assuming that all the mutations detected are heterozygous in the primary tumor sample (with a malignant cellular content at 93.72% for the primary bone marrow sample, see Supplementary Information), we were able to calculate the fraction of total malignant cells in each clone. Clone 1 is the founding clone; 12.74% of the tumor cells contain only this set of mutations. Clones 2, 3, and 4 evolved from clone 1. The additional mutations in clones 2 and 3 may have provided a growth or survival advantage, since 53.12% and 29.04% of the tumor cells belonged to these clones, respectively. Only 5.10% of the tumor cells were from clone 4, suggesting that it may have arisen last (Fig. 2a). However, the relapse clone evolved from clone 4. A single clone containing all of the cluster 5 mutations was detected in the relapse sample; clone 5 evolved from clone 4, but gained 78 new somatic alterations after sampling at day 170. Since all mutations in clone 5 appear to be present in all relapse tumor cells, we suspect that one or more of the mutations in this clone provided a strong selective advantage that contributed to relapse. The ETV6 mutation, the MYO18B mutation, and/or the WNK1-WAC fusion are the most likely candidates, since ETV6, MYO18B, and WAC are recurrently mutated in AML.

We evaluated the mutation clusters in the 7 additional primary tumor-relapse pairs by assessing peaks of allele frequency using kernel density estimation (KDE) (Supplementary Fig. 11 and Supplementary Information). We thus inferred the numbers and malignant fractions of clones in each primary tumor and relapse sample. Similar to UPN 933124, multiple mutation clusters (2 to 4) were present in each of the primary tumors from 4 patients (UPNs: 869586, 426980, 452198, and 758168). However, only one major cluster was detected in each of the primary tumors from the 3 other patients (UPNs: 804168, 573988, and 400220) (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Table 10). Importantly, all 8 patients gained relapse-specific mutations, although the number of clusters in the relapse samples varied (Fig. 1).

Two major patterns of clonal evolution were detected at relapse (Fig. 2b and Supplementary Fig. 3): In cases with Pattern 1, the dominant clone in the primary tumor gained additional mutations and evolved into the relapse clone (UPNs: 804168, 573988, and 400220). These patients may simply be inadequately treated (e.g. elderly patients who cannot tolerate aggressive consolidation, like UPN 573988), or they may have mutations in their founding clones (or germline variants) that make these cells more resistant to therapy (UPNs 804168 and 400220). In patients with Pattern 2, a minor subclone carrying the vast majority (but not all) of the primary tumor mutations survived, gained mutations, and expanded at relapse; a subset of primary tumor mutations were often eradicated by therapy, and were not detected at relapse (UPNs: 758168, 933124, 452198, 426980, and 869586). Specific mutations in a key subclone may contribute to chemotherapy resistance, or the mutations important for relapse may be acquired during tumor evolution, or both. Notably, in cases 426980 and 758168, a second primary tumor clone survived chemotherapy and was also present at relapse (Fig. 1c and Supplementary Fig. 3). Due to current technical limits in our ability to detect mutations in rare cells (mostly related to currently achievable levels of coverage with whole genome sequencing), our models represent a minimal estimate of the clonal heterogeneity in AML.

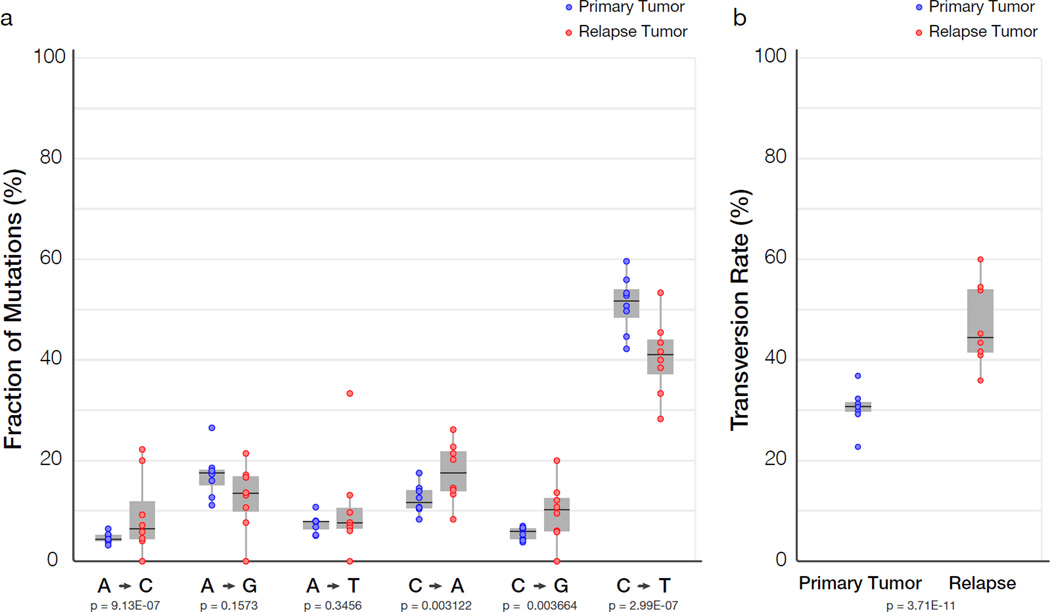

All 8 patients received cytarabine and anthracycline for induction therapy, and additional cytotoxic chemotherapy for consolidation; treatment histories are summarized in Supplementary Table 2 and described in Supplementary Information. To investigate the potential impact of treatment on relapse mutation types, we compared the six classes of transition and transversion mutations in the primary tumor with the relapse-specific mutations in all 8 patients (Fig. 3a). Although C:G->T:A transitions are the most common mutations found in both primary and relapse AML genomes, their frequencies are significantly different between the primary tumor mutations (51.1%) and relapse-specific mutations (40.5%) (P = 2.99E-7). Moreover, we observed an average of 4.5%, 5.3%, 4.2% increases in A:T->C:G (P = 9.13E-7), C:G->A:T (P = 0.00312), and C:G->G:C (P = 0.00366) transversions, respectively, in relapse-specific mutations; of note, increased A:T->C:G transversion rate has also been observed in cases of chronic lymphocytic leukemia with mutated immunoglobulin genes17. C:G->A:T transversions are the most common mutation in lung cancer patients who were exposed to tobacco-borne carcinogens18 (Fig. 3b and Supplementary Table 11). We examined the 456 relapse-specific mutations and 3590 primary tumor point mutations from all 8 cases as a group, and found that the transversion frequency is significantly higher for relapse-specific mutations (46%) than for primary tumor mutations (30.7%) (P = 3.71E-11), suggesting that chemotherapy has a substantial effect on the mutational spectrum at relapse. Similar results were obtained when we limited the analysis to the 213 mutations that had 0% variant frequency in the primary tumor samples (Supplementary Fig. 1b); the transversion frequency for relapse-specific mutations was 50.4%, vs. 31.4% for primary tumor samples (P = 3.89E-09). Very few copy number alterations were detected in the 8 relapse samples, suggesting that the increased transversion rate is not associated with generalized genomic instability (Supplementary Fig. 12).

Figure 3. Comparison of mutational classes between primary tumors and relapse samples.

a) Fraction of the primary tumor and relapse-specific mutations in each of the transition and transversion categories. b) Transversion frequencies of the primary tumor and relapse-specific mutations from 8 AML tumor and relapse pairs. 456 relapse-specific mutations and 3590 primary tumor mutations from 8 cases were used for assessing statistical significance using proportion tests.

Discussion

We first described the use of deep sequencing to precisely define the variant allele frequencies of the mutations in the AML genome of case 9331243, and here have refined and extended this technique to examine clonal evolution at relapse. The analysis of 8 primary AML and relapse pairs has revealed unequivocal evidence for a common origin of tumor subpopulations; a dominant mutation cluster representing the founding clone was discovered in the primary tumor sample in all cases. The relationship of the founding clone (and subclones thereof) to the “leukemia initiating cell” is not yet clear; purification of clonal populations and functional testing would be required to establish this relationship. We observed the loss of primary tumor subclones at relapse in 4 of 8 cases, suggesting that some subclones are indeed eradicated by therapy (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, and Supplementary Fig. 3). Some mutations gained at relapse may alter the growth properties of AML cells, or confer resistance to additional chemotherapy. Regardless, each tumor displayed clear evidence of clonal evolution at relapse, and a higher frequency of transversions that were probably induced by DNA damage from chemotherapy. Although chemotherapy is required to induce initial remissions in AML patients, our data also raise the possibility that it contributes to relapse by generating new mutations in the founding clone or one of its subclones, which then can undergo selection and clonal expansion. These data demonstrate the critical need to identify the disease-causing mutations for AML, so that targeted therapies can be developed that avoid the use of cytotoxic drugs, many of which are mutagens.

This study extends the findings of Mullighan et al.19, Anderson et al.20, and Notta et al.21, who recently described patterns of clonal evolution in ALL patients using FISH and/or copy number alterations detected by SNP arrays, and it enhances the understanding of genetic changes acquired during disease progression, as previously described for breast and pancreatic cancer metastases 22–25. Our data provide complementary information on clonal evolution in AML, using a much larger set of mutations that were quantified with deep sequencing; this provides an unprecedented number of events that can be used to precisely define clonal size, and mutational evolution at relapse. Both ALL and AML share common features of clonal heterogeneity at presentation followed by dynamic clonal evolution at relapse, including the addition of new mutations that may be relevant for relapse pathogenesis. Similar clonal evolutionary patterns have been detected during the progression of myelodysplasia to AML (M.J. Walter et al., submitted), suggesting that these are common features of AML evolution; clonal evolution can also occur after allogeneic transplantation (e.g. loss of mismatched HLA alleles via a uniparental disomy mechanism), demonstrating that the type of therapy itself can affect clonal evolution at relapse26,27. Taken together, these data demonstrate that AML cells routinely acquire a small number of additional mutations at relapse, and suggest that some of these mutations may contribute to clonal selection and chemotherapy resistance. The AML genome in an individual patient is clearly a “moving target”; eradication of the founding clone and all of its subclones will be required to achieve cures.

Methods Summary

Illumina paired end reads were aligned to NCBI build36 using BWA 0.5.5 (http://sourceforge.net/projects/bio-bwa/). Somatic mutations were identified using SomaticSniper (D. Larson et al., in press) and a modified version of the SAMtools indel caller. Structural variations were identified using BreakDancer5. All predicted non-repetitive somatic SNVs, indels, and all structural variants were included on custom sequence capture arrays from Roche Nimblegen. Illumina 2 × 100 bp paired end sequencing reads were produced following elution from capture arrays. VarScan6 and a read remapping strategy utilizing Crossmatch (Phil Green, unpublished) and BWA were used for determining the validation status of predicted SNVs, indels, and structural variants. A complete description of the materials and methods is provided in Supplementary Information. All sequence variants for the AML tumor samples from 8 cases have been submitted to dbGaP (accession number phs000159.v3.p2).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank the Analysis Pipeline group for developing the automated sequence analysis pipelines; the LIMS group for developing tools and software to manage samples and sequencing; and the Systems group for providing the IT infrastructure and HPC solutions required for sequencing and analysis. We also thank The Cancer Genome Atlas for allowing us to use unpublished data for this study, and the Washington University Cancer Genome Initiative for their support. This work was funded by grants to Richard K. Wilson from Washington University in St. Louis and the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI U54 HG003079), and grants to Timothy J. Ley from the National Cancer Institute (PO1 CA101937) and the Barnes-Jewish Hospital Foundation (00335-0505-02).

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.J.L., L.D., J.F.D., E.R.M., and R.K.W. designed the experiments. L. D. and T.J.L. led data analysis. L.D., D.E.L., C.A.M., D.C.K., J.S.W., M.D.M., J.W.W., C.L., D.S., C.C.H., K.C., H.S., J.K., M.C.W., M.A.W., W.D.S., J.E.P., and S.K. performed data analysis. J.F.M., M.D.M., and L.D. prepared figures and tables. J.S.W., J.K.R., M.A.Y., T.L., R.S.F., L.L.F., V.J.M., L.S., S.D.M., and T.L.V. performed laboratory experiments. S.H. and P.W. provided samples and clinical data. D.J.D. provided informatics support. T.J.L., D.C.L., M.H.T., E.R.M., R.K.W., and J.F.D. developed project concept. L.D., T.J.L., M.J.W., T.A.G., and J.F.D. wrote the manuscript.

References

- 1.Testa JR, Mintz U, Rowley JD, Vardiman JW, Golomb HM. Evolution of karyotypes in acute nonlymphocytic leukemia. Cancer Res. 1979;39:3619–3627. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garson OM, et al. Cytogenetic studies of 103 patients with acute myelogenous leukemia in relapse. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 1989;40:187–202. doi: 10.1016/0165-4608(89)90024-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ley TJ, et al. DNA sequencing of a cytogenetically normal acute myeloid leukaemia genome. Nature. 2008;456:66–72. doi: 10.1038/nature07485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li H, et al. The Sequence Alignment/Map (SAM) Format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2009 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen K, et al. BreakDancer: an algorithm for high-resolution mapping of genomic structural variation. Nat Methods. 2009;6:677–681. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Koboldt DC, et al. VarScan: Variant detection in massively parallel sequencing of individual and pooled samples. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England) 2009 doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mardis ER, et al. Recurring mutations found by sequencing an acute myeloid leukemia genome. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:1058–1066. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0903840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ley TJ, et al. DNMT3A mutations in acute myeloid leukemia. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2424–2433. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Nakao M, et al. Internal tandem duplication of the flt3 gene found in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 1996;10:1911–1918. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noguera NI, et al. Simultaneous detection of NPM1 and FLT3-ITD mutations by capillary electrophoresis in acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2005;19:1479–1482. doi: 10.1038/sj.leu.2403846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward PS, et al. The common feature of leukemia-associated IDH1 and IDH2 mutations is a neomorphic enzyme activity converting alpha-ketoglutarate to 2-hydroxyglutarate. Cancer Cell. 2010;17:225–234. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.01.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.King-Underwood L, Renshaw J, Pritchard-Jones K. Mutations in the Wilms' tumor gene WT1 in leukemias. Blood. 1996;87:2171–2179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gao J, et al. Isolation of a yeast artificial chromosome spanning the 8;21 translocation breakpoint t(8;21)(q22;q22.3) in acute myelogenous leukemia. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:4882–4886. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.11.4882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirito K, et al. A novel RUNX1 mutation in familial platelet disorder with propensity to develop myeloid malignancies. Haematologica. 2008;93:155–156. doi: 10.3324/haematol.12050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Van Vlierberghe P, et al. PHF6 mutations in adult acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia. 2011;25:130–134. doi: 10.1038/leu.2010.247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Barjesteh van Waalwijk van Doorn-Khosrovani S, et al. Somatic heterozygous mutations in ETV6 (TEL) and frequent absence of ETV6 protein in acute myeloid leukemia. Oncogene. 2005;24:4129–4137. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Puente XS, et al. Whole-genome sequencing identifies recurrent mutations in chronic lymphocytic leukaemia. Nature. 2011;475:101–105. doi: 10.1038/nature10113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding L, et al. Somatic mutations affect key pathways in lung adenocarcinoma. Nature. 2008;455:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature07423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mullighan CG, et al. Genomic analysis of the clonal origins of relapsed acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Science. 2008;322:1377–1380. doi: 10.1126/science.1164266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Anderson K, et al. Genetic variegation of clonal architecture and propagating cells in leukaemia. Nature. 2011;469:356–361. doi: 10.1038/nature09650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Notta F, et al. Evolution of human BCR-ABL1 lymphoblastic leukaemia-initiating cells. Nature. 2011;469:362–367. doi: 10.1038/nature09733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ding L, et al. Genome remodelling in a basal-like breast cancer metastasis and xenograft. Nature. 2010;464:999–1005. doi: 10.1038/nature08989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shah SP, et al. Mutational evolution in a lobular breast tumour profiled at single nucleotide resolution. Nature. 2009;461:809–813. doi: 10.1038/nature08489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yachida S, et al. Distant metastasis occurs late during the genetic evolution of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2010;467:1114–1117. doi: 10.1038/nature09515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Navin N, et al. Tumour evolution inferred by single-cell sequencing. Nature. 2011 doi: 10.1038/nature09807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vago L, et al. Loss of mismatched HLA in leukemia after stem-cell transplantation. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:478–488. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0811036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Villalobos IB, et al. Relapse of leukemia with loss of mismatched HLA resulting from uniparental disomy after haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Blood. 2010;115:3158–3161. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-11-254284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.