Abstract

A 54-year-old man presented with blurred central vision in the right eye of two weeks' duration. On presentation, visual acuity was 40 / 50 in the right eye and fundus examination showed a whitish-yellow inflammatory lesion near an atrophic, pigmented retinochoroidal scar located in the superotemporal quadrant. Serologic assessment was negative for IgM, but serum IgG to toxoplasma was elevated. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT) revealed increased reflectivity from the inner retinal layer, retinal thickening, and choroidal shadowing while focal posterior hyaloid thickening and detachment were observed in the new lesion. He was treated with trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole, clindamycin, and prednisone. SD-OCT is helpful for definitively differentiating ocular toxoplasmosis from other retinal diseases.

Keywords: Ocular toxoplasmosis, Retinochoroiditis, Spectral domain optical coherence tomography

Toxoplasma gondii infection is distributed worldwide and toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis is the most common form of posterior uveitis in otherwise healthy individuals [1]. The eyes appear to be especially susceptible to Toxoplasma infection, which may be a result of the blood-retinal barrier that limits antibody penetration to the ocular tissues. If a parasite reaches the eye, the focus of infection is established, which progresses from retinitis to secondarily involve the choroid. The host's immune response appears to induce the conversion of the tachyzoite to bradyzoite and encystment in the Toxoplasma life cycle, and a large number of T cells are found in retinal lesions and in the choroid. Infiltrating T lymphocytes may play a role in the early recognition of Toxoplasma in the eye. Healing of the lesion occurs with control of the acute infection and scar formation. The cyst may remain inactive in the scar or adjacent to it for a period of years. Ultimately, the cyst wall may rupture, releasing organisms into the surrounding retina and resulting in recurring retinitis. As a result, the initial lesion can cause damage to the inner retinal layers adjacent to an old chorioretinal scar and can be accompanied by vitritis [2]. Here, we review a case of ocular toxoplasmosis imaged using spectral domain optical coherence tomography (SD-OCT; Cirrus HD-OCT, Carl Zeiss Meditec Inc., Dublin, CA, USA). Visual acuity, fluorescein angiography (FAG), blood serology and treatment are also discussed.

Case Report

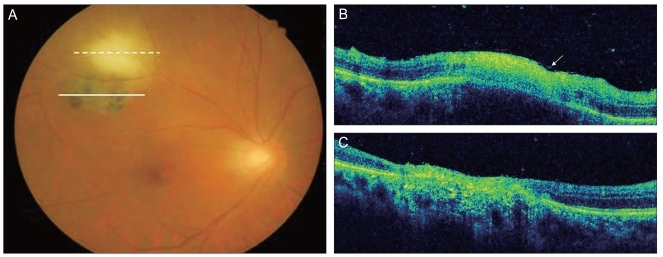

A 54-year-old man presented with blurred central vision in the right eye of two weeks' duration. On presentation, visual acuity was 40 / 50 in the right eye and 20 / 20 in the left eye. Anterior and posterior segment examination of the left eye was unremarkable. On exam, the right eye exhibited mild inflammation in the anterior chamber and the vitreous. Fundus examination showed a whitish-yellow inflammatory lesion near an atrophic, pigmented retinochoroidal scar located in the superotemporal quadrant (Fig. 1A). Hyperfluorescence on early-phase FAG was observed at the margin of the old pigmented lesion and in the new lesion (Fig. 2A). The new lesion also showed hyperfluorescence in the late phase (Fig. 2B). SD-OCT showed increased reflectivity from the inner retinal layer, retinal thickening, and choroidal shadowing. Focal posterior hyaloid thickening and detachment were observed in the new lesion (Fig. 1B). In the old lesion, SD-OCT showed hyperreflectivity, thinning of the neurosensory retina and a disorganized retinal pigment epithelium (RPE) layer (Fig. 2C). Serum IgM was negative but an elevated serum level of IgG (75 IU/mL; reference value, <4 IU/mL) to toxoplasma was observed. A syphilis evaluation and other tests which were toxocariasis and rheumatologic tests were negative. A presumptive diagnosis of toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis was made and a regimen of trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole 960 mg po bid and clindamycin 150 mg po qid was started. Prednisone (30 mg/day) was added and tapered over a period of four weeks. Six weeks later, the lesion had resolved (Fig. 3A) and the patient's right-eye visual acuity had improved to 20 / 20. SD-OCT performed after treatment showed thinning of the retina, a disorganized RPE layer and posterior hyaloid detachment (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 1.

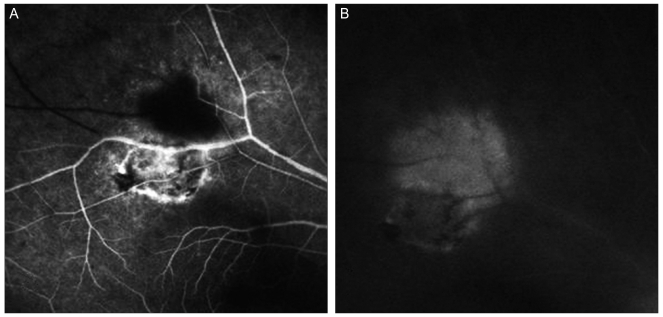

(A) Hyperfluorescence was observed at the margin of the old lesion and in the new lesion on early phase fluorescein angiography. (B) The new lesion showed hyperfluorescence in the late-phase.

Fig. 2.

(A) Fundus photography revealed a whitish-yellow inflammatory lesion near an atrophic, pigmented retinochoroidal scar located in the superotemporal quadrant. (B) Spectral domain optical coherence tomography showed increased reflectivity from the inner retinal layer, retinal thickening and choroidal shadowing. Focal posterior hyaloid thickening and detachment were also observed (arrow). (C) Hyperreflectivity, thinning of the neurosensory retina and a disorganized retinal pigment epithelium layer were observed.

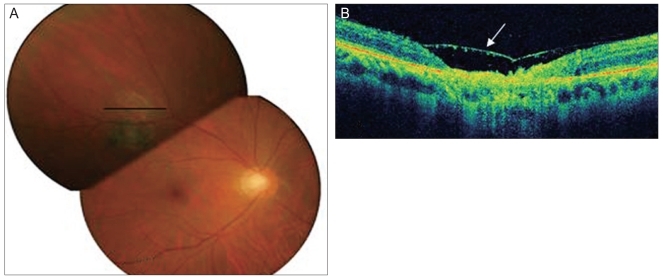

Fig. 3.

(A) The lesion resolved and had a scar-like appearance. (B) Spectral domain optical coherence tomography showed thinning of the retina, loss of normal striations, and a disorganized retinal pigment epithelium layer in addition to posterior hyaloid detachment (arrow).

Discussion

The diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis is most often based on the presence of characteristic clinical findings, which include focal retinochoroiditis, an adjacent or nearby retinochoroidal scar, and moderate to severe vitreous inflammation [3]. OCT is a noninvasive imaging modality that provides high-resolution, cross-sectional images of the retina. The recent introduction of SD-OCT has enabled imaging with greater resolution, higher scan speed, wider sampling area, and improved image registration [4]. Typical OCT findings of ocular toxoplasmosis include increased intraretinal reflectivity corresponding to the area of retinitis with shadowing of the underlying choroidal tissue. Posterior hyaloid thickening and detachment over the lesion and contained irregular hyperreflective formation are also typical [5].

Here we reported a case of ocular toxoplasmosis with abnormal thinning of the neurosensory retina, disrupted RPE and posterior hyaloid detachment in the lesion on SD-OCT. The posterior hyaloid was markedly thickened and exhibited irregular hyperreflectivity. SD-OCT also showed the loss of normal intraretinal striations in the areas of retinitis and the epiretinal membrane in detail. These features were detected SD-OCT than time domain OCT. Moreover, SD-OCT allowed ireal-time imaging of these manifestations in three dimensions (3D). Specifically, 3D imaging allows for unique perspectives of the retina, including qualitative assessments, such as membrane traction, to be performed and incorporated into clinical decision-making. The use of SD-OCT is helpful for definitively differentiating ocular toxoplasmosis from other retinal diseases and may provide insight for understanding the pathophysiologic mechanisms of ocular toxoplasmosis. Furthermore, SD-OCT allows for the detection of detailed pathologic changes that occur during treatment and precludes the need to perform biopsies.

Footnotes

No potential conflict of interest relevant to this article was reported.

References

- 1.McCannel CA, Holland GN, Helm CJ, et al. UCLA Community-Based Uveitis Study Group. Causes of uveitis in the general practice of ophthalmology. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121:35–46. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(14)70532-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pierce EA, D'amico DJ. Ocular toxoplasmosis: pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management. Semin Ophthalmol. 1993;8:40–52. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Smith JR, Cunningham ET., Jr Atypical presentations of ocular toxoplasmosis. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13:387–392. doi: 10.1097/00055735-200212000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Singh M, Chee CK. Spectral domain optical coherence tomography imaging of retinal diseases in Singapore. Ophthalmic Surg Lasers Imaging. 2009;40:336–341. doi: 10.3928/15428877-20090430-23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Orefice JL, Costa RA, Orefice F, et al. Vitreoretinal morphology in active ocular toxoplasmosis: a prospective study by optical coherence tomography. Br J Ophthalmol. 2007;91:773–780. doi: 10.1136/bjo.2006.108068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]