Abstract

Sleep is involved in the regulation of major organ functions in the human body, and disruption of sleep potentially can elicit organ dysfunction. Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most prevalent sleep disorder of breathing in adults and children, and its manifestations reflect the interactions between intermittent hypoxia, intermittent hypercapnia, increased intra-thoracic pressure swings, and sleep fragmentation, as elicited by the episodic changes in upper airway resistance during sleep. The sympathetic nervous system is an important modulator of the cardiovascular, immune, endocrine and metabolic systems, and alterations in autonomic activity may lead to metabolic imbalance and organ dysfunction. Here we review how OSA and its constitutive components can lead to perturbation of the autonomic nervous system in general, and to altered regulation of catecholamines, both of which then playing an important role in some of the mechanisms underlying OSA-induced morbidities.

Keywords: obstructive sleep apnea, autonomic nervous system, catecholamines, sympathetic, vagal, parasympathetic

Introduction

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is the most prevalent form of sleep disordered breathing. It has been estimated that 2–4% of the adult population in western countries suffer from clinically significant OSA (Young et al., 2002), and in children the prevalence is estimated to be between 1 and 3%, although considerable variation exists, most likely reflecting the absence of large-scale epidemiological studies with accurate phenotype assessments (Newacheck and Taylor, 1992; Guilleminault et al., 2005; Lumeng and Chervin, 2008). In recent years, OSA is becoming increasingly more prevalent as the average body weight of the pediatric population is rising (Tauman and Gozal, 2006).

Obstructive sleep apnea is characterized by repetitive collapse or near collapse of the upper airway during sleep, and these repetitive events impose substantial adverse effects on multiple organ systems in both adults and children, thereby emphasizing the importance of improving our understanding on the underlying pathophysiology of this disorder. As a result of these mechanical changes in the airway, hypoxemia, and hypercapnia develop, which further stimulate respiratory effort (Owens et al., 2008). However, without airway opening the increased drive is ineffective at increasing ventilation, such that generally, albeit not always, the apnea/hypopnea typically continues until the patient arouses from sleep and terminates the obstruction. After airway reopening, hyperventilation occurs to reverse the blood gas disturbances that developed during the respiratory event (Eckert et al., 2009). The repetitive nature of these apneas and the arousal events results in significant sleep fragmentation and promote excessive daytime sleepiness (Stepanski, 2002), fatigue, neurocognitive dysfunction, and increased cardiovascular morbidity (Kim et al., 2011).

Increased intra-thoracic pressure swings are an important component of OSA, and increased negative inspiratory intra-thoracic pressures generated against the occluded pharynx increase the left ventricular (LV) transmural pressures, and hence augment the LV afterload. These changes also increase venous return, augmenting right ventricular (RV) pre-load, whereas OSA-induced hypoxia will result in pulmonary vasoconstriction, therefore leading to increases in RV afterload. Taken together, RV distension, impairment of LV filling, and increased sympathetic activity will occur, and can synergistically increase myocardial oxygen demand in a contextual setting in which apnea-related hypoxia will reduce tissue oxygen delivery (Kasai and Bradley, 2011). Upon arousal from sleep, sympathetic activity, blood pressure, cardiac output, and heart rate rapidly increase, resulting in more increased cardiac oxygen demand at a time when arterial oxygen saturation is at its lowest level (Eckert et al., 2009). This can precipitate more severe myocardial ischemia and impair cardiac contractility and diastolic relaxation. Over time, such stresses may contribute to development or progression of cardiac remodeling, hypertrophy, and failure, while also prescribe an array of changes that may adversely impact the vasculature.

Based on aforementioned alterations as induced by OSA, it becomes apparent that the autonomic nervous system (ANS) activity is likely to play important pathophysiological roles. Therefore, the major aim of the current paper is to review the alterations in ANS activity and catecholaminergic systems in the context of sleep apnea. The ANS of mammals is involved with involuntary movements, actions, and organ functioning. This system can be further subdivided into the sympathetic motor system which is involved with quick responses, and the parasympathetic motor system which is involved with slower relaxing responses. Sympathetic stimulation may result in excitatory, dilatory, and inhibitory effects on vessels, muscles, and organs. Consequently, a large body of research has been conducted to understand the autonomic alterations that occur with the transition from waking to sleep, and throughout sleep state dynamics. During normal sleep there are changes in sympathetic nerve activity (SNA) that are tightly regulated by sleep state distribution. Indeed, SNA, blood pressure, and heart rate are lower in normal subjects while they are in deep non-REM (NREM) sleep than when awake, and during rapid eye movement (REM) sleep SNA increases above the levels recorded during wakefulness, even though blood pressure and heart rate return to the same levels recorded during wakefulness (Hornyak et al., 1991; Somers et al., 1993a).

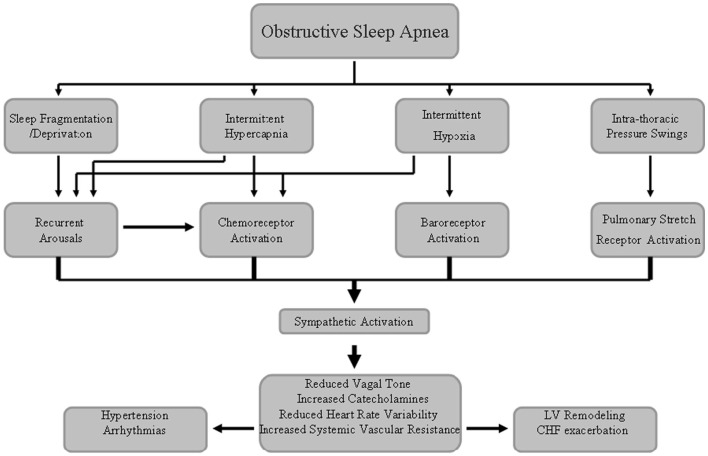

In OSA patients, the repetitive respiratory events lead to intermittent hypoxia (IH) and CO2 retention, both of which can augment SNA via stimulation of central and peripheral chemoreceptors (Somers et al., 1989a). Carotid sinus baroreceptors will also augment SNA coincident with the time in which they are being unloaded, because of the reduction in blood pressure and stroke volume during obstructive apneic events. Apnea also enhances SNA by eliminating reflex inhibition of SNA arising from pulmonary stretch receptors (Somers et al., 1989b). Sleep fragmentation and arousals from sleep at apnea termination also augment SNA and reduce cardiac vagal activity, although spontaneous arousals per se are associated with acute increases in SNA along with decreases in parasympathetic activity, which can precipitate post-apneic surges in blood pressure and heart rate (Horner et al., 1995, p. 67; Figure 1). These adverse autonomic effects induced by OSA may persist even during waking hours (Spaak et al., 2005; Kasai and Bradley, 2011).

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram underlying the sympathetic nerve system activation associated with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome that may lead to increased cardiovascular disease risk.

Catecholamine Production and Sympathetic Activation

Catecholamines (CAs; e.g., norepinephrine and epinephrine) are key hormones that prepare the body for one of its most primeval reactions: the “fight or flight” response. CAs increases the contractility and conduction velocity of cardiomyocytes, leading to increased cardiac output and a rise in blood pressure. Moreover, they facilitate breathing by bronchodilation, and urge the production of vital energy by mobilizing the body’s metabolic reserves (lipolysis and glycogenolysis). Past concepts held that the adrenal medulla and the postganglionic fibers in the sympathetic nervous system were the only systems responsible for the production, storage, and release of CAs. More recent findings suggest that phagocytic cells, lymphocytes (Flierl et al., 2008), and adipocytes (Vargovic et al., 2011) can also synthesize and release CAs. Because the brain and the immune system are some of the major adaptive systems, and communicate with each other extensively in an attempt to regulate body homeostasis, a common “language” is needed to facilitate this crosstalk. Key systems involved in this crosstalk are the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis and the ANS, consisting of the adrenergic sympathetic nervous system, the vagus-mediated parasympathetic nervous system, and the enteric nervous system (Elenkov et al., 2000).

The synthesis of CAs relies on tyrosine and the activity of two key enzymes, namely tyrosine hydroxylase (TH), which is known to be the rate-limiting step in catecholamine synthesis, and dopamine β-hydroxylase (DBH), which converts dopamine to norepinephrine (Elenkov et al., 2000). The catecholamine neurotransmitters are dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine. Although both norepinephrine and the methylated derivative epinephrine are stored in synaptic vesicles of neurons, epinephrine is not a neuromediator at the postganglionic sympathetic endings, with norepinephrine constituting the principal neurotransmitter of sympathetic postganglionic endings.

Tyrosine is transported into catecholamine-secreting neurons and adrenal medullary cells where catecholamine synthesis takes place. The first step in the process requires TH with tetrahydrobiopterin (H4B) as cofactor. The hydroxylation reaction generates DOPA (3,4-dihydrophenylalanine). DOPA decarboxylase converts DOPA to dopamine, dopamine β-hydroxylase converts dopamine to norepinephrine and phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase converts norepinephrine to epinephrine. Within the substantia nigra and some other regions of the brain, synthesis proceeds only to dopamine. Within the adrenal medulla, dopamine is converted to norepinephrine and epinephrine (Hui et al., 2003). Once synthesized, dopamine, norepinephrine, and epinephrine are packaged in granulated vesicles. Within these vesicles, norepinephrine and epinephrine are bound to ATP and chromogranin A.

The actions of norepinephrine and epinephrine are exerted via receptor-mediated signal transduction events. There are three distinct types of adrenergic receptors: α1, α2, and β, with each including several sub-classes that exhibit different activity depending on the receptor in the target organ. Dopamine binds to dopaminergic receptors identified as D-type receptors and there are four sub-classes identified as D1, D2, D4, and D5. Activation of the dopaminergic receptors results in activation of adenylate cyclase (D1 and D5) or inhibition of adenylate cyclase (D2 and D4). In response to stress stimuli such as fear, pain, extreme temperatures, hypoxia, or hypotension, CAs are released directly into the circulation, activating peripheral adrenergic receptors with subsequent chronotropic and inotropic effects on the heart, redistribution of blood flow to organs and muscles, and release of energy through glycolysis and lipolysis. This systemic effect also includes sensitizing certain receptors to subsequent sympathetic or somatic nerve stimulation, along with concomitant inhibition of pain sensation, thus facilitating the coordinated responses that characterize the “fight or flight” situation (Smith et al., 1998).

Assessment of Autonomic Function and Normal Sleep Physiology

Direct measurements of autonomic activity, particularly during sleep, are not an easy task, and require invasive approaches. Consequently, the vast majority of such studies have been conducted using animal models. However, recent technological advances have enabled direct measurements of sympathetic activity to be performed for extended periods of time in human muscle. Furthermore, surrogate markers of ANS activity such as linear and non-linear dynamic analyses of heart rate variability (HRV), peripheral arterial tonometry (PAT), continuous beat-to-beat blood pressure monitoring, non-invasive radionuclide imaging, or quantitation of serum and urine catecholamines and their metabolic products have emerged as useful markers of changes in ANS, thereby permitting more extensive probing of the autonomic system in health and disease (Smith et al., 1998).

Sleep is involved in the regulation of peripheral organ function, such as endocrine and cardiovascular function, and specific changes in peripheral organ systems occur during both REM and non-REM (NREM) components of sleep in healthy individuals. One well established sleep-associated cardiovascular change is the decrease in blood pressure and heart rate that occurs during sleep in a variety of species, a phenomenon generally referred to as “blood pressure dipping” (Antic et al., 2001). The sleep-related decrease in blood pressure occurs in addition to the blood pressure changes induced by the circadian clock and changes in body posture that typically accompany sleeping behaviors. Blood pressure dipping is contingent upon a reduction in global sympathetic tone activity (reflecting increased parasympathetic tone along with sympathetic withdrawal) as non-dippers exhibit an increase in sympathetic tone at sleep onset (Ziegler, 2003). Sleep state transitions are also accompanied by other changes in the cardiovascular system, for example, when transitioning from NREM sleep to REM sleep, blood pressure, and heart rate typically increase and become more unstable (Schwimmer et al., 2010). These phenomena are altered in OSA patients, and are believed to underlie the increased risk for development of hypertension, one of the important cardiovascular morbidities of the disorder.

Rodent Models of OSA and Autonomic Function

The manifestations of OSA reflect the interactions of IH, intermittent hypercapnia, increased intra-thoracic pressure swings, and sleep fragmentation, as elicited by the episodic changes in upper airway resistance during sleep. Data from clinical studies and animal models, particularly those reflecting exposures to IH, have revealed the induction of sympathetic nerve stimulation leading to vasoconstriction and hypertension, whereby both baro- and chemoreceptors activity and regulation are involved in the sympathetic control of blood pressure (Guyenet, 2006). The baroreflex provides a negative feedback loop in which elevated blood pressure inhibits sympathetic outflow, decreases heart rate, and, thus, lowers blood pressure. In a similar fashion, decreased blood pressure activates baroreflex mechanisms, causing heart rate increases, and blood pressure to rise (Golbidi et al., 2011). Attenuated baroreceptor sensitivity is proposed to lead to increased sympathetic activation. In a recent review, Prabhakar and Kumar (2010) concluded that patients with OSA do exhibit a reduction in baroreflex sensitivity, as evidenced by attenuated heart rate and vascular resistance responses to baroreceptor activation, and that restoration of baroreflex sensitivity will occur after treatment with CPAP (Carlson et al., 1993; Bonsignore et al., 2006; Monahan et al., 2006; Cooper et al., 2007). Similarly, when rodents were exposed to IH, attenuated baroreflex function, sensitivity and activity, or changes in the reflex set point depending on the severity of the hypoxia stimulus developed over time (Brooks et al., 1999; Greenberg et al., 1999; Lai et al., 2006; Gu et al., 2007; Peng et al., 2012). These changes also led to exaggerated sympathetic activity and eventually elicited elevations of blood pressure and the elimination of the normal blood pressure dipping during sleep.

On the other hand, the arterial chemoreceptors, especially the carotid bodies which operate as the primary sensors for hypoxia and the ensuing carotid chemoreflex will activate SNA, elevate blood pressure, and stimulate breathing (Prabhakar and Kumar, 2010). Since the introduction of a rodent IH model by Fletcher et al. (1992), augmented chemoreflex-stimulated sympathetic outflow was clearly identified (Bao et al., 1997), and found to be mediated via the renin–angiotensin system and also via the modulation of oxygen-sensing in carotid bodies by activation of Hypoxia Inducible Factor-1 (HIF-1) and down regulation of HIF-2, as well as via changes in oxidative stress activity (La Rovere et al., 1998; Fletcher et al., 2002; Peng et al., 2003; Prabhakar et al., 2009). Furthermore, stimulation of carotid bodies by IH is also associated with a reduction in baroreflex sensitivity in cats (Rey et al., 2004), rats (Soukhova-O’Hare et al., 2006a; Gu et al., 2007; Lin et al., 2008; Yan et al., 2008, 2009), and mice (Lin et al., 2007). These effects of chronic IH on carotid body function and sensitivity are reversed completely after re-exposure to normoxia in adult subjects (Peng et al., 2003), but not if IH exposures occur during a critical period of postnatal development (Soukhova-O’Hare et al., 2006b, 2008).

The reversible nature of the carotid body responses to chronic IH in adults could explain why CPAP therapy reverses some of the adverse cardio-sympathetic effects in OSA patients (Prabhakar and Kumar, 2010). Exposure of mice to more than 30 days of IH elicited elevated systemic blood pressure that persisted even during normoxia, along with enhanced sympathoadrenal activity as measured by catecholamine levels, especially norepinephrine. Surgical denervation of peripheral chemoreceptors or adrenal demedulation and chemical denervation of the peripheral sympathetic nervous system prevented the increase in arterial blood pressure (Lesske et al., 1997; Dematteis et al., 2008; Gonzalez-Martin et al., 2009). A more recent study by Gonzalez-Martin et al., 2011), who exposed rats to 15 days of IH, concluded that IH leads to a bias in the integration of the inputs arising from the carotid body characterized by a diminished drive of ventilation along with an exaggerated activation of brainstem sympathetic neurons. In conclusion, chronic IH selectively augments the carotid body sensitivity to hypoxia resulting in a long lasting activation of chemosensory inputs to the medial and commissural nuclei of the solitary tract (Prabhakar et al., 2001; Kara et al., 2003). In parallel, extensive changes occur in central neural regions governing autonomic system nervous system outflow and other integrated outputs such as respiration (Ai et al., 2009). These changes notwithstanding, a multiplicity of interactions and additional mechanisms are likely involved and are dependent on the age at which IH occurs, the severity, cycle duration, and overall duration of IH, and the association of additional perturbations such as hypercapnia or hypocapnia (Waters and Gozal, 2003; Reeves et al., 2006; Mahamed and Mitchell, 2008; Iturriaga et al., 2009; Zoccal et al., 2009; Kline, 2010; Xing and Pilowsky, 2010; Baker-Herman and Strey, 2011; Dodig et al., 2011; Molkov et al., 2011; Prabha et al., 2011).

A characteristic feature of mammalian sleep is decreased postural muscle tone, especially during REM sleep. The suppression of motor activity also involves respiratory muscles, particularly in those that combine postural and respiratory functions, such as the intercostal and pharyngeal muscles; this effect of REM sleep is modulated by catecholamine secretion. The genioglossus muscle, an important upper airway dilator is innervated by the hypoglossal motoneuron, and both norepinephrine and serotonin lead to excitation of orofacial motoneurons, including those that innervate upper airway muscles, and both noradrenergic (NE) and serotonergic brainstem neurons have been shown in animal models to reduce their activity during slow-wave sleep and stop firing during REM sleep (Aston-Jones and Bloom, 1981; Kubin et al., 1998; Fenik et al., 2005; Rukhadze and Kubin, 2007). These data suggest that sleep-related withdrawal of aminergic excitation may cause decrements of motoneuronal activity, thereby contributing to sleep-related upper airway hypotonia. Chan and colleagues have confirmed this hypothesis in rats, and identified an endogenous noradrenergic drive that contributes to the genioglossus muscle activity. Furthermore, withdrawal of the excitation is mediated by alpha1-adrenergic receptors, which play a major role of sleep-related suppression of activity in hypoglossal motoneurons (Chan et al., 2006).

Recurrent arousals in the context of OSA lead to sleep fragmentation and are associated with state-related increases in the sympathetic activity to peripheral arteries, that in turn may lead to large repetitive blood pressure rises that can be as high as 60–80 mmHg. These oscillations in blood pressure are thought to be important risk factors in the development of vascular events (Bao et al., 1999; Kohler and Stradling, 2010). Horner et al. (1995) studied tracheostomized dogs and showed that arousals from sleep are associated with marked increases in heart rate that can be attenuated by sympathetic blockade. Evidence for alterations in the sympathetic activity that accompanies sleep fragmentation include increased levels of cortisol, epinephrine, and norepinephrine along with increased heart rate and systolic blood pressure (Andersen et al., 2004, 2005; Everson and Crowley, 2004; Perry et al., 2007; Tartar et al., 2009).

Autonomic Alterations in Adult Patients with OSA

In combination with other co-factors, sympathetic and catecholaminergic alterations are believed to play an important role in the pathophysiology of the cardiovascular morbidity in adults with OSA (see Table 1 for summary). The cumulative evidence that has emerged in the last three decades using multiple methods to quantify sympathetic activity in patients with OSA supports this putative association. Indeed, OSA patients demonstrate a reduction in vagal modulation of HRV in comparison with controls (Aydin et al., 2004; Kesek et al., 2009; Bianchi et al., 2010; Balachandran et al., 2012), and such alterations in cardiac sympathetic and parasympathetic modulation are improved after treatment with either CPAP or upper airway surgery (Cheng et al., 2011; Choi et al., 2011; Gapelyuk et al., 2011). However, we should acknowledge that although HRV measurements provide non-invasive probes into ANS function, they are fraught with substantial limitations (Poupard et al., 2011), such that alternative methods have been used. However, discussion of the pros and cons of such methodologies is clearly beyond the scope of this review.

Table 1.

Summary of autonomic nervous system alterations in adult OSA patients.

| Modality | Reference | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure | Bixler et al. (2000), Suzuki et al. (1996), Borgel et al. (2004), Heitmann et al. (2004), Dhillon et al. (2005), Pepperell et al. (2002), Faccenda et al. (2001), Dernaika et al. (2009), Robinson et al. (2008), Patruno et al. (2007), Wilcox et al. (1993), Hui et al. (2006), Duran-Cantolla et al. (2010), Marrone et al. (2011) | OSA is associated with elevated blood pressure that is attenuated by CPAP therapy; differences emerge regarding the level of reduction in BP after treatment, the circadian time at which reduction occurs (sleep/wakefulness), and whether the systolic or diastolic component is more affected |

| Urine and blood catecholamine levels | Fletcher et al. (1987), Baruzzi et al. (1991), Ziegler et al. (1997), Minemura et al. (1998), Loredo et al. (1999), Elmasry et al. (2002), Sukegawa et al. (2005), Drager et al. (2007), Kohler et al. (2008), Comondore et al. (2009), Zhang et al. (2011), Bao et al. (2002), Ziegler et al. (2001), Kohler et al. (2011) | OSA patients demonstrate sustained elevation in catecholamine levels that are attenuated by treatment, and are elevated again by treatment withdrawal. Hypertensive patients will experience a larger reduction in catecholamine levels |

| Muscle synaptic nerve activity (MSNA) | Imadojemu et al. (2007), Usui et al. (2005), Narkiewicz et al. (1999a), Gilmartin et al. (2008, 2010), Xie et al. (1999), Morgan et al. (1996) | Higher basal MSNA in OSA patients, which is attenuated with treatment |

| Heart rate variability (HRV) | Balachandran et al. (2012), Bianchi et al. (2010), Aydin et al. (2004), Kesek et al. (2009), Choi et al. (2011), Cheng et al. (2011), Gapelyuk et al. (2011) | Reduced HRV is found in OSA patients, and is improved after treatment with CPAP or upper airway surgery |

Hypertension is one of the leading cardiovascular morbidities of OSA, and enhanced sympathetic activity is believed to play a fundamental role in the blood pressure elevation. Thus, beat-to-beat monitoring of blood pressure changes has been used to assess changes in sympathetic activity in OSA patients. In general, OSA patients all levels of severity demonstrate increases in both systolic and diastolic blood pressure during sleep and wakefulness (Table1; Kohler et al., 2008). Furthermore, high blood pressure in the context of OSA was resistant to conventional anti-hypertensive drug therapy (Pedrosa et al., 2011), with in some instances resembling pheochromocytoma, with catecholamine surges and malignant hypertension becoming manifest (Cheezum and Lettieri, 2010). Although a large group of studies have demonstrated that blood pressure elevations were attenuated by treatment of OSA (Weiss et al., 2007; Friedman and Logan, 2009; Table 1), the changes in blood pressure have traditionally been modest (Duran-Cantolla et al., 2010), even if the strength of the association may apply only to selected subsets of the general population (Cano-Pumarega et al., 2011). Indeed, there are reported differences regarding the reduction in systolic and diastolic components of blood pressure, with only daytime diastolic blood pressure being affected by treatment in some studies, and with both systolic and diastolic values being favorably reduced during sleep in other studies (Voogel et al., 1999; Norman et al., 2006; Marrone et al., 2011), or during daytime (Wilcox et al., 1993; Ip et al., 2004). Furthermore, only systolic blood pressure was reduced during the night after treatment in yet other studies (Suzuki et al., 1993). These differences in the response to therapy can be attributed to a large number of confounders such as ethnicity, gender, age, presence of underlying diseases, as well as genetic polymorphisms. It is possible that the more favorable reduction in diastolic blood pressure reflects its dependency on arteriolar tone, which is highly influenced by sympathetic activity, the latter being high in patients with OSA both during wakefulness and during sleep (Marrone et al., 2011).

Because of the unique roles that catecholamines play in the transduction of sympathetic activity, multiple studies have assessed their concentrations, and shown the presence of elevated levels of catecholamines in both urine and plasma among patients with OSA. Some of these studies also showed that catecholamine levels were attenuated after treatment, thereby leading to the proposition that catecholamines levels may serve as a surrogate biomarker for OSA (Fletcher et al., 1987; Baruzzi et al., 1991; Ziegler et al., 1997; Minemura et al., 1998; Loredo et al., 1999; Elmasry et al., 2002; Sukegawa et al., 2005; Drager et al., 2007; Kohler et al., 2008; Comondore et al., 2009; Zhang et al., 2011). However, data emerging from clinical trials has revealed substantial variability regarding CPAP treatment and its effects on catecholamines levels, with some reporting a reduction in circulating catecholamines that extended into daytime and wakefulness, while others did not find any effect of CPAP treatment on catecholamine concentrations (Ziegler et al., 2001; Bao et al., 2002; Comondore et al., 2009). These discrepancies are probably and partially explained by the fact that the therapeutic effect of CPAP on blood pressure and sympathetic outflow is more prominent in hypertensive patients when compared to normotensive OSA patients (Heitmann et al., 2004). Mills et al. (2006) assessed the effect of CPAP therapy on norepinephrine kinetics, and found that CPAP treatment in OSA patients leads to a reduction in renal sympathetic neural activity by enhancing the renal clearance of norepinephrine rather than by attenuating norepinephrine synthesis rates. Another important observation was recently reported by Kohler and coworkers who studied the effect of CPAP withdrawal in patients with OSA. These investigators showed that CPAP withdrawal was not only accompanied by rapid recurrence of OSA symptoms, return of subjective sleepiness, impaired endothelial function, and increases in blood pressure and heart rate, but also by elevation in urinary catecholamines (Kohler et al., 2011). Altogether, these studies seem to support the assumption that OSA patients sustain elevations in catecholamine levels that are attenuated by treatment, and are elevated again by treatment withdrawal. These observations would make it plausible to consider catecholamine levels in the blood or urine as a potentially viable biomarker of OSA severity that can be used to monitor patients responses to treatment (Comondore et al., 2009; Tasali et al., 2011). However, the role of catecholamine levels as a valid biomarker for diagnosis of OSA is not firmly established, most likely because of the large amount of confounding factors and associated morbidities that frequently accompany OSA and can independently lead to changes in catecholamine levels. Indeed, confounding factors such as age, hypertension, obesity, and the use of anti-hypertensive medications are not easy to control for, thereby increasing the difficulty to interpret at the individual patient level the real impact of OSA on catecholamine levels.

In addition to clinical trials aiming to define the contribution of each component of OSA to sympathetic activity, Foster et al. (2009) conducted an experimental randomized controlled study in humans in which they exposed 10 healthy men to 6 h/day of IH or sham (2 min cycles). After 4 days of IH, mean systemic blood pressure increased by 4 mmHg, and nitric oxide derivatives were reduced by 55%, the latter being associated with an increase in the pressor response and in cerebral vascular resistance to hypoxia (Foster et al., 2009). This study clearly supports previous findings demonstrating that hypoxemia elevates sympathetic nervous system tone and exaggerates sympathetic basal activity in patients with OSA (Leuenberger et al., 1995; Somers et al., 1995; Smith et al., 1996; Imadojemu et al., 2007). Gilmartin et al. (2008) measured changes in muscle sympathetic nerve activity (MSNA) in subjects exposed to chronic sustained nocturnal hypoxia and found an augmented MSNA and a rise in blood pressure after 14 nights of exposure. Recently, the same group (Gilmartin et al., 2010) confirmed these results in healthy subjects exposed to intermittent nocturnal hypoxia (9 h/night) for 28 days. These investigators found augmented MSNA with elevation of blood pressure after 2 weeks of exposure, which further increase after 4 weeks of IH. Using another aspect of MSNA measurements combined with electrocardiogram recordings and consisting of assessments of sympathetic burst latency in humans, several investigators (Morgan et al., 1996; Xie et al., 1999) have shown that arousal from sleep, regardless of whether it occurs spontaneously or is evoked by an apnea, consistently elicits reductions in sympathetic burst latency. These observations may reflect a temporary diminution of the baroreflex buffering of sympathetic outflow, and may play an important role in the cardiovascular morbidity induced by repetitive arousals from sleep. Data from studies comparing OSA patients to controls show a higher basal MSNA level in OSA patients, and also exaggerated MSNA responses to hypoxia, with treatment with CPAP attenuating both basal MSNA and hypoxic MSNA responses. Thus, arterial chemoreflex sensitivity is increased in OSA and can be reversed by treatment (Narkiewicz et al., 1999b; Usui et al., 2005; Imadojemu et al., 2007).

As mentioned above, repetitive arousals are not only an important component of OSA, but are also associated with state-related increases in the sympathetic activity to peripheral arteries (Loredo et al., 1999), which will usually lead to large repetitive blood pressure rises as high as 60–80 mmHg (Somers et al., 1989a). In an experimental study of nine healthy humans, intra-thoracic pressure changes induced by the Mueller maneuver were associated with oscillations in blood pressure and increased SNA. This is somewhat different from the time sequence of changes in obstructive apnea, whereby SNA is initially increased, and the blood pressure elevation usually occurs later at the end of the apnea (Somers et al., 1993b). Experimental paradigms of sleep disruption have demonstrated that sleep perturbations alone may play an important role in the autonomic changes leading to the cardiovascular morbidity observed in OSA. Leiter et al. (1985) studied 11 men and showed that a single night of sleep deprivation decreases upper airway dilator muscle activity during hypercapnic rebreathing, a response that may predispose to upper airway collapse. In fact, loss of sleep is associated with reduced ventilatory responses to hypercapnia and hypoxia, a response that potentially can deteriorate respiratory performance to airway obstruction (White et al., 1983). It is possible that such changes in upper airway dynamics may reflect altered ANS outputs to upper airway as discussed above.

In summary, increases in sympathetic activity during sleep may be explained by the repetitive apneic events and their integral constitutive elements. Remarkably, high sympathetic drive is present even during daytime wakefulness, at a time that no respiratory disturbances occur, and when both arterial oxygen saturation and carbon dioxide levels are normal (Narkiewicz and Somers, 2003).

Autonomic Alterations in Children with OSA

For many years, the prevailing assumption was that children were somewhat protected from any cardiovascular morbidity with pediatric OSA due to the redundancy of protective mechanisms, and the increased vascular capacitance and reserve in children (see Table 2 for summary). However, such assumptions have been disproven in the last 15 years since the publication of initial papers by Aljadeff et al. (1997) showing altered ANS function and by Marcus et al. (1998) showing that elevations in blood pressure did occur in children with relatively severe OSA.

Table 2.

Summary of autonomic nervous system alterations in children with OSA.

| Modality | Reference | Effect |

|---|---|---|

| Blood pressure monitoring | Marcus et al. (1998), O’Driscoll et al. (2009a,b), Kohyama et al. (2003), Leung et al. (2006), Bixler et al. (2008), Amin et al. (2004) | Arterial blood pressure was increased in OSA children and more pronounced during NREM sleep and during arousals |

| Urine and blood catecholamines | Snow et al. (2010), Kaditis et al. (2009), Oliveira et al. (2010), Kelly et al. (2010), O’Driscoll et al. (2011), Nakra et al. (2008) | OSA patients exhibit severity-dependent elevations in catecholamine levels which respond to treatment |

| Heart rate variability (HRV) | Aljadeff et al. (1997), Baharav et al. (1999), Constantin et al. (2008), Muzumdar et al. (2011) | OSA alters cardiac beat-to-beat variation that is most prominent during slow heart rates. Improvements in HRV occur after treatment |

| Peripheral arterial tonometry (PAT), pulse transit time (PTT) | O’Brien and Gozal (2005, 2007), Tauman et al. (2004), Katz et al. (2003), Pillar et al. (2002), Brietzke et al. (2007), Foo et al. (2006), Pepin et al. (2005), Paruthi and Chervin (2010) | Exaggerated sympathetic responses following vital capacity sighs and ice-cold hand pressor tests. Unique PTT signatures appear to be present in pediatric OSA |

The mechanisms underlying cardiovascular morbidities in children most probably closely overlap the mechanisms leading to such morbidity in adults. In a series of studies over the last decade, our laboratory has shown that the combination of IH, sleep fragmentation, episodic hypercapnia, and increased intra-thoracic pressure swings, can separately and in conjunction activate or amplify the onset and propagation of endothelial dysfunction, atherogenesis, increased systemic inflammation, oxidative stress, and activation of adhesion molecules and coagulation (Parish and Somers, 2004; Gozal et al., 2007; Gozal and Kheirandish-Gozal, 2008; Kim et al., 2011) in parallel with the important process of sustained activation of the sympathetic nervous system (Somers et al., 1995). Furthermore, we have provided initial evidence that the alterations in ANS function may be reflected by the presence of either increased sympathetic nervous system tone, increased responsiveness, or the emergence of sympathetic–parasympathetic imbalance (Bhattacharjee et al., 2009).

Studies exploring alterations in autonomic function in children with sleep disordered breathing are relatively sparse, particularly because of the difficulties associated with invasive assessments such as nerve recordings (Narkiewicz and Somers, 2003). Therefore, all studies have resorted to non-invasive probing of the ANS. Aljadeff et al. (1997) used HRV analyses including both linear and non-linear dynamic analyses and Poincare scatter plots, and showed the presence of substantial alterations in sympathetic tone in children with OSAS. Similar findings were subsequently reported using power spectral analysis of heart rate (Baharav et al., 1999), whereby a sympathetic predominance during REM sleep emerged in pediatric OSA patients. O’Brien and Gozal (2005) measured sympathetic responses during wakefulness in 28 children with sleep disordered breathing and in 29 healthy controls using PAT, and demonstrated exaggerated sympathetic responses following vital capacity sighs and ice-cold hand pressor tests in the OSA group, thereby providing compelling evidence on the presence of increased sympathetic reactivity during wakefulness in children with OSA. Other studies using heart rate dynamics have also suggested that sleep state and OSA are important determinants of cardiac autonomic outflow that can be readily assessed with these methods and potentially provide a diagnostic algorithm (Shouldice et al., 2004; Deng et al., 2006). A reduction of the increased HR variability during sleep after treatment was initially reported with adenotonsillectomy in OSA children (Constantin et al., 2008), and subsequently confirmed (Muzumdar et al., 2011).In another study that included 25 children (mean age 10.2 ± 2.3 years) undergoing a diagnostic assessment for OSA, and 25 age-matched healthy control subjects, all participants underwent an overnight polysomnography and were subjected to autonomic cardiovascular tests for the assessment of autonomic function (head-up tilt test, Valsalva maneuver, and deep breathing test). Increased basal sympathetic activity during wakefulness and also impaired severity-dependent responses to the autonomic challenges emerged (Montesano et al., 2010). Of note, periodic arousals even when induced by non-respiratory events can also trigger alterations in autonomic function in children (Walter et al., 2009).

Another frequently used non-invasive tool for assessment of changes in ANS tone is the measurement of pulse transit time (PTT). Indeed, PTT may serve as yet another indicator of sympathetic burst activity by measuring the delay from the initial LV electrical depolarization in the electrocardiogram to the appearance of the corresponding plethysmographic signal of the oximetry waveform at the wrist (Foo and Lim, 2006). In studies conducted in healthy children in whom recordings of PAT and PTT were simultaneously performed, it became apparent that arousals were associated with predictable changes in both PAT and PTT, thereby linking sympathetic discharges to non-invasive measures in children (Pillar et al., 2002; Katz et al., 2003; Tauman et al., 2004; O’Brien and Gozal, 2007). These findings further suggested PTT as a potentially valuable diagnostic screening tool for OSA and as a probe of sympathetic activity changes (Pepin et al., 2005; Foo et al., 2006; Brietzke et al., 2007; Paruthi and Chervin, 2010).

In an effort to obtain more accurate correlates of sympathetic activation in children, measurements of the concentrations of catecholamines in plasma or urine specimens have also been explored in pediatric OSA patients. Kaditis et al. (2009) measured urinary catecholamines in 44 OSA children with different levels of nocturnal hypoxemia, and also included 10 control children. Noradrenaline and adrenaline urine levels correlated significantly with the obstructive apnea–hypopnea index. Since concentrations of catecholamines were measured in morning urine specimens collected after arousal from sleep, the significant associations between urinary catecholamines and polysomnographic indices most likely reflect increased nocturnal activity of sympathetic neurons and possibly of the adrenal medulla (Kaditis et al., 2009). In a larger cohort, Snow et al. (2010) assessed 159 habitually snoring children who underwent overnight polysomnography and collection of the first morning voided urine sample to measure the concentrations of norepinephrine, epinephrine, and dopamine. In a subset of children, blood samples were also drawn for gene expression of catecholamine-relevant genes. Children with OSA had significantly higher urinary norepinephrine and epinephrine levels, but not dopamine, compared to habitual snorers (norepinephrine: 40.1 ± 24.7 ng/mg creatinine vs. 31.6 ± 16.2 ng/mg creatinine, P < 0.01; epinephrine: 6.4 ± 10.5 ng/mg vs. 4.5 ± 0.5 ng/mg, P < 0.01). As previously shown by Kaditis et al. (2009), norepinephrine and epinephrine levels were significantly correlated with polysomnographic indices, but there was no evidence that body mass index contributed to this association (Snow et al., 2010). Thus, altered sympathetic activity in OSA patients appears to occur independently of the presence of obesity. In addition, Snow et al. (2010) also showed a higher gene expression among genes that are involved in the synthesis and transport of catecholamines, as well as in selected important receptors, with such findings suggesting the presence of increased bioavailability of catecholamines. More recently, several groups have confirmed that AHI is a significant independent predictor of noradrenaline and adrenaline levels (Kelly et al., 2010; Oliveira et al., 2010; O’Driscoll et al., 2011). In a different study, Nakra et al. (2008) assessed a small group of obese children and adolescents in whom norepinephrine levels were assessed hourly throughout the night before and after treatment with CPAP for 3 months. Catecholamine levels were reduced after treatment in this cohort, further confirming the effect of OSA on sympathetic outflow.

Alterations in blood pressure are one of the important morbidities linked to modifications in autonomic and sympathetic function in OSA. As mentioned above, Marcus et al. (1998) were the first to report alterations in systemic blood pressure in children. The potential reduction in baroreflex function that have been clearly identified in animal models have also been reported in children with OSA (McConnell et al., 2009). Accordingly, it is not surprising that a number of investigative groups have explored and reported the presence of systemic blood pressure alterations associated with OSA in pediatric population, with such changes being more pronounced during NREM sleep and also associated with arousals (Kohyama et al., 2003; Amin et al., 2004; Leung et al., 2006; Bixler et al., 2008; O’Driscoll et al., 2009a,b). Furthermore, severity-dependent alterations in LV function with decreased diastolic and systolic contractility have also been clearly identified in pediatric OSA (Amin et al., 2008; Ugur et al., 2008; Kaditis et al., 2010).

In the past decades, the prevalence of obesity and diabetes has greatly increased in industrialized countries, and both sleep curtailment and SDB are becoming recognized as contributing factors, alongside increased caloric intake, and decreased physical activity. The autonomic nerve system is an important regulator of metabolic function in major organs including the liver, adipose tissue, muscle, and pancreas, whereby alterations in autonomic function contribute to metabolic dysfunction and obesity (Enriori et al., 2011; Lambert et al., 2011; Straznicky et al., 2011). Since as discussed earlier, sleep disorders are strongly connected to autonomic dysfunction, the connection between sleep disturbances, autonomic alterations, and metabolic morbidities is becoming increasingly apparent (Spiegel et al., 2004; Trombetta et al., 2010).

Summary

Considering the close relationships between sleep regulatory mechanisms and autonomic nerve system function described heretofore, any sleep disturbance can theoretically lead to alterations in sympathetic activity, and may thus elicit metabolic and cardiovascular morbidities. Conclusive evidence has become available to indicate that OSA components lead to pathological activation of the sympathetic nervous system and contribute to the pathophysiology of high blood pressure, arrhythmias, and congestive heart failure in adults. In children, there is increasing data indicating that OSA can lead to changes in heart rate responses and elevated blood pressure. Importantly, OSA treatment using CPAP or upper airway surgical procedures will lead to attenuation of the heightened sympathetic activity, which in turn will lower blood pressure levels and reduce cardiovascular morbidities in adults and children. Thus, the importance of autonomic perturbations in the context of sleep disorders becomes apparent and can promote metabolic, cardiovascular, and psychological morbidities throughout life. Data from rodent studies further show that there are long-term implications to the autonomic nerve system perturbations that occur during developmental windows in infancy and childhood in response to OSA, particularly in the context of underlying genetic predisposing factors that govern cardiovascular and metabolic disease susceptibility (Vallee et al., 1996; Young, 2002; Van den Hove et al., 2006; Mastorci et al., 2009). In the clinical context, utilization of catecholamine levels as a potential biomarker for OSA in the context of diagnosis and adherence to therapy is intriguing and merits further validation.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Leila Kheirandish-Gozal is supported by NIH grant K12 HL-090003; David Gozal is supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL-065270 and HL-086662.

References

- Ai J., Wurster R. D., Harden S. W., Cheng Z. J. (2009). Vagal afferent innervation and remodeling in the aortic arch of young-adult Fischer 344 rats following chronic intermittent hypoxia. Neuroscience 164, 658–666 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2009.06.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aljadeff G., Gozal D., Schechtman V. L., Burrell B., Harper R. M., Ward S. L. (1997). Heart rate variability in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 20, 151–157 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin R., Somers V. K., Mcconnell K., Willging P., Myer C., Sherman M., Mcphail G., Morgenthal A., Fenchel M., Bean J., Kimball T., Daniels S. (2008). Activity-adjusted 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure and cardiac remodeling in children with sleep disordered breathing. Hypertension 51, 84–91 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.107.099762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amin R. S., Carroll J. L., Jeffries J. L., Grone C., Bean J. A., Chini B., Bokulic R., Daniels S. R. (2004). Twenty-four-hour ambulatory blood pressure in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 169, 950–956 10.1164/rccm.200309-1305OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen M. L., Martins P. J., D’Almeida V., Bignotto M., Tufik S. (2005). Endocrinological and catecholaminergic alterations during sleep deprivation and recovery in male rats. J. Sleep Res. 14, 83–90 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2004.00428.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen M. L., Martins P. J., D’Almeida V., Santos R. F., Bignotto M., Tufik S. (2004). Effects of paradoxical sleep deprivation on blood parameters associated with cardiovascular risk in aged rats. Exp. Gerontol. 39, 817–824 10.1016/j.exger.2003.10.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antic V., Van Vliet B. N., Montani J. P. (2001). Loss of nocturnal dipping of blood pressure and heart rate in obesity-induced hypertension in rabbits. Auton. Neurosci. 90, 152–157 10.1016/S1566-0702(01)00282-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aston-Jones G., Bloom F. E. (1981). Activity of norepinephrine-containing locus coeruleus neurons in behaving rats anticipates fluctuations in the sleep-waking cycle. J. Neurosci. 1, 876–886 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aydin M., Altin R., Ozeren A., Kart L., Bilge M., Unalacak M. (2004). Cardiac autonomic activity in obstructive sleep apnea: time-dependent and spectral analysis of heart rate variability using 24-hour Holter electrocardiograms. Tex. Heart Inst. J. 31, 132–136 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baharav A., Kotagal S., Rubin B. K., Pratt J., Akselrod S. (1999). Autonomic cardiovascular control in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Clin. Auton. Res. 9, 345–351 10.1007/BF02318382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker-Herman T. L., Strey K. A. (2011). Similarities and differences in mechanisms of phrenic and hypoglossal motor facilitation. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 179, 48–56 10.1016/j.resp.2011.06.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran J. S., Bakker J. P., Rahangdale S., Yim-Yeh S., Mietus J. E., Goldberger A. L., Malhotra A. (2012). Effect of mild, asymptomatic obstructive sleep apnea on daytime heart rate variability and impedance cardiography measurements. Am. J. Cardiol. 109, 140–145 10.1016/j.amjcard.2011.07.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao G., Metreveli N., Fletcher E. C. (1999). Acute and chronic blood pressure response to recurrent acoustic arousal in rats. Am. J. Hypertens. 12, 504–510 10.1016/S0895-7061(99)00032-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao G., Metreveli N., Li R., Taylor A., Fletcher E. C. (1997). Blood pressure response to chronic episodic hypoxia: role of the sympathetic nervous system. J. Appl. Physiol. 83, 95–101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao X., Nelesen R. A., Loredo J. S., Dimsdale J. E., Ziegler M. G. (2002). Blood pressure variability in obstructive sleep apnea: role of sympathetic nervous activity and effect of continuous positive airway pressure. Blood Press. Monit. 7, 301–307 10.1097/00126097-200212000-00002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baruzzi A., Riva R., Cirignotta F., Zucconi M., Cappelli M., Lugaresi E. (1991). Atrial natriuretic peptide and catecholamines in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 14, 83–86 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharjee R., Kheirandish-Gozal L., Pillar G., Gozal D. (2009). Cardiovascular complications of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: evidence from children. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 51, 416–433 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi A. M., Mendez M. O., Ferrario M., Ferini-Strambi L., Cerutti S. (2010). Long-term correlations and complexity analysis of the heart rate variability signal during sleep. Comparing normal and pathologic subjects. Methods Inf. Med. 49, 479–483 10.3414/ME09-02-0037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixler E. O., Vgontzas A. N., Lin H. M., Liao D., Calhoun S., Fedok F., Vlasic V., Graff G. (2008). Blood pressure associated with sleep-disordered breathing in a population sample of children. Hypertension 52, 841–846 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.108.116756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bixler E. O., Vgontzas A. N., Lin H. M., Ten Have T., Leiby B. E., Vela-Bueno A., Kales A. (2000). Association of hypertension and sleep-disordered breathing. Arch. Intern. Med. 160, 2289–2295 10.1001/archinte.160.15.2289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonsignore M. R., Parati G., Insalaco G., Castiglioni P., Marrone O., Romano S., Salvaggio A., Mancia G., Bonsignore G., Di Rienzo M. (2006). Baroreflex control of heart rate during sleep in severe obstructive sleep apnoea: effects of acute CPAP. Eur. Respir. J. 27, 128–135 10.1183/09031936.06.00042904 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgel J., Sanner B. M., Keskin F., Bittlinsky A., Bartels N. K., Buchner N., Huesing A., Rump L. C., Mugge A. (2004). Obstructive sleep apnea and blood pressure. Interaction between the blood pressure-lowering effects of positive airway pressure therapy and antihypertensive drugs. Am. J. Hypertens. 17, 1081–1087 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.06.026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brietzke S. E., Katz E. S., Roberson D. W. (2007). Pulse transit time as a screening test for pediatric sleep-related breathing disorders. Arch. Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 133, 980–984 10.1001/archotol.133.10.980 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks D., Horner R. L., Floras J. S., Kozar L. F., Render-Teixeira C. L., Phillipson E. A. (1999). Baroreflex control of heart rate in a canine model of obstructive sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 159, 1293–1297 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano-Pumarega I., Duran-Cantolla J., Aizpuru F., Miranda-Serrano E., Rubio R., Martinez-Null C., De Miguel J., Barbe F. (2011). Obstructive sleep apnea and systemic hypertension: longitudinal study in the general population. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184, 1299–1304 10.1164/rccm.201101-0130OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlson J. T., Hedner J., Elam M., Ejnell H., Sellgren J., Wallin B. G. (1993). Augmented resting sympathetic activity in awake patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 103, 1763–1768 10.1378/chest.103.6.1763 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan E., Steenland H. W., Liu H., Horner R. L. (2006). Endogenous excitatory drive modulating respiratory muscle activity across sleep-wake states. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 174, 1264–1273 10.1164/rccm.200509-1420OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheezum M. K., Lettieri C. J. (2010). Obstructive sleep apnea presenting as pseudopheochromocytoma. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 6, 190–191 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng J. H., Hua C. C., Chen N. H., Liu Y. C., Yu C. C. (2011). Autonomic activity difference during continuous positive airway pressure titration in patients with obstructive sleep apnea/hypopnea syndrome with or without hypertension. Chang Gung Med. J. 34, 410–417 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choi J. H., Yi J. S., Lee S. H., Kim C. S., Kim T. H., Lee H. M., Lee B. J., Chung Y. S. (2011). Effect of upper airway surgery on heart rate variability in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. J. Sleep Res. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00978.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comondore V. R., Cheema R., Fox J., Butt A., John Mancini G. B., Fleetham J. A., Ryan C. F., Chan S., Ayas N. T. (2009). The impact of CPAP on cardiovascular biomarkers in minimally symptomatic patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a pilot feasibility randomized crossover trial. Lung 187, 17–22 10.1007/s00408-008-9115-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantin E., Mcgregor C. D., Cote V., Brouillette R. T. (2008). Pulse rate and pulse rate variability decrease after adenotonsillectomy for obstructive sleep apnea. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 43, 498–504 10.1002/ppul.20811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper V. L., Elliott M. W., Pearson S. B., Taylor C. M., Mohammed M. M., Hainsworth R. (2007). Daytime variability of baroreflex function in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea: implications for hypertension. Exp. Physiol. 92, 391–398 10.1113/expphysiol.2006.035584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dematteis M., Julien C., Guillermet C., Sturm N., Lantuejoul S., Mallaret M., Levy P., Gozal E. (2008). Intermittent hypoxia induces early functional cardiovascular remodeling in mice. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 177, 227–235 10.1164/rccm.200702-238OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng Z. D., Poon C. S., Arzeno N. M., Katz E. S. (2006). Heart rate variability in pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Conf. Proc. IEEE Eng. Med. Biol. Soc. 1, 3565–3568 10.1109/IEMBS.2006.260139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dernaika T. A., Kinasewitz G. T., Tawk M. M. (2009). Effects of nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure therapy in patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. J. Clin. Sleep. Med. 5, 103–107 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhillon S., Chung S. A., Fargher T., Huterer N., Shapiro C. M. (2005). Sleep apnea, hypertension, and the effects of continuous positive airway pressure. Am. J. Hypertens. 18, 594–600 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.11.031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dodig I. P., Pecotic R., Valic M., Dogas Z. (2011). Acute intermittent hypoxia induces phrenic long-term facilitation which is modulated by 5-HT(1A) receptor in the caudal raphe region of the rat. J. Sleep Res. [Epub ahead of print]. 10.1111/j.1365-2869.2011.00948.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drager L. F., Bortolotto L. A., Figueiredo A. C., Krieger E. M., Lorenzi G. F. (2007). Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on early signs of atherosclerosis in obstructive sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 176, 706–712 10.1164/rccm.200703-500OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duran-Cantolla J., Aizpuru F., Montserrat J. M., Ballester E., Teran-Santos J., Aguirregomoscorta J. I., Gonzalez M., Lloberes P., Masa J. F., De La Pena M., Carrizo S., Mayos M., Barbe F. (2010). Continuous positive airway pressure as treatment for systemic hypertension in people with obstructive sleep apnoea: randomised controlled trial. BMJ 341, c5991. 10.1136/bmj.c5991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eckert D. J., Malhotra A., Jordan A. S. (2009). Mechanisms of apnea. Prog. Cardiovasc. Dis. 51, 313–323 10.1016/j.pcad.2008.02.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elenkov I. J., Wilder R. L., Chrousos G. P., Vizi E. S. (2000). The sympathetic nerve – an integrative interface between two supersystems: the brain and the immune system. Pharmacol. Rev. 52, 595–638 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmasry A., Lindberg E., Hedner J., Janson C., Boman G. (2002). Obstructive sleep apnoea and urine catecholamines in hypertensive males: a population-based study. Eur. Respir. J. 19, 511–517 10.1183/09031936.02.00106402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enriori P. J., Sinnayah P., Simonds S. E., Garcia Rudaz C., Cowley M. A. (2011). Leptin action in the dorsomedial hypothalamus increases sympathetic tone to brown adipose tissue in spite of systemic leptin resistance. J. Neurosci. 31, 12189–12197 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2336-11.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Everson C. A., Crowley W. R. (2004). Reductions in circulating anabolic hormones induced by sustained sleep deprivation in rats. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 286, E1060–E1070 10.1152/ajpendo.00553.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Faccenda J. F., Mackay T. W., Boon N. A., Douglas N. J. (2001). Randomized placebo-controlled trial of continuous positive airway pressure on blood pressure in the sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 163, 344–348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fenik V. B., Davies R. O., Kubin L. (2005). REM sleep-like atonia of hypoglossal (XII) motoneurons is caused by loss of noradrenergic and serotonergic inputs. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 172, 1322–1330 10.1164/rccm.200412-1750OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher E. C., Lesske J., Behm R., Miller C. C., Stauss H., Unger T. (1992). Carotid chemoreceptors, systemic blood pressure, and chronic episodic hypoxia mimicking sleep apnea. J. Appl. Physiol. 72, 1978–1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher E. C., Miller J., Schaaf J. W., Fletcher J. G. (1987). Urinary catecholamines before and after tracheostomy in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension. Sleep 10, 35–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fletcher E. C., Orolinova N., Bader M. (2002). Blood pressure response to chronic episodic hypoxia: the renin-angiotensin system. J. Appl. Physiol. 92, 627–633 10.1063/1.1483109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flierl M. A., Rittirsch D., Huber-Lang M., Sarma J. V., Ward P. A. (2008). Catecholamines-crafty weapons in the inflammatory arsenal of immune/inflammatory cells or opening Pandora’s box? Mol. Med. 14, 195–204 10.2119/2007-00105.Flierl [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo J. Y., Bradley A. P., Wilson S. J., Williams G. R., Dakin C., Cooper D. M. (2006). Screening of obstructive and central apnoea/hypopnoea in children using variability: a preliminary study. Acta Paediatr. 95, 561–564 10.1080/08035250500477552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foo J. Y., Lim C. S. (2006). Pulse transit time as an indirect marker for variations in cardiovascular related reactivity. Technol. Health Care 14, 97–108 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foster G. E., Brugniaux J. V., Pialoux V., Duggan C. T., Hanly P. J., Ahmed S. B., Poulin M. J. (2009). Cardiovascular and cerebrovascular responses to acute hypoxia following exposure to intermittent hypoxia in healthy humans. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 587, 3287–3299 10.1113/jphysiol.2009.171553 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman O., Logan A. G. (2009). Sympathoadrenal mechanisms in the pathogenesis of sleep apnea-related hypertension. Curr. Hypertens. Rep. 11, 212–216 10.1007/s11906-009-0037-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gapelyuk A., Riedl M., Suhrbier A., Kraemer J. F., Bretthauer G., Malberg H., Kurths J., Penzel T., Wessel N. (2011). Cardiovascular regulation in different sleep stages in the obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Biomed. Tech. (Berl.) 56, 207–213 10.1515/BMT.2011.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin G. S., Lynch M., Tamisier R., Weiss J. W. (2010). Chronic intermittent hypoxia in humans during 28 nights results in blood pressure elevation and increased muscle sympathetic nerve activity. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 299, H925–H931 10.1152/ajpheart.00253.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmartin G. S., Tamisier R., Curley M., Weiss J. W. (2008). Ventilatory, hemodynamic, sympathetic nervous system, and vascular reactivity changes after recurrent nocturnal sustained hypoxia in humans. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 295, H778–H785 10.1152/ajpheart.00653.2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golbidi S., Badran M., Ayas N., Laher I. (2011). Cardiovascular consequences of sleep apnea. Lung. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Martin M. C., Vega-Agapito M. V., Conde S. V., Castaneda J., Bustamante R., Olea E., Perez-Vizcaino F., Gonzalez C., Obeso A. (2011). Carotid body function and ventilatory responses in intermittent hypoxia. Evidence for anomalous brainstem integration of arterial chemoreceptor input. J. Cell. Physiol. 226, 1961–1969 10.1002/jcp.22528 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Martin M. C., Vega-Agapito V., Prieto-Lloret J., Agapito M. T., Castaneda J., Gonzalez C. (2009). Effects of intermittent hypoxia on blood gases plasma catecholamine and blood pressure. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 648, 319–328 10.1007/978-90-481-2259-2_36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal D., Kheirandish-Gozal L. (2008). Cardiovascular morbidity in obstructive sleep apnea: oxidative stress, inflammation, and much more. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 177, 369–375 10.1164/rccm.200608-1190PP [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gozal D., Kheirandish-Gozal L., Serpero L. D., Sans Capdevila O., Dayyat E. (2007). Obstructive sleep apnea and endothelial function in school-aged nonobese children: effect of adenotonsillectomy. Circulation 116, 2307–2314 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.696823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenberg H. E., Sica A., Batson D., Scharf S. M. (1999). Chronic intermittent hypoxia increases sympathetic responsiveness to hypoxia and hypercapnia. J. Appl. Physiol. 86, 298–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu H., Lin M., Liu J., Gozal D., Scrogin K. E., Wurster R., Chapleau M. W., Ma X., Cheng Z. J. (2007). Selective impairment of central mediation of baroreflex in anesthetized young adult Fischer 344 rats after chronic intermittent hypoxia. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 293, H2809–H2818 10.1152/ajpheart.00358.2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilleminault C., Lee J. H., Chan A. (2005). Pediatric obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 159, 775–785 10.1001/archpedi.159.8.775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guyenet P. G. (2006). The sympathetic control of blood pressure. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 7, 335–346 10.1038/nrn1902 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heitmann J., Ehlenz K., Penzel T., Becker H. F., Grote L., Voigt K. H., Peter J. H., Vogelmeier C. (2004). Sympathetic activity is reduced by nCPAP in hypertensive obstructive sleep apnoea patients. Eur. Respir. J. 23, 255–262 10.1183/09031936.04.00015604 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horner R. L., Brooks D., Kozar L. F., Tse S., Phillipson E. A. (1995). Immediate effects of arousal from sleep on cardiac autonomic outflow in the absence of breathing in dogs. J. Appl. Physiol. 79, 151–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hornyak M., Cejnar M., Elam M., Matousek M., Wallin B. G. (1991). Sympathetic muscle nerve activity during sleep in man. Brain 114(Pt 3), 1281–1295 10.1093/brain/114.3.1281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui A. S., Striet J. B., Gudelsky G., Soukhova G. K., Gozal E., Beitner-Johnson D., Guo S. Z., Sachleben L. R., Jr., Haycock J. W., Gozal D., Czyzyk-Krzeska M. F. (2003). Regulation of catecholamines by sustained and intermittent hypoxia in neuroendocrine cells and sympathetic neurons. Hypertension 42, 1130–1136 10.1161/01.HYP.0000101691.12358.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hui D. S., To K. W., Ko F. W., Fok J. P., Chan M. C., Ngai J. C., Tung A. H., Ho C. W., Tong M. W., Szeto C. C., Yu C. M. (2006). Nasal CPAP reduces systemic blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnoea and mild sleepiness. Thorax 61, 1083–1090 10.1136/thx.2006.064063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imadojemu V. A., Mawji Z., Kunselman A., Gray K. S., Hogeman C. S., Leuenberger U. A. (2007). Sympathetic chemoreflex responses in obstructive sleep apnea and effects of continuous positive airway pressure therapy. Chest 131, 1406–1413 10.1378/chest.06-2580 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip M. S., Tse H. F., Lam B., Tsang K. W., Lam W. K. (2004). Endothelial function in obstructive sleep apnea and response to treatment. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 169, 348–353 10.1164/rccm.200306-767OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iturriaga R., Moya E. A., Del Rio R. (2009). Carotid body potentiation induced by intermittent hypoxia: implications for cardiorespiratory changes induced by sleep apnoea. Clin. Exp. Pharmacol. Physiol. 36, 1197–1204 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2009.05213.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaditis A. G., Alexopoulos E. I., Dalapascha M., Papageorgiou K., Kostadima E., Kaditis D. G., Gourgoulianis K., Zakynthinos E. (2010). Cardiac systolic function in Greek children with obstructive sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep Med. 11, 406–412 10.1016/j.sleep.2009.05.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaditis A. G., Alexopoulos E. I., Damani E., Hatzi F., Chaidas K., Kostopoulou T., Tzigeroglou A., Gourgoulianis K. (2009). Urine levels of catecholamines in Greek children with obstructive sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatr. Pulmonol. 44, 38–45 10.1002/ppul.21126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kara T., Narkiewicz K., Somers V. K. (2003). Chemoreflexes – physiology and clinical implications. Acta Physiol. Scand. 177, 377–384 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01083.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai T., Bradley T. D. (2011). Obstructive sleep apnea and heart failure: pathophysiologic and therapeutic implications. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57, 119–127 10.1016/S0735-1097(11)60167-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katz E. S., Lutz J., Black C., Marcus C. L. (2003). Pulse transit time as a measure of arousal and respiratory effort in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Pediatr. Res. 53, 580–588 10.1203/01.PDR.0000057206.14698.47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly A., Dougherty S., Cucchiara A., Marcus C. L., Brooks L. J. (2010). Catecholamines, adiponectin, and insulin resistance as measured by HOMA in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep 33, 1185–1191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesek M., Franklin K. A., Sahlin C., Lindberg E. (2009). Heart rate variability during sleep and sleep apnoea in a population based study of 387 women. Clin. Physiol. Funct. Imaging 29, 309–315 10.1111/j.1475-097X.2009.00873.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J., Hakim F., Kheirandish-Gozal L., Gozal D. (2011). Inflammatory pathways in children with insufficient or disordered sleep. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 178, 465–474 10.1016/j.resp.2011.04.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline D. D. (2010). Chronic intermittent hypoxia affects integration of sensory input by neurons in the nucleus tractus solitarii. Respir. Physiol. Neurobiol. 174, 29–36 10.1016/j.resp.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler M., Pepperell J. C., Casadei B., Craig S., Crosthwaite N., Stradling J. R., Davies R. J. (2008). CPAP and measures of cardiovascular risk in males with OSAS. Eur. Respir. J. 32, 1488–1496 10.1183/09031936.00012108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler M., Stoewhas A. C., Ayers L., Senn O., Bloch K. E., Russi E. W., Stradling J. R. (2011). The effects of CPAP therapy withdrawal in patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomised controlled trial. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 184, 1192–1199 10.1164/rccm.201106-0964OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohler M., Stradling J. R. (2010). Mechanisms of vascular damage in obstructive sleep apnea. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 7, 677–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohyama J., Ohinata J. S., Hasegawa T. (2003). Blood pressure in sleep disordered breathing. Arch. Dis. Child. 88, 139–142 10.1136/adc.88.2.139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubin L., Davies R. O., Pack A. I. (1998). Control of upper airway motoneurons during REM Sleep. News Physiol. Sci. 13, 91–97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Rovere M. T., Bigger J. T., Jr., Marcus F. I., Mortara A., Schwartz P. J. (1998). Baroreflex sensitivity and heart-rate variability in prediction of total cardiac mortality after myocardial infarction. ATRAMI (autonomic tone and reflexes after myocardial infarction) investigators. Lancet 351, 478–484 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)11144-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai C. J., Yang C. C., Hsu Y. Y., Lin Y. N., Kuo T. B. (2006). Enhanced sympathetic outflow and decreased baroreflex sensitivity are associated with intermittent hypoxia-induced systemic hypertension in conscious rats. J. Appl. Physiol. 100, 1974–1982 10.1152/japplphysiol.01051.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert E., Straznicky N. E., Dawood T., Ika-Sari C., Grima M., Esler M. D., Schlaich M. P., Lambert G. W. (2011). Change in sympathetic nerve firing pattern associated with dietary weight loss in the metabolic syndrome. Front. Physiol. 2:52. 10.3389/fphys.2011.00052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leiter J. C., Knuth S. L., Bartlett D., Jr. (1985). The effect of sleep deprivation on activity of the genioglossus muscle. Am. Rev. Respir. Dis. 132, 1242–1245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lesske J., Fletcher E. C., Bao G., Unger T. (1997). Hypertension caused by chronic intermittent hypoxia – influence of chemoreceptors and sympathetic nervous system. J. Hypertens. 15, 1593–1603 10.1097/00004872-199715120-00060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leuenberger U., Jacob E., Sweer L., Waravdekar N., Zwillich C., Sinoway L. (1995). Surges of muscle sympathetic nerve activity during obstructive apnea are linked to hypoxemia. J. Appl. Physiol. 79, 581–588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung L. C., Ng D. K., Lau M. W., Chan C. H., Kwok K. L., Chow P. Y., Cheung J. M. (2006). Twenty-four-hour ambulatory BP in snoring children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Chest 130, 1009–1017 10.1378/chest.130.4.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Ai J., Li L., Huang C., Chapleau M. W., Liu R., Gozal D., Wead W. B., Wurster R. D., Cheng Z. J. (2008). Structural remodeling of nucleus ambiguous projections to cardiac ganglia following chronic intermittent hypoxia in C57BL/6J mice. J. Comp. Neurol. 509, 103–117 10.1002/cne.21732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin M., Liu R., Gozal D., Wead W. B., Chapleau M. W., Wurster R., Cheng Z. J. (2007). Chronic intermittent hypoxia impairs baroreflex control of heart rate but enhances heart rate responses to vagal efferent stimulation in anesthetized mice. Am. J. Physiol. Heart Circ. Physiol. 293, H997–H1006 10.1152/ajpheart.01124.2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loredo J. S., Ziegler M. G., Ancoli-Israel S., Clausen J. L., Dimsdale J. E. (1999). Relationship of arousals from sleep to sympathetic nervous system activity and BP in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 116, 655–659 10.1378/chest.116.3.655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lumeng J. C., Chervin R. D. (2008). Epidemiology of pediatric obstructive sleep apnea. Proc. Am. Thorac. Soc. 5, 242–252 10.1513/pats.200708-135MG [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahamed S., Mitchell G. S. (2008). Respiratory long-term facilitation: too much or too little of a good thing? Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 605, 224–227 10.1007/978-0-387-73693-8_39 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcus C. L., Greene M. G., Carroll J. L. (1998). Blood pressure in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 157, 1098–1103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrone O., Salvaggio A., Bue A. L., Bonanno A., Riccobono L., Insalaco G., Bonsignore M. R. (2011). Blood pressure changes after automatic and fixed CPAP in obstructive sleep apnea: relationship with nocturnal sympathetic activity. Clin. Exp. Hypertens. 33, 373–380 10.3109/10641963.2010.531853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mastorci F., Vicentini M., Viltart O., Manghi M., Graiani G., Quaini F., Meerlo P., Nalivaiko E., Maccari S., Sgoifo A. (2009). Long-term effects of prenatal stress: changes in adult cardiovascular regulation and sensitivity to stress. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 33, 191–203 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2008.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell K., Somers V. K., Kimball T., Daniels S., Vandyke R., Fenchel M., Cohen A., Willging P., Shamsuzzaman A., Amin R. (2009). Baroreflex gain in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 180, 42–48 10.1164/rccm.200808-1324OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills P. J., Kennedy B. P., Loredo J. S., Dimsdale J. E., Ziegler M. G. (2006). Effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure and oxygen supplementation on norepinephrine kinetics and cardiovascular responses in obstructive sleep apnea. J. Appl. Physiol. 100, 343–348 10.1152/japplphysiol.00494.2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Minemura H., Akashiba T., Yamamoto H., Akahoshi T., Kosaka N., Horie T. (1998). Acute effects of nasal continuous positive airway pressure on 24-hour blood pressure and catecholamines in patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Intern. Med. 37, 1009–1013 10.2169/internalmedicine.37.1009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molkov Y. I., Zoccal D. B., Moraes D. J., Paton J. F., Machado B. H., Rybak I. A. (2011). Intermittent hypoxia-induced sensitization of central chemoreceptors contributes to sympathetic nerve activity during late expiration in rats. J. Neurophysiol. 105, 3080–3091 10.1152/jn.00070.2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan K. D., Leuenberger U. A., Ray C. A. (2006). Effect of repetitive hypoxic apnoeas on baroreflex function in humans. J. Physiol. (Lond.) 574, 605–613 10.1113/jphysiol.2006.108977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Montesano M., Miano S., Paolino M. C., Massolo A. C., Ianniello F., Forlani M., Villa M. P. (2010). Autonomic cardiovascular tests in children with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep 33, 1349–1355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan B. J., Crabtree D. C., Puleo D. S., Badr M. S., Toiber F., Skatrud J. B. (1996). Neurocirculatory consequences of abrupt change in sleep state in humans. J. Appl. Physiol. 80, 1627–1636 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muzumdar H. V., Sin S., Nikova M., Gates G., Kim D., Arens R. (2011). Changes in heart rate variability after adenotonsillectomy in children with obstructive sleep apnea. Chest 139, 1050–1059 10.1378/chest.10-1555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakra N., Bhargava S., Dzuira J., Caprio S., Bazzy-Asaad A. (2008). Sleep-disordered breathing in children with metabolic syndrome: the role of leptin and sympathetic nervous system activity and the effect of continuous positive airway pressure. Pediatrics 122, e634–e42 10.1542/peds.2008-0154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K., Kato M., Phillips B. G., Pesek C. A., Davison D. E., Somers V. K. (1999a). Nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure decreases daytime sympathetic traffic in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 100, 2332–2335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K., Van De Borne P. J., Pesek C. A., Dyken M. E., Montano N., Somers V. K. (1999b). Selective potentiation of peripheral chemoreflex sensitivity in obstructive sleep apnea. Circulation 99, 1183–1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narkiewicz K., Somers V. K. (2003). Sympathetic nerve activity in obstructive sleep apnoea. Acta Physiol. Scand. 177, 385–390 10.1046/j.1365-201X.2003.01091.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newacheck P. W., Taylor W. R. (1992). Childhood chronic illness: prevalence, severity, and impact. Am. J. Public Health 82, 364–371 10.2105/AJPH.82.3.364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norman D., Loredo J. S., Nelesen R. A., Ancoli-Israel S., Mills P. J., Ziegler M. G., Dimsdale J. E. (2006). Effects of continuous positive airway pressure versus supplemental oxygen on 24-hour ambulatory blood pressure. Hypertension 47, 840–845 10.1161/01.HYP.0000217128.41284.78 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien L. M., Gozal D. (2005). Autonomic dysfunction in children with sleep-disordered breathing. Sleep 28, 747–752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]