Abstract

Statins are best-selling medications in the management of high cholesterol and associated cardiovascular complications. They inhibit 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA)-reductase in order to prevent disproportionate cholesterol synthesis. Statins slow the progression of atherosclerosis, prevent the secondary cardiovascular events and improve the cardiovascular outcomes in patients with elevated cholesterol levels. The underlying mechanisms pertaining to the cardioprotective role of statins are linked with numerous pleiotropic actions including inhibition of inflammatory events and improvement of endothelial function, besides an effective cholesterol-lowering ability. Intriguingly, recent studies suggest possible interplay between statins and nuclear transcription factors like PPARs, which should also be taken into consideration while analysing the potential of statins in the management of cardiovascular complications. It could be suggested that statins have two major roles: (i) a well-established cholesterol-lowering effect through inhibition of HMG-CoA-reductase; (ii) a newly explored PPAR-activating property, which could mediate most of cardiovascular protective pleiotropic effects of statins including anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-fibrotic properties. The present review addressed the underlying principles pertaining to the modulatory role of statins on PPARs.

Keywords: statins, PPARs, cardiovascular complications

Introduction

Accumulating evidences prove dramatic reduction in the risk of major cardiovascular events by statins, 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A (HMG-CoA)-reductase inhibitors, which primarily lower the levels of low-density lipoprotein (LDL) and total cholesterol. Lovastatin, pravastatin and fluvastatin are first-generation statins, while atorvastatin and simvastatin are second-generation statins and rosuvastatin is a third-generation statin developed for the management of dyslipidaemia (Kapur and Musunuru, 2008). It has been revealed that statins can reduce blood pressure in hypertensive patients (Golomb et al., 2008) with an incompletely known mechanism. Pravastatin significantly reduced cardiac angiotensin-II levels and subsequently normalized peripheral cardiac sympathetic hyperactivity in spontaneously hypertensive rats (Herring et al., 2011), explaining the possible mechanism involved in statin-mediated blood pressure control. In addition, it has been suggested that atorvastatin may regress the remodelling of pulmonary artery in pulmonary hypertensive rats (Xie et al., 2010). Early treatment with atorvastatin or simvastatin reduced mortality in patients of non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy with severe heart failure, independently of their lipid-lowering effects (Li et al., 2010). Statins possess, besides cholesterol-lowering action, numerous pleiotropic properties including nitric oxide-mediated improvement in endothelial function, antioxidant effects, anti-inflammatory properties and prevention of atherosclerotic plaque formation (Treasure et al., 1995; Masumoto et al., 2001; Kapur and Musunuru, 2008), all of which collectively could be involved in statin-mediated improvement of cardiovascular outcomes. PPARs are key transcriptional regulators of carbohydrate and lipid metabolism and energy production. PPARs have been suggested to play an important role in the regulation of cardiovascular and renal function (Balakumar et al., 2007a,b; 2009; Arora et al., 2010; Balakumar and Jagadeesh, 2010; Kaur et al., 2010). Fenofibrate, an activator of PPARα, is commonly employed to treat hypertriglyceridaemia and mixed dyslipidaemia (Zambon and Cusi, 2007). It has been suggested that fenofibrate possesses direct cardioprotective action through its anti-inflammatory, antioxidant and anti-fibrotic properties on the heart (Ogata et al., 2002; 2004; Diep et al., 2004; Chen et al., 2007; Balakumar et al., 2011). On the other hand, pioglitazone, an activator of PPARγ, is usually employed to treat insulin resistance-associated incidence of diabetes mellitus, and pioglitazone may have an ability to afford protection from cardiovascular events in diabetic patients (Kaul et al., 2010). Worthy of note that recent studies demonstrated a novel pharmacological link between statins and PPARs signalling (Paumelle et al., 2006; Yano et al., 2007; Huang et al., 2009; Shen et al., 2010). In this review, we enlightened that the cardioprotective potentials of statins could also be mediated through pleiotropic activation of PPARs.

A potential interplay between statins and PPARs: a profound look

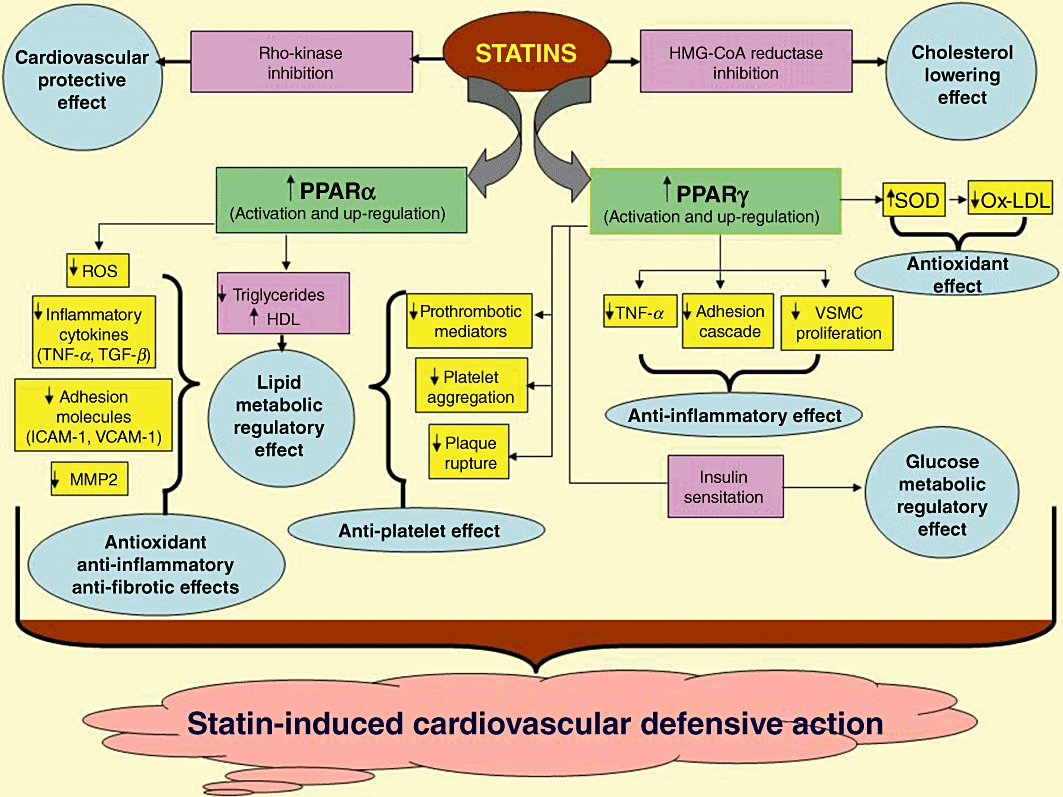

A growing body of evidence suggests a potential interplay between statins and PPARs. In fact, statins have a protective role on cardiovascular abnormalities besides cholesterol-lowering effect, and their cardioprotective potentials could be partly related to a mechanism eventually linking PPARs (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Depicted here are multi-pronged mechanisms involved in PPAR-dependent cardiovascular defensive role of statins. SOD, superoxide dismutase HDL, high-density lipoprotein; ROS, reactive oxygen species; ICAM-1, inter-cellular adhesion molecule-1; VCAM-1, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1; VSMC, vascular smooth muscle cells.

PPAR-dependent effects of statins on lipoprotein metabolism

It is evidenced that statins can induce lipid metabolism by also activating PPARα and enhancing its expression. Roglans et al. (2002) investigated the effect of atorvastatin on hepatic lipid metabolism in the fructose-fed hypertriglyceridaemic rat. Fructose feeding (10% fructose in drinking water for 2 weeks) reduced PPARα expression and subsequently induced hepatic lipogenesis. However, interestingly, treatment with atorvastatin increased PPARα expression and reduced liver triglyceride levels (Roglans et al., 2002). It is worth mentioning that senescent rats are resistant to fibrate-induced hypolipidaemic action as they are associated with decreased expression of PPARα (Sanguino et al., 2005). Intriguingly, administration of atorvastatin in 18 month old senescent rats increased hepatic PPARα mRNA (2.2-fold) and PPARα protein (1.6-fold) levels and enhanced PPARα-binding activity as well (Sanguino et al., 2005). Thus, the induction of significant changes in PPARα expression could be responsible for atorvastatin-induced improvement of lipid metabolic phenotype in senescent rats. A study by Huang et al. (2009) showed that the combination of atorvastatin and fenofibrate in fructose-fed hypertriglyceridaemic rats afforded a greater degree of reduction in triglyceride levels as a result of marked up-regulation of hepatic PPARα expression (Huang et al., 2009). This result has been substantiated by a recent report that atorvastatin reduced triglyceride levels via activating PPARα in hypertriglyceridaemic rats (Huang et al., 2010). These studies certainly emphasized a statement of statin-mediated up-regulation and activation of PPARα, which could be a target mediator of effects produced by both statins and fibrates (fenofibrate, gemfibrozil, etc.) on hepatic lipoprotein metabolism. However, further studies are needed to explore the signalling mechanism involved in statin-mediated up-regulation and activation of PPARα.

PPAR-dependent anti-inflammatory effects of statins

It has been evidenced from numerous studies that PPARs could mediate the pleiotropic anti-inflammatory effects of statins. Interestingly, Yano et al. (2007) demonstrated that the anti-inflammatory and anti-atherogenic properties of statins (fluvastatin, simvastatin, atorvastatin, pitavastatin, cerivastatin) were associated with pleiotropic activations of PPARα and PPARγ. The authors of this study showed that statins induce COX-2-dependent increase in 15-deoxy-delta (12,14)-prostaglandin J2 (15d-PGJ2) through RhoA and p38 MAPK signalling and thereby activating PPARγ (Yano et al., 2007). Likewise, Paumelle et al. (2006) demonstrated that the acute anti-inflammatory property of statins involves PPARα via inhibition of the PKC signalling pathway (Paumelle et al., 2006), as the PKC signalling is known to regulate a molecular switch between transactivation and transrepression activity of PPARα (Blanquart et al., 2004). It is worthwhile to note that statins such as simvastatin, fluvastatin and cerivastatin significantly reduced IL-1β and IL-6 mRNA expression and their protein levels, markedly decreased mRNA levels of p22phox and p47phox (subunits of NADPH oxidase) and also inhibited COX-2 mRNA expression and their protein levels in primary endothelial cells, which were considerably accompanied with induction of PPARα and PPARγ mRNA expression and their protein levels (Inoue et al., 2000). These distinctive anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of statins, in addition to their cholesterol-lowering effect, may be of potential therapeutic value in preventing the vascular complications induced by hyperlipidaemia. Furthermore, Zelvyte et al. (2002) showed that pravastatin increased PPARγ levels and abolished NF-κB activity in vitro. The addition of pravastatin to monocytes prior to or after treatment with native or oxidized LDL (nLDL or oxLDL) significantly inhibited the generation of fibrotic and inflammatory mediators such as MMPs, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) and TNF-α, highlighting pravastatin-mediated involvement of PPARγ in the inhibition of inflammatory events (Zelvyte et al., 2002). Similarly, Grip et al. (2002) demonstrated that atorvastatin activated PPARγ and followed by markedly inhibiting the production of TNF-α, MCP-1 and gelatinase in a concentration-dependent manner in primary human monocytes (Grip et al., 2002). Taken together, these findings strongly suggest that statins would have an ability to diminish inflammatory cascades via activation of PPARs, which could, perhaps, explain the involvement of additional molecular mechanism pertaining to the protective effects of statins on cardiovascular system. This contention has been explained in the following section with substantial evidences.

PPAR-dependent cardioprotective effects of statins

Needless to mention that statins have a therapeutic potential to prevent cardiac abnormalities, it remains, however, uncertain to describe the precise mechanism/s associated with the defensive potential of statins against cardiac complications. Nevertheless, one reasonable explanation resides in the fact that the interplay between statins and PPARs, in addition to their cholesterol-lowering effect, may be a key mechanism of cardioprotective effects exerted by statins. To support this notion, Sheng et al. (2005) investigated the effect of atorvastatin on angiotensin-II-induced hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes in relation to changes in PPARα and PPARγ mRNA expression. Treatment with atorvastatin up-regulated the expression of PPARα and PPARγ and consequently inhibited the hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes in vitro by decreasing the mRNA expression of markers of cardiac hypertrophy such as atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP), brain natriuretic peptide (BNP), MMP9, MMP2 and IL-1β (Sheng et al., 2005). Subsequently, an in vivo anti-hypertrophic potential of atorvastatin was reported. Administration of atorvastatin in pressure-overloaded rats markedly prevented the development of cardiac hypertrophy (assessed in terms of increase in the ratio of heart weight to body weight, left ventricular wall thickness and myocyte diameter) by attenuating the down-regulation of PPARγ mRNA and inhibiting the mRNA expression of BNP, IL-1β and MMP9 (Ye et al., 2006). Moreover, it has been shown that apolipoprotein E-deficient (ApoE−/−) mice fed with ‘Western-style diet’ developed cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis by an increase in age. However, simvastatin treatment inhibited the development of cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in ApoE−/− mice by significantly increasing both PPARα and PPARγ expression (Qin et al., 2010). As a whole, statins have a potential in the prevention of cardiac abnormalities including cardiac hypertrophy through a pleiotropic activation of PPARα and PPARγ in the heart and subsequent inhibition of myocardial inflammation and cardiac fibrosis. In a recent study by Shen et al. (2010), it has been more evidenced that simvastatin pretreatment, in a rat model of cardiopulmonary bypass, significantly decreased myocardial expression of inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α, IL-6 and MCP-1. Such myocardial anti-inflammatory effect of simvastatin was suggested to be partly related to an activation of PPARγ and inhibition of NF-κB signalling (Shen et al., 2010). This study further confirms the fact that the preventive effect of statins on myocardial inflammation could be mediated by PPAR-linked mechanism.

Statins have also been identified to afford cardioprotection against ischaemia–reperfusion-induced myocardial injury. Ravingerováet al. (2009) suggested that statins have a capability to induce myocardial tolerance in response to ischaemic insult. In this study, the Langendorff-perfused heart isolated from the simvastatin-pretreated normocholesterolaemic rat was subjected to a 30 min global ischaemia and 120 min reperfusion. The baseline PPARα mRNA and protein levels were noted to be increased in the simvastatin-pretreated rat heart, which exhibited smaller infarct size, improved post-ischaemic contractile recovery and lower severity of arrhythmias during ischaemia and early reperfusion, as compared with the ischaemia-reperfused untreated control rat heart. The authors of this study suggested that simvastatin-induced up-regulation of PPARα may have played a pivotal role in preventing ischaemia–reperfusion-induced experimental myocardial injury (Ravingerováet al., 2009). Taken in concert, these studies undoubtedly highlight the existence of interplay between statins and PPARs in improving myocardial outcomes and preventing cardiac structural and functional abnormalities.

PPAR-dependent vascular effects of statins

Studies have revealed the potential of statins in the management of persistently elevated blood pressure through a mechanism that implicates PPARs activation. Treatment with rosuvastatin in the obese dyslipidaemic mouse fully corrected blood pressure and its variability in conjunction with the up-regulation of PPARγ in the aortic arch. Likewise, rosuvastatin increased the expression of PPARγ in isolated endothelial cells (Desjardins et al., 2008). Interestingly, rosuvastatin normalized blood pressure homeostasis in the obese dyslipidaemic mouse independently of changes in body weight and plasma cholesterol (Desjardins et al., 2008). In addition, statins may have pleiotropic anti-platelet action mediated by PPARs. In a small-scale human study, fluvastatin was shown to activate PPARα and PPARγ in platelets and consequently reduce platelet aggregation in response to arachidonic acid ex vivo (Ali et al., 2009). Therefore, up-regulation and activation of PPARs may perhaps be a distinctive mechanism involved in the vascular defensive effects of statins. Additional studies, however, are needed to illuminate the molecular mechanism involved in this contention.

PPAR-dependent renoprotective effects of statins

Statins possess renoprotective effects, which are fractionally mediated by PPARs. Pravastatin has an ability to prevent carboplatin-induced renal dysfunction via a PPAR-dependent mechanism. It has been shown that pravastatin pretreatment in carboplatin-administered mice considerably prevented the induction of renal dysfunction and apoptosis, and improved renal morphology and survival by inducing the expression of PPARα (Chen et al., 2010). In addition, atorvastatin afforded renoprotective effect in rats that underwent unilateral ureteral obstruction by alleviating renal interstitial fibrosis via an activation of PPARγ (Liu et al., 2007). The PPAR-dependent renoprotective effect of statins was further evidenced by the fact that PPARα mediates the anti-inflammatory effect of simvastatin in an experimental model of zymosan-induced renal failure (Rinaldi et al., 2011). These studies pointed out the possibilities of PPAR-dependent renoprotective effects of statins.

Molecular mechanisms involved in statin-mediated activation of PPARs

The precise molecular mechanism involved in statin-mediated PPARs activation is not completely understood. Yano et al. (2007), however, demonstrated possible mechanism/s pertaining to PPAR activation by statins in macrophages. In detail, statins activated PPARγ by suppressing farnesylpyrophosphate and geranylgeranylpyrophosphate, and subsequently inhibiting small GTP-binding proteins like Rho. Statins induced p38 MAPK-dependent COX-2 expression by inhibiting the RhoA signalling pathway. In addition, statin-induced COX-2 expression was also mediated by ERK1/2 activation through a RhoA signalling pathway. These signalling cascades, as a result, certainly increased 15d-PGJ2 levels, which is one of the natural PPARγ ligand activating PPARγ. Additionally, statins activated PPARα via a COX-2-dependent pathway (Yano et al., 2007). Taken together, statins could activate PPARs through ERK1/2 and p38 MAPK-dependent COX-2 expression.

Therapeutic outcomes with combination of statins and PPAR ligands: current perspectives and future directions

Patients of uncontrolled dyslipidaemia are at increased risk for coronary heart disease, and the incidence of which is even higher with diabetes mellitus. Statins primarily lower LDL and total cholesterol, while fibrates (PPARα ligands) appear to have exclusive property of reducing triglycerides, whereas glitazones (PPARγ ligands) have unique property of inducing insulin sensitization followed by glucose metabolism. Thus, the combination of statins with PPAR ligands was proposed to be a most appropriate therapeutic option in the management of metabolic abnormalities associated with diabetic and non-diabetic dyslipidaemic cardiovascular inflammatory disorders. This contention was partially supported by an experimental study in which the combination of pravastatin and pioglitazone had a prospective anti-fibrotic effect in angiotensin-II-administered mouse cardiac fibroblasts, and this combination markedly inhibited angiotensin-II-induced oxidative stress, MAPK activation and procollagen-1 expression (Chen and Mehta, 2006). The following subsection details the clinical outcomes of combination of statins with PPAR ligands.

A multi-centre, randomized, double-blind, active-controlled 18 week study suggested that simvastatin and fenofibrate combination therapy, in patients with combined hyperlipidaemia, resulted in an additional improvement of all lipoprotein parameters as compared to simvastatin monotherapy (Grundy et al., 2005). Subsequently, it was suggested that atorvastatin and fenofibrate combination therapy would be safe and possesses beneficial additive effects on endothelial function in patients with combined hyperlipidaemia (Koh et al., 2005). Moreover, addition of pioglitazone to statin in non-diabetic patients with metabolic syndrome afforded a marked additional benefit in the lipid profile over statin monotherapy (Murdock et al., 2006). It is worth mentioning that treatment with tesaglitazar, a PPAR α/γ dual agonist, further improved the lipid profile in dyslipidaemic subjects co-administered with atorvastatin (Tonstad et al., 2007). A study by Leonhardt et al. (2008) demonstrated a synergistic preventive action of pioglitazone and simvastatin combination therapy on atherogenicity of small dense LDL particles in non-diabetic patients with high cardiovascular risk. Additionally, Sugamura et al. (2008) provided further evidence of a great benefit upon adding pioglitazone to a successful statin therapy in non-diabetic patients with coronary artery disease. Furthermore, co-administration of pioglitazone with atorvastatin in a population at high cardiovascular risk provided additional benefits on endothelial function, lipid profile and markers of inflammation (Forst et al., 2008). These studies collectively suggest that the combination of statins with PPAR ligands may offer a valuable therapeutic option and may be beneficial in diabetic and non-diabetic subjects with dyslipidaemic cardiovascular inflammatory disorders. Though the combination of statins with PPAR ligands could provide considerable benefits in preventing the progression of cardiovascular disorders, the long-term benefits and the adverse profile on the combination of statins and PPAR ligands upon chronic treatment are uncertain and are needed to be investigated.

Adverse effects of statins: is there a role of PPARs?

The chronic use of statins has been infrequently associated with myositis and rhabdomyolysis (Mukhtar and Reckless, 2005; Antons et al., 2006). It remains question whether these potential adverse effects of statins unswervingly involve the role of PPARs. It must be cautiously noted that fibrates, being PPARα activators, have been reported to have potential risk of inducing rhabdomyolysis (Wu et al., 2009). Thus, it could be possible that statin-mediated induction of myositis and rhabdomyolysis may be associated with PPARα activation. However, there is no direct evidence at present available to support this contention impeccably. Moreover, some newly defined side effects have been also shown. Statins may interfere with cardioprotective and infarct size-limiting potentials of ischaemic pre- and post-conditioning (Kocsis et al., 2008), which could possibly involve an altered expression pattern of PPARγ (Onody et al., 2003). These studies suggest a feasible cross-talk between PPARs and statin-induced adverse events.

Concluding remarks

An increased risk of coronary heart disease has been reported with rosiglitazone, a PPARγ agonist (Nissen and Wolski, 2007), and it may increase the risk of myocardial ischaemic events by 30–40% (Schernthaner and Chilton, 2010). The exact mechanism pertaining to rosiglitazone-induced coronary heart damage, however, is not known and may be unrelated to PPARγ activation. Because another PPARγ agonist, pioglitazone (the only available glitazone in clinical use at present), does not increase the risk of coronary events, and even its treatment may afford protection against detrimental cardiovascular events in diabetic patients (Kaul et al., 2010; Schernthaner and Chilton, 2010). Thus, rosiglitazone-associated risk of coronary heart disease may be unrelated to PPARγ activation or may be due to PPARγ-mediated different gene expression pattern.

Statins have a prominent role of inhibiting HMG-CoA reductase and alongside submaximal role of modulating the expression pattern and activation of PPARs. The interplay between statins and PPARs may put forward perspectives in the treatment of diabetic and non-diabetic subjects with cardiovascular complications and dyslipidaemia. The pleiotropic anti-inflammatory, anti-atherogenic, anti-fibrotic and antioxidant properties of statins could explain their cardiovascular protective potentials, which could be mediated through activation and up-regulation of PPARs. The long-term clinical studies are obligatory to enlighten the effect of chronic treatment of the combination of statins with either fenofibrate like PPARα ligands (non-diabetic condition) or pioglitazone like PPARγ ligands (diabetic condition) in the management of cardiovascular complications in hyperlipidaemic subjects with myocardial inflammation and fibrosis.

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Dr Rajender Singh, Chairman and Shri. Om Parkash, director, Rajendra Institute of Technology and Sciences (RITS), Sirsa-Haryana, India, for their inspiration and constant support to accomplish this study.

Glossary

- 15d-PGJ2

15-deoxy-delta(12,14)-prostaglandin J2

- ANP

atrial natriuretic peptide

- BNP

brain natriuretic peptide

- HMG-CoA

3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-coenzyme A

- LDL

low-density lipoprotein

- MCP-1

monocyte chemotactic protein-1

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- Alexander SPH, Mathie A, Peters JA. Guide to Receptors and Channels (GRAC), 5th edition. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164:S1–S324. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01649_1.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ali FY, Armstrong PC, Dhanji AR, Tucker AT, Paul-Clark MJ, Mitchell JA, et al. Antiplatelet actions of statins and fibrates are mediated by PPARs. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2009;29:706–711. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.183160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antons KA, Williams CD, Baker SK, Phillips PS. Clinical perspectives of statin-induced rhabdomyolysis. Am J Med. 2006;119:400–409. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2006.02.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arora MK, Reddy K, Balakumar P. The low dose combination of fenofibrate and rosiglitazone halts the progression of diabetes-induced experimental nephropathy. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;636:137–144. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakumar P, Jagadeesh G. Multifarious molecular signaling cascades of cardiac hypertrophy: can the muddy waters be cleared? Pharmacol Res. 2010;62:365–383. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakumar P, Rose M, Ganti SS, Krishan P, Singh M. PPAR dual agonists: are they opening Pandora's Box? Pharmacol Res. 2007a;56:91–98. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2007.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakumar P, Rose M, Singh M. PPAR ligands: are they potential agents for cardiovascular disorders? Pharmacology. 2007b;80:1–10. doi: 10.1159/000102594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakumar P, Arora MK, Singh M. Emerging role of PPAR ligands in the management of diabetic nephropathy. Pharmacol Res. 2009;60:170–173. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2009.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balakumar P, Rohilla A, Mahadevan N. Pleiotropic actions of fenofibrate on the heart. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:8–12. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blanquart C, Mansouri R, Paumelle R, Fruchart JC, Staels B, Glineur C. The protein kinase C signaling pathway regulates a molecular switch between transactivation and transrepression activity of the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha. Mol Endocrinol. 2004;18:1906–1918. doi: 10.1210/me.2003-0327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HH, Chen TW, Lin H. Pravastatin attenuates carboplatin-induced nephrotoxicity in rodents via peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha-regulated heme oxygenase-1. Mol Pharmacol. 2010;78:36–45. doi: 10.1124/mol.109.061101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen HJ, Chen JZ, Wang XX, Yu M. PPAR alpha activator fenofibrate regressed left ventricular hypertrophy and increased myocardium PPAR alpha expression in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Zhejiang Da Xue Xue Bao Yi Xue Ban. 2007;36:470–476. doi: 10.3785/j.issn.1008-9292.2007.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Mehta JL. Angiotensin II-mediated oxidative stress and procollagen-1 expression in cardiac fibroblasts: blockade by pravastatin and pioglitazone. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2006;291:H1738–H1745. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00341.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desjardins F, Sekkali B, Verreth W, Pelat M, De Keyzer D, Mertens A, et al. Rosuvastatin increases vascular endothelial PPARgamma expression and corrects blood pressure variability in obese dyslipidaemic mice. Eur Heart J. 2008;29:128–137. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diep QN, Benkirane K, Amiri F, Cohn JS, Endemann D, Schiffrin EL. PPAR alpha activator fenofibrate inhibits myocardial inflammation and fibrosis in angiotensin II-infused rats. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2004;36:295–304. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2003.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forst T, Wilhelm B, Pfützner A, Fuchs W, Lehmann U, Schaper F, et al. Investigation of the vascular and pleiotropic effects of atorvastatin and pioglitazone in a population at high cardiovascular risk. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2008;5:298–303. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2008.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golomb BA, Dimsdale JE, White HL, Ritchie JB, Criqui MH. Reduction in blood pressure with statins: results from the USCD Statin Study, a randomized trial. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168:721–727. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.7.721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grip O, Janciauskiene S, Lindgren S. Atorvastatin activates PPAR-gamma and attenuates the inflammatory response in human monocytes. Inflamm Res. 2002;51:58–62. doi: 10.1007/BF02684000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundy SM, Vega GL, Yuan Z, Battisti WP, Brady WE, Palmisano J. Effectiveness and tolerability of simvastatin plus fenofibrate for combined hyperlipidemia (the SAFARI trial) Am J Cardiol. 2005;95:462–468. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2004.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herring N, Lee CW, Sunderland N, Wright K, Paterson DJ. Pravastatin normalises peripheral cardiac sympathetic hyperactivity in the spontaneously hypertensive rat. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2011;50:99–106. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2010.09.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XS, Zhao SP, Bai L, Hu M, Zhao W, Zhang Q. Atorvastatin and fenofibrate increase apolipoprotein AV and decrease triglycerides by up-regulating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha. Br J Pharmacol. 2009;158:706–712. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2009.00350.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang XS, Zhao SP, Bai L, Zhang Q, Hu M, Zhao W. Statin reduced triglyceride level via activating peroxisome proliferator activated receptor α and upregulating apolipoprotein A5 in hypertriglyceridemic rats. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2010;38:809–813. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoue I, Goto S, Mizotani K, Awata T, Mastunaga T, Kawai S, et al. Lipophilic HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor has an anti-inflammatory effect: reduction of MRNA levels for interleukin-1beta, interleukin-6, cyclooxygenase-2, and p22phox by regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPARalpha) in primary endothelial cells. Life Sci. 2000;67:863–876. doi: 10.1016/s0024-3205(00)00680-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapur NK, Musunuru K. Clinical efficacy and safety of statins in managing cardiovascular risk. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2008;4:341–353. doi: 10.2147/vhrm.s1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaul S, Bolger AF, Herrington D, Giugliano RP, Eckel RH. Thiazolidinedione drugs and cardiovascular risks: a science advisory from the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology Foundation. Circulation. 2010;121:1868–1877. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3181d34114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaur J, Reddy K, Balakumar P. The novel role of fenofibrate in preventing nicotine and sodium arsenite-induced vascular endothelial dysfunction in the rat. Cardiovasc Toxicol. 2010;10:227–238. doi: 10.1007/s12012-010-9086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocsis GF, Pipis J, Fekete V, Kovács-Simon A, Odendaal L, Molnár E, et al. Lovastatin interferes with the infarct size-limiting effect of ischemic preconditioning and postconditioning in rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2008;294:H2406–H2409. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00862.2007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koh KK, Quon MJ, Han SH, Chung WJ, Ahn JY, Seo YH, et al. Additive beneficial effects of fenofibrate combined with atorvastatin in the treatment of combined hyperlipidemia. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2005;45:1649–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonhardt W, Pfützner A, Müller J, Pietzsch J, Forst T, Karagiannis E, et al. Effects of pioglitazone and/or simvastatin on low density lipoprotein subfractions in non-diabetic patients with high cardiovascular risk: a sub-analysis from the PIOSTAT study. Atherosclerosis. 2008;201:155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2008.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li X, Liu XP, Liu XH, Du X, Kang JP, Lü Q, et al. Effect of statin therapy on mortality in patients with non-ischemic dilated cardiomyopathy. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2010;90:1974–1977. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu B, Chen M, Peng HX, Zhang C, Ou ST. Effects of atorvastatin on expression of peroxisome proliferation activated receptor gamma in unilateral ureteral obstruction in rats. Zhongguo Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue. 2007;19:739–741. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masumoto A, Hirooka Y, Hironaga K, Eshima K, Setoguchi S, Egashira K, et al. Effect of pravastatin on endothelial function in patients with coronary artery disease (cholesterol-independent effect of pravastatin) Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:1291–1294. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(01)02090-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhtar RY, Reckless JP. Statin-induced myositis: a commonly encountered or rare side effect? Curr Opin Lipidol. 2005;16:640–647. doi: 10.1097/01.mol.0000188414.90528.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murdock DK, Jansen D, Juza RM, Kersten M, Olson K, Hendricks B. Benefit of adding pioglitazone to statin therapy in non-diabetic patients with the metabolic syndrome. WMJ. 2006;105:22–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nissen SE, Wolski K. Effect of rosiglitazone on the risk of myocardial infarction and death from cardiovascular causes. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:2457–2471. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa072761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata T, Miyauchi T, Sakai S, Irukayama-Tomobe Y, Goto K, Yamaguchi I. Stimulation of peroxisome-proliferator-activated receptor alpha (PPAR alpha) attenuates cardiac fibrosis and endothelin-1 production in pressure overloaded rat hearts. Clin Sci. 2002;103:284S–288S. doi: 10.1042/CS103S284S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogata T, Miyauchi T, Sakai S, Takanashi M, Irukayama-Tomobe Y, Yamaguchi I. Myocardial fibrosis and diastolic dysfunction in deoxycorticosterone acetate salt hypertensive rats is ameliorated by the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-alpha activator fenofibrate, partly by suppressing inflammatory responses associated with the nuclear factor-kappa-B pathway. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:1481–1488. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2003.11.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onody A, Zvara A, Hackler L, Jr, Vígh L, Ferdinandy P, Puskás LG. Effect of classic preconditioning on the gene expression pattern of rat hearts: a DNA microarray study. FEBS Lett. 2003;536:35–40. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(03)00006-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paumelle R, Blanquart C, Briand O, Barbier O, Duhem C, Woerly G, et al. Acute antiinflammatory properties of statins involve peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor-alpha via inhibition of the protein kinase C signaling pathway. Circ Res. 2006;98:361–369. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000202706.70992.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qin YW, Ye P, He JQ, Sheng L, Wang LY, Du J. Simvastatin inhibited cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice fed a ‘Western-style diet’ by increasing PPAR α and γ expression and reducing TC, MMP-9, and Cat S levels. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2010;31:1350–1358. doi: 10.1038/aps.2010.109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravingerová T, Adameová A, Kelly T, Antonopoulou E, Pancza D, Ondrejcáková M, et al. Changes in PPAR gene expression and myocardial tolerance to ischaemia: relevance to pleiotropic effects of statins. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 2009;87:1028–1036. doi: 10.1139/Y09-071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rinaldi B, Donniacuo M, Esposito E, Capuano A, Sodano L, Mazzon E, et al. PPARα mediates the anti-inflammatory effect of simvastatin in an experimental model of zymosan-induced multiple organ failure. Br J Pharmacol. 2011;163:609–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.2011.01248.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roglans N, Sanguino E, Peris C, Alegret M, Vázquez M, Adzet T, et al. Atorvastatin treatment induced peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha expression and decreased plasma nonesterified fatty acids and liver triglyceride in fructose-fed rats. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2002;302:232–239. doi: 10.1124/jpet.302.1.232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanguino E, Roglans N, Alegret M, Sánchez RM, Vázquez-Carrera M, Laguna JC. Atorvastatin reverses age-related reduction in rat hepatic PPARalpha and HNF-4. Br J Pharmacol. 2005;145:853–861. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0706260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schernthaner G, Chilton RJ. Cardiovascular risk and thiazolidinediones–what do meta-analyses really tell us? Diabetes Obes Metab. 2010;12:1023–1035. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2010.01262.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Y, Wu H, Wang C, Shao H, Huang H, Jing H, et al. Simvastatin attenuates cardiopulmonary bypass-induced myocardial inflammatory injury in rats by activating peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ. Eur J Pharmacol. 2010;649:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2010.08.058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng L, Ye P, Liu YX. Atorvastatin upregulates the expression of PPAR alpha/gamma and inhibits the hypertrophy of cardiac myocytes in vitro. Zhonghua Xin Xue Guan Bing Za Zhi. 2005;33:1080–1084. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugamura K, Sugiyama S, Matsuzawa Y, Nozaki T, Horibata Y, Ogawa H. Benefit of adding pioglitazone to successful statin therapy in nondiabetic patients with coronary artery disease. Circ J. 2008;72:1193–1197. doi: 10.1253/circj.72.1193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonstad S, Retterstøl K, Ose L, Ohman KP, Lindberg MB, Svensson M. The dual peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor alpha/gamma agonist tesaglitazar further improves the lipid profile in dyslipidemic subjects treated with atorvastatin. Metabolism. 2007;56:1285–1292. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2007.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treasure CB, Klein JL, Weintraub WS, Talley JD, Stillabower ME, Kosinski AS, et al. Beneficial effects of cholesterol-lowering therapy on the coronary endothelium in patients with coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:481–487. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199502233320801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu J, Song Y, Li H, Chen J. Rhabdomyolysis associated with fibrate therapy: review of 76 published cases and a new case report. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 2009;65:1169–1174. doi: 10.1007/s00228-009-0723-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L, Lin P, Xie H, Xu C. Effects of atorvastatin and losartan on monocrotaline-induced pulmonary artery remodeling in rats. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2010;32:547–554. doi: 10.3109/10641963.2010.503295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yano M, Matsumura T, Senokuchi T, Ishii N, Murata Y, Taketa K, et al. Statins activate peroxisome proliferators-activated receptor gamma through extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 and p38 mitogen-activated protein kinase-dependent cyclooxygenase-2 expression in macrophages. Circ Res. 2007;100:1442–1451. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000268411.49545.9c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye P, Sheng L, Zhang C, Liu Y. Atorvastatin attenuating down-regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma in preventing cardiac hypertrophy of rats in vitro and in vivo. J Pharm Pharm Sci. 2006;9:365–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zambon A, Cusi K. The role of fenofibrate in clinical practice. Diab Vasc Dis Res. 2007;4:S15–S20. doi: 10.3132/dvdr.2007.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zelvyte I, Dominaitiene R, Crisby M, Janciauskiene S. Modulation of inflammatory mediators and PPARgamma and NFkappaB expression by pravastatin in response to lipoproteins in human monocytes in vitro. Pharmacol Res. 2002;45:147–154. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2001.0922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]