Abstract

This is an exploratory study that examined verbal aggression in romantic relationships among unmarried Black and White women and men as a function of gender and race. We employed an ecological approach to examine the receipt of verbal aggression separately for men and women at the levels of individual, relationship, and community. We also explored whether gender-specific correlates of verbal aggression interacted with race. Analyses were based on a sample of 212 women and 133 men in non-marital romantic relationships recruited from 21 U.S. cities for a larger study. Linear mixed-effects models revealed that factors related to experiencing verbal aggression differed substantially for unmarried women and men in romantic relationships. Interesting racial differences also emerged distinctly for women and men.

Keywords: ecological approach, gender, partner violence, race, verbal aggression

Verbal aggression in non-marital romantic relationships is an understudied area of intimate partner violence. Our current knowledge of domestic abuse comes primarily from studies focused on physical violence, although abuse is manifested in a variety of forms, including the use of words to hurt or intimidate. As a much more frequently reported form of intimate partner violence (Straus & Sweet, 1992), verbal aggression has been identified as a significant predictor of later episodes of physical violence (Schumacher & Leonard, 2005; Stets, 1990). Stets (1990) suggested that people are typically verbally aggressive before they engage in physically violent behaviors. In addition, its impact on the victim’s well-being may be just as detrimental as, or even more so than, physical aggression (Vissing, Straus, Gelles, & Harrop, 1990). Despite the documented relevance and significance of verbal aggression in intimate partner relationships, little is known about who might be at risk of experiencing such aggression and what factors might be protective.

Another limitation of previous research is that the few studies that have addressed verbal aggression have examined it only within the context of either legal marriage (e.g., Schumacher & Leonard, 2005) or romantic partnerships at large that mixed marital and non-marital relationships with no distinction of marital status (e.g., Dutton, Kaltman, Goodman, Weinfurt, & Vankos, 2005). Thus, we know even less about verbal aggression in non-marital romantic relationships, such as cohabiting or dating couples. When compared to married couples, such relationships are distinguished by their temporary nature (Waite, 1999), lower commitment (Nock, 1995), poorer relationship quality (Brown & Booth, 1996), and lower social integration (Nock, 1995). Together with evidence for higher levels of physical violence among cohabitating (Yllo & Straus, 1981) and dating couples (Stets & Straus, 1989) than married couples, these attributes suggest that in order to better understand verbal aggression in non-marital relationships one must examine this relational context as a unique entity separate from marriage (Brownridge & Halli, 2002). According to the report from the U.S. Census Bureau (Simmons & O’Connell, 2003), a total of 5.5 million unmarried couples lived together in 2000. This is a 72% increase from 1990, which amplifies the urgency to identify risk factors for greater verbal aggression in this distinctive, yet increasingly pervasive, domestic arrangement.

Finally, we do not know whether some risk markers of experiencing verbal aggression differ on the basis of gender or race. For example, with respect to gender, cultural expectations for men to be the economic provider might place financially disadvantaged men, compared to economically deprived women, at an increased risk of being subject to coercive verbal treatments by their partners. In this light, it is important for researchers to assess whether and how these associations might be similar or different for women and men. Additionally, different sociocultural realities for Blacks as compared to Whites suggest that it might be worth examining the role of race in the link between gender and verbal aggression. Studies have found no differences between Black and White couples overall in the rate of verbal aggression (Solari & Baldwin, 2002; Stets, 1990). However, when assessed separately for males and females, being Black was significantly associated with more frequent perpetration of verbal aggression for females only (Stets, 1990). Despite the evidence for these within-gender racial differences, we do not know what factors are associated with verbal aggression among different groups. We suspect that there might be racially distinct risk factors operating for men versus women. Few studies have conducted these within-group analyses among adults in non-marital relationships due in part to sample sizes that were inadequate to allow for separate analyses to obtain reliable results.

In an attempt to address the aforementioned limitations in research, we conduct an exploratory study by examining various factors related to partner’s use of verbally aggressive tactics among unmarried Black and White adults who are romantically involved with an opposite-sex partner. In particular, we explore multiple variables that might be associated for men and women separately at the levels of individual, relationship, and community as informed by an ecological approach to partner violence (Carlson, 1984; Heise, 1998; Dahlberg & Krug, 2002). We also seek to identify risk factors at each level that may be universal across gender as well as those that might be racially distinct for each group.

Conceptual framework: An ecological approach

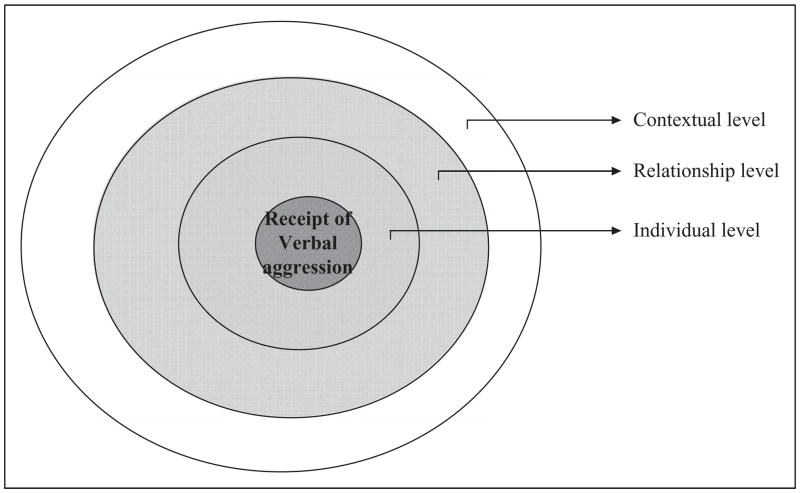

An ecological approach to partner violence guided the present study. This approach has its theoretical origin in Bronfenbrenner’s ecological theory of human development (1986), which posits that human experiences are embedded in, and shaped by multiple layers of contexts that are interrelated. Thus, according to Bronfenbrenner, it is important to examine how various factors at multiple levels of one’s environment influence the phenomenon of interest. As such, an ecological approach to partner violence emerged in recognition that extant theories had tended to emphasize only a single dimension of the social environment in understanding partner violence (Heise, 1998). For instance, feminist theories tended to present patriarchy as the main cause of domestic violence (e.g., Dobash & Dobash, 1979) while resource theory focused on one’s social or economic status as explanatory (e.g., Goode, 1971). In this regard, what sets an ecological approach apart from other theories is its conceptualization of partner violence as situated within multiple facets of one’s social environment (Carlson, 1984). This perspective posits that a more holistic understanding of partner violence requires examining interrelationships between partner violence and a wide range of factors including individual as well as contextual correlates. Although several ecological models of partner violence have been proposed (e.g., Carlson, 1984; Heise, 1998; Dahlberg & Krug, 2002), none have specifically addressed verbal aggression and very few have actually tested a proposed model empirically (e.g., Flake, 2005).

In the present study, we integrate and refine previous ecological models (see Figure 1). We ensure that the variables examined in this study are multiple indicators of individual, relationship, and community dimensions in one’s social environment as shown in Figure 1. First, located at the innermost circle is the individual level. This level is comprised of what each person brings with him or her to the intimate partner relationship, including demographic characteristics (e.g., age, education) as well as individual psychosocial well-being and personal resources. The second layer depicts the relationship level, which is the very setting where violence between intimate partners takes place. At this level, we examine factors that characterize a person’s relationships with others in his or her social network. These factors include, but are not limited to social support, the importance of one’s current romantic relationship, and congruency between the couples in a range of respects (e.g., race, education). Third, the community level encompasses structural features of the geographic area in which a person resides, such as employment and poverty rate in one’s community.

Figure 1.

Ecological model

Because there is a paucity of studies that specifically examined verbal aggression as a core outcome variable in any relational context, the present investigation is exploratory in nature rather than hypothesis testing. Our variable selection is influenced heavily by findings from research on physical violence in couple relationships. In addition, we explore a number of variables that have not been previously linked to physical or verbal aggression despite the evidence suggesting that there might be a potential relationship. Further, it seems plausible that some of the factors contributing to physical as compared to verbal aggression may be distinctive, so we cite studies that are suggestive of such differentiation. Taken together, our exploratory model is comprised of newly proposed as well as previously examined predictors of physical and/or verbal aggression at each ecological level. By doing so, we seek to shed light on the understudied topic of verbal aggression in non-marital intimate relationships.

Individual-level factors

Three categories make up the individual level of analysis in this paper. These categories include demographics, psychological resources, and economic resources. Under the category of demographic factors relevant to verbal aggression, we considered age, socioeconomic status (SES), and race. Though not consistent, these factors have been shown to impact victimization from partner violence. For instance, among dating couples, low SES was associated with physically violent victimization by partners (Lewis & Fremouw, 2001) while in cohabiting relationships, more highly educated women were at risk of experiencing physical violence (Brownridge & Halli, 2002). Women’s younger age was associated with men’s greater use of verbally aggressive tactics towards their female partners in a sample of married and cohabiting couples combined (Straus & Sweet, 1992). Being Black was also significantly associated with more frequent perpetration of verbal aggression for females (Stets, 1990) although the overall rate of verbal aggression seems similar across Black and White couples (Solari & Baldwin, 2002; Stets, 1990).

Psychological resources have also been linked with partner violence. Higher levels of depressive symptoms have been associated with more physically aggressive episodes among cohabitors (Stets, 1991). Low self-esteem has also been regarded as a risk factor for being physically victimized in dating context (see Lewis and Fremouw, 2001) as well as in cohabiting and marital relationships (Salari & Baldwin, 2002). A possible gender difference has been noted for physical aggression in that low self-esteem is a significant risk factor only for females but not for males (O’Keefe & Treister, 1998; Salari & Baldwin, 2002), whereas both men and women’s low self-esteem emerged as a significant predictor of verbal aggression among a nationally representative sample of cohabiting and married couples (Salari & Baldwin, 2002). Although low life satisfaction and loneliness are indicators of low psychological well-being like depression, the possibility that they may place individuals at risk of experiencing verbal aggression from their partners has not been explored. In this study, we expect that individuals who are less satisfied with their lives and lonely would be more likely to become a target of partner’s verbal aggression. Further, we speculate that individuals with low levels of psychological resources as measured by perceived alternative for potential mates and perceived self-attractiveness would feel less optimistic and confident about the prospective of finding another partner if things go wrong in the current relationship. Thus, they may be more tolerant of their partners’ verbal aggression towards them and stay in the relationship.

What we know about the role of women’s economic resources and receipt of partner violence mainly comes from research on physical partner violence, which provides mixed findings. Tolman and Rafael (2000) found that women on welfare reported experiencing more frequent episodes of physical abuse than non-recipients. Increased maternal employment among women in welfare to work programs, however, decreased subsequent reports of experiencing abuse (Gibson-Davis, Magnuson, Gennetian, & Duncan, 2005). Working women living with their partner were at greater risk of experiencing physical violence than their non-working counterparts (Brownridge & Halli, 2002), but others did not find women’s employment status to be significantly associated with a recent incident of physical domestic violence (Tolman & Rosen, 2001). By having multiple indicators of economic resources, such as personal income, receipt of welfare, and work status, the present study attempted to see if verbal aggression is related to each of these different markers of economic status that have previously predicted physical violence.

Relationship-level factors

While several relationship-level factors were identified to be related to couple aggression, there is evidence that their effects may vary by marital status and the type of aggression. For instance, Stets (1991) found that lack of social support as indicated by having no ties to groups and organizations among cohabitors was related to increases in violent episodes, whereas Salaris and Baldwin (2002) found that married or cohabiting couples were more verbally aggressive when they engaged in more frequent social outings. Importance of relationship may also have differential effects. Stets (1991) found that having weak ties to spouse or partner created greater physical aggression. On the other hand, a serious relationship was a significant predictor of physical victimization for females in dating relationships but not for males (O’Keefe & Treister, 1998). These contrasting findings suggest that separate analyses by marital status or gender are needed to clarify whether these factors are equally significant for unmarried men and women in relationships. Moreover, evidence for racial differences in relationship orientation, such as commitment (Kurdek, 2008), suggests that relationship-level factors may have racially distinct implications for verbal aggression.

In addition, drawing from research suggesting that individuals in racially heterogamous marriages are less happy and more likely than individuals in homogamous marriages to divorce (Heaton, 2002), we expect that individuals in relationships with partners of a different racial background would experience more verbal aggression than do those in racially homogamous relationships. Further, given the evidence that partner’s economic profile (male partner’s profile more consistently than the female partner’s), such as income and employment status, is a significant factor that contributes to cohabiting couples’ decision to get married (Smock, Manning, & Porter, 2005), we speculate that the extent of individuals’ satisfaction with partner’s earning may have implications for their experience of verbal aggression in the relationship.

Community-level factors

In recent years, several scholars have recognized that for a more sophisticated conceptualization of partner violence, research requires greater attention to the role of the community-level determinants of intimate partner violence (Browning, 2002). As a result, there is an emerging body of empirical investigations that considers the broader community characteristics associated with partner violence (e.g., Browning, 2002). However, many of these studies have relied on census tract information to assess more macro-level structural characteristics of the neighborhood context while overlooking the effects of more proximal markers of the context, such as perceived neighborhood cohesion and crime. In the present study, we incorporated both distal and proximal contextual factors into the community level of our ecological model in order to better understand the role of the community context in partners’ verbal aggression. Evidence suggests that both of these types of factors are related to uses of physical violence in couple relationships. For instance, higher rates of physical violence have been linked with social cohesion of the neighborhood as perceived by individuals (Browning, 2002) and high neighborhood disadvantage based on the census tract data, including low education and high levels of population density, single parent households, percentage of non-White, racial heterogeneity, unemployment, poverty, and receipt of public assistance (Van Wyk, Benson, Fox, & DeMaris, 2003). Raghavan, Mennerich, Sexton, and James (2006) also found that women’s exposure to neighborhood crime, such as street violence and other criminal activities, significantly increased their risk of experiencing physical violence from their male partners. Further, there is evidence that a low sex ratio in the community (i.e., more women than men) may be associated with greater likelihood of experiencing physical violence among women because lack of potential mates for women may place them in a vulnerable position where they may be more dependent on their current partners. As a result, it may create power imbalance between men and women, leading to greater likelihood of female victimization (Vandello, 2007). By examining verbal aggression at the community level, the current study aims to deepen our knowledge about the role of these contextual factors in partner violence.

Overall, the review of research suggests that we know very little about what is associated with partner verbal victimization. Most studies have examined physical violence alone and arbitrarily combined married and unmarried individuals, thus it is not clear whether previously identified correlates of physical violence are also relevant to verbal violence in non-marital relationships. Moreover, research provides evidence that the correlates of partner violence may differ by gender. Thus, we propose an exploratory ecological model of verbal victimization rather than testing a set of hypotheses. In this exploratory study, we examine whether relationships between the frequency of experiencing verbal aggression and proposed indicators of individual-, relationship-, and/or community-level factors vary by race among males and females in order to determine if there are racially specific risk factors for each gender group. Men and women, and Blacks and Whites may occupy different social locations and thus reside in different ecological contexts. Likewise, it is important to identify gender- and within-gender racially specific associations between verbal aggression and various ecological factors.

Research questions

On the basis of the literature, we formulated the following research questions:

Does the proposed ecological model predict partner’s verbal aggression in non-marital relationships for men and women?

Are there gender-specific factors related to partner’s verbal aggression?

Do associations between the partner’s verbal aggression and independent variables in each gender-specific model vary by race? How?

Method

Sample and procedures

The data used in this study are from the Survey of Families and Relationships (Tucker & Mitchell-Kernan, 1997), which is a longitudinal study with two telephone interviews: the first interviews were conducted from August 1995 through January 1996 and the second were obtained from May 2002 through April 2003. The initial study included a representative sample of 3407 residents of 21 U.S. cities, age 18–55. The cities, with populations of at least 100,000, were selected to represent a range of specific community-level variables, including population characteristics, such as size, ethnic proportions, and sex ratio, as well as indicators of economic climate. Blacks and Whites were interviewed in all 21 cities, and Mexican Americans were interviewed in three western sites. The interview response rate for the Time 1 total sample (i.e., percentage of selected, eligible respondents interviewed) was 79.3% – a very high rate for an all-urban study.

A total of 1993 respondents completed the second interview. The response for Time 2 was 58.6%. Field activities at both time points, including sampling and interviewing, were carried out by the Survey Research Center of the University of Michigan. Sampling at Time 1 was conducted at the city level, excluding suburbs and geographic areas not located within city boundaries.

Data obtained at Time 1 were not used in this study because verbal aggression measures were only obtained at Time 2. Thus, to get the sample for the current study, we eliminated those who were married (n = 1033) and neither married nor in romantic relationships (n = 607) at Time 2 from the Time 2 sample of 1993 respondents. Also, in order to focus exclusively on verbal aggression, three of the unmarried respondents in romantic relationships who had reported physical violence at Time 2 were excluded from the analyses. Two of these respondents had also reported verbal aggression by their partners at Time 2. Physical violence was assessed by asking, “ In the past year, did your partner ever physically hurt you?” As a result, the sample for the current study consisted of 345 Black and White men and women who were not legally married but romantically involved with someone of the opposite sex at Time 2 reporting only verbal aggression by their partners. There were too few Mexican American respondents at Time 2 (n = 5) who met the sample requirement to be included in the analyses for this study.

There was no statistical difference in terms of the age and education level across males and females in the current study sample. The average age was 34.30 (SD = 10.15) for males and 35.14 (SD = 9.83) for females. The average number of years in school was 14.42 (SD = 2.24) for male and 14.25 (SD = 2.27) for female. Men made significantly higher income (Mean = US$42,258.46, SD = US$41,859.82) than women (Mean = US$32,715.76, SD = US$29,779.87). The level of received verbal aggression did not vary by gender (Meanmale = 2.11, SDmale = 1.30; Meanfemale = 2.03, SDfemale = 1.25).

Measures

The overall focus of the Survey of Families and Relationships (Tucker & Mitchell-Kernan, 1997) where the data used in the current study came from was changing trends in family formation and the psychological and socio-structural variables that contributed to family formation attitudes and behaviors. As such, domestic violence was not a primary concern and was not even assessed in the initial data collection. However, though the ability to greatly revise or increase the size of the Time 2 instrument was limited, we felt that some rudimentary indicator of domestic abuse was needed – especially as a factor to be examined in whether or not romantic relationship continued. A brief assessment of partner’s use of verbally aggressive tactics was therefore included. One question was obtained from the HITS Scale (Sherin, Sincore, Li, Zitter, & Shakil, 1998) which is a short screening instrument: (1) In the past year, has your partner ever insulted or talked down to you? (2) In the past year, did your partner ever scream, yell, or curse at you in a hurtful way? In the current study, we used the second item to measure verbal aggression. If a recipient is quick-tempered or sensitive, he or she may often feel insulted by what the partner says. On the other hand, cursing or yelling has less room for such a subjective misappraisal. A score of 0 was given if a respondent answered no to the second item. If a respondent said yes, we then asked to indicate how often it had happened in the last year on a scale of 1 to 5 where a score of 1 was assigned when the respondent reported “ only once or twice,” 2 for “ three to five times,” 3 for “ six to ten times,” 4 for “ 11 to 20 times,” and 5 for “ more than 20 times.”

Three categories of measures are described below: individual-level variables, relationship variables, and contextual indicators.

Individual-level variables

Our indicator of education was a categorical variable that combined total years of education with the highest degree reported. The resulting variable ranged from 10 years for persons who had not completed high school to 20 years for persons who had earned advanced degrees. The age variable was reported age at last birthday.

Personal income was measured by the item “ About how much income did you make in 2001 before taxes, that is, what is the amount of money that you alone made last year? Please include all sources of income, including salaries, wages, social security, welfare and any other income you received in 2001. A “ fold-out” allowed respondents who did not wish to report a specific dollar amount to provide a broader estimate of their income (e.g., would it be greater than US$30,000; greater than US$40,000). For welfare status, we asked each respondent a yes-or-no question, “ Since January 2002, have you received income or support from any public assistance program, for example: food stamps, TANF, SSI, public housing or other welfare programs?” We also assessed whether a respondent stays home or not. For work status, we asked each respondent whether they were employed (coded as 1) or unemployed (coded as 0) at the time of the survey.

To assess psychological resources, we included six measures of depression, self-esteem, loneliness, perceived self-attractiveness, perceived alternatives for potential mates, and life satisfaction. Depression was measured by the 12-item version of The Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) developed by Ross, Mirowsky and Huber (1983). In this study, the alpha reliability for the 12-item CES-D was .91 for women, .90 for men, .90 for Blacks, and .90 for Whites. We used a six-item measure of the self-acceptance aspect of self-esteem which employs items from the Rosenberg (1965) Self Esteem scale and was used in the National Survey of Black Americans (Jackson, Tucker, & Gurin, 1979). Reliability for this scale ranged from .70 (Black men) to .80 (White women).

To measure loneliness, we used a short version of the revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell, Peplau, & Cutrona, 1980). The short version consisted of four items, including “ There is no one I can turn to”, “ I am no longer close to anyone”, and “ I feel left out.” In this study, the alpha reliability was .81 for women, .84 for men, .78 for Blacks, and .84 for Whites.

We used a single-item measure of life satisfaction (“ In general, how satisfied are you with your life as a whole these days? Would you say very satisfied, somewhat satisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, or very dissatisfied?) as used in the National Survey of Black Americans (Jackson et al., 1987). Perceived mate availability was assessed with one item that asked whether or not the respondent felt that there were enough potential partners for her/him: For someone like yourself, that is, someone about your age with a similar educational and social background, are there enough potential partners? Responses were scored on a 10-point scale with 1 meaning not nearly enough and 10 meaning more than enough potential partners for the participants. Perceived personal attractiveness was measured by the item: Now with 1 meaning not attractive at all and 10 meaning extremely attractive, how attractive do you think (men/women) find you?

Relationship-level variables

Social support was measured by three items from The Provision of Social Relations Scale (Turner, 1992), assessing perceived family support (“ no matter what happens, I know that my family will always be there for me should I need them”), the existence of a confidante (“ I have at least one friend or family member I could tell anything.”), and companionship (“ When I want to go out and do things, I have someone who would enjoy doing these things with me.”). These items evidence a fair degree of internal consistency (i.e., as indicated by alphas ranging from .50 to .54).

Importance of relationship was assessed by asking, “ On a scale of 1 to 10, how important is your current relationship to you?” Partner racial homogamy was indicated as follows: couples of the same race/ethnicity were coded “ 0” and couples of different race/ ethnicity were coded “ 1.” The respondents’ satisfaction with his/her partner’s earning was measured by asking, “ On a scale of 1 to 10, with 1 meaning not happy at all and 10 meaning extremely happy, how happy are you with your partner’s earning power?”

Contextual indicators

The Census Bureau’s 1990 Summary Tape Files (STF) 3 and 4 were the primary sources of Wave 1 distal contextual indicators for each of the 21 cities and ethnic groups included in the study. Two types of data were obtained: (1) population counts for women and men at each age from which sex ratios and population size were calculated and (2) percentage of men and women below poverty. Our measure of average sex ratio was obtained specifically by dividing number of males by a number of females in ages between 18 and 55 and multiplying this number by 100.

For proximate contextual indicators, we assessed neighborhood cohesion by asking on a scale of 1 to 3, “ Would you say that you know most of the people in your neighborhood (1), you know some of the people in your neighborhood (2), or that you know few or none of the people in your neighborhood (3)?” Neighborhood unemployment and crime were also obtained by asking separately on a scale of 1 to 3, “ Would you say that high unemployment (crime) is not a problem (1), somewhat of a problem (2), or a big problem in your neighborhood (3)?”

Data analysis

A series of statistical analyses was conducted in order to separately model between-gender and within-gender (e.g., Black women and White women) correlates of received verbal aggression. First, statistical modeling was carried out for each of the models specified above in order to determine if and how partner’s verbally aggressive behavior was related to socioeconomic and demographic indicators (e.g., gender, age, income, etc.), individual- and relationship-level variables, and community context (e.g., average sex ratios, unemployment levels, neighborhood crime rate, and etc.). Given that our data had a clustered structure where each respondent belonged to one of the 21 cities, the variation of our outcome variable might be due to a random city effect. In this case, a linear mixed model (two-level regression model) was developed to take into account the random effect of cities and to investigate both fixed and random effects. Considering that variable selection cannot be conducted on the linear mixed model by itself, we first performed stepwise regressions to set up a threshold for the inclusion of fixed-effect variables. Based on these selected variables, linear mixed-effects models were developed using backward regression. Marginal R2 statistics were used for assessing the goodness-of-fit of fixed effects (Edwards & Orelien, 2008). Age, education level, and income were forced into each model. Second, interaction terms were selected based on the gender by race main effects models. For instance, if a variable was a statistically significant predictor of verbal aggression for White females but not for Black females or vice versa, an interaction term between race and this variable was entered into the female main effects model in order to examine if the effect varied by race among women. We did not run a simple single model with a men-women interaction term because it is not sufficient to explain all the interactions in the context of variable selection.

Several practical aspects of the survey data analysis were considered. Sample weights were applied to compensate the differential sampling rates. Non-response weights were calculated as adjustment factors to reduce the bias due to outcome missing. The final weight was the product of sampling weight, non-response adjustment factor, and post-stratification adjustment.

Results

Table 1 presents the linear mixed-effects models of the selected variables predicting the verbal victimization for women and men. As shown in Table 1, distinct sets of independent variables were significantly associated with verbal victimization for each gender. Interaction tests with race in each model further demonstrated how the effect of these independent variables varied by race among men and women. Age, income, and education were accounted for in all analyses. In this section, we summarize each model in more detail.

Table 1.

Summary of linear mixed-effects model for selected variables predicting the receipt of verbal aggression from a partner for women (n = 213) and men (n = 132)

| Selected variables | Women | Men |

|---|---|---|

| Individual level: | B (SE) | B (SE) |

| Age | −.12 (.09) | −.50 (.11)*** |

| Personal income | .27 (.20) | −.02 (.09) |

| Education | .11 (.10) | −.19 (.13) |

| Race | .28 (.18) | 1.60 (.61)** |

| Receipt of welfare | −.36 (.28) | .20 (.56) |

| Work status | – | 1.33 (.47)** |

| Whether respondent stays home or not | −.95 (.29)** | – |

| Perceived self-attractiveness | – | .36 (.21) |

| Depression | .22 (.08)** | – |

| Self-esteem | −.52 (.09)*** | – |

| Loneliness | −.38 (.09)*** | – |

| Life satisfaction | – | −.43 (.20)* |

| Perceived alternative for potential mates | −.27 (.08)*** | – |

| Relationship level: | ||

| Perceived social support | −.14 (.09) | −.12 (.12) |

| Whether partner’s race is the same as respondent’s | −.79 (.28)** | −1.27 (.34)*** |

| Happy with partner’s earning | – | .35 (.23) |

| Importance of relationship | – | −.31 (.11)** |

| Contextual indicators: | ||

| Perceived neighborhood cohesion | −.14 (.09) | −.43 (.10)*** |

| Perceived neighborhood crime | −.33 (.11)** | .53 (.16)** |

| Perceived neighborhood unemployment | .43 (.09)*** | – |

| City-level percentage of people below poverty | – | −.61 (.17)*** |

| City-level average sex ratio | .26 (.16) | .47 (.19)* |

| Interactions by race: | ||

| Race × city-level average sex ratio | −.59 (.19)** | – |

| Race × income | −.54 (.20)** | – |

| Race × social support | .79 (.18)*** | – |

| Race × perceived neighborhood crime | .50 (.15)*** | – |

| Race × life satisfaction | – | .69 (.25)** |

| Race × happy with partner’s earning | – | −.57 (.26)* |

| Race × work status | – | −1.86 (.65)** |

| Race × perceived self-attractiveness | – | −.93 (.30)** |

| Intercept | .81 (.16)*** | −.15 (.46) |

| Df | 35 | 25 |

| P | <.0001 | .74 |

p<.05;

p<.01;

p<.001

Women

As displayed in Table 1, women’s receipt of verbal aggression from their male partners was significantly associated with multiple factors at each level of their ecological system. According to Table 1, individual-level factors included being a homemaker (rather than in the work force), perceiving less alternative for potential mates, greater depression, having lower self-esteem, and being lonely. At the relationship level, women who had a partner of a different race reported a significantly greater use of verbally aggressive tactics by their partners. Contextual-level factors such as greater perceived problem with unemployment in neighborhood and fewer perceived problems with crime in neighborhood were significantly related to women’s receipt of verbal aggression.

Racial differences were evident among women as indicated by significant interaction effects of race (see Table 1). For instance, Black women who lived in a city populated by more men than women reported a higher level of verbal aggression from their partners, whereas the opposite effect was found for White women. Income also showed opposite patterns. Specifically, White women with higher income reported experiencing significantly less verbal aggression compared to their lower income counterparts, whereas for Black women higher income was associated with greater verbal aggression. Greater social support was associated with less receipt of verbal aggression only among Black women. Higher levels of perceived problems with crime in one’s neighborhood also predicted White women’s receipt of partner’s verbal aggression but not Black women’s.

Men

As expected, men’s receipt of verbal aggression from their female partners was associated with a distinctly different set of variables than was the case for women (see Table 1). At the individual level, younger age, being White, being unemployed, and being less satisfied with life were significantly associated with verbal victimization among men in non-marital relationships. At the relationship level, men who had a partner whose race was different from them and placed less importance on relationship were more subjected to verbally aggressive tactics by their female partners. Contextual-level correlates included greater perceived problem with neighborhood crime, greater percentage of their city population having incomes below poverty level, and higher city sex ratios (i.e., more men relative to women in cities).

Racial differences were observed between White men and Black men (see Table 1). Perceived lower self-attractiveness among White men and greater self-attractiveness among Black men were associated with greater verbal aggression. Lower life satisfaction was a much stronger predictor of experiencing verbal aggression from a partner for Black men than White men. Unemployment increased the frequency of experiencing verbal aggression for White men, but no such effect was observed for Black men. However, Black men who had a female partner with greater economic power experienced greater verbal aggression, whereas no effect was found for White men.

Discussion

In light of the earlier onset and distinct nature of verbal aggression separate from physical aggression (Schumacher & Leonard, 2005; Stets, 1990), we explored the effect of various factors on verbal aggression experienced specifically in the absence of physical violence, taking an ecological approach to partner violence (Carlson, 1984; Heise, 1998; Dahlberg & Krug, 2002). We found that our exploratory model predicted verbal victimization by partner at the levels of individual, relationship, and community. In addition, separate analyses for each gender showed that the predictive patterns differed for men and women in non-marital romantic relationships as well as by race within each gender group.

The only consistent finding across men and women was that being in an interracial relationship increased the likelihood of experiencing verbal aggression from a romantic partner. Previous research has focused on social challenges that interracial couples encounter, such as stereotypes and lack of relationship approval from family and friends (Karis, 2003; Killian, 2001). While such stressors may strain a couple’s relationship, possibly leading to conflict, not much attention has been paid to understand whether and how partner behavior might be affected by racial heterogamy. In this light, our finding adds to the current understanding of partner behavior in interracial relationships and offers an important area for future research. It may be worth identifying whether perceived level of social and familial stress is greater for individuals in interracial relationships than those in intra-racial relationships and how it might be linked to partner verbal aggression.

Apart from partner racial heterogamy, predictors of experiencing verbal aggression differed substantially for women and men although they both reported similar levels of partners’ verbal aggression. We suggest that the striking gender difference observed in this study may be a function of the sociocultural construction of gender, particularly in light of unequal distribution of power along the axis of gender in both domestic and public realms within the U.S. culture. Prominent among women in the current study was that psychological suffering (i.e., lower self-esteem, being lonely, and greater depressive symptomatology) remained significantly linked to women’s greater verbal victimization in our multivariate model even after controlling for key demographic variables. This association can be understood in terms of the dynamic of power-dependence in relationships (see Cast, 2003). Women are expected to perform household labor (South & Spitze, 1994) and emotional work (Erickson, 2005; Hochschild, 1989), both of which occupy a low status in relationships and are often regarded less valuable than the traditionally masculine roles, such as providing financial security. In general, women do both significantly more than men (Erickson, 2005; Hochschild, 1989; South & Spitze, 1994). However, there is evidence that they are less likely to engage in such tasks when psychologically distressed (Crouter, Perry-Jenkins, Huston, & Crawford, 1989). When men no longer receive care and service due to women’s psychological despair, they may feel that their masculine status is threatened. According to power-dependency theory (see Cast, 2003), these men would use verbally aggressive tactics towards their partners as a way to maintain the degree of power associated with their masculine status in the relationship (which entitles them to receive care and service). Further, lack of women’s psychological resources, such as positive sense of self (as opposed to low self-esteem) and feeling happy (as opposed to feeling lonely and depressed) may place them in an emotionally vulnerable position in the relationship, which renders them less relational power and more dependency on their partners to put up with their partners’ verbally aggressive treatment. Similarly, women who possess psychological resources may feel more empowered to put an end to a verbally aggressive relationship.

Unlike women, men’s receipt of verbal aggression was more related to lack of socio-structural resources at the levels of individual (i.e., being unemployed and being younger) and community (i.e., low perceived neighborhood cohesion, high perceived neighborhood crime, and higher poverty rate). While resource theory asserts that men with less social status and structural resources will rely on controlling tactics, such as verbal aggression, in order to secure power and control in the relationship (Goode, 1971), our finding suggests otherwise that they are at a greater risk of victimization when they violate a male gender norm of providing economic security. Cast’s (2003) conceptualization of power-dependence theory provides a useful frame for understanding this finding. According to Cast (2003), individuals with fewer resources have greater dependence on their partners and they have less power and potential to influence or to change a situation in the relationship if they also have no source of alternative relationships. In this light, it is reasonable to speculate that since structurally disadvantaged men are not desirable candidates for relationship, they have low alternatives for potential mates, thus may be more likely to stay with their verbally aggressive partners. Studies have primarily focused on how sociostructurally deprived men are more likely to act violently towards their partners (e.g., McCloskey, 1996). In this light, our finding adds to the existing research by showing that men with poor sociostructural resources may also be more subject to verbal abuse from their romantic partners. Taken together, these findings suggest that for both men and women, verbally aggressive behaviors in non-marital relationships are motivated in part by the violation of the socioculturally constructed gender ideology.

In addition, the effects of several factors on partner’s verbal aggression for men and women significantly varied as a function of race. Opposite patterns that emerged for Black versus White women suggest even when they occupied comparable contexts (e.g., city-level average sex ratio and perceived neighborhood crime rate), the role of race on the receipt of verbal aggression was apparent. This is contrary to Benson and his colleagues’ (Benson, Wooldredge, Thistlethwaite, & Fox, 2004) observation that the effect of race on male-to-female physical violence disappeared among Whites and Blacks when they lived in similar communities. It will be worthwhile for future research to explain why the effect of community varies by race among women as opposed to men particularly in relation to verbal aggression.

An interesting racial difference among men is also worth noting. Greater receipt of verbal aggression was associated with lower perceived self attractiveness among White men, whereas an opposite direction of effect was found among Black men. We speculate that the differential effect of self-attractiveness may reflect different mate availability contexts for Blacks and Whites. Research suggests that declining marriage rate among Black women can be explained by the shortage of marriageable Black men because of their high mortality and incarceration rate (Bennet, Bloom, & Craig, 1992). It is possible, then, that in the context of the shortage of available Black men unmarried attractive Black men may get more attention from other unmarried Black women. Consequently, the female partners may feel less secure about their relationships and they may be more likely to use verbally aggressive tactics against their men. It is difficult to explain, however, why these attractive but verbally abused Black men do not leave their partners even though they seem to have greater alternatives for other potential mates. It will be useful for future research to further explore how self-attractiveness among unmarried Black men might indeed be related to relationship behavior in the context of the shortage of marriageable Black men in U.S. society. The mate availability context for Black men does not apply to White men in the same way since a decline of marriage among White women is explained by economic deficits of available men in general (Lichter, McLaughlin, Kephart, & Landry, 1992). Thus, we see low self-attractiveness for White men as an indicator of poor self-esteem. Consistent with the literature (e.g., Lewis & Fremouw, 2001; Salari & Baldwin, 2002), those with lower self-esteem in this study were more likely to be victimized by their female partners. Clearly, more research is needed to see if our speculations would be empirically supported and to understand the implications of this racial difference.

The current findings must be interpreted with caution in light of the study’s limitations. First, although our ecological model identified significant correlates of experiencing verbal aggression, it is possible that it did not capture all existing correlates that might be linked to that experience given the exploratory nature of this study. For instance, some variables that have consistently been found to be related to physical violence were not included in this study (e.g., alcohol use). Future research should expand the model as this study has demonstrated that the ecological approach is a promising tool for furthering our understanding of partner violence. Also, the finding that predictive patterns differed for gender and racial groups suggests that more effort is needed to identify gender- and race-specific predictors of partner violence and theorize the differences. Second, it must be noted that our ecological model is not a causal model due to the non-experimental and cross-sectional nature of the data used in this study. It will be beneficial for future studies to follow individuals in non-marital relationships over time to assess whether and in what context the transition occurs from the receipt of verbal aggression to physical violence. Examining both victimization and perpetration will also be useful. In addition, our use of the item to determine if there was physical abuse in the relationship (“ In the past year, did your partner ever physically hurt you?”) was less than ideal. Finally and importantly, using a broad range of verbally aggressive tactics in terms of intensity and frequency will better capture the nature of verbal aggression.

Despite these limitations, the present study demonstrated that even though men and women in non-marital romantic relationships were experiencing verbal aggression by their partners at a similar rate, distinctively different predictors ofsuch experience existed for men and women. Racial differences were apparent as well among men and women. In conclusion, this study contributes to the field of partner violence by taking a holistic approach to the understudied type of partner aggression and suggesting that its implications vary by gender and race in relation to individual, relationship, and contextual factors.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The preparation of this article was in part supported by a postdoctoral fellowship awarded to the first author from the Family Research Consortium IV, which is funded by grant number 5T32 MH019734 (Tucker) from the National Institute of Mental Health. Collection of the survey data research was supported by two grants from the National Institute of Mental Health, RO1MH47434 (Tucker and Mitchell-Kernan) and KO2MH01278 (Tucker), and grant number R01HD39954 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Tucker and Mitchell-Kernan).

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The author(s) declared no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship and/or publication of this article.

References

- Benson ML, Wooldredge J, Thistlethwaite AB, Fox GL. The correlation between race and domestic violence is confounded with community context. Social Problems. 2004;51(3):326–342. [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology. 1986;22(6):723–742. [Google Scholar]

- Brown S, Booth A. Cohabitation and marriage: A comparison of relationship quality. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1996;58(3):668–678. doi: 10.1111/jomf.12813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browning CR. The span of collective efficacy: Extending social disorganization theory to partner violence. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2002;64:833–850. [Google Scholar]

- Brownridge DA, Halli SS. Understanding male partner violence against cohabiting and married women: An empirical investigation with a synthesized model. Journal of Family Violence. 2002;17(4):341–361. [Google Scholar]

- Bumpass LL, Sweet JA. The National Survey of Families and Households. 1987–88. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson BE. Causes and maintenance of domestic violence: An ecological analysis. Social Service Review. 1984;58(4):569–587. [Google Scholar]

- Cast A. Power and the ability to define the situation. Social Psychology Quarterly. 2003;66(3):185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Crouter AC, Perry-Jenkins M, Huston TL, Crawford DW. The influenceof work-induced psychological states on behavior at home. Basic and Applied Social Psychology. 1989;10(3):273–292. [Google Scholar]

- Curtis KT, Ellison CG. Religious heterogamy and marital conflict: Findings from the national survey of families and households. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23(4):551–576. [Google Scholar]

- Dahlberg LL, Krug EG. Violence: A global public health problem. In: Krug E, Dahlberg LL, Mercy JA, Zwi AB, Lozano R, editors. World report on violence and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Dobash RE, Dobash R. Violence against wives: A case against the patriarchy. New York: The Free Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Dutton MA, Kaltman S, Goodman LA, Weinfurt K, Vankos N. Patterns of intimate partner violence: Correlates and outcomes. Violence and Victims. 2005;20(5):483–497. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards LJ, Orelien JG. Fixed-effect variable selection in linear mixed models using R2 statistics. Computational Statistics & Data Analysis. 2008;52(4):1896 –1907. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson R. Why emotion work matters: Sex, gender, and the division of household labor. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67:337–351. [Google Scholar]

- Flake DF. Individual, family, and community risk markers for domestic violencein Peru. Violence Against Women. 2005;11(3):353–373. doi: 10.1177/1077801204272129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson-Davis CM, Magnuson K, Gennetian LA, Duncan GJ. Employment and domestic abuse among low income women. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 2005;67(5):1149–1168. [Google Scholar]

- Goldscheider C, Goldschedier FK. Ethnicity, religiosity and leaving home: The structural and cultural bases of traditional family values. Sociological Forum. 1988;3(4):525–547. Retrieved on July 22, 2009 from http://www.jstor.org/stable/684542.

- Goode WJ. Force and violence in family. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1971;33:624–636. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton TB. Factors contributing to increasing marital stability in the United States. Journal of Family Issues. 2002;23:392–409. [Google Scholar]

- Heaton TB, Pratt EL. The effects of religious homogamy on marital satisfaction and stability. Journal of Family Issues. 1990;11(2):191–207. [Google Scholar]

- Heise LL. Violence against women: An integrated, ecological framework. Violence Against Women. 1998;4(3):262–290. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004003002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochschild AR. The second shift: Working parents and the revolution at home. New York: Viking; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson JS, Tucker MB, Gurin G. National survey of Black Americans, 1979–80. Ann Arbor, MI: Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research; 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Karis TA. How race matters and does not matter for white women in relationships with black men. Journal of Couple and Relationship Therapy. 2003;2:23–40. [Google Scholar]

- Killian KD. Reconstituting racial histories and identities: The narratives of interracial couples. Journal of Marital and Family Therapy. 2001;27:27–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-0606.2001.tb01137.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korn EL, Graubard BI. Analysis of health surveys. New York, NY: Wiley; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Krause N. Welfare participation and self-esteem in later life. The Gerontologist. 1996;36:665–673. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.5.665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kurdek L. Differences between partners from Black and White heterosexual dating couples in a path model of relationship commitment. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships. 2008;25:51–71. [Google Scholar]

- Levin JS, Taylor RJ, Chatters LM. A multidimensional measure of religious involvement for Blacks. The Sociological Quarterly. 1995;36(1):157–173. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis SF, Fremouw W. Dating violence: A critical review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review. 2001;21(1):105–127. doi: 10.1016/s0272-7358(99)00042-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter DT, McLaughlin DK, Kephart G, Landry DJ. Race and theretreat from marriage: A shortage of marriageable men? American SociologicalReview. 1992;57(6):781–799. [Google Scholar]

- McCloskey L. Socioeconomic and coercive power within the family. Gender and Society. 1996;10:449–463. [Google Scholar]

- Neff JA. Exploring the dimensionality of “ religiosity” and “ spirituality” in the Fetzer multidimensional measure. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion. 2006;45(3):449–459. [Google Scholar]

- Nock SL. A comparison of marriages and cohabiting relationships. Journal of Family Issues. 1995;16(1):53–76. [Google Scholar]

- O’Keefe M, Treister L. Victims of dating violence among high school students: Are the predictors different for males and females? Violence Against Women. 1998;4(2):195–223. doi: 10.1177/1077801298004002005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearlin L, Johnson JS. Marital status, life strains, and depression. American Sociological Review. 1977;42:704–715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raghavan C, Mennerich A, Sexton E, James SE. Community violence and its direct, indirect, and mediating effects on intimate partner violence. Violence against Women. 2006;12(12):1132–1149. doi: 10.1177/1077801206294115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton, NJ: Princeton; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Mirowsky J, Haber J. Marriage patterns and depression. American Sociological Review. 1983;48:809–823. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness scale: Concurrent & discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1980;39:472–480. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher JA, Leonard KE. Husbands’ and wives’ marital adjustment, verbal aggression, and physical aggression as longitudinal predictors of physical aggression in early marriage. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2005;73(1):28–37. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.73.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sherin KM, Sinacore JM, Li XQ, Zitter RE, Shakil A. HITS: A short domestic violence screening tool for use in a family practice setting. Family Medicine. 1998;30(7):508–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmons T, O’Connell M. Married-couple and unmarried-couple households 2000: Census 2000 special reports. 2003 Retrieved on January 14, 2008 from www.census.gov/prod/2003pubs/censr-5.pdf.

- Smock PJ, Manning WD, Porter M. “ Everything’s there except money”: How money shapes decisions to marry among cohabitors. Journal of Marriage and Family. 2005;67(3):680–696. [Google Scholar]

- South ST, Spitze G. Housework in marital and nonmarital households. American Sociological Review. 1994;59:327–347. [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE. Cohabiting and marital aggression: The role of social isolation. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1991;53:669–680. [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE. Verbal and physical aggression in marriage. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1990;52:501–514. [Google Scholar]

- Stets JE, Straus MA. The marriage license as a hitting license: A comparison of assaults in dating, cohabiting, and married couples. Journal of Family Violence. 1989;41(2):161–180. [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Sweet S. Verbal/symbolic aggression in couples: Incidence rates and relationships to personal characteristics. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54:346–357. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor RJ, Mattis J, Chatters LM. Subjective religiosity among Blacks: A synthesis of findings from five national samples. Journal of Black Psychology. 1999;25(4):524–543. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM, Rafael J. A review of research on welfare and domestic violence. Journal of Social Issues. 2000;56(4):655–681. [Google Scholar]

- Tolman RM, Rosen D. Domestic violence in the lives of women receiving welfare: Mental health, substance dependence, and economic well-being. Violence Against Women. 2001;7(2):141–158. [Google Scholar]

- Turner RJ. Measuring social support: Issues of concept and method. In: Veiel HOF, Baumann U, editors. The meaning and measurement of social support. New York: Hemisphere; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Tzeng M. The effects of socioeconomic heterogamy and changes on marital dissolution for first marriages. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1992;54(3):609–619. [Google Scholar]

- Van Wyk JA, Benson ML, Fox GL, DeMaris A. Detangling individual-, partner-, and community-level correlates of partner violence. Crime & Delinquency. 2003;49(3):412–438. [Google Scholar]

- Vandello JA. Sex ratios and homicide across the U.S. International Journal of Psychology Research. 2007;1(1):59–80. [Google Scholar]

- Vissing YM, Straus MA, Gelles RJ, Harrop JW. Verbal aggression by parents and psycho-social problems of children. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1990;14:233–238. doi: 10.1016/0145-2134(91)90067-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waite L. The negative effects of cohabitation. The Responsive Community. 1999;10:31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Yllo K, Straus MA. Interpersonal violence among married and cohabiting couples. Family Relations. 1981;30:339–347. [Google Scholar]