Abstract

The integrins are transmembrane receptors for ECM proteins, and they regulate various cellular functions in the central nervous system. In hippocampal neurons, the β3 integrin subtype is required for homeostatic synaptic scaling of AMPA receptors (AMPARs) induced by chronic activity deprivation. The surface level of β3 integrin in postsynaptic neurons directly correlates with synaptic strength and the abundance of synaptic GluA2 AMPAR subunit. Although these observations suggest a functional link between β3 integrin and AMPAR, little is known about the mechanistic basis for the connection. Here we investigate the nature of β3 integrin and AMPAR interaction underlying the β3 integrin-dependent control of synaptic AMPAR expression and thus synaptic strength. We show that β3 integrin and GluA2 subunit form a complex in mouse brain that involves the direct binding between their cytoplasmic domains. In contrast, β3 integrin associates with GluA1 AMPAR subunit only weakly, and, in a heterologous expression system, the interaction requires the coexpression of GluA2. Surprisingly, in hippocampal pyramidal neurons, expressing β3 integrin mutants with either increased or decreased affinity for extracellular ligands has no differential effects in elevating excitatory synaptic currents and surface GluA2 levels compared with WT β3 integrin. Our findings identify an integrin family member, β3, as a direct interactor of an AMPAR subunit and provide molecular insights into how this cell-adhesion protein regulates the composition of cell-surface AMPARs.

Keywords: homeostatic synaptic plasticity, extracellular matrix, excitatory synaptic transmission

Synapses receive, integrate, and transmit information across neural networks, and use-dependent changes in synaptic efficacy are thought to underlie a variety of brain functions from computations to learning and memory. The activity-dependent changes in synaptic properties rely on the coordinated actions of a vast array of molecules in the pre- and the postsynaptic neurons. At excitatory synapses, changes in postsynaptic AMPA receptor (AMPAR) number are crucial for regulating synaptic strength. Insertion and removal of postsynaptic AMPARs contribute directly to some forms of long-term potentiation and long-term depression (1, 2) and to homeostatic synaptic plasticity, which is a compensatory mechanism engaged by neurons in response to chronic changes in network activity (3, 4). Delineating the mechanisms governing the trafficking of AMPARs is a key step toward understanding the basis of functional plasticity at excitatory synapses.

Growing evidence indicates that synaptic cell-adhesion molecules are important players in regulating synaptic plasticity. They bridge pre- and postsynaptic membranes and coordinate morphological and functional synaptic changes across the synaptic cleft (5, 6). In this respect, the integrins are of special interest. They are heterodimers consisting of an α- and a β-subunit, and they mediate cell–ECM and cell–cell adhesions (7). Unlike other cell-adhesion molecules, integrins undergo extensive conformational changes that are coupled to their adhesive state for extracellular molecules (8–11). Low-affinity integrins are in a folded conformation, and they switch to an extended high-affinity form upon binding of either a cytosolic protein, such as talin, to their C terminus (inside-out signaling) or an extracellular ligand to their ectodomain (outside-in signaling). Integrins thus function as bidirectional signaling molecules linking cell adhesion to intracellular events (12). Some integrin subtypes are expressed in the brain and are found enriched at synapses (13). Notably, β1 and β3 integrins are emerging as key regulators of synapse development and maturation (14–16), spine morphology (17), and synapse function at both excitatory and inhibitory synapses (18, 19). In hippocampal neurons, β1 integrins play a role in long-term potentiation (16, 20–22) (for review, see refs. 13 and 18), whereas β3 integrin is involved in stabilizing GluA2-containing AMPARs at synapses and is required for homeostatic synaptic scaling (13, 23–25).

Here we investigate the molecular mechanisms underlying the regulation of synaptic AMPAR expression by β3 integrin. We find that β3 integrin and GluA2 AMPAR subunits colocalize at synapses and interact biochemically in mouse brain. Furthermore, we demonstrate that β3 integrin and GluA2 bind directly to each other involving their cytoplasmic domains. The association between β3 integrin and the other major AMPAR subunit, GluA1, is weaker and indirect, and it requires the presence of GluA2. Interestingly, synaptic AMPAR currents and surface GluA2 levels are not differentially affected upon persistently altering the activation state of β3 integrin. Altogether, our results identify an integrin family member, β3, as a direct interactor of AMPARs and suggest that the level of expression of β3 integrin, rather than its ligand-induced conformational changes, is important for modulating the subunit composition of synaptic AMPARs.

Results

β3 Integrin Is Associated with AMPARs in the Brain.

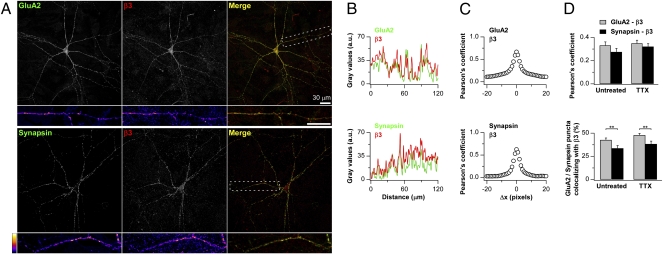

We previously found that the surface levels of GluA2 AMPAR subunits were directly correlated to those of β3 integrin: Exogenously expressing β3 integrin promoted the accumulation of GluA2-containing AMPARs at synapses, and homeostatic synaptic scaling of excitatory synaptic currents induced by chronic activity deprivation, which depended on β3 integrin, accompanied an increase in β3 integrin surface levels (24). To gain insights into the basis of correlation, we first examined the distribution pattern of β3 integrin at excitatory synapses by determining the extent colocalization of GluA2 and β3 integrin in primary hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Endogenous β3 integrin showed punctate appearance along the dendrites with a good degree of colocalization with GluA2 and, to a lower extent, the presynaptic marker synapsin (Fig. 1; percentage synaptic marker punctae positive for β3 integrin: 42.8 ± 2.1% for GluA2 and 33.7 ± 3.0% for synapsin). Chronic tetrodotoxin (TTX) treatment that induced homeostatic synaptic plasticity (see ref. 24) did not significantly alter the percentage colocalization of these synaptic markers with β3 integrin (Fig. 1D; 47.9 ± 1.8% for GluA2 and 38.3 ± 3.0 for synapsin, P > 0.05 relative to controls without TTX treatment for both groups). Therefore, the up-regulation of GluA2 during synaptic scaling involved an increase in surface β3 integrin (24) in a manner that likely maintained the ratio of its synaptic to nonsynaptic distribution, without selectively enriching for β3 integrin at synapses.

Fig. 1.

Endogenous β3 integrin and AMPAR GluA2 subunits colocalize in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. (A) Representative images of cultured neurons double-labeled for surface GluA2 (green) and surface β3 integrin (red; Upper) and synapsin (green) and surface β3 (red; Lower). (B) Plots of fluorescence intensity profiles along the dendrite for the boxed regions in A. (C) Pearson's coefficients for the images in A, indicating high correlation between green and red channels at Δx = 0 (0.67 for β3 integrins and GluA2 and 0.62 for β3 integrin and synapsin). Introducing a shift along the x axis (Δx) between green and red channels sharply reduces the level of correlation, suggesting that the high value of Pearson's coefficient at Δx = 0 represents true colocalization. (D) Summary of colocalization experiments. (Upper) Pearson's coefficient for β3 integrins vs. GluA2 (gray) and vs. synapsin (black) under basal conditions (n = 34 images from four cultures and n = 33 images from five cultures for GluA2 and synapsin labeling, respectively) and upon 2 d of TTX treatment (n = 34 images from four cultures and n = 33 images from five cultures for GluA2 and synapsin labeling, respectively). TTX treatment does not affect the relative extents of colocalization. (Lower) Object-based colocalization analysis showing the percentage of GluA2 (gray) and synapsin puncta (black) colocalizing with β3 integrin puncta under basal conditions and upon 2 d of TTX treatment. As for the Pearson's coefficient analysis, chronic activity deprivation does not affect colocalization levels. Under both basal and TTX-treated conditions, the colocalization with β3 integrin is significantly higher for GluA2 than for synapsin (**P = 0.01).

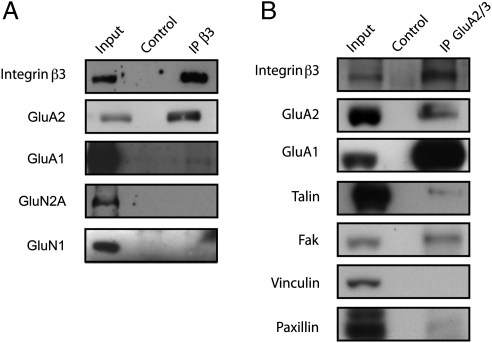

To further investigate the relationship between β3 integrin and GluA2, we tested their biochemical interaction by performing immunoprecipitation assays from adult mouse brain membrane extracts. GluA2 was coimmunoprecipitated with β3 integrin, whereas very little GluA1 was found associated (Fig. 2A). Conversely, β3 integrin was coimmunoprecipitated with GluA2/3 antibody (Fig. 2B). These results show that β3 integrin forms molecular complexes with AMPARs in the brain and that β3 integrin might associate preferentially with GluA2 over GluA1 AMPAR subunit. Notably, the NMDA receptor subunits GluN1 and GluN2A were not detected in the β3 integrin immune pellet, indicating that the interaction with β3 integrin is specific for AMPA over NMDA receptors (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

β3 integrin and AMPAR GluA2 subunit form molecular complexes in adult brain. Western blots of coimmunoprecipitates from adult mouse brain membranes using hamster anti-β3 integrin (A) or rabbit anti-GluA2/3 (B) antibodies. Input lanes show 10% of the total lysate, and control lanes represent nonimmune IgGs for each immunoprecipitation experiment. Although GluA2 subunit coimmunoprecipitates with β3 integrin, very little GluA1 and neither GluN1 nor GluN2A are pulled down. Conversely, β3 integrin is copurified with GluA2/3 subunit along with GluA1, talin, and focal adhesion kinase (FAK).

Integrin-associated proteins focal adhesion kinase (FAK) and talin (26) were also coimmunoprecipitated with GluA2/3 antibody (Fig. 2B), suggesting the possible contribution of GluA2/3 as a component part of integrin signaling clusters in the brain. Note that only trace amount of paxillin and no vinculin were detected in GluA2/3 immune pellets despite their presence in the brain membrane extracts (Fig. 2B). Given that both paxillin and vinculin are known to associate indirectly with β integrins (26), our stringent binding conditions (Materials and Methods) may have precluded the detection of these proteins.

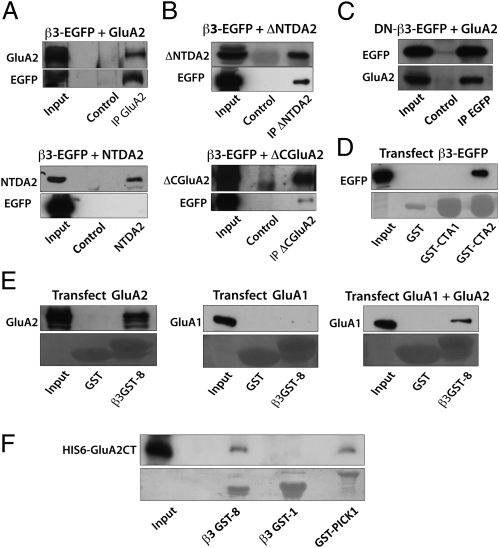

β3 Integrin and GluA2 Interaction Is Direct and Involves Cytoplasmic Domains.

We next sought to determine the protein domains that were important for forming the AMPAR and β3 integrin complex. We first focused on the association between β3 integrin and GluA2 that was robust. We tested the relative contributions of the extracellular and intracellular domains in HEK293 cells by expressing GluA2 deletion mutants (27) with β3 integrin constructs, whose cell-surface expression was previously confirmed in neurons (figure S5 in ref. 24), and by performing coimmunoprecipitation experiments (Fig. 3 A–C). Deleting the GluA2 N-terminal domain (NTD), a large extracellular region crucial for GluA2 binding to another synapse-adhesion protein, N-cadherin (27), did not prevent β3 integrin–GluA2 complex formation (Fig. 3 A and B, Upper). Conversely, no binding was detected when GluA2 NTD alone [fused to the transmembrane domain of PDGF receptor (27)] was expressed with β3 integrin (Fig. 3A, Lower). Moreover, consistent with an apparent lack of requirement for the GluA2 NTD for the β3 integrin interaction, a mutant β3 integrin with its entire ectodomain replaced with EGFP (DN-β3-EGFP), was sufficient to form a complex with GluA2 (Fig. 3C). Notably, GluA2 deleted for the C terminus (i.e., lacking the cytoplasmic tail) but with the intact transmembrane domain immunoprecipitated β3 integrin, although the signal was detectable only after overexposing the blot (Fig. 3B). Collectively, these results strongly suggest that the transmembrane or the intracellular domains of β3 integrin and GluA2 are important for their interaction, whereas their extracellular domains are dispensable.

Fig. 3.

In vitro characterization of β3 integrin–AMPAR interactions. (A) Western blots of immunoprecipitation experiments using anti-HA or anti-myc antibodies from HEK293 cells transfected with EGFP–β3 integrin with either a full-length HA-tagged GluA2 (Upper) or a myc-tagged construct containing only the first 400 aa [NTD domain (NTDA2); Lower]. (B) Western blots of immunoprecipitation experiments with anti-HA antibody from HEK293 cells transfected with EGFP–β3 integrin with HA-tagged GluA2 construct lacking the NTD domain (ΔNTDA2; Upper) or the C terminus (ΔCGluA2; Lower). (C) Western blot showing coimmunoprecipitation using anti-EGFP antibody of full-length HA-tagged GluA2 from lysates of HEK cells coexpressing a β3 integrin mutant with its ectodomain replaced with EGFP (DN-β3-EGFP). (D) Western blot of pull-down experiments from solubilized HEK293 cells expressing EGFP–β3 integrin using the intracellular domain of GluA1 (GST-CTA1), GluA2 (GST-CTA2), or GST control. β3 integrin is pulled down specifically with GST-CTA2 but not with GST-CTA1 or GST alone. (E) Western blots of pull-down assays from extracts of HEK293 cells expressing GluA2, GluA1, or both using GST-tagged β3 integrin C terminus (β3GST-8). Although GluA2 can be pulled down by β3GST-8, GluA1 pull-down requires the coexpression of GluA2. (F) Immunoblots of in vitro pull-down assays of His-tagged GluA2 C terminus using the N-terminal sequence and the cytoplasmic domain of β3 integrin (β3GST-1 and β3GST-8, respectively) and GST-PICK1. Input lanes show 10% of the total lysate (A–E) or purified protein (F) used for each experiment; control lanes represent respective nonimmune IgGs for each immunoprecipitation experiment (A–C). (D–F Lower) Ponceau Red staining of the blot corresponding to image above.

To further explore the potential interaction between the intracellular domains of β3 integrin and AMPAR subunits, pull-down assays with GST-tagged β3 integrin intracellular tail (β3GST-8) were performed with lysates of HEK cells overexpressing full-length GluA1 or GluA2. GluA2 bound strongly to the β3 integrin intracellular tail (Fig. 3E, Left). In contrast, no such interaction was observed for GluA1 (Fig. 3E, Center); GluA1 could be pulled down by the β3 integrin C-terminal tail only when GluA2 was coexpressed (Fig. 3E, Right). In a complementary experiment, the C-terminal domains of GluA1 or GluA2 were used to pull down EGFP-tagged full-length β3 integrin from transfected HEK293 cell lysates (Fig. 3D). Only the C-terminal domain of GluA2, but not that of GluA1, pulled down β3 integrin. Altogether, β3 integrin and GluA1 interaction is indirect and requires the presence of GluA2 AMPAR subunits. Furthermore, our results highlight an important role for the cytoplasmic domains of GluA2 and β3 integrin in forming the β3 integrin–AMPAR complexes.

To test whether the cytoplasmic domains of GluA2 and β3 integrin were sufficient for the interaction between the two proteins, in vitro pull-down assays were performed with purified protein fragments (Fig. 3F). His-tagged GluA2 C terminus was pulled down by GST-tagged β3 integrin C terminus (β3GST-8) but not by GST-tagged β3 integrin N terminus (β3GST-1). The latter fusion protein was used as a control given that the GluA2 intracellular domain and the β3 integrin N terminus derived from the extracellular domain would not interact in vivo. In parallel, His-tagged GluA2 C terminus was also pulled down by GST-PICK1, a known cytoplasmic interactor of GluA2 (28). These observations provide evidence that β3 integrin and GluA2 subunit cytoplasmic domains interact directly.

β3 Integrin Activation State Is Not a Major Determinant in Regulating Excitatory Synaptic Transmission.

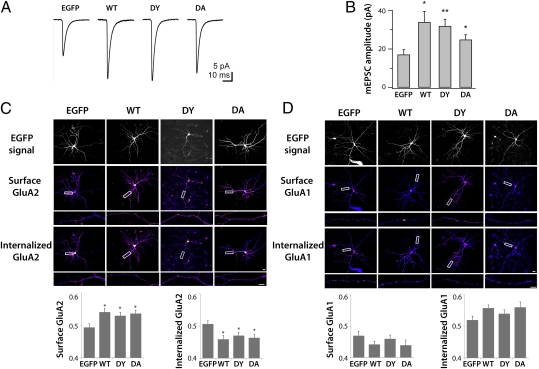

Previously, we have shown that the expression of β3 integrin is an important determinant of excitatory synaptic strength (24). In addition to their level of surface expression, the activation state of integrins can be tightly regulated. For example, various integrins are found on the surface of some cells in an inactive state in which they do not bind extracellular ligands. Extracellular or intracellular signals can activate integrins and convert them into a high-affinity state for binding to the extracellular ligands (7). We have therefore addressed whether the activation state of β3 integrin is relevant for regulating excitatory synaptic strength by making use of β3 integrin point mutants. β3 integrin can be locked in a constitutively inactive or active state by mutating single amino acids: the D119Y mutation in the extracellular domain is constitutively inactive (29), whereas the intracellular D723A mutation results in a constitutively active β3 integrin (30, 31). These point mutants, when overexpressed in HEK cells, could interact with GluA2 (Fig. S1). We next expressed these mutants in hippocampal pyramidal neurons to study synaptic transmission. In agreement with previous results (24), expressing EGFP-tagged WT β3 integrin robustly increased miniature excitatory postsynaptic current (mEPSC) amplitude relative to EGFP-only control (Fig. 4 A and B). Surprisingly, expressing the constitutively active D723A or the inactive D119Y point mutants was just as effective as WT in increasing mEPSC amplitude with no significant differences observed between the three β3 integrin constructs (Fig. 4 A and B; P > 0.05 between WT, D119Y, and D723A; ANOVA). Expression of the constructs had no effect on mEPSC time course as well as frequency (Fig. S2A) and passive membrane properties (Fig. S2B). Because both mutants were trafficked to the dendrites in a manner similar to that in the WT protein (Fig. 4 C and D), these results suggest that increased β3 integrin expression up-regulates synaptic AMPAR currents irrespective of its activation state.

Fig. 4.

Role of β3 integrin activation state in synaptic transmission. (A) Population averages of mEPSC traces from representative hippocampal pyramidal neurons expressing EGFP, EGFP-tagged β3 integrin WT, D119Y constitutively inactive mutant (DY), and D723A constitutively active mutant (DA). (B) Summary of experiments as in A (n = 11 for EGFP, WT, and DA and n = 12 for DY; *P < 0.04; **P = 0.003). Active and inactive β3 integrin point mutants are just as effective as WT β3 integrin in increasing the amplitude of mEPSCs. (C and D) Internalization assays for endogenous GluA2 (C) and GluA1 (D) AMPAR subunits in hippocampal pyramidal neurons transfected with EGFP, WT, D119Y constitutively inactive mutant (DY), and D723A constitutively active mutant (DA) from at least n = 20 images from three independent cultures. (Scale bars: 20 μm.) Surface fraction indicates mean surface fluorescence intensity/total fluorescence intensity (i.e., mean surface intensity + mean internalized intensity). Internalized fraction indicates mean internalized intensity/total fluorescence intensity. *P < 0.01. (Error bars: ±SEM.)

To complement the electrophysiology experiments, we compared the level of intracellular accumulation of endogenous AMPAR subunits by performing an antibody feeding assay in cultured hippocampal neurons transfected with EGFP-tagged WT, D119Y, or D723A β3 integrin (Fig. 4C). The internalization of GluA2 was decreased in cells overexpressing β3 integrin relative to control EGFP neurons irrespective of the β3 integrin activation state, in agreement with the observed changes in mean quantal amplitudes (Fig. 4 A and B). We also extended the analysis to GluA1. Internalized GluA1 levels were not significantly different in neurons transfected with WT or constitutively active or inactive β3 integrin relative to control EGFP neurons (Fig. 4D). Therefore, consistent with the biochemical interaction observed between β3 integrin and GluA2, these findings indicate that β3 integrin preferentially regulates GluA2-containing AMPARs over those containing GluA1 by stabilizing their expression at synapses.

Discussion

This study uncovers β3 integrin as an AMPAR binding partner that regulates postsynaptic expression of AMPARs. We show that β3 integrin and GluA2 subunits interact directly via their respective C termini. Furthermore, β3 integrin–GluA1 interaction is indirect and requires the presence of GluA2 subunits, likely through the formation of heteromeric AMPARs. Interestingly, we find that β3 integrin stabilizes GluA2-containing AMPARs at the cell surface irrespective of its activation state: β3 integrins that are constitutively locked in a ligand-bound or unbound conformation, when overexpressed, reach synapses and are as effective as the WT β3 integrin in increasing excitatory synaptic transmission and reducing GluA2 endocytosis. This finding is surprising because, in a previous study, we found that acute application of arginine–glycine–aspartic acid (RGD)-containing peptides, such as echistatin, promotes GluA2 endocytosis and reduces excitatory synaptic transmission in a β3 integrin-dependent manner on a minutes time scale (24). RGD peptides can, in principle, activate low-affinity state integrins and disrupt existing integrin–ECM interactions by competing with endogenous extracellular ligands (32). The latter effect may have likely predominated in our experimental conditions because we have used high concentrations of RGD peptides when they act as antagonists (33). In agreement with this interpretation, acutely activating endogenous integrins with Mn2+ in cultured hippocampal pyramidal neurons has no effect on mEPSC amplitudes (Fig. S3). Notably, the constitutively active or inactive integrin mutants have been overexpressed in neurons for 1–2 d. Thus, it seems plausible that, although RGD peptides induce AMPAR endocytosis by acutely disrupting integrin–ECM interactions, elevated surface expression of β3 integrin in either WT or mutant forms for a prolonged time reduces AMPAR endocytosis via their interaction to GluA2-containing receptors and stabilizing them at the synapse.

How might β3 integrin stabilize GluA2-containing AMPARs at synapses? Under conditions in which synaptic GluA2 levels are increased, surface β3 integrin levels increase in parallel (24), although both synaptic and nonsynaptic β3 integrins are elevated proportionately (Fig. 1D). Furthermore, unlike many AMPAR-interacting proteins of the postsynaptic density, β3 integrin does not apparently possess a PDZ domain or a PDZ-binding motif (UniProt accession no. O54890), suggesting the possibility that direct binding between GluA2 and β3 integrin may not be used to retain GluA2-containing AMPARs at synapses. Rather, the association may be relevant for trafficking of AMPARs to or away from synapses in that β3 integrin may act as a chaperone. Surface β3 integrin could also act as a gate to control the surface diffusion of GluA2-containing AMPARs, preferentially retarding their diffusion away from synapses, in a manner similar to its function at inhibitory synapses (19). Importantly, whether as a molecular chaperone or as a diffusion barrier, the selective interaction between β3 integrin and GluA2-containing AMPARs is advantageous not only for regulating the abundance of synaptic AMPARs but also for controlling their subunit composition by favoring the recruitment and/or retention of GluA2-containing receptors. Ca2+-permeable AMPARs lacking GluA2 have been suggested to play roles in the expression of long-term potentiation and homeostatic synaptic scaling (34, 35). A better mechanistic understanding of the control of synaptic GluA2 AMPARs by β3 integrin could help gain new insights into how synapses balance different forms of synaptic plasticity.

Cell-adhesion molecules are increasingly acknowledged as key players in regulating synapse function, apart from their accepted roles in synapse development and maturation (18, 36, 37). For example, N-cadherin, one of the best-characterized synaptic adhesion proteins, plays an important role in regulating dendritic spine morphology (38), basal synaptic strength, short-term plasticity, and long-term potentiation (27, 39–42). Although N-cadherin interacts with a cohort of scaffolding proteins, it also binds directly to GluA2 AMPAR subunit (27, 43). Interestingly, in the present study, we identify β3 integrin, a member of a distinct class of adhesion proteins, as another direct interactor of GluA2 AMPAR subunit. Whereas N-cadherin binds to the extracellular NTD of GluA2, β3 integrin binds to its intracellular C-terminal domain and also possibly interact via the transmembrane domain. Thus, in principle, the same AMPAR could simultaneously interact with N-cadherin and β3 integrin, although whether such a tripartite association actually occurs in neurons needs to be tested. More importantly, the interplay between N-cadherin and β3 integrin in regulating excitatory synaptic strength via their direct interaction with GluA2 warrants a closer examination, especially in concert with other protein interactors of GluA2 C terminus with which β3 integrin may compete.

In summary, in contrast to the increasing number of synapse-adhesion proteins such as ephrin B2 (44), neuroligin (45), and LRRTM2 (46) that bind to AMPARs indirectly or as a part of multimolecular complexes, the present study identifies β3 integrin as a direct interactor of AMPARs that plays a role in regulating excitatory synaptic strength. It will be of great interest to determine how different classes of cell-adhesion molecules cooperate to regulate AMPARs and which cues activate their respective signaling pathways to ensure proper control of synaptic strength.

Materials and Methods

DNA Constructs and Antibodies.

Plasmids encoding full-length mouse EGFP-tagged WT β3 integrin and EGFP-tagged β3 integrin single-point mutants D119Y and D723A (31, 47) were provided by Bernhard Wehrle-Haller (University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland). In these constructs, EGFP was fused to the C terminus of β3 integrin. In DN-β3-EGFP, the entire extracellular domain of β3 integrin was replaced by EGFP (24). For details on other DNA constructs and antibodies, see SI Materials and Methods.

Preparation of Mouse Brain Membrane Fractions.

Membrane fractions were prepared from the whole brains of adult C57/BL6 mice as previously described (48). For details, see SI Materials and Methods.

Heterologous Protein Expression in HEK293 Cells and Immunoprecipitation.

HEK293 cells were transfected with plasmids by using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen), and lysates were prepared after 2 d. Soluble extracts were incubated at 4 °C overnight with the appropriate antibody or matching nonimmune control IgGs. Protein G Sepharose (Generon) was added for 90 min at 4 °C. The protein G Sepharose–antibody complexes were washed four times in buffer D or lysis buffer, denatured by boiling in SDS sample buffer, and analyzed by SDS/PAGE followed by immunoblotting. Western blots were visualized with Pierce ECL-detection kit. For details, see SI Materials and Methods.

Pull-Down Assays.

GST or GST-fusion proteins were expressed in Escherichia coli BL21 strain, purified, and coupled with glutathione Sepharose 4B (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech). Soluble extracts from transfected HEK293 cells were incubated overnight at 4 °C with glutathione Sepharose 4B-coupled GST/GST-fusion proteins. After four washes in PBS containing 0.1% Triton X-100, bound proteins were boiled in SDS sample buffer, separated by SDS/PAGE, and analyzed after Western blotting. For in vitro interaction assays, His-tagged GluA2 C terminus was expressed in E. coli BL21 strain and purified with a TALON Cobalt resin (Clontech). Eluted GluA2 C termini were incubated with glutathione Sepharose 4B-coupled GST or GST–β3 integrin fusions or GST-PICK1 for 3 h at room temperature, washed four times with PBS, and analyzed as described above.

Dissociated Neuronal Cultures and Transfections.

Hippocampal neurons were obtained from postnatal day 0 rats and plated onto a glial feeder layer as previously described (24). Cultures were maintained in Neurobasal medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 6 mg/mL glucose, 0.1% MITO serum extender, 2.5% B27, and 2 mM GlutaMAX. For electrophysiology experiments, neurons were transfected with calcium phosphate at 2 d before recording and used for experiments at 10–13 d in vitro (DIV). For imaging experiments, neurons were transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) at 8–9 DIV and imaged at 10–11 DIV.

Electrophysiology.

Whole-cell patch–clamp recordings were performed as previously described (23). For details, see SI Materials and Methods.

Live Labeling of Cell-Surface Receptors and Internalization Assay.

Hippocampal neurons were incubated with antibodies directed against the extracellular domain of either GluA1 (rabbit anti-GluA1, 1:10; Calbiochem) or GluA2 (mouse anti-GluA2, 1:200; Millipore) for 15 min at 37 °C. After a brief wash, neurons were incubated for a further 15 min at 37 °C in Neurobasal medium to allow internalization of surface-labeled receptors. Cells were fixed in PBS containing 4% paraformaldehyde/4% sucrose for 15 min at room temperature. After blocking in 10% FBS/0.1 M glycine PBS, remaining surface receptors were labeled by incubating the cells with Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated secondary antibodies. After a wash in PBS to remove unbound secondary antibodies, neurons were permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 and blocked as before. Internalized receptors were labeled by Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated secondary antibodies. Confocal Z stacks were acquired with an inverted Leica SP5 confocal microscope using a 40× oil-immersion objective and averaging four sequential frames. Z stacks were projected and analyzed with ImageJ (National Institutes of Health).

Immunofluorescence Colocalization Experiments.

Surface expression of GluA2 and β3 integrin was evaluated by live labeling with antibodies directed to the extracellular domains of each protein (mouse anti-GluA2, 1:200; rabbit anti-β3, 1:100; both from Millipore) as previously described (24). After fixation, some neurons were counterstained for synapsin (mouse anti-synapsin, 1:1,000; Synaptic Systems). Confocal stacks were acquired with a 40× oil-immersion objective (N.A. 1.30) with a sequential line-scan mode, 3× scan averaging, and 0.3 μm between optical sections. Confocal images were next analyzed with ImageJ. Each single stack was filtered by using a 3 × 3 pixel-wide median filter, and the maximal fluorescence intensities of in-focus stacks were Z-projected. The resulting images were subsequently thresholded according to their gray level histogram (mode plus six times the SD) and watersheded. Pixel-based (Pearson's coefficient) and object-based colocalization analyses of the preprocessed images were finally performed with the JaCoP plug-in (49).

Statistical Analysis.

Statistical differences were assessed with the one-way ANOVA test followed by the Tukey–Kramer posttest and the paired and unpaired two-tailed Student's t tests, as required (GraphPad Software Inc.). In figures, statistical significance is indicated as follows: *0.05 < P < 0.01; **0.01 < P < 0.001; and ***P < 0.001. Unless otherwise stated, average data are expressed as mean ± SEM.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Myriam Catalano for initial work on this project; Bernhard Wehrle-Haller, Jonathan Hanley, and Yasuyuki Fujita for DNA constructs; Mark Marsh for antibodies; David Elliott for technical assistance; and Yasunori Hayashi, Mathieu Letellier, Andrew McGeachie, and Nathalia Vitureira for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by the Medical Research Council, the Royal Society, European Commission Framework VI EUSynapse Project Grant LSHM-CT-2005-019055 and VII EUROSPIN Project Grant HEALTH-F2-2009-241498, and the RIKEN Brain Science Institute.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1113736109/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Shepherd JD, Huganir RL. The cell biology of synaptic plasticity: AMPA receptor trafficking. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2007;23:613–643. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.23.090506.123516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Choquet D. Fast AMPAR trafficking for a high-frequency synaptic transmission. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:250–260. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07350.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Turrigiano GG, Leslie KR, Desai NS, Rutherford LC, Nelson SB. Activity-dependent scaling of quantal amplitude in neocortical neurons. Nature. 1998;391:892–896. doi: 10.1038/36103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pozo K, Goda Y. Unraveling mechanisms of homeostatic synaptic plasticity. Neuron. 2010;66:337–351. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dalva MB, McClelland AC, Kayser MS. Cell adhesion molecules: Signalling functions at the synapse. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2007;8:206–220. doi: 10.1038/nrn2075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Regehr WG, Carey MR, Best AR. Activity-dependent regulation of synapses by retrograde messengers. Neuron. 2009;63:154–170. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hynes RO. Integrins: Bidirectional, allosteric signaling machines. Cell. 2002;110:673–687. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00971-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takagi J, Petre BM, Walz T, Springer TA. Global conformational rearrangements in integrin extracellular domains in outside-in and inside-out signaling. Cell. 2002;110:599–11. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00935-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liddington RC, Ginsberg MH. Integrin activation takes shape. J Cell Biol. 2002;158:833–839. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200206011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xiong JP, Stehle T, Goodman SL, Arnaout MA. A novel adaptation of the integrin PSI domain revealed from its crystal structure. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:40252–40254. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C400362200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Arnaout MA, Mahalingam B, Xiong JP. Integrin structure, allostery, and bidirectional signaling. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2005;21:381–410. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.21.090704.151217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science. 1999;285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McGeachie AB, Cingolani LA, Goda Y. A stabilising influence: Integrins in regulation of synaptic plasticity. Neurosci Res. 2011;70:24–29. doi: 10.1016/j.neures.2011.02.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chavis P, Westbrook G. Integrins mediate functional pre- and postsynaptic maturation at a hippocampal synapse. Nature. 2001;411:317–321. doi: 10.1038/35077101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hama H, Hara C, Yamaguchi K, Miyawaki A. PKC signaling mediates global enhancement of excitatory synaptogenesis in neurons triggered by local contact with astrocytes. Neuron. 2004;41:405–415. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(04)00007-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Huang Z, et al. Distinct roles of the β1-class integrins at the developing and the mature hippocampal excitatory synapse. J Neurosci. 2006;26:11208–11219. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3526-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shi Y, Ethell IM. Integrins control dendritic spine plasticity in hippocampal neurons through NMDA receptor and Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II-mediated actin reorganization. J Neurosci. 2006;26:1813–1822. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4091-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dityatev A, Schachner M, Sonderegger P. The dual role of the extracellular matrix in synaptic plasticity and homeostasis. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2010;11:735–746. doi: 10.1038/nrn2898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Charrier C, et al. A crosstalk between β1 and β3 integrins controls glycine receptor and gephyrin trafficking at synapses. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:1388–1395. doi: 10.1038/nn.2645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chan CS, et al. β1-integrins are required for hippocampal AMPA receptor-dependent synaptic transmission, synaptic plasticity, and working memory. J Neurosci. 2006;26:223–232. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4110-05.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chun D, Gall CM, Bi X, Lynch G. Evidence that integrins contribute to multiple stages in the consolidation of long term potentiation in rat hippocampus. Neuroscience. 2001;105:815–829. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00173-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kramár EA, Lin B, Rex CS, Gall CM, Lynch G. Integrin-driven actin polymerization consolidates long-term potentiation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103:5579–5584. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601354103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cingolani LA, Goda Y. Differential involvement of β3 integrin in pre- and postsynaptic forms of adaptation to chronic activity deprivation. Neuron Glia Biol. 2008;4:179–187. doi: 10.1017/S1740925X0999024X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cingolani LA, et al. Activity-dependent regulation of synaptic AMPA receptor composition and abundance by β3 integrins. Neuron. 2008;58:749–762. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2008.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yu LM, Goda Y. Dendritic signalling and homeostatic adaptation. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2009;19:327–335. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2009.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harburger DS, Calderwood DA. Integrin signalling at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2009;122:159–163. doi: 10.1242/jcs.018093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saglietti L, et al. Extracellular interactions between GluR2 and N-cadherin in spine regulation. Neuron. 2007;54:461–477. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xia J, Zhang X, Staudinger J, Huganir RL. Clustering of AMPA receptors by the synaptic PDZ domain-containing protein PICK1. Neuron. 1999;22:179–187. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80689-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loftus JC, et al. A β3 integrin mutation abolishes ligand binding and alters divalent cation-dependent conformation. Science. 1990;249:915–918. doi: 10.1126/science.2392682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hughes PE, et al. Breaking the integrin hinge. A defined structural constraint regulates integrin signaling. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6571–6574. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cluzel C, et al. The mechanisms and dynamics of αvβ3 integrin clustering in living cells. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:383–392. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shimaoka M, Springer TA. Therapeutic antagonists and conformational regulation of integrin function. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2003;2:703–716. doi: 10.1038/nrd1174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Legler DF, Wiedle G, Ross FP, Imhof BA. Superactivation of integrin αvβ3 by low antagonist concentrations. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:1545–1553. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.8.1545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Plant K, et al. Transient incorporation of native GluR2-lacking AMPA receptors during hippocampal long-term potentiation. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:602–604. doi: 10.1038/nn1678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hou Q, Zhang D, Jarzylo L, Huganir RL, Man HY. Homeostatic regulation of AMPA receptor expression at single hippocampal synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:775–780. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706447105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tallafuss A, Constable JR, Washbourne P. Organization of central synapses by adhesion molecules. Eur J Neurosci. 2010;32:198–206. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2010.07340.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McMahon SA, Díaz E. Mechanisms of excitatory synapse maturation by trans-synaptic organizing complexes. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 2011;21:221–227. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.12.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Abe K, Chisaka O, Van Roy F, Takeichi M. Stability of dendritic spines and synaptic contacts is controlled by αN-catenin. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:357–363. doi: 10.1038/nn1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jüngling K, et al. N-cadherin transsynaptically regulates short-term plasticity at glutamatergic synapses in embryonic stem cell-derived neurons. J Neurosci. 2006;26:6968–6978. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1013-06.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okuda T, Yu LM, Cingolani LA, Kemler R, Goda Y. β-Catenin regulates excitatory postsynaptic strength at hippocampal synapses. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:13479–13484. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0702334104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mendez P, De Roo M, Poglia L, Klauser P, Muller D. N-cadherin mediates plasticity-induced long-term spine stabilization. J Cell Biol. 2010;189:589–600. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201003007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bozdagi O, et al. Persistence of coordinated long-term potentiation and dendritic spine enlargement at mature hippocampal CA1 synapses requires N-cadherin. J Neurosci. 2010;30:9984–9989. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1223-10.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Nuriya M, Huganir RL. Regulation of AMPA receptor trafficking by N-cadherin. J Neurochem. 2006;97:652–661. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2006.03740.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Essmann CL, et al. Serine phosphorylation of ephrinB2 regulates trafficking of synaptic AMPA receptors. Nat Neurosci. 2008;11:1035–1043. doi: 10.1038/nn.2171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Heine M, et al. Activity-independent and subunit-specific recruitment of functional AMPA receptors at neurexin/neuroligin contacts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:20947–20952. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804007106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.de Wit J, et al. LRRTM2 interacts with Neurexin1 and regulates excitatory synapse formation. Neuron. 2009;64:799–806. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.12.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ballestrem C, Hinz B, Imhof BA, Wehrle-Haller B. Marching at the front and dragging behind: Differential αVβ3-integrin turnover regulates focal adhesion behavior. J Cell Biol. 2001;155:1319–1332. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200107107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cousins SL, Kenny AV, Stephenson FA. Delineation of additional PSD-95 binding domains within NMDA receptor NR2 subunits reveals differences between NR2A/PSD-95 and NR2B/PSD-95 association. Neuroscience. 2009;158:89–95. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2007.12.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Bolte S, Cordelières FP. A guided tour into subcellular colocalization analysis in light microscopy. J Microsc. 2006;224:213–232. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2818.2006.01706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.