Abstract

The epithelial-mesenchymal transition (EMT) plays an important role in breast cancer metastasis, especially in the most aggressive and lethal subtype, “triple-negative breast cancer” (TNBC). Here, we report that CD146 is a unique activator of EMTs and significantly correlates with TNBC. In epithelial breast cancer cells, overexpression of CD146 down-regulated epithelial markers and up-regulated mesenchymal markers, significantly promoted cell migration and invasion, and induced cancer stem cell-like properties. We further found that RhoA pathways positively regulated CD146-induced EMTs via the key EMT transcriptional factor Slug. An orthotopic breast tumor model demonstrated that CD146-overexpressing breast tumors showed a poorly differentiated phenotype and displayed increased tumor invasion and metastasis. We confirmed these findings by conducting an immunohistochemical analysis of 505 human primary breast tumor tissues and found that CD146 expression was significantly associated with high tumor stage, poor prognosis, and TNBC. CD146 was expressed at abnormally high levels (68.9%), and was strongly associated with E-cadherin down-regulation in TNBC samples. Taken together, these findings provide unique evidence that CD146 promotes breast cancer progression by induction of EMTs via the activation of RhoA and up-regulation of Slug. Thus, CD146 could be a therapeutic target for breast cancer, especially for TNBC.

Keywords: biomarker, F-actin

Breast cancer is the most common malignancy and the leading cause of cancer mortality in women worldwide (1). Death from breast cancer primarily results from cancer cells invading surrounding tissues and metastasizing to distal organs followed by formation of secondary tumors (1). The epithelial to mesenchymal transition (EMT), a developmental process in which epithelial cells lose polarity and develop a mesenchymal phenotype, has been implicated in the initiation of metastasis (2).

It is believed that EMTs endow cancer cells with migratory and invasive properties, and induce cancer stem cell (CSC) properties (2, 3). The primary events of an EMT are the loss of epithelial markers, followed by increased expression of mesenchymal markers, and rearrangement of the cytoskeleton. Previous reports reveal that EMTs can be regulated by several transcription factors, including SIP1, Snail, Slug, and Twist, which inhibit the epithelial phenotype and repress E-cadherin transcription (2, 4). A number of signal pathways converge on these transcription factors to induce an EMT, including the activation of small GTPases, especially RhoA, which regulates actin cytoskeleton reorganization (5). Increasing evidences show that in breast cancer, malignant cells undergo an EMT to become motile, especially in the most lethal and aggressive subtype, ER−/PR−/HER2− triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) (6).

CD146, also known as MCAM, M-CAM, and MUC18, was first identified as a melanoma-specific cell-adhesion molecule (7). Our previous findings have showed that CD146 is a marker for tumor angiogenesis (8), and that CD146 is important for endothelial cell migration and angiogenesis (9–11). We also found that CD146 promotes intermediate trophoblast invasion during pregnancy establishment (12, 13). In addition to this promigratory function of CD146 in the vascular system and normal development, CD146 has been implicated in tumor progression of several cancers, including melanoma (7), prostate cancer (14), epithelial ovarian cancer (15), and breast cancer (16), although the underlying mechanism is not very clear.

In this study, we set out to investigate the function of CD146 in breast cancer and its underlying mechanism. We first demonstrated that CD146 is a unique activator of EMTs in human breast cancer cells. We further explored the mechanism that mediates CD146-induced EMTs and assessed the function of CD146 in breast cancer progression in vivo using an orthotopic breast cancer model and human primary breast tumor tissues. These observations demonstrate that CD146 promotes breast cancer progression and may thus be a therapeutic target for breast cancer.

Results

CD146 Induces EMTs in Human Breast Cancer Cells.

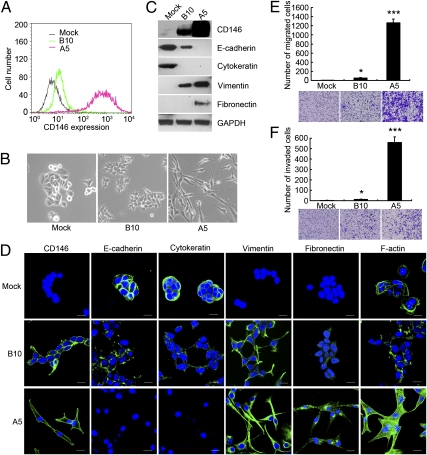

To investigate the role of CD146 in breast cancer progression, we overexpressed Flag-tagged CD146 in the human breast cancer cell line MCF-7, which does not express CD146 (16). We generated three stable cell clines from MCF-7, expressing CD146 at different levels. As shown by FACS analysis (Fig. 1A) and immunoblotting (Fig. 1C), the MCF-7-Mock clone (Mock), transfected with a blank vector, maintained a CD146− status, but CD146 clones MCF-7-B10 (B10) and MCF-7-A5 (A5) expressed CD146 at moderate and high levels, respectively.

Fig. 1.

CD146 induces EMTs in human breast cancer cells. (A) FACS analysis of CD146 expression in vector control MCF-7-Mock (Mock) and CD146 clones MCF-7-B10 (B10) and MCF-7-A5 (A5). (B) Morphology of Mock, B10, and A5 cells. Magnification, 200×. (C and D) Expression of CD146 and EMT markers analyzed by immunoblotting and immunofluorescence. Nuclei are shown with DAPI staining. (Scale bars, 20 μm.) (E and F) Migration and invasion assays of Mock, B10, and A5 cells. Data were collected from three wells, *P < 0.05, ***P < 0.001, compared with Mock cells. Representative images of migrated or invaded cells are also shown.

The characteristic morphological changes associated with EMTs were observed in CD146 clones (Fig. 1B). Mock cells maintained their cobblestone-like phenotype with strong cell-cell adhesion, whereas A5 cells, which had the highest CD146 expression, had an elongated fibroblast-like morphology, and pronounced cellular scattering. B10 cells, which had moderate CD146 expression, grew into cell clusters with looser cell-cell contacts, resembling a transition phenotype between Mock and A5 cells.

We next examined EMT markers in the three cells at both the protein and mRNA levels. As shown in Fig. 1C and Fig. S1, epithelial markers E-cadherin and cytokeratin were significantly decreased in B10 cells compared with Mock cells, and were not detected in A5 cells. In contrast, mesenchymal markers vimentin and fibronectin were gradually induced in B10 and A5 cells. These observations were also confirmed by immunofluoresence (Fig. 1D). In addition, compared with the peripheral F-actin staining in Mock and B10 cells, A5 cells showed significantly increased formation of central stress fibers by F-actin rearrangement, indicating that the intermediate filaments in A5 cells had reformed to a mesenchymal format.

The characteristic features of cells that have undergone an EMT are their dramatically increased migratory and invasive behaviors. As shown in Fig. 1 E and F, increased expression of CD146, especially in A5 cells, significantly induced a higher level of migration and invasion through Matrigel, whereas little migration or invasion was observed in Mock cells.

To verify whether these changes associated with EMTs were specifically induced by CD146, we down-regulated CD146 expression in A5 cells using siRNAs. As shown in Fig. S2A, CD146 expression in A5 cells transfected with siRNAs targeting CD146 was markedly decreased to one-quarter of that of the control transfected with siRNAs targeting GFP. We further observed that CD146 silencing decreased the level of mesenchymal markers vimentin and fibronectin and increased the level of the epithelial marker E-cadherin. Consistent with these changes in EMT markers, some A5 cells reverted to grow into tight cell clusters after CD146 silencing; cell migration and invasion were also significantly inhibited (Fig. S2 B–D). Taken together, changes in morphology, EMT marker, and cell migration and invasion after CD146 silencing demonstrate that CD146 underlies the EMTs in A5 cells.

To determine whether CD146-induced EMTs were cell type-specific or not, we expressed CD146 in the CD146− Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells, a cell model for EMT study. Similar to the results obtained in MCF-7 cells, changes in morphology, EMT markers, and cell migration and invasion were observed in CD146 clone MDCK-B7 cells (Fig. S3), strongly demonstrating that CD146 is a unique EMT inducer.

CD146-Induced EMTs Generate Breast CSC-Like Cells.

It is reported that mammary epithelial cells that have undergone EMTs increase the CD44high/CD24low population and the capabilities of mammosphere formation, which are characteristic features of normal mammary stem cells and breast CSCs (3). To determine whether CD146-induced EMTs generate CSC-like cells, we performed FACS to analyze the CD44high/CD24low population in MCF-7 clones. As shown in Fig. 2A, almost all of the A5 cells acquired a CD44high/CD24low expression phenotype with higher CD44 expression, but most of the B10 cells acquired this phenotype with lower CD44 expression; this shift was not observed in Mock cells, which mainly maintained the CD44high/CD24high phenotype. These results imply that CD146 expression leads to gradual down-regulation of CD24, whereas its impact on CD44 expression seems more complex. Mammosphere formation assay showed an increase in both the size and number of mammospheres in A5 (P < 0.05) and B10 cells compared with Mock cells (Fig. 2 B and C). These observations indicate that CD146 triggers the expression of cell-surface markers and functional characteristics associated with CSCs, an important feature recently defined for inducers of EMTs.

Fig. 2.

CD146-induced EMTs generate breast CSC-like cells. (A) FACS analysis of cell-surface markers CD44 and CD24 in Mock, B10, and A5 cells. (B and C) Morphology and quantification of mammospheres formed by Mock, B10, and A5 cells. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) *P < 0.05, compared with Mock cells.

RhoA Activation and Slug Up-Regulation Mediate CD146-Induced EMTs.

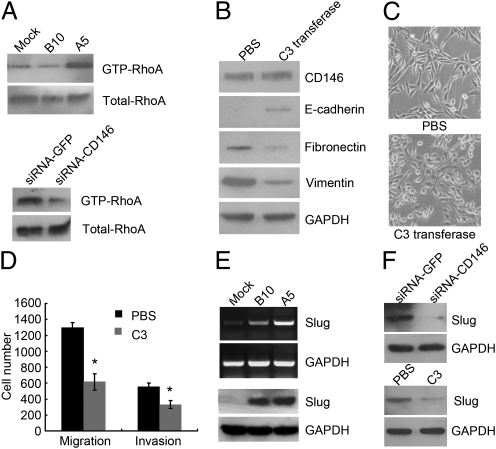

Because we observed significant alterations of F-actin cytoskeleton in A5 cells, we further examined the activity of Rho GTPases, including RhoA, Rac1, and Cdc42, in our cell lines. These GTPases have been found to play important roles in mediating cytoskeleton rearrangements (17). We found that the active form of RhoA (GTP-RhoA) was dramatically increased in A5 cells compared with Mock and B10 cells (Fig. 3A, Upper), whereas the active forms of Rac1 (GTP-Rac1) and Cdc42 (GTP-Cdc42) were unchanged (Fig. S4A). CD146 silencing efficiently decreased the level of GTP-RhoA in A5 cells (Fig. 3A, Lower), suggesting that RhoA acts downstream of signal pathways induced by CD146 overexpression in A5 cells.

Fig. 3.

RhoA activation and Slug up-regulation mediate CD146-induced EMTs. (A) GTP-RhoA affinity pull-down assay to determine the level of GTP-RhoA in Mock, B10, and A5 (Upper), and the level of GTP-RhoA after CD146 silencing in A5 cells (Lower). (B) Immunoblotting of CD146 and EMT markers in A5 cells after PBS or C3 transferase treatment (1 μg/mL, 24 h). (C) Morphology of A5 cells after PBS or C3 transferase treatment. Magnification, 100×. (D) Migration and invasion assays in A5 cells after PBS or C3 transferase treatment. *P < 0.05, compared with the control. (E) Slug expression in Mock, B10, and A5 cells analyzed by RT-PCR (Upper) and immunoblotting (Lower). (F) Slug expression in A5 cells after CD146 silencing (Upper) or C3 transferase treatment (Lower) analyzed by immunoblotting.

To further determine whether RhoA directly mediates CD146-induced EMTs, we used exoenzyme C3 transferase, a specific inhibitor of Rho, to inhibit RhoA activity in A5 cells. We observed that inhibition of RhoA activity in A5 cells increased expression of E-cadherin and decreased expression of vimentin and fibronectin, although it had no effect on CD146 expression (Fig. 3B). Consistent with the changes in EMT markers, A5 cells became less fibroblastic and less dispersed, their migratory and invasive behaviors were also significantly inhibited (Fig. 3 C and D), suggesting that RhoA activation is responsible for CD146-induced EMTs.

Loss of E-cadherin expression is the key event leading to the disruption of tight cell-cell contacts and the triggering of EMTs (18). A number of signal pathways associated with EMTs converge on transcription factors SIP1, Snail, Slug, and Twist to inhibit E-cadherin transcription. Because E-cadherin transcripts were decreased in B10 and A5 cells (Fig. S1), we wondered which transcription factors contributed to these changes. RT-PCR and immunoblotting (Fig. 3E) showed that Slug was gradually increased in Mock, B10, and A5 cells, and expressed at the highest level in A5 cells that showed the highest CD146 expression and the lowest E-cadherin expression. However, SIP1 was unchanged, Snail was undetected in A5 cells, and Twist was slightly increased compared with Mock cells, whose expressions were all not correlated with CD146 expression in the three cells (Fig. S4B). More importantly, CD146 silencing or RhoA inhibition by exoenzyme C3 transferase in A5 cells significantly decreased the level of Slug (Fig. 3F), suggesting that Slug is downstream of RhoA in CD146-induced EMTs and is positively regulated by CD146 expression and RhoA activation.

Taken together, these results demonstrate that CD146 overexpression contributes to the activation of RhoA, which induces F-actin cytoskeleton rearrangements and Slug expression. Slug subsequently inhibits E-cadherin transcription, resulting in decreased expression of E-cadherin and disruption of tight cell-cell contacts, and eventually leads to EMTs in MCF-7 cells.

Down-Regulation of CD146 in Mesenchymal Breast Cancer Cells Suppresses the Mesenchymal Phenotype.

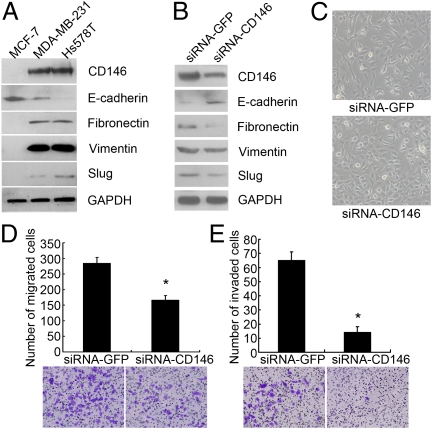

Having shown that CD146 is an EMT inducer in epithelial breast cancer cells, we further investigated the function of CD146 in two invasive mesenchymal breast cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-231 and Hs578T (19). As anticipated, CD146 expression was much higher in these two cells than in MCF-7 cells (Fig. 4A). They also expressed mesenchymal markers vimentin, fibronectin, and Slug, but the epithelial marker E-cadherin was lower or could not be detected.

Fig. 4.

Down-regulation of CD146 expression reverses the mesenchymal phenotype of MDA-MB-231 cells. (A) Immunoblotting of CD146 and EMT markers in MCF-7, Hs578T, and MDA-MB-231 cells. (B) Immunoblotting of CD146, E-cadherin, fibronectin, vimentin, and Slug after CD146 silencing in MDA-MB-231 cells. (C) Morphology of MDA-MB-231 cells after CD146 silencing. Magnification, 100×. (D and E) Migration and invasion assays of MDA-MB-231 cells after CD146 silencing. Data were collected from three wells, *P < 0.05, compared with the control. Representative images of migrated or invaded cells are also shown.

We next down-regulated CD146 expression in MDA-MB-231 cells with siRNAs targeting CD146; siRNAs targeting GFP were used as control. As shown in Fig. 4B, CD146 expression dramatically decreased to about 50% of that of the control. Consequently, the epithelial marker E-cadherin was up-regulated, the mesenchymal markers vimentin, fibronectin, and Slug were down-regulated. We observed that MDA-MB-231 cells with reduced CD146 expression partly lost their fibroblastic phenotype and grew into tight cell clusters, their migratory and invasive behaviors were also significantly inhibited (Fig. 4 C–F). Similar results were also obtained in Hs578T cells transfected with siRNAs targeting CD146 (Fig. S5), suggesting that CD146 contributes to the invasive behaviors of the mesenchymal breast cancer cells.

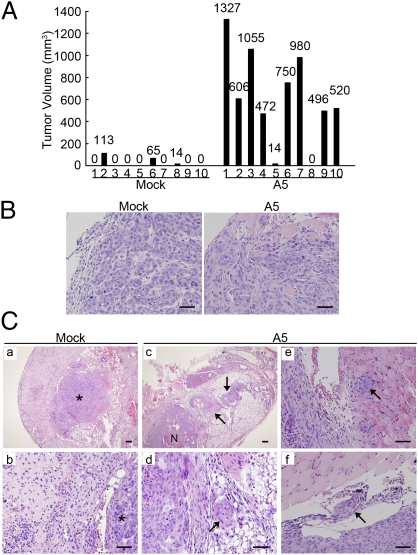

CD146 Promotes Tumor Invasion in Vivo.

We then addressed the key question that whether CD146-induced EMTs increase tumor invasion in vivo. We implanted Mock and A5 cells into the mammary fat pads of SCID/Beige mice and terminated the experiment at week 10 postimplantation. As shown in Fig. 5A, 80% of the mice implanted with A5 cells developed tumors, compared with only 30% of the mice implanted with Mock cells. Moreover, the average volume of A5 tumors was much higher than that of Mock tumors, suggesting that CD146 significantly promotes breast tumorigenesis and growth in the orthotopic breast cancer model.

Fig. 5.

CD146 promotes tumor invasion in vivo. (A) Individual volume of Mock and A5 tumors at week 10 after orthotopic injection. (B) Mock and A5 tumor sections stained with H&E. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) (C) H&E staining in Mock and A5 tumor sections and adjacent tissues. (a and b) Mock tumors without stromal invasion. (c and d, arrows) Areas of stromal invasion of A5 tumors. (e and f, arrows) Areas of muscular and vascular invasion of A5 tumors. Asterisks, Tumor mass. N, necrosis. (Scale bars, 100 μm.)

We first confirmed that A5 and Mock tumors continued to maintain their mesenchymal or epithelial phenotypes in vivo. As shown in Fig. S6A, A5 tumors maintained a high level of Flag-tagged CD146 expression even at week 10 postimplantation, whereas Mock tumors showed no CD146 expression. A5 tumors were positive for vimentin, but Mock tumors were positive for E-cadherin. Furthermore, there were significant differences between Mock and A5 tumors in cytology and growth pattern (Fig. 5B). The cells of Mock tumors were normal in appearance and developed into focal tubules, showing a well-differentiated pattern. However, A5 tumors were composed of irregular cells with larger, more prominent nucleoli, indicating a poorly differentiated phenotype that corresponds to a higher histological grade and poorer prognosis in human breast cancer.

Next we examined Mock and A5 tumors and corresponding neighboring tissues to evaluate tumor invasion. As anticipated, Mock tumors were tightly surrounded by fibrotic capsules, indicating their noninvasive phenotype (Fig. 5C, a and b). In contrast, A5 tumors showed apparent local invasion, with small aggregates of tumor cells invading into the adjacent stroma (Fig. 5C, c and d), muscle (Fig. 5C, e), skin, fat tissue, and ribs (Fig. S6B). We observed that A5 cells apparently invaded into blood vessels on the edge of the tumor mass (Fig. 5C, f), indicating possible metastasis. Taken together, our results show that overexpression of CD146 confers an invasive phenotype on noninvasive MCF-7 cells.

To determine whether CD146-induced EMTs would affect tumor angiogenesis, we performed immunofluorescence staining with CD31 for endothelial cells and Flag for tumor cells. We found that the invasion fronts of A5 tumors exhibited a much higher level of angiogenesis in contrast with Mock tumors, although there was no significant difference in vessel density in the center of these tumors (Fig. S6 C–E). We observed that new vessels were accompanied by islands of A5 tumor cells that had invaded into the stroma, indicating that CD146-expressing tumors induce further angiogenesis, facilitating tumor invasion and metastasis.

CD146 Initiates Tumor Metastasis in Vivo.

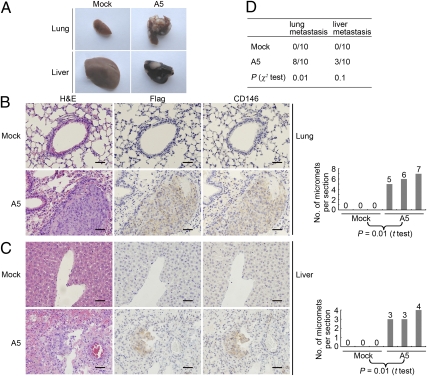

We next questioned whether CD146 could initiate tumor metastasis in vivo. Organs of mice carrying Mock and A5 tumors were dissected out 10 wk after implantation and fixed for further analysis. As shown in Fig. 6A, lungs and livers from mice carrying A5 tumors displayed large numbers of visible breast tumor metastases, compared with normal lungs and livers from mice carrying Mock tumors, indicating relatively late dissemination of A5 cells from the primary tumors.

Fig. 6.

CD146 promotes breast tumor metastasis in vivo. (A) Morphology of lung and liver metastases formed by Mock and A5 cells at week 10 after orthotopic injection. (B and C) H&E-, Flag-, and CD146-stained section of lungs and livers isolated from mice carrying Mock and A5 tumors. Arrows indicate representative micrometastases (Left). Numbers of micrometastases (micromets) per section in lung and livers in individual mice carrying Mock and A5 tumors (Right). Data were collected from three mice per group. t Tests were used to determine differences. P < 0.05 was considered to be significant. (Scale bars, 100 μm.) (D) Incidence of lung and liver metastasis in mice carrying Mock and A5 tumors, as analyzed by morphology observation and immunohistochemistry. The Pearson χ2 test was used to determine correlations. P < 0.05 were considered significant.

Metastases in the lungs and livers of mice carrying tumors were confirmed by H&E and immunohistochemical staining for Flag and CD146 (Fig. 6 B and C). On average, we found six micrometastases per 5-μm section in lungs, and four micrometastases in livers from mice carrying A5 tumors, in stark contrast to no micrometastases in the lungs and livers from mice carrying Mock tumors.

In summary, 80% of mice that carrying A5 tumors exhibited numerous lung metastases and 30% of these mice displayed apparent liver metastasis, whereas no lung and liver metastases were found in the mice carrying Mock tumors (Fig. 6D).These observations demonstrate that CD146 strongly promotes breast cancer metastasis in vivo.

CD146 Is Significantly Associated with TNBC.

A critical question raised from our in vitro and in vivo data was whether CD146 expression clinically correlated with human breast cancer progression. To address this issue, we performed immunohistochemistry to detect CD146 expression in 505 human primary breast cancers. Although only 35% of tumors were positive for CD146 staining, CD146 expression was significantly associated with advanced tumor grade, with a positive status for Ki-67, and with poor prognosis in breast cancer (Tables S1 and S2). Furthermore, there was significant correlation between CD146+ tumors and a shorter progression-free survival or overall survival (Fig. S7). These observations demonstrate that CD146 expression significantly correlates with invasive breast cancer.

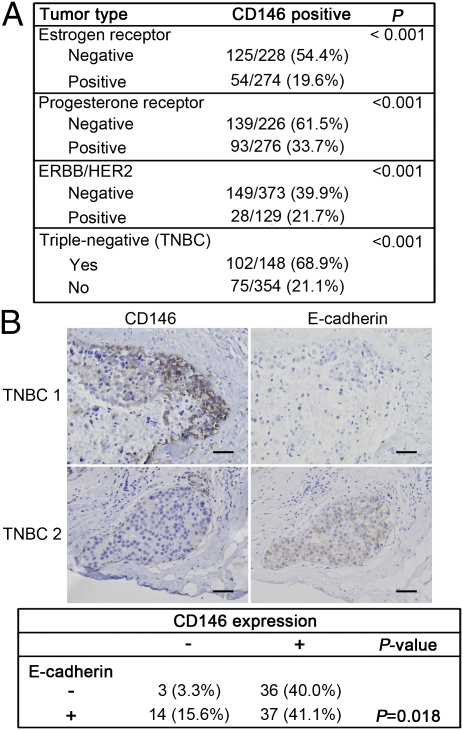

Interestingly, we observed abnormally high expression of CD146 in TNBC, the most aggressive breast cancer with EMT-like features. As shown in Fig. 7A, there was a striking correlation between CD146 expression and the triple-negative phenotype (P < 0.001). Of TNBC samples, 68.9% were CD146+, in contrast to 21.2% in non-TNBC samples. CD146 expression was also significantly correlated with ER-, PR-, and HER2-negative status (P < 0.001), respectively.

Fig. 7.

CD146 is associated with triple-negative breast cancer. (A) Associations of CD146 expression with ER-, PR-, HER2-statuses, and with the triple-negative phenotype in 502 human breast tumor tissues, for which ER, PR, and HER2 status were available. (B) Representative immunohistochemical staining of CD146 and E-cadherin in 2 TNBC samples (Upper), and statistical correlations between CD146 expression and E-cadherin in TNBC (Lower). Only membrane expression of E-cadherin was considered to be positive. The Pearson χ2 test was used to determine correlations. P < 0.05 were considered significant. (Scale bars, 100 μm.)

To investigate whether the abnormally high expression of CD146 in TNBC accounts for its EMT-like features, we further analyzed correlations between CD146 and E-cadherin expression in 90 TNBC samples. As shown in Fig. 7B, CD146 was frequently expressed at the leading edge of invasion. CD146+ TNBC samples tended to be either E-cadherin–negative or to express E-cadherin in the cytoplasm. In contrast, CD146− TNBC samples expressed E-cadherin in membranes, the normal expression pattern for E-cadherin. CD146 expression was significantly associated with a reduction of E-cadherin in TNBC samples (P = 0.01). These clinical data are consistent with our observations in cell cultures and the orthotopic breast cancer mouse model, demonstrating the pathological relevance of CD146 in the regulation of EMTs.

Discussion

In this study, we are unique in demonstrating that CD146 is a regulator of the EMTs in breast cancer progression. We confirm this finding by providing the following evidence. First, CD146 overexpression in noninvasive epithelial breast cancer cells represses the epithelial phenotype, induces a mesenchymal phenotype, and dramatically increases migratory and invasive behaviors and CSC-like properties. Second, CD146 down-regulation in invasive mesenchymal breast cancer cells reverses their malignant phenotypes. Third, CD146 induces tumorigenesis and a poorly differentiated phenotype, and promotes tumor invasion and metastasis in an orthotropic breast cancer mouse model. Finally, by examining 505 human primary breast cancer tissues, we found that CD146 expression is significantly associated with high tumor stage, poor prognosis, and TNBC, providing pathological support for our in vitro and animal studies. Our studies are consistent with a recent report describing a significant correlation between CD146 expression and invasive breast cancer (16), and have assessed the mechanism underlying this correlation.

Another important objective of this study was to clarify the molecular mechanism underlying CD146-induced EMTs. First, we found that the small GTPase RhoA is activated in CD146-overexpressing cells, and we further demonstrated that activation of RhoA is responsible for CD146-induced EMTs rather than being a consequence of them. Previous reports have shown that RhoA activation results in disruptions of cell-cell adhesion and EMTs in TGF-β1–stimulated mammary epithelial cells (20), colon carcinoma cells (21), and podoplanin-overexpressing MDCK cells (22). Second, we observed that CD146-induced EMTs increase Slug expression, whereas other transcriptional factors SIP1, Snail, and Twist were not correlated with CD146 expression. Slug is a member of the Snail family, and it is both necessary and sufficient to repress E-cadherin transcription and trigger the EMT process in breast cancer (23). We demonstrate that both CD146 silencing and RhoA inhibition in CD146-overexpressing cells significantly decreased Slug expression. A previous report shows that Slug down-regulation is sufficient to restore E-cadherin expression in breast epithelial cells (24). Third, the fact that CD146 is able to activate RhoA without affecting Rac1 and Cdc42 activity suggests a direct link between CD146 and RhoA. Our data show that CD146 physically interacts with ERM proteins and then recruits RhoGDI1 via the phosphorylated ERM proteins, and finally induces RhoA activation in melanoma cells (25), providing evidence for this function of CD146 in breast cancer cells. However, unraveling the detailed signaling pathways involved in RhoA and the CD146-induced EMTs will require further research.

Our studies on the role of CD146 in breast cancer progression have promising clinical implications. Foremost, our findings indicate that CD146 could be a unique therapeutic target, with particular relevance to clinically aggressive TNBC. TNBC is the most lethal subtype for its high incidence of metastasis and resistance to current targeted therapies (26). As EMTs account for the aggressiveness and stemness of TNBC, targeting the EMT-like phenotype becomes a unique strategy for TNBC treatment. Our results have shown that CD146 is expressed at abnormally high levels and is associated with a reduction of E-cadherin in TNBC. CD146 silencing in the so-called “TNBC cell line” MDA-MB-231 partly reverses its mesenchymal phenotype, implying that CD146-induced EMTs partially explain the mesenchymal and malignant characteristics of TNBC. In addition, increasing evidences support the critical role played by tumor angiogenesis in breast cancer progression (26). Because CD146 has also been proposed as a marker for tumor angiogenesis (8), targeting CD146 would have a double role, targeting the mesenchymal phenotype and tumor angiogenesis at the same time, thus will be a promising strategy in TNBC treatment.

Although previous reports have shown that CD146 significantly correlates with advanced tumor stage in malignant melanoma (13), prostate cancer (14), epithelial ovarian cancer (15), and mesothelioma (27, 28), little is known about the underlying mechanisms. Here, we report a unique role for CD146; the induction of EMTs to promote breast cancer progression. As the EMT is regarded as a mechanism that is conserved in developmental processes and the progression of pathological diseases (2), we wonder whether CD146-induced EMTs might play a role in tumor progression in other CD146-positive cancers. A previous report showed a negative correlation between CD146 and E-cadherin expression in prostate cancer cell lines (29), implying that CD146-induced EMTs are not limited to breast cancer and might have a role in various types of cancers. More studies are needed to confirm the implication.

In conclusion, we demonstrate that CD146 plays a critical role in promoting breast cancer progression by up-regulating active RhoA and Slug to promote EMTs. Furthermore, the striking correlation between abnormally high CD146 expression and TNBC at least partially explains its role as an EMT inducer in the most aggressive breast cancer. Thus, CD146 can be used as a potential therapeutic target for breast cancer, especially for TNBC.

Materials and Methods

Reagents, cell lines, and transfections are listed in SI Materials and Methods. In vitro migration and invasion assays, immunofluoresence, mammosphere assay, and RohA activity assay were conducted using standard procedures detailed in SI Materials and Methods. Construction of orthotopic breast cancer animal models and collection of clinical samples followed established procedures described in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by grants from 973 Program (2009CB521704, 2011CB933503, 2012CB934003, and 2011CB915502), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (91029732 and 30930038), and the Knowledge Innovation Program of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KSCX2-YW-M15).

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1111053108/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics. CA Cancer J Clin. 2011;61:69–90. doi: 10.3322/caac.20107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thiery JP, Acloque H, Huang RY, Nieto MA. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions in development and disease. Cell. 2009;139:871–890. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mani SA, et al. The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell. 2008;133:704–715. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang Y, Massagué J. Epithelial-mesenchymal transitions: Twist in development and metastasis. Cell. 2004;118:277–279. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yilmaz M, Christofori G. EMT, the cytoskeleton, and cancer cell invasion. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2009;28:15–33. doi: 10.1007/s10555-008-9169-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mostert B, Sleijfer S, Foekens JA, Gratama JW. Circulating tumor cells (CTCs): Detection methods and their clinical relevance in breast cancer. Cancer Treat Rev. 2009;35:463–474. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2009.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lehmann JM, Riethmüller G, Johnson JP. MUC18, a marker of tumor progression in human melanoma, shows sequence similarity to the neural cell adhesion molecules of the immunoglobulin superfamily. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1989;86:9891–9895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.86.24.9891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yan X, et al. A novel anti-CD146 monoclonal antibody, AA98, inhibits angiogenesis and tumor growth. Blood. 2003;102:184–191. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-04-1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bu P, et al. Anti-CD146 monoclonal antibody AA98 inhibits angiogenesis via suppression of nuclear factor-kappaB activation. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:2872–2878. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-06-0260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kang Y, et al. Knockdown of CD146 reduces the migration and proliferation of human endothelial cells. Cell Res. 2006;16:313–318. doi: 10.1038/sj.cr.7310039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng C, et al. Endothelial CD146 is required for in vitro tumor-induced angiogenesis: The role of a disulfide bond in signaling and dimerization. Int J Biochem Cell Biol. 2009;41:2163–2172. doi: 10.1016/j.biocel.2009.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liu Q, et al. Pre-eclampsia is associated with the failure of melanoma cell adhesion molecule (MCAM/CD146) expression by intermediate trophoblast. Lab Invest. 2004;84:221–228. doi: 10.1038/labinvest.3700033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu Q, et al. Blockade of adhesion molecule CD146 causes pregnancy failure in mice. J Cell Physiol. 2008;215:621–626. doi: 10.1002/jcp.21341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wu GJ, et al. Isolation and characterization of the major form of human MUC18 cDNA gene and correlation of MUC18 over-expression in prostate cancer cell lines and tissues with malignant progression. Gene. 2001;279:17–31. doi: 10.1016/s0378-1119(01)00736-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aldovini D, et al. M-CAM expression as marker of poor prognosis in epithelial ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1920–1926. doi: 10.1002/ijc.22082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zabouo G, et al. CD146 expression is associated with a poor prognosis in human breast tumors and with enhanced motility in breast cancer cell lines. Breast Cancer Res. 2009;11:R1. doi: 10.1186/bcr2215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ridley AJ. Rho GTPases and cell migration. J Cell Sci. 2001;114:2713–2722. doi: 10.1242/jcs.114.15.2713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Perl AK, Wilgenbus P, Dahl U, Semb H, Christofori G. A causal role for E-cadherin in the transition from adenoma to carcinoma. Nature. 1998;392:190–193. doi: 10.1038/32433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Finn RS, et al. Dasatinib, an orally active small molecule inhibitor of both the src and abl kinases, selectively inhibits growth of basal-type/”triple-negative” breast cancer cell lines growing in vitro. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2007;105:319–326. doi: 10.1007/s10549-006-9463-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhowmick NA, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 mediates epithelial to mesenchymal transdifferentiation through a RhoA-dependent mechanism. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:27–36. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.1.27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gulhati P, et al. mTORC1 and mTORC2 regulate EMT, motility, and metastasis of colorectal cancer via RhoA and Rac1 signaling pathways. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3246–3256. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Martín-Villar E, et al. Podoplanin binds ERM proteins to activate RhoA and promote epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:4541–4553. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Alves CC, Carneiro F, Hoefler H, Becker KF. Role of the epithelial-mesenchymal transition regulator Slug in primary human cancers. Front Biosci. 2009;14:3035–3050. doi: 10.2741/3433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Leong KG, et al. Jagged1-mediated Notch activation induces epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition through Slug-induced repression of E-cadherin. J Exp Med. 2007;204:2935–2948. doi: 10.1084/jem.20071082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo Y, et al. Recognition of CD146 as an ERM-binding protein offers novel mechanisms for melanoma cell migration. Oncogene. 2011 doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.244. 10.1038/onc.2011.244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Anders CK, Carey LA. Biology, metastatic patterns, and treatment of patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Clin Breast Cancer. 2009;9(Suppl 2):S73–S81. doi: 10.3816/CBC.2009.s.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bidlingmaier S, et al. Identification of MCAM/CD146 as the target antigen of a human monoclonal antibody that recognizes both epithelioid and sarcomatoid types of mesothelioma. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1570–1577. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-1363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sato A, et al. Immunocytochemistry of CD146 is useful to discriminate between malignant pleural mesothelioma and reactive mesothelium. Mod Pathol. 2010;23:1458–1466. doi: 10.1038/modpathol.2010.134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu GJ, et al. Expression of a human cell adhesion molecule, MUC18, in prostate cancer cell lines and tissues. Prostate. 2001;48:305–315. doi: 10.1002/pros.1111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.