SUMMARY

Objective

To summarize literature on the concurrent and predictive validity of MRI-based measures of osteoarthritis (OA) structural change.

Methods

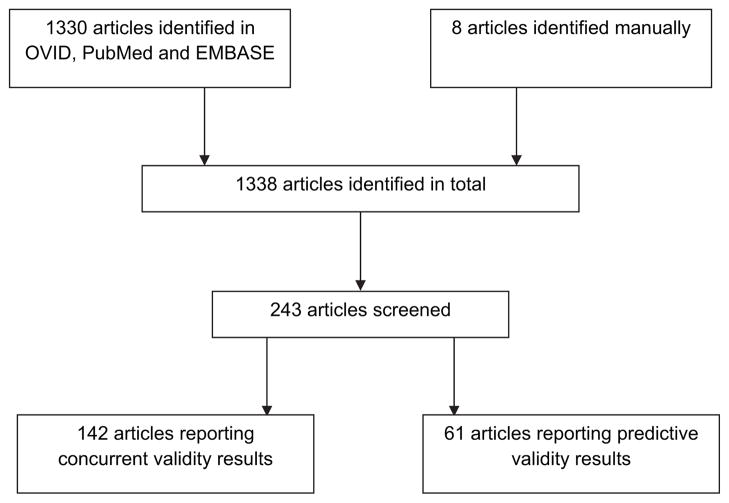

An online literature search was conducted of the OVID, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsychInfo and Cochrane databases of articles published up to the time of the search, April 2009. 1338 abstracts obtained with this search were preliminarily screened for relevance by two reviewers. Of these, 243 were selected for data extraction for this analysis on validity as well as separate reviews on discriminate validity and diagnostic performance. Of these 142 manuscripts included data pertinent to concurrent validity and 61 manuscripts for the predictive validity review. For this analysis we extracted data on criterion (concurrent and predictive) validity from both longitudinal and cross-sectional studies for all synovial joint tissues as it relates to MRI measurement in OA.

Results

Concurrent validity of MRI in OA has been examined compared to symptoms, radiography, histology/pathology, arthroscopy, CT, and alignment. The relation of bone marrow lesions, synovitis and effusion to pain was moderate to strong. There was a weak or no relation of cartilage morphology or meniscal tears to pain. The relation of cartilage morphology to radiographic OA and radiographic joint space was inconsistent. There was a higher frequency of meniscal tears, synovitis and other features in persons with radiographic OA. The relation of cartilage to other constructs including histology and arthroscopy was stronger. Predictive validity of MRI in OA has been examined for ability to predict total knee replacement (TKR), change in symptoms, radiographic progression as well as MRI progression. Quantitative cartilage volume change and presence of cartilage defects or bone marrow lesions are potential predictors of TKR.

Conclusion

MRI has inherent strengths and unique advantages in its ability to visualize multiple individual tissue pathologies relating to pain and also predict clinical outcome. The complex disease of OA which involves an array of tissue abnormalities is best imaged using this imaging tool.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Magnetic resonance imaging, Validity

Introduction

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) is being developed as a method to assess joint morphology in osteoarthritis (OA), with the goal of providing a sensitive non-invasive tool for the study of healthy and diseased states, and a means of assessing the effectiveness of interventions for osteoarthritis. Traditionally structural assessment of OA has relied upon the plain radiograph which has capacity to image the joint space and osteophytes1. MRI has many advantages in visualizing the joint, and recent efforts are yielding a variety of approaches that offer the potential for monitoring this prevalent synovial joint disease2. Because OA is a disease of the whole synovial joint, not just the cartilage, measurements of structure need to be seen broadly and capture important anatomic features, including osteophytes, effusions, meniscal tears, subchondral bone architectural changes or ligamentous instability, in addition to cartilage loss2. There is an abundant literature describing the concurrent validity of MRI as it relates to comparable constructs such as histology and radiography but little if any effort has been made to systematically summarize this literature.

Similarly the merits of any OA structural assessment will undoubtedly be assessed for their clinical relevance. There are multiple determinants of pain and functional limitation in OA and there may be many more unknown3. Many studies have examined whether the loss of structural integrity is in some way the physical correlate of these symptoms. Traditionally most epidemiologic studies have relied upon plain radiography to define disease. The major limitation of this method is that measures of symptoms correlate poorly with x-ray features. Less than 50% of people with evidence of OA on plain radiographs have symptoms related to these findings4. Uncertainty as to whether measurements of MRI structure alone will adequately reflect what structure connotes, or whether other metrics of structure should also be considered, need to be systematically evaluated. The relationships between structure and pain and/or function and between structure and future outcomes (e.g., arthroplasty) are critical in determining the clinical relevance of MRI.

In psychometrics, validity refers to the degree to which a study accurately reflects or assesses the specific concept that the researcher is attempting to measure. There are many types of validity of which one, criterion validity, is used to demonstrate the accuracy of a measure or procedure by comparing it with another measure or procedure which has been demonstrated to be valid. There is a contention in the OA field about the validity of a number of biomarkers and clinical endpoints and their inclusion here is in an effort to be comprehensive and does not diminish the credible concerns about the lack of well validated clinical endpoints5. If the test data and criterion data are collected at the same time, this is referred to as concurrent validity evidence. If the test data is collected first in order to predict criterion data collected at a later point in time, then this is referred to as predictive validity evidence. The purpose of this systematic review was to summarize the OA MRI literature with regards to both concurrent and predictive validity.

Material and methods

Systematic literature search details

An online literature search was conducted using the OVID MEDLINE (1945–), EMBASE (1980–) and Cochrane databases (1998–) to identify the articles published up to April 2009, with the search entries “MRI”, and “osteoarthritis”, “osteoarthritides”, “osteoarthrosis”, “osteoarthroses”, “degenerative arthritis”, “degenerative arthritides”, or “osteoarthritis deformans”. The abstracts of the 1330 citations received with this search were then preliminarily screened for relevance by two reviewers (KH and DJH). For this preliminary search, all articles which used MRI, in some form, on patients with osteoarthritis of the knee, hip, or hand were included. Although review articles were not included (see Inclusion/exclusion criteria), citations found in any review articles which were not already included in our preliminary search were screened for possible inclusion in this study. This added 7 more relevant studies to our search. One further article was added, before publication, by one of authors of this meta-analysis bringing the preliminary total to 1338.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

Only studies published in English were included. Studies presenting non-original data were excluded, such as reviews, editorials, opinion papers, or letters to the editor. Studies with questionable clinical relevance and those using non-human subjects or specimens were excluded. Studies in which rheumatoid, inflammatory, or other forms of arthritis were included in the OA datasets were excluded, as well as general joint-pertinent MRI studies not focused on OA. Studies with no extractable, numerical data were excluded. Only those articles which had some measure of diagnostic performance were included. Any duplicates which came up in the preliminary search were excluded. Of the preliminary 1338 abstracts, 243 were selected for data extraction (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of the screening process for articles included in the systematic review.

Data abstraction

Two reviewers (KH and LM) independently abstracted the following data: (1) patient demographics; (2) MRI make, sequences and techniques used, tissue types viewed; (3) study type and funding source; (4) details on rigor of study design to construct the Downs methodological quality score6; (5) MRI reliability/reproducibility data; (6) MRI diagnostic measures and performance; (7) gold standard measures against which the MRI measure was evaluated; (8) treatment and MRI measures (when appropriate).

The Downs methodological quality score6 collects a profile of scores for both randomized trials and observational studies in terms of quality of reporting, internal validity (bias and confounding), power, external validity so that the overall study quality score reflects all of these elements. Answers were scored 0 (No) or 1 (Yes), except for one item in the Reporting subscale, which scored 0–2 and the single item on power, which was scored 0–5. The possible range is from 0 to 27 where 0 represents poor quality and 27 optimal quality.

We used a data abstraction tool constructed in EpiData (Entry version 2.0 Odense, Denmark) and more than one reviewer undertook the data abstraction. The data collection forms were designed to target the objectives of the review, and were piloted prior to conducting the study.

The outcomes for psychometric properties on MRI were examined using the OMERACT filter7,8. The specific focus of this review is upon the truth domain: is the measure truthful, does it measure what it intends to measure? More specifically we were interested in criterion validity; for both the concurrent [Does it agree (by independent and blind comparison) with a measure that reflects the same concept] and predictive [Does it predict (by independent and blind comparison) a future ‘gold standard’] validity of MRI in OA. If the test data and criterion data are collected at the same time, this is referred to as concurrent validity evidence. If the test data is collected first in order to predict criterion data collected at a later point in time, then this is referred to as predictive validity evidence.

It is critical to delineate what we mean by the various terms used, as current usage is often incorrect, and this ambiguity may stem from an incorrect understanding of appropriate definitions. Whilst there are several definitions that have been proposed9–13, the brief synthesis of some working definitions is as follows:

biological marker (biomarker)— a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biological processes, pathogenic processes or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic agent.

clinical endpoint—a clinically meaningful measure of how a patient feels, functions, or survives.

For the purposes of this analysis, MRI (the biomarker) is directly compared both to clinical endpoints (symptoms, total knee replacement (TKR)) as well as other biomarkers (including radiography, CT, histology, arthroscopy, alignment). The presentation of the data in the results reflects presentation of clinical endpoints before comparison with other biomarkers.

There is some overlap in the manuscripts for which data is extracted for these two types of validity. The large majority of studies for concurrent validity were cross-sectional studies although some longitudinal studies reported cross-sectional results and thus are included in the concurrent validity data. There is no attempt made to create summary estimates as the validity effect measures [i.e., odds ratio (OR), Beta coefficient, r, P-value of difference] used in this literature are very heterogeneous.

Results

Concurrent validity (Table I)

Table I.

Summary table of studies reporting data on concurrent validity of MRI in OA

| Reference: Author, Journal, Year, PMID |

Whole sample size |

No. of cases |

No. of controls |

Age, yrs, mean(SD), range | No. (%) of females | Quantitative cartilage |

Compositional techniques |

Semi-quantitative | Cartilage | Synovium | Bone | Bone marrow lesions |

Meniscus | Ligament | Study design |

Score of methodological quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chan WP; American Journal of Roentgenology; 1991; 189204036 |

20 | 20 | 0 | 58(Range: 42–73) | 11 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Cross-sectional | 6 |

| McAlindon TE; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 1991; 199486190 |

12 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Case control | 3 | ||||

| Li KC; Magnetic Resonance Imaging; 1988; 339872891 |

10 | 10 | 0 | (Range: 33–78) | 9(90%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

4 |

| Fernandez-Madrid F; Magnetic Resonance Imaging; 1994; 793465692 |

92 | 52 | 40 | Controls: 49(15), (Rang: 22–78); OA patients: 55(14), (Range: 25–86) |

60 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 11 |

| Karvonen RL; Journal of Rheumatology; 1994; 796607527 |

92 | 52 | 40 | Reference: 49(15), (Range: 22–78); All OA patients: 55(14), (Range: 25 –86); Bilateral OA: 53(13), (Range: 25–73) |

60 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Case control | 11 |

| Peterfy CG; Radiology; 1994; 802942093 | 8 | 5 | 3 | 62(Range: 45–82) | 4(50%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 4 |

| Blackburn WD Jr; Journal of Rheumatology; 1994; 803539237 | 33 | 33 | 0 | 62.7(9.1), (Range: 44–79) | 17 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 6 |

| Broderick LS; American Journal of Roentgenology; 1994; 827370061 | 23 | 13 | 10 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 4 | ||

| Miller TT; Radiology; 1996; 881655294 | 384 | 47(Range: 14–88) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Cross-sectional | 8 | |||

| Dupuy DE; Academic Radiology; 1996; 895918157 | 7 | TKA patients: (Range: 64–75); Asymptomatic: 35(Range: 25–35) | 3 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 6 | ||

| Kenny C; Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research; 1997; 918621595 | 136 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Case control | 6 | ||||

| Breitenseher MJ; Acta Radiologica; 1997; 933224896 | 60 | 12 | 48 | 37(14.3), (Range: 15–68) | 30(50%) | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 5 |

| Ostergaard M; British Journal of Rheumatology; 1997; 940286097 | 46 | 14 | 47 | 70(Range: 24–85) | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 7 | |

| Trattnig S; Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography; 1998; 944875498 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 72.2(Range: 62–82) | 18 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 8 |

| Kawahara Y; Acta Radiologica; 1998; 952944062 | 72 | 58(Range: 41–74) | 46 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 6 | ||

| Drape JL; Radiology; 1998; 964679263 | 43 | 43 | 0 | 63(Range: 53–78) | 30 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 5 |

| Eckstein F; Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research; 1998; 967804256 | 8 | 0 | 8 | 50.6(Range: 39–64) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 7 | |

| Uhl M; European Radiology; 1998; 972442358 | 22 | (Range: 50–72) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 5 | |||

| Boegard T; Acta Radiologica - Supplementum; 1998; 975912199 | 61 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

5 | ||||

| Bachmann GF; European Radiology; 1999; 993339964 | 320 | 29.3(8.7), (Range: 13–56) | 122 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 7 | ||

| Cicuttini F; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 1999; 10329301100 | 28 | Males: 40.4(Range: 42–58); Females: 31.2(8.6); | 11 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 7 | ||

| Boegard T; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 1999; 10343536101 | 58 | Women: 40.4(Range: 42–58); Men: 57(49.5), (Range: 41–57) | 29 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 6 | ||

| Adams JG; Clinical Radiology; 1999; 1048421644 | 62 | 32 | 30 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Case control | 8 | ||

| Pham XV; Revue du Rhumatisme; 1999; 10526380102 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 67.2(7.34), (Range: 57–80) | 6 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Cross-sectional | 13 |

| Gale DR; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 1999; 1055885043 | 291 | 233 | 58 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Case control | 10 | ||

| Kladny B; International Orthopaedics; 1999; 1065329059 | 26 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 6 | ||||

| Zanetti M; Radiology; 2000; 10831707103 | 16 | 16 | 0 | 67(Range: 43–79) | 15 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Cross-sectional | 6 |

| Jones G; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2000; 11083279104 | 92 | 92 | 0 | Boys: 12.8(2.7); Girls: 12.6(2.9) | 43 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 13 |

| McCauley TR; American Journal of Roentgenology; 2001; 11159074105 | 193 | 40(Range: 11–86) | 83 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Cross-sectional | 8 | ||

| Wluka AE; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2001; 11247861106 | 81 | 42 | 39 | Cases: 58(6.1); Controls: 56(5.4) | 81(100%) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 16 |

| Felson DT; Annals of Internal Medicine; 2001; 1128173614 | 401 | 401 | 0 | 66.8 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Cross-sectional | 13 | |

| Hill CL; Journal of Rheumatology; 2001; 1140912715 | 458 | 433 | 25 | 67 | (34%) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Case control | 13 |

| Kawahara Y; Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography; 2001; 11584226107 | 35 | 57(Range: 33–70) | 23 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 8 | ||

| Arokoski JP; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2002; 11796401108 | 57 | 27 | 30 | Cases: 56.2(4.9), (Range: 47–64); Controls: 56.3(4.5), (Range: 47–64) | 0 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 8 |

| Bergin D; Skeletal Radiology; 2002; 11807587109 | 60 | 30 | 30 | Cases: 50; Controls: 57 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Case control | 9 | |

| Beuf O; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2002; 11840441110 | 46 | 18 | 28 | Mild OA: 68(9.1); Severe OA: 70(6.3) | 17 | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 5 |

| Arokoski MH; Journal of Rheumatology; 2002; 12375331111 | 57 | 27 | 30 | Cases: 56.2(4.9), (Range: 47–64); Controls: 56.3(4.5), (Range: 47–64) | 0 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 8 |

| Bhattacharyya T; Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery - American Volume; 2003; 1253356516 | 203 | 154 | 49 | Cases: 65; Controls: 67 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Case control | 9 | |

| Link TM; Radiology; 2003; 1256312817 | 50 | 50 | 0 | 63.7(11.5), (Range: 43–81) | 30 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Cross-sectional | 6 |

| Tiderius CJ; Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; 2003; 12594751112 | 17 | 50(Range: 35–70) | 4 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 6 | ||

| Cicuttini FM; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2003; 1263242128 | 252 | 60.2(10) | 157962%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 9 | ||

| Cicuttini FM; Clinical & Experimental Rheumatology; 2003; 12673893113 | 81 | 42 | 39 | ERT: 58(6.1); Controls: 56(5.4) | 81(100%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Case control | 12 |

| Sowers MF; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2003; 1280147818 | 120 | 60 | 60 | no OAK, no Pain: 45(0.8); OAK, no Pain: 46(0.6); No OAK, Pain: 47(0.8); OAK and Pain: 47(0.7) | (100%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Case control | 11 |

| McGibbon CA; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2003; 1281461160 | 4 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 5 | ||||

| Cicuttini FM; Clinical & Experimental Rheumatology; 2003; 1284605046 | 157 | 157 | 0 | 62(10) | (62%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 10 |

| Felson DT; Annals of Internal Medicine; 2003; 1296594151 | 256 | 256 | 0 | Followed: 66.2(9.4); Not followed: 67.8(9.6) | (38.3%) | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Longitudinal prospective |

11 |

| Tarhan S; Clinical Rheumatology; 2003; 14505208114 | 74 | 58 | 16 | OA Patients: 57.4(8.5), (Range: 45–75); Healthy controls: 59.1(5.8), (Range: 46–77) | 60 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Case control | 8 |

| Hill CL; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2003; 1455808919 | 451 | 427 | Knee pain/ROA/Male: 68.3; Knee pain/ROA/Female: 65; No knee pain/ROA/Male: 66.8; No knee pain/ROA/Female: 66.1 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Cross-sectional | 10 | ||

| Kim YJ; Journal of Bone & Joint Surgery - American Volume; 2003; 14563809115 | 43 | 30(Range: 11–47); Median = 31 | 40 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 5 | ||

| Lindsey CT; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2004; 1472386829 | 74 | 33 | 21 | Controls: 34.2(12.5); OA1 (KL1/2): 62.7(10.9); OA2(KL3/4): 66.6(11.6) | 39 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Case control | 8 |

| Jones G; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2004; 1472387647 | 372 | 186 | 186 | 45(Range: 26–61) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Case control | 9 | |

| Raynauld JP; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2004; 1487249048 | 32 | 32 | 0 | 62.9(8.2) | (74%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

10 |

| Wluka AE; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2004; 1496296020 | 132 | 132 | 0 | 63.1(Range: 41–86) | 71(54%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

10 |

| Cicuttini F; Rheumatology; 2004; 1496320152 | 117 | 117 | 0 | 67(10.6) | (58%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

12 |

| Peterfy CG; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2004; 14972335116 | 19 | 19 | 0 | 61(8) | 4 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Other | 5 |

| Graichen H; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2004; 15022323117 | 21 | 21 | 0 | 70.6(7.7), (Range: 58–86) | 17 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 6 |

| Dashti M; Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology; 2004; 15163109118 | 174 | 117 | 57 | 61.6(9.5) | 123(70.7%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 11 |

| Arokoski JP; Journal of Clinical Densitometry; 2004; 15181262119 | 57 | 27 | 30 | Cases: 56.2(4.9), Range: (47–64); Controls: 56.3(4.5), (Range: 47–64) | 0 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 9 |

| Dunn TC; Radiology; 2004; 15215540120 | 55 | 48 | 7 | Healthy: 38(Range: 22–71); Mild OA: 63(Range: 46–81); Severe OA: 67 (Range: 43–88) | 30 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 8 |

| Regatte RR; Academic Radiology; 2004; 15217591121 | 14 | 6 | 8 | Asymptomatic: 33.5(Range: 22–45); Symptomatic: 45.5(Range: 28–63) | 2 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 7 |

| Baysal O; Swiss Medical Weekly; 2004; 15243849122 | 65 | 65 | 0 | 53.1(7), (Range: 45–75) | 65(100%) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 7 |

| Lerer DB; Skeletal Radiology; 2004; 15316679123 | 205 | 46.5(Range: 15–88); Median = 46 | 113 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 6 | ||

| Berthiaume MJ; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2005; 1537485578 | 32 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

10 | ||||

| King KB; Magnetic Resonance Imaging; 2004; 15527998124 | 16 | 16 | 0 | Males: Median = 58.5, (11.3), (Range: 43–76); Females: Median = 70 (14.4), (Range: 46–88) | 8(50%) | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 7 |

| Carbone LD; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2004; 15529367125 | 818 | Non-users: 74.8(2.94); Antiresportive users: 74.8(2.9) | 818(100%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 11 | ||

| Cicuttini F; Journal of Rheumatology; 2004; 15570649126 | 123 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

6 | ||||

| Wluka AE; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2005; 1560174238 | 149 | 68 | 81 | Normal: 57(5.8); OA: 63(10.3) | 1499(100%) | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

13 |

| Ding C; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2005; 1572788549 | 372 | 162 | 210 | No cartilage defects: 43.6(7.1); Any cartilage defect: 47(6.1) | (56.5%) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 9 |

| Hill CL; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2005; 1575106445 | 433 | 360 | 73 | Cases males: 68.2; Cases females: 65; Control males: 66.8; Control females: 65.8 | 143 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Case control | 12 |

| Kornaat PR; European Radiology; 2005; 15754163127 | 205 | 205 | 0 | Median = 60; (Range: 43–77) | 163(80%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 8 |

| Zhai G; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2005; 15818695128 | 151 | 23 | 128 | Men: 64(8.1); Women: 62(7.7) | 72 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 8 |

| Cicuttini F; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2005; 1592263450 | 28 | 28 | 0 | 62.8(9.8) | (57%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

10 |

| Blankenbaker DG; Skeletal Radiology; 2005; 15940487129 | 247 | 74 | 173 | 44 | 126 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Cross-sectional | 6 |

| Huh YM; Korean Journal of Radiology; 2005; 15968151130 | 94 | 73 | 21 | RA group: 49.2 (Range: 37–76), Median = 48; OA group: 57.8 (Range: 40–80), Median = 58 | 73 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Retrospective |

7 |

| von Eisenhart-Roth; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2006; 15975965131 | 26 | 26 | 0 | 70.4(7.6), (Range: 58–86) | 20 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 5 |

| Tan AL; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2005; 16052535132 | 58 | 40 | 18 | Early OA: 56 (Range: 49–69); Chronic OA: 60 (Range: 51–68); Hand OA: 60 (Range: 46–72); | 44 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Cross-sectional | 7 |

| Lo GH; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2005; 16145676133 | 268 | 80 | 188 | No BMLs: 64.8(8.5); Medial BMLs: 68.3(7); Lateral BMLs: 66.6(9.5) | (59%) | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Cross-sectional | 10 |

| Li X; Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; 2005; 16155867134 | 19 | 9 | 10 | Cases: Median = 52, (Range: 18–72); Controls: Median = 30, (Range: 22–74) | 8 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 7 |

| Rhodes LA; Rheumatology; 2005; 16188949135 | 35 | 35 | 0 | Median = 63; (Range: 49–77) | 23 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 9 |

| Williams A; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2005; 1625502432 | 31 | 31 | 0 | 67(10.4), 9 (Range: 45–86) | 24(77%) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 9 |

| Loeuille D; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2005; 16255041136 | 39 | 39 | 0 | 56.4(12.71) | (56.4%) | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 10 |

| Roos EM; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2005; 16258919137 | 30 | 45.8(3.3) | 10(33.3%) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Randomized controlled trial |

17 | ||

| Hunter DJ; Journal of Rheumatology; 2005; 1626570253 | 132 | 162 | 0 | 33.5(9.7) | (44.2%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Cross-sectional | 8 |

| Nojiri T; Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy; 2006; 1639556433 | 28 | 9 | 21 | 40.3(Range: 16–74) | 17 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 7 |

| Kimelman T; Invest Radiol; 2006; 16428993138 | 7 | 4 | 3 | Healthy controls: 23; OA cases: 56 | 4 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 6 |

| Sengupta M; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2006; 16442316139 | 217 | 217 | 0 | 67.3(9.1) | (30%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | Cross-sectional | 7 |

| Hunter DJ; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2006; 1650893081 | 257 | 257 | 0 | 66.6(9.2), (Range: 47–93) | (41.6%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

10 |

| Hunter DJ; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2006; 1664603783 | 217 | 217 | 0 | 66.4(9.4) | (44%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

10 |

| Grainger AJ; European Radiology; 2007; 16685505140 | 43 | 43 | 0 | 64(Range: 48–75) | 19 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 8 |

| Cashman PM; IEEE Transactions on Nanobioscience; 2002; 16689221141 | 27 | 10 | 17 | OA patients: (Range: 45–73); Similar age controls: (Range: 50–65); Young healthy controls: (Range: 21–32); | 8(29.6%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 6 |

| Torres L; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2006; 1671331021 | 143 | 143 | 0 | 70(10) | (78%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cross-sectional | 9 |

| Kornaat PR; Radiology; 2006; 1671446322 | 205 | 97 | 103 | 60 (Range: 43–77) | 163(80%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 9 |

| Bamac B; Saudi Medical Journal; 2006; 16758050142 | 46 | 36 | 10 | Cases: 41.9 (Range: 20–67); Controls: 39.7 (Range: 21–66) | 25 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Case control | 8 |

| Boks SS; American Journal of Sports Medicine; 2006; 16861575143 | 134 | 136 | 132 | 40.8(Range: 18.8–63.8) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Cross-sectional | 7 | |

| Koff MF; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2007; 1694931334 | 113 | 113 | 0 | 56(11), (Range: 33–82) | 84 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 8 |

| Nakamura M; Magnetic Resonance Imaging; 2006; 1707133639 | 63 | 51.8 (Range: 40–59) | 42 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 6 | ||

| Folkesson J; IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging; 2007; 17243589144 | 139 | 56(Range: 22–79) | (59%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 7 | ||

| Li X; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2007; 1730736535 | 26 | 10 | 16 | Healthy: 41.3 (Range: 22–74); OA patients: 55.9 (37–72) | 11 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Case control | 7 |

| Iwasaki J; Clinical Rheumatology; 2007; 17322963145 | 26 | 26 | 0 | 63.8(Rang: 49–82) | 18 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 5 |

| Dam EB; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2007; 1735313231 | 139 | Evaluation set: 55(Range: 21–78); Scan-rescan set: 61 (Range: 26–75) | (54.5%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 9 | ||

| Tiderius CJ; Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; 2007; 17390362146 | 18 | 10 | 8 | Controls: 28(Range: 20–47); Cases: 39 (Range: 25–58) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 6 | |

| Baranyay FJ; Seminars in Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2007; 17391738147 | 297 | 297 | 58(5.5) | (63%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Cross-sectional | 16 | |

| Issa SN; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2007; 1739422554 | 146 | 146 | 0 | 70 | 109 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 8 |

| Hanna F; Menopause; 2007; 17413649148 | 176 | 0 | 176 | 52.3(6.6), (Range: 40–67) | 176(100%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 13 |

| Hunter DJ; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2008; 1747299523 | 71 | 67.9(9.3) | (28.2%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Other | 8 | ||

| Hill CL; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2007; 1749109624 | 270 | 270 | 0 | 66.7(9.2) | 112 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

9 |

| Qazi AA; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2007; 17493841149 | 71 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 8 | ||||

| Lammentausta E; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2007; 17502160150 | 14 | 55(18) | 2 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Other | 5 | ||

| Guymer E; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2007; 17560134151 | 176 | 0 | 176 | 52.3(6.6) | 176(100%) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Cross-sectional | 11 |

| Nishii T; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 17644363152 | 33 | 23 | 10 | Volunteers: 34(Range: 23–51); Patients: 40(Range: 22–69) | 33(1005) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 8 |

| Janakiramanan N; Journal of Orthopaedic Research; 2008; 1776345155 | 202 | 74 | 128 | 61(9) | (73%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 11 |

| Lo GH; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 17825586153 | 845 | 170 | 63.6(8.8) | (58%) | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 10 | |

| Davies-Tuck M; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 17869546154 | 100 | 100 | 0 | 63.3(10.2) | 61(61%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective |

11 |

| Qazi AA; Academic Radiology; 2007; 17889338155 | 159 | (Range: 21–81) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 8 | |||

| Folkesson J; Academic Radiology; 2007; 17889339156 | 71 | 56(Range: 22–79) | (59%) | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 7 | ||

| Englund M; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2007; 1805020140 | 310 | 102 | 208 | Cases: 62.9(8.3); Controls: 61.2(8.3) | 211(68%) | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Case control | 15 |

| Kamei G; Magnetic Resonance Imaging; 2008; 18083319157 | 37 | 27 | 0 | Cartilage defect: 51.6(Range: 42–61); No cartilage defect: 54.5(Range: 45–61) | 20 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Case control | 7 |

| Li W; Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging; 2008; 18183573158 | 29 | 19 | 10 | OA subjects: 61.7(Range: 40–86); Controls: 31 (Range: 18–40) | 19 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 5 |

| Amin S; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 1820362986 | 265 | 265 | 67(9) | (43%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Longitudinal Prospective |

11 | |

| Taljanovic MS; Skeletal Radiology; 2008; 18274742159 | 19 | 19 | 0 | 66 | 8 | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 8 |

| Oda H; Journal of Orthopaedic Science; 2008; 18274849160 | 161 | 58.5(Range: 11–85) | 98 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Cross-sectional | 8 | ||

| Hanna FS; Arthritis Research & Therapy; 2008; 18312679161 | 176 | 52.3(6.6) | (100%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 10 | ||

| Reichenbach S; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 1836741541 | 964 | 217 | 747 | 63.3 | (57%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 8 |

| Petterson SC; Medicine & Science in Sports & Exercise; 2008; 18379202162 | 123 | 123 | 0 | 64.9(8.5) | 67 | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 11 |

| Bolbos RI; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 18387828163 | 32 | 16 | 16 | Cases: 47.2(11.54), (Range: 29–72); Controls: 36.3(10.54), (Range: 27–56) | 14 | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Case control | 7 |

| Quaia E; Skeletal Radiology; 2008; 18404267164 | 35 | 35 | 0 | 42(17), (Range: 22–67) | 14 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 6 |

| Folkesson J; Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; 2008; 1850684542 | 245 | 143 | KL0: 48(Range: 21–78); KL1: 62(Range: 37–81); KL2: 67(Range: 47–78); KL3&4: 68(Range: 58–78) | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Other | 12 | ||

| Mills PM; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 18515157165 | 49 | 25 | 24 | APMM: 46.8(5.3); Controls: 43.6(6.6) | 18(36.7%) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 12 |

| Dore D; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 18515160166 | 50 | 50 | 64.5(7.1) | 23 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 9 | |

| Mutimer J; Journal of Hand Surgery; 2008; 18562375167 | 20 | 20 | 0 | 47 (Range: 26–69) | 9 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 6 |

| Amin S; Journal of Rheumatology; 2008; 18597397168 | 192 | 192 | 69(9) | 0. | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 10 | |

| Li X; Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging; 2008; 18666183169 | 38 | 13 | 25 | Healthy: 28.5 (Range: 20–34); Knee OA or injury: 37.4 (Range: 20–66) | 10 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Other | 7 |

| Pelletier JP; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 1867238625 | 27 | 1 | 64.1(9.6) | 14 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Other | 9 | |

| Stahl R; European Radiology; 2009; 18709373170 | 37 | 17 | 20 | Mild OA: 54(9.98); Healthy control: 33.6(9.44) | 19 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 10 |

| Brem MH; Acta Radiologica; 2008; 18720084171 | 23 | 23 | 0 | 55.5(10.3) | 8 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Other | 6 |

| Lancianese SL; Bone; 2008; 18755303172 | 4 | 80(14) | 3 | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 5 | ||

| Englund M; New England Journal of Medicine; 2008; 1878410026 | 991 | 171 | 62.3(8.6), (Range: 50.1–90.5) | 565(57%) | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Cross-sectional | 10 | |

| Mamisch TC; Magnetic Resonance in Medicine; 2008; 18816842173 | 26 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 7 | ||||

| Rauscher I; Radiology; 2008; 18936315174 | 60 | 37 | 23 | Healthy controls: 34.1(10); Mild OA: 52.5(10); Severe OA: 61.6(11.6) | 32 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Case control | 9 |

| Li W; Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging; 2009; 19161210175 | 31 | 17 | 14 | OA patients: 61.8(Range: 40–86); Healthy controls: 29.2(Range: 18–40) | 21 | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 7 |

| Choi JW; Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography; 2009; 19188805176 | 36 | 39.7(Range: 8–69) | 21 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Longitudinal Retrospective |

7 | ||

| Chen YH; Journal of Computer Assisted Tomography; 2008; 19204464177 | 96 | 25 | 71 | OA patients: 56; Non-OA: 46 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Case control | 8 |

The analysis included data from 142 manuscripts. The mean Downs criteria score for these manuscripts was 8.3 (range 3–17). What follows below are important excerpts from this data pertaining to different aspects of concurrent validity. The data is further summarized in Table II to discretely identify the associations examined and those where a significant association was found.

Table II.

Summary of Concurrent Validity of MRI in OA

| Outcome of interest | Number of studies examining this outcome | Number of studies finding significant associations (P < .05) |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | 21 studies | 13 of 21 (62%) |

| Radiographic features | 43 studies | 39 of 43 (90%) |

| Radiographic joint space | 9 studies | 9 of 9 (100%) |

| Alignment | 10 studies | 9 of 10 (90%) |

| CT | 4 studies | 4 of 4 (100%) |

| Histology/Pathology | 5 studies | 3 of 5 (60%) |

| Arthroscopy | 7 studies | 5 of 7 (71%) |

Relation to symptoms

21 studies examined the concurrent relation of MRI findings in OA to symptoms. Of these, 62% demonstrated a statistically significant association, defined as P < 0.05. Bone marrow lesions were found in 272 of 351 (77.5%) persons with painful knees compared with 15 of 50 (30%) persons with no knee pain (P < 0.001). Large lesions were present almost exclusively in persons with knee pain (35.9% vs 2%; P < 0.001). After adjustment for severity of radiographic disease, effusion, age, and sex, lesions and large lesions remained associated with the occurrence of knee pain [odds ratio, 3.31 (95% confidence interval (CI), 1.54–7.41)]. Using the same analytical approach, large lesions were also strongly associated with the presence of pain [odds ratio, 5.78 (CI, 1.04–111.11)]. Among persons with knee pain, bone marrow lesions were not associated with pain severity14.

After adjusting for the severity of radiographic OA, there was a difference between those with and without knee pain in prevalence of moderate or larger effusions (P < 0.001) and synovial thickening, independent of effusion (P < 0.001). Among those with small (grade 1) or no knee (grade 0) effusion, those with knee pain had a prevalence of synovial thickening of 73.6% compared to 21.4% of those without knee pain (P < 0.001). There was a significant difference in visual analogue scale (VAS) pain scores in those with synovial thickening compared to those without synovial thickening, after adjustment for radiographic severity, size of effusion, age, sex, and BMI. The mean pain score in those with synovial thickening after adjustment for radiographic severity and size of effusion was 47.2 mm [standard error (SE) 6.0], compared to 28.2 mm (SE 2.8) in those without synovial thickening (P = 0.006)15.

A medial or lateral meniscal tear was a very common finding in the asymptomatic subjects (prevalence, 76%) but was more common in the patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis (91%) (P < 0.005). There was no significant difference with regard to the pain or WOMAC score between the patients with and those without a medial or lateral meniscal tear in the osteoarthritic group (P = 0.8 to 0.9 for all comparisons)16.

Significant differences between WOMAC scores were found for the grades of cartilage lesions (P < 0.05) but not bone marrow edema pattern, and ligamentous and meniscal lesions17.

Bone marrow lesions >1 cm were more frequent (OR = 5.0; 95% CI = 1.4, 10.5) in the painful knee OA group than all other groups. While the frequency of BME lesions was similar in the painless OA and painful OA groups, there were more lesions, >1 cm, in the painful OA group. Full-thickness cartilage defects occurred frequently in painful OA. Women with radiographic OA, full-thickness articular cartilage defects, and adjacent subchondral cortical bone defects were significantly more likely to have painful knee OA than other groups (OR = 3.2; 95% CI = 1.3, 7.6)18.

Peripatellar lesions (prepatellar or superficial infrapatellar) were present in 12.1% of the patients with knee pain and ROA, in 20.5% of the patients with ROA and no knee pain, and in 0% of subjects with neither ROA nor knee pain (P = 0.116). However, other periarticular lesions (including bursitis and iliotibial band syndrome) were present in 14.9% of patients with both ROA and knee pain, in only 3.9% of patients with ROA but no knee pain, and in 0% of the group with no knee pain and no ROA (P = 0.004)19.

More severe symptoms relating to knee OA (pain, stiffness, and function) are weakly inversely related to tibial cartilage volume. Patients with lower cartilage volume had more severe symptoms of knee OA than those with higher cartilage volume20.

The increase in median pain from median quantile regression, adjusting for age and BMI, was significant for bone attrition (1.91, 95% CI 0.68, 3.13), bone marrow lesions (3.72, 95% CI 1.76, 5.68), meniscal tears (1.99, 95% CI 0.60, 3.38), and grade 2 or 3 synovitis/effusion vs grade 0 (9.82, 95% CI 0.38, 19.27). The relationship with pain severity was of borderline significance for osteophytes and cartilage morphology and was not significant for bone cysts or meniscal subluxation. When compared to the pain severity in knees with high scores for both bone attrition and bone marrow lesions (median pain severity 40 mm), knees with high attrition alone (30 mm) were not significantly different, but knees with high bone marrow lesion without high attrition scores (15 mm) were significantly less painful21.

A large joint effusion was associated with pain (OR, 9.99; 99% CI: 1.28, 149) and stiffness (OR, 4.67; 99% CI: 1.26, 26.1). The presence of an osteophyte in the patellofemoral compartment (OR, 2.25; 99% CI: 1.06, 4.77) was associated with pain. All other imaging findings, including focal or diffuse cartilaginous abnormalities, subchondral cysts, bone marrow edema, subluxation of the meniscus, meniscal tears, or Baker cysts, were not associated with symptoms22.

Maximal bone marrow lesion (BML) size on the Boston Leeds Osteoarthritis Score (BLOKS) scale had a positive linear relation with VAS pain (P for linear trend = 0.04)23.

No correlation of baseline synovitis with baseline pain score (r = 0.09, P = 0.17)24.

No relation between baseline synovitis score and VAS pain score (r = 0.11, P = 0.60)25.

In the group of persons with radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis (Kellgren–Lawrence grade 2 or higher), the prevalence of a meniscal tear was 63% among those with knee pain, aching, or stiffness on most days and 60% among those without these symptoms (P = 0.75); the corresponding prevalences in the group without radiographic evidence of osteoarthritis were 32% and 23% (P = 0.02). The majority of the meniscal tears – 180 of 297 (61%) were in subjects who had not had any pain, aching, or stiffness in the previous month26.

Relation to radiographic features

43 studies examined the concurrent relation of MRI findings in OA to radiographic features. Of these, 90% demonstrated a statistically significant association, defined as P < 0.05.

Relation of quantitative cartilage morphometry measures to radiographic abnormalities

Significant differences in lateral and medial femorotibial cartilage thickness were found between those with and without radiographic OA. Significant cartilage thinning could be detected by MRI in patients with OA, even when the joint space was normal radiographically27.

For every increase in grade of lateral tibiofemoral osteophytes the lateral tibial cartilage volume was significantly reduced by 255 mm3, after adjustment. There was a reduction of 77 mm3 in medial tibial cartilage volume for every increase in grade of medial tibiofemoral osteophytes, but this finding was only of borderline statistical significance28.

Cartilage volume and thickness were less in patients with OA compared to normal controls (P < 0.1)29.

Kellgren and Lawrence (KLG)2 participants displayed, on average, thicker cartilage than healthy controls in the medial femorotibial compartment [particularly anterior subregion of the medial tibia (MT) and peripheral (external, internal) subregions of the medial femur], and in the lateral femur. KLG3 participants displayed significantly thinner cartilage than KLG0 participants in the medial weight-bearing femur (central subregion), in the external subregion of the MT, and in the internal subregion of the lateral tibia30.

Mean cartilage signal intensity provided a clear separation of healthy from KLG1 (P = 0.0009). Quantification of cartilage homogeneity by entropy was able to clearly 11 separate healthy from OA subjects (P = 0.0003). Furthermo121re, entropy was also able to separate healthy from KL 1 subjects (P = 0.0004)31.

Relation of other MRI measures to radiographic abnormalities

Significant difference (P = 0.002) in the average T(1rho) within patellar and femoral cartilage between controls (45.04 ± 2.59 ms) and osteoarthritis patients (53.06 ± 4.60 ms). A significant correlation was found between T(1rho) and T(2); however, the difference of T(2) was not statistically significant between controls and osteoarthritis patients31.

Trend toward a lower dGEMRIC index with increasing KLG; the spared compartments of knees with a KLG grade 2 had a higher dGEMRIC index than those of knees with a KLG grade 4 (mean 425 msec vs 371 msec; P < 0.05)32.

All cases demonstrating decreased T1 values on dGEMRIC, showed abnormal arthroscopic or direct viewing findings. The diagnosis of damage in articular cartilage was possible in all 16 cases with radiographic KLG 1 on dGEMRIC, while the intensity changes were not found in 10 of 16 cases on Proton density Weighted Image (PDWI)33.

No differences of T2 values were found across the stages of OA (P = 0.25), but the factor of BMI did have a significant effect P < 0.0001) on T2 value34.

Average T(1rho) and T(2) values were significantly increased in OA patients compared with controls [52.04 ± 2.97 ms vs 45.53 ± 3.28 ms with P = 0.0002 for T(1rho), and 39.63 ± 2.69 ms vs 34.74 ± 2.48 ms with P = 0.001 for T(2)]. Increased T(1rho) and T(2) values were correlated with increased severity in radiographic and MR grading of OA. T(1rho) has a larger range and higher effect size than T(2), 3.7 vs 3.035.

Statistically significant correlation between radiography and MR cartilage loss in the medial (r 0.7142, P .0001) and lateral compartments (r = 0.4004, P .0136). Significant correlations also found between radiographic assessment of sclerosis and osteophytes and those found on MRI36.

Patients in whom plain radiographs, MRI, and arthroscopy were compared, the plain radiographs and MRI significantly underestimated the extent of cartilage abnormalities37.

Presence of synovial thickening was more likely with increasing KLG, from 24.0% in those with KLG 0–78.3% in those with LG 3/4 (P < 0.001)15.

Higher KLG was correlated with a higher frequency of meniscal tears (r = 0.26, P < 0.001)16.

KLG correlated significantly (P < 0.05) with the grade of cartilage lesions, and a substantially higher percentage of bone marrow and meniscal lesions with higher KLG found on MR images17.

Women with osteoarthritis had larger medial and lateral tibial plateau bone area [mean (SD): 1850 (240) mm2 and 1279 (220) mm2, respectively] than healthy women [1670 (200) mm2 and 1050 (130) mm2] (P < 0.001 for both differences). For each increase in grade of osteophyte, an increase in bone area was seen of 146 mm2 in the medial compartment and 102 mm2 in the lateral compartment38.

Statistically significant correlations were observed between the medial tibial spur classification on X-ray, the medial meniscal displacement rate on MRI and the medial meniscal signal change classification on MRI39.

Meniscal damage was mostly present in knees with OA and demonstrates a relation to KLG40.

Bone attrition of the tibiofemoral joint, scored >1, was found in 228 MRIs (23.6%) and in 55 radiographs (5.7%). Moderate to strong correlation between MRIs and radiographs for bone attrition of the tibiofemoral joint (r = 0.50, P < 0.001)41.

Surface curvature of articular cartilage for both the fine- and coarse-scale estimates were significantly higher in the OA population compared with the healthy population, with P < 0.001 and P < 0.001, respectively42.

The prevalence of meniscal damage was significantly higher among subjects with radiographic evidence of tibiofemoral osteoarthritis (KLG 2 or higher) than among those without such evidence (82% vs 25%, P < 0.001), and the prevalence increased with a higher KLG (P < 0.001 for trend). Among persons with radiographic evidence of severe osteoarthritis (KLG 3 or 4 in their right knee), 95% had meniscal damage26.

Relation to radiographic joint space width

Nine studies examined the concurrent relation of MRI findings in OA to radiographic joint space. Of these, 100% demonstrated a statistically significant association, defined as P < 0.05.

Strong correlation between the degree of medial meniscal subluxation and the severity of medial joint space narrowing (JSN) (r = 0.56, P = 0.0001)43.

Meniscal extrusion identified in all 32 patients with JSN (KLG 1–4). Definite thinning or loss of articular cartilage was identified in only 15 of the 32 cases. In 17 patients with radiographic JSN (KLG 1–3) and meniscal extrusion, no loss of articular cartilage was observed. A statistically significant correlation (P < 0.001) was observed between KLG and degree of meniscal extrusion and cartilage thinning on MRI44.

For each increase in grade of JSN, tibial plateau bone area increased by 160 mm2 in the medial compartment and 131 mm2 in the lateral compartment (significance of regression coefficients all P < 0.001)38.

Persons with symptomatic knee OA with ACL rupture had more severe radiologic OA (P < 0.0001) and were more likely to have medial JSN (P < 0.0001) than a control sample45.

Compartments of the knee joint without JSN had a higher dGEMRIC index than those with any level of narrowing (mean 408 msec vs 365 msec; P = 0.001). In knees with 1 unnarrowed (spared) and 1 narrowed (diseased) compartment, the dGEM-RIC index was greater in the spared vs the diseased compartment (mean 395 msec vs 369 msec; P = 0.001)32.

Grade of JSN as measured on skyline and lateral patellofemoral radiographs was inversely associated with patella cartilage volume. After adjusting for age, gender and body mass index, for every increase in grade of skyline JSN (0–3), the patella cartilage volume was reduced by 411 mm3. For every increase in lateral patellofemoral JSN grade (0–3), the adjusted patella cartilage volume was reduced by 125 mm3. The relationship was stronger for patella cartilage volume and skyline JSN (r = −0.54, P < 0.001) than for lateral patellofemoral JSN (r = −0.16, P = 0.015)46.

Grade one medial JSN was associated with substantial reductions in cartilage volume at both the medial and lateral tibial and patellar sites within the knee (adjusted mean difference 11–13%, all P < 0.001)47.

Cartilage volume in the medial compartment and the narrowest JSW obtained by radiography at baseline in 31 knee OA patients, revealed that some level of correlation exists between these two measurements (r = 0.46, P < 0.007)48.

Knee cartilage defects are inconsistently associated with JSN after adjustment for osteophytes but consistently with knee cartilage volume (beta: −0.27 to −0.70/ml; OR: 0.16–0.56/ml, all P < 0.01 except for OR at lateral tibial cartilage site P = 0.06)49.

Moderate, but statistically significant, correlation between JSW and femoral and tibial cartilage volumes in the medial tibiofemoral joint, which was strengthened by adjusting for medial tibial bone size (R = 0.58–0.66, P = 0.001)50.

JSN seen on both medial and lateral radiographs of the tibiofemoral joint was inversely associated with the respective tibial cartilage volume. This inverse relationship was strengthened with adjustment for age, sex, body mass index (BMI), and bone size. After adjustment for these confounders, for every increase in JSN grade (0–3), the medial tibial cartilage volume was reduced by 257 mm3 (95% CI 193–321) and the lateral tibial cartilage volume by 396 mm3 (95% CI 283–509). The relationship between mean cartilage volume and radiologic grade of JSN was linear28.

Relation to alignment

10 studies examined the concurrent relation of MRI findings in OA to alignment. Of these, 90% demonstrated a statistically significant association, defined as P < 0.05.

Valgus-aligned knees tended to have lower dGEMRIC values laterally, and varus-aligned knees tended to have lower dGEMRIC values medially; as a continuous variable, alignment correlated with the lateral: medial dGEMRIC ratio (Pearson’s R = 0.43, P = 0.02)32.

Limbs with varus alignment, especially if marked (≥7 degrees), had a remarkably high prevalence of medial lesions compared with limbs that were neutral or valgus (74.3% vs 16.4%; P < 0.001 for relation between alignment and medial lesions). Conversely, limbs that were neutral or valgus had a much higher prevalence of lateral lesions than limbs that were in the most varus group (29.5% vs 8.6%; P = 0.002 for alignment and lateral lesions)51.

Medial tibial and femoral cartilage volumes increased as the angle decreased (i.e., was less varus). Similarly, in the lateral compartment there was an inverse association at baseline between tibial and femoral cartilage volumes and the measured knee angle52.

The main univariate determinants of varus alignment in decreasing order of influence were medial bone attrition, medial meniscal degeneration, medial meniscal subluxation, and medial tibiofemoral cartilage loss. Multivariable analysis revealed that medial bone attrition and medial tibiofemoral cartilage loss explained more of the variance in varus malalignment than other variables. The main univariate determinants of valgus malalignment in decreasing order of influence were lateral tibiofemoral cartilage loss, lateral osteophyte score, and lateral meniscal degeneration53.

Correlation between medial meniscal displacement rate on MRI and the femorotibial angle (r = 0.398)39.

Worsening in the status of each medial lesion cartilage morphology, subarticular bone marrow lesions, meniscal tear, meniscal subluxation, and bone attrition was associated with greater varus malalignment54.

For every one degree increase in a valgus direction, there was an associated reduced risk of the presence of cartilage defects in the medial compartment of subjects with knee OA (P = 0.02). Moreover, for every one degree increase in a valgus direction, there was an associated increased risk of the presence of lateral cartilage defects in the OA group (P = 0.006)55.

Relation to CT

Four studies examined the concurrent relation of MRI findings in OA to CT. Of these, 100% demonstrated a statistically significant association, defined as P < 0.05. MR frequently showed tricompartmental cartilage loss when radiography and CT showed only bicompartmental involvement in the medial and patellofemoral compartments. In the lateral compartment, MR showed a higher prevalence of cartilage loss (60%) than radiography (35%) and CT (25%) did. In the medial compartment, CT and MR showed osteophytes in 100% of the knees, whereas radiography showed osteophytes in only 60%. Notably, radiography often failed to show osteophytes in the posterior medial femoral condyle. On MR images, meniscal degeneration or tears were found in all 20 knees studied. Partial and complete tears of the anterior cruciate ligament were found in three and seven patients, respectively. MR is more sensitive than radiography and CT for assessing the extent and severity of osteoarthritic changes and frequently shows tricompartmental disease in patients in whom radiography and CT show only bicompartmental involvement. MR imaging is unique for evaluating meniscal and ligamentous disease related to osteoarthritis36.

Strong linear relationship (r = 0.998) between MRI imaging and CT arthrography. The mean absolute volume deviation between magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography arthrography was 3.3%56.

Relation to histology/pathology

Five studies examined the concurrent relation of MRI findings in OA to histology/pathology. Of these, 60% demonstrated a statistically significant association, defined as P < 0.05. Observed measurements of MRI volume of articular cartilage correlated with actual weight and volume displacement measurements with an accuracy of 82%–99% and linear correlation coefficients of 0.99 (P = 2.5e-15) and 0.99 (P = 4.4e-15)57.

The signal behavior of hyaline articular cartilage does not reflect the laminar histologic structure. Osteoarthrosis and cartilage degeneration are visible on MR images as intra-cartilaginous signal changes, superficial erosions, diffuse cartilage thinning, and cartilage ulceration58.

Comparison of data on cartilage thickness measurements with MRI with corresponding histological sections in the middle of each sector revealed a very good magnetic resonance/anatomic correlation (r = 0.88)59.

Correlation between MRI Noyes grading scores and Mankin grading scores of natural lesions was moderately high (r = 0.7) and statistically significant (P = 0.001)60.

Relation to arthroscopy

Seven studies examined the concurrent relation of MRI findings in OA to arthroscopy. Of these, 71% demonstrated a statistically significant association, defined as P < 0.05.

Moderate correlation between imaged cartilage scores and the arthroscopy scores (Pearson correlation coefficient = 0.40)37.

Spearman rank linear correlation between arthroscopic and MR cartilage grading was highly significant (P < 0.002) for each of the six articular regions evaluated. The MR and arthroscopic grades were the same in 93 (68%) of 137 joint surfaces, they were the same or differed by one grade in 123 surfaces (90%), and they were the same or differed by one or two grades in 129 surfaces (94%)61.

The overall sensitivity and specificity of MR in detecting chondral abnormalities were 60.5% (158/261) and 93.7% (89/95) respectively. MR imaging was more sensitive to the higher grade lesions: 31.8% (34/107) in grade 1; 72.4% (71/98) in grade 2; 93.5% (43/46) in grade 3; and 100% (10/10) in grade 4. The MR and arthroscopic grades were the same in 46.9% (167/356), and differed by no more than 1 grade in 90.2% (321/356) and 2 grades in 99.2% (353/356). The correlation between arthroscopic and MR grading scores was highly significant with a correlation coefficient of 0.705 (P < 0.0001)62.

Statistically significant correlation between the SFA-arthroscopic score and the SFA-MR score (r = 0.83) and between the SFA-arthroscopic grade and the SFA-MR grade (weighted kappa = 0.84). The deepest cartilage lesions graded with arthroscopy and MR imaging showed correlation in the medial femoral condyle (weighted kappa = 0.83) and in the medial tibial plateau (weighted kappa = 0.84)63.

Magnetic resonance imaging was in agreement with arthroscopy in 81% showing more degeneration but less tears of menisci than arthroscopy. Using a global system for grading the total damage of the knee joint into none, mild, moderate, or severe changes, agreement between arthroscopy and MRI was found in 82%64.

Predictive validity (Table III)

Table III.

Summary table of studies reporting data on predictive validity of MRI in knee OA

| Reference: Author, Journal, Year, PMID | Whole sample size | No. of cases | No. of controls | Age, yrs, Mean(SD), Range | No. (%)of females | Quantitative cartilage | Compositional techniques | Semi-quantitative | Cartilage | Synovium | Bone | Bone marrow lesions | Meniscus | Ligament | Study design | Score of methodological quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boegard TL; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2001; 11467896178 | 47 | Women: Median = 50, (Range: 42–57); Men: Median = 50, (Range: 41–57) | 25(53.2%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 9 | ||

| Wluka AE; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2002; 12209510179 | 123 | 123 | 0 | 63.1(10.6) | 71 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 14 |

| Cicuttini FM; Journal of Rheumatology; 2002; 12233892180 | 21 | 8 | 13 | Case: 41.3(13.2); Controls: 49.2(17.8) | 14(66.7%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Retrospective | 13 |

| Biswal S; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2002; 1242822876 | 43 | 4 | 39 | 54.4(Range: 17–65) | 21 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Longitudinal Retrospective | 8 |

| Cicuttini F; Journal of Rheumatology; 2002; 12465162181 | 110 | 110 | 0 | 63.2(10.2) | 66 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 12 |

| Pessis E; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2003; 12744942182 | 20 | 20 | 63.9(9) | 13 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 12 | |

| Felson DT; Annals of Internal Medicine; 2003; 1296594151 | 256 | 156 | 0 | Followed: 66.2(9.4); Not followed: 67.8(9.6) | (38.3%) | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 11 |

| Cicuttini FM; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2004; 1473060477 | 117 | 117 | 63.7(10.2) | (58.1%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 9 | |

| Wluka AE; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2004; 1496296020 | 132 | 132 | 0 | 63.1(Range: 41–86) | 71(54%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 10 |

| Cicuttini F; Rheumatology; 2004; 1496320152 | 117 | 117 | 0 | 67(10.6) | (58%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 12 |

| Cicuttini FM; Ann Rheum Dis; 2004; 1511571465 | 123 | 123 | 0 | Joint replacement: 64.1(9.3); No joint replacement: 63.1(10.3) | 65(52.8%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 11 |

| Dashti M; Scandinavian Journal of Rheumatology; 2004; 15163109118 | 174 | 117 | 57 | 61.6(9.5) | 123(70.7%) Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 11 | |

| Cicuttini FM; Journal of Rheumatology; 2004; 15229959183 | 102 | 102 | 0 | 63.8(10.1) | (63%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 10 |

| Berthiaume MJ; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2005; 1537485578 | 32 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 10 | ||||

| Cicuttini F; Journal of Rheumatology; 2004; 15570649126 | 123 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 6 | ||||

| Cubukcu D; Clinical Rheumatology; 2005; 15599642184 | 40 | 40 | HA group: 52.6(7.16); Saline group: 57.6(2.77) | 24(60%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Randomized controlled trial | 15 | |

| Ozturk C; Rheumatol Int; 2006;15703953185 | 47 | 47 | 0 | HA-only group: 58(7.7); HA&Cortico group: 58.1(10.3) | 39(97.5%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Randomized controlled trial | 17 |

| Wang Y; Arthritis Res Ther; 2005; 15899054186 | 126 | 126 | 63.6(10.1) | 68 | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 12 | |

| Cicuttini F; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2005; 1592263450 | 28 | 28 | 0 | 62.8(9.8) | (57%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 10 |

| Wluka AE; Rheumatology; 2005; 1603008466 | 126 | 126 | 0 | 63.6(10.1) | 68(54%) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 14 |

| Garnero P; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2005; 16145678187 | 377 | 377 | 0 | 62.5(8.1) | (76%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 11 |

| Wang Y; Rheumatology; 2006; 1618894779 | 124 | 124 | 0 | Females: 57.1(5.8); Males: 52.5(13.2) | 81(65.3%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 11 |

| Phan CM; European Radiology; 2006; 1622253368 | 40 | 34 | 6 | 57.7(15.6), (Range: 28–81) | 16 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Longitudinal Prospective | 7 |

| Hayes CW; Radiology; 2005; 16251398188 | 117 | 117 | 115 | No OA, No Pain: 44.6(10.7); OA, No Pain: 16.2(0.8); No OA, Pain: 47(0.7); OA&Pain: 47.1(0.8) | (100%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Longitudinal Prospective | 13 |

| Wang Y; Journal of Rheumatology; 2005; 16265703189 | 40 | 0 | 40 | 52.3(13) | 0 | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 11 |

| Ding C; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2005; 1632033980 | 325 | 45.2(6.5) | 190 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 10 | ||

| Bruyere O; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2006; 16396978190 | 62 | 62 | 0 | 64.9(10.3) | 49 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Longitudinal Prospective | 10 |

| Katz JN; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2006; 1641321069 | 83 | 61(11), (Range: 45–89) | 50(60%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 9 | ||

| Raynauld JP; Arthritis Research & Therapy; 2006; 1650711972 | 110 | 110 | 0 | 62.4(7.5) | (64%) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 11 |

| Hunter DJ; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2006; 1650893081 | 257 | 257 | 0 | 66.6(9.2), (Range: 47–93) | (41.6%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 10 |

| Ding C; Archives of Internal Medicine; 2006; 1656760582 | 325 | Decrease defects: 45.4(6.4); Stable defects: 44.2(7.1); Increase defects: 46.1(5.9) | (58.1%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 14 | ||

| Brandt KD; Rheumatology; 2006; 16606655191 | 30 | 20 | 10 | 62 | 29 | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Other | 10 |

| Hunter DJ; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2006; 1664603783 | 217 | 217 | 0 | 66.4(9.4) | (44%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 10 |

| Wluka AE; Arthritis Research & Therapy; 2006; 16704746192 | 105 | 105 | 0 | All eligible: 62.5 (10.7); MRI at FU: 63.8(10.6); Lost to FU: 61.6(11.3) | 59(53%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 17 |

| Hunter DJ; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2007; 16857393193 | 127 | 127 | 67(9.05) | (46.7%) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 12 | |

| Bruyere O; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2007; 1689046173 | 62 | 62 | 0 | 64.9(10.3) | 46 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Longitudinal Prospective | 10 |

| Amin S; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2007; 17158140194 | 196 | 196 | 0 | 68(9) | 0 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 13 |

| Nevitt MC; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2007; 1746912674 | 80 | 39 | 0 | 73.5(3.1) | (63.6%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 10 |

| Hill CL; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2007; 1749109624 | 270 | 270 | 0 | 66.7(9.2) | 112 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 9 |

| Pelletier JP; Arthritis Research & Therapy; 2007; 1767289171 | 110 | 110 | 0 | Q1 greatest loss global: 63.7(7.2); Q4 least loss gobal: 61.3(7.5); Q1 greatest loss_medial: 64.1 (7.4); Q1 least loss_medial: 61.6(7.8) | (68.3%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 15 |

| Davies-Tuck ML; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 17698376195 | 117 | 117 | 0 | 63.7(10.2) | 68(58%) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 14 |

| Raynauld JP; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2008; 1772833384 | 107 | 107 | 0 | 62.4(7.5) | (64%) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Longitudinal Retrospective | 15 |

| Felson DT; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2007; 1776342770 | 330 | 110 | 220 | Cases: 62.9(8.3); Controls: 61.2(8.4) | 211(63.9%) | No | No | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Case control | 12 |

| Kornaat PR; European Radiology; 2007; 17823802196 | 182 | 71 | 59(Range: 43–76) | 157(80%) | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 8 | |

| Hunter DJ; Arthritis Research & Therapy; 2007; 17958892197 | 160 | 80 | 80 | 67(9) | (46%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 11 |

| Englund M; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2007; 1805020140 | 310 | 102 | 208 | Cases: 62.9(8.3) | 211(68.1%) | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | Yes | No | Case control | 15 |

| Davies-Tuck ML; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 1809384785 | 74 | 0 | 74 | Meniscal tear: 58.8(6); No meniscal tear: 55.5(4.3) | 74(100%) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 13 |

| Hernandez-Molina G; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2008; 18163483198 | 258 | 258 | 0 | 66.6(9.2) | (42.6%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Longitudinal Prospective | 11 |

| Teichtahl AJ; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2009; 18194873199 | 99 | 99 | 0 | 63 (10) | (60%) | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 14 |

| Amin S; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 1820362986 | 265 | 265 | 67(9) | (43%) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Longitudinal Prospective | 11 | |

| Teichtahl AJ; Obesity; 2008; 18239654200 | 297 | 297 | 58(5.5) | 186 | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 14 | |

| Blumenkrantz G; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 18337129201 | 18 | 8 | 10 | Cases: 55.7(7.3); Controls: 57.6(6.2) | 18(100%) | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Case control | 12 |

| Song IH; Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases; 2009; 18375537202 | 41 | 41 | 65(6.7) | 26 | No | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Yes | Randomized controlled trial | 14 | |

| Scher C; Skeletal Radiology; 2008; 1846386567 | 65 | 65 | 0 | OA-only: 49.3 (Range: 28–75); OA&BME group: 53.5(35–82) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No | No | Longitudinal Retrospective | 10 | |

| Sharma L; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2008; 1851277787 | 153 | 153 | 0 | 66.4(11) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 11 | |

| Owman H; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2008; 18512778203 | 15 | 9 | 7 | 50(Range: 35–70) | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 10 | |

| Madan-Sharma R; Skeletal Radiology; 2008; 1856681375 | 186 | 74 | 112 | 60.2(Range: 43–76) | 150 | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 11 |

| Amin S; Journal of Rheumatology; 2008; 18597397168 | 192 | 192 | 69(9) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Cross-sectional | 10 | ||

| Pelletier JP; Osteoarthritis & Cartilage; 2008; 1867238625 | 27 | 1 | 64.1(9.6) | 14 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Other | 9 | |

| Amin S; Arthritis & Rheumatism; 2009; 19116936204 | 265 | 265 | 0 | 67(9) | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No | No | Longitudinal Prospective | 16 | |

The analysis included data from 61 manuscripts of which 1 pertains to the hip and the remainder to the knee. The mean Downs criteria score for these manuscripts was 11.5 (range 6–17). What follows below are important excerpts from this data pertaining to different aspects of predictive validity. The data is further summarized in Table IV to discretely identify the associations examined and those where a significant association was found.

Table IV.

Summary of Predictive Validity of MRI in OA

| Outcome of interest | Number of studies examining this outcome | Number of studies finding significant associations (P < .05) |

|---|---|---|

| Joint replacement | 3 studies | 3 of 3 (100%) |

| Change in symptoms | 6 studies | 5 of 6 (83%) |

| Radiographic progression | 8 studies | 5 of 8 (63%) |

| MRI progression | 19 studies | 16 of 19 (84%) |

Prediction of joint replacement

Three studies examined the predictive relation of MRI findings to joint replacement. Of these, 100% demonstrated a statistically significant association, defined as P < 0.05.

One study investigated the relation of change in quantitative cartilage volume to risk of knee replacement. For every 1% increase in the rate of tibial cartilage loss there was a 20% increase risk of undergoing a knee replacement at four years (95% CI, 10%–30%). Those in the highest tertile of tibial cartilage loss had 7.1 (1.4–36.5) higher odds of undergoing a knee replacement than those in the lowest tertile. Change in bone area also predicted risk of TKR OR 12 (95% CI 1–14)65.

Higher total cartilage defect scores (8–15) were associated with a 6.0-fold increased risk of joint replacement over 4 yr compared with those with lower scores (2–7) (95% CI 1.6, 22.3), independently of potential confounders66.

A separate smaller study investigated the relation of bone marrow lesions (assessed semi-quantitatively) to need for TKR. Subjects who had a bone marrow lesion were 8.95 times as likely to progress rapidly to a TKA when compared to subjects with no BME (P = 0.016). There was no relation of TKR with meniscal tear or cartilage loss67.

Prediction of change in symptoms

Six studies examined the predictive relation of MRI findings to change in symptoms. Of these, 83% demonstrated a statistically significant association, defined as P < 0.05.

Weak associations between worsening of symptoms of OA and increased cartilage loss: pain [r(s) = 0.28, P = 0.002], stiffness [r(s) = 0.17, P = 0.07], and deterioration in function [r(s) = 0.21, P = 0.02]20.

Small study did not find a significant relation between changes in WOMAC scores with the amount of cartilage loss and the change in BME (P > 0.05)68.

Multivariate analyses of knee pain 1 year following arthroscopic partial meniscectomy demonstrated that medial tibial cartilage damage accounting for 13% of the variability in pain scores69.

The BOKS study examined the relationship between longitudinal fluctuations in synovitis with change in pain and cartilage in knee osteoarthritis. Change in summary synovitis score was correlated with the change in pain (r = 0.21, P = 0.0003). An increase of one unit in summary synovitis score resulted in a 3.15-mm increase in VAS pain score (0–100 scale). Effusion change was not associated with pain change. Of the three locations for synovitis, changes in the infrapatellar fat pad were most strongly related to pain change24.

A nested case-control study examined if enlarging BMLs are associated with new knee pain. Case knee was defined as absence of knee pain at baseline but presence of knee pain both times at follow-up. Controls were selected randomly from among knees with absence of pain at baseline. Among case knees, 54 of 110 (49.1%) showed an increase in BML score within a compartment, whereas only 59 of 220 control knees (26.8%) showed an increase (P < 0.001 by chi-square test). A BML score increase of at least 2 units was much more common in case knees than in control knees (27.5% vs 8.6%; adjusted odds ratio 3.2, 95% CI 1.5–6.8)70.

Increases in Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) pain and patient global scores over time are associated with change in cartilage volume of the medial tibial plateau and medial femoral condyle71.

Weak association of cartilage volume loss with less knee pain. Medial cartilage volume loss and simultaneous pain change at 24 months (beta coefficient −0.45, P = 0.03) and SF-36 physical components (beta coefficient 0.22, P = 0.04)72.

Prediction of radiographic progression

Eight studies examined the predictive relation of MRI findings to radiographic progression. Of these, 63% demonstrated a statistically significant association, defined as P < 0.05.

No significant association between reduction in JSW and cartilage volume (R < 0.13). Trend toward a significant association between change in medial tibiofemoral cartilage volume and joint replacement at 4 years (OR = 9.0, P = 0.07) but not change in medial tibiofemoral JSW (OR = 1.1, P = 0.92)50.

No correlation between the cartilage volume loss changes (either by using absolute or percentage values) and the JSW changes at 24 months (global cartilage volume, r = 0.11; medial compartment cartilage volume, r = 0.19)72.

Medial femorotibial JSN after 1 year, assessed by radiography, was significantly correlated with a loss of medial tibial cartilage volume (r = 0.25, P = 0.046) and medial tibial cartilage thickness (r = 0.28, P = 0.025), over the same period73.

Higher baseline composite cartilage scores and increases in composite cartilage scores during follow-up were moderately correlated with greater joint space loss (r = 0.33, P = 0.0002 and r = 0.26, P = 0.01, respectively)74.