Abstract

The murine olfactory system consists of main and accessory systems that perform distinct and overlapping functions. The main olfactory epithelium (MOE) is primarily involved in the detection of volatile odorants, while neurons in the vomeronasal organ (VNO), part of the accessory olfactory system, are important for pheromone detection. During development, the MOE and VNO both originate from the olfactory pit, however, the mechanisms regulating development of these anatomically distinct organs from a common olfactory primordium are unknown. Here we report that two closely related zinc-finger transcription factors FEZF1 and FEZF2 regulate the identity of MOE sensory neurons and are essential for the survival of VNO neurons respectively. Fezf1 is predominantly expressed in the MOE while Fezf2 expression is restricted to the VNO. In Fezf1 deficient mice, olfactory neurons fail to mature and also express markers of functional VNO neurons. In Fezf2 deficient mice, VNO neurons degenerate prior to birth. These results identify Fezf1 and Fezf2 as important regulators of olfactory system development and sensory neuron identity.

Keywords: main olfactory epithelium, vomeronasal organ, olfactory receptor, vomeronasal receptor, cell fate

Introduction

To perceive their chemical environment, mice coordinate the functions of the main and accessory olfactory systems. The main olfactory system is composed of the main olfactory epithelium (MOE) and the main olfactory bulb, which are involved in odorant detection. Alternatively, the accessory olfactory system consists of the vomeronasal organ (VNO), the Grüneberg ganglion, the septal organ of Masera and the accessory olfactory bulb (Munger et al., 2009). The best studied of these accessory sense organs, the VNO, is primarily involved in pheromone detection (Dulac and Torello, 2003). Thus, the MOE and VNO are considered functionally and anatomically distinct organs.

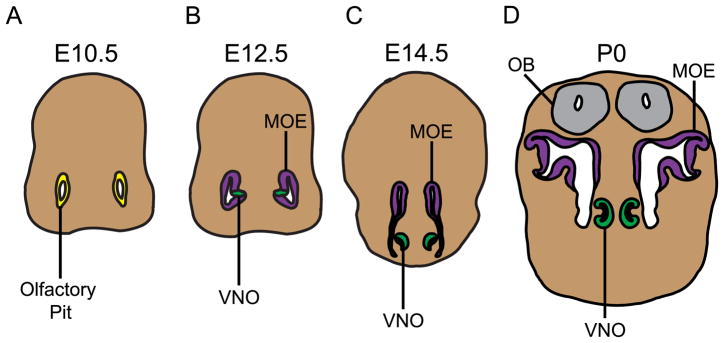

During mid-gestation the MOE and VNO both originate from the bilaterally symmetrical olfactory pits, which are invaginations of epithelial and underlying mesenchymal cells (Figure 1A) (Balmer and LaMantia, 2005). At E9.5 the olfactory pits first develop as a thickening of the frontal epithelial cell layer of the developing embryo known as the olfactory placode. The olfactory placode begins to show signs of neural differentiation such as β-tubulin and NCAM expression, and by E10.5 has undergone an initial invagination to produce the two olfactory pits (LaMantia et al., 2000) (Figure 1A). By E12.5 the olfactory pits undergo a second invagination in the ventromedial wall that produces the VNO (Figure 1B). The developing VNO separates from the olfactory pit and becomes a spatially distinct organ from the MOE by E14.5 (Figure 1C–D) (Balmer and LaMantia, 2005).

Figure 1.

A diagram depicting the developmental origins of the main olfactory epithelium (MOE) and vomeronasal organ (VNO) from the olfactory pit. All schematics shown depict a coronal orientation. (A) At E10.5 the olfactory pit (shown in yellow) is morphologically discernible but does not show any distinction between the regions that will give rise to the MOE and VNO. (B) By E12.5 the pit has undergone an initial invagination, distinguishing the dorsal region that will give rise to the MOE (purple) from the ventromedial region that will become the VNO (green). (C) By E14.5 the VNO has separated from the pit and become anatomically distinct. (D) This spatial and molecular distinction is clear at birth (P0), with both the MOE and VNO projecting axons to innervate the olfactory bulb (OB) (grey). Diagrams are not drawn to scale.

The mature MOE and VNO consist of a sensory neuron layer and an apical layer of supporting cells (Kawauchi et al., 2004). The MOE also contains a basal layer of progenitor cells (Beites et al., 2005). Tremendous progress has been made toward determining the signaling events in sensory neurons of the MOE and VNO (Mombaerts, 2004). The mouse genome encodes about 1,000 G protein-coupled olfactory receptor genes (ORs) and each sensory neuron of the MOE (OSN) expresses only one of these ORs. Binding of odorant molecules to an OR activates the OSN-specific G protein Gαolf, which then activates adenylate cyclase III (Jones and Reed, 1989). The resulting increase in cAMP levels leads to the opening of olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channels and the propagation of an action potential (Liman and Buck, 1994). In addition to the ORs, the mouse genome encodes two classes of G protein-coupled pheromone receptors: V1Rs and V2Rs. Sensory neurons in the apical zone of the VNO (VSNs) express V1Rs and the G protein subunit Gαi2, while VSNs in the basal zone express V2Rs and Gαo. Binding of pheromone molecules to V1Rs or V2Rs likely leads to the activation of the VNO-specific cation channel Trpc2. Axons from OSNs innervate the main olfactory bulb (MOB) while axons from the VSNs project to the accessory olfacotry bulb (AOB) (Mombaerts, 2004).

Significant advances have been achieved in understanding transcriptional control of OSN development. Mash1 is an important proneural gene in olfactory neurogenesis. It is expressed in the progenitor cells of MOE but not in differentiated OSNs (Cau et al., 1997; Gordon et al., 1995). In Mash1−/− mice, the number of mitotic progenitors and neurons are reduced in the MOE, and expression of the sustentacular cell marker Kitl is dramatically increased (Cau et al., 2002; Cau et al., 1997; Guillemot et al., 1993; Murray et al., 2003), indicating that Mash1 is critical for neuronal determination in the MOE. Two transcription factors, Hes1 and Wt1 (+KTS) have been shown to affect the expression of Mash1 (Cau et al., 2002; Cau et al., 2000; Wagner et al., 2005), and mice carrying mutations in these genes show abnormal MOE neurogenesis (Cau et al., 2002; Cau et al., 2000; Wagner et al., 2005). Many transcription factors, including Ngn1 (Cau et al., 2002; Cau et al., 1997) and Lhx2 (Cau et al., 2002; Hirota and Mombaerts, 2004; Kolterud et al., 2004) act downstream of Mash1 and are important for OSN differentiation. Additional transcription factors, such as members of O/E family (Wang et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2004; Wang et al., 1997), Mecp2 (Matarazzo et al., 2004; Ronnett et al., 2003), Dlx5 (Levi et al., 2003; Long et al., 2003), and KLF7 (Laub et al., 2001; Luo et al., 1995; Tanaka et al., 2002), function further downstream in OE development and regulate OSN maturation and axonal projections to the OB. Although these studies have focused on MOE and OSN development, many of these transcription factors are also expressed in the VNO, suggesting that similar mechanisms may regulate VSN development. Despite this progress, the mechanisms regulating the early cell fate decisions that generate the MOE and VNO, two distinct organs that develop from a common primordium, are not well understood.

Fez family zinc-finger proteins 1 and 2 (FEZF1 and FEZF2) are two closely related transcription factors expressed early during mouse development that are important for brain development and cell identity. Fezf2 is required for proper fate specification of layer 5 subcortical projection neurons in the cerebral cortex (Chen et al., 2005a; Chen et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2005b; Molyneaux et al., 2005), while Fezf1 is essential for proper development of the OB and MOE (Hirata et al., 2006b; Watanabe et al., 2009). Furthermore, both Fezf1 and Fezf2 are required for regulation of forebrain size and patterning during early development (Hirata et al., 2006a; Shimizu et al., 2010). Here we report the functions of Fezf1 and Fezf2 in establishing MOE neuronal identity and VNO development, respectively. We found that Fezf1 and Fezf2 show distinct expression patterns in the developing olfactory system. Fezf1 is expressed strongly in the MOE and weakly in the VNO, while Fezf2 is specifically and highly expressed in the VNO. Analysis of Fezf1−/− and Fezf2−/− mice indicates these genes are necessary for proper cell identity of olfactory sensory neurons (OSNs) and maintenance of the VNO, respectively. In Fezf1 deficient mice, OSNs fail to mature and express VNO-enriched neuronal markers. In contrast, Fezf2 mutant animals lack a VNO at birth. These results identify Fezf1 and Fezf2 as important regulators of olfactory system development and sensory neuron identity.

Materials and Methods

Generation of Fezf1−/− and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice

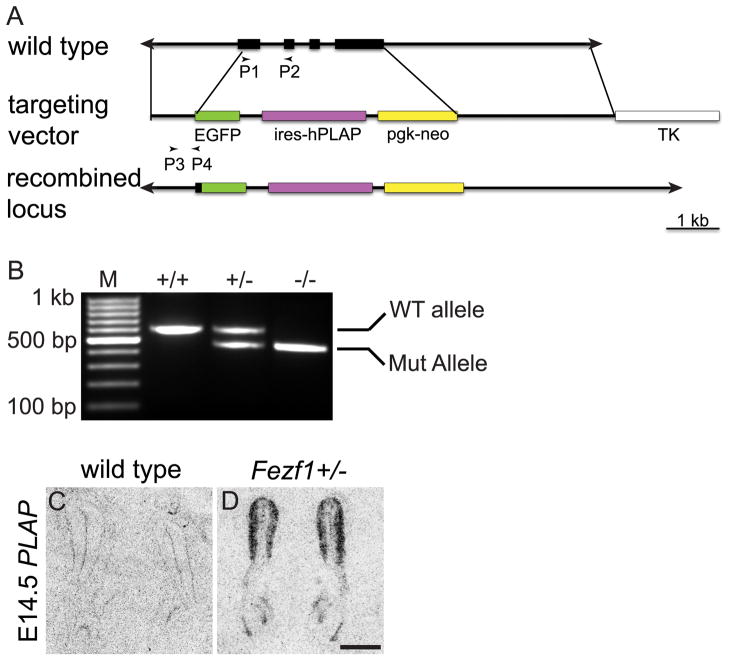

A targeting vector was designed to replace the Fezf1 coding region with a cassette containing enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) followed by an internal ribosome entry site (IRES)-human placental alkaline phosphatase (hPLAP) and PGK-neo (Figure 2A). It contains a 3 kb homologous sequence upstream of and including the sequence encoding the first 10 amino acids of FEZF1, a 5.2 kb EGFP-IRES-hPLAP cassette, a 2 kb PGK-neo cassette, a 4.3 kb homologous sequence downstream of the Fezf1 gene, and the RSV-TK negative selection cassette. The junction of Fezf1 and EGFP was sequenced to ensure that no mutations were generated during cloning and that the EGFP ORF was in frame. The linearized knockout construct was electroporated into E14a ES cells, which were subjected to both positive and negative selections. Correctly-targeted ES clones were identified by Southern hybridization. Two clones were used to generate chimeric mice by blastocyst injection. After germline transmission of the mutant allele, heterozygous Fezf1+/− mice were mated to β-actin-cre CD1 mice to excise the floxed pgk-neo selection cassette. Fezf1+/− mice were then mated to generate Fezf1−/− mice. Proper expression of the targeted allele was confirmed by in situ hybridization to detect hPLAP mRNA (Figure 2C, D).

Figure 2.

Fezf1 knockout strategy. The endogenous Fezf1 locus was replaced with a cassette containing EGFP-IRES-hPLAP (A) and transmission of the targeted allele was confirmed by PCR using primers P1 and P2 (for wild type allele), P3 and P4 (for mutant allele) (B). Appropriate expression of the targeted Fezf1 allele was confirmed by radioactive in situ hybridization to detect PLAP expression in Fezf1+/− (D), but not in wild type mice (C). The scale bar in D is 100 μm.

Generation of Fezf2+/− mice has been described previously (Chen et al., 2005a). Fezf1+/− mice were bred with Fezf2+/− mice to obtain Fezf1+/−; Fezf2+/− compound heterozygotes. Breeding Fezf1+/−; Fezf2+/− mice with each other generated animals carrying various combinations of Fezf1 and Fezf2 mutant alleles.

Genotyping of Fezf1 alleles was accomplished by PCR using two sets of primers. The wild type allele was genotyped using p1 (ATGGACAGTAGCTGCCTCAACGCGACC) and p2 (ATGTTCACGCTCGCAGCCGGGTGGCAC), with an expected PCR product of 589 bp (Figure 2A, B). The mutant Fezf1 allele was genotyped using p3 (GGGGAAGCTCTCTCACCAATG) and p4 (GGGGAAGCTCTCTCACCAATG), yielding the expected product of 460 bp (Figure 2A, B). The PCR conditions were 94°C for 2 min, followed by 35 cycles of 94°C for 30 sec, 64°C for 1 min and 72°C for 1 min. Genotyping of Fezf2 alleles was reported previously (Chen et al., 2005a).

The day of vaginal plug detection was designated as embryonic day 0.5 (E0.5). The day of birth was designated as postnatal day 0 (P0). Experiments were carried out in accordance with protocols approved by the IACUC at the University of California, Santa Cruz and were performed in accordance with institutional and federal guidelines.

Immunohistochemistry

Tissue samples were fixed overnight in 4% paraformaldehyde at 4°C and transferred to 30% sucrose overnight at 4°C. The following morning they were frozen in Tissue-Tek O.C.T. compound (Sakura Finetek). 20μm tissue sections were collected onto Superfrost slides (Fisher Scientific) (Figures 2, 3, 4). Alternatively, for Figure 10, 50 μm floating sections were processed for immunohistochemistry. Primary antibodies used are described in Table 1. Primary antibodies were detected using AlexaFluor-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen, 1:1000). Nuclei in Figure 2 were visualized using SYTOX orange (Invitrogen, 1:100,000).

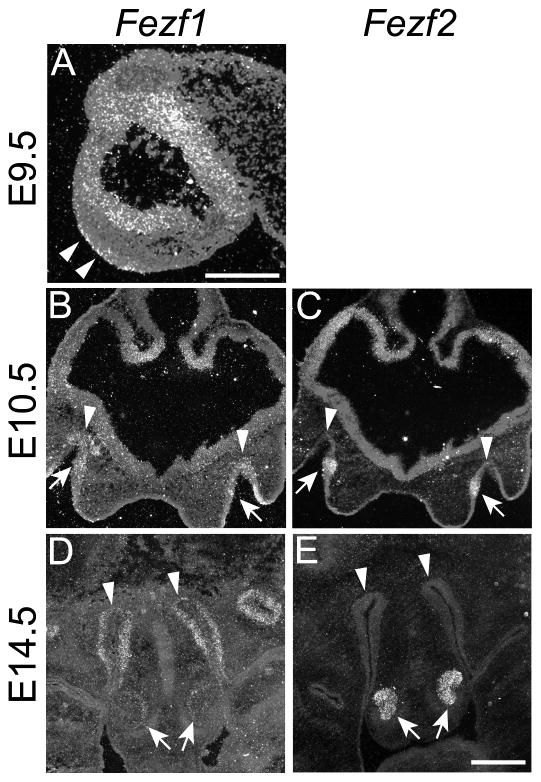

Figure 3.

Expression of Fezf1 and Fezf2 transcripts during olfactory system development. Radioactive in situ hybridization was used to detect Fezf1 (A, B, and D) or Fezf2 (C, and E) expression. At E9.5 Fezf1 was detected in the olfactory placode (arrowheads in A). At E10.5 it is detected throughout the newly formed olfactory pits (arrowheads in B). Fezf1 remains strongly expressed in the MOE (arrowheads in D) and weakly in the VNO (arrows in D) at E14.5 and later stages (D, and data not shown). Alternatively, Fezf2 is specifically expressed in the VNO throughout olfactory system development (arrows in C and E). A, sagittal section; B–E, coronal sections. The scale bar in A is 25 μm and in E is 100 μm.

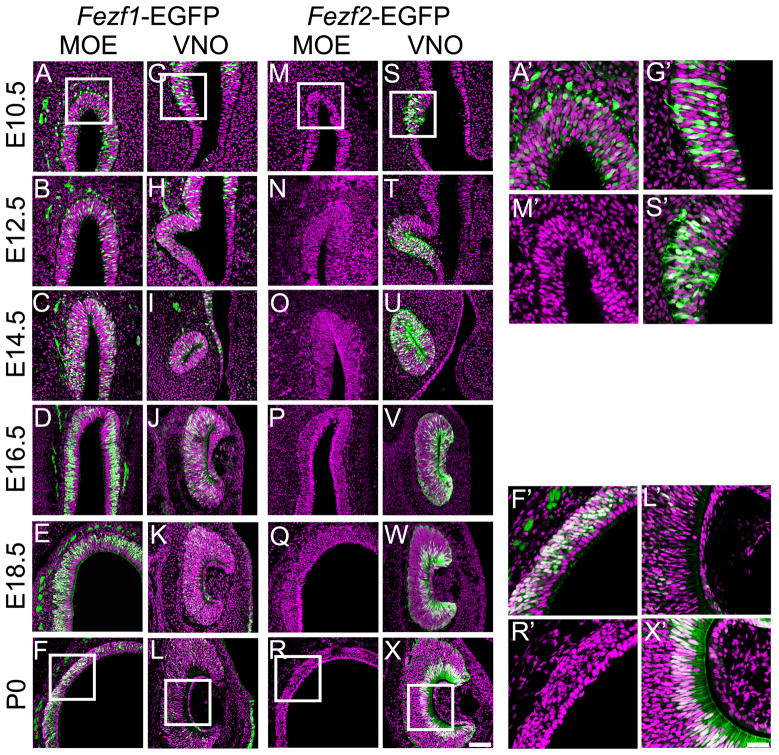

Figure 4.

Expression patterns of Fezf1 and Fezf2 during development of the olfactory system detected by EGFP reporter expression. GFP immunohistochemistry was used to visualize cells expressing either Fezf1-EGFP (A–L, A′, F′, G′, L′) or Fezf2-EGFP (M–X, M′, R′, S′, X′). Nuclei were visualized using SYTOX orange. At E10.5 and E12.5, Fezf1-EGFP is expressed throughout the future MOE and VNO (A, B, G, H, A′, and G′). After E14.5 Fezf1-EGFP expression starts to decrease in the VNO and becomes restricted to progenitor and neuronal cell layers of the MOE (D–F, J–L, F′, and L′). This transition is complete by E18.5 and persists postnatally (E, F, K, L, F′, and L′). In contrast to the Fezf1-EGFP expression pattern, Fezf2-EGFP expression is restricted to the VNO throughout olfactory system development (M–X, M′, S′, R′, and X′). At E10.5, when the VNO is first starting to differentiate from the olfactory pit, Fezf2-EGFP is strongly expressed throughout cells in the ventromedial anlage that will give rise to the VNO (S, S′). Beginning at E14.5, Fezf2-EGFP expression undergoes a dynamic transition and becomes restricted to the sustentacular cell layer of the VNO (O–R; U–X, R′, X′). This expression pattern of Fezf2-EGFP is maintained postnatally (R, X, R′, X′). For all images, EGFP expression is shown in green and SYTOX orange staining is in purple. Images in A′, F′, G′, L′, M′, R′, S′ and X′ represent the enlarged regions shown in the white boxes in panels A, F, G, L, M, R, S and X. The scale bar in X is 75 μm and in X′ is 30 μm.

Figure 10.

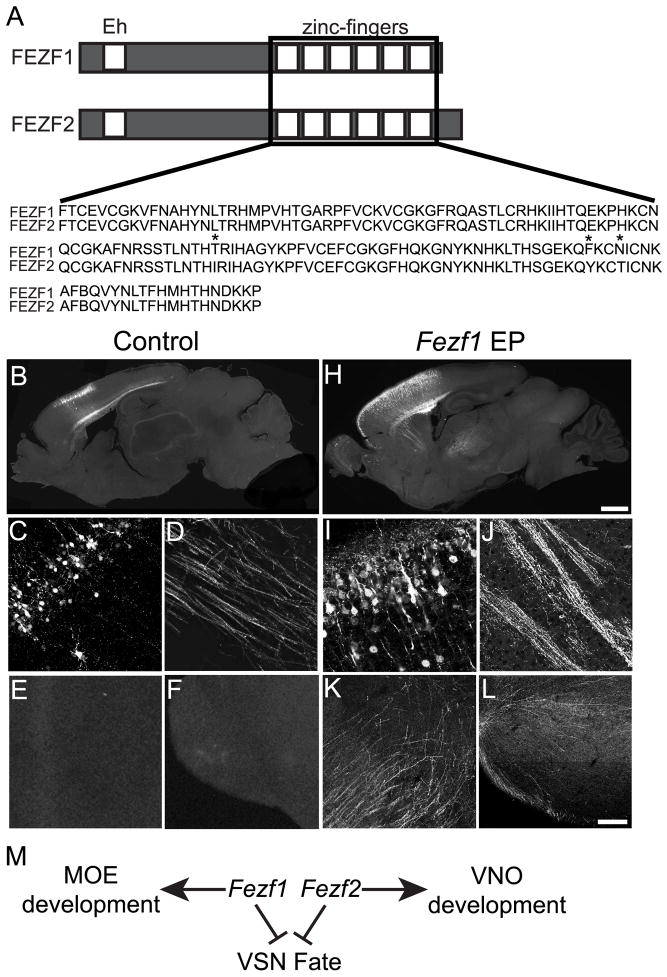

Fezf1 and Fezf2 can function interchangeably during cell fate specification in vivo. (A) A schematic presentation of identifiable FEZF1 and FEZF2 protein domains showing their N-terminal engrailed homology domain (Eh) and C-terminal C2H2 zinc-finger motifs. An alignment of the zinc-finger motifs shows only three amino acid differences (*), corresponding to 97% identity between the two proteins. (B–L) Misexpression of Fezf1 in corticocortical projection neurons of the cerebral cortex is sufficient to redirect their axons subcortically, similar to previously reported results for Fezf2 misexpression (Chen et al., 2008). When Fezf1 and EGFP were electroporated into layer 2/3 neurons in utero (H–L) their axons are redirected to the striatum (J), thalamus (K) and pons (L). No GFP+ axons were detected in these brain regions when only EGFP was misexpressed (B–F). Our model predicts that Fezf1 promotes MOE development and Fezf2 promotes VNO development by preventing progenitors and sensory neurons of the MOE and progenitors and supporting cells of the VNO from assuming a VNO sensory neuron identity (M). The diagram in A is not drawn to scale. The scale bar in H is 1 mm and in L is 75 μm.

Table 1.

List of antibodies used for this study

| Antibody | Host | Source (Cat. No.) | Dilution | Immunogen |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cleaved Caspase-3 | Rabbit (P) | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA (9661) | 1:200 | synthetic peptide (KLH- coupled) CRGTELDCGIETD adjacent to D175 in human caspase-3 |

| GFP | Chicken (P) | Aves Labs, Tigard, OR (GFP-1020) | 1:1000 | recombinant GFP protein emulsified in Freund’s adjuvant |

| Gαs/olf | Rabbit (P) | Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA (sc-383) | 1:25 | c-terminal peptide between amino acids 377–394 of rat |

| L1 | Rat (M) | Chemicon, Temecula, CA (MAB5272, clone 324) | 1:500 | glycoprotein fraction from the cerebellum of C57BL/6J mice |

| NCAM | Rat (M) | Chemicon, Temecula, CA (MAB310) | 1:500 | glycoprotein fraction from neonatal mouse brain |

| OMP | Goat (P) | Wako, Richmond, VA (544-10001) | 1:1000 | rodent protein |

| PHH3 | Mouse (M) | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA (9706) | 1:100 | synthetic phospho-peptide (KLH coupled) ATKQTARKSTGGKA surrounding S10 of human histone H3 |

P, polyclonal; M, monoclonal

Immunohistochemistry was performed as follows. Tissue sections were washed three times for five minutes each in PBS (pH 7.4) and placed into blocking solution (10% horse serum, 0.3% Triton X-100 in PBS) for one hour at room temperature. Primary antibodies were added at the appropriate dilutions (Table 1) and incubated overnight at 4°C. The following day sections were washed three times in PBS and incubated with the secondary antibodies for two hours at room temperature. Sections were then washed three times in PBS and cover-slipped with Fluoromount-G (Southern Biotech).

Antibody Characterization

The antibodies used in this study are listed in Table 1. Characterization and controls for each primary antibody used are described below. The anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibody detects the large fragment (17/19 kDa) of caspase-3 resulting from cleavage adjacent to D175 in western blot analysis of extracts from HeLa, NIH/3T3 and C6 cells. It does not recognize full-length caspase-3 or other cleaved caspases (manufacturer’s technical information). Immunostaining using this antibody detects apoptotic cells both in culture and in tissue sections. The specificity of the staining has been confirmed by the use of blocking peptide in both western analysis and in immunohistochemistry. Antibody preincubated with control peptide stained cells in mouse embryonic tissue or human tonsil tissue sections, but antibody preincubated with cleaved caspase-3 (Asp175) blocking peptide (Cell signaling, #1050) completely failed to stain mouse or human tissue sections. In addition, western blot analysis of cell extracts from Jukrat cells treated with 0.25 mg/ml cytochrome C (to induce apoptosis) using cleaved caspases-3 antibody showed specific bands at 17 and 19 kDa. Western blot analysis of the same cell extract using cleaved caspase-3 antibody preincubated with the blocking peptide (1/100) prevented the antibody from recognizing the 17/19 kDa bands (manufacturer’s technical information).

The anti-GFP antibody labels neurons only in mice carrying an EGFP targeted allele or transgene and not in wild type animals. This staining pattern recapitulates the intrinsic fluorescence of the EGFP (Eckler and Chen, unpublished observation).

The anti-Gαs/olf antibody was developed against a rat C-terminal peptide (aa 377–394) (Daniel Crews, Santa Cruz Biotech, personal communication). Western blotting of T98G or HeLa whole cell lysates recognizes 3 bands (52 kDa, 45 kDa, 39 kDa) corresponding to the long and short forms of Gαs and Gαolf (manufacturer’s technical information). In our study, this antibody labeled the cilia of olfactory neurons, where olfactory receptors bind to odorant molecules and initiate cell signaling events. This staining pattern is consistent with the mRNA expression pattern of Gαs/olf, which was detected in the olfactory neurons of the MOE by in situ hybridization (Eckler and Chen, unpublished result). Our in situ hybridization results showed that compared to wild type P0 mice, the expression level of Gαs/olf mRNA was decreased in the MOE of Fezf1−/− P0 mice. The reduced staining with anti-Gαs/olf antibody in the MOE of Fezf1−/− mice confirmed the specificity of this antibody.

The anti-L1 rat monoclonal antibody was generated by immunizing rats with a glycoprotein fraction from P8–P9 mouse cerebellum. The antibody reacts with both mouse and rat tissues in immunohistochemistry. In western blot analysis, it recognizes the 220–240 kDa mouse L1 protein (manufacturer’s technical information). The specificity of this antibody has been confirmed using L1 knockout mice. In lysates from mutant mice, western blot analysis showed a complete absence of the normal L1 protein. In wild type mice, L1 staining was detected in the ventral-lateral columns of spinal cord at E11.5 and in the dorsal root ganglion axons. In the L1 mutant mice, L1 staining was not detected (Cohen et al., 1998). In the olfactory system and in mouse brains, this antibody labeled the cell body and projections of neurons.

Specificity of the anti-NCAM antibody has been demonstrated by the use of NCAM knockout animals. In NCAM−/− mice no staining was observed with this antibody (Schellinck et al., 2004). We observed similar staining patterns to those previously described (Inaki et al., 2002; Schellinck et al., 2004; Taniguchi et al., 2003), with strong labeling of neuronal cell bodies and projections.

The anti-OMP antibody strongly labels mature sensory neurons throughout the olfactory system (Marcucci et al., 2009; Watanabe et al., 2009). This antibody recognizes a single band of 19 kD by western blot using mouse brain extract (Baker et al., 1989). In tissue sections we observed strong labeling of cell bodies and axons of both OSNs and VSNs. This labeling pattern is consistent with the mRNA expression pattern of OMP gene detected by in situ hybridization (Eckler and Chen, unpublished result).

The anti-phosphorylated histone H3 (ser10) antibody detects endogenous levels of histone H3 only when phosphorylated at serine 10. This antibody does not cross-react with other phosphorylated histones or acetylated histone H3. The specificity of this antibody was confirmed using several assays. Western blot analysis of whole cell lysates from NIH/3T3 cells treated with serum plus calyculin A to induce histone H3 phosphorylation recognized a 16.5 kD band, which was not observed in untreated samples. Flow cytometric analysis of pacilitaxel-treated THP1 cells using this antibody versus Propidium Iodide showed that the cells stained by this antibody contained higher DNA content, corresponding to cells that passed S phase of the cell cycle. Co-staining cultured NIH/3T3 cells with the anti-phosphorylated histone H3 antibody and with a tubulin antibody (to label microtubule cytoskeleton and mitotic spindles) showed that only dividing cells were stained by the anti-phosphorylated histone H3 antibody, and that nonmitotic cells were unstained. Immunohistochemical analysis of paraffin-embedded human carcinoma tissues using this anti-phosphorylated histone H3 antibody showed specific staining, but the staining was abolished when the tissue was treated with phosphatase, or when the antibody was preincubated with phosphohistone H3 (ser10) blocking peptide (#1000, Cell Signaling) (manufacturer’s technical information). In our hands, this antibody strongly labeled cells in the ventricular and subventricular zone in developing mouse brains that were undergoing mitosis (Betancourt and Chen, unpublished observation).

PLAP staining

PLAP activity was detected with AP staining buffer (0.1 mg/ml 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate, 1 mg/ml nitroblue tetrazolium in 100 mM Tris-HCl pH9.5, 100 mM NaCl) as previously described (Chen et al., 2008).

In situ hybridization

In situ hybridization using 35S-labeled probes was performed as previously described (Chen et al., 2005a). Fresh-frozen olfactory tissue was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 minutes at room temperature and then dehydrated with ethanol. Slides were treated with proteinase K for 30 minutes at room temperature, acetylated for 10 minutes, and then washed with 2X SSC. 35S-labeled cRNA probes were hybridized to sections overnight at 65°C. The following day slides were washed with SSC and subjected to RNase A digestion for 30 minutes at 37°C. Slides were then dehydrated and dipped in Kodak NTB2 emulsion 1:1 with distilled water. Kodak D19 and Rapid Fix solutions were used to develop the slides and cresyl violet was used as a counter stain.

Non-radioactive in situ hybridization was performed essentially as described (Schaeren-Wiemers and Gerfin-Moser, 1993). Briefly, digoxigenin-labeled cRNA probes were synthesized for the genes of interest. Probes were hybridized to sections of fresh-frozen olfactory tissue overnight and visualized by the addition of NBT/BCIP substrate at room temperature.

Probes used in this study are described in Table 2. In addition to their primary targets, the following probes likely cross react with additional mRNAs based on their high degree of homology. The OR mix probe is 94% homologous to nucleotides 214–895 of Olfr1198 (NM_207567.1). The Taar mix probe is 98% homologous to nucleotides 3–863 of Taar8b (NM_001010837), 99% homologous to nucleotides 42–902 of Taar8c (NM_001010840), and 81% homologous to nucleotides 30–860 of Taar6 (NM_001010828.1). The V1R mix probe is 88% homologous to nucleotides 132–858 of V1rb1 (NM_053225.1), 90% homologous to nucleotides 132–858 of V1rb2 (NM_011911.1), 90% homologous to nucleotides 228–956 of V1rb3 (NM_053226.2), 91% homologous to nucleotides 130–858 of V1rb4 (NM_053227.2), 88% homologous to nucleotides 130–855 of V1rb8 (NM_053229.1), and 91% homologous to nucleotides 130–858 V1rb9 (NM_053230.1). The V2R mix probe is 99% homologous to nucleotides 1500–2405 of Vmn2r2 (NM_001104592.1), 93% homologous to nucleotides 1698–2591 of Vmn2r3 (NM_001104614.1), 94% homologous to nucleotides 1512–2405 of Vmn2r4 (NM_001104615.1), 96% homologous to nucleotides 1500–2405 of Vmn2r5 (NM_001104618.1), 93% homologous to nucleotides 1512–2405 of Vmn2r6 (NM_001104619.1), and 93% homologous to nucleotides 1513–2405 of Vmn2r7 (NM_175674.3).

Table 2.

List of in situ probes used for this study

| Probe (type) | Target | Preperation |

|---|---|---|

| Cnga2 (S) | nucleotides 17374–17925 of mouse Cnga2 (* NC-_000086) | primers (5′-GCGCGCAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAATAGGGAGATCCTGATGAAGGAA-3′) and (5′-GCGCGCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTCTAGTCCCAGAAAAGCCTCAG-3′), incorporating T3 or T7 promoter sequences respectively, were used to generate a temple for in vitro transcription with T7 polymerase |

| Fezf1 (S) | nucleotides 289–828 of mouse Fezf1 (* NC_000072) | primers (5′GCGCGCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCATGGACAGTAGCTGCCTCAACGCGACCA-3′) and (5′-GCGCGCAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAACGGGTGGATGTTCACGCTCGC-3′), incorporating T7 or T3 promoter sequences respectively, were used to generate a temple for in vitro transcription with T3 polymerase |

| Fezf2 (S) | nucleotides 644–1374 of mouse Fezf2 (* NC_000080) | primers (5′GCGCGCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCATGGCCAGCTCAGCTTCCCTGGAGACCATGG-3′) and (5′GCGCGCAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAATTCTCCTTCAGCACCTGCTCCA-3′), incorporating T7 or T3 promoter sequences respectively, were used to generate a temple for in vitro transcription with T3 polymerase |

| $OR mix (D) | nucleotides 212–895 of mouse Olfr1208 (* NC_000068.6) | the PCR product from primers (5′-CTTCCACAGTAGCCCCAAAA-3′) and (5′-ACACCTTCCTCATGGCATTC-3′) was cloned into pGEM-T (Promega), linerizied with Nco I, and transcribed with SP6 polymerase |

| $TAAR mix (D) | nucleotides 3–863 of mouse Taar8a (* AC_000032.1) | the PCR product from primers (5′-GACCAGCAACTTTTCCCAAC-3′) and (5′-ATGAAGCCCATGAAAGCATC-3′) was cloned into pGEM-T (Promega), linerizied with Nco I, and transcribed with SP6 polymerase |

| Trpc2 (S) | nucleotides 7985–8594 of mouse Trpc2 (* NC_000073) | primers (5′GCGCGCAATTAACCCTCACTAAAGGGAACAGCCCAACTGGACTGAGATTGTAACAAA-3′) and (5′-GCGCGCGTAATACGACTCACTATAGGGCTGCCTCGGTAGGTGTTGATTCGGGATAGTG -3′), incorporating T3 or T7 promoter sequences respectively, were used to generate a temple for in vitro transcription with T7 polymerase |

| SV1R mix (D) | nucleotides 130–858 of mouse V1rb7 (* NC- _000072.5) | the PCR product from primers (5′-AGGCCTAAGCCCATTGATCT-3′) and (5′-AGGGTTGACTGTGGCATAGC-3′) was cloned into pGEM-T (Promega), linerizied with Not I, and transcribed with T7 polymerase |

| $V2R mix (D) | nucleotides 22833–23738 of mouse Vmn2r1 (* NC- _000069) | the PCR product from primers (5′-ACCAGGACAGAGGGAATGTG-3′) and (5′-TCAACAGTGGGGACTCTTCC-3′) was cloned into pGEM-T (Promega), linerizied with Nco I, and transcribed with SP6 polymerase |

D, digoxigenin (DIG)-labeled probe; S, 35S-labeled probe;

GenBank accession number,

See materials and methods for additional targets

Microscopy

Confocal images were captured on a Leica TCS SP5 confocal microscope. Bright and dark field images were captured on an Olympus BX51 microscope using a Q Imaging Retiga EXj camera. Images were processed using Adobe Photoshop CS4 to adjust brightness and contrast.

Cell death and proliferation analysis

E12.5 tissue sections were processed for immunohistochemistry with mouse anti-phosphorylated histone H3 and rabbit anti-cleaved caspase-3 antibodies. Total numbers of immunoreactive cells were counted on alternating 20 μm tissue sections for Fezf2+/− and Fezf2−/− VNOs. Total phosphorylated histone H3+ and cleaved caspase-3+ cells were averaged for each genotype and the standard error of mean (SEM) calculated. P-values were generated using a Student’s t-test and statistical significance was assigned to p-values of ≤0.05.

Isolation of Fezf1-EGFP+ cells by FACS

The main olfactory epithelium from E18.5 Fezf1+/− or Fezf1−/− animals was dissected in cold Neurobasal (NB) solution (Invitrogen) which had been equilibrated overnight at 37°C in a tissue culture incubator and then placed on ice. Dissections were performed using a fluorescence dissecting microscope to ensure that VNO tissues were not harvested. Tissue from mice of identical genotypes from the same litter were pooled and dissociated by incubation in a papain solution (Worthington) for 30 minutes in a 32°C water bath. Enzymatic activity was quenched by washing with trypsin inhibitor and BSA, and tissues were subjected to gentle trituration. Dissociated cells were resuspended in cold PBS with 2% BSA and filtered through a 100 μm filter. Fezf1-EGFP+ cells were isolated by FACS on a BD Biosciences Aria cell sorter. Propidium iodide staining was used to exclude dead cells.

Microarray analysis

Isolated E18.5 Fezf1-GFP+ cells were immediately processed for total RNA isolation using an RNeasy Micro Kit (Qiagen). RNA samples from Fezf1+/− and Fezf1−/− were reverse transcribed, labeled and hybridized to Affymetrix Mouse Gene 1.0 ST Arrays. Microarray experiments were performed at the Stanford Protein and Nucleic Acid (PAN) facility. Expression signals were normalized and the gene list was generated using the Partek Genomics Suite. Briefly, signal intensities for triplicate Fezf1+/− or Fezf1−/− samples were combined into a single expression score and converted to log2 scale. Pairwise analysis was performed and transcript level changes with a fold enrichment of 1.75 or greater and an ANOVA-generated p-value of 0.05 or less were considered significant. All microarray data have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database at NCBI (Accession GSE26064).

In utero electroporation

EGFP or Fezf1 cDNA was cloned into the pCMV expression vector. EGFP or EGFP plus Fezf1 plasmids were electroporated into the cerebral cortex of E15.5 CD-1 embryos as described (Chen et al., 2008). Animals were allowed to develop until P5 and axons were visualized by staining with EGFP antibodies.

Results

Fezf1 and Fezf2 show distinct expression patterns during olfactory development

To investigate the expression patterns of Fezf1 and Fezf2 in the olfactory system we performed in situ hybridization using cRNA probes. Fezf1 expression was first detected in the olfactory placode at E9.5 (Figure 3A). At E10.5, Fezf1 mRNA was detected in the invaginating olfactory pit and expression continued postnatally in the olfactory system, with higher expression in the MOE and lower expression in the VNO (Figure 3B, D, and data not shown). Fezf2 mRNA was first detected in the olfactory pit at E10.5 and was localized to the ventromedial region from which the future VNO is derived (Figure 3C). After the VNO separated from the olfactory pit, Fezf2 mRNA was detected exclusively in the VNO and this expression pattern was maintained until postnatal stages (Figure 3E, and data not shown).

The in situ hybridization data demonstrated that Fezf1 and Fezf2 preferentially demarcate two distinct parts of the olfactory system: MOE and VNO. To confirm the in situ hybridization results and further investigate the expression of Fezf1 and Fezf2 at the cellular level, we used two different reporter mouse lines. A Fezf1+/− strain generated in our laboratory that contains both EGFP and PLAP coding sequences under the control of the endogenous Fezf1 promoter (Figure 2A) was used to investigate Fezf1 expression. In the Fezf2 mutant allele generated previously (Chen et al., 2005a; Chen et al., 2008), even though an EGFP-ires-PLAP cassette was used to replace the genomic region encoding the Fezf2 open reading frame, EGFP protein was not detected in the mice carrying the mutant allele. Thus, to examine Fezf2 expression at a cellular level, instead of using the PLAP marker in the Fezf2 mutant allele, we utilized a Fezf2-EGFP transgenic mouse line carrying an EGFP marker under the control of the Fezf2 promoter, which was produced by the GENSAT project using a modified bacterial artificial chromosome (Gong et al., 2003). Consistent with the in situ hybridization results, at E10.5 and E12.5, Fezf1-EGFP was strongly expressed in cells across the full extent of the olfactory epithelium including the region that gives rise to the VNO (Figure 4A, B, and A′ for MOE, G, H and G′ for VNO). As development proceeded, Fezf1-EGFP expression remained high in the MOE (Figure 4C–F) and decreased in the VNO (Figure 4I–L). After E14.5, Fezf1-EGFP expression within the MOE became restricted to OSNs and the basal progenitor cell layer in the MOE and was excluded from the supporting cell layer (Figure 4D–F, and F′). Fezf1-EGFP expression in VNO decreased (Figure 4J–L), and was detected in very few neurons in the VNO at P0 (Figure 4L and L′).

In contrast to Fezf1-EGFP, expression of Fezf2-EGFP was restricted to the VNO. At E10.5, when VNO morphogenesis is first discernible as a local thickening of the neural epithelium in the ventromedial region of the olfactory pit, high Fezf2-EGFP expression was detected in the region that will become the VNO (Figure 4S, and S′). To our knowledge this identifies Fezf2 as the earliest marker distinguishing the region of the olfactory pit that gives rise to the VNO from the rest of the olfactory pit. Fezf2-EGFP expression persisted in the VNO during its separation from the MOE (Figure 4T and U). Prior to E14.5 Fezf2-EGFP was expressed at high levels in most cells of the developing VNO (Figure 4S, T, S′). However, after E14.5 Fezf2-EGFP expression became restricted to the apical sustentacular cell layer of the VNO (Figure 4V–X, X′). This dynamic transition was complete by E18.5 and persisted until postnatal stages (Figure 4X, X′ and data not shown). No Fezf2-EGFP expression was detected in cells of the MOE at any age (Figure 4M–R, M′, and R′). Taken together, the in situ hybridization data and cell labeling with Fezf1-EGFP and Fezf2-EGFP markers demonstrate that expression of Fezf1 and Fezf2 is largely mutually exclusive; Fezf1 is preferentially expressed in the MOE and Fezf2 is exclusively expressed in the VNO during their development. Moreover, after E14.5 Fezf1 and Fezf2 become restricted to progenitors and neurons of the MOE and sustentacular cells of the VNO, respectively.

The mechanisms regulating segregation of the MOE and VNO from a common olfactory primordium remains unknown. Because Fezf2 plays an essential role in specifying neuronal identity in the developing cerebral cortex, preferential expression of Fezf1 in the MOE and exclusive expression of Fezf2 in the VNO suggested that these two genes are involved in specifying MOE and VNO cell identities. We tested this possibility by analyzing development of the olfactory system in Fezf1−/−, Fezf2−/−, and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice.

Incomplete maturation of the MOE in Fezf1−/− and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice

If Fezf1 is required for specification of MOE identity, Fezf1−/− mice should exhibit abnormal olfactory system development. Indeed, defects in the MOE of Fezf1−/− mice have been described previously (Hirata et al., 2006b; Watanabe et al., 2009). Consistent with published data, when we examined the olfactory axon projections in Fezf1−/− mice using the PLAP marker which was knocked into the Fezf1 mutant allele, we found that OSNs were present in Fezf1−/− mice but their axonal projections failed to reach the olfactory bulb and instead formed a fasciculated bundle (compare panels 5A, B). This defect was not observed in Fezf2−/− animals (Figure 5C), and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice showed no exacerbation of the OSN axonal defects in the Fezf1−/− animals (Figure 5B, D).

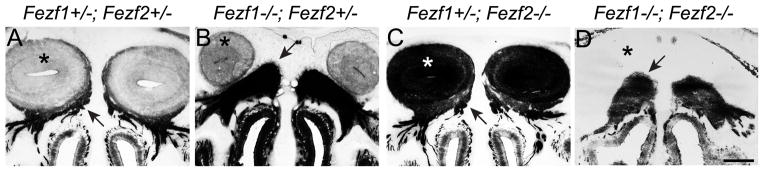

Figure 5.

Fezf1 is required for OSN axons to reach the olfactory bulb. (A–D) PLAP staining was used to visualize Fezf1 and Fezf2 expressing cells and their projections. In Fezf1+/−; Fezf2+/− (A) and Fezf1+/− ; Fezf2−/− (C)mice the axons of OSNs (arrows) extended from the MOE and innervated the OB (asterisk). However in Fezf1−/−; Fezf2+/− (B) and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− (D) mice OSN axons (arrowheads) were unable to penetrate the cribriform plate and innervate the OB. Note also the OB is not present in the Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice. The very dark PLAP staining in the OB of Fezf1+/−; Fezf2−/− mice is due to PLAP-labeled axons from deep-layer neurons of the cerebral cortex which projected ectopically into the olfactory bulb. The scale bar in D is 200 μm.

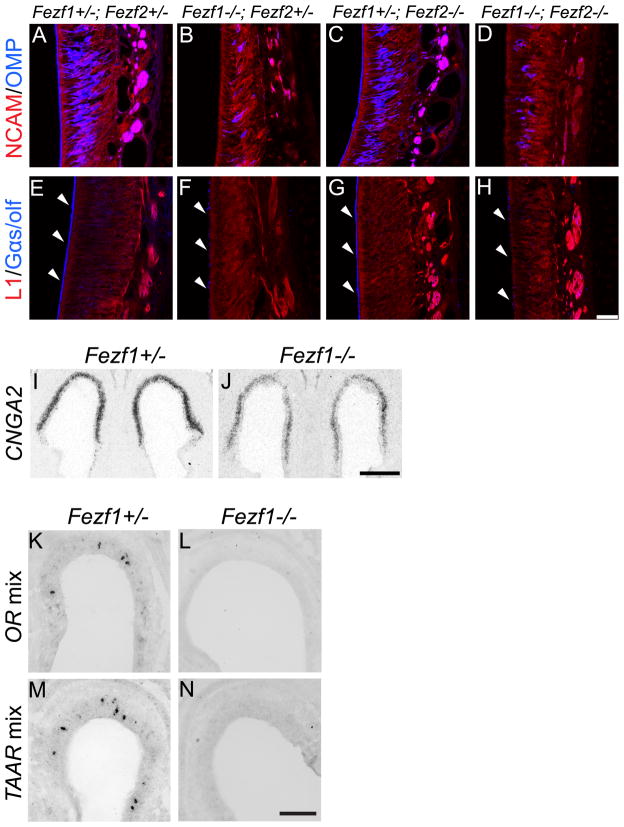

To characterize further the defects in MOE development in Fezf1−/− mice, we performed immunohistochemistry to investigate expression of two markers for mature OSNs: Olfactory Marker Protein (OMP) and the MOE expressed G-protein alpha subunit Gαs/olf. Consistent with a previous report (Watanabe et al., 2009), OMP expression was dramatically decreased in OSNs of Fezf1−/− mice at postnatal day 0 (P0) (Figure 6A and B) and this same phenotype was observed in Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice (Figure 6D). Similar to the defects in OMP expression, we also observed a significant decrease in the expression of Gαs/olf in OSN dendrites from both Fezf1−/− and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− animals (Figure 6E, F and H). Immunostaining for neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) and L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1) did not show any gross defects in MOE organization (Figure 6A–H), suggesting that a pan-neuronal identity was developed in the MOE of Fezf1 mutant mice. Further, the defects in OMP and Gαs/olf expression were not observed in the MOE of Fezf2−/− mice (Figure 6C, G), suggesting that Fezf1, and not Fezf2, is required for MOE-specific maturation.

Figure 6.

The OSNs in the MOE of Fezf1−/− mice fail to mature. Immunohistochemistry shows a reduction in olfactory marker protein (OMP) expression in the MOE of Fezf1−/− (B) and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− (D) compared with control (A) and Fezf2−/− mice (C). Similarly, Gαs/olf expression is markedly reduced in the dendrites (white arrowheads in E–H) of Fezf1−/− (F) and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− (H) when compared with control (E) and Fezf2−/− mice (G). Neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) and L1 cell adhesion molecule (L1) expression both appeared unaffected in Fezf1−/− (B and F), Fezf2−/− (C and G) and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− (D and H) animals. Reduction in CNGA2 expression was visualized by radioactive in situ hybridization for the control and Fezf1 mutant MOE (I and J). Non-radioactive in situ hybridization using probes corresponding to a mixture of olfactory receptors (ORs) (K and L) or trace amine associated receptors (TAARs) (M and N) showed loss of expression in Fezf1−/− animals. Scale bars are H: 75 μm; J: 200 μm; and N: 100 μm.

We next performed in situ hybridization to examine expression of MOE signal transduction components. These included the cyclic nucleotide gated ion channel CNGA2 (Figure 6I, J), a subset of odorant receptors (ORs) (Figure 6K, L) and a subset of trace amine-associated receptors (TAARs) (Figure 6M, N). Consistent with our observations for OMP and Gαs/olf, levels of these transcripts were decreased in the Fezf1−/− MOE compared with controls (Figure 6I–N). Taken together, these data demonstrate that proper MOE-specific development and maturation requires Fezf1 and is not affected by loss of Fezf2.

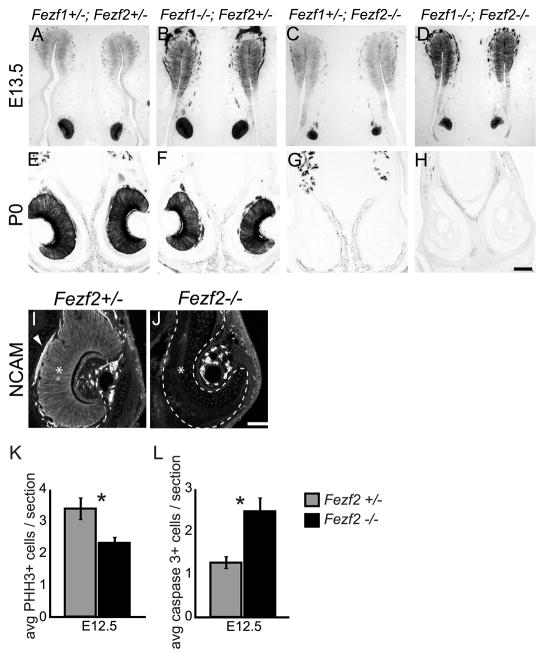

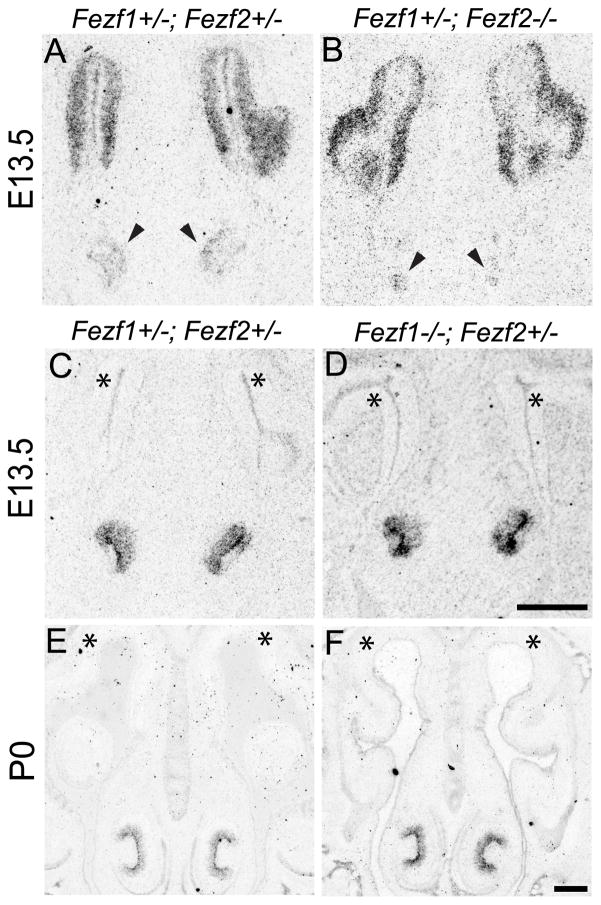

VNO degeneration in Fezf2−/− and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice

The early expression of both Fezf1 and Fezf2 in the VNO suggested they function during VNO development. To test this, we examined VNO development in Fezf1−/−, Fezf2−/−, and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice. Taking advantage of the IRES-PLAP knocked into the Fezf1 and Fezf2 mutant alleles, we used alkaline phosphatase staining to visualize Fezf1 and Fezf2 expressing cells and their axonal projections. At E13.5 the ventromedial region of the olfactory pit separates to give rise to the VNO. We observed normal segregation of the VNO in Fezf1−/−, Fezf2−/−, and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice (Figure 7A–D) but found that VNOs in Fezf1+/−; Fezf2−/−, and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice (Figure 7C, D) appeared smaller than in control or Fezf1−/−; Fef2+/− mice (Figure 7A, B). Strikingly, PLAP-positive cells were totally absent from Fezf1+/−; Fezf2−/− and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− VNOs at P0 and only the surrounding cartilage and supporting tissues remained (Figure 7G, H). Immunostaining for NCAM confirmed this loss of VNO neurons in Fezf1+/−; Fezf2−/− and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice, as NCAM-expressing cells were clearly visible in the VNO of Fezf2+/− but not Fezf2−/− mice (Figure 7I, J). Although Fezf1 was detected at low levels in the developing VNO (Figure 4G–L and G′, L′), we did not observe a significant reduction of PLAP staining in the VNO of Fezf1−/− mice compared to Fezf1+/− (Figure 7A, B, E, and F). Furthermore, degeneration of the nascent VNO in Fezf2−/− mice was not exacerbated by deletion of Fezf1 (compare Figure 7D, H to 7C, G). Taken together, these results indicate that the VNO is initially patterned but subsequently degenerates in Fezf2 deficient mice. Thus, Fezf2 but not Fezf1 is required for maintenance of VNO cells.

Figure 7.

VNO degeneration in Fezf2−/− mice. (A–H) PLAP staining was used to visualize Fezf1 and Fezf2 expressing cells of the olfactory system. At E13.5 the VNO properly separated from the olfactory pit in Fezf1−/−; Fezf2+/−, Fezf1+/−;Fezf2−/−, and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice (A–D). However in Fezf2−/−, and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− animals the VNO is smaller (compare C, D with A, B). This defect is exacerbated by P0, with a complete absence of PLAP-positive cells in Fezf1+/−; Fezf2−/−, and Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− animals (compare G, H to E, F). The loss of neurons in the Fezf2 mutant VNO was confirmed by NCAM staining at P0 (I and J). NCAM+ cells (*) and their axons (arrowhead) are clearly visible in the Fezf2+/− but not in the Fezf2−/− VNO. Quantification of phosphohistone H3 (PHH3+) and cleaved-caspase 3+ cells indicates a significant decrease in proliferation (average of 3.38 vs. 2.31 per VNO section, p = 0.0269) (K) and increase in apoptosis (average of 1.28 vs. 2.48 per VNO section, p = 0.0003) (L). For Fezf2+/−, n = 80 sections and for Fezf2−/−, n = 52 sections. The scale bar in H is 100 μm and in J is 75 μm.

Altered proliferation and apoptosis in the VNO of Fezf2−/− mice

VNO degeneration in Fezf2−/− mice could be the result of decreased proliferation, increased cell death or both factors. To investigate these possibilities we performed immunohistochemistry to assay the number of phosphorylated histone H3 (PHH3)-positive cells and cleaved caspase 3-positive cells. This allowed us to determine the number of mitotic and apoptotic cells, respectively. Upon comparison of serial sections from E12.5 VNOs from Fezf2+/− and Fezf2−/− mice we observed a statistically significant decrease in proliferation and an increase in cell death. Compared to Fezf2+/− VNOs, Fezf2-deficient VNOs showed a 1.5 fold average decrease in PHH3+ cells (Figure 7K) and 1.9 fold average increase in cleaved-caspase 3+ cells per section (Figure 7L). These data indicate that the VNO cells fail to proliferate in Fezf2−/− mice and instead undergo extensive cell death.

Transcriptome analysis of Fezf1−/− OSNs

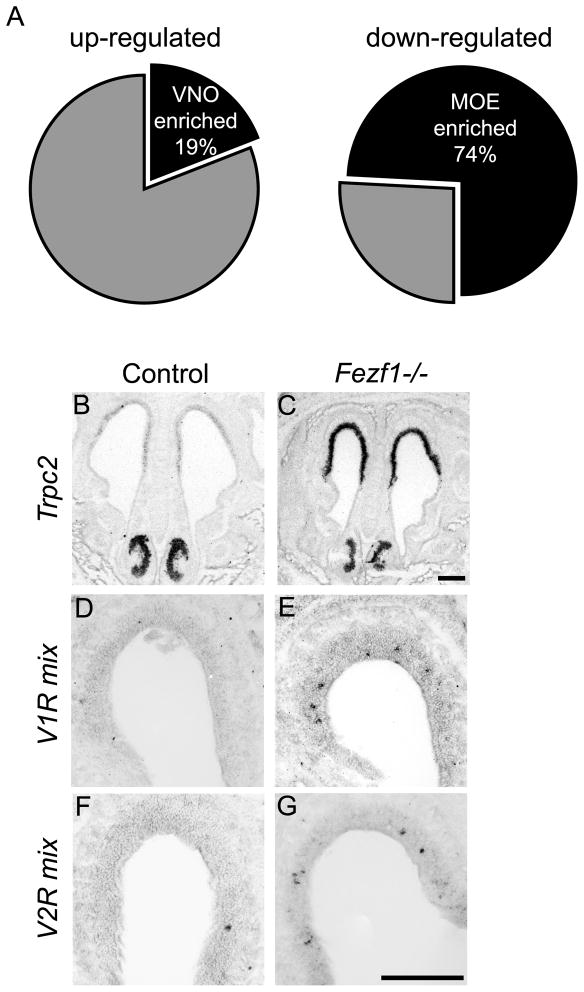

To understand more extensively the function of Fezf1 in olfactory system development, we compared gene expression profiles for Fezf1+/− and Fezf1−/− olfactory cells. We purified EGFP-expressing cells from MOE of E18.5 Fezf1+/− and Fezf1−/− animals, using the EGFP marker present in the Fezf1 mutant allele. Fluorescence activated cell sorting (FACS) allowed us to obtain a population of Fezf1-EGFP expressing cells that was greater than 90% pure. Total RNA from these cells was subjected to expression profiling using Affymetrix microarrays. A pairwise comparison of expression profiles between Fezf1+/− and Fezf1−/− cells yielded a list of 152 up-regulated and 545 down-regulated transcripts. From this list we identified genes as either MOE-or VNO-enriched based upon literature searches and the online expression databases including Alan Brain Atlas (www.brain-map.org) and GenePaint (www.genepaint.org). Among the down-regulated transcripts, 74% corresponded to MOE-enriched genes (Figure 8A), supporting our observation that the MOE fails to mature properly in Fezf1−/− mice. Strikingly, 19% of transcripts up-regulated in Fezf1−/− cells corresponded to VNO-enriched transcripts (Figure 8A). These genes encode VNO receptors, ion channels, components of VNO signal transduction and VNO-specific transcription factors (Table S1). Thus, gene expression analysis demonstrates that in Fezf1−/−mice the MOE fails to mature properly and instead adopts a VNO-like transcriptional identity. Unfortunately, due to the early degeneration of the VNO in Fezf2−/− mice we were not able to perform a similar analysis for Fezf2-expressing VNO cells.

Figure 8.

Fezf1−/− MOE acquires a VNO-like transcriptional identity. Microarray analysis of E18.5 Fezf1−/− cells showed that 74% of down-regulated transcripts and 19% of up-regulated transcripts correspond to MOE- and VNO-enriched transcripts, respectively (A). In situ hybridization confirming mis-expression of VNO-enriched transcripts in the MOE of Fezf1−/− mice (B–G). Transient receptor potential cation channel 2 (Trpc2) (B, C), some vomeronasal receptor class 1 genes (V1Rs) (D, E), and some vomeronasal receptor class 2 genes (V2Rs) (F, G) were mis-expressed in the MOE of Fezf1 mutant animals. Trpc2 expression was visualized by radioactive in situ hybridization. Expression of V1Rs and V2Rs was visualized by digoxigenin in situ hybridization. Scale bars in C and G are 100 μm.

The Fezf1−/− MOE displays a mixed cell identity

Our microarray experiment suggested that cells in the MOE of Fezf1−/− mice adopted the transcriptional identity of the VNO. To examine this further we performed in situ hybridization with VNO-enriched markers on olfactory tissues from Fezf1+/− and Fezf1−/− animals. Consistent with the microarray data, we observed that the MOE in Fezf1−/− mice ectopically expressed components of the VNO signal transduction pathway. The transient receptor potential cation channel 2 gene (Trpc2) is expressed by all vomeronasal sensory neurons (VSNs) and is required for their function (Stowers et al., 2002). In Fezf1+/− mice, Trpc2 is strongly expressed in the VNO and weakly in the MOE (Figure 8B). Strikingly, we observed significant up-regulation of Trpc2 in the MOE of Fezf1−/− animals (Figure 8C). Vomeronasal receptor class 1 and 2 genes (V1Rs and V2Rs, respectively) are important for pheromone detection and their expression is strongly enriched in the VNO. When we compared the expression of V1Rs and V2Rs in Fezf1+/− (Figure 8D, F) and Fezf1−/− mice (Figure 8E, G) we observed their ectopic expression in the MOE. The in situ hybridization data show that the MOE of Fezf1−/− animals expresses VNO-enriched genes. However, since many MOE-enriched genes are still expressed in Fezf1−/− mice (Table S1), these results indicate that in Fezf1−/− mice the MOE only partially acquires a VNO-like identity.

Fezf1 and Fezf2 are not mutually repressive

Two possible mechanisms might have contributed to the expression of VSN-specific genes in the MOE of Fezf1−/− mice. The first possibility was that Fezf1 might regulate the proper sorting and segregation of VNO progenitor cells from MOE progenitor cells. In the absence of Fezf1 function, some VNO progenitors might remain in MOE, leading to VSN-specific gene expression in the MOE. The second possible mechanism was that Fezf1 and Fezf2 might promote MOE and VNO identities, respectively, and accomplish this through mutual repression of each other, such that FEZF1 prevented expression of Fezf2 in the MOE and FEZF2 inhibited expression of Fezf1 in the VNO. Since Fezf2 is a VNO-specific progenitor cell marker, if either possibility was true, we expected Fezf2 expression to be increased in the MOE of Fezf1−/− mice. Thus we performed in situ hybridization at early and late developmental stages on Fezf1−/− and Fezf2−/− mice. We first examined expression of Fezf1 in Fezf2+/− and Fezf2−/− mice at E13.5. At this age we found no evidence demonstrating that loss of Fezf2 affects expression of Fezf1 (Figure 9A, B). This observation is consistent with the fact Fezf2 is not expressed in the MOE during development. Unfortunately, the early degeneration of the VNO in Fezf2−/− mice precluded the examination of Fezf1 expression in the Fezf2 mutant VNO at P0.

Figure 9.

Fezf1 and Fezf2 are not mutually repressive. Radioactive in situ hybridization is used to visualize Fezf1 (A, B) or Fezf2 (C–F) transcripts. At E13.5 expression of Fezf1 is not increased in Fezf2−/− mice (A, B). Similarly, loss of Fezf1 has no effect on expression of Fezf2 at E13.5 or P0 (C–F). The VNO is marked by arrowheads (A, B). The MOE is indicated by asterisks (C–F). Scale bars in D and F are 100 μm.

Next we assayed Fezf2 expression in Fezf1+/− and Fezf1−/− mice at E13.5 and P0. Similar to the results for Fezf1 expression, we did not observe any significant change in the expression levels of Fezf2 in the MOE or VNO after loss of Fezf1 (Figure 9C–F). Consistent with these results, our microarray analysis did not show any increase in Fezf2 expression in purified Fezf1−/− MOE cells at E18.5 (Table S1).

Analysis of Fezf1−/− and Fezf2−/− mice suggests that VNO progenitor cells segregate properly from MOE progenitors in the Fezf1−/− mice, and Fezf1 does not promote MOE neuronal fate by repressing Fezf2 expression in the MOE. Furthermore, olfactory development in the Fezf1−/−; Fezf2−/− mice was the sum of defects observed in Fezf1−/− and Fezf2−/− single mutant mice: expression of VNO-enriched genes is up-regulated in the MOE and the VNO quickly degenerates around E12.5–E13.5. Thus, both transcriptional and genetic analysis demonstrated that Fezf1 and Fezf2 do not exhibit mutually repressive interactions during olfactory development.

Fezf1 and Fezf2 can function interchangeably in cell fate specification during development of the cerebral cortex

The lack of genetic and molecular evidence for cross-inhibition between Fezf1 and Fezf2 prompted us to explore other possible mechanisms underlying their functions. The sequences of FEZF1 and FEZF2 proteins show a high degree of similarity. They both contain a putative C-terminal DNA binding domain consisting of 6 C2H2 zinc-finger motifs and a N-terminal region with homology to the engrailed repressor domain, which can interact with the groucho/TLE family of co-repressors (Figure 10A) (Shimizu and Hibi, 2009). In fact, the zinc-finger motifs of these two proteins are 97% identical (Figure 10A). This high degree of similarity in their DNA binding domains suggests that FEZF1 and FEZF2 have the capacity to bind the same DNA regulatory sequences and likely regulate similar sets of genes.

The expression patterns of Fezf1 and Fezf2 during olfactory system development and the phenotype of Fezf1−/− mice are consistent with the hypothesis that they regulate common gene targets. As development of the olfactory system proceeds, Fezf1 and Fezf2 are down-regulated in VSNs while their expression in OSNs and VNO supporting cells increases. Additionally, the up-regulation of VSN-enriched genes in the MOE of Fezf1−/− mice suggests that both Fezf1 and Fezf2 might function to repress VSN-enriched gene expression in the MOE and supporting cells of the VNO. Thus, we hypothesized that Fezf1 and Fezf2 may function to inhibit a VSN fate within MOE neurons and VNO supporting cells, respectively (Figure 10M). To test this, we performed a mis-expression assay to ascertain whether Fezf1 and Fezf2 can function interchangeably in cell fate specification. Instead of using the olfactory system, we performed this assay in the developing cerebral cortex, since this brain region is much more amenable for surgical manipulation to test gene function in vivo.

During development of the cerebral cortex, Fezf1 is not expressed in cortical neurons (Hirata et al., 2006a; Shimizu et al., 2010). However, Fezf2 is expressed in subcortical projection neurons of the cerebral cortex and is both necessary and sufficient for the development of subcortical axons (Chen et al., 2005a; Chen et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2005b; Molyneaux et al., 2005). Previously we have demonstrated that misexpression of Fezf2 in corticocortical projection neurons prevents these neurons from sending axons to other cortical areas (their normal axon targets), and instead redirects their axons to subcortical targets such as the thalamus and spinal cord (Chen et al., 2008). To test whether FEZF1 and FEZF2 can regulate similar sets of genes, we ectopically expressed Fezf1 in corticocortical projection neurons and assayed the effects on their axonal projections. Plasmids encoding the FEZF1 protein under control of the cytomegalovirus (CMV) early gene promoter and chicken β-actin enhancer were introduced into corticocortical projection neurons at E15.5 using in utero electroporation. Additionally, plasmids encoding the EGFP protein under the same promoter and enhancer were co-electroporated to label cell bodies and axons of the electroporated neurons. Following surgery the embryos were returned to the abdomens of pregnant female mice and allowed to develop to full term. Brains from the electroporated embryos were collected at P5. In brains electroporated with EGFP plasmids alone, GFP labeled axons are present in the striatum (Figure 10D) but not in the thalamus (Figure 10E) or the pons (Figure 10F), which are the axonal targets of subcortical neurons. Strikingly, in brains electroporated with FEZF1 and EGFP expressing plasmids, many GFP labeled axons are present in the striatum (Figure 10J), thalamus (Figure 10K), and pons (Figure 10L), similar to the effect of mis-expressing FEZF2 in corticocortical projection neurons (Chen et al., 2008). This result demonstrates that FEZF1 and FEZF2 can regulate expression of common genes in vivo.

Discussion

The mechanisms specifying the MOE and VNO, two functionally and anatomically distinct organs, from a common olfactory pit have not been well defined. In this study we focused on the functions of two zinc-finger transcription factors Fezf1 and Fezf2 in murine olfactory development. We found that Fezf2 is required for survival and proliferation of VNO progenitors and that Fezf1 regulates the maturation and identity of MOE sensory neurons.

During development, Fezf1 and Fezf2 are expressed in the olfactory pit at an early stage and demarcate distinct regions of the olfactory primordium. While Fezf1-expressing cells are distributed along the full length of the olfactory pit, Fezf2 expression is restricted to the ventromedial region that gives rise to the VNO, making Fezf2 the earliest marker for future VNO cells. Immediately after the VNO segregates from the MOE at E13.5, Fezf1 is expressed in both the MOE and VNO. After E14.5, while Fezf1 expression in OSNs and progenitors of the MOE steadily increases, its expression in the VNO decreases, and very few VNO sensory neurons still express Fezf1 at birth. Conversely, Fezf2 expression in the VNO is dynamic; prior to E14.5, Fezf2 is expressed throughout the VNO neuroepithelium. After E14.5, when supporting cells and VSNs segregate into distinct layers, Fezf2 expression becomes restricted to the sustentacular cell layer and is excluded from differentiating VSNs. These specific and dynamic expression patterns of Fezf1 and Fezf2 suggest that they regulate cell identity during olfactory system development.

Indeed, in the developing cerebral cortex Fezf2 plays an essential role in establishing projection neuron identity. In the cerebral cortex, Fezf2 is initially expressed in progenitor cells. When neurogenesis begins, Fezf2 expression is restricted to subcortical projection neurons and regulates their identities (Chen et al., 2005a; Chen et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2005b; Hirata et al., 2006a; Molyneaux et al., 2005; Shimizu et al., 2010). In Fezf2−/− mice, the subcerebral neurons fail to develop and instead adopt the identities of alternative projection neuron subtypes; they express molecular markers of callosal and corticothalamic neurons and project axons to the normal targets of callosal and corticothalamic neurons (Chen et al., 2005a; Chen et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2005b; Molyneaux et al., 2005). Current literature supports the idea that Fezf2 promotes subcerebral neuron identity by repressing alternative callosal and corticothalamic fates (Chen et al., 2008).

The dynamic expression pattern of Fezf2 in the olfactory system is very similar to that observed in the cerebral cortex. It is expressed in VNO precursor cells before E14.5. However, when supporting cells are generated, Fezf2 expression becomes restricted to the sustentacular cells and excluded from VNO neurons. Based on a similarly dynamic expression pattern for Fezf2 in the cerebral cortex and VNO, and the mechanisms of Fezf2 regulation of projection neuron identities in the cerebral cortex, we propose that Fezf2 promotes supporting cell identity by repressing expression of VSN enriched genes. Unfortunately, the early and rapid degeneration of the VNO in Fezf2−/− mice prevented us from directly investigating whether Fezf2 represses VNO sensory neuron identity in supporting cells.

Fezf1 is essential for the axons of OSNs to project into the olfactory bulb (Hirata et al., 2006b; Watanabe et al., 2009). In our study, we found that, in addition to regulating axonal development, Fezf1 regulates the development of OSNs in the MOE through repression of VSN-enriched genes. In Fezf1−/− mice, the expression of many MOE-enriched genes is reduced and we observed ectopic expression of many VNO-enriched genes. These results demonstrate that by repressing VSN-enriched gene expression, Fezf1 ensures that OSNs fully differentiate and mature. Since olfactory axons do not reach the olfactory bulb in Fezf1−/− mice, possibly due to a failure to penetrate the basal lamina layer of the brain (Watanabe et al., 2009), we are unable to determine whether the target choice of Fezf1 mutant OSNs is switched from the main olfactory bulb to the accessory olfactory bulb.

There are two identifiable protein domains in the FEZ proteins: an engrailed homology domain and the zinc-finger motifs. Both protein domains are almost identical between FEZF1 and FEZF2, suggesting that they can regulate common gene targets. Indeed, we observed the same effects on axonal targeting when either FEZF1 or FEZF2 was mis-expressed in corticocortical projection neurons in the cerebral cortex. Recently, Shimizu et al. reported that FEZF1 and FEZF2 both directly repress transcription of Hes5 (Shimizu et al., 2010). This report and our results are consistent with the hypothesis that Fezf1 and Fezf2 regulate cell fate during development of the olfactory system through repression of VSN-enriched genes in either progenitors and sensory neurons of the MOE or supporting cells of the VNO.

Our study helps to illuminate the molecular mechanisms that regulate the contrasting identities of the MOE and VNO, two functionally and anatomically distinct organs that arise from a common placode during development. Separate olfactory subsystems first appeared in the aquatic ancestors of modern tetrapods, and this subsystem organization has been maintained in primates (Swaney and Keverne, 2009). We propose that Fezf1 and Fezf2 function to prevent OSNs in the MOE and supporting cells in the VNO from assuming a VNO sensory neuron identity. FEZF1 and FEZF2 likely accomplish this task either through activation or repression of target genes. The mixed cell identities observed in the MOE of Fezf1−/− mice suggests that, although Fezf1 plays an important role in repressing VSN identity, there are likely other key regulators that act either upstream or in parallel to promote OSN fate specification.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We are greatly indebted to Chris Kaznowski and Han Ly for help with in situ hybridizations and Tyler Cutforth for help both with in situ hybridizations and critical reading of the manuscript. We would like to think Bari Holm Nazario and members of the Foresberg lab for assistance with FACS. We are grateful to Lily Shiue and the Ares Lab for help with microarrays. Members of the Chen Lab and Feldheimn Lab and Dr. Lindsay Hinck provided helpful discussion during the completion of these experiments. We thank Dr. Ron Yu (Stowers Institute) for providing DNA templates for in situ probes. This work was supported by a Basil O’Connor Starter Scholar Research Award from March of Dimes Foundation (to BC) and NIH EY08411 (to SKM).

Literature Cited

- Baker H, Grillo M, Margolis FL. Biochemical and immunocytochemical characterization of olfactory marker protein in the rodent central nervous system. J Comp Neurol. 1989;285(2):246–261. doi: 10.1002/cne.902850207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balmer CW, LaMantia AS. Noses and neurons: induction, morphogenesis, and neuronal differentiation in the peripheral olfactory pathway. Dev Dyn. 2005;234(3):464–481. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beites CL, Kawauchi S, Crocker CE, Calof AL. Identification and molecular regulation of neural stem cells in the olfactory epithelium. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306(2):309–316. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cau E, Casarosa S, Guillemot F. Mash1 and Ngn1 control distinct steps of determination and differentiation in the olfactory sensory neuron lineage. Development. 2002;129(8):1871–1880. doi: 10.1242/dev.129.8.1871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cau E, Gradwohl G, Casarosa S, Kageyama R, Guillemot F. Hes genes regulate sequential stages of neurogenesis in the olfactory epithelium. Development. 2000;127(11):2323–2332. doi: 10.1242/dev.127.11.2323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cau E, Gradwohl G, Fode C, Guillemot F. Mash1 activates a cascade of bHLH regulators in olfactory neuron progenitors. Development. 1997;124(8):1611–1621. doi: 10.1242/dev.124.8.1611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Schaevitz LR, McConnell SK. Fezl regulates the differentiation and axon targeting of layer 5 subcortical projection neurons in cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005a;102(47):17184–17189. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0508732102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen B, Wang SS, Hattox AM, Rayburn H, Nelson SB, McConnell SK. The Fezf2-Ctip2 genetic pathway regulates the fate choice of subcortical projection neurons in the developing cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105(32):11382–11387. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0804918105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JG, Rasin MR, Kwan KY, Sestan N. Zfp312 is required for subcortical axonal projections and dendritic morphology of deep-layer pyramidal neurons of the cerebral cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005b;102(49):17792–17797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509032102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen NR, Taylor JS, Scott LB, Guillery RW, Soriano P, Furley AJ. Errors in corticospinal axon guidance in mice lacking the neural cell adhesion molecule L1. Curr Biol. 1998;8(1):26–33. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)70017-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dulac C, Torello AT. Molecular detection of pheromone signals in mammals: from genes to behaviour. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2003;4(7):551–562. doi: 10.1038/nrn1140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong S, Zheng C, Doughty ML, Losos K, Didkovsky N, Schambra UB, Nowak NJ, Joyner A, Leblanc G, Hatten ME, Heintz N. A gene expression atlas of the central nervous system based on bacterial artificial chromosomes. Nature. 2003;425(6961):917–925. doi: 10.1038/nature02033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gordon MK, Mumm JS, Davis RA, Holcomb JD, Calof AL. Dynamics of MASH1 expression in vitro and in vivo suggest a non-stem cell site of MASH1 action in the olfactory receptor neuron lineage. Mol Cell Neurosci. 1995;6(4):363–379. doi: 10.1006/mcne.1995.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guillemot F, Lo LC, Johnson JE, Auerbach A, Anderson DJ, Joyner AL. Mammalian achaete-scute homolog 1 is required for the early development of olfactory and autonomic neurons. Cell. 1993;75(3):463–476. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90381-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata T, Nakazawa M, Muraoka O, Nakayama R, Suda Y, Hibi M. Zinc-finger genes Fez and Fez-like function in the establishment of diencephalon subdivisions. Development. 2006a;133(20):3993–4004. doi: 10.1242/dev.02585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirata T, Nakazawa M, Yoshihara S, Miyachi H, Kitamura K, Yoshihara Y, Hibi M. Zinc-finger gene Fez in the olfactory sensory neurons regulates development of the olfactory bulb non-cell-autonomously. Development. 2006b;133(8):1433–1443. doi: 10.1242/dev.02329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hirota J, Mombaerts P. The LIM-homeodomain protein Lhx2 is required for complete development of mouse olfactory sensory neurons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101(23):8751–8755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400940101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inaki K, Takahashi YK, Nagayama S, Mori K. Molecular-feature domains with posterodorsal-anteroventral polarity in the symmetrical sensory maps of the mouse olfactory bulb: mapping of odourant-induced Zif268 expression. Eur J Neurosci. 2002;15(10):1563–1574. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2002.01991.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kawauchi S, Beites CL, Crocker CE, Wu HH, Bonnin A, Murray R, Calof AL. Molecular signals regulating proliferation of stem and progenitor cells in mouse olfactory epithelium. Dev Neurosci. 2004;26(2–4):166–180. doi: 10.1159/000082135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolterud A, Alenius M, Carlsson L, Bohm S. The Lim homeobox gene Lhx2 is required for olfactory sensory neuron identity. Development. 2004;131(21):5319–5326. doi: 10.1242/dev.01416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LaMantia AS, Bhasin N, Rhodes K, Heemskerk J. Mesenchymal/epithelial induction mediates olfactory pathway formation. Neuron. 2000;28(2):411–425. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)00121-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laub F, Aldabe R, Friedrich V, Jr, Ohnishi S, Yoshida T, Ramirez F. Developmental expression of mouse Kruppel-like transcription factor KLF7 suggests a potential role in neurogenesis. Dev Biol. 2001;233(2):305–318. doi: 10.1006/dbio.2001.0243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi G, Puche AC, Mantero S, Barbieri O, Trombino S, Paleari L, Egeo A, Merlo GR. The Dlx5 homeodomain gene is essential for olfactory development and connectivity in the mouse. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2003;22(4):530–543. doi: 10.1016/s1044-7431(02)00041-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liman ER, Buck LB. A second subunit of the olfactory cyclic nucleotide-gated channel confers high sensitivity to cAMP. Neuron. 1994;13(3):611–621. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(94)90029-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long JE, Garel S, Depew MJ, Tobet S, Rubenstein JL. DLX5 regulates development of peripheral and central components of the olfactory system. J Neurosci. 2003;23(2):568–578. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-02-00568.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo Y, Hurwitz J, Massague J. Cell-cycle inhibition by independent CDK and PCNA binding domains in p21Cip1. Nature. 1995;375(6527):159–161. doi: 10.1038/375159a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marcucci F, Zou DJ, Firestein S. Sequential onset of presynaptic molecules during olfactory sensory neuron maturation. J Comp Neurol. 2009;516(3):187–198. doi: 10.1002/cne.22094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matarazzo V, Cohen D, Palmer AM, Simpson PJ, Khokhar B, Pan SJ, Ronnett GV. The transcriptional repressor Mecp2 regulates terminal neuronal differentiation. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2004;27(1):44–58. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molyneaux BJ, Arlotta P, Hirata T, Hibi M, Macklis JD. Fezl is required for the birth and specification of corticospinal motor neurons. Neuron. 2005;47(6):817–831. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mombaerts P. Genes and ligands for odorant, vomeronasal and taste receptors. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2004;5(4):263–278. doi: 10.1038/nrn1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munger SD, Leinders-Zufall T, Zufall F. Subsystem organization of the mammalian sense of smell. Annu Rev Physiol. 2009;71:115–140. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray RC, Navi D, Fesenko J, Lander AD, Calof AL. Widespread defects in the primary olfactory pathway caused by loss of Mash1 function. J Neurosci. 2003;23(5):1769–1780. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-05-01769.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ronnett GV, Leopold D, Cai X, Hoffbuhr KC, Moses L, Hoffman EP, Naidu S. Olfactory biopsies demonstrate a defect in neuronal development in Rett’s syndrome. Ann Neurol. 2003;54(2):206–218. doi: 10.1002/ana.10633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaeren-Wiemers N, Gerfin-Moser A. A single protocol to detect transcripts of various types and expression levels in neural tissue and cultured cells: in situ hybridization using digoxigenin-labelled cRNA probes. Histochemistry. 1993;100(6):431–440. doi: 10.1007/BF00267823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schellinck HM, Arnold A, Rafuse VF. Neural cell adhesion molecule (NCAM) null mice do not show a deficit in odour discrimination learning. Behav Brain Res. 2004;152(2):327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2003.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Hibi M. Formation and patterning of the forebrain and olfactory system by zinc-finger genes Fezf1 and Fezf2. Dev Growth Differ. 2009;51(3):221–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2009.01088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu T, Nakazawa M, Kani S, Bae YK, Kageyama R, Hibi M. Zinc finger genes Fezf1 and Fezf2 control neuronal differentiation by repressing Hes5 expression in the forebrain. Development. 2010;137(11):1875–1885. doi: 10.1242/dev.047167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stowers L, Holy TE, Meister M, Dulac C, Koentges G. Loss of sex discrimination and male-male aggression in mice deficient for TRP2. Science. 2002;295(5559):1493–1500. doi: 10.1126/science.1069259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swaney WT, Keverne EB. The evolution of pheromonal communication. Behav Brain Res. 2009;200(2):239–247. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2008.09.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka H, Yamashita T, Asada M, Mizutani S, Yoshikawa H, Tohyama M. Cytoplasmic p21(Cip1/WAF1) regulates neurite remodeling by inhibiting Rho-kinase activity. J Cell Biol. 2002;158(2):321–329. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200202071. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taniguchi M, Nagao H, Takahashi YK, Yamaguchi M, Mitsui S, Yagi T, Mori K, Shimizu T. Distorted odor maps in the olfactory bulb of semaphorin 3A-deficient mice. J Neurosci. 2003;23(4):1390–1397. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-04-01390.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wagner N, Wagner KD, Hammes A, Kirschner KM, Vidal VP, Schedl A, Scholz H. A splice variant of the Wilms’ tumour suppressor Wt1 is required for normal development of the olfactory system. Development. 2005;132(6):1327–1336. doi: 10.1242/dev.01682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Betz AG, Reed RR. Cloning of a novel Olf-1/EBF-like gene, O/E-4, by degenerate oligo-based direct selection. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2002;20(3):404–414. doi: 10.1006/mcne.2002.1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Lewcock JW, Feinstein P, Mombaerts P, Reed RR. Genetic disruptions of O/E2 and O/E3 genes reveal involvement in olfactory receptor neuron projection. Development. 2004;131(6):1377–1388. doi: 10.1242/dev.01009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang SS, Tsai RY, Reed RR. The characterization of the Olf-1/EBF-like HLH transcription factor family: implications in olfactory gene regulation and neuronal development. J Neurosci. 1997;17(11):4149–4158. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-11-04149.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe Y, Inoue K, Okuyama-Yamamoto A, Nakai N, Nakatani J, Nibu K, Sato N, Iiboshi Y, Yusa K, Kondoh G, Takeda J, Terashima T, Takumi T. Fezf1 is required for penetration of the basal lamina by olfactory axons to promote olfactory development. J Comp Neurol. 2009;515(5):565–584. doi: 10.1002/cne.22074. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.