Background: Dbf4, the regulatory subunit of Cdc7, has essential roles in initiation of DNA replication and checkpoint activation.

Results: We have identified the domain of Dbf4 that is necessary and sufficient for the interaction with Rad53.

Conclusion: The structural integrity of this domain is essential for Dbf4-Rad53 interaction.

Significance: This work suggests how single BRCT domains can be adapted to form complex functional units.

Keywords: Checkpoint Control, Protein Structure, Protein-Protein Interactions, X-ray Crystallography, Yeast Genetics, BRCT, Dbf4-dependent Kinase (DDK), FHA Domain, Rad53

Abstract

Dbf4 is a conserved eukaryotic protein that functions as the regulatory subunit of the Dbf4-dependent kinase (DDK) complex. DDK plays essential roles in DNA replication initiation and checkpoint activation. During the replication checkpoint, Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dbf4 is phosphorylated in a Rad53-dependent manner, and this, in turn, inhibits initiation of replication at late origins. We have determined the minimal region of Dbf4 required for the interaction with the checkpoint kinase Rad53 and solved its crystal structure. The core of this fragment of Dbf4 folds as a BRCT domain, but it includes an additional N-terminal helix unique to Dbf4. Mutation of the residues that anchor this helix to the domain core abolish the interaction between Dbf4 and Rad53, indicating that this helix is an integral element of the domain. The structure also reveals that previously characterized Dbf4 mutants with checkpoint phenotypes destabilize the domain, indicating that its structural integrity is essential for the interaction with Rad53. Collectively, these results allow us to propose a model for the association between Dbf4 and Rad53.

Introduction

The Dbf4-dependent kinase (DDK)4 complex acts as the ultimate trigger of DNA replication by phosphorylating protein targets found at origins. Essential in all eukaryotic cells, DDK is a heterodimer composed of the Cdc7 kinase and its regulatory subunit Dbf4 (1). Although the levels of Cdc7 are constant throughout the cell cycle, Dbf4 is only synthesized late in G1 phase and is subsequently degraded during mitosis, causing the kinase activity of Cdc7 to cycle accordingly (2–5). Beyond activating origins of replication, the DDK complex also participates in other cellular processes, including meiosis (6–8), mitotic exit (9), and the intra-S phase checkpoint (10, 11). This latter function is especially important because it acts to suppress further origin firing as well as to stabilize and ultimately restart stalled replication forks, which otherwise would become sites of genetic instability.

Rad53 is an effector kinase of the replication checkpoint in Saccharomyces cerevisiae that delays entry into M phase and suppresses harmful rearrangements of DNA (12–15). Rad53 is activated through hyperphosphorylation mediated both by Rad53 in trans and additional kinases (16, 17). DDK phosphorylates Rad53 in vitro, and deletion of Cdc7 from yeast cells prevents Rad53 from achieving its hyperphosphorylated state, leading to an increased sensitivity to genotoxic stress (18). Reciprocally, Dbf4 is one of the Rad53 targets during the checkpoint response, causing a significant reduction in Cdc7 kinase activity toward Mcm2 (18). This prevents licensed origins that have not yet fired from initiating replication (11, 19). Collectively, this suggests that DDK is both an upstream regulator of Rad53 and a downstream target during the replication checkpoint.

Among Dbf4 homologues, only three short sequences are conserved. They are referred to as motifs N, M, and C to denote their location in the polypeptide chain (20). Motifs M and C (residues 260–309 and 656–697, respectively, in S. cerevisiae Dbf4) are required to bind and activate Cdc7 (21), whereas motif N (residues 135–179 in S. cerevisiae Dbf4) is necessary for the interaction with Rad53 and the origin recognition complex (22, 23). Deletions or point mutations within motif N of Dbf4 manifest as an increased sensitivity to the ribonucleotide reductase inhibitor hydroxyurea and DNA-damaging agents, suggesting that these mutants have an inefficient checkpoint response (23, 24). An interaction between the human homologue of Dbf4 (ASK) and the checkpoint kinase Chk1 has also been described. Chk1 mediates the S phase checkpoint response in higher eukaryotes and phosphorylates ASK in vitro (25). Although it remains unclear whether the human DDK complex plays the same role in the checkpoint as the yeast DDK complex.

Rad53 contains two Forkhead-associated (FHA) domains. Dbf4 primarily interacts with the FHA1 domain of Rad53, although it also has weak affinity for the FHA2 domain of the protein (22, 23). The FHA1 domain of Rad53 specifically recognizes phosphothreonine residues found in unstructured loops (26). Therefore, the interaction between Rad53 and most of its binding partners can be recreated using phosphothreonine-containing peptides. Because mutation of the FHA1 phosphate-binding pocket compromises the ability of this domain to recognize Dbf4, it was originally proposed that Rad53 would recognize a phosphoepitope within Dbf4 (22). However, the phosphothreonine in Dbf4 responsible for this interaction has not been identified. Recent studies have unveiled additional phosphorylation-independent modes of interaction by which FHA domains can interact with their binding partners (27, 28). One of these modes of interaction still involves the phosphate-binding pocket of the FHA domain (27), indicating that the interaction between Dbf4 and Rad53 could also be phosphorylation-independent.

It has been proposed that motif N is part of a larger structurally conserved unit that resembles a BRCT domain (3, 24). In support of this idea, motif N does not constitute an independent folding unit by itself, but the region of Dbf4 encompassing residues 120–250 can be overproduced on its own, and it is well behaved in solution (29). BRCT domains are commonly found in proteins that respond to DNA damage, and many of them function as tandem repeats, which associate together using conserved hydrophobic residues to create an intervening hydrophobic pocket (30, 31). These repeats act as a single unit to recognize binding partners by using both this pocket as well as a phosphoserine binding site contained within one of the BRCT domains (32). However, the mechanism by which single BRCT domains, such as the one presumably present in Dbf4, participate in protein-protein interactions is poorly understood.

In an effort to clarify whether Dbf4 has a bona fide BRCT domain and whether this domain mediates the interaction with Rad53, we have characterized the minimal region of Dbf4 necessary for the interaction with Rad53 and determined its crystal structure. We have found that the fragment of Dbf4 encompassing residues 105–221 is sufficient to mediate this interaction. The crystal structures of this sufficient domain of Dbf4 and a shorter fragment encompassing residues 120–221 unveil a structural feature that is unique to Dbf4. Residues 120–221 fold as a bona fide BRCT domain, but residues 105–119 form an α-helix that is embedded in the core of the domain defining a novel structure that we name Helix-BRCT (H-BRCT). Using a combination of structure-guided site-directed mutagenesis and yeast two-hybrid analysis, we demonstrate that the presence of this N-terminal helix is critical for both folding of the domain and the interaction with Rad53. Collectively, our work demonstrates that the structural integrity of the H-BRCT domain is essential for the ability of Dbf4 to interact with Rad53 and promote cell survival under genotoxic stress.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Purification and Crystallization

The His-tagged version of the BRCT domain of Dbf4 was obtained by transforming the pAG8206 plasmid encoding residues 120–250 from S. cerevisiae Dbf4 (NP_010337) in either BL21(DE3) or B834(DE3) cells carrying the pRARELysS plasmid. SeMet-labeled protein was subsequently overproduced in minimal media supplemented with SeMet as described earlier (33). Protein overproduction and purification for both native and SeMet-labeled Dbf4 was performed as described previously (29). The histidine tag was removed with thrombin (Sigma), and the protein was further purified by ionic exchange in a MonoS (10/100) GL column (GE Healthcare). Purified tagged and untagged Dbf4 were concentrated to 5 mg/ml in 20 mm Tris, pH 8.0, 1 mm DTT, 100 mm NaCl, and 5% glycerol (storage buffer). Longer fragments of Dbf4 (encoding residues 65–221 and 105–220, pAG8391 and pAG8209, respectively) were produced and purified similarly. Protein concentration was determined using the Beer-Lambert law with an extinction coefficient of 23,950 m−1 cm−1.

SeMet crystals of a His6-tagged Dbf4 fragment encompassing the predicted BRCT domain (residues 120–250) were grown using the hanging drop method in 0.1 m Tris, pH 8.5, 0.05 m MgCl2 and 29% PEG 400 (v/v). Native crystals of the untagged BRCT domain were grown in 100 mm sodium/potassium phosphate buffer, pH 7.1, and 22% MPD (v/v) and cryoprotected by increasing the MPD concentration to 40% (v/v). Crystals of the minimal domain of Dbf4 sufficient for the interaction with Rad53 (residues 65–221, Helix-BRCT) were grown in 1.9 m (NH4)2SO4, 0.014 m MgSO4, 0.05 m (CH3)2AsO2Na, pH 6.5, and 0.03 mm CYMAL-7, improved by streak seeding, and cryoprotected by the addition of 20% glycerol to the mother liquor prior to data collection. All crystals were grown from crystallization drops set at 4 °C by mixing 1 μl of protein with 1 μl of reservoir solution.

Complete data sets of SeMet-labeled tagged and untagged BRCT domain crystals were collected using the X29 beamline, whereas data for the crystals of the Helix-BRCT domain were collected using the X25 beamline at the National Synchrotron Light Source (Brookhaven National Laboratory). All data sets were processed with HKL2000 (34) (Table 1).

TABLE 1.

Data collection and refinement

| Dbf4 fragment | Residues 120–250 (including His tag) | Residues 120–250 (without His tag) | Residues 65–220 (without His tag) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data collection | |||

| Space group | P21 | P21212 | P6422 |

| Unit cell (Å) | a = 90.2, b = 79.4, c = 127.4 | a = 83.7, b = 99.7, c = 127.0 | a = b = 83.7, c = 103.7 |

| α = γ = 90°, β = 110.7° | α = β = γ = 90° | α = β = 90°, γ = 120° | |

| Matthews coefficient (Å3 Da−1) | 2.44 | 3.44 | 2.78 |

| Solvent content (%) | 49.6 | 64.2 | 55.9 |

| Wavelength (Å) | 0.9796 | 1.081 | 1.1 |

| Monomers in asymmetric unit | 10 | 5 | 1 |

| Resolution (Å) a | 50–2.70 (2.75–2.70) | 50–2.40 (2.44–2.40) | 50–2.69 (2.74–2.69) |

| Completeness (%)a | 99.3 (99.1) | 99.8 (100) | 99.7 (99.7) |

| Rmerge (%)a | 0.10 (0.79) | 0.192 (0.74) | 0.06 (0.42) |

| I/σ(I) a | 16.9 (2.8) | 8.9 (2.6) | 31.0 (3.5) |

| Redundancya | 7.0 (7.2) | 6.2 (5.9) | 6.9 (6.2) |

| Reflections (total) | 323,273 | 262,516 | 43,786 |

| Reflections (unique) | 46,033 | 42,318 | 6,280 |

| Refinement | |||

| Resolution (Å) | 35.5–2.7 | 46.4–2.4 | 38.8–2.69 |

| Reflections (Rwork/Rfree) | 44,042/2,233 | 42,245/2,146 | 6,061/300 |

| Rwork/Rfree (%) | 20.5/24.4 | 20.3/22.9 | 22.4/27.3 |

| No. of atoms | |||

| Protein | 8,276 | 4,362 | 1,058 |

| Solvent | 99 | 230 | 10 |

| Root mean square deviations | |||

| Bonds (Å) | 0.009 | 0.007 | 0.008 |

| Angles (degrees) | 1.161 | 0.959 | 1.034 |

| Ramachandran plot (%) | |||

| Most favored | 93.6 | 94.2 | 94.0 |

| Additionally allowed | 6.2 | 5.8 | 6.0 |

a Data in the highest resolution shell are shown in parentheses.

Structure Determination and Refinement

The structure of the His-tagged BRCT domain was determined by the single anomalous diffraction method. Thirty of the 40 selenium sites were found and refined using standard protocols in PHENIX (35). The initial model was refined by iterative cycles of manual model building in Coot (36) and refinement using PHENIX and imposing non-crystallographic symmetry constraints that related the 10 molecules in the asymmetric unit pairwise. This protocol yielded a final model that includes residues 122–224 and has 93.6% of the residues in the most favored region of the Ramachandran plot and none in the disallowed regions. One BRCT monomer from this structure was subsequently used as the search model to solve the structure of the untagged BRCT domain using molecular replacement with Phaser (37). The structure of the untagged BRCT domain was refined using standard protocols in Coot and PHENIX, and the final model includes residues 119–242 for one of the five monomers in the asymmetric unit and residues 122–220 for the other four, has 94.2% of the residues in the most favored region of the Ramachandran plot, and has none in the disallowed regions.

The structure of the sufficient domain (H-BRCT) was solved by molecular replacement using the BRCT domain as the search model. The final model includes residues 98–220 and has 94% residues in the most favored regions of the Ramachandran plot and none in the disallowed regions. The refinement statistics for the three structures are presented in Table 1. Figures depicting molecular structures were generated using PyMOL (38).

Two-hybrid Analysis

Two-hybrid analysis was carried out as described previously (23, 39). pEG-Dbf4-FL was used to express full-length wild-type Dbf4 bait, whereas pJG-Rad53 was used to express Rad53 prey (22, 23). Additional two-hybrid bait constructs expressing various regions of Dbf4 were cloned by PCR using pPD32 as template (40) and forward and reverse primers including 5′ EcoRI and XhoI sites, respectively, with sequences at the 3′-end complementary to the appropriate regions of DBF4. PCR products were digested with EcoRI and XhoI and ligated into pEG-202 (41) digested with the same enzymes. Dbf4 variants encompassing point mutations were generated using QuikChange (Invitrogen) and verified by DNA sequencing (MOBIX, McMaster University; Robarts Research Institute).

Plasmid Shuffle Growth Spotting Assays

Diploid budding yeast strain DY-13 (MATa/α, his3Δ1/his3Δ1, leu2Δ0/leu2Δ0, met15Δ0/+, lys2Δ0/+, ura3Δ0/ura3Δ0, kanR::DBF4/+) was transformed with pCM190-Dbf4-FL (22). Following sporulation, a haploid pCM190-Dbf4-FL/ΔDBF4 strain was established. Plasmid shuffle with this strain was then carried out using CEN vector pPD32 expressing DBF4 under its natural promoter (40) or one of the mutant variants described below, following standard procedures (42). Bsu36I fragments from pEG-Dbf4-T171R and pEG-Dbf4 ΔN (23) were used to replace the equivalent DBF4 fragment of pPD32, to generate pPD32-T171R and pPD32-Δ135–179, respectively. Growth spotting assays were performed as described previously (23).

RESULTS

Motif N of Dbf4 Is Part of BRCT Domain

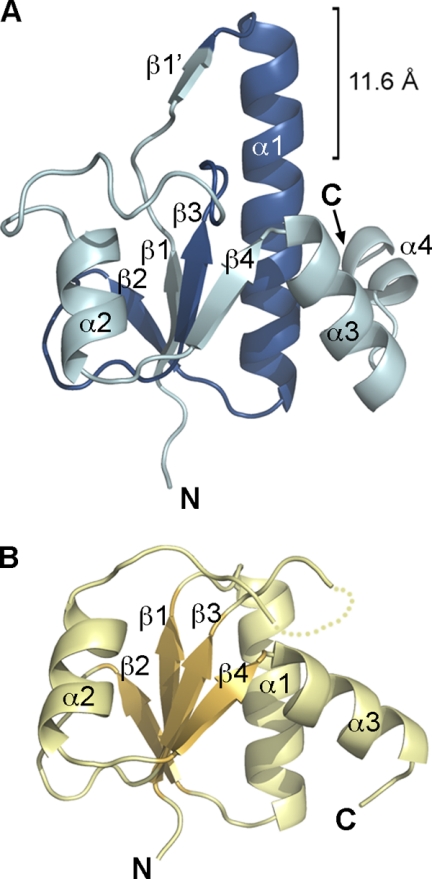

We had previously shown that motif N (residues 135–179) does not constitute an independent folding unit. Conversely, the fragment of Dbf4 encompassing residues 120–250 includes the predicted BRCT domain and is well behaved in solution (24, 29). The structure of this fragment of Dbf4, including a removable hexahistidine tag at the N terminus of the protein, was determined by single anomalous diffraction using selenomethionine-labeled crystals, and 10 molecules were readily identified in the experimental electron density maps. About 20 residues at the C terminus of each monomer (Ala230–Asp250) were disordered and could not be included in the final model. Residues Arg122–Thr224 define a bona fide BRCT domain, consisting of a central four-stranded parallel β-sheet surrounded by α-helices (Figs. 1 and 2).

FIGURE 1.

The fragment of Dbf4 including residues 120–250 folds as a BRCT domain. A, ribbon diagram of the structure of Dbf4 (residues 120–250) colored in blue, with Motif N (residues 135–179) highlighted in a darker shade of blue. The N and C termini, as well as secondary structure elements are labeled. The section of helix α1 protruding from the BRCT core is indicated. B, ribbon diagram of the first BRCT from BRCA-1 (Protein Data Bank entry 1JNX, residues 1649–1737), shown as a pale yellow ribbon and in the same orientation as in A. Secondary structure elements are shown in two shades of yellow and labeled, with the disordered β3-α2 loop depicted as a dotted line.

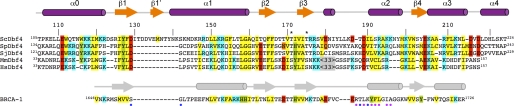

FIGURE 2.

Sequence alignment of the region of Dbf4 that mediates the interaction with Rad53. Structure-based sequence alignment of the H-BRCT domains found in Dbf4 homologues from S. cerevisiae (Sc), Schizosaccharomyces pombe (Sp), Schizosaccharomyces japonicus (Sj), Mus musculus (Mm), and Homo sapiens (Hs) as well as the first BRCT domain found in human BRCA-1 (32). Secondary structure elements of ScDbf4 and BRCA-1 are shown as arrows (strands) and cylinders (helices) and colored as in Fig. 1A. Conserved hydrophobic (yellow), positively charged (blue), and negatively charged (red) residues are highlighted. The positions of the conserved Thr171 and Thr175 are marked with an asterisk. Residues of BRCA1 necessary for the recognition of a Ser(P) residue are marked with a blue dot, and those involved in stabilizing the BRCT repeat are marked with a purple dot.

In comparison with the structures of other BRCT domains determined previously, this domain of Dbf4 has a significantly longer helix α1 that projects an additional β-strand (β1′) out to the solvent (Fig. 1, A and B). This additional strand interacts with the β2-strand of a neighboring molecule, defining a mixed β-sheet with four parallel strands (β4-β3-β1-β2) from one molecule and one anti-parallel (β1′) strand from the adjacent one. As this intermolecular β1′-β2 interaction propagates through the crystal, it defines a right-handed helical filament (supplemental Fig. S1A). Formation of this filament was not due to the presence of the exogenous tag, because this supramolecular organization was also found in crystals grown after removal of the hexahistidine tag (Table 1 and supplemental Fig. S1, B and C). However, size exclusion chromatography and analytical ultracentrifugation experiments indicated that this fragment of Dbf4 exists predominantly as a monomer in solution (supplemental Fig. S1D). Therefore, although the protein-protein interactions seen in the crystals do not reflect the oligomeric state of Dbf4, they could indicate how Dbf4 interacts with other cellular partners.

The BRCT Domain of Dbf4 Is Not Sufficient to Mediate Interaction with Rad53

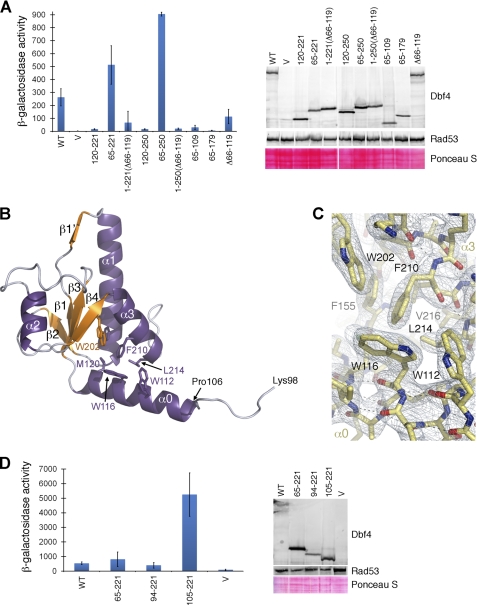

Using yeast two-hybrid analysis, we found that the fragment of Dbf4 encompassing residues 120–221 could not sustain the interaction with Rad53 (Fig. 3A). Because it had been previously shown that a fragment of Dbf4 encompassing residues 1–296 binds Rad53 similarly to wild-type Dbf4 (22), we generated fragments of Dbf4 encompassing additional residues either N- or C-terminal to the BRCT domain. Extending the C-terminal end to include residues 120–250 did not restore the interaction with Rad53. Conversely, extending into the N-terminal region (residues 65–220) did restore this interaction (Fig. 3A). Fragments of Dbf4 starting at residue Leu65 where part or the entire BRCT domain (residues 65–179 or 65–109) was deleted did not support binding to Rad53 either, indicating that the BRCT domain is necessary for the interaction.

FIGURE 3.

The fragment of Dbf4 including residues 105–221 is the minimal domain of Dbf4 that mediates the interaction with Rad53. A, two-hybrid analysis using Rad53 as prey and either full-length Dbf4 (WT), empty vector (V), or regions of Dbf4, as indicated (numbering refers to amino acid positions within full-length Dbf4) as baits. The interaction is shown as β-galactosidase activity units and in each case represents the average of three independent measurements. Error bars, S.D. As a control, whole cell extracts were prepared from transformants following prey induction and analyzed by Western blot using rabbit anti-LexA antibody (Cedarlane Laboratories) to detect bait protein and a mouse monoclonal anti-HA antibody (Sigma) to detect prey protein, along with Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti-rabbit and 488 goat anti-mouse secondary antibodies (Invitrogen), respectively. Prior to detection, the membrane was stained with Ponceau S to assess relative protein loading. B, ribbon diagram of the H-BRCT domain of Dbf4 with α-helices shown in purple, β-strands in orange, and loops in light blue. The N and C termini as well as secondary structure elements are labeled. The additional N-terminal helix is labeled as α0, and the residues defining the hydrophobic core are shown as sticks and labeled. C, detail of the 2Fo − Fc electron density map around Trp116 contoured at 1σ. The H-BRCT model is shown as color-coded sticks with the residues latching the N-terminal helix (α0) to the hydrophobic core of the H-BRCT domain (β4, β1, and α3) labeled. D, two-hybrid analysis using Rad53 as prey and either full-length Dbf4 (WT) or fragments of Dbf4 encompassing residues 65–221, 94–221, and 105–221 as baits. See also supplemental Table S1.

We entertained the possibility that the N-terminal extension (residues 65–119) was merely functioning as a linker between the BRCT domain and the bulky N-terminal LexA tag used in these experiments. Therefore, we generated a fragment of Dbf4 encompassing residues 1–221 but lacking the intervening Gln66–Ile119 region (an internal deletion that changes the sequence connecting LexA to the BRCT domain while maintaining a similar spacing between the two proteins). Notably, this fragment of Dbf4 (1–221Δ66–119) did not support binding to Rad53 (Fig. 3A), indicating that the integrity of the intervening region (residues 66–119) is also necessary for the Dbf4-Rad53 interaction. This demonstrates that both the region encompassing residues Leu65–Ile119 and the intact BRCT domain (Met120–Leu221) are necessary for the Dbf4-Rad53 interaction, whereas neither feature alone can support binding (Fig. 3A). In turn, this suggests that the fragment of Dbf4 encompassing residues Leu65–Leu221 may define a unique structure responsible for mediating the interaction with Rad53.

Structure of Sufficient Domain of Dbf4 for Interaction with Rad53

To elucidate whether this N-terminal extension (residues 65–119) altered the BRCT fold, we determined the crystal structure of the sufficient interaction region of Dbf4 (residues 65–221). Crystals of this fragment diffracted x-rays to 2.6 Å resolution (Table 1) and contained only one molecule in the asymmetric unit, confirming that the filament seen in the previous structures was indeed a crystallographic artifact.

Residues 98–221 were clearly defined in the electron density map; however, the region encompassing residues 65–97 was not. We suspected that this fragment of Dbf4 was susceptible to degradation, and indeed, mass spectrometry confirmed that the crystals contained a fragment of Dbf4 encompassing residues 84–221. As expected, residues 122–221 adopt the BRCT fold seen in the previous structures of Dbf4 (Fig. 1 and supplemental Fig. S1), whereas residues 107–121 form a well defined amphipathic α-helix (α0) that is packed against the hydrophobic surface defined by the C-terminal end of α1, β1, and α3 (Fig. 3B). Despite the low sequence conservation, the presence of a helix N-terminal to the BRCT domain is predicted in most Dbf4 homologues from lower eukaryotes (Fig. 2) (data not shown). The residues upstream of this helix (residues 98–106) adopt an extended and relatively flexible conformation as judged by the quality of the electron density.

To test whether helix α0 was the only relevant feature for binding Rad53 within the region encompassing residues 65–119, we repeated the yeast two-hybrid analysis with shorter fragments of Dbf4. Constructs consisting of residues 94–221 or just 105–221 were capable of binding Rad53 (Fig. 3D; note the difference in scale compared with A). Therefore, we conclude that the region of Dbf4 encompassing residues 105–221 is the minimal structural unit of Dbf4 required for binding to Rad53. Interestingly, the fragment encompassing residues 105–221 interacts with Rad53 more efficiently than Dbf4 itself, suggesting that the full-length protein has additional mechanisms that down-regulate the interaction between the two proteins. This inhibitory effect may arise from other regions of the protein occluding the interaction interface or the competition between Rad53 and other cellular Dbf4-binding proteins. Indeed, it has been shown that Cdc5 interacts with Dbf4 through residues 83–93, and hence, it is conceivable that binding to endogenous Cdc5 restricts binding to Rad53 in our yeast two-hybrid assay (43).

The H-BRCT Fold Is Necessary for Dbf4-Rad53 Interaction

Arguably, helix α0 could be an independent motif adjacent to the BRCT domain whose relative orientation had been determined by crystal packing. However, the side chains of Trp116 and Met120 and, to a lesser extent, Trp112 have extensive van der Waals and aromatic interactions with the hydrophobic core defined by residues Phe155, Trp202, Phe210, and Leu214 (Fig. 3, B and C). Trp116 and Met120 are not strictly conserved in other Dbf4 homologues, but aromatic or bulky hydrophobic residues are found at these positions (Fig. 2), suggesting a common mechanism to occlude the hydrophobic surface defined by Phe155, Trp202, Phe210, and Leu214 and hence supporting the role of this helix in maintaining the structural integrity of the domain. Mutation of Trp116 and Met120 abolishes the interaction between Dbf4 and Rad53 (Fig. 4), indicating that the integrity of the hydrophobic core of the domain is critical for the interaction. These results confirm that the helix N terminus to the BRCT domain is an inherent part of the domain of Dbf4 that we herein refer to as H-BRCT. Recent work has shown that at least another BRCT domain also requires additional structural elements to perform its function (44). However, the H-BRCT domain of Dbf4 constitutes the first example of a BRCT domain where this additional structural motif is an integral part of the folding unit.

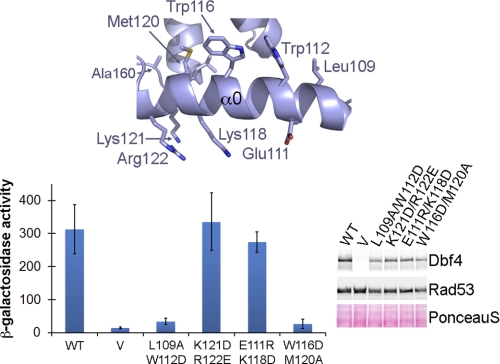

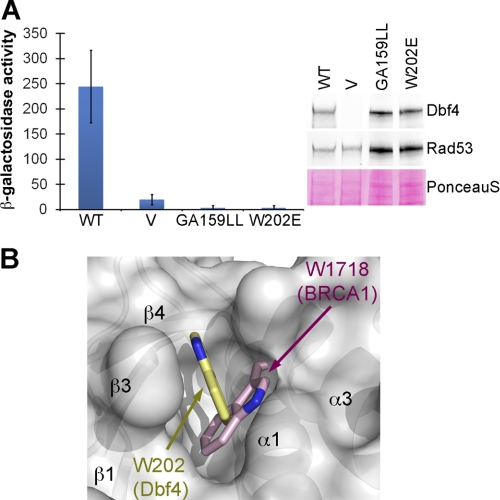

FIGURE 4.

Mutation of the residues anchoring helix α0 to the core of the BRCT domain abolishes the interaction between Dbf4 and Rad53. Two-hybrid analysis carried out using full-length Rad53 as prey and either wild-type Dbf4 (WT), empty vector (V), Dbf4-L109A/W112D (L109A/W112D), Dbf4-K112D/R122E (K112D/R122E), Dbf4-E111R/K118D (E111R/K118D), or Dbf4-W116D/M120A (W116D/M120A) as baits. A detail of helix α0 with the side chains of the residues assayed shown as sticks is shown at the top for reference. Data are presented as in Fig. 3A. See also supplemental Table S1. Error bars, S.D.

Interestingly, the hydrophobic and polar faces of the α0 helix contribute differently to the interaction with Rad53. Mutation of Trp112 and Leu109, which contribute only minimally to the hydrophobic core the H-BRCT domain, also disrupts the Dbf4-Rad53 interaction. Conversely, mutation of the polar face of the helix (K121D/R122E or E111R/K118D) did not affect the interaction (Fig. 4). Collectively, these results indicate that the concave surface defined by α0, β4, and α3 is important for the interaction with Rad53.

Point Mutations That Destabilize H-BRCT Fold Disrupt Dbf4-Rad53 Interaction

Internal deletions disrupting the H-BRCT fold disrupt the interaction with Rad53 (Fig. 3 and supplemental Table S1), demonstrating that the tertiary structure of the H-BRCT domain is important for this function. Therefore, we subsequently investigated whether previously described mutations impairing Dbf4 function could also have folding defects. Three highly conserved residues within the H-BRCT domain (Gly159, Gly/Ala160, and Trp202) are important for Dbf4 function. Mutation of any of these residues causes increased sensitivity to both DNA-damaging agents and hydroxyurea (24) and mutation of the Leu158–Gly159 doublet destroys the interaction between Dbf4 and origin DNA in a yeast one-hybrid assay (21). We found that the Dbf4-W202E and Dbf4-G159L/A160L variants also lost their ability to interact with Rad53 (Fig. 5A and supplemental Table S1). The side chain of Trp-202 lies at the hydrophobic pocket defined by the central β-sheet and the surrounding α0, α1, and α3 helices. Although this residue is not conserved in other BRCT domains, a structurally equivalent tryptophan is found at the N termini of helix α3 in most BRCT domains (Fig. 5B), reinforcing the idea that a hydrophobic, bulky residue at this position is necessary to stabilize the hydrophobic core of the H-BRCT domain. Therefore, the defects associated with mutating Trp-202 are probably due to the structural destabilization of the H-BRCT domain.

FIGURE 5.

Dbf4 mutants that are sensitive to genotoxic agents fail to interact with Rad53. A, two-hybrid analysis was carried out using Rad53 as prey and wild-type Dbf4 (WT), Dbf4-G159L/A160L, or Dbf4-W202E as baits with data presented as in Fig. 3A. B, superimposition of Trp1718 from BRCA-1 (pink color-coded sticks) onto the structure of Dbf4-N. Dbf4-N is shown as a semitransparent white surface with the secondary structure elements shown as a ribbon diagram. Trp202 from Dbf4 is shown as yellow color-coded sticks. See also supplemental Table S1. Error bars, S.D.

The Gly159-Ala160 doublet is located in the short loop connecting α1 and β2 that is conspicuously exposed to solvent. This loop reverses the orientation of the polypeptide chain, and hence, the substitution of these two small and flexible residues by bulky and hydrophobic amino acids probably reduces the plasticity of the α1-β2 loop, potentially destabilizing the central β-sheet (Fig. 1A). Indeed, the φ/ψ angles adopted by Gly159 to make this turn would not be favored for any residue other than glycine, in turn explaining the strict conservation of these two residues among BRCT domains. The H-BRCT-G159L/A160L variant was also insoluble when overexpressed in bacteria using conditions identical to those used to produce the H-BRCT domain (supplemental Fig. S2), reinforcing the idea that these point mutations destabilize the H-BRCT fold. Collectively, these results strongly suggest that the integrity of the H-BRCT domain is critical for the interaction between Dbf4 and Rad53.

Thr-171 Aids Interaction between Dbf4 and Rad53

Mutation of Arg-70 within the FHA1 domain of Rad53, a residue important for the recognition of phosphothreonine (Thr(P)) targets, weakens the interaction with Dbf4, and hence, it had been previously suggested that Rad53 would recognize a phosphoepitope in Dbf4 (22). We confirmed the importance of Arg-70 for this interaction using full-length protein (data not shown). Therefore, we subsequently scanned the sequence of the H-BRCT domains from various Dbf4 homologues to find threonines that could potentially mediate the interaction with Rad53. Only two threonine residues, Thr-171 and Thr-175, are conserved in the H-BRCT domain of Dbf4 (marked with asterisks in Fig. 2). Thr-175 is buried in the hydrophobic core of the H-BRCT domain and is involved in a hydrogen bond network that stabilizes the β3-α2 loop (Fig. 6A). This loop is highly variable among BRCT domains, suggesting that Thr-175 may have a conserved structural role in Dbf4 by stabilizing the β3-α2 loop (supplemental Fig. S3). Due to its location in the domain, we did not expect Thr-175 to be the phosphorylated site recognized by Rad53. Accordingly, mutation of Thr-175 to alanine did not affect the interaction between Dbf4 and Rad53 (supplemental Table S1).

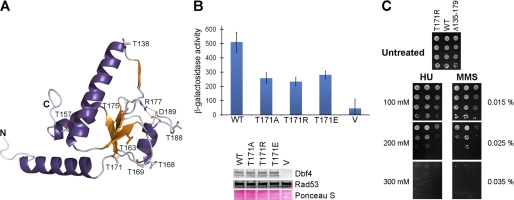

FIGURE 6.

Role of Thr171 and Thr175 in mediating the Dbf4-Rad53 interaction. A, ribbon diagram of the H-BRCT domain colored as in Fig. 3B. The side chains of the threonine residues found in the domain are shown as sticks. The hydrogen bond network restraining the β3-α2 loop is shown as black dashed lines. B, two-hybrid analysis carried out using full-length Rad53 as prey and either full-length Dbf4 or Dbf4 variants carrying point mutations at Thr171 as baits. Data are presented as in Fig. 3A. C, ΔDBF4 cells transformed with CEN vectors (one copy per cell) expressing either wild-type Dbf4 (WT), Dbf4-T171R, or Dbf4 Δ135–179 were spotted in 10-fold dilution series onto SC-Leu (synthetic complete medium, lacking leucine in order to select for plasmid maintenance) plates containing the indicated concentrations of hydroxyurea (HU) or the alkylating agent methyl methanesulfonate (MMS). Each plate was incubated at 30 °C for 3 days. Error bars, S.D.

Conversely, Thr-171 is relatively exposed (Fig. 6A), and the equivalent serine in higher eukaryotes is part of a Chk1 kinase phosphorylation site (45). Mutation of Thr-171 to either alanine or arginine significantly reduced binding to Rad53 (Fig. 6B and supplemental Table S1). Importantly, the Dbf4-T171R variant also showed increased sensitivity to genotoxic agents (Fig. 4B), reinforcing the idea that this residue is important for the Rad53-dependent checkpoint response. However, the H-BRCT-T171A variant was also insoluble when overproduced in bacteria using experimental conditions identical to those used to produce the H-BRCT domain (supplemental Fig. S2), suggesting that this mutation also destabilizes the H-BRCT fold. The side chain of Thr171 is hydrogen-bonded to the main chain of residue Arg125, and this interaction indirectly orients the α0 helix. Therefore, it is not surprising that mutation of Thr171 destabilizes the H-BRCT fold and weakens the interaction between Dbf4 and Rad53.

Should Thr171 be the Thr(P) recognized by Rad53, mutation of Thr171 to a phosphomimetic residue would maintain or even strengthen the interaction between the two proteins. However, the Dbf4-T171E variant also showed reduced binding affinity for Rad53 (Fig. 6B and supplemental Table S1). This result reinforces the idea that Thr171 has a structural role rather than being the phosphoepitope recognized by Rad53. We cannot exclude the possibility that the T171E mutation is not a good mimic for a Thr(P). Indeed, in studies using Thr(P)-containing peptides that recognize FHA1 domains in the absence of any structural context, aspartate cannot efficiently mimic a phosphorylated threonine (26). However, we have demonstrated that the structural integrity of the H-BRCT domain of Dbf4, and hence, the structural context of the putative phosphoepitope must be important. Therefore, we favor the idea that Thr171 also has a structural role, because the double mutation of Thr171 and Thr175 to alanine completely disrupts the interaction between Dbf4 and Rad53 (supplemental Table S1), indicating the synergy between these two destabilizing mutations and restating the importance of the structural integrity of the H-BRCT fold.

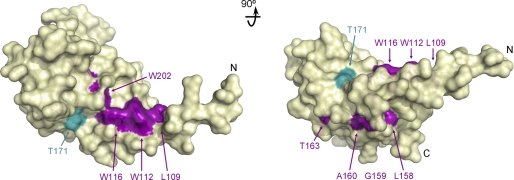

Other Thr residues within this domain of Dbf4 have been proposed as damage-induced phosphorylation sites (11, 19, 46); however, all non-conserved threonine residues within the H-BRCT domain except Thr163 could be replaced without affecting the Dbf4-Rad53 interaction. The Dbf4-T163A variant has reduced affinity for Rad53 (supplemental Table S1). Interestingly, Thr163 resides on the same surface of the H-BRCT domain as Thr171, and it could thus contribute to delineating the interaction interface (Fig. 7).

FIGURE 7.

Surface mapping of the Dbf4 residues important for the interaction with Rad53. Orthogonal views of the H-BRCT domain shown as a yellow ribbon inside a semitransparent surface. Residues that are important for the interaction with Rad53 are colored in purple except for Thr171, which is shown in cyan for clarity.

DISCUSSION

We have shown that the motif N of Dbf4 is part of a unique structure built upon a BRCT domain that includes an additional α-helix strictly required for the function of the domain. We refer to this domain as H-BRCT to signify the location and the nature of the additional structural motif. The H-BRCT domain is necessary and sufficient to mediate the interaction between Dbf4 and Rad53. Interestingly, other proteins containing single BRCT domains also include additional structural elements surrounding the domain that aid their function, suggesting that the BRCT fold is a core whereupon complex structures with different specificities can be built. Tandem BRCT repeats, known to function as a single unit, could be seen as one of the types of structures that can be built upon the BRCT fold. Likewise, single BRCT domains should be considered as part of bigger functional units where the additional BRCT domain found in tandem repeats has been replaced by either a different domain, as in the case of Nbs1 or Chs5 (47–49), or additional structural elements that complement the BRCT fold. Collectively, our results and those from others suggest that other single BRCT domains may also require additional structural motifs, thereby explaining why single BRCT domains do not share a common mechanism of interaction with their binding partners. In turn, this would also explain why BRCT domains, which are commonly found in DNA replication and repair proteins, are not particularly stable and do not show high sequence conservation (32). The most variable regions within the BRCT domain are the loops connecting β2-β3 and β3-α2, which provide the means to gain specificity for different binding partners (supplemental Fig. S3). Here, we propose that additional secondary structural elements at the N or C terminus of the domain can also increase target specificity and present the first example of a BRCT where the additional structural elements have become an integral part of the domain.

BRCT and FHA domains are protein folds with important functions in DNA repair and checkpoint activation. Their mechanisms of Thr(P) recognition have been studied in depth (50–52). However, recent studies have identified novel mechanisms of interaction between FHA and BRCT domains (48, 49). Therefore, the FHA1 domain recognizing a single Thr(P) in the absence of any structural context may no longer be the paradigm that best describes FHA interactions.

Our results reveal that the structural integrity of the H-BRCT fold is more relevant than the presence of a phosphoepitope for the interaction between Dbf4 and Rad53. This finding was somewhat unexpected because it had been proposed that Rad53 would recognize a phosphoepitope in Dbf4 (22). Furthermore, previous structural work had shown that Rad53 recognizes phosphoepitopes in the absence of a structural context (50). However, an elegant study from the Smerdon laboratory has shown that the FHA domain of Mycobacterium tuberculosis Rv1827 recognizes several binding partners in a phosphorylation-independent manner but involving residues integral to the canonical Thr(P)-binding surface (27). Therefore, it is conceivable that the FHA1 domain of Rad53 does not recognize a phosphoepitope in the H-BRCT domain of Dbf4, although mutation of the conserved Arg70 in the FHA1 disrupts the interaction with Dbf4 (22).

The structurally unstable Dbf4Δ135–179, Dbf4-G159L/A160L, Dbf4-W202A, and Dbf4-T171R variants have both a weakened interaction with Rad53 and an increased sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents and hydroxyurea (this work) (24). Interestingly, Gly159, Ala160, Thr163, Thr171, and Trp202 are all in close proximity to helix α0, potentially demarcating the surface of Dbf4 that interacts with Rad53.

The BRCT domain of Dbf4 could be replaced by the BRCT domain found in Rev1 without loss of viability during genotoxic stress, although several other BRCT domains were unable to do so (53). It was suggested that Rev1 and Dbf4 BRCT domains might share a common interaction partner. However, the ability of this Rev1-Dbf4 chimera protein to interact with Rad53 and suppress late origin firing was not examined in that study, and therefore, the need for an intact H-BRCT domain did not become apparent.

Collectively, our work unveils a phosphorylation-independent interaction with the FHA1 domain of Rad53 that relies on the unique H-BRCT domain found at the N terminus of Dbf4. In a broader context, the identification of the H-BRCT domain suggests that other single BRCT domains may also require additional structural motifs for their function. The variable nature of these additional motifs would explain why the mechanisms of interaction of single BRCT domains have remained elusive, whereas those of tandem BRCT domains are well characterized.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yu Seon Chung and staff at the National Synchrotron Light Source for assistance during data collection and Dr. Rodolfo Ghirlando for conducting the analytical ultracentrifugation experiments.

This work was supported by Canadian Institutes of Health Research Grant MOP 67189 (to A. G.) and Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council Grant RGPIN 238392 (to B. P. D.).

This article contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1–S3.

The atomic coordinates and structure factors (codes 3OQ0, 3OQ4, and 3QBZ) have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, Research Collaboratory for Structural Bioinformatics, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, NJ (http://www.rcsb.org/).

- DDK

- Dbf4-dependent kinase

- FHA

- Forkhead-associated

- SeMet

- selenomethionine

- H-BRCT

- Helix-BRCT.

REFERENCES

- 1. Bruck I., Kaplan D. (2009) Dbf4-Cdc7 phosphorylation of Mcm2 is required for cell growth. J. Biol. Chem. 284, 28823–28831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ferreira M. F., Santocanale C., Drury L. S., Diffley J. F. (2000) Dbf4p, an essential S phase-promoting factor, is targeted for degradation by the anaphase-promoting complex. Mol. Cell Biol. 20, 242–248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weinreich M., Stillman B. (1999) Cdc7p-Dbf4p kinase binds to chromatin during S phase and is regulated by both the APC and the RAD53 checkpoint pathway. EMBO J. 18, 5334–5346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheng L., Collyer T., Hardy C. F. (1999) Cell cycle regulation of DNA replication initiator factor Dbf4p. Mol. Cell Biol. 19, 4270–4278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jackson A. L., Pahl P. M., Harrison K., Rosamond J., Sclafani R. A. (1993) Cell cycle regulation of the yeast Cdc7 protein kinase by association with the Dbf4 protein. Mol. Cell Biol. 13, 2899–2908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Marston A. L. (2009) Meiosis. DDK is not just for replication. Curr. Biol. 19, R74–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matos J., Lipp J. J., Bogdanova A., Guillot S., Okaz E., Junqueira M., Shevchenko A., Zachariae W. (2008) Dbf4-dependent CDC7 kinase links DNA replication to the segregation of homologous chromosomes in meiosis I. Cell 135, 662–678 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Patterson M., Sclafani R. A., Fangman W. L., Rosamond J. (1986) Molecular characterization of cell cycle gene CDC7 from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 1590–1598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Miller C. T., Gabrielse C., Chen Y. C., Weinreich M. (2009) Cdc7p-Dbf4p regulates mitotic exit by inhibiting Polo kinase. PLoS Genet. 5, e1000498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Pessoa-Brandão L., Sclafani R. A. (2004) CDC7/DBF4 functions in the translesion synthesis branch of the RAD6 epistasis group in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 167, 1597–1610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Zegerman P., Diffley J. F. (2010) Checkpoint-dependent inhibition of DNA replication initiation by Sld3 and Dbf4 phosphorylation. Nature 467, 474–478 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Shirahige K., Hori Y., Shiraishi K., Yamashita M., Takahashi K., Obuse C., Tsurimoto T., Yoshikawa H. (1998) Regulation of DNA-replication origins during cell cycle progression. Nature 395, 618–621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Lopes M., Cotta-Ramusino C., Pellicioli A., Liberi G., Plevani P., Muzi-Falconi M., Newlon C. S., Foiani M. (2001) The DNA replication checkpoint response stabilizes stalled replication forks. Nature 412, 557–561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Santocanale C., Diffley J. F. (1998) A Mec1- and Rad53-dependent checkpoint controls late-firing origins of DNA replication. Nature 395, 615–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Lucca C., Vanoli F., Cotta-Ramusino C., Pellicioli A., Liberi G., Haber J., Foiani M. (2004) Checkpoint-mediated control of replisome-fork association and signaling in response to replication pausing. Oncogene 23, 1206–1213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Pellicioli A., Lucca C., Liberi G., Marini F., Lopes M., Plevani P., Romano A., Di Fiore P. P., Foiani M. (1999) Activation of Rad53 kinase in response to DNA damage and its effect in modulating phosphorylation of the lagging strand DNA polymerase. EMBO J. 18, 6561–6572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pellicioli A., Foiani M. (2005) Signal transduction. How rad53 kinase is activated. Curr. Biol. 15, R769–R771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kihara M., Nakai W., Asano S., Suzuki A., Kitada K., Kawasaki Y., Johnston L. H., Sugino A. (2000) Characterization of the yeast Cdc7p/Dbf4p complex purified from insect cells. Its protein kinase activity is regulated by Rad53p. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 35051–35062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lopez-Mosqueda J., Maas N. L., Jonsson Z. O., Defazio-Eli L. G., Wohlschlegel J., Toczyski D. P. (2010) Damage-induced phosphorylation of Sld3 is important to block late origin firing. Nature 467, 479–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Masai H., Arai K. (2000) Dbf4 motifs. Conserved motifs in activation subunits for Cdc7 kinases essential for S-phase. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 275, 228–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ogino K., Takeda T., Matsui E., Iiyama H., Taniyama C., Arai K., Masai H. (2001) Bipartite binding of a kinase activator activates Cdc7-related kinase essential for S phase. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31376–31387 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Duncker B. P., Shimada K., Tsai-Pflugfelder M., Pasero P., Gasser S. M. (2002) An N-terminal domain of Dbf4p mediates interaction with both origin recognition complex (ORC) and Rad53p and can deregulate late origin firing. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 16087–16092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Varrin A. E., Prasad A. A., Scholz R. P., Ramer M. D., Duncker B. P. (2005) A mutation in Dbf4 motif M impairs interactions with DNA replication factors and confers increased resistance to genotoxic agents. Mol. Cell Biol. 25, 7494–7504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gabrielse C., Miller C. T., McConnell K. H., DeWard A., Fox C. A., Weinreich M. (2006) A Dbf4p BRCA1 C-terminal-like domain required for the response to replication fork arrest in budding yeast. Genetics 173, 541–555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Heffernan T. P., Unsal-Kaçmaz K., Heinloth A. N., Simpson D. A., Paules R. S., Sancar A., Cordeiro-Stone M., Kaufmann W. K. (2007) Cdc7-Dbf4 and the human S checkpoint response to UVC. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 9458–9468 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Durocher D., Henckel J., Fersht A. R., Jackson S. P. (1999) The FHA domain is a modular phosphopeptide recognition motif. Mol. Cell 4, 387–394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Nott T. J., Kelly G., Stach L., Li J., Westcott S., Patel D., Hunt D. M., Howell S., Buxton R. S., O'Hare H. M., Smerdon S. J. (2009) An intramolecular switch regulates phosphoindependent FHA domain interactions in Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Sci. Signal 2, ra12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Pike B. L., Yongkiettrakul S., Tsai M. D., Heierhorst J. (2004) Mdt1, a novel Rad53 FHA1 domain-interacting protein, modulates DNA damage tolerance and G2/M cell cycle progression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Biol. 24, 2779–2788 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Matthews L. A., Duong A., Prasad A. A., Duncker B. P., Guarné A. (2009) Crystallization and preliminary X-ray diffraction analysis of motif N from Saccharomyces cerevisiae Dbf4. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. F Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun. 65, 890–894 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Leung C. C., Glover J. N. (2011) BRCT domains. Easy as one, two, three. Cell Cycle 10, 2461–2470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mohammad D. H., Yaffe M. B. (2009) 14-3-3 proteins, FHA domains, and BRCT domains in the DNA damage response. DNA repair 8, 1009–1017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Williams R. S., Green R., Glover J. N. (2001) Crystal structure of the BRCT repeat region from the breast cancer-associated protein BRCA1. Nat. Struct. Biol. 8, 838–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hendrickson W. A., Horton J. R., LeMaster D. M. (1990) Selenomethionyl proteins produced for analysis by multiwavelength anomalous diffraction (MAD). A vehicle for direct determination of three-dimensional structure. EMBO J. 9, 1665–1672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Otwinowski Z., Minor W. (1997) Processing of x-ray diffraction data collected in oscillation mode. Methods Enzymol. 276, 307–326 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Adams P. D., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Hung L. W., Ioerger T. R., McCoy A. J., Moriarty N. W., Read R. J., Sacchettini J. C., Sauter N. K., Terwilliger T. C. (2002) PHENIX. Building new software for automated crystallographic structure determination. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 58, 1948–1954 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Emsley P., Cowtan K. (2004) Coot. Model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 60, 2126–2132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. McCoy A. J., Grosse-Kunstleve R. W., Adams P. D., Winn M. D., Storoni L. C., Read R. J. (2007) Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl. Crystallogr. 40, 658–674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. DeLano W. L. (2002) The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Schrodinger, LLC, New York [Google Scholar]

- 39. Jones D. R., Prasad A. A., Chan P. K., Duncker B. P. (2010) The Dbf4 motif C zinc finger promotes DNA replication and mediates resistance to genotoxic stress. Cell Cycle 9, 2018–2026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Dohrmann P. R., Oshiro G., Tecklenburg M., Sclafani R. A. (1999) RAD53 regulates DBF4 independently of checkpoint function in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genetics 151, 965–977 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Ausubel F., Brent R., Kingston R. E., Moore D. D., Seidman J. G., Smith J. A., Struhl K. (1995) in Short Protocols in Molecular Biology, 3rd Ed., Wiley, New York [Google Scholar]

- 42. Cormack B., Castaño I. (2002) Introduction of point mutations into cloned genes. Methods Enzymol. 350, 199–218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Chen Y. C., Weinreich M. (2010) Dbf4 regulates the Cdc5 Polo-like kinase through a distinct non-canonical binding interaction. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41244–41254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Kobayashi M., Ab E., Bonvin A. M., Siegal G. (2010) Structure of the DNA-bound BRCA1 C-terminal region from human replication factor C p140 and model of the protein-DNA complex. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 10087–10097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Kim J. M., Yamada M., Masai H. (2003) Functions of mammalian Cdc7 kinase in initiation/monitoring of DNA replication and development. Mutat. Res. 532, 29–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Duch A., Palou G., Jonsson Z. O., Palou R., Calvo E., Wohlschlegel J., Quintana D. G. (2011) A Dbf4 mutant contributes to bypassing the Rad53-mediated block of origins of replication in response to genotoxic stress. J. Biol. Chem. 286, 2486–2491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Martín-García R., de León N., Sharifmoghadam M. R., Curto M. Á., Hoya M., Bustos-Sanmamed P., Valdivieso M. H. (2011) The FN3 and BRCT motifs in the exomer component Chs5p define a conserved module that is necessary and sufficient for its function. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 68, 2907–2917 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Lloyd J., Chapman J. R., Clapperton J. A., Haire L. F., Hartsuiker E., Li J., Carr A. M., Jackson S. P., Smerdon S. J. (2009) A supramodular FHA/BRCT-repeat architecture mediates Nbs1 adaptor function in response to DNA damage. Cell 139, 100–111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Williams R. S., Dodson G. E., Limbo O., Yamada Y., Williams J. S., Guenther G., Classen S., Glover J. N., Iwasaki H., Russell P., Tainer J. A. (2009) Nbs1 flexibly tethers Ctp1 and Mre11-Rad50 to coordinate DNA double-strand break processing and repair. Cell 139, 87–99 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Durocher D., Taylor I. A., Sarbassova D., Haire L. F., Westcott S. L., Jackson S. P., Smerdon S. J., Yaffe M. B. (2000) The molecular basis of FHA domain:phosphopeptide binding specificity and implications for phospho-dependent signaling mechanisms. Mol. Cell 6, 1169–1182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Glover J. N., Williams R. S., Lee M. S. (2004) Interactions between BRCT repeats and phosphoproteins. Tangled up in two. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 579–585 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Campbell S. J., Edwards R. A., Glover J. N. (2010) Comparison of the structures and peptide binding specificities of the BRCT domains of MDC1 and BRCA1. Structure 18, 167–176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Harkins V., Gabrielse C., Haste L., Weinreich M. (2009) Budding yeast Dbf4 sequences required for Cdc7 kinase activation and identification of a functional relationship between the Dbf4 and Rev1 BRCT domains. Genetics 183, 1269–1282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.