Background: Protein folding in cells is intimately coupled to protein synthesis.

Results: GFP and RFP folding involves slow, cell autonomous insertion of the last β-strand into a stable cotranslational folding intermediate.

Conclusion: Fluorescent β-barrel proteins utilize kinetically coupled co- and post-translational folding strategies.

Significance: Specialized folding properties of GFP and RFP facilitate fluorescence acquisition in diverse biological environments.

Keywords: Fluorescence; Kinetics; Protein Folding; Protein Self-assembly; Protein Synthesis; Ribosomes; Green Fluorescent Protein, GFP; Red Fluorescent Protein. RFP; Cotranslational Protein Folding; In Vitro Translation

Abstract

Protein folding in cells reflects a delicate interplay between biophysical properties of the nascent polypeptide, the vectorial nature and rate of translation, molecular crowding, and cellular biosynthetic machinery. To better understand how this complex environment affects de novo folding pathways as they occur in the cell, we expressed β-barrel fluorescent proteins derived from GFP and RFP in an in vitro system that allows direct analysis of cotranslational folding intermediates. Quantitative analysis of ribosome-bound eCFP and mCherry fusion proteins revealed that productive folding exhibits a sharp threshold as the length of polypeptide from the C terminus to the ribosome peptidyltransferase center is increased. Fluorescence spectroscopy, urea denaturation, and limited protease digestion confirmed that sequestration of only 10–15 C-terminal residues within the ribosome exit tunnel effectively prevents stable barrel formation, whereas folding occurs unimpeded when the C terminus is extended beyond the ribosome exit site. Nascent FPs with 10 of the 11 β-strands outside the ribosome exit tunnel acquire a non-native conformation that is remarkably stable in diverse environments. Upon ribosome release, these structural intermediates fold efficiently with kinetics that are unaffected by the cytosolic crowding or cellular chaperones. Our results indicate that during synthesis, fluorescent protein folding is initiated cotranslationally via rapid formation of a highly stable, on-pathway structural intermediate and that the rate-limiting step of folding involves autonomous incorporation of the 11th β-strand into the mature barrel structure.

Introduction

Protein folding is often characterized in terms of a spontaneous funnel or landscape that proceeds energetically downhill from a randomly oriented polypeptide to a relatively compact native conformation (1, 2). Although such models provide useful tools to describe protein folding in dilute solution, they often fail to take into account key properties of biological systems such as the vectorial nature of synthesis, rate of peptide elongation, restriction within the ribosome exit tunnel, cytosolic crowding, and interactions with translation and cellular folding machinery (3–7). For example, denatured small globular proteins such as lysozyme can theoretically acquire secondary and/or tertiary structures in vitro on a submillisecond to millisecond time scale (8). Yet in eukaryotic cells protein synthesis takes seconds to minutes as amino acids are added at a rate of 5–7/s. This imposes an enormous disparity between the theoretical kinetic limits of folding and the time taken to actually fold in vivo. In addition, protein synthesis takes place at the peptidyltransferase center and proceeds vectorially from N to C terminus as the nascent chain elongates within a narrow tunnel in the large ribosome subunit (9). Nascent chains exit the ribosome into cytosol where chaperone and co-chaperone binding minimizes off-pathway intermediates by providing a more favorable folding environment (Hsp60/TRiC/CCT), transiently sequestering aggregation prone peptide regions (Hsc70, Hsp40), and/or facilitating native packing of globular core domains (Hsp90) (10–13). The physiological environment in the cell therefore has a major influence on conformational diversity, and hence the cotranslational folding pathway of the growing nascent chain.

One approach to characterize de novo folding in the context of native biosynthetic machinery has been to use in vitro translation systems to generate ribosome-attached nascent chains that resemble biosynthetic intermediates captured at a specific stage of synthesis (14–16). In such a system, conformational status can be assessed by functional properties (17–20), limited proteolysis (21, 22), conformation specific antibodies (23, 24), fluorescence resonance energy transfer (25, 26), and recently, NMR spectroscopy (27, 28). Although relatively few substrates have been examined to date, findings indicate that folding in the cell can increase kinetics and improve folding efficiency when compared with in vitro refolding studies (17, 18, 20, 21). Cotranslational folding may also may involve remodeling of misfolded or scrambled states rather than the sequential folding of repeat domains (29). Interestingly, cotranslational folding may proceed via unique intermediates not detected during in vitro folding that minimize off-pathway aggregation (24). This latter finding may be particularly important for proteins rich in β-structure, where achieving a highly stable native state benefits from a smoother in vivo folding energy landscape (30). To determine whether these principles are broadly applicable, particularly for simple, single domain proteins, it is important to examine proteins with specific folding requirements.

Fluorescent proteins (FPs)2 derived from green (GFP) and red (RFP) fluorescent protein represent a well studied family with a defined functional end point. FPs contain 11 β-strands arranged in a barrel structure with α-helical caps and a central axial helix with 3 adjacent residues that form the active chromophore (31). This conserved structure has also been referred to as a β-can (31), although here we use the more common nomenclature of β-barrel. Because barrel formation is essential for chromophore cyclization and oxidation (32, 33), fluorescence provides a sensitive and precise means to monitor acquisition of native structure. Covalent modifications of the chromophore, however, induce a rough energy landscape that is characterized by a pronounced hysteresis in in vitro re-folding studies (34–36). Thus de novo FP folding prior to chromophore formation differs from refolding of denatured (mature) protein (37). The FP barrel also exhibits a high absolute contact order that reflects a preponderance of nonlocal interactions (38) and suggests that barrel folding involves cooperative, rather than sequential (i.e. N-to-C terminus) positioning of β-strands. Although, cotranslational FP folding is more efficient than in vitro refolding (20), the nature of cotranslational folding intermediates and the impact of cellular biosynthetic machinery on kinetics and efficiency of β-barrel formation remain poorly understood.

In the present study, we investigate the folding of ribosome-attached nascent FPs that are synthesized in vitro from truncated RNA transcripts. By controlling the amount of C-terminal polypeptide that resides within the ribosome exit tunnel, we show that sequestration of even a few C-terminal residues kinetically traps the FP at a remarkably stable, non-native, on-pathway folding intermediate. Synchronous release of these nascent chains from the ribosome mimics the process of translation termination and allowed us to measure real-time kinetics for de novo β-barrel folding. Our results demonstrate that in cells, FP folding is a multistep process in which cotranslational formation of a ribosome-bound intermediate is followed by the rate-limiting incorporation of the (11th) β-strand into the β-barrel structure after ribosome release. Moreover, the kinetics and efficiency of this rate-limiting step are unaffected by cytosolic crowding and/or chaperone machinery, consistent with a highly autonomous process.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Plasmid Construction

FP fusion proteins were generated by ligating coding sequences for eCFP (pECFP.Cl; Clontech), eGFP (pEGFP N3 (39)), Citrine (pCDNA3-YC 3.3 (40)), Venus (pJPA5-ER-Venus), mCherry (pJPA5-Cherry (41)), and mStrawberry (pRSET-B mStrawberry (41)) to the 5′ end of the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) cDNA in pSP-CFTR (42) with a 6-amino acid linker (VRPRET) between the last residue of the FP sequence and Met-1 of the CFTR. Sequences were amplified by PCR, digested with AvaI, and ligated with a similarly digested pSP-CFTR vector. For pSP-Citrine and pSP-mStrawberry, the PCR fragment was digested with Xho and BstE2 and ligated into similarly digested pSP-CFTR vector. TAG codons were engineered into parent plasmids using PCR overlap extension. Sequence of PCR amplified DNA was verified by sequencing (mCherry, mTangerine, and mStrawberry coding sequences were generously provided by Roger Tsien).

In Vitro Transcription and Translation

cDNA was amplified by PCR (Vent DNA Polymerase, New England Biolabs, Beverly, MA) using a 5′-oligonucleotide complementary to pSP64 BP(2757) (TAGAGGATCTGGCTAGCGAT) and a 3′-oligonucleotide complementary to the CFTR coding sequence. For each truncation, the last codon was converted to valine to minimize spontaneous hydrolysis of the peptidyl-tRNA bond. In vitro transcription was carried out (43) using SP6 polymerase at 40 °C for 1 h and added directly (20% volume) to a rabbit reticulocyte lysate (RRL) in vitro translation reaction supplemented with [35S]methionine and a synthetic suppressor aminoacyl-tRNA, [14C]Lys-tRNAamb (0.8 μm) (25, 44, 45). Translation was carried out at 24 °C for 1 h as described previously (25). For fluorescence spectroscopy, [35S]methionine was omitted and the translation reaction was supplemented with 40 μm methionine. For experiments involving urea denaturation, translation efficiency was increased by using transcription conditions from Pokrovskaya and Gurevich (46), and translation was carried out as described with the following exceptions: 0.6 μg of transcript was added per 10-μl reaction, 40 mm Tris acetate was replaced by 20 mm Hepes-KOH, added MgoAc was reduced from 2 to 1.6 mm, and supplemental amino acids were added to a final concentration of 50 μm.

Ribosome Nascent Chain Complex (RNC) Purification and Fluorescence Spectroscopy

For SDS-PAGE analysis, RNCs were collected by pelleting for 1 h at 350,000 × g. Pellets were resuspended in 1% SDS and 100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, and analyzed on 12–17% gels by phosphorimaging (Personal FX PhosphorImager and QuantityOne software (Bio-Rad)). For fluorescence spectroscopy, 250-μl translation reactions were subjected to gel filtration at 4 °C on Sepharose CL-6B (Sigma) in 20 mm Hepes-KOH, pH 7.6, 100 mm KoAC, 14 mm MgoAc. Ribosomes eluting in the void volume were used for fluorescence spectroscopy based on A260. Steady state fluorescence spectroscopy was performed in 4 × 4-mm quartz cuvettes using a Jobin Yvon-Horiba FluoroLog 3–22 spectrofluorometer (Edison, NJ) at 24 °C, unless otherwise stated. Background signal was determined from similarly prepared RNCs lacking fluorescent protein. As indicated, RNase A was added (0.1. mg/ml) directly to the cuvette. Fluorescence intensity was calculated based on [14C]Lys incorporation assuming that each nascent chain that reads through the engineered UAG stop codon contains a single [14C]Lys residue. 14C counts (cpm) were measured at the end of each experiment by scintillation counting (30 min) in a LS 6500 Scintillation system (Beckman, Fullerton, CA) and converted to picomole of FP/μl according to: [FP] = cpm/(CE)(SA)(vol), where CE is the counting efficiency of the scintillation counter (0.85 cpm/dpm), SA is the calculated specific activity (dpm/pmol) of [14C]Lys, and vol is the sample volume counted (μl).

FP Maturation Kinetics

For time course measurements, purified RNCs were transferred to cuvettes at 24 °C, released from ribosomes by addition of 0.1 mg/ml of RNase A, and fluorescence spectra were recorded at the times shown (λex = 430 nm (eCFP), 480 nm (eGFP), 515 nm (Venus), and 583 nm (mCherry)). Rate constants were determined from plots of background-corrected peak fluorescence intensity using Prism 4 (GraphPad Software Inc., San Diego CA) according to the equation: F = Fo + (Fmax − Fo)(1 − e−kt), where F is the background subtracted peak fluorescence intensity at time t, Fmax is the maximal fluorescence intensity, Fo is the initial fluorescence intensity measured at t = 0, and k is a first-order rate constant. Because the data suggested a sequential process involving multiple rate constants, the initial lag phase, which reflects barrel folding, was evaluated separately (see below).

De Novo Folding Kinetics

Gel purified RNCs were incubated in RNase A, and aliquots were brought to 4 m urea at the times indicated. Samples were incubated at 24 °C for a total time of 430 min, and fluorescence emission spectra were recorded (λex = 583 nm). Background-corrected fluorescence intensity (λem = 605 nm) at each time point was expressed as a percent of maximal fluorescence obtained upon addition of urea. Curves were fitted as above to calculate rate constants. Representative data are shown, the t½ values are averages of at least two independent experiments. To compare the effect of cytosol on FP folding kinetics, translation was carried out at 24 °C for 25 min. RNCs were either isolated directly or further incubated in RRL in the presence of 20 μg/ml of cyclohexamide. Folding in buffer was measured as described above, whereas folding in RRL was determined by isolating RNCs at the times indicated and immediately adding 4 m urea. Fluorescence was measured at t = 430 min (λex = 583 nm, λem = 605 nm). Background-corrected fluorescence is expressed as a percent of maximal fluorescence obtained upon addition of urea at t = 430 min.

Limited Proteolysis

Translation products in RRL were incubated in trypsin at the indicated concentrations for 10 min at 4 °C, and trypsin was then inactivated by rapid addition of phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (10 mm) and transfer to 10 volumes of 1% SDS, 100 mm Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, preheated to 100 °C. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE (12–17% gels) and phosphorimaging. Band intensities were calculated based on background-corrected volume-averaged pixel intensity. Data show averages of at least three independent experiments ± S.E. For Fig. 8C, RNCs were collected by pelleting for 1 h at 350,000 × g and resuspended in 20 mm Hepes-KOH, pH 7.6, 100 mm KoAC, 14 mm MgoAc prior to trypsin digestion.

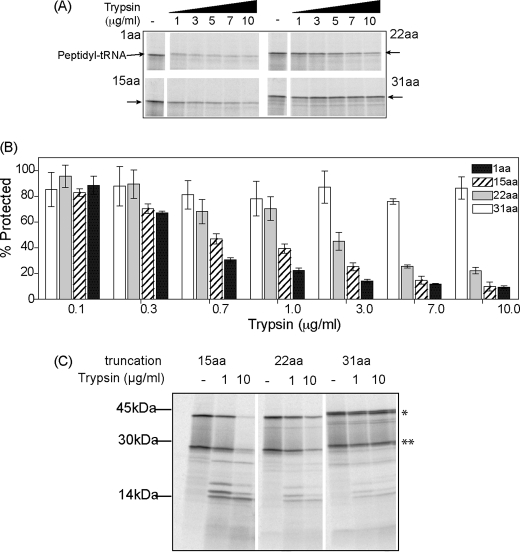

FIGURE 8.

Conformational sensitivity of kinetically trapped folding intermediates. A, [35S]Met-labeled mCherry translation products were subjected to limited trypsin digestion in RRL. Protease-resistant peptidyl-tRNA bands (arrows) with tether lengths of 1, 15, 22, and 31 aa are shown. B, quantification of trypsin-resistant fragments as shown on panel A was determined by phosphorimaging and expressed as % of the peptidyl-tRNA band present prior to digestion. Data show average of at least three independent experiments ± S.E. C, RNCs were isolated by pelleting and subjected to trypsin digestion as in panel A. In this case, all bands are derived from peptidyl-tRNA, some of which were hydrolyzed during SDS-PAGE and give rise to proteolytic fragments most prominent for nascent chains containing a 15-aa tether.

RESULTS

Experimental Strategy

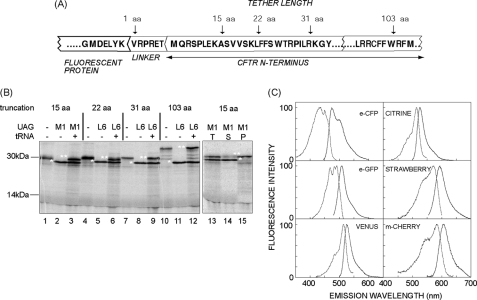

The kinetic disparity between secondary structure formation and the rate of translation suggests that cotranslational folding intermediates are formed during synthesis as the nascent chain emerges from the ribosome exit tunnel (17). A common way to evaluate such intermediates is to translate truncated RNA transcripts lacking a terminal stop codon in a reconstituted, in vitro translation system (25, 45, 47). Upon reaching the last available codon, the nascent chain therefore remains tethered to the ribosome via a covalent peptidyl-tRNA bond. These arrested RNCs provide a snapshot of cotranslational intermediates and allow one to study how proteins fold vectorially as they emerge from the ribosome (25, 26, 28, 48). To generate ribosome-bound FP intermediates, we fused GFP (eCFP, eGFP, Venus, and Citrine) and RFP (mStrawberry, mCherry, DS Red, and mTangerine) variants to a C-terminal reporter protein (CFTR). RNA transcripts were truncated downstream of the last FP codon and translated in RRL to capture different lengths of the FP C terminus within the ribosome exit tunnel (Fig. 1A). To facilitate nascent chain quantitation, a single [14C]lysine residue was incorporated at an amber stop codon in the reporter domain (M1UAG or L6UAG) using a modified amber suppressor tRNA, [14C]Lys-tRNAamb (25). When translated in RRL, nascent chains either terminate at the stop codon and are released from the ribosome (Fig. 1B, lanes 2, 5, 8, and 11) or readthrough the stop codon to the end of the transcript and are isolated as intact RNCs (Fig. 1B, lanes 13–15). In contrast to in vivo expression where nascent chains of different lengths were isolated on polysomes (20), our in vitro system contains excess transcripts, which typically results in single 5′ translation initiation event (Fig. 1B)

FIGURE 1.

In vitro generation and fluorescence of FP RNCs. A, diagram of the FP fusion protein showing the C terminus of the FP, 6-aa linker, and N-terminal residues of CFTR. Truncations sites (arrows) are indicated. B, autoradiogram of 35S-labeled eCFP-CFTR translation products (left panel) with and without UAG codon expressed in the presence or absence of [14C]Lys-tRNAamb (tRNA). Truncation sites are indicated at the top. Polypeptides that terminate or readthrough the UAG codon are indicated by single and double asterisks, respectively. In the right panel, RNCs from the translation (T) were pelleted into the supernatant (S) and pellet (P) fractions. Polypeptides that terminate at UAG (*) are released from the ribosome, whereas readthrough products (**) remain ribosome bound. C, fluorescence excitation and emission spectra obtained from purified FP-RNC complexes containing a 103 C-terminal tether. Spectra were corrected for background (mock translation) and measured >4 h at 24 °C post-purification and arbitrarily normalized to 100.

To determine whether FPs translated in RRL could fold while still attached to the ribosome, transcripts were truncated 103 residues downstream of the FP, and RNCs were isolated by gel filtration and subjected to fluorescence spectroscopy. After subtracting background signal derived from parallel mock translation reactions (see “Experimental Procedures”), six of eight FPs tested yielded characteristic excitation and emission spectra (Fig. 1C). Two RFP variants, dsRed and Tangerine, were undetectable (data not shown). When corrected for nascent chain concentration, the fluorescence intensity at each corresponding λmax yielded a profile of Venus > eGFP > eCFP > mCherry > mStrawberry in good agreement with previous reports (41). Moreover, at least 80% of protein (mCherry) expressed in RRL was correctly folded based on the normalized fluorescence emission obtained from recombinant protein isolated from Escherichia coli (not shown).

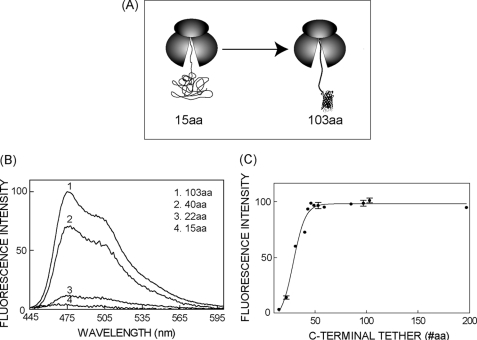

Nascent FP Fluorescence Is Constrained by C Terminus Sequestration in the Ribosome Tunnel

We next truncated the eCFP fusion protein at increasing distances beyond its C terminus to determine the minimal C-terminal tether length that allowed native FP folding in the ribosome-attached state. Fluorescence emission spectra, corrected for nascent chain concentration, revealed undetectable fluorescence at a tether length of 15 aa, whereas emission spectra were readily obtained at truncations of 40 and 103 (Fig. 2B). A more detailed analysis revealed a sharp threshold for eCFP folding as the C-terminal tether was increased from 15 to 45 aa, which is consistent with the length of polypeptide required to span the 100-Å ribosome exit tunnel (Fig. 2C). A similar pattern was obtained for mCherry although fluorescence plateaued at a slightly shorter tether length (data not shown). These results indicate that barrel formation is restricted until C-terminal residues exit from the ribosome and that FP folding can occur in close proximity to the ribosome exit tunnel.

FIGURE 2.

Nascent FP maturation is constrained by the ribosome exit tunnel. A, diagram of RNCs truncated 15 and 103 aa C-terminal to CFP showing possible conformational states of ribosome attached nascent chains. B, eCFP fluorescence emission spectra obtained from isolated RNCs containing C-terminal tethers of indicated lengths. Spectral intensity was corrected for background signal, and normalized for nascent chain concentration as determined by [14C]Lys incorporation. C, background-corrected peak fluorescence intensity of eCFP-RNCs normalized to chain concentration and plotted as a function of C-terminal tether length. All fluorescence measurements were taken at 4 °C. Where present, error bars represent S.E., n ≥ 3.

De Novo Folding of Kinetically Trapped Intermediates

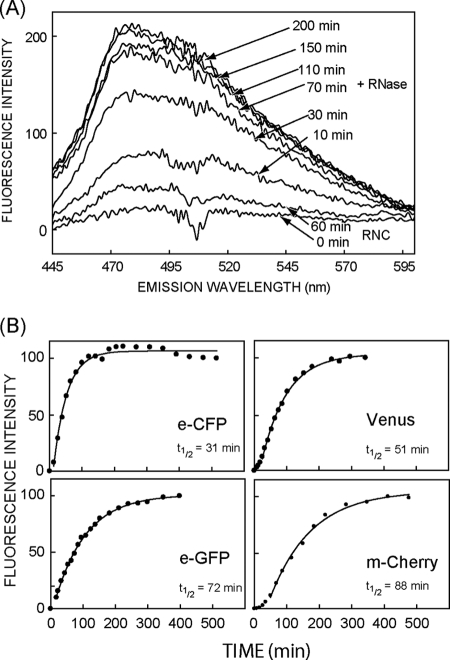

Results in Fig. 2 indicate that full-length eCFP, like GFP (20), can be held in a nonfluorescent state when its last remaining C-terminal residues are sequestered by the ribosome. To test whether these ribosome-bound polypeptides reflect an on-pathway folding intermediate, isolated RNCs were incubated with RNase, which rapidly releases the nascent chain by cleaving the peptidyl-tRNA bond (∼10 s, data not shown), thereby mimicking translation termination. As shown in Fig. 3A, eCFP with a 15-aa tether remained nonfluorescent for 60 min, while attached to the ribosome but acquired fluorescence following RNase digestion. Thus the nascent chain is kinetically trapped in a folding-competent state when C-terminal residues are sequestered within the exit tunnel. Following ribosome release, eCFP, eGFP, Venus, and mCherry each isolated as RNCs with a 15-aa tether, exhibited an initial lag phase (most prominent for Venus and mCherry) followed by a rise in fluorescence that followed first-order kinetics with a calculated t½ of 31, 72, 51, and 88 min, respectively (Fig. 3B). If barrel folding occurs during the lag phase, then these rate constants reflect kinetics of subsequent chromophore maturation inside the folded barrel. The t½ obtained for eGFP (72 min) compares well with the value of 84 min reported for S65T-GFP renatured from inclusion bodies (35). eCFP and Venus are variants of eGFP developed for brighter, wavelength-shifted emission and faster chromophore maturation (49), and both exhibit a shorter t½ compared with eGFP. The longer t½ for mCherry (88 min) likely reflects additional steps required for formation of the RFP chromophore (50–52).

FIGURE 3.

De novo FP maturation kinetics following ribosome release. A, eCFP fluorescence emission spectra of isolated RNCs (15 aa tether) prior to (RNC) and after ribosome release by RNase digestion (+RNase). Spectra were measured at 24 °C at the times indicated. B, time-dependent increase in peak fluorescence intensity of eCFP, eGFP, Venus, and mCherry following ribosome release (15 aa tether) at t = 0. Fluorescence at each time point was determined after background correction and normalization to the maximum intensity was obtained. Data were fitted to single exponential kinetics after ignoring the initial “lag” phase. Representative data sets are shown, whereas t½ is the average of at least two independent measurements.

Tether Length Affects FP Maturation Kinetics

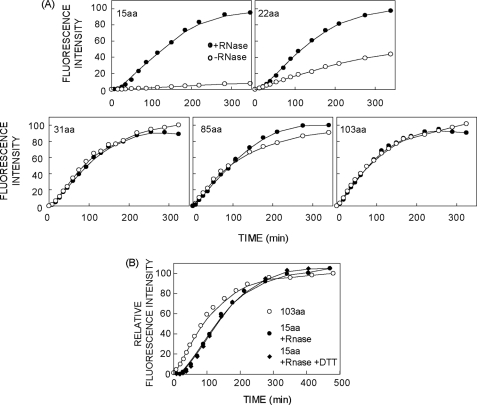

To further understand how the ribosome affects cotranslational folding, the mCherry fusion protein was truncated 15, 22, 31, 85, or 103 aa beyond its C terminus, and maturation kinetics were determined in both ribosome-attached and released states (Fig. 4A). With a 15-aa tether, maturation was completely blocked in intact RNCs even after prolonged (>5 h) incubation. At tether lengths of 31 aa and longer, the ribosome had no effect on chromophore maturation, whereas the tether length of 22 aa resulted in a slow increase in fluorescence. These truncations therefore represent three distinct conditions for cotranslational folding. The 15-aa tether is too short for folding to be completed. The 22-aa tether allows folding to occur, but at a much reduced rate, possibly as a result of steric constraints imposed either by close proximity to the ribosome vestibule or dynamic flexibility of the tether in the exit tunnel. At tether lengths ≥31 aa, the rate of nascent chain folding is unaffected by attachment to the ribosome. Interestingly, initial fluorescence of isolated RNCs was undetectable (at t = 0) regardless of tether length due to the slow maturation of the mCherry chromophore (see Fig. 3B), However, the delay in fluorescence (lag phase) was no longer apparent at tether lengths ≥31 aa, which suggests that some barrel folding takes place during synthesis and/or RNC isolation (discussed below, see Figs. 6B and 7E). Control experiments showed that for all truncations, at least 90% of nascent chains remained ribosome-bound for the duration of the experiment, confirming that acquisition of fluorescence in the absence of RNase was not due to spontaneous hydrolysis of the peptidyl-tRNA bond (not shown). Quantification of fluorescence per nascent chain synthesized also revealed that maturation efficiency in the ribosome-attached state is virtually identical regardless of whether the entire mCherry sequence exits the ribosome cotranslationally (103 aa tether) or is kinetically trapped on the ribosome and released post-translationally (15 aa tether, Fig. 4B). Thus, post-translational release of ribosome-trapped nascent chains efficiently reconstitutes de novo FP folding.

FIGURE 4.

C-terminal tether length constrains mCherry chromophore maturation. A, peak corrected mCherry fluorescence emission intensity was measured at 24 °C at the times indicated using intact RNCs (open circles) and after release of the nascent chain with RNase (filled circles). C-terminal tether length is indicated in each panel. Data were obtained simultaneously for parallel translation samples in each panel. Peak fluorescence intensities were corrected for [14C]Lys content and normalized to the maximum value obtained in each experiment. Spline lines are shown merely as guides to the eye. B, maturation time course of mCherry RNCs measured on intact RNCs containing a 103-aa tether or following ribosome release with RNase with a 15-aa tether in the presence or absence of 0.1 mm DTT. In all experiments, fluorescence intensity was corrected for nascent chain concentration based on [14C]Lys incorporation. Spectra were taken at 24 °C.

FIGURE 6.

De novo folding kinetics of the mCherry β-barrel following ribosome release. A, experimental design used to measure FP folding kinetics as described in Fig. 5. B, β-barrel folding curves based on the acquisition of resistance to 4 m urea. Plot was fitted to single exponential kinetics as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Representative data are shown in B and t½ values in C are averages of at least two independent experiments.

FIGURE 7.

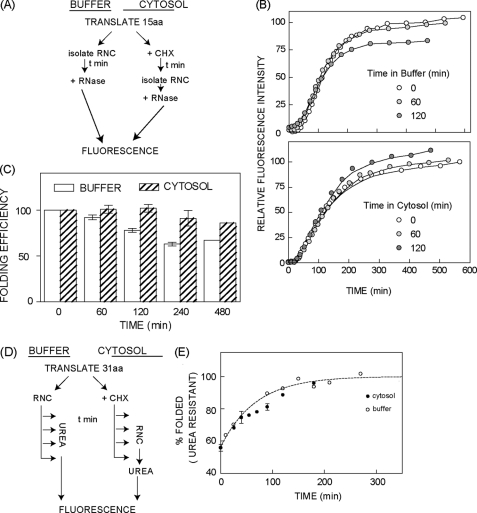

Cytosolic crowding and chaperone machinery do not affect kinetics or stability of nascent mCherry folding intermediates. A, experimental design to measure stability of the nascent mCherry polypeptide. B, maturation time course of mCherry (15 aa tether) following ribosome release after incubation of intact RNCs in buffer (top panel) or RRL translation reaction (bottom panel). Time points refer to the length of incubation prior to ribosome release (buffer) or RNC purification from RRL (cytosol) followed by ribosome release. Background-subtracted peak fluorescence intensity was corrected for [14C]Lys incorporation and normalized to the maximal fluorescence obtained without incubation. C, quantification of folding efficiency determined from experiments in panel B shown normalized to the value obtained at t = 0 incubation time. Data show average of three experiments ± S.E. or 2 experiments (480 min). D, experimental design to measure cytosol effects on folding kinetics. E, folding kinetics of ribosome bound mCherry (31 aa tether) in buffer (open circles) and RRL translation reaction (filled circles). x-Axis refers either to the time of urea addition after RNC isolation in buffer or the duration of RNC incubation in RRL prior to RNC isolation. In each case, fluorescence was measured after maximal chromophore maturation had occurred as described in the legend to Fig. 5. Data shows average of at least two independent experiments and where indicated error bars represent S.E., n ≥ 3.

C-terminal Sequestration in Ribosome Kinetically Traps Nascent FPs in a Non-native Conformation

FP fluorescence is acquired as the result of several distinct kinetic steps that include β-barrel folding as well as cyclization, oxidation, and dehydration of the chromogenic tripeptide. Because the chromophore can only form within the shielded confines of a fully formed β-barrel, folding must be completed before chromophore modification can occur. To tease out these early folding events, we took advantage of the observation that once folded, the GFP β-barrel is relatively resistant to urea denaturation, whereas urea prevents folding of GFP molecules that have not reached their native state (35). In addition, chromophore maturation can proceed unimpeded inside a pre-folded barrel even in the presence of urea (35, 53). The fraction of folded FPs in a population of nascent polypeptides can therefore be determined by monitoring fluorescence acquisition in the presence of urea, because only the prefolded β-barrels will give rise to a mature chromophore.

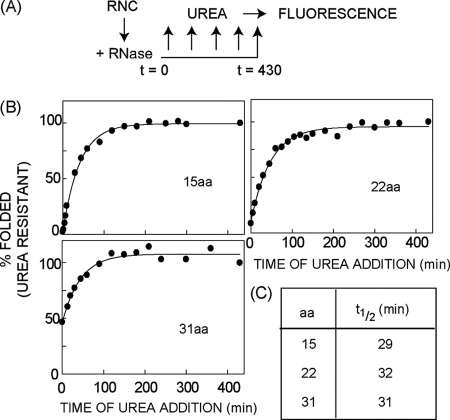

Consistent with these findings, chromophore maturation was blocked when RNCs containing immature mCherry (with 15 or 22 aa C-terminal tethers) were incubated in 6 m urea immediately after RNase release (Fig. 5A). Similar results were obtained for 4 m but not 2 m urea (Fig. 5B). We therefore added 4 m urea at specific time points after ribosome release to prevent further barrel folding, whereas at the same time allowing chromophore maturation to proceed in those polypeptides that had achieved a native fold. Fig. 5C shows the time-dependent increase in fluorescence intensity, which, after correcting for the small quenching effect of urea, reflects the fraction of polypeptides that were fully folded at the time of urea addition. These results confirm that mCherry RNCs are kinetically trapped in a non-native conformation and that the urea-resistant conformation is achieved only after the C terminus exits from the ribosome.

FIGURE 5.

Nascent mCherry is sensitive to urea denaturation prior to folding. A, time course of mCherry chromophore maturation in the presence (open circles) or absence (filled circles) of 6 m urea following RNase release of nascent chains (15 and 22 aa tethers). B, mCherry maturation is inhibited in the presence of 4 and 6 m but not 2 m urea. C, mCherry nascent chains (22 aa tether) were released from the ribosome at t = 0 and 4 m urea was added at t = 0, 20, 60, or 430 min. Peak fluorescence intensity at each time point following ribosome release was corrected for nascent chain concentration and normalized to the fluorescence intensity obtained at the last time point in the absence of urea.

The strategy shown in Fig. 5 further allowed us to determine the kinetics of de novo β-barrel folding by incubating mCherry in 4 m urea at sequential times after ribosome release (Fig. 6A). For C-terminal tether lengths of 15 and 22 aa, β-barrel folding was effectively prevented even though the entire protein is synthesized and ∼95% of the polypeptide resides outside the ribosome (t = 0, Fig. 6B). In contrast, nearly 50% of chains with a 31-aa tether acquired urea resistance during the translation reaction and/or RNC isolation. Despite these differences, nascent chains exhibited first-order kinetics for β-barrel formation with a t½ of ∼30 min regardless of the initial tether length (Fig. 6C). This implies that nascent chains follow similar folding pathways for each truncation and that the rate-limiting step of FP folding takes place only after the last (11th) β-strand has fully emerged from the ribosome (see below).

Nascent FP Stability and Folding Kinetics Are Unaffected by Cytosolic Environment

Based on the above results we conclude that the 15-aa tether provides an efficient kinetic trap that retains nascent FPs in a non-native conformation solely due to the inaccessibilty of C-terminal residues. We therefore examined whether this folding intermediate might be susceptible to irreversible off-pathway folding events, and if so, whether the crowded cytosolic environment might influence its ability to retain a folding-competent conformation. For these experiments mCherry RNCs (15 aa tether) were either isolated and incubated in buffer, or translation was halted by addition of cyclohexamide and RNCs were further incubated in the RRL translation reaction (∼80–100 mg/ml of protein) (Fig. 7A). In both conditions, nascent chains retained folding competence for more than 8 h, 67%, and 86%, respectively (Fig. 7, B and C). Moreover, nascent chains exhibited indistinguishable folding kinetics following ribosome release regardless of their preincubation conditions. Thus ribosome-attached nascent FPs maintain a remarkably stable folding-competent conformation.

With a 31-aa tether mCherry folding is unaffected by the ribosome (Fig. 4), and ∼50% of nascent polypeptides have not fully folded at the time of RNC purification (Fig. 6B). To determine whether cytosol might affect folding kinetics, these RNCs were either purified and folded in dilute buffer with urea added at specified time points, or nascent mCherry was allowed to fold in RRL (+ cyclohexamide) for specified times followed by RNC isolation and urea addition (Fig. 7D). In both cases maximal fluorescence was measured after a total time of 430 min as in Fig. 5. Because RRL provides a chaperone-rich environment, we anticipated that the FP yield might be improved at the expense of slower folding kinetics. Surprisingly, however, folding kinetics were very similar under both conditions (Fig. 7E).

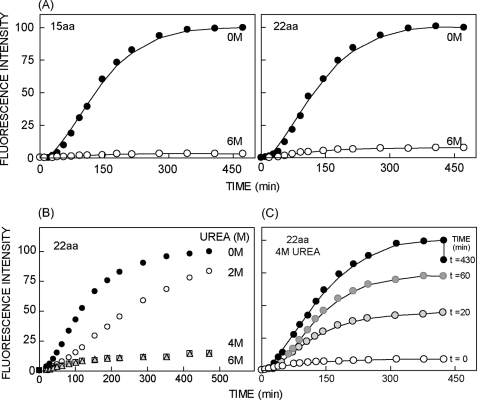

C-terminal Tether Length Influences Conformation of Kinetically Trapped Folding Intermediates

Last, we tested whether tether length might influence the structure of ribosome-bound folding intermediates. In this respect, FPs are relatively protease-sensitive prior to folding, whereas the compact nature of the barrel confers resistance to proteolytic digestion (35, 54, 55). mCherry RNCs with C-terminal tethers of 1, 15, 22, and 31 aa were all resistant to digestion at the lowest concentration (0.1 μg/ml), whereas only polypeptides containing the 31-aa tether remained resistant at 10 μg/ml (Fig. 8, A and B). Interestingly, at tether lengths of 1 or 15 aa, cleavage was observed at concentrations of 0.3–1.0 μg/ml, whereas polypeptides with a 22-aa tether were preferentially digested at concentrations greater than 1.0 μg/ml (Fig. 8B). Thus, even though 15- and 22-aa truncations both prevent FP folding as determined by urea sensitivity, the increase in tether length of 7 aa results in a slightly more protease-resistant conformation. Following RNC purification, nascent chains with a 15-aa tether also yielded distinct proteolytic fragments (∼14 to 30 kDa in size), which were less prominent in the 22-aa truncation and nearly undetectable in the 31-aa truncation (Fig. 8C). The lower susceptibility to proteolytic digestion observed for the 22-aa truncation correlates with its ability to undergo slow chromophore maturation (Fig. 4). Because mCherry contains 32 potential trypsin cleavage sites, the appearance of distinct cleavage fragments suggests that even the 15-aa tether allows shielding of some target sites, whereas leaving others accessible.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, much effort has been invested in understanding folding mechanisms and chromophore chemistry of naturally occurring fluorescent proteins GFP, RFP, and their derivatives (56). These proteins exhibit two distinct maturation phases, formation of a stable, 11-stranded β-barrel structure, followed by alignment, cyclization, and oxidation of a tripeptide chromophore within the shielded central cavity of the barrel. Despite successful reconstitution of FP folding and unfolding in vitro, however, relatively little has been discovered about how these proteins acquire their unique barrel structure under native conditions as they are synthesized in the cell. To address this issue we have defined several key parameters of FP folding prior to and following cotranslational release of the nascent chain from the ribosome. Importantly, by analyzing ribosome-bound nascent chains with defined C-terminal tether lengths, we not only eliminate the impact of preformed chromophore present in many in vitro refolding studies, but also recapitulate vectorial aspects of folding imposed by cellular translation machinery.

Our results show that formation of the characteristic FP β-barrel is prevented by sequestration of only a few C-terminal residues within the ribosome exit tunnel. In contrast, folding proceeds unimpeded when the last C terminus residue has extended at least 31 aa beyond the ribosome peptidyl transferase center. Thus, the ribosome constrains tertiary folding as expected (3, 57), but has no detectable influence on either kinetics or yield once the C terminus has exited from the tunnel. Remarkably, cotranslational folding intermediates with 10 β-strands outside the exit tunnel remain kinetically trapped in a non-native, on-pathway intermediate structure that retains folding competence for prolonged periods of time. We also show that the final step in FP folding is relatively unaffected by the cellular folding environment. Finally, kinetic analysis revealed that cotranslational FP folding involves at least two steps: formation of a partially folded intermediate, and slow incorporation of the 11th β-strand (and possibly others) into the final barrel structure.

In eukaryotic cells, nascent chains move sequentially during synthesis through the RNA-rich and solvent-accessible ribosome exit tunnel prior to entering the cytosol (9, 58, 59). Although the narrow diameter of the exit tunnel (10–20 Å) allows, and may actually stimulate secondary structure formation (26, 60–64), its dimensions preclude tertiary folding of most globular domains (9). Because most fluorescent proteins contain 10–11 residues after the last β strand that are not required for folding (51, 65), extending the C terminus by 15 aa would provide a maximal tether length of 88 Å (3.4 Å/aa), thus constraining the 11th β-strand within the 100-Å long tunnel. The remaining 10 β-strands outside the ribosome give rise to an intermediate that lacks the characteristic stability of the fully folded barrel and does not support chromophore formation. These findings are consistent with split FP constructs that also fail to form a chromophore in vitro when the 11th strand is deleted (66). In contrast, the 22-aa tether (plus 11 aa C terminus) would minimally span the ribosome tunnel if fully extended. This would position the 11th strand within or adjacent to the ribosome exit vestibule, whose wider dimensions and potentially dynamic nature allows formation of certain tertiary interactions (57, 67). The slow maturation kinetics observed at the 22-aa truncation (Fig. 4) could therefore be explained by either the close proximity of the nascent protein to the ribosome (electrostatic or steric effects), or limited availability of the 11th strand in the tunnel vestibule due to a degree of secondary structure within the tether that reduces its effective length.

The efficiency of folding, stability of the ribosome-bound state, folding kinetics, and proteolytic digestion patterns observed here provide evidence that FPs with 15 or 22 aa tethers cotranslationally acquire an intermediate structure that likely involves at least some of the available β-strands. These findings are consistent with partially folded FP structures observed during in vitro refolding of fast folding/maturing GFP variants (68) where an on-pathway “molten globule” intermediate (69, 70) was mapped to β strands 1 and 3 (34), and in another study, a stable core containing β strands 1, 2, 4, 5, and 6 (71). Single molecule mechanical unfolding experiments have also identified a stable N-terminal core intermediate comprising strands 1–6 (72), and rewired (circularly permuted) GFPs require that β strands 1–6 be expressed contiguously for chromophore formation (73). A core N-terminal region containing the first 6 β-strands is also consistent with the size of the protease-resistant fragments shown in Fig. 8. Given that β-strands 1–10 can partially shield a pre-formed chromophore from solvent (74, 75) even though they do not allow de novo chromophore formation, it is also possible that these nascent chains adopt a more complex intermediate structure involving additional available strands.

By separating β-barrel folding from chromophore maturation using a urea trapping strategy (35), we demonstrated that mCherry folds with a t½ of ∼30 min after the nascent chain exits the ribosome. Interestingly, nascent chains that remained trapped on the ribosome for varying times (15 and 22 aa tethers) exhibit indistinguishable folding kinetics upon release compared with nascent chains that fold continuously (31 aa tether) (Figs. 6 and 7E). Because FP synthesis in mammalian cells is predicted to take approximately 1 min (at 5–7 aa/s), cotranslational folding (of strands 1–10) therefore does not contribute significantly to the overall folding rate, and the rate-limiting step must occur only after the nascent chain is released from the ribosome. Interestingly this last step is unaffected by cytosol, suggesting that cellular chaperones are not required for the final stage of mCherry folding. One implication of these findings is that the improved yield previously reported for GFP in vivo as opposed to in vitro (20) may involve formation of the early cotranslational folding intermediate, rather than the last step when the 11th strand becomes available.

In summary, we propose that cotranslational folding of the β-barrel protein mCherry occurs through a landscape characterized by rapid formation of a stable N-terminal folding intermediate that likely occurs coincident with, and may be facilitated by vectorial elongation of the nascent chain. These events are followed by a slow, rate-limiting step after ribosome release that requires the 11th β-strand to form the final barrel structure necessary for chromophore catalysis. In cells, these events would normally be coupled when synthesis is completed and the nascent chain is released from the ribosome. An interesting question is whether the rate-limiting step of barrel formation reflects partial unfolding of an intermediate, or is simply limited by the ability of the 11th strand to intercalate into a core scaffold structure. It is also important to consider that despite their conserved architecture, folding rates for FPs are faster for genetically selected “super folder” proteins. Future studies using such substrates as well as circularly permuted FPs that vary the identity of the last synthesized strand will likely provide important clues as to the precise nature of the rate-limiting step and/or cotranslational folding intermediates.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Volodomir Zeeneko and Karl Rusterholtz for technical help and Dr. Elisa Cooper for early characterization of FP CFTR fusion proteins, and Roger Tsien for generously providing mTangerine, mStrawberry, and mCherry cDNAs. We also thank members of the Skach Laboratory for useful discussions.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants GM53456 and DK51818 and Cystic Fibrosis Foundation Therapeutics Grant SKACH05X0.

- FP

- fluorescent protein

- aa

- amino acid

- eCFP

- enhanced cyan fluorescent protein

- eGFP

- enhanced green fluorescent protein

- RFP

- red fluorescent protein

- RNC

- ribosome nascent chain complex

- RRL

- rabbit reticulocyte lysate

- CFTR

- cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator.

REFERENCES

- 1. Leopold P. E., Montal M., Onuchic J. N. (1992) Protein folding funnels. A kinetic approach to the sequence-structure relationship. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 89, 8721–8725 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Ozkan S. B., Dill K. A., Bahar I. (2002) Fast-folding protein kinetics, hidden intermediates, and the sequential stabilization model. Protein Sci. 11, 1958–1970 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Clark P. L. (2004) Protein folding in the cell. Reshaping the folding funnel. Trends Biochem. Sci. 29, 527–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hartl F. U., Hayer-Hartl M. (2009) Converging concepts of protein folding in vitro and in vivo. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 574–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Kramer G., Boehringer D., Ban N., Bukau B. (2009) The ribosome as a platform for cotranslational processing, folding and targeting of newly synthesized proteins. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 589–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Mankin A. S. (2006) Nascent peptide in the “birth canal” of the ribosome. Trends Biochem. Sci. 31, 11–13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fulle S., Gohlke H. (2009) Statics of the ribosomal exit tunnel. Implications for cotranslational peptide folding, elongation regulation, and antibiotics binding. J. Mol. Biol. 387, 502–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Matagne A., Dobson C. M. (1998) The folding process of hen lysozyme. A perspective from the “new view.” Cell Mol. Life Sci. 54, 363–371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Voss N. R., Gerstein M., Steitz T. A., Moore P. B. (2006) The geometry of the ribosomal polypeptide exit tunnel. J. Mol. Biol. 360, 893–906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Thulasiraman V., Yang C. F., Frydman J. (1999) In vivo newly translated polypeptides are sequestered in a protected folding environment. EMBO J. 18, 85–95 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Etchells S. A., Meyer A. S., Yam A. Y., Roobol A., Miao Y., Shao Y., Carden M. J., Skach W. R., Frydman J., Johnson A. E. (2005) The cotranslational contacts between ribosome-bound nascent polypeptides and the subunits of the hetero-oligomeric chaperonin TRiC probed by photocross-linking. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 28118–28126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hoffmann A., Merz F., Rutkowska A., Zachmann-Brand B., Deuerling E., Bukau B. (2006) Trigger factor forms a protective shield for nascent polypeptides at the ribosome. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 6539–6545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Krukenberg K. A., Street T. O., Lavery L. A., Agard D. A. (2011) Conformational dynamics of the molecular chaperone Hsp90. Q. Rev. Biophys. 44, 229–255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Evans M. S., Ugrinov K. G., Frese M. A., Clark P. L. (2005) Homogeneous stalled ribosome nascent chain complexes produced in vivo or in vitro. Nat. Methods 2, 757–762 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schaffitzel C., Ban N. (2007) Generation of ribosome nascent chain complexes for structural and functional studies. J. Struct. Biol. 158, 463–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Johnson A. E. (2005) The cotranslational folding and interactions of nascent protein chains. A new approach using fluorescence resonance energy transfer. FEBS Lett. 579, 916–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Fedorov A. N., Baldwin T. O. (1995) Contribution of cotranslational folding to the rate of formation of native protein structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 92, 1227–1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Nicola A. V., Chen W., Helenius A. (1999) Cotranslational folding of an alphavirus capsid protein in the cytosol of living cells. Nat. Cell Biol. 1, 341–345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Svetlov M. S., Kommer A., Kolb V. A., Spirin A. S. (2006) Effective cotranslational folding of firefly luciferase without chaperones of the Hsp70 family. Protein Sci. 15, 242–247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ugrinov K. G., Clark P. L. (2010) Cotranslational folding increases GFP folding yield. Biophys. J. 98, 1312–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Maggioni M. C., Liscaljet I. M., Braakman I. (2005) A critical step in the folding of influenza virus HA determined with a novel folding assay. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 258–263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kleizen B., van Vlijmen T., de Jonge H. R., Braakman I. (2005) Folding of CFTR is predominantly cotranslational. Mol. Cell 20, 277–287 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Clark P. L., King J. (2001) A newly synthesized, ribosome-bound polypeptide chain adopts conformations dissimilar from early in vitro refolding intermediates. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 25411–25420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Evans M. S., Sander I. M., Clark P. L. (2008) Cotranslational folding promotes beta-helix formation and avoids aggregation in vivo. J. Mol. Biol. 383, 683–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Khushoo A., Yang Z., Johnson A. E., Skach W. R. (2011) Ligand-driven vectorial folding of ribosome-bound human CFTR NBD1. Mol. Cell 41, 682–692 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Woolhead C. A., McCormick P. J., Johnson A. E. (2004) Nascent membrane and secretory proteins differ in FRET-detected folding far inside the ribosome and in their exposure to ribosomal proteins. Cell 116, 725–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Eichmann C., Preissler S., Riek R., Deuerling E. (2010) Cotranslational structure acquisition of nascent polypeptides monitored by NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 9111–9116 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Cabrita L. D., Hsu S. T., Launay H., Dobson C. M., Christodoulou J. (2009) Probing ribosome-nascent chain complexes produced in vivo by NMR spectroscopy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 22239–22244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Jansens A., van Duijn E., Braakman I. (2002) Coordinated nonvectorial folding in a newly synthesized multidomain protein. Science 298, 2401–2403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Xia K., Manning M., Hesham H., Lin Q., Bystroff C., Colón W. (2007) Identifying the subproteome of kinetically stable proteins via diagonal two-dimensional SDS/PAGE. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 17329–17334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Yang F., Moss L. G., Phillips G. N., Jr. (1996) The molecular structure of green fluorescent protein. Nat. Biotechnol. 14, 1246–1251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ormö M., Cubitt A. B., Kallio K., Gross L. A., Tsien R. Y., Remington S. J. (1996) Crystal structure of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein. Science 273, 1392–1395 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Yarbrough D., Wachter R. M., Kallio K., Matz M. V., Remington S. J. (2001) Refined crystal structure of DsRed. A red fluorescent protein from coral, at 2.0-A resolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 462–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Huang J. R., Craggs T. D., Christodoulou J., Jackson S. E. (2007) Stable intermediate states and high energy barriers in the unfolding of GFP. J. Mol. Biol. 370, 356–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Reid B. G., Flynn G. C. (1997) Chromophore formation in green fluorescent protein. Biochemistry 36, 6786–6791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Andrews B. T., Schoenfish A. R., Roy M., Waldo G., Jennings P. A. (2007) The rough energy landscape of superfolder GFP is linked to the chromophore. J. Mol. Biol. 373, 476–490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Andrews B. T., Roy M., Jennings P. A. (2009) Chromophore packing leads to hysteresis in GFP. J. Mol. Biol. 392, 218–227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Kamagata K., Arai M., Kuwajima K. (2004) Unification of the folding mechanisms of non-two-state and two-state proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 339, 951–965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Cormack B. P., Valdivia R. H., Falkow S. (1996) FACS-optimized mutants of the green fluorescent protein (GFP). Gene 173, 33–38 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Griesbeck O., Baird G. S., Campbell R. E., Zacharias D. A., Tsien R. Y. (2001) Reducing the environmental sensitivity of yellow fluorescent protein. Mechanism and applications. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29188–29194 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Shaner N. C., Steinbach P. A., Tsien R. Y. (2005) A guide to choosing fluorescent proteins. Nat. Methods 2, 905–909 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Hasegawa H., Skach W., Baker O., Calayag M. C., Lingappa V., Verkman A. S. (1992) A multifunctional aqueous channel formed by CFTR. Science 258, 1477–1479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Oberdorf J., Skach W. R. (2002) In vitro reconstitution of CFTR biogenesis and degradation. Methods Mol. Med. 70, 295–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. McCormick P. J., Miao Y., Shao Y., Lin J., Johnson A. E. (2003) Cotranslational protein integration into the ER membrane is mediated by the binding of nascent chains to translocon proteins. Mol. Cell 12, 329–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Sadlish H., Pitonzo D., Johnson A. E., Skach W. R. (2005) Sequential triage of transmembrane segments by Sec61α during biogenesis of a native multispanning membrane protein. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 870–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pokrovskaya I. D., Gurevich V. V. (1994) In vitro transcription. Preparative RNA yields in analytical scale reactions. Anal. Biochem. 220, 420–423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Devaraneni P. K., Conti B., Matsumura Y., Yang Z., Johnson A. E., Skach W. R. (2011) Stepwise insertion and inversion of a type II signal anchor sequence in the ribosome-Sec61 translocon complex. Cell 146, 134–147 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Kowarik M., Küng S., Martoglio B., Helenius A. (2002) Protein folding during cotranslational translocation in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Mol. Cell 10, 769–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Miyawaki A., Llopis J., Heim R., McCaffery J. M., Adams J. A., Ikura M., Tsien R. Y. (1997) Fluorescent indicators for Ca2+ based on green fluorescent proteins and calmodulin. Nature 388, 882–887 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Verkhusha V. V., Chudakov D. M., Gurskaya N. G., Lukyanov S., Lukyanov K. A. (2004) Common pathway for the red chromophore formation in fluorescent proteins and chromoproteins. Chem. Biol. 11, 845–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shu X., Shaner N. C., Yarbrough C. A., Tsien R. Y., Remington S. J. (2006) Novel chromophores and buried charges control color in mFruits. Biochemistry 45, 9639–9647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Remington S. J. (2006) Fluorescent proteins, maturation, photochemistry, and photophysics. Curr. Opin. Struct. Biol. 16, 714–721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Ward W. W., Prentice H. J., Roth A. F., Cody C. W., Reeves S. C. (1982) Spectral perturbation of the Aqueorea green fluorescent protein. Photochem. Photobiol. 35, 803–808 [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tsien R. Y. (1998) The green fluorescent protein. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 509–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Sniegowski J. A., Phail M. E., Wachter R. M. (2005) Maturation efficiency, trypsin sensitivity, and optical properties of Arg-96, Glu-222, and Gly-67 variants of green fluorescent protein. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 332, 657–663 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Hsu S. T., Blaser G., Jackson S. E. (2009) The folding, stability, and conformational dynamics of β-barrel fluorescent proteins. Chem. Soc. Rev. 38, 2951–2965 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kosolapov A., Deutsch C. (2009) Tertiary interactions within the ribosomal exit tunnel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 16, 405–411 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Picking W. D., Picking W. L., Odom O. W., Hardesty B. (1992) Fluorescence characterization of the environment encountered by nascent polyalanine and polyserine as they exit Escherichia coli ribosomes during translation. Biochemistry 31, 2368–2375 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Ban N., Nissen P., Hansen J., Moore P. B., Steitz T. A. (2000) The complete atomic structure of the large ribosomal subunit at 2.4-Å resolution. Science 289, 905–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lu J., Deutsch C. (2005) Folding zones inside the ribosomal exit tunnel. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 1123–1129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Gajewski C., Dagcan A., Roux B., Deutsch C. (2011) Biogenesis of the pore architecture of a voltage-gated potassium channel. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 3240–3245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Daniel C. J., Conti B., Johnson A. E., Skach W. R. (2008) Control of translocation through the Sec61 translocon by nascent polypeptide structure within the ribosome. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 20864–20873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Ziv G., Haran G., Thirumalai D. (2005) Ribosome exit tunnel can entropically stabilize α-helices. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 18956–18961 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. O'Brien E. P., Stan G., Thirumalai D., Brooks B. R. (2008) Factors governing helix formation in peptides confined to carbon nanotubes. Nano Lett. 8, 3702–3708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Li X., Zhang G., Ngo N., Zhao X., Kain S. R., Huang C. C. (1997) Deletions of the Aequorea victoria green fluorescent protein define the minimal domain required for fluorescence. J. Biol. Chem. 272, 28545–28549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Cabantous S., Waldo G. S. (2006) In vivo and in vitro protein solubility assays using split GFP. Nat. Methods 3, 845–854 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. O'Brien E. P., Hsu S. T., Christodoulou J., Vendruscolo M., Dobson C. M. (2010) Transient tertiary structure formation within the ribosome exit port. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 132, 16928–16937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Hsu S. T., Behrens C., Cabrita L. D., Dobson C. M. (2009) 1H, 15N, and 13C assignments of yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) Venus. Biomol. NMR Assign 3, 67–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Fukuda H., Arai M., Kuwajima K. (2000) Folding of green fluorescent protein and the cycle 3 mutant. Biochemistry 39, 12025–12032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Enoki S., Saeki K., Maki K., Kuwajima K. (2004) Acid denaturation and refolding of green fluorescent protein. Biochemistry 43, 14238–14248 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Huang J. R., Hsu S. T., Christodoulou J., Jackson S. E. (2008) The extremely slow-exchanging core and acid-denatured state of green fluorescent protein. HFSP J. 2, 378–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Bertz M., Kunfermann A., Rief M. (2008) Navigating the folding energy landscape of green fluorescent protein. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 47, 8192–8195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Reeder P. J., Huang Y. M., Dordick J. S., Bystroff C. (2010) A rewired green fluorescent protein. Folding and function in a nonsequential, noncircular GFP permutant. Biochemistry 49, 10773–10779 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Kent K. P., Boxer S. G. (2011) Light-activated reassembly of split green fluorescent protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 4046–4052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Kent K. P., Childs W., Boxer S. G. (2008) Deconstructing green fluorescent protein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 130, 9664–9665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]